1. Overview

Leigh Hunt was a significant literary figure of the 19th century, known for his diverse contributions as a poet, essayist, journalist, and critic. He co-founded and edited The Examiner, an influential intellectual journal that espoused radical principles and offered independent commentary on society and politics. Hunt was at the heart of the "Hunt circle," a group of intellectuals and artists based in Hampstead that included notable figures like William Hazlitt and Charles Lamb. He is also credited with introducing prominent poets such as John Keats and Percy Bysshe Shelley to the public, as well as later figures like Robert Browning and Alfred Tennyson. His career was marked by his advocacy for progressive ideas, which sometimes led to controversy, most notably his two-year imprisonment for libel against the Prince Regent. Despite persistent financial struggles throughout his life, Hunt maintained a prolific literary output, including significant poetic works like Story of Rimini and his comprehensive Autobiography. His impact on literature and culture is further evidenced by his depiction as the character Harold Skimpole in Charles Dickens' novel Bleak House.

2. Early Life and Education

Leigh Hunt's formative years were shaped by his family's unique background and his early educational experiences, which fostered his intellectual development despite personal challenges.

2.1. Birth and Background

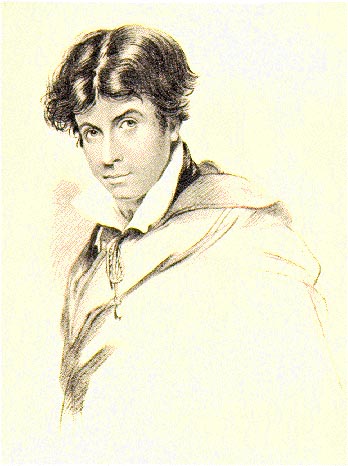

James Henry Leigh Hunt was born on 19 October 1784, in Southgate, London. His parents, Isaac Hunt and Mary Shewell, had settled in Britain after being compelled to leave the United States due to their Loyalist sympathies during the American War of Independence. His father, Isaac, was a lawyer from Philadelphia, and his mother, Mary Shewell, was a merchant's daughter and a devout Quaker. After their arrival in England, Isaac Hunt became a popular preacher, though he struggled to secure a permanent position. He later served as a tutor to James Henry Leigh, the nephew of James Brydges, 3rd Duke of Chandos, and named his son after him.

2.2. Education

Hunt received his education at Christ's Hospital in London, attending from 1791 to 1799. He later recounted this period in detail within his autobiography. During his time at Christ's Hospital, Thomas Barnes was a school friend. In recognition of his contributions, one of the boarding houses at Christ's Hospital was later named after Hunt. As a boy, Hunt developed an early admiration for poets such as Thomas Gray and William Collins, producing many verses in imitation of their styles, which showcased his nascent poetic voice. A speech impediment, which was later cured, unfortunately prevented him from pursuing a university education. Hunt described this period, stating that for some time after leaving school, he "did nothing but visit my school-fellows, haunt the book-stalls and write verses." His initial poetic endeavors were published in 1801 under the title of Juvenilia, which served as his introduction to British literary and theatrical society. He subsequently began writing for newspapers and in 1807 published a volume of theatre criticism, alongside a series of Classic Tales which included critical essays on various authors. His early essays were published by Edward Quin, who was the editor and owner of The Traveller.

3. Journalism and Critical Work

Leigh Hunt's career was extensively dedicated to journalism and literary criticism, through which he championed progressive ideas and significantly influenced the periodical landscape of his era.

3.1. The Examiner

In 1808, Hunt resigned from his position as a clerk at the War Office to assume the editorship of The Examiner, a newspaper founded by his brother, John Hunt. His other brother, Robert Hunt, also contributed to its columns. The Examiner quickly established a reputation for its exceptional political independence, known for criticizing any deserving target "from a principle of taste," as John Keats famously described it. This independent stance, however, also drew enmity; William Blake notably described the office of The Examiner as containing a "nest of villains," a criticism that extended to Leigh Hunt himself, who had published several scathing reviews in 1808 and 1809 and had included Blake's name on a list of so-called "quacks." In 1813 (or 1812, according to some accounts), The Examiner published a sharp attack on Prince Regent George, describing his physique as "corpulent." This led to the prosecution of the three Hunt brothers by the British government, resulting in a two-year prison sentence. Leigh Hunt served his term at the Surrey County Gaol.

