1. Overview

Marguerite Higgins Hall (September 3, 1920 - January 3, 1966) was an American reporter and pioneering war correspondent whose career spanned World War II, the Korean War, and the Vietnam War. She dedicated most of her career to the New York Herald Tribune from 1942 to 1963, and later became a syndicated columnist for Newsday from 1963 to 1965. Higgins was the first woman to win a Pulitzer Prize for International Reporting in 1951, awarded for her courageous and impactful coverage of the Korean War. Beyond her reporting, she significantly advanced the cause of equal access for female war correspondents, challenging prevailing gender barriers in journalism.

2. Early Life and Education

2.1. Childhood and Family Background

Marguerite Higgins was born on September 3, 1920, in Hong Kong, where her father, Lawrence Higgins, worked for a shipping company. Her Irish-American father met her mother, Marguerite de Godard Higgins, who was of French aristocratic descent, in Paris during World War I. Shortly after their marriage, they moved to Hong Kong, where Marguerite was born. At six months old, she contracted malaria and was taken to a mountain resort in present-day Vietnam for recovery.

Three years later, her family relocated to the United States and settled in Oakland, California. The 1929 stock market crash deeply impacted her family, leading to her father's unemployment and significant financial anxiety. In her autobiography, News Is a Singular Thing, Higgins described that day as the worst of her childhood, stating, "It was on that day that I began worrying about how I'd earn a living when I grew up. I was then eight years old. Like millions of others brought up in the thirties, I was haunted by the fear that there might be no place for me in our society." Despite these hardships, the family persevered. Her father eventually secured a job at a bank, and her mother, by taking a position as a French teacher, was able to secure a scholarship for Higgins to attend the Anna Head School in Berkeley.

2.2. Education and Early Journalism Preparation

In the fall of 1937, Higgins began her studies at the University of California, Berkeley. During her time there, she was a member of the Gamma Phi Beta sorority and contributed to The Daily Californian, the student newspaper, serving as an editor in 1940. She graduated from Berkeley in 1941 with a Bachelor of Arts degree in French.

After graduation, Higgins moved to New York City with the goal of securing a newspaper job, carrying only a single suitcase and 7 USD in her pocket. She initially planned to give herself a year to find employment in journalism, intending to return to California to become a French teacher if unsuccessful. Upon her arrival in late summer 1941, she visited the city office of the New York Herald Tribune and met with city editor L. L. "Engel" Engelking, presenting him with her clippings from student publications. Although he did not offer her a job immediately, he suggested she return in a month. Deciding to remain in New York, she applied to the master's program at the Columbia University Graduate School of Journalism.

Gaining admission to Columbia proved challenging. Days before the program began, she was informed that all slots allotted to women were filled. Through persistent pleading and multiple meetings, the university agreed to consider her application if she could provide all her transcripts and five letters of recommendation from her former professors. Higgins immediately contacted her father to arrange for the necessary materials from Berkeley to be sent to Columbia. Fortuitously, a student dropped out just before the first day of the program, allowing Higgins to enroll.

Initially upset that her classmate, Murray Morgan, had been selected as the coveted campus correspondent for the New York Herald Tribune, Higgins dedicated herself to outperforming her peers, most of whom were men. Her professor, John William Tebbel, noted her exceptional intelligence matched her beauty, describing her as "positively dazzling" and "all hard-edged ambition." Tebbel observed that women in journalism at the time had to be tougher to succeed in the male-dominated and often chauvinistic industry. He remarked that Higgins's driving ambition propelled her to the "outer edge" of toughness, which quickly became apparent to everyone. In 1942, Higgins succeeded her classmate as the campus correspondent for the Tribune, a position that soon led to a full-time reporting role.

3. Journalist Career

3.1. World War II Coverage

Eager to become a war correspondent, Higgins successfully persuaded the management of the New York Herald Tribune to send her to Europe in 1944, just two years after joining the paper. She was initially stationed in London and Paris before being reassigned to Germany in March 1945. In April 1945, she was an eyewitness to the horrific liberation of the Dachau concentration camp. For her assistance during the surrender of the camp's S.S. guards, she was awarded a U.S. Army campaign ribbon. Following the war, she covered the Nuremberg Trials and the Soviet Union's Berlin Blockade. By 1947, her dedication and skill led to her appointment as the chief of the Tribune bureau in Berlin.

