1. Overview

Jeanne Antoinette Poisson, Marquise de Pompadour, commonly known as Madame de Pompadour, was a highly influential member of the French royal court during the reign of Louis XV. Born on 29 December 1721, she served as the King's official chief mistress from 1745 to 1751, maintaining significant influence as a court favourite until her death in 1764. Despite her commoner origins and frail health, Pompadour effectively managed the King's schedule, acting as a valued aide and advisor. She strategically secured titles of French nobility for herself and her relatives, building a robust network of clients and supporters, while carefully fostering a good relationship with Queen Marie Leszczyńska.

Beyond her political role, Madame de Pompadour was a major patron of architecture and the decorative arts, particularly porcelain, and played a central role in establishing Paris as a capital of taste and culture in Europe. She championed French pride through initiatives like the Sèvres porcelain factory. She was also a prominent patron of the philosophes of the Age of Enlightenment, including Voltaire and Denis Diderot, actively defending intellectual freedom. While contemporary critics often portrayed her as a malevolent political influence, driven by fears of her power as a woman not born into the aristocracy, modern historians generally offer a more favorable assessment, emphasizing her successes as an art patron and a champion of French cultural pride. Her life and influence represented a significant shift in existing social and gender hierarchies.

2. Early Life and Background

Jeanne Antoinette Poisson's early life was marked by a unique blend of financial precarity and a privileged education, setting the stage for her remarkable ascent within French society.

2.1. Birth and Family

Jeanne Antoinette Poisson was born on 29 December 1721 in Paris. Her parents were François Poisson (1684-1754) and Madeleine de La Motte (1699-1745). François Poisson, the youngest of nine children, served as a steward to the influential Paris brothers, who were primarily responsible for financing the French economy at the time. However, it is widely suspected that her biological father was either the wealthy financier Jean Pâris de Monmartel or the tax collector (fermier général) Charles François Paul Le Normant de Tournehem.

In 1725, François Poisson was forced to leave France following a scandal involving a series of unpaid debts, a crime punishable by death at the time. During his absence, Le Normant de Tournehem became Jeanne Antoinette's legal guardian, sparing no expense for her upbringing. François Poisson was eventually cleared of the charges eight years later and allowed to return to France. Jeanne Antoinette also had two younger siblings: a sister, Françoise Louise Poisson, born on 15 May 1724, and a brother, Abel-François Poisson, born on 18 February 1727.

2.2. Education and Early Influences

At the age of five, Jeanne Antoinette was sent to an Ursuline convent in Poissy to receive the finest education available. There, she quickly gained admiration for her sharp wit and natural charm. However, due to poor health, believed to be whooping cough, she returned home in January 1730, at the age of nine.

Her mother, Madeleine de La Motte, was determined that her daughter's health issues would not hinder her from becoming a highly educated and accomplished young lady. Upon her return to Paris, Jeanne Antoinette was enrolled in private tutoring, overseen by her legal guardian, Charles François Paul Le Normant de Tournehem, who generously funded her comprehensive education. She received coaching in elocution from an actor of the Comédie-Française and the dramatist Crébillon. The opera singer Jélyotte taught her to sing. Her curriculum also included extensive studies in the humanities, fine arts, music, and social graces, preparing her for a life at court and in high society. This exceptional sponsorship of her education fueled rumors that Le Normant de Tournehem was, in fact, her biological father. During this period, her mother took her to a fortuneteller, Madame de Lebon, who famously predicted that Jeanne Antoinette would one day "reign over the heart of a king." This prophecy led to her being affectionately called "Reinette," meaning "little queen," and she was subsequently groomed for the role of a royal mistress.

3. Marriage and Social Life

Jeanne Antoinette's entry into Parisian society was marked by her marriage and her active engagement with the intellectual and cultural circles of the Enlightenment.

3.1. Marriage

At the age of 20, Jeanne Antoinette married Charles Guillaume Le Normant d'Étiolles (1717-1799) on 15 December 1740. The marriage was arranged by her guardian, Charles Le Normant de Tournehem, who provided substantial financial incentives. On 15 December 1740, Tournehem made his nephew, Charles Guillaume, his sole heir, disinheriting his other nieces and nephews. As a wedding gift, Jeanne Antoinette received the estate at Étiolles, strategically located on the edge of the royal hunting ground of the Forest of Sénart.

