1. Life and Resurrection

Lazarus of Bethany is a central figure in the Gospel of John, known for his close relationship with Jesus and the pivotal miracle of his resurrection.

1.1. Background and Relationship with Jesus

Lazarus resided in the town of Bethany, which is located near Jerusalem, approximately 2 mile away. He was the brother of Mary and Martha, and all three were known to be close friends of Jesus. Jesus frequently visited their home, as noted in the Gospels. The biblical narrative begins when Lazarus falls ill, prompting his sisters, Mary and Martha, to send word to Jesus, stating, "Lord, he whom thou lovest, is sick." Upon hearing the news, Jesus declared that the sickness "will not end in death. No, it is for God's glory so that God's Son may be glorified through it." Despite his affection for Lazarus and his sisters, Jesus intentionally remained where he was for two more days before beginning his journey to Bethany. He informed his disciples, "Our friend Lazarus is asleep, but I am going to awaken him." When the disciples misunderstood, Jesus clarified, "Lazarus is dead, and for your sake I am glad I was not there, so that you may believe. Let us go to him."

1.2. Biblical Narrative of the Raising

Upon Jesus's arrival in Bethany, he found that Lazarus had already been in his tomb for four days. Many Jews had come to console Martha and Mary over their brother's death. Martha met Jesus first, lamenting, "Lord, if you had been here, my brother would not have died." Jesus responded with the profound declaration, "I am the resurrection, and the life; he that believeth in me, though he were dead, yet shall he live: And whosoever liveth and believeth in me shall never die." Martha affirmed her faith, stating, "Yes, Lord. I believe that you are the Messiah, the Son of God, who has to come into the world."

When Mary arrived, she knelt at Jesus's feet and echoed her sister's words, "Lord, if you had been here, my brother would not have died." Witnessing Mary and the accompanying Jews weeping, Jesus was deeply moved and troubled. He asked, "Where have ye laid him?" They replied, "Lord, come and see." At this moment, "Jesus wept."

Jesus then proceeded to the tomb, which was a cave sealed with a stone. He commanded, "Take ye away the stone!" Martha interjected, warning that there would be a smell, as Lazarus had been dead for four days. Jesus countered, "Did I not tell you that if you believed, you would see the glory of God?" Despite her objection, the stone was rolled away from the entrance. Jesus then looked heavenward and prayed, "Father, I thank you that you have heard me. I know that you always hear me, but I said this for the benefit of the people standing here, that they may believe that you sent me." After this, Jesus cried out in a loud voice, "Lazarus, come forth!" The dead man emerged, still wrapped in his grave-cloths, with his face covered by a cloth. Jesus then instructed those present, "Loose him, and let him go."

1.3. Aftermath of the Resurrection

The narrative concludes by stating that many of the Jewish witnesses who saw this miracle believed in Jesus. However, others reported the events to the religious authorities in Jerusalem, specifically the chief priests.

The Gospel of John mentions Lazarus again in chapter 12. Six days before the Passover during which Jesus was crucified, Jesus returned to Bethany. Lazarus attended a supper hosted there, served by his sister Martha. The presence of both Jesus and Lazarus attracted a large crowd of Jews, who came not only to see Jesus but also to witness the man he had raised from the dead. The narrator explicitly states that the chief priests then conspired to kill Lazarus as well, because his resurrection was causing many people to abandon them and believe in Jesus.

The miracle of the raising of Lazarus is considered the longest coherent narrative in John, apart from the Passion of Jesus. It is viewed as the culmination of John's "signs," explaining the large crowds that sought Jesus on Palm Sunday and leading directly to the decision by Caiaphas and the Sanhedrin to plan Jesus's death. A very similar resurrection story also appears in the controversial Secret Gospel of Mark, although the young man in that account is not specifically named. Some scholars believe that the Secret Mark version represents an earlier form of the canonical story found in John.

2. Tomb of Lazarus

The traditional Tomb of Lazarus is located in the town of Bethany, known today as Al-Eizariya (meaning "place of Lazarus"), in the West Bank. This site has remained a significant place of pilgrimage for centuries.

The present-day entrance to the tomb consists of a flight of uneven rock-cut steps leading down from the street. As described in 1896, and still applicable today, there are twenty-four steps from the modern street level, which descend to a square chamber that serves as a place of prayer. From this chamber, additional steps lead to a lower chamber, traditionally believed to be the actual tomb of Lazarus.

Several Christian churches have stood on this site throughout history. The earliest mention of a church in Bethany dates to the late 4th century. Both Eusebius of Caesarea (circa 330) and the Bordeaux pilgrim mention the tomb of Lazarus. In 390, Jerome specifically referred to a church dedicated to Saint Lazarus, known as the Lazarium. This is further confirmed by the pilgrim Egeria around 410. Based on these accounts, it is believed that the first church was constructed between 333 and 390. Remnants of a mosaic floor from this 4th-century church can still be seen in the present-day gardens at the site. The Lazarium was destroyed by an earthquake in the 6th century but was subsequently replaced by a larger church, which remained intact until the Crusades era.

In 1143, King Fulk and Queen Melisende of Jerusalem acquired the existing structure and lands. They then built a large Benedictine convent dedicated to Mary and Martha near Lazarus's tomb. Following the fall of Jerusalem in 1187, the convent was abandoned and fell into ruin, with only the tomb and parts of its barrel vaulting surviving. By 1384, a simple mosque had been constructed on the site. In the 16th century, the Ottomans built the larger Al-Uzair Mosque to serve the predominantly Muslim inhabitants of the town, naming it in honor of Lazarus of Bethany, whom they revered.