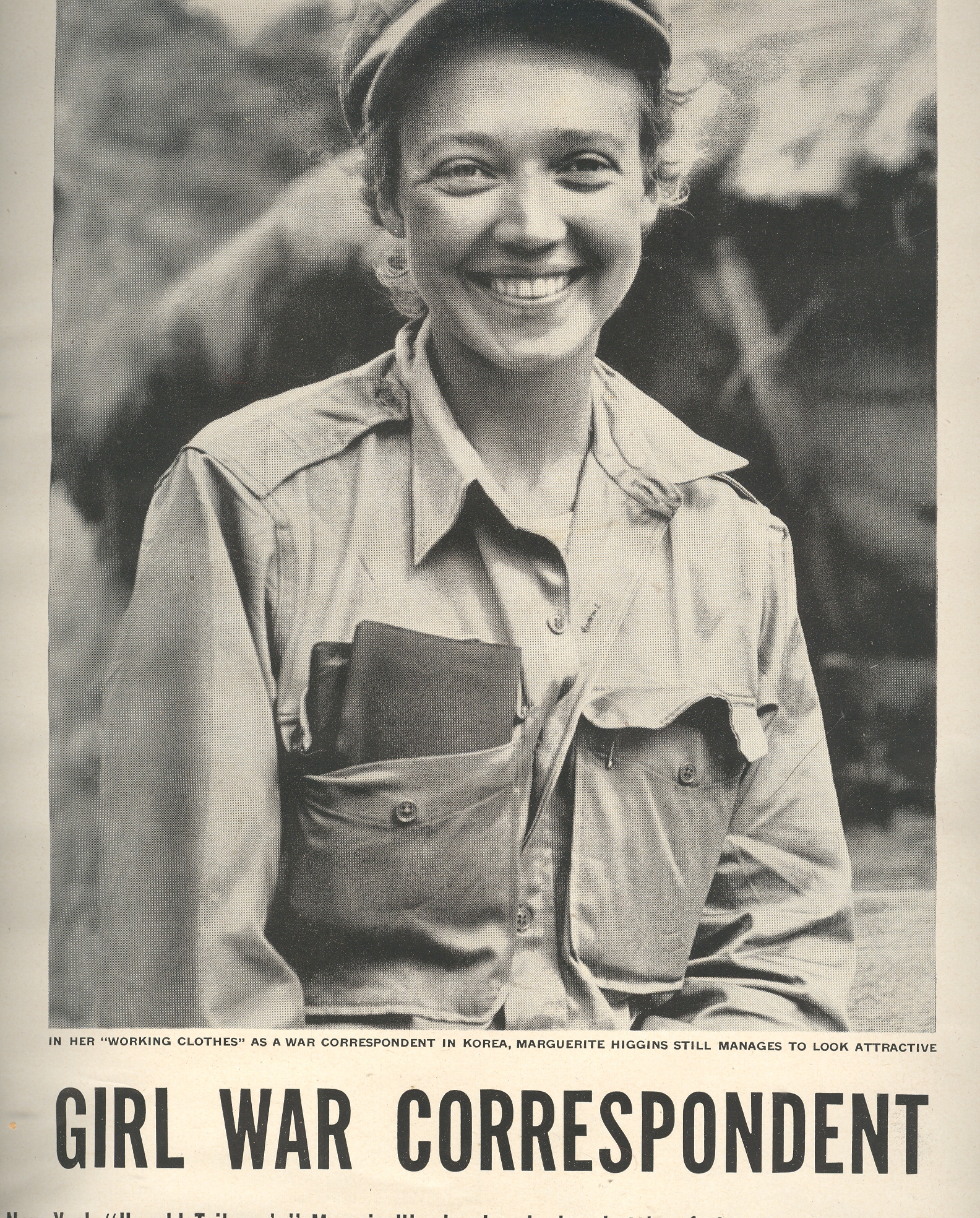

3.2. Korean War Coverage and Pulitzer Prize

In 1950, Higgins was appointed chief of the Tribune's Tokyo bureau. Her arrival was met with a cold reception from her colleagues, a reaction she later attributed to a recently published novel by her former Berlin colleague, Toni Howard. The novel, Shriek With Pleasure, depicted a female reporter in Berlin who stole stories and engaged in sexual relationships with sources, leading to gossip that the character was based on Higgins, thus fostering suspicion and hostility among the Tokyo staff.