By the time of her marriage, Jeanne Antoinette was already well-known in Parisian salons for her beauty, intelligence, and abundant charm. Although her husband, M. Le Normant d'Étiolles, was initially displeased with the arranged marriage, he reportedly fell in love with her swiftly. The union provided both parties with crucial benefits: Le Normant d'Étiolles received a significant dowry that lifted him from relative poverty, while Jeanne Antoinette gained a level of respectability that helped overshadow her mother's questionable past.

The couple appeared to be deeply in love, with Jeanne Antoinette often jesting that she would never leave her husband for anyone, "except, of course, the king." They had a son who died in infancy from tuberculosis in 1742. Their daughter, Alexandrine Le Normant d'Étiolles, born in 1744, tragically died at the age of nine in 1754 from acute peritonitis. Just eleven days after Alexandrine's death, Jeanne Antoinette's father, François Poisson, also passed away, reportedly from depression over the loss of his beloved granddaughter.

3.2. Salons and Intellectual Exchange

As a married woman, Jeanne Antoinette gained access to the celebrated salons of Paris, including those hosted by Mesdames de Tencin, Geoffrin, and du Deffand. Within these influential gatherings, she encountered leading figures of the Age of Enlightenment, such as Voltaire, Charles Pinot Duclos, Montesquieu, Claude Adrien Helvétius, and Bernard Le Bovier de Fontenelle.

Beyond attending these prominent salons, Jeanne Antoinette established her own at Étiolles, which attracted many of the cultural elite, including Crébillon fils, Montesquieu, the Cardinal de Bernis, and Voltaire. Through her participation and hosting of these intellectual exchanges, she honed the fine art of conversation and developed the sharp wit for which she would later become renowned at Versailles. These experiences provided her with invaluable social and intellectual capital, preparing her for her future role at the heart of the French court.

4. Royal Mistress and Court Life

Jeanne Antoinette Poisson's transformation into the Marquise de Pompadour marked her official entry into the French court and her establishment as the most powerful woman in France outside the royal family.

4.1. Meeting the King

Due to her prominence in Parisian salons and her captivating grace and beauty, Louis XV had heard of Jeanne Antoinette as early as 1742. In 1744, eager to attract the King's attention, Jeanne Antoinette deliberately sought him out during his hunt in the Forest of Sénart, near her Étiolles estate. She strategically drove her carriage directly into the King's path, once in a pink phaeton wearing a blue dress, and another time in a blue phaeton wearing a pink dress. The King, intrigued, sent her a gift of venison.

The opportunity for her to formally enter the King's life arose on 8 December 1744, when his current mistress, Madame de Châteauroux, unexpectedly died. On 24 February 1745, Jeanne Antoinette received a formal invitation to the masked ball held on 25 February at the Palace of Versailles, celebrating the marriage of the Dauphin Louis of France to Infanta Maria Teresa Rafaela of Spain. It was at this ball that Louis XV, disguised along with seven courtiers as yew trees, publicly revealed his affection for Jeanne Antoinette. She was dressed as Diana the Huntress, a direct reference to their earlier encounter in the forest, solidifying their connection before the entire court and royal family.

4.2. Official Status and Influence

By March 1745, Jeanne Antoinette had become the King's mistress and was immediately installed in an apartment at Versailles, directly above his own. On 7 May, her official separation from her husband, Charles Guillaume Le Normant d'Étiolles, was pronounced. To be formally presented at court, she required a noble title. The King purchased the marquisate of Pompadour on 24 June 1745, bestowing the estate, title, and coat-of-arms upon Jeanne Antoinette, thereby making her a Marquise.

On 14 September 1745, Madame de Pompadour made her formal entry before the King, presented by his cousin, the Princess of Conti. Determined to secure her position, she immediately sought to forge a good relationship with the royal family. When Queen Marie Leszczyńska engaged her in conversation, Pompadour responded with delight, swearing her respect and loyalty to the Queen. In return, the Queen favored Jeanne Antoinette over the King's previous mistresses. Pompadour quickly mastered the intricate and highly mannered court etiquette. However, her mother, Madeleine de La Motte, died on Christmas Day of the same year, never witnessing her daughter's full achievement as the undisputed royal mistress.

