1. Early Life and Background

Khalid ibn al-Walid was born in around 585 or around 592 in Mecca, located in the Hejaz region of western Arabia. He belonged to the Banu Makhzum clan of the Quraysh tribe, which was a prominent and aristocratic lineage in pre-Islamic Mecca. His father was al-Walid ibn al-Mughira, who was known as "the derider" of the Islamic prophet Muhammad, as mentioned in the Meccan surahs of the Qur'an. Al-Walid ibn al-Mughira was also an important arbitrator of local disputes in Mecca. The Banu Makhzum were known for their intellect, nobility, and wealth, having introduced Meccan commerce to foreign markets, particularly in Yemen and Abyssinia (Ethiopia). Their influence was largely due to the leadership of Khalid's paternal grandfather, al-Mughira ibn Abd Allah. Khalid's paternal uncle, Hisham ibn al-Mughira, was referred to as the 'lord of Mecca,' and the date of his death was used by the Quraysh as the beginning of their calendar. Historian Muhammad Abdulhayy Shaban described Khalid as "a man of considerable standing" within his clan and Mecca.

Khalid's mother was al-Asma bint al-Harith ibn Hazn, commonly known as Lubaba al-Sughra, from the nomadic Banu Hilal tribe. This distinguished her from her elder half-sister, Lubaba bint al-Harith (Lubaba al-Kubra). Lubaba al-Sughra converted to Islam around 622, and her paternal half-sister, Maymuna bint al-Harith, became a wife of Muhammad. Through his maternal relatives, Khalid gained a deep understanding of the nomadic Arab way of life.

1.1. Childhood and Education

Following the custom of the Quraysh tribe, Khalid was sent to live with a Bedouin tribe in the desert immediately after his birth. There, he was nursed and raised by a foster mother in the dry, clean air of the desert environment, which was believed to promote good health and strong character. He returned to his parents in Mecca when he was about five or six years old. During his childhood, Khalid contracted smallpox, and although he recovered, the disease left scars on his left cheek.

Khalid was known for his physical prowess from a young age. He was tall, well-built, and broad-shouldered, with a thick beard. He excelled as a champion wrestler among the Quraysh. As a member of the Banu Makhzum, a clan renowned for its military expertise and horsemanship, Khalid learned to ride horses and master various weapons, including the spear, lance, bow, and sword. The spear was reportedly his favorite weapon. In his youth, he was already celebrated as a warrior and wrestler among the Quraysh.

1.2. Ancestry and Tribal Affiliation

The Banu Makhzum, a leading clan of the Quraysh tribe, were a core component of Mecca's pre-Islamic aristocracy. They were strongly opposed to Muhammad's early teachings. Khalid's first cousin, Amr ibn Hisham (also known as Abu Jahl), was a prominent leader of the Makhzum and organized a boycott against Muhammad's clan, the Banu Hashim, around 616-618. This strong opposition defined the early relationship between Khalid's clan and the nascent Muslim community.

2. Pre-Islamic Life and Opposition to Muhammad

Before his conversion to Islam, Khalid ibn al-Walid was a formidable military leader for the Quraysh tribe in Mecca, actively opposing Muhammad. The Makhzum clan, led by Abu Jahl, commanded the war against Muhammad after his emigration from Mecca to Medina in 622. However, they suffered a significant defeat at the Battle of Badr in 624, an engagement in which Khalid did not participate. Approximately twenty-five of Khalid's paternal cousins, including Abu Jahl, and numerous other kinsmen were killed in this battle. Khalid's brother, al-Walid ibn al-Walid, was captured during the battle but later escaped and converted to Islam in Medina.

In 625, Khalid played a critical role in the Battle of Uhud, fought north of Medina. Commanding the right flank of the Meccan cavalry, Khalid employed a strategic maneuver by circling Mount Uhud to bypass the Muslim flank, rather than launching a frontal assault. He advanced through the Wadi Qanat valley, west of Uhud, until he was checked by Muslim archers positioned at Mount Ruma. Although the Muslims initially gained the upper hand, Khalid seized the opportunity when most of the Muslim archers abandoned their positions to loot the Meccan camp. He charged into the resulting gap in the Muslim rear defensive lines, causing a rout in which several dozen Muslims were killed. Narratives of the battle depict Khalid riding through the field, slaying Muslims with his lance. Historian Muhammad Abdulhayy Shaban credits Khalid's "military genius" for securing the Quraysh's victory at Uhud, which was their only successful engagement against Muhammad.

In 628, when Muhammad and his followers intended to perform the lesser pilgrimage (ʿumrahumrahArabic) to Mecca, the Quraysh dispatched 200 cavalry to intercept them. Khalid led this cavalry force. Muhammad, aware of Khalid's presence, avoided a direct confrontation by taking an unconventional and difficult alternate route, eventually reaching Hudaybiyya at the edge of Mecca. Upon realizing Muhammad's change of course, Khalid withdrew to Mecca. A truce between the Muslims and the Quraysh, known as the Treaty of Hudaybiyya, was subsequently signed in March of that year.

3. Conversion to Islam and Service under Muhammad

Khalid's conversion to Islam marked a significant turning point in his life and for the nascent Muslim state, as he dedicated his formidable military talents to its cause.

3.1. Conversion and Title

Khalid embraced Islam in the presence of Muhammad, either in 6 AH (around 627) or 8 AH (around 629), alongside the Qurayshite Amr ibn al-As. Modern historian Michael Lecker suggests that accounts placing their conversion in 8 AH are "perhaps more trustworthy." Historian Akram Diya Umari states that Khalid and Amr relocated to Medina after the Treaty of Hudaybiyya, seemingly after the Quraysh ceased demands for the extradition of new Muslim converts to Mecca. According to Hugh N. Kennedy, following his conversion, Khalid "began to devote all his considerable military talents to the support of the new Muslim state." It is recorded that Muhammad had previously stated to Khalid's brother, Walid ibn al-Walid, "A man like Khalid, he will not be able to distance himself from Islam for long." Khalid, who was reportedly unenthused by the idols in the Kaaba, made his decision to convert after receiving a letter from his brother.

