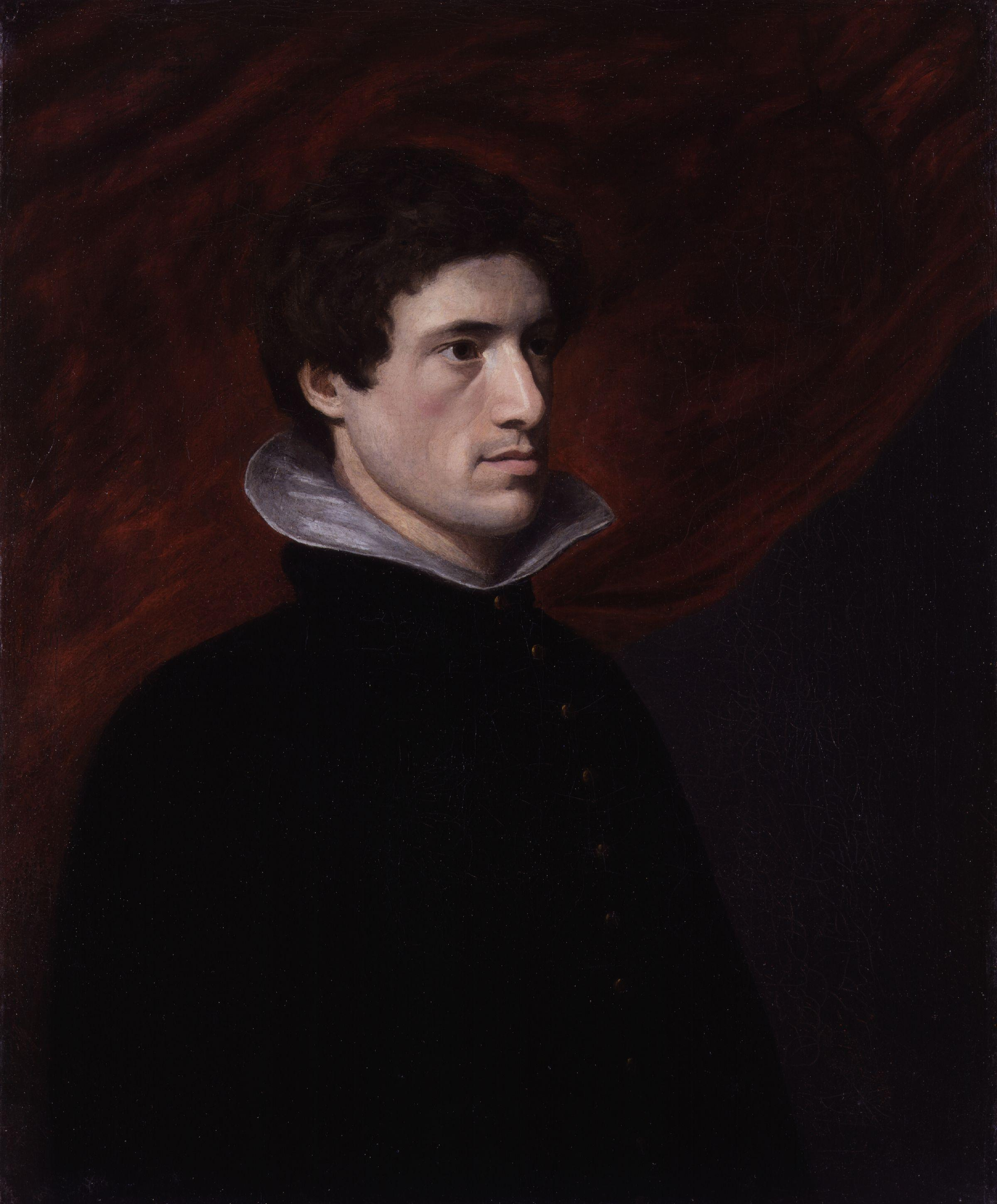

1. Life

Charles Lamb's life journey was deeply shaped by his family, his long career, and the personal tragedies he endured, particularly his unwavering dedication to his sister, Mary.