From 1814 to 1817, Leigh Hunt collaborated with William Hazlitt on a series of essays for The Examiner, which they titled "The Round Table." These essays were subsequently published in two volumes in 1817 under the collective title The Round Table. Of the 52 essays included, twelve were penned by Hunt, with Hazlitt contributing the remainder.

3.2. Other Periodicals

Beyond The Examiner, Hunt engaged in editorial work for several other significant periodicals, each contributing to the literary and intellectual discourse of the time. From 1810 to 1812, he edited a quarterly magazine called The Reflector for his brother John. During this period, he wrote The Feast of the Poets, a satirical work that caused offense among many contemporary poets, notably William Gifford. From 1819 to 1821, Hunt edited The Indicator, a weekly literary periodical published by Joseph Appleyard. He is believed to have written a substantial portion of its content, which encompassed reviews, essays, stories, and poems. Later, from January to July 1828, Hunt edited The Companion, another weekly literary periodical published by Hunt and Clarke. This journal focused on books, theatrical productions, and a variety of miscellaneous topics.

3.3. Essays and Literary Criticism

Hunt was a prolific essayist and literary critic, producing a wide array of works that included literary reviews and theatre criticism. His collaborative efforts, such as "The Round Table" with William Hazlitt, showcased his critical style and insights. His writings often demonstrated a light touch and versatility, allowing him to discuss a wide range of issues and establish himself as a prominent literary journalist and practical publisher.

4. Poetry

Leigh Hunt's poetic endeavors spanned his career, marked by an evolving style and thematic depth that contributed to the Romantic movement.

4.1. Early Poetic Efforts

Hunt's initial foray into poetry began with Juvenilia, published in 1801, which introduced his nascent poetic voice to the British literary scene. From a young age, he held a deep admiration for poets such as Thomas Gray and William Collins, often writing verses in imitation of their styles.

4.2. Major Poetic Works

In 1816, Hunt published his significant poem Story of Rimini. This work was inspired by the tragic episode of Francesca da Rimini, as recounted in Dante's Inferno. Despite its tragic source material, Story of Rimini presented an optimistic narrative. In 1818, Hunt released Foliage, a collection of poems, followed in 1819 by Hero and Leander and Bacchus and Ariadne. In the same year, he reissued The Story of Rimini and The Descent of Liberty under the collective title of Poetical Works. Some of Hunt's most enduring and popular poems include "Jenny kiss'd Me", "Abou Ben Adhem" (1834), and "A Night-Rain in Summer". His 1835 work, Captain Sword and Captain Pen, a spirited contrast between the victories of peace and war, is also considered among his best poems.

4.3. Poetic Style and Influences

Hunt's poetic style was distinctly influenced by the verse of Geoffrey Chaucer, as adapted into Modern English by John Dryden. This preference stood in contrast to the epigrammatic couplets favored by poets like Alexander Pope. While his work often featured narrative and lyricism, his characteristic flippancy and familiarity, which sometimes bordered on the ludicrous, occasionally made him a target for ridicule and parody.

5. Friendships and Literary Circles

Leigh Hunt was a central figure in the literary landscape of his time, fostering significant friendships and influencing prominent literary groups.

5.1. The Hunt Circle

Hunt was at the core of a vibrant group of intellectuals and artists based in Hampstead, known as the "Hunt circle." This influential group included notable figures such as William Hazlitt, Charles Lamb, Bryan Procter, Benjamin Haydon, Charles Cowden Clarke, C. W. Dilke, Walter Coulson, and John Hamilton Reynolds. Their gatherings fostered a collaborative and intellectually stimulating environment that shaped much of the literary discourse of the era.