After his successful command during the Battle of Mu'tah, Muhammad bestowed upon Khalid the honorary title Sayf AllāhSayf AllahArabic ('the Sword of God'). However, the exact timing and location of this bestowal vary in Islamic sources. Some 8th and early 9th-century historians indicate the title was awarded by Caliph Abu Bakr for Khalid's successes in the Ridda Wars, while mid-to-late 9th-century reports credit Muhammad for his role at Mu'tah.

3.2. Military Campaigns under Muhammad

In September 629, Khalid participated in the Battle of Mu'tah expedition in modern-day Jordan, ordered by Muhammad. The raid's purpose might have been to acquire spoils following the Sasanian Persian army's retreat from Syria after its defeat by the Byzantine Empire. The Muslim detachment was routed by a Byzantine force, largely composed of Arab tribesmen led by the Byzantine commander Theodore, resulting in the deaths of several high-ranking Muslim commanders. Khalid assumed command after their deaths and, with great difficulty, orchestrated a safe withdrawal of the Muslim forces. During the intense fighting, it is reported that Khalid broke nine swords. For his valiant efforts in saving the Muslim army from total annihilation and leading their strategic retreat, he earned the epithet "Sword of God."

In December 629 or January 630, Khalid was part of Muhammad's Conquest of Mecca. He led a nomadic contingent called muhajirat al-arabmuhajirat al-arabArabic ('the Bedouin emigrants') and spearheaded one of the two main thrusts into the city. In the ensuing skirmishes with the Quraysh, three of Khalid's men were killed, while twelve Qurayshites were slain. Later that year, Khalid commanded the Bedouin Banu Sulaym in the Muslim vanguard at the Battle of Hunayn. Here, the Muslims, bolstered by new Qurayshite converts, defeated the Thaqif tribe from Ta'if and their nomadic Hawazin allies. Following this, Khalid was appointed to destroy the idol of al-Uzza, a prominent goddess in pre-Islamic Arabian religion, located in the Nakhla area between Mecca and Ta'if. He also killed an Abyssinian woman associated with the idol.

Khalid was subsequently dispatched to invite the Banu Jadhima tribe in Yalamlam, about 50 mile (80 km) south of Mecca, to embrace Islam. However, traditional Islamic sources indicate that he attacked the tribe illicitly. In Ibn Ishaq's version, Khalid persuaded the Jadhima tribesmen to disarm and declare their embrace of Islam, but then proceeded to execute several of them. This action was reportedly in revenge for the Jadhima's killing of his uncle, Fakih ibn al-Mughira, before Khalid's conversion. Another narrative by Ibn Hajar al-Asqalani suggests Khalid misunderstood the tribesmen's acceptance of faith as a rejection or denigration of Islam, due to his unfamiliarity with their accent, and consequently attacked them. In both versions, Muhammad publicly disavowed Khalid's actions, declaring himself innocent of them, but did not discharge or punish him. Modern scholars like W. Montgomery Watt view these traditional accounts as potentially exaggerated or "circumstantial denigration of Khālid."

Later in 630, while Muhammad was at Tabuk, he sent Khalid to capture the oasis market town of Dumat al-Jandal. Khalid secured its surrender and imposed a heavy penalty on its inhabitants. One of the chiefs, Ukaydir ibn Abd al-Malik al-Sakuni of the Kindite tribe, was ordered by Khalid to sign the capitulation treaty with Muhammad in Medina. In March 631, Khalid was again sent to Dumat al-Jandal to destroy the idol Wadd and killed those who resisted. In June 631, Muhammad dispatched Khalid at the head of 480 men to invite the mixed Christian and polytheistic Balharith tribe of Najran to embrace Islam. The tribe converted, and Khalid instructed them in the Qur'an and Islamic laws before returning to Muhammad in Medina with a Balharith delegation.

4. Ridda Wars (Unification of Arabia)

After Muhammad's death in June 632, the nascent Muslim state faced significant challenges, as most tribes in Arabia, outside the immediate environs of Mecca, Medina, and Ta'if, either severed their allegiance or had never formally established relations with Medina. This period, known as the Ridda Wars (wars against the 'apostates'), saw Abu Bakr, who became the first caliph amidst initial discord over succession, consolidate Islamic rule across the Arabian Peninsula. Khalid ibn al-Walid was a staunch supporter of Abu Bakr's succession, reportedly opposing Ali ibn Abi Talib's candidacy and affirming Abu Bakr's clear character.

Islamic historiography characterizes these conflicts as wars against apostasy, while modern historians offer varied interpretations. Some, like W. Montgomery Watt, agree with the religious characterization, while others, such as Julius Wellhausen and C.H. Becker, argue the tribes primarily opposed tax obligations to Medina. Leone Caetani and Bernard Lewis suggest the tribes viewed their religious and fiscal duties as a personal contract with Muhammad, and their attempts to negotiate new terms after his death were rejected by Abu Bakr, leading to military campaigns.