Her influence grew steadily. On 12 October 1752, she was elevated to the rank of duchess, and in 1756, she was named the thirteenth lady-in-waiting to the Queen, the most prestigious position a woman could hold at court. This accorded her significant honors and further cemented her status. As the King's favorite, Pompadour wielded considerable power, effectively acting as a prime minister. She became responsible for managing the King's schedule, influencing appointments, granting favors, and orchestrating dismissals, thereby playing a crucial role in both domestic and foreign politics.

4.3. Relationship with Royal Family

Madame de Pompadour was particularly careful not to alienate the popular Queen Marie Leszczyńska. Her efforts to establish a respectful relationship with the Queen were successful, leading the Queen to favor Pompadour over other mistresses of the King. This strategic approach helped stabilize her precarious position at court.

However, her commoner background remained a source of tension with other members of the royal family and the aristocracy. The Dauphin, Louis Ferdinand, openly disrespected her due to her non-aristocratic origins. Despite these challenges, Pompadour's mastery of court etiquette and her indispensable role to the King allowed her to navigate the complex social dynamics of Versailles.

4.4. Role as King's Friend

Around 1750, Madame de Pompadour's relationship with Louis XV evolved, and she ceased her sexual intimacy with the King, transitioning to a role primarily as his friend and confidante. This shift was partly attributed to her persistent poor health, which included the aftereffects of whooping cough, recurring colds and bronchitis, bouts of spitting blood, severe headaches, and three miscarriages attributed to the King. She also suffered from an unconfirmed case of leucorrhoea and admitted to having a "very cold temperament," with attempts to increase her libido using a diet of truffles, celery, and vanilla proving unsuccessful.

Furthermore, the Jubilee year in 1750 placed significant pressure on the King to repent for his sins and renounce his mistress. To counteract these impediments and solidify her continued importance as the King's favorite, Pompadour deliberately cultivated her new role as the "friend of the King." This transition was notably announced through her artistic patronage, most prominently through her commission of a sculpture from Jean-Baptiste Pigalle, which depicted herself as Amitié (Friendship), offering herself to a now-lost pendant sculpture of Louis XV. A related sculpture was also depicted in a 1759 portrait of her by François Boucher.

In this new capacity, Pompadour became invaluable to Louis XV, who was prone to melancholy and boredom. She was the only person he fully trusted and who could be relied upon to tell him the truth. She captivated and amused him, entertaining him with elegant private parties, operas, afternoons of hunting, and journeys among their various châteaux and lodgings. She would even, with the King's help, sometimes invite Queen Marie Leszczyńska to these gatherings, further demonstrating her unique and indispensable position.

5. Political Activities and Influence

Madame de Pompadour's tenure at court was marked by her deep and active involvement in the political landscape of France, extending her influence far beyond the traditional role of a royal mistress.

5.1. Advisor and Diplomat

Through her position as the King's favorite, Pompadour effectively functioned as a de facto prime minister, wielding considerable power and influence over state affairs. She was responsible for managing Louis XV's schedule, controlling access to the King, and playing a decisive role in appointments, favors, and dismissals within the court and government. Her keen political mind and close relationship with the King allowed her to contribute significantly to both domestic and foreign policy decisions.

Her diplomatic involvement became particularly evident in 1755 when Wenzel Anton, Prince of Kaunitz-Rietberg, a prominent Austrian diplomat, sought her intervention in negotiations that ultimately led to the Treaty of Versailles. This marked the beginning of the Diplomatic Revolution, a significant realignment of European alliances that saw France ally with its former enemy, Austria.

5.2. Impact on Foreign Policy

Under these new alliances, the European powers entered the Seven Years' War, which pitted France, Austria, and Russia against Britain and Prussia. Pompadour played a role in forming this anti-Prussian coalition, communicating with Maria Theresa of Austria and Elizabeth of Russia. However, the war proved disastrous for France, culminating in a defeat at the Battle of Rossbach in 1757 and the eventual loss of the American colonies to the British. Following the defeat at Rossbach, Madame de Pompadour is famously alleged to have consoled the King with the phrase: "au reste, après nous, le Déluge" (au reste, après nous, le DélugeBesides, after us, the DelugeFrench), a remark that has been interpreted as a cynical prediction of future decline. France emerged from the war diminished and virtually bankrupt, a outcome for which Pompadour was often blamed by her contemporaries.

