1. Overview

Jeanne Bécu, Comtesse du Barry, born Marie-Jeanne Bécu on August 19, 1743, was the last official mistress (maîtresse-en-titre) of Louis XV of France. Rising from humble origins as the illegitimate daughter of a seamstress, she became a prominent figure at the French royal court in Versailles, known for her beauty, charm, and extravagance. Her ascent to such a high position, despite her past as a courtesan, scandalized many in the aristocracy, most notably the young Marie Antoinette. Du Barry's influence, though primarily social and cultural, also touched upon political matters, contributing to the complex dynamics within the monarchy. Following the death of Louis XV in 1774, she was exiled from court. Her life took a dramatic turn during the French Revolution, when she was accused of treason for allegedly assisting émigrés (French aristocrats who fled the Revolution). Despite her pleas, she was convicted by the Revolutionary Tribunal and executed by guillotine on December 8, 1793, becoming one of the many victims of the Reign of Terror. Her story reflects the rigid social stratification of the Ancien Régime and the brutal human impact of the Revolution.

2. Early life and background

Jeanne Bécu's early life was marked by modest circumstances and a gradual ascent through Parisian society, shaped by her beauty and connections.

2.1. Early life and education

Marie-Jeanne Bécu was born on August 19, 1743, in Vaucouleurs, a town in the Champagne region of France. She was the illegitimate daughter of Anne Bécu, a 30-year-old seamstress. The identity of her father remains unconfirmed, though some speculate it may have been Jean Jacques Gomard, a friar known as frère Ange. Shortly after her birth, her mother formed a relationship with Monsieur Billiard-Dumonceaux, a financier, who took both Jeanne and her mother into his care when they moved to Paris. In Paris, Anne worked as a cook for Dumonceaux's mistress, Francesca, who reportedly doted on young Jeanne. Her formal education began at the Convent of St. Aure, located on the outskirts of Paris.

3. Mistress of Louis XV

Jeanne Bécu's tenure as the official mistress of King Louis XV marked a significant period of her life, characterized by her prominent role at the French court and the controversies surrounding her.

3.1. Meeting Louis XV and becoming mistress

Jeanne's growing reputation in Parisian high society brought her to the attention of the Maréchal de Richelieu, who introduced her to Louis XV at Versailles in 1768. The king, still mourning the death of his beloved Queen Marie Leszczyńska in June 1768, was captivated by Jeanne's charm and beauty. He arranged for her to be brought to his boudoir through his valet, Dominique Lebel. However, her humble origins and past as a courtesan made her ineligible to become the official maîtresse-en-titre according to court etiquette. To overcome this obstacle, the king mandated that she marry a man of noble lineage.

On September 1, 1768, Jeanne was hastily married to Comte Guillaume du Barry, the younger brother of her former lover, Jean-Baptiste du Barry. This marriage was accompanied by a false birth certificate, fabricated by Jean-Baptiste du Barry, which made Jeanne appear three years younger (born in 1744 instead of 1743) and concealed her common background by fabricating noble descent. With this marriage, she officially became Comtesse du Barry, gaining the necessary status to be presented at court and recognized as the king's official paramour.

3.2. Court life and influence

Upon her marriage, Jeanne was installed in rooms above the king's quarters, which had previously belonged to Lebel. Her initial days at court were isolating, as she could not be seen publicly with the king until a formal presentation took place. Many members of the nobility, disapproving of her low birth and past, refused to acknowledge her. Louis XV insisted on her formal presentation, and the Duke of Richelieu eventually secured Madame de Béarn as her sponsor by settling her substantial gambling debts. After two failed attempts due to unforeseen circumstances, Jeanne was finally presented at court on April 22, 1769. The event was a spectacle, drawing immense gossip and attention. She wore an extravagant silvery-white gown brocaded with gold, adorned with jewels from the king, and featuring enormous side panniers, a style never before seen. Her elaborate coiffure further delayed the court's waiting.