1.1. Youth and Schooling

Charles Lamb was born on 10 February 1775 in London, England. His father, John Lamb (c. 1725-1799), worked as a lawyer's clerk for Samuel Salt, a barrister who resided in the Inner Temple, a legal district in London. Charles spent his youth in Crown Office Row within the Inner Temple, where he was born. He later drew a portrait of his father in his essay "Elia on the Old Benchers," calling him Lovel. Charles had an elder brother, also named John, and a sister, Mary; four other siblings did not survive infancy. Mary, being eleven years his senior, was likely his closest playmate during childhood. He was also cared for by his paternal aunt, Hetty, of whom Charles spoke fondly, despite some tension between her and his mother.

Some of Lamb's most cherished childhood memories were spent with his maternal grandmother, Mrs. Field, who served the Plumer family at their large country house, Blakesware, near Widford, Hertfordshire. Charles enjoyed free rein of the estate during his visits, a period he vividly depicted in his Elia essay Blakesmoor in H-shire. Mary taught him to read at a very early age, and he became a voracious reader. It is believed he contracted smallpox in his early years, leading to a prolonged period of recovery. Following this, he received lessons from Mrs. Reynolds, a woman living in the Temple, with whom he maintained a lifelong relationship. Around 1781, Charles briefly studied at the Academy of William Bird.

In October 1782, Lamb was enrolled in Christ's Hospital, a charity boarding school chartered by King Edward VI in 1553. His experiences there are well-documented in his own essays, as well as in The Autobiography of Leigh Hunt and the Biographia Literaria by Samuel Taylor Coleridge, with whom Lamb formed a lifelong friendship at the school. Despite the school's reputation for brutality, Lamb fared well, partly because his home was nearby, allowing him frequent visits. The school's headmaster from 1778 to 1799, Reverend James Boyer, was known for his unpredictable temper. However, Lamb largely avoided this harshness due to his amiable personality and the influence of his father's employer, Samuel Salt, who was a governor of the institution and Lamb's sponsor.

Lamb's stutter, which he described as an "inconquerable impediment," prevented him from achieving "Grecian status" at Christ's Hospital, thereby disqualifying him from a clerical career. Unlike Coleridge and other academically gifted boys who went on to Cambridge, Lamb left school at the age of fourteen and was compelled to seek a more practical profession. He briefly worked for Joseph Paice, a London merchant, and then for 23 weeks at the Examiner's Office of the South Sea House until 8 February 1792. The company's subsequent collapse into a pyramid scheme after his departure was later humorously contrasted with its former prosperity in his first Elia essay. On 5 April 1792, following the financial ruin of his family after his father's employer's death, he began working in the Accountant's Office for the British East India Company.

1.2. East India Company Service

Charles Lamb continued his employment at the British East India Company for 25 years, working in the Accountant's Office. This stable position provided him with financial security until his retirement with a pension, which he humorously referred to as "superannuation" in the title of one of his essays. His long service at the company allowed him to support his family, particularly his sister Mary, throughout his life.

1.3. Family Tragedy and Personal Life

Charles Lamb's life was profoundly marked by personal tragedy and his unwavering dedication to his family, particularly his sister Mary, who suffered from severe mental illness.

1.3.1. Mary Lamb and the Matricide

Both Charles and his sister Mary experienced periods of mental illness. Charles himself confessed in a letter that he spent six weeks in a mental facility in Hoxton during 1795. Mary's illness, however, was more severe and led to a tragic incident on 22 September 1796. While preparing dinner, Mary became agitated and roughly pushed her apprentice out of the way. When her mother, Elizabeth, began admonishing her for this, Mary suffered a severe mental breakdown. Overwhelmed by "extreme nervous misery by attention to needlework by day and to her mother at night," she seized the kitchen knife she was holding and fatally stabbed her mother in the heart. Charles arrived shortly after the murder and managed to disarm his sister.

Later that evening, Charles, with the help of a doctor friend, found a place for Mary in a private mental facility called Fisher House in Islington. Despite the incident being reported in the media, Charles wrote a letter to Samuel Taylor Coleridge, informing him of the "terrible calamities" that had befallen their family. He recounted that his "poor dear dearest sister in a fit of insanity has been the death of her own mother," and that he arrived just in time to snatch the knife from her grasp. He expressed that Mary was in a madhouse and he feared she would have to be moved to a hospital. Charles affirmed that he had retained his senses and judgment, and was left to care for his slightly wounded father and his aunt. He requested a "religious letter" from Coleridge, emphasizing that "the former things are passed away," and he had "something more to do that [than] to feel."