Despite the criticisms, Madame de Pompadour persisted in her support of these foreign policies. When Cardinal de Bernis failed to meet her expectations, she strategically brought Choiseul into office, supporting and guiding him in his key initiatives, including the Pacte de Famille, the suppression of the Jesuits, and the Treaty of Paris (1763).

5.3. Domestic Policy and Appointments

Domestically, Pompadour's influence extended to various policy areas and key appointments. She notably protected the Physiocrats school of economic thought, whose leader, François Quesnay, was her personal physician. This support helped pave the way for later economic theories, including those of Adam Smith.

She was also a staunch defender of the Encyclopédie, edited by Denis Diderot and Jean le Rond d'Alembert, against attempts by figures like the Archbishop of Paris Christophe de Beaumont to suppress it. Diderot, in his first novel Les bijoux indiscrets (The Indiscreet Jewels), portrayed Pompadour in a flattering light, likely to secure her continued support for the Encyclopédie. The fact that Pompadour had a copy of Les bijoux indiscrets in her personal library may explain why the crown did not pursue Diderot for such an indiscretion against the King.

Her political acumen was also evident in her extensive book collection, which included influential works like the History of the Stuarts, printed in 1760 with her own printing press, identifiable by the stamp of her arms on the cover. She also played a significant role in key appointments, notably securing the post of Directeur Général des Bâtiments for her brother, Abel-François Poisson, which gave him control over government policy and expenditures for the arts.

6. Patronage of Arts and Culture

Madame de Pompadour was an unparalleled patron of the arts and culture, profoundly shaping the aesthetic and intellectual landscape of 18th-century France. Her influence was instrumental in establishing Paris as the cultural capital of Europe.

6.1. Patronage of Artists and Crafts

Her extensive support for various art forms was facilitated by the appointment of her guardian, Charles François Paul Le Normant de Tournehem, and later her brother, Abel-François Poisson, to the prestigious position of Directeur Général des Bâtiments, which oversaw all government policy and expenditures related to the arts.

Pompadour championed French pride by actively promoting and, in 1759, outright purchasing a porcelain factory at Sèvres. Under her guidance, Sèvres became one of the most renowned porcelain manufacturers in Europe, providing skilled jobs and producing exquisite pieces, including the distinctive "Pompadour Rose" pink. Her personal collection of decorative items, including porcelain, was vast, with her sudden death requiring a year to catalog all her possessions.

She patronized numerous sculptors and portrait painters, including the court artist Jean-Marc Nattier, and in the 1750s, François Boucher, Jean-Baptiste Réveillon, and François-Hubert Drouais. She also supported Jacques Guay, a gemstone engraver, who taught her to engrave in onyx, jasper, and other semi-precious stones.

Pompadour significantly influenced and stimulated innovation in the Rococo style in both fine and decorative arts. This was evident through her patronage of artists like Boucher and the constant redecoration of the fifteen residences she held with Louis XV. Although some critics, including her contemporaries, viewed Rococo as a pernicious "feminine" influence, it was widely embraced by both men and women. Her engagement with prominent artists was also a strategic way to maintain the King's attention while cultivating her public image. For instance, an oil sketch of Pompadour's lost portrait by Boucher at Waddesdon Manor is surrounded by Sèvres porcelain, demonstrating her impact on the industry through her international network of clientele.