Shortly after her arrival in Japan, the Korean War broke out, and Higgins quickly became one of the first reporters on the scene. On June 28, 1950, Higgins and three colleagues witnessed the Hangang Bridge bombing and found themselves trapped on the north bank of the Han River. They managed to cross the river by raft and reached the U.S. military headquarters in Suwon the following day. However, Higgins was promptly ordered out of the country by General Walton Walker, who asserted that women did not belong at the front and that the military lacked the resources to provide separate accommodations for them.

Undeterred, Higgins made a personal appeal to General Douglas MacArthur, Walker's superior officer and the UN Commander. MacArthur subsequently sent a telegram to the Tribune stating: "Ban on women correspondents in Korea has been lifted. Marguerite Higgins is held in highest professional esteem by everyone." This reversal was a significant breakthrough, not just for Higgins, but for all female war correspondents, marking a major step towards equal access in the field. Her initial expulsion and MacArthur's subsequent decision to allow her to remain at the front garnered headlines in the United States, elevating her to a degree of celebrity.

While Higgins was in Korea, the Tribune dispatched Homer Bigart to cover the war, who instructed Higgins to return to Tokyo. She refused, and the Tribune permitted her to stay, igniting a competitive rivalry between the two that would ultimately lead to both receiving the 1951 Pulitzer Prize for International Reporting. They shared the honor with four other male war correspondents. Her Pulitzer Prize was specifically awarded for her coverage of the Inchon Landing, a pivotal event in the Korean War, and not, as is sometimes mistakenly believed, for her subsequent book War in Korea.

3.3. Vietnam War Coverage and International Affairs

Following her groundbreaking reporting from Korea, Higgins received the 1950 George Polk Memorial Award from the Overseas Press Club. She also contributed an article titled "Women of Russia" to Collier's magazine's collaborative special issue, "Preview of the War We Do Not Want", which explored hypothetical scenarios of World War III.

Higgins continued to cover foreign affairs throughout her life, conducting interviews with prominent world leaders such as Francisco Franco, Nikita Khrushchev, and Jawaharlal Nehru. In 1955, she established and became chief of the Tribune's Moscow bureau, making her the first American correspondent permitted to return to the Soviet Union after Stalin's death.

In 1963, she joined Newsday and was assigned to cover South Vietnam. During her time there, she "visited hundreds of villages" and interviewed most of the major political and military figures involved in the conflict. Her experiences and insights were compiled into her book, Our Vietnam Nightmare. While in South Vietnam, Higgins developed another notable rivalry, this time with David Halberstam, a New York Times correspondent who had replaced Bigart. Unlike her competition with Bigart, this feud was rooted in deep ideological differences and personal ego between the seasoned correspondent Higgins and the younger Halberstam.

With two decades of war reporting experience, Higgins's strong anti-Communist sentiments were well-established. She viewed the numerous Buddhist protests against the Ngo Dinh Diem regime as orchestrations by communists. This perspective directly contradicted Halberstam's reporting, who considered Higgins a "past-her-prime sell-out whose anti-Communist views rose to the level of propaganda." Halberstam and many of the younger correspondents in Vietnam at the time were critical of the Diem regime and reported a largely negative view of the war. Higgins, in turn, believed they lacked a true understanding of the conflict, often derisively calling them "Rover Boys" for their perceived reluctance to venture outside Saigon into the countryside to observe the realities of the war. The Higgins-Halberstam rivalry persisted, with Halberstam continuing to criticize her even after her death in 1966.

3.4. Advocacy for Women in Journalism

Marguerite Higgins was a formidable advocate for women in journalism, consistently challenging gender barriers and contributing to the advancement of opportunities and recognition for female war correspondents. From a young age, Higgins exhibited a highly competitive nature, a trait that served her well in the newsroom and during her assignments abroad. Flora Lewis, a classmate of Higgins at Columbia University, recalled her persistence, noting how Higgins would arrive at the library before her classmates to check out all relevant resources for assignments. Lewis reflected on the immense difficulties faced by women in journalism during that era, stating, "I feel that people critical of Maggie and her so-called dirty tricks forget just how hard it was in those days to be a woman in a man's world. The odds were enormous. Even women were against you. They could be so cruel in such subtle ways... Ambition was a dirty word then. Careers were just something you fooled around with until the right man came along. Maggie didn't know that game. She was earnest and played for keeps." Higgins's determination paved the way for future generations of women in a field that was largely unwelcoming to them.