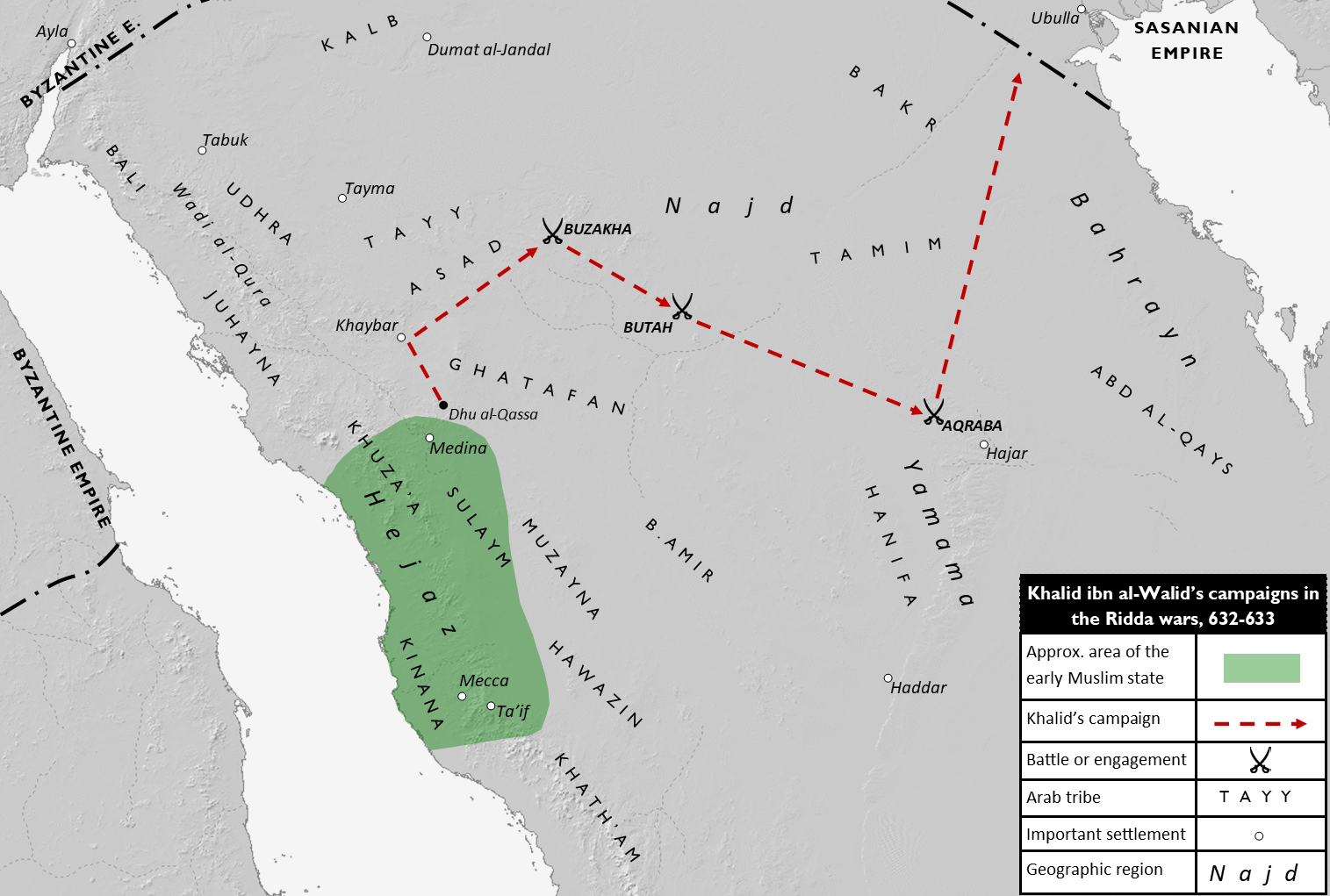

Of the six major conflict zones during the Ridda Wars, two were centered in Najd (the central Arabian plateau): the rebellion of the Asad, Tayy, and Ghatafan tribes under Tulayha, and the rebellion of the Banu Tamim tribe led by Sajah; both Tulayha and Sajah claimed to be prophets. After Abu Bakr neutralized the Ghatafan threat at the Battle of Zhu Qissa, he dispatched Khalid against the rebel tribes in Najd. Khalid was Abu Bakr's third choice for this command, after Zayd ibn al-Khattab and Abu Hudhayfa ibn Utba declined. Khalid's forces primarily consisted of the Muhajirun and the Ansar. Throughout the campaign, Khalid operated with considerable independence, often not strictly adhering to the caliph's directives, and, in the words of historian Muhammad Abdulhayy Shaban, "he simply defeated whoever was there to be defeated."

4.1. Battle of Buzakha and Suppression of Tulayha

Khalid's initial objective was to suppress Tulayha's following. In late 632, he confronted Tulayha's forces at the Battle of Buzakha, near a well in Asad territory where the rebel tribes were encamped. Before Khalid's troops arrived, the Tayy tribe defected to the Muslims due to the mediation efforts of their chief, Adi ibn Hatim, who had been appointed by Medina as its tax collector over both his tribe and their traditional rivals, the Asad.

Khalid decisively defeated the combined Asad and Ghatafan forces. As Tulayha's defeat became apparent, the Banu Fazara section of the Ghatafan, led by their chief Uyayna ibn Hisn, deserted the battlefield, forcing Tulayha to flee to Syria. Subsequently, Tulayha's tribe, the Asad, submitted to Khalid, followed by the previously neutral Banu Amir, who had awaited the outcome of the conflict before pledging allegiance. Uyayna was captured and brought to Medina. The victory at Buzakha secured Muslim control over most of Najd.

4.2. Execution of Malik ibn Nuwayra and Conquest of Yamama

After his victory at Buzakha, Khalid advanced against the rebel Tamimite chieftain Malik ibn Nuwayrah, who was headquartered in al-Butah, in the present-day Al-Qassim Region. Malik had been appointed by Muhammad as the collector of the sadaqasadaqaArabic ('alms tax') over his clan, the Yarbu of Tamim, but ceased forwarding this tax to Medina after Muhammad's death. Abu Bakr consequently ordered Khalid to execute him. This campaign caused divisions within Khalid's army, with the Ansar initially hesitant to participate, citing Abu Bakr's instructions against further campaigning without direct orders. Khalid asserted his prerogative as commander, and though he did not force the Ansar, they eventually rejoined him after internal deliberations.