Charles took full responsibility for Mary, rejecting his brother John's suggestion to commit her to a public lunatic asylum. He used a significant portion of his modest income to keep his beloved sister in the private "madhouse." With the assistance of friends, Lamb successfully secured Mary's release from what would otherwise have been lifelong imprisonment. Although there was no specific legal status of "insanity" at the time, the jury returned a verdict of "lunacy," which freed her from the guilt of willful murder, on the condition that Charles personally guaranteed her safekeeping.

The death of John Lamb, their father, in 1799, was somewhat of a relief to Charles, as his father had been mentally incapacitated for several years following a stroke. His father's passing also allowed Mary to return to live with Charles in Pentonville, and in 1800, they established a shared home at Mitre Court Buildings in the Temple, where they resided until 1809. In 1800, Mary's illness recurred, and Charles again had to take her to the asylum. During this period, he wrote to Coleridge, admitting to feeling melancholic and lonely, even stating, "I almost wish that Mary were dead."

Despite these recurring challenges, Mary eventually returned home, and both she and Charles enjoyed an active and rich social life. Their London residence became a weekly salon, attracting many of the most distinguished theatrical and literary figures of the era. This tradition was later honored by the formation of The Lambs club in London in 1869, and its New York counterpart in 1874, founded by the actor Henry James Montague.

1.3.2. Romantic Relationships and Bachelorhood

In 1792, while caring for his grandmother, Mary Field, in Hertfordshire, Charles Lamb fell in love with a young woman named Ann Simmons. Although no direct correspondence exists from their relationship, Lamb's writings suggest he spent years pursuing her. She is believed to be the inspiration for Rosamund Gray in his novella of the same name, and appears as "Alice M" in several of his Elia essays, including "Dream Children" and "New Year's Eve." These essays speak of his long, ultimately unsuccessful pursuit, which he later called his "great disappointment" after Miss Simmons married a silversmith.

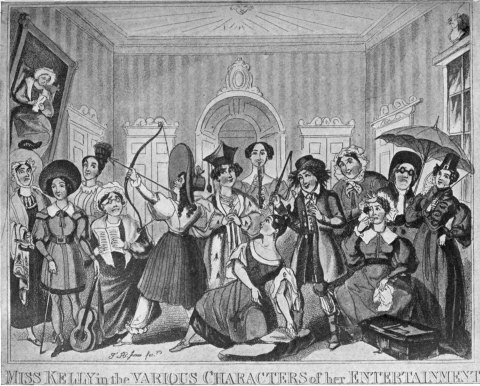

On 20 July 1819, at the age of 44, Lamb, who had never married due to his family commitments, fell in love with Fanny Kelly, an actress at Covent Garden. He not only wrote her a sonnet but also proposed marriage. However, she refused his proposal, and Charles Lamb remained a bachelor throughout his life, his dedication to Mary being a primary factor in his decision.

His close friend, Samuel Taylor Coleridge, with whom he had attended school, remained perhaps his oldest and closest companion. On his deathbed, Coleridge arranged for a mourning ring to be sent to Lamb and his sister. In 1834, Samuel Coleridge died, and due to the private nature of the funeral, Lamb was unable to attend. He instead wrote a letter of condolence to Rev. James Gilman, Coleridge's physician and close friend.