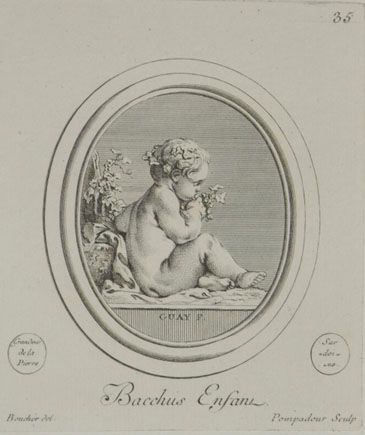

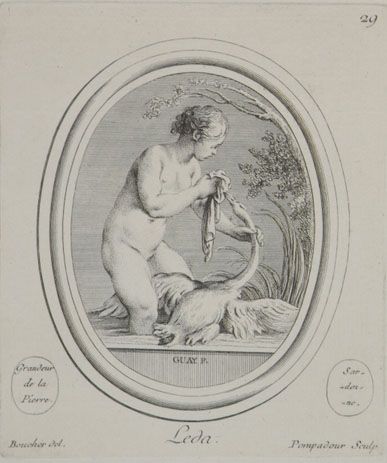

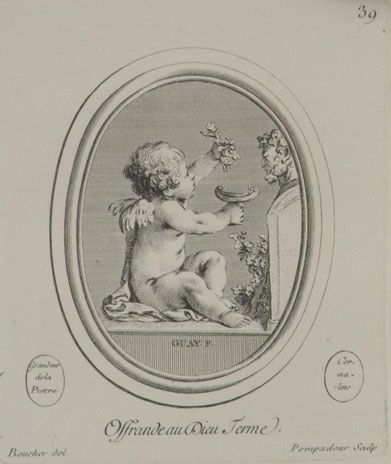

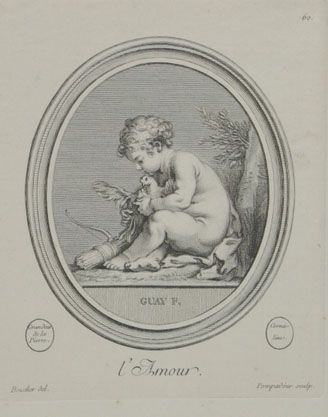

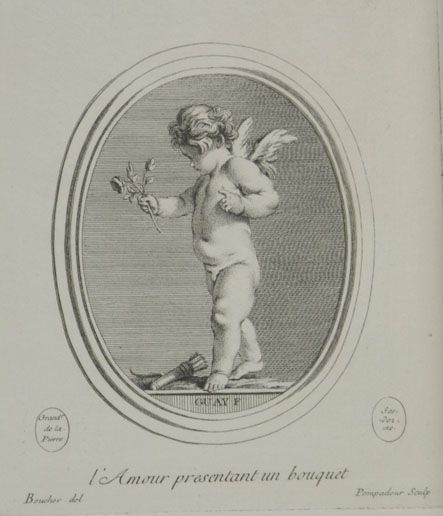

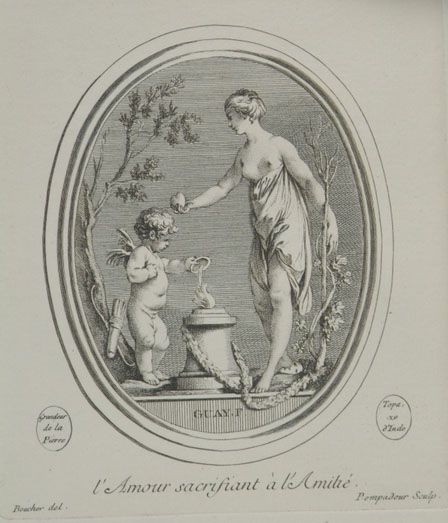

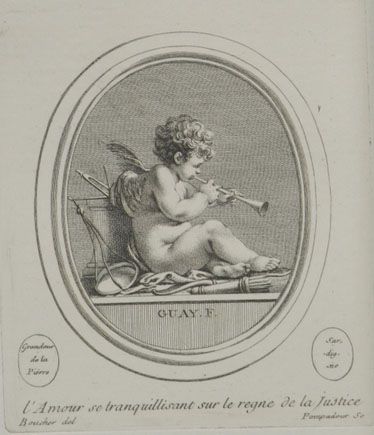

Beyond being a patron, Pompadour directly participated in the arts. She was one of the few 18th-century practitioners of gem engraving and an acclaimed stage actress, performing in plays at her private theaters at Versailles and Bellevue. Some artworks created under her purview, such as Boucher's 1758 portrait of Mme de Pompadour at Her Toilette, are considered collaborations with her. She was also an amateur printmaker, creating 52 engraved prints of drawings by Boucher, after gemstone engravings by Guay. Her engraving equipment was even brought into her personal apartments at Versailles. Her collected work of prints is titled Suite d'Estampes Gravées Par Madame la Marquise de Pompadour d'Apres les Pierres Gravées de Guay, Graveur du Roy (Suite d'Estampes Gravées Par Madame la Marquise de Pompadour d'Apres les Pierres Gravées de Guay, Graveur du RoySeries of Prints engraved by Madame la Marquise de Pompadour after the engraved stones of Guay, engraver of the KingFrench). A personal portfolio of her engravings was discovered in the Walters Art Museum manuscript room by art historian Susan Wager.