According to the most common accounts in Muslim traditional sources, Khalid's army encountered Malik and eleven of his Yarbu clansmen in 632. The Yarbu did not resist and proclaimed their Muslim faith, whereupon they were escorted to Khalid's camp. Despite the objections of an Ansarite who argued for the captives' inviolability due to their declaration of faith, Khalid had them all executed. Afterward, Khalid married Malik's widow, Layla bint al-Minhal (Umm Tamim bint al-Minhal). News of Khalid's actions reached Medina, prompting Umar, then Abu Bakr's chief aide, to demand Khalid's punishment or removal from command. However, Abu Bakr pardoned him.

The 8th-century historian Sayf ibn Umar offers an alternative account, stating that Malik had been cooperating with the prophetess Sajah, a kinswoman from the Yarbu. After their defeat by rival Tamim clans, Malik abandoned Sajah's cause and retreated to al-Butah, where he was encountered by Muslim forces. Modern historian Wilferd Madelung dismisses Sayf's version, arguing that Umar and other Muslims would not have protested Khalid's actions if Malik had truly abandoned Islam. W. Montgomery Watt finds accounts of the Tamim during the Ridda period "obscure," suggesting they may have been "twisted to blacken" Khalid's reputation by his enemies. Ella Landau-Tasseron concludes that "the truth behind Malik's career and death will remain buried under a heap of conflicting traditions."

Following setbacks in her conflict with rival Tamim factions, Sajah joined forces with Musaylima, the leader of the sedentary Banu Hanifa tribe in Al-Yamama, the agricultural eastern borderlands of Najd. Musaylima had claimed prophethood even before Muhammad's emigration from Mecca, and his proposals for mutual recognition of divine revelation were rejected by Muhammad. After Muhammad's death, Musaylima gained significant support in Yamama, a region strategically valuable for its wheat fields, date palms, and its location connecting Medina to Bahrayn and Oman. Abu Bakr had already dispatched Shurahbil ibn Hasana and Khalid's cousin Ikrima ibn Abi Jahl with an army to reinforce the Muslim governor in Yamama, Musaylima's kinsman Thumama ibn Uthal. Meir Jacob Kister suggests that the threat posed by this army likely compelled Musaylima to form an alliance with Sajah. Ikrima's forces were repelled by Musaylima's army, and Abu Bakr subsequently redirected Ikrima to quell rebellions in Oman and Mahra (central southern Arabia), while Shurahbil remained in Yamama, awaiting Khalid's large army.

After his victories over the Bedouin tribes of Najd, Khalid proceeded to Yamama, having been warned of the Banu Hanifa's military prowess and instructed by Abu Bakr to deal severely with them if victorious. The 12th-century historian Ibn Hubaysh al-Asadi estimated Khalid's army at 4,500 and Musaylima's at 4,000, though Kister dismisses larger figures in early Muslim sources as exaggerations. Khalid's first three assaults against Musaylima on the plain of Aqraba were repulsed, with Muslim failures attributed to the strength of Musaylima's warriors, their superior swords, and the unreliability of the Bedouin contingents in Khalid's ranks. Khalid then heeded the advice of the Ansarite Thabit ibn Qays to exclude the Bedouins from the next engagement.

In the fourth assault against the Hanifa, the Muhajirun under Khalid and the Ansar under Thabit killed one of Musaylima's lieutenants, prompting Musaylima to flee with part of his army. The Muslims pursued the Hanifa to a large enclosed garden, which Musaylima used for a final stand. The enclosure was stormed by the Muslims, Musaylima was slain, and most of the Hanifites were either killed or wounded. The site became known as the 'garden of death' due to the high casualties suffered by both sides.

Following Musaylima's death, Khalid tasked Mujja'a ibn al-Murara, a Hanifite captured early in the campaign, with assessing the strength, morale, and intentions of the Hanifa in their Yamama fortresses. Mujja'a employed a ruse, having the tribe's women and children dress and pose as men at the fort openings to inflate their apparent numbers to Khalid. He reported to Khalid that the Hanifa still possessed numerous warriors determined to continue fighting. This assessment, combined with the exhaustion of his own troops, compelled Khalid to agree to a ceasefire with the Hanifa, despite Abu Bakr's directives to pursue retreating Hanifites and execute prisoners of war. The terms of Khalid's agreement with the Hanifa included their conversion to Islam and the surrender of their arms, armor, and stockpiles of gold and silver. Abu Bakr ratified the treaty, though he expressed reservations about Khalid's concessions, warning that the Hanifa might remain loyal to Musaylima. The treaty was further cemented by Khalid's marriage to Mujja'a's daughter. Lecker suggests that the story of Mujja'a's ruse may have been invented by Islamic tradition to justify Khalid's negotiated treaty, which resulted in significant losses for the Muslims. Khalid was granted an orchard and a field in each village covered by the treaty, while villages excluded from the agreement, such as Musaylima's hometown of al-Haddar and Mar'at, were subjected to punitive measures, with their inhabitants expelled or enslaved and the areas resettled by Tamim tribesmen.

4.3. Conclusion of the Ridda Wars

Traditional sources date the final suppression of the Arab tribes during the Ridda Wars to before March 633, though some historians, like Leone Caetani, believe campaigns might have extended into 634, particularly in Bahrayn, where resistance may have persisted until mid-634. Some early Islamic sources attribute a role to Khalid on the Bahrayn front after his victory over the Hanifa, although Elias Shoufani deems this improbable, allowing only for the possibility that Khalid sent detachments to reinforce the main Muslim commander, al-Ala al-Hadhrami.

The Muslim war efforts, in which Khalid played a vital role, successfully asserted Medina's dominance over powerful Arab tribes who sought to diminish Islamic authority in the peninsula. This restored the nascent Muslim state's prestige. According to Michael Lecker, Khalid and other Qurayshite generals "gained precious experience [during the Ridda Wars] in mobilizing large multi-tribal armies over long distances" and "benefited from the close acquaintance of the Quraysh with tribal politics throughout Arabia," crucial skills for the subsequent larger conquests.