Adjacent to the tomb and mosque stands the modern Roman Catholic Church of Saint Lazarus, designed by Antonio Barluzzi and constructed between 1952 and 1955 under the patronage of the Franciscan Order. This church was built upon the foundations of several much older churches. In 1965, a Greek Orthodox Church was also erected just west of the tomb.

While some scholars, as noted in the Catholic Encyclopedia of 1913, questioned whether the current village of Bethany occupied the precise site of the ancient village, the Encyclopedia's author argued against this, stating that the village likely developed around the traditional cave, which they supposed was some distance from the house of Martha and Mary. Although the identification of this particular cave as the tomb of Lazarus is considered merely possible and lacks strong intrinsic or extrinsic authority, there is a general consensus that the ancient village was located in this general area.

3. Later Traditions

Although the Bible provides no further details about Lazarus after his resurrection, various traditions in the Eastern Orthodox Church and Roman Catholic traditions offer differing accounts of his later life. He is most commonly associated with Cyprus, where he is believed to have become the first bishop of Kition (modern-day Larnaca), and with Provence, where he is said to have been the first bishop of Marseille.

3.1. Bishop of Kition (Cyprus)

According to Eastern Orthodox Church tradition, Lazarus was compelled to flee Judea after the Resurrection of Christ due to rumored plots against his life. He journeyed to Cyprus, where he was appointed by Barnabas and Paul the Apostle as the first bishop of Kition (present-day Larnaca). He is said to have lived there for another thirty years, serving as bishop, and upon his death, he was buried there for the second and final time.

To further establish the apostolic nature of Lazarus's appointment, tradition holds that the bishop's omophorion (a liturgical vestment) was personally presented to Lazarus by the Virgin Mary, who had woven it herself. Such apostolic connections were crucial to the claims of autocephaly (self-governance) made by the bishops of Kition, who were initially subject to the Patriarch of Jerusalem. The Church of Kition was ultimately declared self-governing in 431 AD at the Third Ecumenical Council.

A notable tradition states that Lazarus never smiled during the thirty years following his resurrection, burdened by the sight of unredeemed souls he had encountered during his four-day stay in the realm of the dead. The only recorded exception occurred when, upon seeing someone stealing a pot, he reportedly smiled and remarked, "The clay steals the clay."

In 890, a tomb was discovered in Larnaca bearing the inscription "Lazarus the friend of Christ." Emperor Leo VI of Byzantium ordered Lazarus's remains to be transferred to Constantinople in 898. This transfer was eulogized by Arethas, bishop of Caesarea, and is commemorated by the Eastern Orthodox Church annually on October 17. In recompense to Larnaca, Emperor Leo had the magnificent Church of St. Lazarus, which still stands today, erected over Lazarus's tomb. The marble sarcophagus believed to be his can be seen inside the church, located under the Holy of Holies.

In the 16th century, a Russian monk from the Monastery of Pskov visited Lazarus's tomb in Larnaca and took a small piece of the relics with him. This relic likely led to the construction of the St. Lazarus chapel at the Pskov Monastery (Spaso-Eleazar Monastery, Pskov), where it is preserved to this day. In November 1972, during renovation works in the Church of St. Lazarus at Larnaca, human remains in a marble sarcophagus were discovered under the altar and were identified as part of the saint's relics. In June 2012, the Church of Cyprus presented a portion of these holy relics to a delegation of the Russian Orthodox Church, led by Patriarch Kirill of Moscow and All Russia, during a four-day visit to Cyprus. The relics were transported to Moscow and entrusted to Archbishop Arseniy of Istra, who placed them at the Zachatievsky monastery for veneration.

3.2. Bishop of Marseille (Provence)

In the West, an alternative medieval tradition, primarily centered in Provence, holds that Lazarus, Mary, and Martha were set adrift at sea by Jews hostile to Christianity. Their vessel, without sails, oars, or a helm, miraculously landed in Provence at a place now called the Saintes-Maries. According to this tradition, the family then separated to preach in different parts of southeastern Gaul. Lazarus is said to have traveled to Marseille, where he converted many people to Christianity and became the city's first Bishop of Marseille. During the persecution under Domitian, he was imprisoned and beheaded in a cave beneath the prison of Saint-Lazare. His body was later translated to Autun, where he is reportedly buried in the Autun Cathedral, which is dedicated to Lazarus as Saint Lazare. However, the inhabitants of Marseille maintain their claim to possess his head, which they continue to venerate.

Pilgrims also visit another purported tomb of Lazarus at the Vézelay Abbey in Burgundy. Additionally, the Abbey of the Trinity at Vendôme was said to house a tear shed by Jesus at the tomb of Lazarus.

The Golden Legend, a collection of hagiographies compiled in the 13th century, records the Provençal tradition. It also presents an imagined opulent lifestyle for Lazarus and his sisters, identifying Lazarus's sister Mary with Mary Magdalene. It states: "Mary Magdalene had her surname of Magdalo, a castle, and was born of right noble lineage and parents, which were descended of the lineage of kings. And her father was named Cyrus, and her mother Eucharis. She with her brother Lazarus, and her sister Martha, possessed the castle of Magdalo, which is two miles from Nazareth, and Bethany, the castle which is nigh to Jerusalem, and also a great part of Jerusalem, which, all these things they departed among them. In such wise that Mary had the castle Magdalo, whereof she had her name Magdalene. And Lazarus had the part of the city of Jerusalem, and Martha had to her part Bethany. And when Mary gave herself to all delights of the body, and Lazarus entended all to knighthood, Martha, which was wise, governed nobly her brother's part and also her sister's, and also her own, and administered to knights, and her servants, and to poor men, such necessities as they needed. Nevertheless, after the ascension of our Lord, they sold all these things."