5.2. The Cockney School

The literary group associated with Hunt, particularly those centered around him in Hampstead, was pejoratively labeled the "Cockney School" by established literary circles. This term was used to criticize their perceived lack of classical education, their urban backgrounds, and their unconventional poetic styles and themes.

5.3. Relationships with Keats and Shelley

Hunt maintained close and influential friendships with both John Keats and Percy Bysshe Shelley. Shelley provided significant financial assistance that helped save Hunt from ruin. In return, Hunt offered crucial support to Shelley during his personal and family difficulties and publicly defended him in The Examiner. Hunt was instrumental in introducing Keats to Shelley, and he wrote a very generous appreciation of Keats in The Indicator. However, Keats later reportedly felt that Hunt's example as a poet had, in some respects, been detrimental to his own development.

5.4. Other Literary Contemporaries

Hunt's network extended to other notable figures of his time, including Lord Byron and Thomas Moore. His imprisonment for libel attracted visits from these prominent individuals, as well as from Lord Henry Brougham and Charles Lamb, highlighting the social dynamics and intellectual connections within the literary scene.

6. Key Life Events and Experiences

Leigh Hunt's life was marked by significant events that profoundly impacted his career and public perception, including his notable imprisonment and influential travels.

6.1. Imprisonment

In 1813, Leigh Hunt was convicted and sentenced to two years in prison for libel against the Prince Regent George. The charge stemmed from an article in The Examiner that described the Prince Regent's physique as "corpulent." Hunt served his sentence at the Surrey County Gaol. Despite the confinement, his imprisonment was characterized by certain luxuries and access to friends and family. Notable visitors included Lord Byron, Thomas Moore, Lord Henry Brougham, and Charles Lamb. Lamb famously described Hunt's decorated cell as something "not found outside a fairy tale." The stoicism with which Hunt endured his imprisonment garnered widespread public attention and sympathy. When Jeremy Bentham visited him, he found Hunt engaged in a game of battledore.

6.2. Trip to Italy

Following Shelley's departure for Italy in 1818, Hunt faced increasing financial difficulties, compounded by declining health for both himself and his wife, Marianne. These challenges forced him to discontinue The Indicator (1819-1821), a period he described as having "almost died over the last numbers." Shelley proposed that Hunt join him and Byron in Italy to establish a new quarterly magazine, which would allow them to publish liberal opinions without the repression faced from the British government. Byron's alleged motive for this proposal was to gain more influence over The Examiner with Hunt out of England, though Byron soon discovered Hunt's diminished interest in the publication.

Hunt departed England for Italy in November 1821, but his journey was plagued by storms, sickness, and various misadventures, delaying his arrival until 1 July 1822. The arduous voyage was compared by Thomas Love Peacock to that of Ulysses in Homer's Odyssey. Tragically, just one week after Hunt arrived in Italy, Shelley died. This left Hunt largely dependent upon Byron, who, however, showed little interest in supporting Hunt and his family. Byron's friends also openly scorned Hunt. The collaborative magazine, The Liberal, managed to publish four quarterly numbers, featuring memorable contributions such as Byron's "Vision of Judgment" and Shelley's translations from Faust. In 1823, Byron left Italy for Greece, effectively abandoning the quarterly. Hunt, choosing to remain in Genoa, enjoyed the Italian climate and culture, staying until 1825. During this period, he produced Ultra-Crepidarius: a Satire on William Gifford (1823) and his 1825 translation of Francesco Redi's Bacco in Toscana.

7. Personal Life and Family

Leigh Hunt's personal life revolved around his marriage and a large family, though he maintained a degree of reticence about these matters in his public writings.

7.1. Marriage and Children

In 1809, Leigh Hunt married Marianne Kent, the daughter of Thomas and Ann Kent. Over the course of their 20-year marriage, the couple had ten children:

- Thornton Leigh (1810-1873)

- John Horatio Leigh (1812-1846)

- Mary Florimel Leigh (1813-1849)

- Swinburne Percy Leigh (1816-1827)

- Percy Bysshe Shelley Leigh (1817-1899)

- Henry Sylvan Leigh (1819-1876)

- Vincent Leigh (1823-1852)

- Julia Trelawney Leigh (1826-1872)

- Jacyntha Leigh (1828-1914)

- Arabella Leigh (1829-1830)

Marianne Hunt suffered from poor health for most of her life and passed away on 26 January 1857, at the age of 69.