Jeanne quickly adapted to a life of luxury. She befriended Claire Françoise du Barry, her husband's cultured spinster sister, who had been brought from Languedoc to instruct her in court etiquette. She also cultivated friendships with other noblewomen, such as the Maréchale de Mirepoix, often through generous gifts and favors. Louis XV showered her with lavish gifts, including a young Bengali slave named Zamor, whom she dressed in elegant clothing and began to educate. Zamor, who later testified against her, was likely of Siddi origin and stated his birthplace as Chittagong. Her daily routine at Versailles typically began at 9:00 AM with a cup of chocolate brought by Zamor, followed by selecting gowns and jewelry, and having her hair styled by her hairdresser. She would then receive friends, tradesmen, jewelers, and artists, all eager to offer her their finest wares.

Despite her extravagance, Jeanne was known for her good nature and compassion. When the elderly Comte and Comtesse de Lousene faced execution for debts and for resisting eviction, Jeanne implored the king for their pardon, refusing to rise from her knees until he agreed. Louis XV was moved, remarking, "Madame, I am delighted that the first favour you should ask of me should be an act of mercy!" She also intervened to save a young girl condemned to the gallows for infanticide, demonstrating her capacity for empathy.

As the king's declared mistress, Jeanne became the center of court attention, wearing costly gowns and diamonds that further strained the royal treasury. She made both allies and adversaries. Her most formidable rival was Béatrix, Duchesse de Gramont, who had unsuccessfully sought to replace the late Madame de Pompadour as the king's mistress. Béatrix, along with her brother, the Duc de Choiseul, actively plotted Jeanne's removal, even circulating libelous pamphlets against her and the king.

Jeanne found an ally in the Duc d'Aiguillon, who sided with her against Choiseul. As Jeanne's influence at court grew, Choiseul's waned. Though Louis XV believed France was exhausted after the Seven Years' War, Choiseul advocated for France to support Spain against Britain in the conflict over the Falkland Islands. On Christmas Eve 1770, Du Barry exposed Choiseul's machinations to the king, leading to his dismissal from ministry and exile from court. Despite this political maneuvering, Jeanne herself had little interest in politics, preferring to focus on new gowns and jewelry. However, the king occasionally allowed her to participate in state councils. She was constantly in debt despite a substantial monthly income, at one point receiving up to 3.00 K FRF. She maintained her position as mistress until Louis XV's death, surviving attempts to depose her, including a scheme by the Duc de Choiseul and the Duc d'Aiguillon to arrange a secret marriage between the king and Madame Pater.

3.3. Relationship with Marie Antoinette

The relationship between Madame du Barry and Marie Antoinette, the Dauphine and later Queen, was notoriously contentious and became a significant source of tension at the French court. Their first encounter occurred at a family supper at the Château de la Muette on May 15, 1770, the day before Marie Antoinette's wedding to the Dauphin Louis-Auguste. Despite expectations that Du Barry would be excluded due to her background, she was present, much to the dismay of many attendees. Marie Antoinette, then 14, noticed Du Barry's extravagant appearance and high voice. When informed by the Comtesse de Noailles that Du Barry pleased the king, the archduchess innocently declared she would rival her. The Comte de Provence soon disabused the young princess of her naivety, making her aware of the perceived immorality of Du Barry's position, which further fueled their animosity. Their rivalry intensified, particularly as the Dauphine supported Choiseul, who advocated for the alliance with Austria, a policy opposed by Du Barry's faction.

Marie Antoinette consistently defied court protocol by refusing to speak directly to Madame du Barry. Her disapproval stemmed not only from Du Barry's common background but also from an incident where she heard from the Comte de Provence that Du Barry had laughed heartily at a salacious story told by Cardinal de Rohan about Marie Antoinette's mother, Empress Maria Theresa. Du Barry, furious at the snub, complained to Louis XV, who in turn complained to the Austrian ambassador, Mercy. Concerned about the diplomatic implications, Empress Maria Theresa and Marie Antoinette's brother urged her to reconcile. Eventually, at a ball on New Year's Day 1772, Marie Antoinette reluctantly addressed Du Barry, albeit indirectly, with the famously casual remark: "There are many people at Versailles today." This brief, indirect acknowledgment was enough to ease the immediate tension, though underlying disapproval of Du Barry persisted among many courtiers.