The 15th-century poet Georges Chastellain also drew upon the tradition of the unsmiling Lazarus in his work Le pas de la mort: "He whom God raised, doing him such grace, the thief, Mary's brother, thereafter had naught but misery and painful thoughts, fearing what he should have to pass."

4. Theological Interpretation and Critical Perspectives

The raising of Lazarus by Jesus is a richly interpreted event within Christian theology and has also been the subject of extensive historical and critical analysis by scholars.

4.1. Theological Significance

The miracle of the raising of Lazarus is considered the climax of John's "signs", a series of miracles that demonstrate Jesus's divine nature and power. This event is depicted as directly explaining the large crowds who sought Jesus on Palm Sunday and is presented as the immediate catalyst for the decision by Caiaphas and the Sanhedrin to plan Jesus's death. Theologians Moloney and Harrington describe the raising of Lazarus as a "pivotal miracle," initiating the chain of events that would lead to the Crucifixion of Jesus. They view it as a "resurrection that will lead to death," as Lazarus's raising ultimately leads to the death of Jesus, the Son of God, in Jerusalem, thereby revealing the Glory of God.

The Catechism of the Catholic Church clarifies that Jesus's miracle returned Lazarus to ordinary earthly life, similar to the son of the widow of Nain and Jairus's daughter. Like these others, Lazarus would eventually die again. This contrasts sharply with Christ's own Resurrection, which is fundamentally different as Jesus passed from the state of death to a new life beyond time and space in his risen body. The Russian Orthodox Church's Catechism of St. Philaret also affirms Jesus's raising of Lazarus from the dead on the fourth day. The Southern Baptist Convention's 2014 resolution "On the Sufficiency of Scripture Regarding the Afterlife" notes Lazarus's raising among the Bible's "explicit accounts of persons raised from the dead," but emphasizes that "in God's perfect revelatory wisdom, He has not given us any report of their individual experience in the afterlife."

John Calvin remarked that in raising Lazarus, Christ not only provided "a remarkable proof of his Divine power" but also presented "a lively image of our future resurrection." French Protestant minister Jakob Abbadie suggested that Jesus intentionally delayed his return to Bethany for "four days, that it might not be said, he [Lazarus] was not really dead." In 2008, Pope Benedict XVI stated that the Gospel story of Lazarus's raising "shows Christ's absolute power over life and death and reveals His nature as true man and and true God," adding that "Jesus' lordship over death does not prevent him from showing sincere compassion over the pain of this separation."

Regarding the detail of Lazarus being bound by grave-cloths, Matthew Poole and others interpreted Lazarus's ability to move despite being wrapped "hand and foot" as a second miracle. However, Charles Ellicott disputed this, arguing that Lazarus's movement would not have been restricted by his burial garments, suggesting they may have been bound around the limbs separately or were a general linen sheet allowing motion.

Justus Knecht explained that the purpose of this miracle, performed close to the time of Jesus's Passion and Death, was "in order that the faith of His disciples, and more especially of His apostles, might be strengthened, and 'that they might believe' and not doubt when they saw their Lord and Master in the hour of His abasement; and most of all to enable them to hope, when they saw His Body laid in the sepulchre, that He who had raised up Lazarus would Himself rise again."

In his Meditations, Roger Baxter reflected on the sisters' message, "His sisters therefore sent to Him saying, Lord, behold he whom Thou lovest is sick," noting that "they do not prescribe to Him what they wish Him to do; to a loving friend it is sufficient to intimate our necessities. Such ought to be the nature of our prayers, particularly in regard to health and other temporal blessings, for we do not know in such cases what is expedient for our salvation."