Her personal portfolio of engravings is held in several museums and libraries, including:

- Walters Art Museum, Baltimore

- Met Museum, New York

- British Museum, London

- Boston Museum of Fine Arts

- Bibliothèque de l'Arsenal, Paris

- Rothschild collection, Louvre

- Bibliothèque de Troyes

These engravings showcase her skill and collaboration with artists like Boucher and Guay:

Her collection includes various mythological and allegorical subjects:

These works demonstrate her deep engagement with the artistic trends of her time:

Further examples from her portfolio highlight themes of love and friendship:

6.2. Support for Enlightenment Thinkers

Madame de Pompadour actively supported the leading philosophes of the Enlightenment. Her salons were frequented by intellectual giants such as Voltaire, Denis Diderot, Montesquieu, and Bernard Le Bovier de Fontenelle. She played a crucial role in defending the Encyclopédie, a monumental work of the Enlightenment, against attempts by conservative figures, including the Archbishop of Paris, to suppress it. Her patronage provided a vital shield for these thinkers, allowing them to pursue and disseminate their ideas, which were often controversial.

6.3. Architecture and Residences

Pompadour's passion for architecture and interior design was evident in her numerous residences, which she continuously redecorated and managed. These homes served as centers of cultural and political influence. Among her notable properties were the Élysée Palace (which Louis XV gifted to her), the Château de Saint-Ouen, the Château de Crécy, the Château de Bellevue, the Château de La Celle, and the Château de Menars.

The Château de Saint-Ouen, built in the 17th century, became one of her significant projects. From 1759 until her death in 1764, she held the usufruct of this residence. The original U-shaped plan by Antoine Lepautre featured a long façade and two wings facing the Seine. Its interior was unique for its three "salons à l'italienne" (rooms extending the full height of the building), which had been redecorated by the Slodtz family in the 1750s. Upon acquiring the estate, Pompadour initiated a vast reorganization project for all the buildings, including stables and dependencies, costing over 500.00 K FRF. The architect supervising this ambitious work was Ange-Jacques Gabriel, who oversaw all renovation and building projects for her residences. By using the central "salon à l'italienne" as a pivot, an apartment was created for the King, mirroring Pompadour's own, transforming the prestigious Château de Saint-Ouen into a symbol of her elevated social and political status.

6.4. Fashion and Personal Style

Madame de Pompadour was a formidable trendsetter, and her personal style significantly influenced contemporary fashion, hairstyles, and decorative arts within French society. Her exquisite taste became the standard of elegance. The famous "Pompadour hairstyle", characterized by hair swept up from the face and worn high over the forehead, was named after her.

Her influence extended even to everyday items. The ""coupe de champagne"" (French champagne glass) is sometimes anecdotally claimed to have been modeled on the shape of her breast, though this is likely a popular myth rather than historical fact. Similarly, the "marquise cut" diamond, also known as "navette," is said to have been commissioned by Louis XV to resemble the shape of Madame de Pompadour's mouth. These anecdotes, whether true or not, illustrate the pervasive nature of her influence on aesthetics and luxury.

7. Personal Life and Health

Madame de Pompadour's private life was marked by persistent health challenges and the profound sorrow of losing her children, which deeply impacted her well-being and her relationship with the King.

7.1. Health Issues

Throughout her life, Madame de Pompadour endured various illnesses and health problems that significantly affected her personal well-being and public activities. She suffered from the lingering aftereffects of whooping cough from childhood, recurring colds, and chronic bronchitis, often accompanied by spitting blood. She also experienced frequent headaches and an unconfirmed case of leucorrhoea. These physical ailments led to her admitting to having a "very cold temperament" and experiencing frigidity, which contributed to the cessation of her sexual relationship with Louis XV around 1750. Attempts to increase her libido with a diet of truffles, celery, and vanilla proved unsuccessful. Her frail constitution and chronic health issues were a constant struggle, ultimately leading to her early death.

7.2. Family and Children

Madame de Pompadour's personal life was also deeply affected by the loss of her children. She had two children with her husband, Charles Guillaume Le Normant d'Étiolles. Their first child, a son named Charles Guillaume Louis, born in 1741, tragically died in infancy in 1742 from tuberculosis. Their daughter, Alexandrine Le Normant d'Étiolles, born in 1744, died at the tender age of nine in 1754 from acute peritonitis. The death of Alexandrine was a profound blow, and just eleven days later, her own father, François Poisson, passed away, reportedly from the grief of losing his beloved granddaughter. These personal tragedies undoubtedly added to the emotional and physical strain on Madame de Pompadour throughout her life.