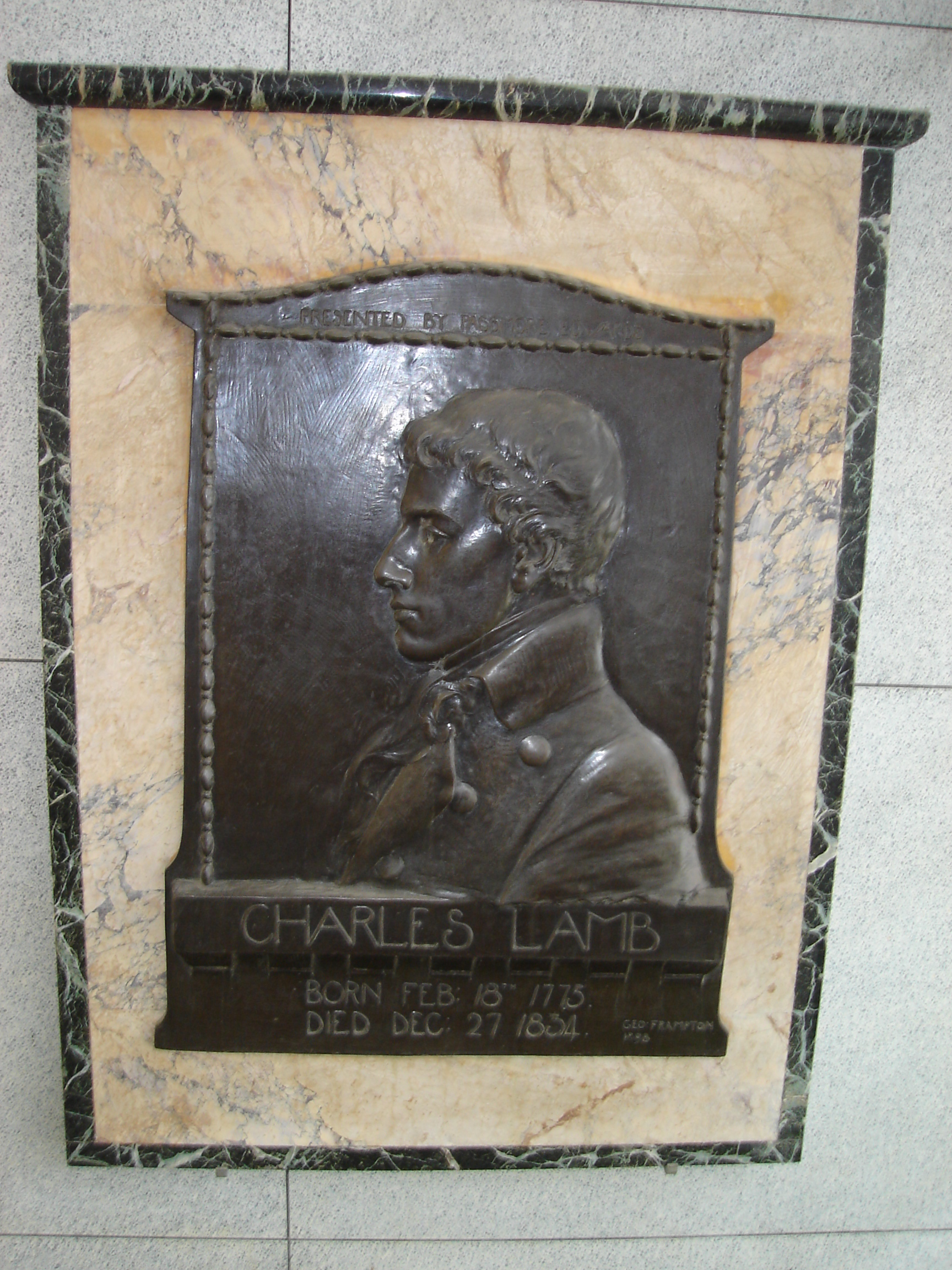

On 27 December 1834, Charles Lamb died at the age of 59 from a streptococcal infection, erysipelas, which he contracted from a minor graze on his face after slipping in the street. From 1833 until their deaths, Charles and Mary resided at Bay Cottage, Church Street, Edmonton, north of London. Lamb is buried in All Saints' Churchyard in Edmonton, alongside his sister, who survived him by more than a decade.

2. Literary Career and Works

Charles Lamb's literary career spanned several genres, from early poetry and prose to his celebrated essays and significant collaborations, leaving a lasting impact on English literature.

2.1. Early Poetry and Prose

Lamb's first published work appeared in 1796, when four of his sonnets, credited to "Mr Charles Lamb of the India House," were included in Samuel Taylor Coleridge's Poems on Various Subjects. These early sonnets were notably influenced by the works of Robert Burns and the sonnets of William Lisle Bowles. While his early poems garnered little attention and are seldom read today, Lamb himself later recognized his greater talent as a prose stylist. As early as 1815, William Wordsworth, a celebrated poet of the time, observed that Lamb "writes prose exquisitely," a remark made five years before Lamb began writing the Essays of Elia for which he is now most famous.

Lamb's contributions to the second edition of Coleridge's Poems on Various Subjects in 1797, which included The Tomb of Douglas and A Vision of Repentance, demonstrated significant growth in his poetic abilities. Although a temporary disagreement with Coleridge led to his poems being excluded from a planned third edition (which never materialized, as Coleridge's next major work was the influential Lyrical Ballads with Wordsworth), Lamb went on to publish a book titled Blank Verse in 1798 with Charles Lloyd. It was during this period that Lamb wrote his most famous poem, "The Old Familiar Faces". This poem, like much of Lamb's poetry, is overtly sentimental, a quality that has contributed to its enduring remembrance and widespread inclusion in anthologies of British and Romantic period poetry. The original opening verse of "The Old Familiar Faces," concerning his mother's tragic death, was later removed by Lamb from the 1818 edition of his Collected Works:

"I had a mother, but she died, and left me,

Died prematurely in a day of horrors -

All, all are gone, the old familiar faces."