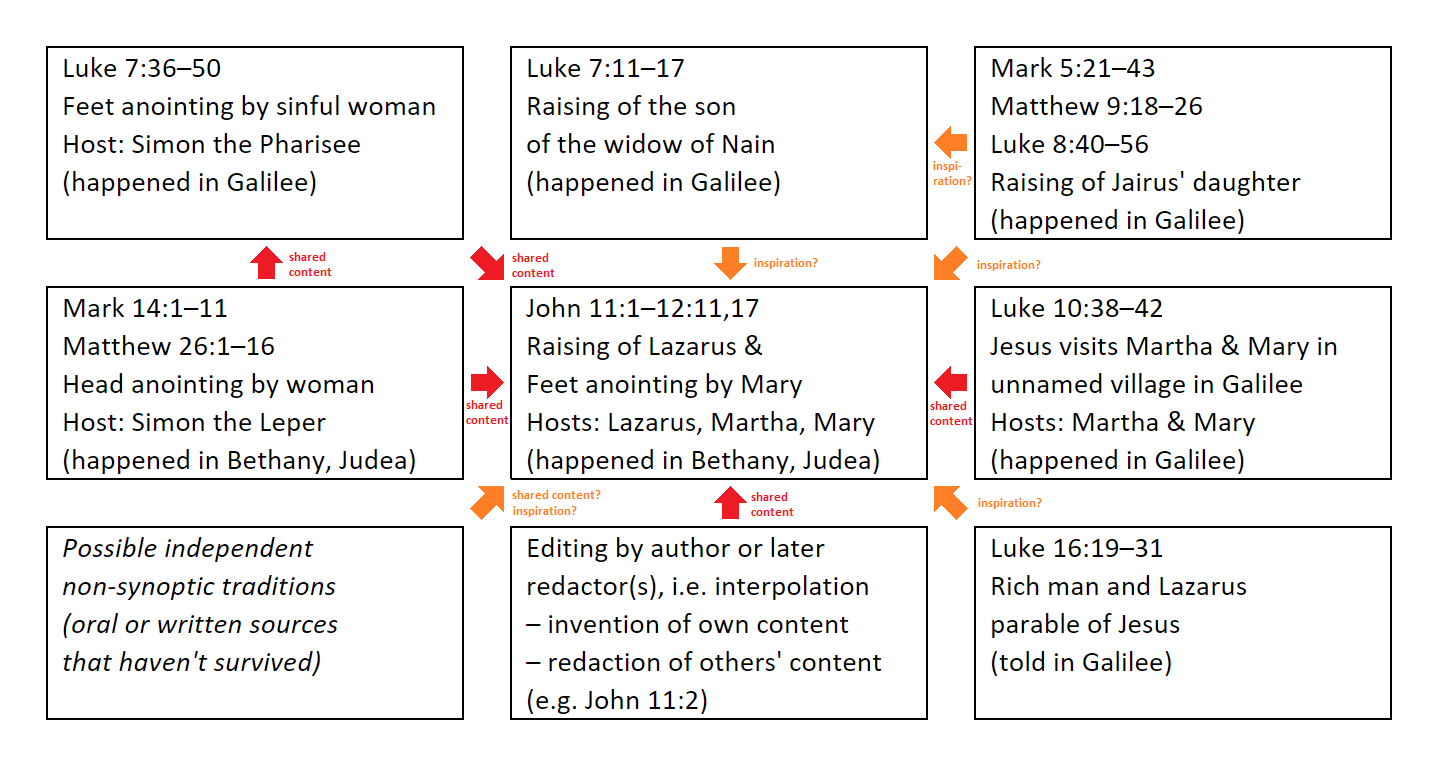

4.2. Historical and Critical Analysis

New Testament scholars often employ narrative criticism to understand the composition of John's account of the raising of Lazarus and the subsequent feet-anointing of Jesus by Mary of Bethany (John 11:1-12:11,17). They aim to explain its apparent relationships with older textual traditions found in the Synoptic Gospels (Mark, Matthew, and Luke). One prevailing theory suggests that the author of John may have synthesized elements from several, originally unrelated, stories into a single narrative. These potentially include the unnamed woman's head-anointing of Jesus in Bethany (Mark 14, Matthew 26), the sinful woman's feet-anointing (and hair-wiping) of Jesus in Galilee (Luke 7), Jesus's visit to Martha and Mary in an unnamed Galilean village (Luke 10), Jesus's parable of the rich man and Lazarus (Luke 16), and possibly other accounts of Jesus's miraculous raising of the dead, such as the raising of Jairus' daughter and the raising of the son of the widow of Nain.

Conversely, some elements from these earlier traditions appear to have been removed or altered in John's account. For example, Simon the Leper or Simon the Pharisee was replaced by Lazarus as the host of the feast honoring Jesus. Additionally, Bethany in Judea was chosen as the setting in John, whereas most corresponding elements in the Synoptics are set in Galilee. Scholars particularly scrutinize John 11 (and verse 11:1), which some believe represents an attempt by the author or a later redactor to emphasize a connection between these stories that was not present in the older canonical gospels. They note that the anointing itself is not narrated until John 12:3, and that neither Mary, Martha, their village, nor any anointing is mentioned earlier in John's Gospel, suggesting the author assumed readers already possessed knowledge of these characters and events, and aimed to link them before providing further details. Esler and Piper (2006) proposed that John 11:2 indicates the author deliberately blended traditions in an "audacious attempt (...) to rework the collective memory of the Christ-movement," not striving for historical accuracy but constructing Lazarus, Mary, and Martha as a prototypical Christian family for theological purposes. However, Zangenberg (2023) expresses doubt about John 11's dependence on the synoptic stories, citing insufficient evidence and arguing that John demonstrates accurate knowledge of Jewish burial customs of the time, supported by archaeological and ancient Jewish texts.

Earlier critical commentators also weighed in on the narrative's historicity. The deist Lysander Spooner wrote in 1836 that the omission of the raising of Lazarus from the Synoptic Gospels (Matthew, Mark, and Luke) was unusual, given its potential as a powerful demonstration of Jesus's miraculous abilities. Spooner suggested this omission indicated that the author of the Gospel of John "was actually dishonest, or that he took up, believed and recorded a flying story, which an occurrence of some kind had given rise to, but which was without any foundation in truth." In 1892, the agnostic speaker Robert G. Ingersoll found the narrative historically implausible. He argued that if Lazarus had indeed died, potentially experienced an afterlife, and then been resurrected, his experiences would have been more compelling than anything else in the New Testament, drawing widespread attention throughout his life and likely making him less fearful of his second death than others who had not shared his experience.

An Exegesis in the Interpreter's Bible (1953) compared the raising of Lazarus to other resurrections in the Bible, commenting that "The difference between revival immediately after death, and resurrection after four days, is so great as to raise doubts about the historicity of this story, especially in view of the unimaginable details in vs. 44. Yet there are features in this story which have the marks of verisimilitude." Other scholars propose that the events leading to Jesus's death in the Synoptic Gospels were based on an earlier account written before the Gospel of Mark, in which many characters remained anonymous to protect them from persecution while they were still alive. In contrast, John's account, written much later, could name the anonymous characters and include the raising of Lazarus because all individuals involved had already died and were no longer subject to persecution.

5. Liturgical Commemorations

Lazarus is honored as a saint in various Christian churches that observe the commemoration of saints, though the specific dates of his feast day vary according to local traditions. In Christian funerals, the prayer often expresses the hope that the deceased will be raised by the Lord, just as Lazarus was.

5.1. Eastern Orthodoxy

The Eastern Orthodox Church and Byzantine Catholic Church commemorate Lazarus on Lazarus Saturday, which is the day immediately preceding Palm Sunday. This is a moveable feast day, meaning its date changes each year relative to Easter. Lazarus Saturday, together with Palm Sunday, occupies a unique position in the church year, serving as a period of profound joy and triumph nestled between the penitential season of Great Lent and the solemn mourning of Holy Week.