3.4. Diamond Necklace Affair

Madame du Barry was indirectly involved in the infamous Affair of the Diamond Necklace, a scandal that significantly damaged the reputation of the French monarchy and contributed to the public's growing distrust of Marie Antoinette. In 1772, Louis XV, deeply enamored with Du Barry, commissioned Parisian jewelers Boehmer and Bassenge to create a diamond necklace of unparalleled opulence. The estimated cost of this extraordinary piece was 2.00 M FRF.

However, the necklace remained unfinished and unpaid for at the time of Louis XV's death in 1774. Years later, it became the central object of a complex fraud orchestrated by Jeanne de la Motte-Valois. In this scheme, Cardinal de Rohan was led to believe he was purchasing the necklace on behalf of Queen Marie Antoinette, who supposedly desired it but could not openly acquire such an expensive item. The affair, which involved forged letters and secret meetings, ultimately exposed the gullibility of the cardinal and the manipulative nature of de la Motte-Valois. Although Madame du Barry was no longer at court and had no direct involvement in the scandal, the necklace's original commission for her linked it to the perceived extravagance and moral decay of the monarchy. The subsequent public trial and acquittal of Cardinal de Rohan, despite the evidence of fraud, fueled public suspicion against Marie Antoinette and the royal family, further eroding their popularity on the eve of the French Revolution.

4. Exile and later years

Following the death of Louis XV, Madame du Barry faced immediate banishment from court, leading to a period of exile and new personal relationships before the onset of the French Revolution dramatically altered her life.

4.1. Exile after Louis XV's death

As King Louis XV's health deteriorated, he began to contemplate death and repentance, leading him to miss appointments in Jeanne's boudoir. During a stay at the Petit Trianon with her, Louis XV developed the first symptoms of smallpox. He was swiftly brought back to the palace and confined to his bed, where his daughters and Jeanne remained by his side. On May 4, 1774, the king, preparing for confession and Last Rites, suggested that Madame du Barry leave Versailles to protect her from infection. She retired to the Duc d'Aiguillon's estate near Rueil.

Upon the death of Louis XV and the ascension of his grandson, Louis XVI, to the throne, Queen Marie Antoinette promptly ordered Jeanne's exile to the Abbey du Pont-aux-Dames near Meaux-en-Brie. Initially, the nuns at the convent treated her coldly, but they eventually warmed to her timid demeanor and openness, especially the abbess, Madame de la Roche-Fontenelle. After a year at the convent, Jeanne was granted permission to visit the surrounding countryside, provided she returned by sundown. A month later, her freedom was extended, though she was forbidden from venturing within 6.2 mile (10 km) of Versailles, including her beloved Château de Louveciennes. Two years later, she finally received permission to move to Louveciennes permanently.

4.2. Personal relationships and impact of the Revolution

In the years that followed her exile, Madame du Barry formed new romantic relationships. She had a significant liaison with Louis Hercule Timoléon de Cossé-Brissac, the military governor of Paris. She also fell in love with Henry Seymour of Redland, an English nobleman whom she met when he and his family moved to the neighborhood of her château. However, Seymour eventually grew tired of their secret affair and sent a painting to Jeanne with the words "leave me alone" inscribed in English at the bottom. Despite this, the Duc de Brissac remained a faithful companion, keeping Jeanne in his heart even amidst this ménage à trois.

The unfolding French Revolution dramatically impacted her life and those close to her. During the tumultuous period, the Duc de Brissac was captured while visiting Paris and brutally lynched by a revolutionary mob. Late that night, Jeanne heard a drunken crowd approaching the Château de Louveciennes. Through her open window, a blood-stained cloth containing Brissac's severed head was thrown, causing her to faint in shock and horror. The escalating violence and danger of the Revolution prompted her to flee to London in January 1791, where she sought refuge and provided financial assistance to other émigrés.