4. Professional Evaluation and Controversy

4.1. Rivalries and Criticism from Colleagues

Marguerite Higgins's professional journey was marked by intense rivalries and criticisms from her male colleagues, reflecting the challenging environment for women in journalism at the time. Her competitive feud with Homer Bigart during the Korean War, which ultimately led to them sharing the Pulitzer Prize, is a notable example of the professional dynamics she navigated. Later, her ideological clashes with David Halberstam in Vietnam highlighted her strong anti-Communist stance and the generational divide among war correspondents.

Some faculty and peers who knew Higgins claimed she leveraged her "sex appeal" to secure difficult interviews or stories. John Tebbel, a Columbia faculty member, specifically recounted an instance where Higgins used her charm to obtain one of the few interviews ever granted by a police commissioner. While Higgins was undeniably eager and willing to do what was necessary to get a story, some of her male colleagues went further, accusing her of performing sexual favors for interviews or information. However, there is no proof to substantiate these accusations. Such allegations were a common form of sexism faced by many high-achieving female correspondents in a male-dominated profession.

4.2. Sexism and Workplace Difficulties

Journalism during Higgins's era was an industry rife with gender discrimination and double standards. Men's sexual behaviors and habits were often deemed irrelevant to their work, and they were rarely criticized for using sexual means to obtain information or stories. According to Carl Mydans, a former photographer for Life magazine, male reporters frequently viewed the world of reporting as their exclusive territory and were often unwilling to share it with women entering the field. Mydans observed, "That a woman would invade the war area-their most sacred domain-and then turn out to be equally talented and sometimes more courageous was something that couldn't be accepted gracefully." Ambitious and high-achieving female journalists like Higgins were frequently subjected to gossip and accusations of sleeping around or using their "sex appeal" to secure the best assignments, sources, or to advance their careers, often with little regard for the truth. Higgins was well aware of these rumors and criticisms from her male peers but chose to disregard them, focusing instead on her work.

4.3. Correction of Misinformation

Over the years, certain factual inaccuracies and myths have circulated regarding Marguerite Higgins's career, particularly concerning her Korean War reporting and Pulitzer Prize.

One widely circulated myth, especially prominent in South Korea since the late 1990s, claimed that Higgins coined the nickname "Ghost-Catching Marines" for the Republic of Korea Marines. This was attributed to a supposed phrase, "They might capture even the devil," in her report on the Tongyeong Landing Operation. This narrative was frequently cited in Marine Corps-related publications and media articles, becoming a widely accepted belief. However, a comprehensive investigation conducted in 2024 by the ROK Marine Corps Military Research Institute, which involved a full review of Higgins's New York Herald Tribune articles, found no evidence of such phrases or any articles written by her specifically about the Tongyeong Landing Operation or the Republic of Korea Marines. Consequently, the "Ghost-Catching Marines" nickname origin story attributed to Higgins has been definitively debunked as a baseless rumor. Following this revelation, the Republic of Korea Marine Corps removed this narrative from its official blogs and social media content in July 2024. Similarly, the Marine Corps Tongyeong Landing Operation Memorial Hall, managed by Tongyeong City, completed the removal of related exhibits in June 2024. Various South Korean government agencies, including the Navy, Ministry of National Defense, Ministry of Patriots and Veterans Affairs, Ministry of Foreign Affairs, Ministry of Personnel Management, Korea Post, and local governments such as Gyeongsangnam-do, Changwon City, and Osan City, also updated or removed their social media content containing this misinformation in June and July 2024.

Another common misconception concerned the specific work for which Higgins received her Pulitzer Prize. While she published a best-selling memoir, War in Korea, in January 1951 based on her six months of reporting, her Pulitzer Prize was awarded for her coverage of the Inchon Landing, specifically the article published in the New York Herald Tribune on September 18, 1950.