Throughout the week preceding Lazarus Saturday, the hymns found in the Lenten Triodion meticulously recount the progression of Lazarus's illness, his subsequent death, and Christ's journey from beyond the Jordan River to Bethany. The scripture readings and hymns specifically designated for Lazarus Saturday concentrate on the resurrection of Lazarus as a powerful foreshadowing of the Resurrection of Christ itself, and as a concrete promise of the General Resurrection of all believers. The Gospel narrative of Lazarus's raising is interpreted in the liturgical hymns as illustrating the two natures of Christ: His humanity is revealed when He asks, "Where have ye laid him?", while His divinity is manifested in His authoritative command, "Lazarus, come forth!" from the dead. Many of the resurrectional hymns typically chanted during the normal Sunday service, which are notably omitted on Palm Sunday, are instead sung on Lazarus Saturday. During the Divine Liturgy on this day, the Baptismal Hymn, "As many as have been baptized into Christ have put on Christ," is sung in place of the Trisagion. Although the forty days of Great Lent officially conclude on the day before Lazarus Saturday, the day itself is still observed as a fast; however, the strictness of the fast is somewhat mitigated. In Russia, it is a traditional practice to eat caviar on Lazarus Saturday.

Lazarus is also commemorated on the fixed feast day of March 17 on the liturgical calendar of the Eastern Orthodox Church. Additionally, the translation of his relics from Cyprus to Constantinople in 898 AD is observed on October 17. The Prologue from Ohrid notes that Lazarus's principal feasts are on March 17 and Lazarus Saturday during Great Lent. It further states that the translation occurred when Emperor Leo VI the Wise built the Church of St. Lazarus in Constantinople and translated Lazarus's relics there in 890. When Lazarus's grave in Kition on Cyprus was unearthed almost a thousand years later, a marble tablet inscribed "Lazarus of the Four Days, the friend of Christ" was found.

5.2. Roman Catholicism and Other Western Churches

In the General Roman Calendar, Lazarus is celebrated, along with his sisters Mary and Martha, on a memorial on July 29. Prior to this, earlier editions of the Roman Martyrology listed him among the saints commemorated on December 17.

In Cuba, the celebration of San Lázaro on December 17 is a significant annual festival. The date is observed with a major pilgrimage to a chapel that houses an image of Saint Lazarus, considered one of Cuba's most sacred icons, located in the village of El Rincon, just outside Havana.

Lazarus is also commemorated in the calendars of some Anglican provinces. The Church of England remembers Lazarus (together with Martha and Mary) under the title "Mary, Martha, and Lazarus, Companions of Our Lord," on July 29, observing it as a Lesser Festival. This commemoration includes proper lectionary readings and a collect. Similarly, the Lutheran Church commemorates Lazarus in its Calendar of Saints on July 29, alongside Mary and Martha.

6. Distinction from Lazarus the Beggar

The name "Lazarus" appears in two distinct narratives in the New Testament, leading to occasional conflation between the two figures. The first is Lazarus of Bethany, who was miraculously resurrected by Jesus in the Gospel of John. The second is the beggar Lazarus, who appears in Jesus's parable of the rich man and Lazarus (also known as "Dives and Lazarus" or "The Rich Man and the Beggar Lazarus") in Luke 16:19-31. This parable describes the relationship between an unnamed wealthy man and a poor beggar named Lazarus, both in life and in death. In the parable, after dying, the rich man is tormented in Hell and calls to Abraham in Heaven, requesting that Lazarus be sent from Abraham's side to warn the rich man's living family against sharing his fate. Abraham responds by saying, "If they do not listen to Moses and the Prophets, they will not be convinced even if someone rises from the dead."

Historically, within Christianity, the begging Lazarus of the parable (whose feast day is traditionally June 21) and Lazarus of Bethany have sometimes been conflated. This conflation is evident in iconography, where both figures are occasionally depicted with sores and crutches. Examples of this can be found in Romanesque carvings on portals in Burgundy and Provence. For instance, at the west portal of the Church of St. Trophime at Arles, the beggar Lazarus is notably enthroned as Saint Lazarus. Similar artistic representations appear at the church in Avallon, the central portal at Vézelay, and on the portals of the Autun Cathedral.

6.1. Order of Saint Lazarus

The Order of Saint Lazarus of Jerusalem is a chivalric order that traces its origins to a leper hospital. This hospital was founded in the 12th century by Knights Hospitaller within the Crusader-era Latin Kingdom of Jerusalem. Those suffering from leprosy traditionally regarded the beggar Lazarus, as depicted in Luke 16:19-31, as their patron saint, and consequently, their hospices were often dedicated in his honor.

7. In Other Religious Traditions

Beyond Christianity, Lazarus is recognized or interpreted within other religious traditions, reflecting diverse cultural and spiritual encounters with his story.

7.1. Islam

Lazarus, known as Al-ʿĀzir (العازرAl-ʿĀzirArabic), also appears in medieval Islamic tradition, where he is honored as a pious companion of Jesus (Isa). Although the Quran does not specifically mention a figure named Lazarus, it attributes to Jesus the miracle of raising people from the dead, as stated in QS. Al-Imran [3]]:49. Islamic lore frequently elaborated upon these miraculous narratives attributed to Jesus, though Lazarus is mentioned only occasionally. For example, Al-Ṭabarī, in his Taʾrīkh, refers to these miracles in general terms. However, Al-Thaʿlabī recounted a narrative closely mirroring the Gospel of John's account: "Lazarus [Al-ʿĀzir] died, his sister sent to inform Jesus, Jesus came three (in the Gospel, four) days after his death, went with his sister to the tomb in the rock and caused Lazarus to arise; children were born to him." Similarly, in the works of Ibn al-Athīr, the resurrected man is referred to as "ʿĀzir", which is another Arabic rendering of "Lazarus".