The blank verse poems in Blank Verse also expressed the spiritual struggles Lamb experienced after his mother's death, as he reflected on life and death, lamented the passage of time, and revealed deepening religious doubts.

In the final years of the 18th century, Lamb ventured into prose with his novella A Tale of Rosamund Gray, and Old Blind Margaret. The story, which features a young girl whose character is thought to be based on Ann Simmons, an early romantic interest of Lamb's, was not particularly successful in terms of plot. However, it was well-regarded by his contemporaries, with Percy Bysshe Shelley remarking, "what a lovely thing is Rosamund Gray! How much knowledge of the sweetest part of our nature in it!"

2.2. Essays of Elia

Lamb's most celebrated work, the Essays of Elia, first appeared in collected form in 1823, with a further collection, The Last Essays of Elia, published in 1833, shortly before his death. "Elia" was the pen name Lamb adopted for his contributions to The London Magazine.

The essays are characterized by a distinctive personal style, often described as contrived yet accurate in portraying the persona of Elia. They are rich with both humor and pathos, exploring themes such as old friends, childhood memories, and the experience of aging. These writings reflect Lamb's playful and imaginative character. Despite their seemingly lighthearted style, the Essays of Elia embody the spirit of Romanticism, akin to the works of Coleridge and Wordsworth, while Elia's fascination with urban topics also draws parallels to the writings of Charles Dickens.

Lamb's gradual refinement of the essay form began as early as 1811, in a series of open letters published in Leigh Hunt's Reflector. One of these early essays, "The Londoner," famously satirized the contemporary fascination with nature and the countryside. In another notable Reflector essay from 1811, Lamb asserted that William Hogarth's images were like "books," filled with "the teeming, fruitful, suggestive meaning of words. Other pictures we look at; his pictures we read." He continued to hone his craft, experimenting with various essayistic voices and personae, for much of the next quarter-century.

The Essays of Elia faced criticism from Robert Southey in the Quarterly Review in January 1823, in an article titled "The Progress of Infidelity," which accused Lamb of being irreligious. Lamb was deeply offended by this review and initially hesitated to respond, as he admired Southey. However, he later felt compelled to write a letter, "Elia to Southey," published in The London Magazine in October 1823. In this letter, Lamb complained about the accusation, emphasizing that his status as a Dissenter did not make him an irreligious man. He clarified, "Rightly taken, Sir, that Paper was not against Graces, but Want of Grace; not against the ceremony, but the carelessness and slovenliness so often observed in the performance of it. . . You have never ridiculed, I believe, what you thought to be religion, but you are always girding at what some pious, but perhaps mistaken folks, think to be so."

2.3. Tales from Shakespeare

In the early 19th century, Charles Lamb embarked on a highly productive literary collaboration with his sister Mary. Together, they authored at least three books for William Godwin's Juvenile Library. The most successful of these was Tales From Shakespeare, published in 1807, which became a bestseller and has since been published in countless editions. The book contains artful prose summaries of twenty of Shakespeare's most beloved plays, adapted for a young audience. According to Charles Lamb, he primarily focused on adapting Shakespeare's tragedies, while Mary concentrated on the comedies.

2.4. Literary Criticism and Antiquarianism

Charles Lamb was also a notable literary critic and antiquarian, whose insights significantly contributed to the understanding and appreciation of older English literature. His essay "On the Tragedies of Shakespeare Considered with Reference to their Fitness for Stage Representation," originally published in the Reflector in 1811, was prompted by his viewing of the David Garrick memorial in Westminster Abbey. This essay is often regarded as a definitive Romantic dismissal of theatrical performance, as Lamb argued that Shakespeare's plays should be read rather than performed to protect them from commercialization and celebrity culture. While criticizing contemporary stage practices, the essay also offers a complex reflection on the imaginative representation of Shakespearean dramas. Lamb believed that Shakespeare's works were best experienced through a "complex cognitive process" that relies on "imaginative elements... suggestively elicited by words," allowing the reader to mentally materialize Shakespeare's conceptions in a dreamlike state of consciousness.