8. Assessment and Controversy

Madame de Pompadour's remarkable rise from commoner to the King's chief mistress and political confidante inevitably generated intense contemporary scrutiny and ongoing historical debate.

8.1. Contemporary Assessment and Criticism

During her lifetime, Madame de Pompadour faced significant criticism and hostility, particularly from her contemporaries within the royal court and among political opponents. Many aristocratic courtiers viewed her presence as a disgrace, believing it compromised the King's dignity to associate so closely with a commoner. She was often "tarred as a malevolent political influence" and accused of meddling excessively in state affairs.

She was highly sensitive to the unending libels and lampoons directed at her, known as poissonnades, a pun on her family name, Poisson, which means "fish" in French. These attacks were analogous to the Mazarinade against Cardinal Mazarin. Despite her distress, Louis XV was often reluctant to take punitive action against her known enemies, such as Louis François Armand du Plessis, duc de Richelieu.

One of the most persistent and damaging criticisms leveled against her was the accusation that she acted as a "pimp" for the King, providing him with young women for his private pleasure.

8.2. Historical Assessment

In contrast to the often-hostile contemporary views, historians have generally offered a more favorable assessment of Madame de Pompadour's legacy. They tend to emphasize her significant successes as a patron of the arts and a champion of French pride. Modern historians suggest that the intense criticism she faced was largely driven by fears among the established aristocracy over the overturning of existing social and gender hierarchies, which Pompadour's power and influence, as a woman not born into the aristocracy, represented. While acknowledging her political involvement, many historians now highlight her contributions to French culture and her role in supporting the Enlightenment.

8.3. Controversies

Several aspects of Madame de Pompadour's life have remained subjects of controversy and debate.

One such controversy revolves around the Parc-aux-Cerfs, a house in Versailles where Louis XV met with young women. Contrary to popular belief, it was not a harem but typically housed only one woman at a time. Madame de Pompadour's involvement in the Parc-aux-Cerfs was minimal; she was not directly involved in procuring women but accepted its existence as a "necessity" and a favorable alternative to having a rival mistress at court. She famously stated, "It is his heart I want! All these little girls with no education will not take it from me. I would not be so calm if I saw some pretty woman of the court or the capital trying to conquer it." This indicates her strategic acceptance of the arrangement to maintain her unique position as the King's confidante rather than a sexual partner.

Another significant controversy concerned her alleged conflict with the Jesuits. It is claimed that Pompadour harbored a deep resentment towards the Jesuit order because their priests refused to recognize her and Louis XV as an official couple, given their extramarital relationship. Some historians argue that she exerted considerable influence in the eventual expulsion of the Jesuits from France, particularly after the Lavalette bankruptcy scandal. However, other analyses suggest that the Jesuits' expulsion was more a consequence of their own internal issues and their involvement in various political intrigues, such as the assassination attempts on the King, rather than solely Pompadour's personal vendetta.

9. Death

Louis XV remained deeply devoted to Madame de Pompadour until her death on 15 April 1764, at the age of 42. She succumbed to tuberculosis, specifically pulmonary congestion, after a prolonged illness. The King personally nursed her through her final, painful weeks, and even her political enemies admired her courage during this period.

The philosopher Voltaire, a beneficiary of her patronage, expressed his sorrow, writing: "I am very sad at the death of Madame de Pompadour. I was indebted to her and I mourn her out of gratitude. It seems absurd that while an ancient pen-pusher, hardly able to walk, should still be alive, a beautiful woman, in the midst of a splendid career, should die at the age of forty-two." Many of her enemies, however, felt a sense of relief at her passing.

As her coffin departed from Versailles on a rainy day, the devastated King reportedly remarked, "La marquise n'aura pas de beau temps pour son voyage" (La marquise n'aura pas de beau temps pour son voyageThe marquise will not have good weather for her journeyFrench). She was buried at the Couvent des Capucines in Paris.

10. Legacy and Influence

Madame de Pompadour's legacy extends far beyond her role as a royal mistress, encompassing profound and lasting impacts on French politics, culture, and society. For nearly two decades, she wielded immense power, effectively acting as a "shadow ruler" or a de facto prime minister. Her influence was instrumental in key political decisions, including the significant realignment of European alliances during the Diplomatic Revolution and the strategic direction of France during the Seven Years' War, even though the latter proved disastrous for France. She also played a crucial role in domestic policy, notably supporting the Physiocrats and defending the Encyclopédie, thereby contributing to the intellectual ferment of the Enlightenment.