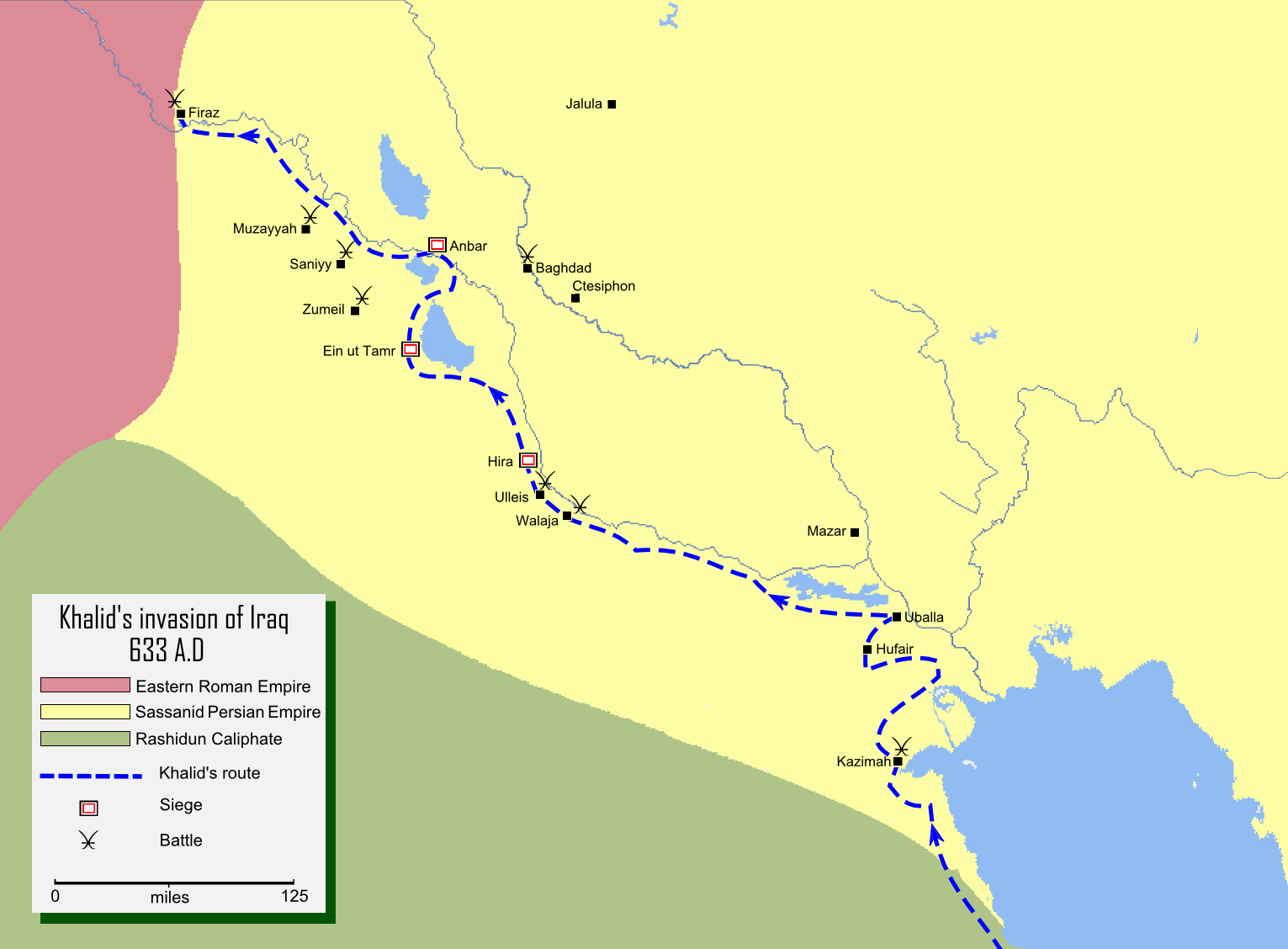

5. Campaigns in Iraq (Conquest of Persia)

With the Yamama region pacified, Khalid ibn al-Walid marched northward toward Sasanian territory in Lower Mesopotamia (modern Iraq). He reorganized his army, possibly due to the withdrawal of the main body of the Muhajirun to Medina. Historian Khalil Athamina suggests that the remaining forces were composed of nomadic Arabs from Medina's environs, whose chiefs were appointed to fill command posts left vacant by the sahabasahabaArabic ('companions' of Muhammad). However, Fred Donner maintains that the Muhajirun and the Ansar still formed the core of Khalid's army, supplemented by a large proportion of nomadic Arabs, likely from the Muzayna, Tayy, Tamim, Asad, and Ghatafan tribes. Khalid appointed Adi ibn Hatim of the Tayy and Asim ibn Amr of the Tamim as commanders of the tribal contingents. Khalid arrived at the southern Iraqi frontier with approximately 1,000 warriors in the late spring or early summer of 633.

The focus of Khalid's offensive was the western banks of the Euphrates River and the nomadic Arab tribes dwelling there. While details of the campaign's itinerary vary in early Muslim sources, Donner states that "the general course of Khalid's progress in the first part of his campaigning in Iraq can be quite clearly traced." According to 9th-century historians al-Baladhuri and Khalifa ibn Khayyat, Khalid's first major battle in Iraq was his victory over the Sasanian garrison at Ubulla (ancient Apologos, near modern Basra) and the nearby village of Khurayba. However, al-Tabari (died 923) considers this attribution to Khalid erroneous, stating Ubulla was conquered later by Utba ibn Ghazwan al-Mazini. Donner deems Utba's conquest "somewhat later than 634" more likely, while Khalid Yahya Blankinship suggests Khalid "at least may have led a raid there although [Utbah] actually reduced the area."