5. Imprisonment, trial, and execution

The final chapter of Jeanne Bécu's life was marked by her arrest, a politically charged trial, and her ultimate execution during the height of the French Revolution's Reign of Terror.

5.1. Arrest and trial by the Revolutionary Tribunal

During the French Revolution, Jeanne Bécu's slave, Zamor, who had previously been given to her by Louis XV, became a fervent supporter of the revolutionary cause. Zamor, along with another member of Du Barry's domestic staff, joined the Jacobin Club and became a follower of the revolutionary George Grieve, eventually holding office in the Committee of Public Safety. In 1792, Madame du Barry discovered Zamor's deep involvement with Grieve and the revolutionaries, leading her to give him three days' notice to leave her service. In retaliation, Zamor promptly denounced his former mistress to the Committee.

Based largely on Zamor's testimony, Madame du Barry was accused of treason, specifically of financially aiding émigrés who had fled France to escape the Revolution. She was arrested in 1793. When brought before the Revolutionary Tribunal of Paris, she was condemned to death. In a desperate attempt to save her life, she revealed the location of valuable gemstones she had hidden, hoping this information would buy her clemency. However, her efforts were in vain.

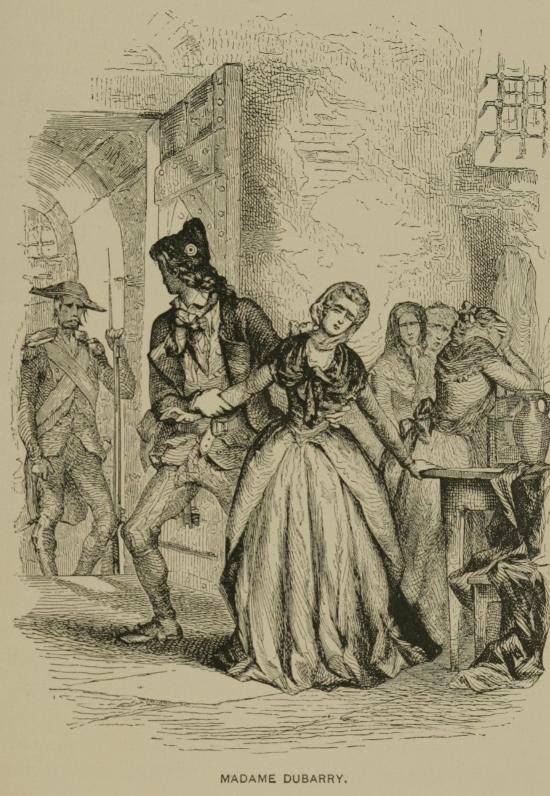

5.2. Final moments and execution

On December 8, 1793, Madame du Barry was transported to the Place de la Révolution (now Place de la Concorde) to be executed by guillotine. On her way to the scaffold, she collapsed in the tumbrel and cried out in terror, "You are going to hurt me! Why?!" She screamed for mercy and desperately begged the watching crowd for help. Her last words, addressed to the executioner, are famously reported as: De grâce, monsieur le bourreau, encore un petit moment!One more moment, Mr. Executioner, I beg you!French Her plea was ignored, and she was beheaded. Her body was subsequently buried in the Madeleine Cemetery, alongside many other victims of the Reign of Terror, including Louis XVI and Marie Antoinette.

Although her French estate was confiscated by the Tribunal de Paris, the valuable jewels she had managed to smuggle out of France to England were sold at an auction at Christie's in London in 1795. The proceeds from this sale were reportedly used by the British to pay Hessian mercenaries who participated in the Battle of Mainz.

6. Evaluation and legacy

Jeanne Bécu, Comtesse du Barry, has been a subject of varied historical assessment, often criticized for her extravagance but also remembered for her unique position and lasting impact on popular culture.