7.2. Santería

Through syncretism, Lazarus (more precisely, a conflation of both biblical figures named Lazarus) has become a prominent figure in Santería as the Yoruba deity Babalú-Ayé. This assimilation is rooted in shared iconography and attributes: like the beggar Lazarus of the Christian Gospel of Luke, Babalú-Ayé is often depicted as an individual covered with sores, licked by dogs, who was subsequently healed by divine intervention.

Silver charms, often referred to as the crutch of St. Lazarus, or standard Roman Catholic-style medals depicting St. Lazarus, are worn as talismans by adherents to invoke the aid of this syncretized deity. This practice is particularly common in cases of medical suffering, notably among people with HIV/AIDS. In Santería, the date associated with Saint Lazarus is December 17, aligning with the traditional Catholic feast day for the beggar Lazarus, despite the Santería iconography being more closely tied to the begging saint whose original feast day is June 21.

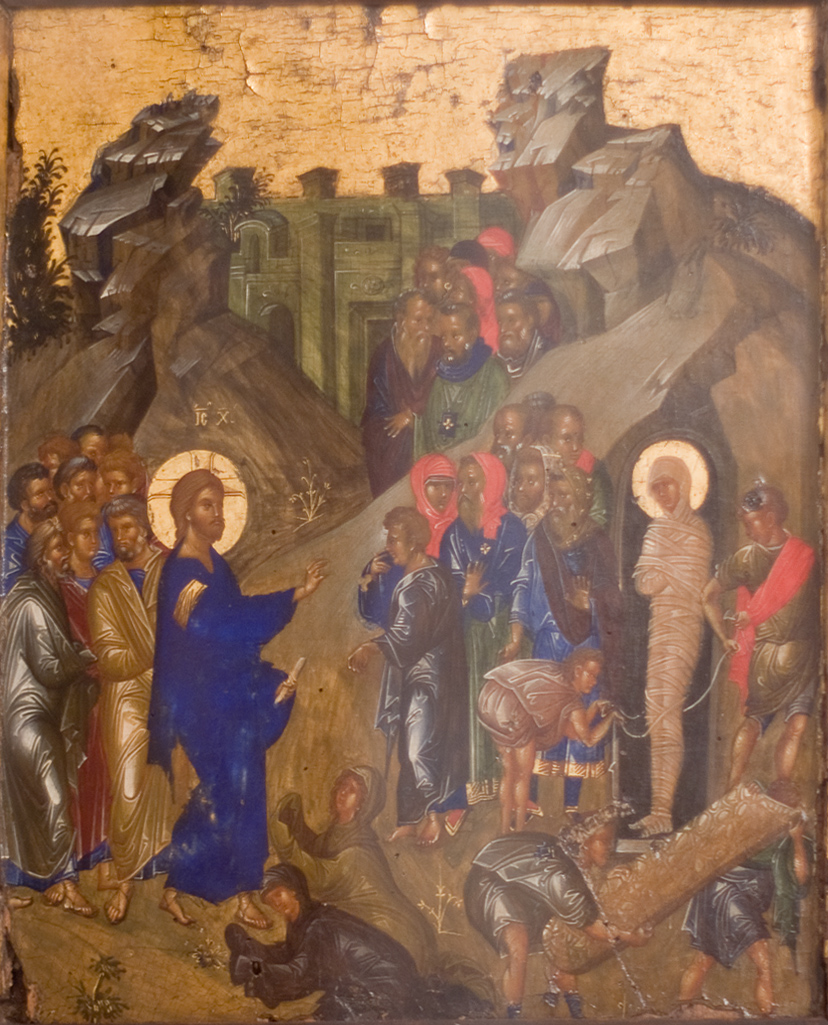

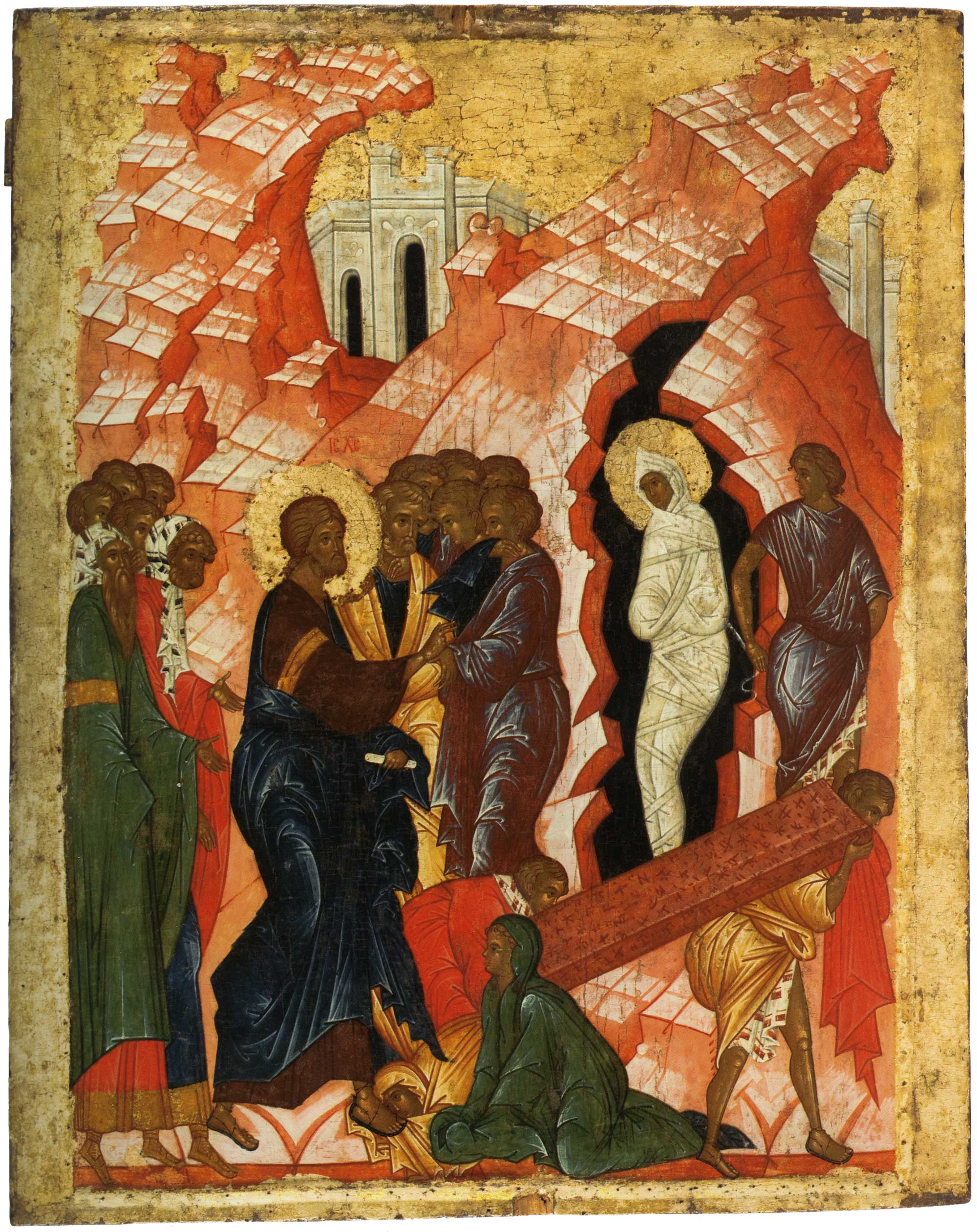

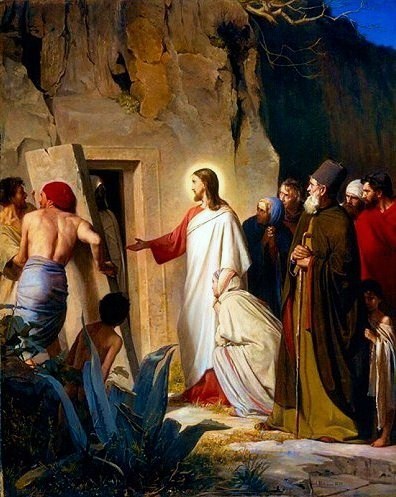

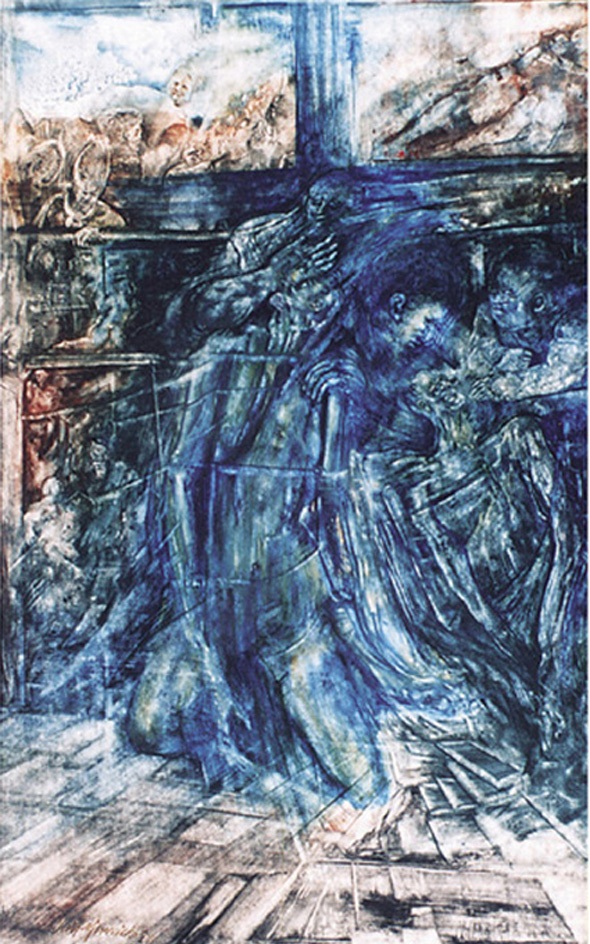

8. Depictions in Art

The raising of Lazarus is a widely popular subject in religious art, inspiring numerous works across different periods and styles. Notable paintings include those by Michelangelo Merisi da Caravaggio (circa 1609) and Sebastiano del Piombo (1516). Other prominent artists who depicted Lazarus include Rembrandt, Van Gogh, Ivor Williams, and Walter Sickert, whose work Lazarus Breaking His Fast is well-known.

The Raising of Lazarus is also one of the most frequently depicted artistic themes found in the Catacombs of Rome, with examples dating back to the 2nd century.

Medieval and Renaissance depictions often captured the dramatic miracle.

Later artists continued to explore the narrative with various styles.

Artists from the Dutch Golden Age to modern times reinterpreted the scene.

Other notable works from various periods include:

9. In Popular Culture

Both the figure of Lazarus of Bethany and the beggar Lazarus from the parable of "Lazarus and Dives" are well-known in Western culture from their respective biblical tales, and as such, have appeared numerous times in music, literature, and various other forms of art and popular media. The majority of these references, however, are to Lazarus of Bethany.