Lamb also played a crucial role in reintroducing the works of Shakespeare's contemporaries to the public. In 1808, he compiled Specimens of the English Dramatic Poets Who Lived About the Time of Shakespeare, a collection of extracts from old dramatists, which included his own critical "characters" of these writers. This work further solidified his reputation as an antiquarian and added to the growing body of significant literary criticism from his pen, primarily focusing on Shakespeare and his contemporaries. His deep immersion in 17th-century authors such as Robert Burton and Sir Thomas Browne profoundly influenced his own writing style, imbuing it with a distinct flavor.

His friend, the essayist William Hazlitt, characterized Lamb as someone who "does not march boldly along with the crowd .... He prefers bye-ways to highways." Hazlitt noted that while others flocked to festive shows, Elia would "stand on one side to look over an old book-stall, or stroll down some deserted pathway in search of a pensive description over a tottering doorway, or some quaint device in architecture, illustrative of embryo art and ancient manners. Mr. Lamb has the very soul of an antiquarian ...."

2.5. Other Notable Works

Beyond his most famous essays and collaborations, Charles Lamb produced several other significant works throughout his career. His verse drama, John Woodvil, was published in 1802. In 1807, his farce, Mr H, was performed at Drury Lane but was met with widespread booing. He also wrote The Adventures of Ulysses, published in 1808, which retold the epic tale for a younger audience. Another notable work was The Pawnbroker's Daughter, published in 1825.

3. Literary Circle and Influences

Charles Lamb's literary output and intellectual perspective were deeply influenced by his close relationships with his contemporaries and his unique literary tastes.

3.1. Friends and Contemporaries

Charles Lamb's literary circle was a vibrant hub of intellectual exchange, centered around his London quarters, which became a weekly salon for many of the day's most outstanding theatrical and literary figures. His friendship with Samuel Taylor Coleridge, forged during their school days at Christ's Hospital, was perhaps his closest and certainly his longest. Coleridge was instrumental in fostering Lamb's early interest in poetry, and on his deathbed, he arranged for a mourning ring to be sent to Lamb and his sister as a token of their enduring bond.

In 1797, during a short summer holiday with Coleridge at Nether Stowey, Lamb met William Wordsworth and Dorothy Wordsworth, initiating a lifelong friendship with William. In London, Lamb became acquainted with a group of young writers who advocated for political reform, including Percy Bysshe Shelley, William Hazlitt, Leigh Hunt, and William Hone. These connections not only provided him with intellectual stimulation but also influenced his perspectives and provided material for his essays.

3.2. Literary Tastes and Preferences

Charles Lamb possessed distinct literary tastes and intellectual preferences, as observed by his contemporaries, notably William Hazlitt. Hazlitt characterized Lamb as someone who did not conform to the "spirit of the age" but rather went against it, preferring "bye-ways" to "highways." He was described as modest and delicate, free from vanity or self-assertion, and drawn to hidden, distant, and intrinsically valuable things. Lamb was noted for his aversion to new faces, books, buildings, and customs.

Regarding his reading habits, Lamb was well-versed in authors like Tobias Smollett and Henry Fielding. However, he showed less interest in figures such as Junius or Edward Gibbon. Instead, he gravitated towards specialized classics, including Robert Burton's The Anatomy of Melancholy, the works of Sir Thomas Browne, Thomas Fuller's Worthies, and John Bunyan's The Holy War. He held a profound reverence for William Shakespeare and John Milton. Hazlitt also noted Lamb's limited interest in German and French literature and economics, and that his knowledge of theological disputes was largely derived from books. Beyond literature, Lamb was a discerning connoisseur of paintings and prints, holding particular admiration for the works of William Hogarth and Leonardo da Vinci.

4. Religious Views

Christianity played a significant role in Charles Lamb's personal life. Although he was not a conventional churchman, he "sought consolation in religion," as evidenced in his letters to Samuel Taylor Coleridge and Bernard Barton. In these letters, he described the New Testament as his "best guide" for life and recalled reading the Psalms for hours without tiring. Other writings also confirm his Christian beliefs, with commentators noting his "great, and indeed infinite reverence, nevertheless, for Christ."