6.1. Historical assessment and criticism

Historically, Madame du Barry has been viewed through a complex lens, often criticized for her perceived extravagance and her humble origins, which many aristocrats found scandalous. Her rise from a courtesan to the king's official mistress was seen by some as a symbol of the moral decay of the French monarchy, further fueling public discontent that contributed to the French Revolution. Her lavish spending on gowns and jewels, despite her significant income, constantly left her in debt and further strained the royal treasury, drawing accusations of draining national resources.

However, some accounts also highlight her good nature, charm, and kindness. She was known for her generosity and her support of artists. The executioner Charles-Henri Sanson reportedly wrote in his memoirs that had more victims of the guillotine cried and begged for their lives as Madame du Barry did, the public might have realized the gravity of the situation sooner, potentially shortening the Reign of Terror. This perspective suggests that her desperate pleas on the scaffold, unlike the stoicism of many other victims, might have humanized the suffering inflicted by the Revolution.

6.2. Cultural impact

Madame du Barry's life and image have left a notable mark on various forms of popular culture, from culinary arts to film and literature.

- Food**: Several dishes bear the name "du Barry," most notably soup du Barry, a creamy white cauliflower soup. This culinary connection is often attributed to Louis XV's fondness for cauliflower, and the white florets are said to allude to Madame du Barry's elaborately powdered and curled hair.

- Château de Louveciennes**: The Château de Louveciennes, gifted to her by Louis XV and renovated by Ange-Jacques Gabriel, became known as "Château de Madame du Barry." After the Revolution, the château fell into disrepair and was eventually sold to a Japanese businessman, Hideki Yokoi, in 1989. However, the property suffered from neglect, theft, and illegal occupation. It has since been purchased by a French investor and restored to its former glory.

- Film**: Madame du Barry has been portrayed in numerous films:

- Mrs. Leslie Carter in the 1915 film DuBarry, directed by Edoardo Bencivenga.

- Theda Bara in the 1917 film Madame Du Barry, directed by J. Gordon Edwards.

- Pola Negri in the 1919 film Madame DuBarry, directed by Ernst Lubitsch.

- Norma Talmadge in the 1930 film Du Barry, Woman of Passion.

- Dolores del Río in the 1934 film Madame Du Barry, directed by William Dieterle.

- Gladys George in the 1938 MGM film Marie Antoinette.

- Lucille Ball in the 1943 movie version of DuBarry Was a Lady.

- Margot Grahame in the 1949 film Black Magic.

- Martine Carol in the 1954 film Madame du Barry, directed by Christian-Jaque.

- Asia Argento in the 2006 film Marie Antoinette, directed by Sofia Coppola.

- Maïwenn in the 2023 film Jeanne du Barry, which she also directed, starring Johnny Depp as Louis XV.

- Literature**:

- In The Idiot by Fyodor Dostoyevsky, the character Lebedev recounts Du Barry's life and execution and prays for her soul.

- Du Barry is a central character in Sally Christie's 2017 novel The Enemies of Versailles.

- She also appears in the manga series The Rose of Versailles by Riyoko Ikeda, Innocent and Innocent Rouge by Shin'ichi Sakamoto, Keikoku no Shitateya Rose Bertin by Hitotsuki Isomi, and Akuyaku Reijō ni Tensei Shita Hazu ga Marie Antoinette Deshita by Yoshito Koide.

- Television**:

- French actress Gaia Weiss portrayed Du Barry in the BBC/CANAL+ 8-part television series Marie Antoinette, where her relationship with Marie Antoinette is a core theme of the first four episodes.

- She also appeared in the 1979-1980 anime adaptation of The Rose of Versailles.

- Opera**:

- Gräfin Dubarry is an operetta in three acts by Carl Millöcker, with a German libretto by F. Zell and Richard Genée.

- La Du Barry is a 1912 opera in three acts by Giannino Antona Traversi and Ernrico Golisciani, with music by Ezio Camussi.

- Other**: She was also known to have favored Houbigant perfumes.