9.1. Literature

Lazarus has been a recurring motif in literature, often symbolizing themes of resurrection, renewed life, and trauma. In the 1851 novel Moby-Dick by Herman Melville, the narrator Ishmael, after writing his will and testament for the fourth time, remarks that "all the days I should now live would be as good as the days that Lazarus lived after his resurrection; a supplementary clean gain of so many months or weeks as the case might be." In Fyodor Dostoevsky's 1866 novel Crime and Punishment, the protagonist Raskolnikov specifically asks his lover Sonia to read him the section of the Gospel concerning Lazarus's resurrection, marking a pivotal moment in his journey towards confession and redemption.

In two short stories written by Mark Twain and posthumously published in 1972, a lawyer humorously argues that Lazarus's heirs would have an indisputable claim to any property Lazarus had owned before his death, as he would have found himself penniless upon his resurrection. Playwright Eugene O'Neill explored Lazarus's life after his resurrection in his 1925 play Lazarus Laughed, which features a large cast and has been produced in various forms.

Numerous 20th-century literary works allude to Lazarus. These include Truman Capote's short story "A Tree of Night" from his 1945 collection A Tree of Night and Other Stories and John Knowles's 1959 novel A Separate Peace. In poetry, allusions appear in works such as Leonid Andreyev's book-length poem Lazarus (1906), T.S. Eliot's iconic poem "The Love Song of J. Alfred Prufrock" (1915), Edwin Arlington Robinson's poem "Lazarus" (1920), and Sylvia Plath's famous poem "Lady Lazarus", published in her posthumous 1965 anthology Ariel. The memoir Witness (1952) by Whittaker Chambers, who was influenced by Dostoevsky, opens its first chapter with a direct allusion: "In 1937, I began, like Lazarus, the impossible return."

Science fiction has also drawn on the Lazarus theme. Examples include Robert A. Heinlein's Lazarus Long novels (1941-1987), Walter M. Miller Jr.'s A Canticle for Leibowitz (1960), and Frank Herbert's The Lazarus Effect (1983). In the 2010 philosophy textbook The Big Questions: A Short Introduction to Philosophy by American professors Kathleen Higgins and Robert C. Solomon, readers are posed with the question: "Could a scientist give an adequate account of the biblical story of the raising of Lazarus?"

More recent novels include Lazarus Is Dead (2011) by Richard Beard, an innovative work that expands on the Gospel detail of Jesus and Lazarus's friendship, tracing their story from childhood in Nazareth and exploring their divergent paths. It was described as a "brilliant, genre-bending retelling and subversion of one of the oldest, most sensational stories in the western canon." John Derhak's The Bones of Lazarus (2012) is a supernatural thriller that posits Lazarus of Bethany, upon his resurrection, became an immortal creature of Judgment, seeking the wicked throughout time. Larry: A Novel of Church Recovery (2019) by Brian L. Boley features a character named "Larry" who provides advice to pastors on church growth, subtly revealing himself to be the biblical Lazarus, an immortal evangelistic servant of Jesus. Richard Zimler's bestselling novel The Gospel According to Lazarus (2019) is written from Lazarus's own perspective, portraying Yeshua ben Yosef (Jesus's Hebrew name) as an early Jewish mystic and delving into the deep friendship between Lazarus and Yeshua from childhood. The novel explores themes such as coping with loss of faith, making terrible sacrifices for loved ones, the transcendent meaning of Yeshua's mission, and moving forward after profound trauma. The Observer praised it as "A very human tale of rivalry, betrayal, power-grabbing and sacrifice.... Perhaps the most remarkable aspect of this brave and engaging novel...is that Zimler manages to make the best-known narrative in western culture a page-turner."

9.2. Music

Lazarus's story has also inspired numerous musical works. A notable retelling from Lazarus's perspective in heaven is the 1984 gospel story-song "Lazarus Come Forth" by Contemporary Christian Music artist Carman. A modern reinterpretation of the narrative is the title track to the album Dig, Lazarus, Dig!!! by the Australian alternative band Nick Cave and the Bad Seeds. Additionally, several other bands have composed songs titled "Lazarus" in direct allusion to the resurrection story, including Porcupine Tree, Conor Oberst, Circa Survive, Chimaira, moe., Wes King, Placebo, and David Bowie. Bowie's song, written while he was terminally ill, held particular poignancy for fans after his death.

9.3. Other Media and Allusions

Lazarus is sometimes referenced in political discourse to describe figures who return to power or prominence under highly improbable circumstances. For example, when John Howard lost the leadership of the Liberal Party of Australia, he famously rated his chances of regaining it as "Lazarus with a triple bypass." Howard subsequently did regain the leadership and went on to become Prime Minister of Australia. Similarly, former President of Haiti, Jean Bertrand Aristide, was termed the "Haitian Lazarus" by journalist Amy Wilentz in her account of his unexpected return to Haiti from exile and its political significance.

In the Batman comic book series, Ra's al Ghul is frequently restored to life by a mystical pool known as the Lazarus Pit, drawing a clear parallel to the biblical narrative. The 24th-century futuristic, dystopian, four-part television series Cold Lazarus was written by Dennis Potter while he was terminally ill. Its plot centers on attempts to resurrect the thoughts of a cryogenically frozen 20th-century writer, Danial Feeld. The Doctor Who episode "The Lazarus Experiment" features Professor Richard Lazarus, who demonstrates an experiment meant to rejuvenate him but instead transforms him into a life-force-sucking monster. In the indie roguelike video game, The Binding of Isaac, one of the playable characters is named Lazarus, who is resurrected once per floor after death. A notable real-world allusion is to a GPS satellite that was nicknamed "Lazarus" after it mysteriously revived from a malfunction, resuming its operations.