5.1. Initial Incursions and Battles along the Euphrates

From the vicinity of Ubulla, Khalid marched up the western bank of the Euphrates, engaging with small Sasanian garrisons guarding the Iraqi frontier from nomadic incursions. These clashes occurred at Dhat al-Salasil (Chains), Nahr al-Mar'a (a canal connecting the Euphrates with the Tigris immediately north of Ubulla), Madhar (a town several days north of Ubulla), Ullays (likely the ancient trade center of Vologesias), and Walaja. The latter two locations were near al-Hirah, a predominantly Arab market town and the Sasanian administrative center for the middle Euphrates valley.

The capture of al-Hira was the most significant gain of Khalid's campaign. After defeating the city's Persian cavalry under the commander Azadhbih in minor clashes, Khalid and part of his army entered the unwalled city. The Arab tribal nobles of al-Hira, many of whom were Nestorian Christians with ties to nomadic tribes on the city's western desert fringes, barricaded themselves in their scattered fortified palaces. Meanwhile, another part of Khalid's army harassed villages in al-Hira's orbit, many of which were captured or capitulated on tributary terms. The Arab nobility of al-Hira surrendered in an agreement with Khalid, paying an annual tribute of 60,000 or 90,000 silver dirhams in return for assurances that the city's churches and palaces would remain undisturbed. Khalid forwarded this sum to Medina, marking the first tribute the Caliphate received from Iraq.

During these engagements in and around al-Hira, Khalid received crucial assistance from al-Muthanna ibn Haritha and his Shayban tribe, who had been raiding this frontier for a considerable period before Khalid's arrival. Although it is unclear if al-Muthanna's earlier activities were linked to the nascent Muslim state, Khalid left al-Muthanna in practical control of al-Hira and its vicinity after his departure. Khalid also received similar support from the Sadus clan of the Banu Dhuhl tribe under Qutba ibn Qatada and the Banu Ijl tribe under al-Madh'ur ibn Adi during the battles at Ubulla and Walaja. However, none of these tribes, all branches of the Banu Bakr confederation, joined Khalid when he operated outside of their tribal areas.

Khalid continued northward along the Euphrates valley, attacking Anbar on the east bank, where he secured capitulation terms from its Sasanian commander. He then plundered the surrounding market villages frequented by tribesmen from the Bakr and Quda'a confederations, before moving against Ayn al-Tamr, an oasis town west of the Euphrates, about 56 mile (90 km) south of Anbar. Khalid faced stiff resistance there from the Namir tribesmen, forcing him to besiege the town's fortress. The Namir were led by Hilal ibn Aqqa, a Christian chieftain allied with the Sasanians, whom Khalid crucified after defeating him. Ayn al-Tamr capitulated, and Khalid captured the town of Sandawda to the north. By this stage, Khalid had largely subjugated the western areas of the lower Euphrates and the nomadic tribes residing there, including the Namir, Taghlib, Iyad, Taymallat, and most of the Ijl, as well as the settled Arab tribesmen. In November 633, Khalid engaged in night raids against large Persian and Christian Arab forces in the Euphrates region, including battles at Muzayyah, Saniyy, and Zumail, defeating these combined forces. The Battle of Firaz in December 633, involving mixed Persian, Byzantine, and Christian Arab troops, marked the final battle for the conquest of lower Mesopotamia. During his time in Iraq, Khalid also served as the military governor of the conquered territories.

5.2. Modern Assessments of the Iraq Campaign

The historical consensus regarding Khalid's initiative and role in the Iraq campaign is a subject of scholarly debate. Khalil Athamina questions the traditional Islamic narrative that Abu Bakr ordered Khalid to launch the campaign in Iraq. He notes Abu Bakr's apparent disinterest in Iraq, as the Muslim state's resources at the time were primarily focused on the conquest of Syria, a region where the Quraysh had pre-Islamic trading interests, unlike Iraq. Muhammad and the early Muslims had not previously prioritized Iraq for conquest. Muhammad Abdulhayy Shaban highlights the ambiguity in sources regarding whether Khalid requested or received Abu Bakr's sanction for the raids into Iraq, or if he acted against the caliph's objections. Athamina points to hints in traditional sources that Khalid initiated the campaign unilaterally, suggesting that the return of many Muhajirun in Khalid's ranks to Medina after Musaylima's defeat may have been a protest against Khalid's ambitions in Iraq. Shaban further posits that the tribesmen who remained in Khalid's army were primarily motivated by the prospect of war booty, especially amidst an economic crisis in Arabia following the Ridda campaigns.

Fred Donner suggests that Khalid's main objective in Iraq might have been the subjugation of the Arab tribes, with clashes against Persian troops being an inevitable, if incidental, consequence of these tribes' alliances with the Sasanian Empire. Hugh Kennedy views Khalid's push toward the Iraqi desert frontier as "a natural continuation of his work" in subduing the tribes of northeastern Arabia, aligning with Medina's policy to bring all nomadic Arab tribes under its authority. Wilferd Madelung argues that Abu Bakr relied on the Qurayshite aristocracy during the Ridda Wars and early Muslim conquests, speculating that the caliph dispatched Khalid to Iraq to ensure the Banu Makhzum's interests in that region.

The extent of Khalid's overall role in the conquest of Iraq remains debated by modern historians. Patricia Crone argues that it is improbable Khalid played any significant role on the Iraqi front. She cites contradictions in contemporary, non-Arabic sources, specifically the Armenian chronicle of Sebeos (around 661) and the Khuzistan Chronicle (around 680). The former records Arab armies being sent to conquer Iraq only after the Muslim conquest of Syria was already underway, rather than before, as traditional Islamic sources assert. The latter chronicle mentions Khalid solely as the conqueror of Syria. Crone interprets these discrepancies as part of a broader theme in the largely Iraq-based, Abbasid-era (post-750) sources to shift the focus of early Muslim conquests from Syria to Iraq. R. Stephen Humphreys considers Crone's assessment a "radical critique of the [traditional] sources," while Khalid Yahya Blankinship deems it "too one-sided." Blankinship notes that Khalid's prominence as a hero in Iraqi historical traditions strongly suggests his early participation in its conquest.