Furthermore, despite her iconic status as a Korean War correspondent, Higgins did not cover the entire conflict. She arrived in Korea at the outset of the war on June 27, 1950, and conducted her reporting for approximately six months before returning to the United States in January 1951.

5. Personal Life

While attending the University of California, Berkeley, Marguerite Higgins met Stanley Moore, who was a teaching assistant in the philosophy department. Although they were reportedly attracted to each other, no romantic relationship developed during their time in Berkeley. After Higgins moved to New York, she reconnected with Moore, who was by then a philosophy professor at Harvard University. They married in 1942. However, their relationship deteriorated after Moore was drafted into World War II, and their divorce was finalized in 1947.

In 1952, Higgins married William Evens Hall, a U.S. Air Force major general, whom she had met during her tenure as bureau chief in Berlin. They were married in Reno, Nevada, and initially settled in Marin County, California. Their first daughter, born prematurely in 1953, tragically died five days after birth. In 1958, she gave birth to a son, named Lawrence Higgins Hall, and in 1959, a daughter, Linda Marguerite Hall. By 1963, Hall had retired from the Air Force and began working for an electronics firm, commuting weekly to New York and returning to their home in Washington, D.C. by Friday. Their household included their two children, three cats, two parakeets, a dog, a rabbit, and a donkey.

6. Death and Legacy

6.1. Cause of Death and Funeral

Decades after her childhood bout with malaria in Vietnam, Higgins returned from an assignment in South Vietnam in November 1965. During this assignment, she contracted leishmaniasis, a parasitic disease that ultimately led to her death on January 3, 1966, at the age of 45, in Washington, D.C. She is interred at Arlington National Cemetery alongside her husband.

6.2. Posthumous Recognition and Commemoration

Marguerite Higgins received several significant posthumous honors, particularly from South Korea, acknowledging her contributions to historical memory and her role in publicizing the country's struggle. On November 23, 1946, then Secretary of War Robert P. Patterson honored war correspondents, including Higgins, at an event in Washington, D.C.

On September 2, 2010, the government of South Korea posthumously awarded Marguerite Higgins the Order of Diplomatic Service Merit Heungin Medal (수교훈장 흥인장Sugyohunjang HeunginjangKorean), one of its highest honors. In a ceremony held in Seoul, her daughter and grandson accepted the national medal. The award specifically cited Higgins's bravery in bringing international attention to South Korea's fight for survival in the early 1950s. In 2016, the South Korean Ministry of Patriots and Veterans Affairs further recognized her contributions by naming her the Korean War's "Heroine of May."

6.3. Later Evaluations and Impact

Marguerite Higgins's lasting influence on journalism is profound, particularly her significance as a female pioneer in war reporting. Her determined efforts to gain equal access for women in combat zones broke down significant gender barriers in a male-dominated profession, paving the way for future generations of female correspondents. Her firsthand accounts from World War II, the Korean War, and the Vietnam War provided crucial insights into these conflicts, shaping public understanding and historical narratives. Despite controversies and criticisms she faced during her career, her courage, ambition, and commitment to reporting from the front lines solidified her place as a pivotal figure in the history of war correspondence.

7. Books

Marguerite Higgins authored several major published works, including seminal reports and analyses based on her extensive career as a war correspondent:

- War In Korea: The Report of a Woman Combat Correspondent, 1951

- News Is a Singular Thing, 1955

- Red Plush and Black Bread, 1955

- Our Vietnam Nightmare: The Story of U.S. Involvement in the Vietnamese Tragedy, with Thoughts on a Future Policy, 1965

- Cold War Correspondent: A Korean War Tale, 2021 (This is part of Nathan Hale's Hazardous Tales series, featuring a fictionalized Higgins.)

8. In Popular Culture

Marguerite Higgins has been portrayed or referenced in various media, reflecting her impact and recognition:

- In the 2019 South Korean film The Battle of Jangsari, the fictional character "Maggie," portrayed by Megan Fox, is based on real-life American female war correspondents who covered the Korean War, including Marguerite Higgins and Margaret Bourke-White.

- Phil Pisani's book Maggie's Wars features a main character based on Marguerite Higgins.

- In Nathan Hale's graphic novel Cold War Correspondent, a fictionalized version of Marguerite Higgins appears as the narrator.