Like his friend Coleridge, Lamb was sympathetic to Priestleyan Unitarianism and identified as a Dissenter. Coleridge himself affirmed that Lamb's "faith in Jesus ha[d] been preserved" even after the profound family tragedy he endured. William Wordsworth also described him as a firm Christian in his poem "Written After the Death of Charles Lamb." Alfred Ainger, in his work Charles Lamb, suggested that Lamb's religion had become "an habit."

Lamb's religious faith is explicitly expressed in several of his poems, including "On The Lord's Prayer," "A Vision of Repentance," "The Young Catechist," "Composed at Midnight," "Suffer Little Children, and Forbid Them Not to Come Unto Me," "Written a Twelvemonth After the Events," "Charity," "Sonnet to a Friend," and "David." Conversely, his poem "Living Without God in the World" has been characterized as a "poetic attack" on unbelief, in which Lamb conveys his disgust at atheism, attributing it to pride. While the Indonesian source suggests that some of Lamb's blank verse poems expressed "deepening religious doubts" after his mother's death, these reflections appear to be part of a broader spiritual struggle that ultimately led him to seek consolation and reaffirm his Christian convictions.

5. Legacy and Critical Reception

Charles Lamb's unique literary style and personal charm have ensured a lasting, albeit niche, place in English literature, influencing subsequent writers and inspiring various cultural tributes.

5.1. Enduring Popularity and Cult Following

Charles Lamb's works have consistently maintained a small but dedicated following, as demonstrated by the long-running Charles Lamb Bulletin. Due to his distinctive, often quirky and idiosyncratic style, he has been more of a "cult favourite" than an author with widespread popular or mainstream scholarly appeal. The American essayist Anne Fadiman has lamented that Lamb is not widely read in modern times, noting, "I do not understand why so few other readers are clamoring for his company... [He] is kept alive largely through the tenuous resuscitations of university English departments." Despite this, his value has been recognized in various cultural contexts; for instance, in Japan, Fukuhara Rintarō's biography of Charles Lamb received the Yomiuri Literary Prize, significantly popularizing Lamb's work in the post-war Japanese reading public.

5.2. Honors and Memorials

Charles Lamb has been honored in several ways. Two of the houses at Christ's Hospital (Lamb A and Lamb B), his former school, are named in his honor. He is also recognized at The Latymer School, a grammar school in Edmonton, where he lived for a time, with one of its six houses bearing his name. Christ's Hospital also awards "The Lamb Prize for Independent Study" annually on its speech day.

In the arts, Sir Edward Elgar composed an orchestral work titled Dream Children, directly inspired by Lamb's essay of the same title. A famous quotation from Lamb, "Lawyers, I suppose, were children once," serves as the epigraph to Harper Lee's acclaimed novel To Kill a Mockingbird. In London, a pub in Islington is named "The Charles Lamb" in his honor. The Lambs Club, founded in New York by Henry James Montague, was named after the renowned literary salon hosted by Charles and his sister Mary Lamb. Furthermore, Charles Lamb plays a significant role in the plot of Mary Ann Shaffer and Annie Barrows's novel, The Guernsey Literary and Potato Peel Pie Society.

5.3. Critical Assessment and Influence

Lamb's literary achievements have been critically evaluated for their unique style and lasting impact. His essays, particularly the Essays of Elia, are lauded for their blend of humor, pathos, and distinctive personal voice, which set a new standard for the essay form. His work as a literary critic, especially his Specimens of the English Dramatic Poets, contributed significantly to the revival of interest in older English dramatists. The detailed observations of his contemporary, William Hazlitt, highlight Lamb's preference for the subtle and overlooked aspects of life and literature, underscoring his "soul of an antiquarian." While his poetry is less celebrated, "The Old Familiar Faces" remains a notable exception for its enduring sentimentality. Lamb's influence can be seen in subsequent writers who adopted a more personal and reflective essayistic style.

6. Selected Works

- Blank Verse, poems (1798)

- A Tale of Rosamund Gray, and Old Blind Margaret (1798)

- John Woodvil, verse drama (1802)

- Tales from Shakespeare (1807)

- The Adventures of Ulysses (1808)

- Specimens of English Dramatic Poets who Lived About the Time of Shakespeare (1808)

- On the Tragedies of Shakespeare (1811)

- Witches and Other Night Fears (1821)

- Essays of Elia (1823)

- The Pawnbroker's Daughter (1825)

- The Last Essays of Elia (1833)

- Eliana (1867)