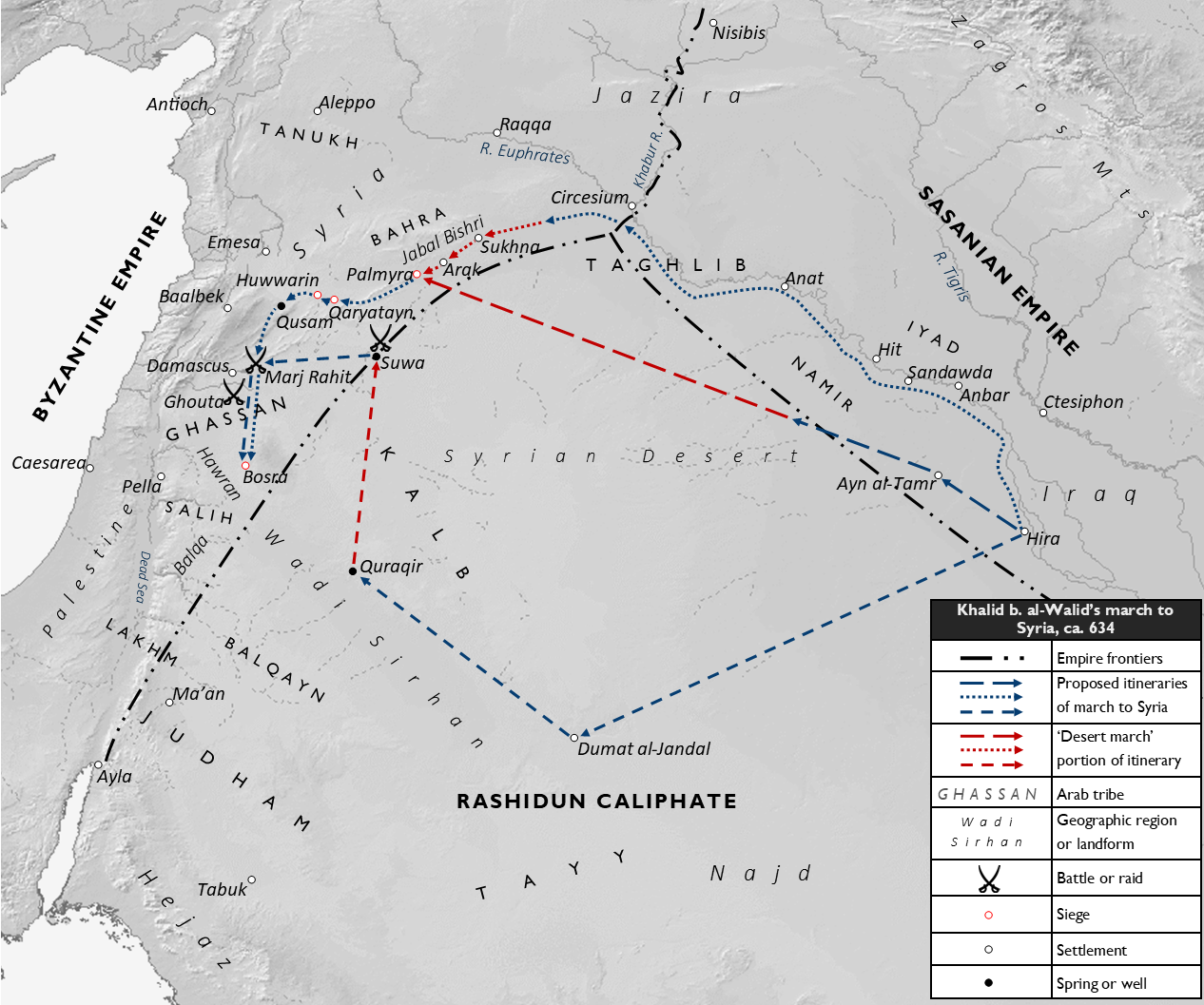

6. Campaigns in Syria (Conquest of the Levant)

All early Islamic accounts agree that Abu Bakr ordered Khalid to leave Iraq for Syria to reinforce existing Muslim forces there. Most accounts indicate that the caliph's order was prompted by requests for reinforcements from Muslim commanders already in Syria. Khalid likely began his march to Syria in early April 634, leaving small Muslim garrisons in the conquered cities of Iraq under the overall military command of al-Muthanna ibn Haritha.

The chronological sequence of events following Khalid's operations in Ayn al-Tamr is inconsistent in historical sources. According to Fred Donner, Khalid undertook two significant operations before his march to Syria, which have often been conflated with events that occurred during the march itself. One operation was against Dumat al-Jandal, and the other targeted the Namir and Taghlib tribes along the western banks of the upper Euphrates valley, extending to the Balikh tributary and the Jabal al-Bishri mountains northeast of Palmyra. It remains unclear which engagement occurred first, but both were part of Muslim efforts to bring the largely nomadic Arab tribes of northern Arabia and the Syrian steppe under Medina's control.

In the Dumat al-Jandal campaign, Khalid was either instructed by Abu Bakr or requested by al-Walid ibn Uqba to reinforce Iyad ibn Ghanm's faltering siege of the oasis town. The town's defenders were supported by their nomadic allies from Byzantine-confederate tribes, including the Ghassanids, Tanukhids, Salihids, Bahra, and Banu Kalb. Khalid traveled from Ayn al-Tamr to Dumat al-Jandal, where the combined Muslim forces decisively defeated the defenders in a pitched battle. Afterward, Khalid executed the town's Kindite leader, Ukaydir, who had defected from Medina following Muhammad's death. However, the Kalbite chief, Wadi'a, was spared due to the intervention of his Tamimite allies within the Muslim camp.