7.2. Family Connections

Despite his extensive family, Leigh Hunt made relatively little mention of his personal life or family in his autobiography. His sister-in-law, Elizabeth Kent, Marianne's sister, played a significant role in his life, serving as his amanuensis.

8. Later Life and Legacy

Leigh Hunt's later years were characterized by continued literary output, persistent financial struggles, and a complex legacy, including his notable depiction in fiction.

8.1. Later Writings and Publications

In 1825, a lawsuit involving one of his brothers necessitated Hunt's return to England. In 1828, he published Lord Byron and some of his Contemporaries, a work intended to correct what Hunt perceived as an inaccurate public image of Byron. This publication, however, shocked the public, who viewed it as an act of ingratitude towards Byron, to whom Hunt had been indebted. Hunt particularly suffered under the scathing satire of Thomas Moore in response to this work.

During the 1830s, Hunt also wrote for the Edinburgh Review. In 1832, he published a collected edition of his poems by subscription, which notably included many of his former opponents among the subscribers. Also in 1832, Hunt privately circulated Christianism, a work later published in 1853 as The Religion of the Heart. A copy sent to Thomas Carlyle secured their friendship, leading Hunt to move next door to Carlyle in Cheyne Row in 1833. His romance novel, Sir Ralph Esher, set during the time of Charles II, achieved success.

In 1840, Hunt's play Legend of Florence enjoyed a successful run at Covent Garden, providing him with much-needed financial relief. Lover's Amazements, a comedy, was performed several years later and printed in his Journal (1850-1851), while other plays remained in manuscript. Also in 1840, Hunt contributed introductory notices to the works of Richard Brinsley Sheridan and to Edward Moxon's edition of the works of William Wycherley, William Congreve, John Vanbrugh, and George Farquhar. A narrative poem, The Palfrey, was published in 1842.

With his finances somewhat improved in his final years, Hunt published the companion books Imagination and Fancy (1844) and Wit and Humour (1846). These two volumes, comprising selections from English poets, showcased his refined and discerning critical tastes. He also published A Jar of Honey from Mount Hybla (1848), a book focusing on the pastoral poetry of Sicily. The Town (2 vols., 1848) and Men, Women and Books (2 vols., 1847) partly consisted of previously published material. The Old Court Suburb (2 vols., 1855), edited by A. Dobson in 2002, offered a sketch of Kensington, where Hunt resided for a considerable period. In 1850, Hunt published his comprehensive Autobiography (3 vols.), which has been described as a naive and affected yet accurate self-portrait. He also published A Book for a Corner (2 vols.) in 1849, and Table Talk appeared in 1851. In 1855, he collected his narrative poems, both original and translated, under the title Stories in Verse.

8.2. Financial Difficulties and Support

Throughout his later years, Hunt continued to grapple with persistent poverty and ill health. Despite working tirelessly, many of his ventures met with failure. Two journalistic undertakings, the Tatler (1830-1832), a daily devoted to literary and dramatic criticism, and the London Journal (1834-1835), both failed, even though the latter contained some of his finest writing. His editorship (1837-1838) of the Monthly Repository was also unsuccessful. Despite these struggles, he received some financial support in his later life. In 1844, Mary Shelley and her son, upon inheriting family estates, settled an annuity of 120 GBP upon Hunt. In 1847, Lord John Russell further established a pension of 200 GBP for Hunt.