Culturally, Pompadour's impact was transformative. She was a major patron of the arts, fostering the elegant Rococo style and supporting countless artists, architects, and artisans. Her establishment and promotion of the Sèvres porcelain factory not only created skilled jobs but also produced some of Europe's most exquisite and famous porcelain. Her personal involvement in art, from collecting to practicing gem engraving and printmaking, demonstrated her deep engagement with creative pursuits. She also set trends in fashion and personal style, with the "Pompadour hairstyle" and the "marquise cut" diamond bearing her name. Her extensive book collection and her personal portfolio of engravings further underscore her intellectual curiosity and direct participation in the cultural sphere. Through her salons and her patronage, she cultivated an environment where intellectual and artistic endeavors flourished, solidifying Paris's reputation as a center of culture and taste.

11. Portrayals in Popular Culture

Madame de Pompadour's captivating life and influential role have inspired numerous portrayals across various forms of popular culture, from film and television to literature and other media.

11.1. Film and Television

Madame de Pompadour has been frequently depicted on screen. Notable portrayals include:

- Paulette Duval in Monsieur Beaucaire (1924)

- Dorothy Gish in Madame Pompadour (1927)

- Anny Ahlers in Madame Pompadour (1931)

- Doris Kenyon in Voltaire (1933)

- Jeanne Boitel in Remontons les Champs-Élysées (1938)

- Hillary Brooke in Monsieur Beaucaire (1946)

- Geneviève Page in Fanfan la Tulipe (1952)

- Micheline Presle in Royal Affairs in Versailles (1954)

- Monique Lepage in Le Courrier du roy (1958)

- Elfie Mayerhofer in Madame Pompadour (1960)

- Noëmi Nadelmann in Madame Pompadour (1996)

- Katja Flint in Il giovane Casanova (2002)

- Hélène de Fougerolles in Fanfan la Tulipe (2003) and Jeanne Poisson, marquise de Pompadour (TV, 2006)

- Sophia Myles (as an adult) and Jessica Atkins (as a child) in "The Girl in the Fireplace", an episode of the BBC science fiction series Doctor Who (2006)

- Bojana Novakovic in Casanova (2015)

11.2. Literature and Other Media

Madame de Pompadour's presence in popular culture extends beyond film and television:

- The 56th (West Essex) Regiment of Foot, a unit of the British Army from 1755 to 1881, was nicknamed "The Pompadours" because the purple facing of their uniform was allegedly her favorite color, or, as some soldiers preferred to claim, the color of her underwear. Its successor, the Essex Regiment, maintained the color and the nickname.

- The Madame Pompadour is a German operetta with music by Leo Fall and libretto by Rudolph Schanzer and Ernst Welisch. It had successful adaptations in London (1923) and on Broadway, where it opened the Martin Beck Theatre in 1924.

- She was the subject of several portraits throughout her lifetime, including those by François Boucher and Maurice Quentin de La Tour.

- According to legend, the "marquise cut" diamond, also called "navette," is said to have been commissioned by Louis XV to resemble the shape of Madame de Pompadour's mouth.

- The Pompadour hairstyle was named after her.

- In the second act of Tchaikovsky's opera The Queen of Spades, the Countess recalls the great names of artists from her past, mentioning "and sometimes even the Marquise de Pompadour in person!"

- She is mentioned in the opening line of the Johnny Mercer song "Personality," featuring the Pied Pipers.

- She is a main character in the Doctor Who episode "The Girl in the Fireplace".

- She is the subject of several historical novels, including Kano wa Pompadour (かの名はポンパドールHer Name is PompadourJapanese) by Kenichi Sato and Poisson ~ Jōki Pompadour no Shōgai (ポワソン~寵姫ポンパドゥールの生涯Poisson ~ The Life of the Favorite Concubine PompadourJapanese).

- The Japanese bakery chain "Pompadour" is named after her.

- The "Rose Pompadour" is a rose cultivar from the French company Delbard.

- She is associated with Houbigant, a perfume house, having been involved in the manufacturing of one of her favorite perfumes.