8.3. Depiction by Charles Dickens

In a letter dated 25 September 1853, Charles Dickens confirmed that Leigh Hunt had served as the inspiration for the character of Harold Skimpole in his novel Bleak House. Dickens stated, "I suppose he is the most exact portrait that was ever painted in words! ... It is an absolute reproduction of a real man." A contemporary critic corroborated this, commenting, "I recognized Skimpole instantaneously; ... and so did every person whom I talked with about it who had ever had Leigh Hunt's acquaintance." However, G. K. Chesterton offered an alternative perspective, suggesting that Dickens "May never once have had the unfriendly thought, 'Suppose Hunt behaved like a rascal!'; he may have only had the fanciful thought, 'Suppose a rascal behaved like Hunt!'"

8.4. Death and Memorials

Leigh Hunt died in Putney, London, on 28 August 1859, at the age of 74. He was laid to rest at Kensal Green Cemetery. In September 1966, Christ's Hospital, his former school, named one of its houses in his memory. Additionally, a residential street in his birthplace of Southgate is named Leigh Hunt Drive in his honor.

9. Other Works

Leigh Hunt's literary output extended to various translations, compilations, and works edited by others, showcasing the breadth of his engagement with literature:

- Amyntas, A Tale of the Woods (1820), a translation of Tasso's Aminta

- The Seer, or Common-Places refreshed (2 parts, 1840-1841)

- Three of the Canterbury Tales in The Poems of Geoffrey Chaucer modernized (1841)

- Stories from the Italian Poets (1846)

- Compilations such as One Hundred Romances of Real Life (1843)

- Selections from Beaumont and Fletcher (1855)

- The Book of the Sonnet (Boston, 1867), co-edited with S. Adams Lee.

His Poetical Works (2 vols.), revised by himself and edited by Lee, were printed in Boston in 1857. An edition (London and New York) by his son, Thornton Hunt, appeared in 1860. Volumes of selections include Essays (1887), edited by A. Symons; Leigh Hunt as Poet and Essayist (1889), edited by C. Kent; and Essays and Poems (1891), edited by R. B. Johnson for the "Temple Library." Elizabeth Kent also incorporated many of Hunt's suggestions into her anonymously published Flora Domestica, Or, The Portable Flower-garden: with Directions for the Treatment of Plants in Pots and Illustrations From the Works of the Poets (1823). Hunt's Autobiography was revised shortly before his death and edited (1859) by Thornton Hunt, who also arranged his Correspondence (2 vols., 1862). Additional letters were printed by the Cowden Clarkes in their Recollections of Writers (1878). The Autobiography was later edited (2 vols., 1903) with a full bibliographical note by Roger Ingpen. A bibliography of Hunt's works was compiled by Alexander Ireland (List of the Writings of William Hazlitt and Leigh Hunt, 1868).

10. Assessment and Influence

Leigh Hunt's contributions to English literature are multifaceted, encompassing his roles as a critic, essayist, and poet. As a journalist, he was a key figure in the development of the periodical press, using The Examiner to champion radical political and social ideas, thereby influencing public discourse and holding power accountable. His willingness to challenge authority, even at the cost of imprisonment, underscored his commitment to independent thought and a free press, reflecting a perspective that, while controversial in his time, aligns with the principles of democratic progress.

His literary criticism was noted for its refined and discriminating taste, as evidenced in works like Imagination and Fancy and Wit and Humour. As a poet, he introduced a distinctive style, drawing on influences from Chaucer and Dryden, and contributed to the Romantic movement with narrative and lyrical works. Despite criticisms regarding his occasional flippancy, his accessible language and optimistic narratives offered a contrast to some of his contemporaries.

Hunt's role as a literary connector was profound; he fostered the "Hunt circle" and introduced a new generation of poets, including Keats and Shelley, to a wider audience, facilitating their entry into the literary world and influencing their early development. His personal struggles with poverty and health, often reflected in his later writings, provide a poignant insight into the challenges faced by writers of his era. While his depiction in Dickens' Bleak House as Harold Skimpole presented a complex and debated aspect of his public image, it also cemented his place in literary history. Ultimately, Leigh Hunt's legacy is that of a versatile and influential figure who, through his critical acumen, journalistic fervor, and poetic voice, played a significant role in shaping the literary and intellectual landscape of 19th-century England.