Some historians, such as Michael Jan de Goeje and Leone Caetani, entirely dismiss the notion that Khalid led an expedition to Dumat al-Jandal after his Iraqi campaign. They suggest that the city mentioned in traditional sources might have been another town of the same name near al-Hira. Laura Veccia Vaglieri supports this assessment, finding it "logical" that Khalid would not have made such a significant detour that would delay his mission to join the Muslim armies in Syria. Vaglieri surmises that the oasis was likely conquered by Iyad ibn Ghanm or possibly Amr ibn al-As, who had previously been tasked during the Ridda Wars with suppressing Wadi'a, who had barricaded himself in Dumat al-Jandal. Patricia Crone, who entirely dismisses Khalid's role in Iraq, asserts that Khalid had definitively captured Dumat al-Jandal in the 631 campaign and from there crossed the desert to engage in the Syrian conquest.

6.1. The March to Syria and the Desert March

According to most traditional accounts, Khalid's general march to Syria began from al-Hira, though al-Baladhuri places the starting point at Ayn al-Tamr. The segment of this march known as the 'desert march' occurred at an unclear stage after departing from al-Hira. This phase involved Khalid and his men, numbering between 500 and 800 strong, traversing a vast, waterless stretch of desert from a well called Quraqir for six days and five nights until they reached a water source at Suwa. As his men lacked sufficient waterskins for such a journey, Khalid devised a unique method: he had approximately twenty of his camels consume an increased amount of water and then sealed their mouths to prevent them from eating and spoiling the water in their stomachs. Each day of the march, a number of these camels were slaughtered so his men could drink the water stored within their stomachs. The successful use of camels for water storage and the identification of the water source at Suwa were based on the advice of his guide, Rafi ibn Amr of the Tayy tribe.

Excluding the aforementioned operations in Dumat al-Jandal and the upper Euphrates valley, traditional accounts consistently agree on only two events of Khalid's route to Syria after departing from al-Hira: the desert march between Quraqir and Suwa, and a subsequent raid against the Bahra tribe at or near Suwa, which led to the submission of Palmyra. Otherwise, the narratives diverge in tracing Khalid's exact itinerary. Based on these accounts, Donner summarizes three possible routes taken by Khalid to the vicinity of Damascus: two via Palmyra from the north and one via Dumat al-Jandal from the south. Hugh Kennedy notes that the sources are "equally certain" in their advocacy of their respective itineraries and that there is "simply no knowing which version is correct."

In the first Palmyra-Damascus itinerary, Khalid marches northward along the Euphrates, passing through areas he had previously conquered, to Jabal al-Bishri. From there, he successively moves southwestward through Palmyra, al-Qaryatayn, and Huwwarin before reaching the Damascus area. In this route, the only stretch where a desert march could have occurred is between Jabal al-Bishri and Palmyra, although this area is considerably less than a six-day march and contains several water sources. The second Palmyra-Damascus itinerary is a relatively direct route between al-Hira and Palmyra via Ayn al-Tamr. The desert stretch between Ayn al-Tamr and Palmyra is long enough to support a six-day march and has scarce watering points, but no placenames that can be definitively identified as Quraqir or Suwa. In the Dumat al-Jandal-Damascus route, such placenames exist: Qulban Qurajir, associated with 'Quraqir' along the eastern edge of Wadi Sirhan, and Sab Biyar, identified with Suwa, located about 93 mile (150 km) east of Damascus. The span between these two sites is arid and aligns with the six-day march narrative.

The desert march is the most celebrated episode of Khalid's expedition and in medieval FutuhFutuhArabic ('Islamic conquests') literature in general. Kennedy writes that the desert march "has been enshrined in history and legend. Arab sources marvelled at his [Khalid's] endurance; modern scholars have seen him as a master of strategy." He affirms that it is "certain" Khalid undertook the march, describing it as "a memorable feat of military endurance" and stating that "his arrival in Syria was an important ingredient of the success of Muslim arms there." Moshe Gil calls the march "a feat which has no parallel" and a testament to "Khalid's qualities as an outstanding commander." However, historian Ryan J. Lynch considers Khalid's desert march to be a literary construct by the authors of the Islamic tradition, designed to create a narrative linking the Muslim conquests of Iraq and Syria and to present the conquests as "a well-calculated, singular affair" in line with the authors' alleged polemical motives. Lynch suggests the story, which "would have excited and entertained" Muslim audiences, was built from "fragments of social memory," with inhabitants attributing the conquests of their towns or areas to Khalid to gain prestige by association with the "famous general."

6.2. Early Engagements in Syria

Most traditional accounts state that the first Muslim armies deployed to Syria from Medina at the beginning of 13 AH (early spring 634). The commanders of these armies included Amr ibn al-As, Yazid ibn Abi Sufyan, Shurahbil ibn Hasana, and Abu Ubayda ibn al-Jarrah, though Abu Ubayda may not have deployed to Syria until after Umar's succession to the caliphate in the summer of 634. According to Fred Donner, the traditional sources' dating of the initial deployment to Syria was off by several months, likely occurring in autumn 633, which aligns better with the anonymous Syriac Chronicle of 724 dating the first clash between Muslim and Byzantine armies to February 634. By the time Khalid left Iraq, Muslim armies in Syria had already engaged in skirmishes with local Byzantine garrisons and dominated the southern Syrian countryside, but had not yet captured any urban centers.

Khalid was appointed supreme commander of the Muslim armies in Syria. Accounts from historians like al-Baladhuri, al-Tabari, Ibn A'tham, al-Fasawi, and Ibn Hubaysh al-Asadi state that Abu Bakr appointed Khalid to this position as part of his reassignment from Iraq to Syria, recognizing his military talents and track record. One account in al-Baladhuri, however, attributes Khalid's appointment to a consensus among the commanders already in Syria, though Athamina finds it "inconceivable that a man like [Amr ibn al-As] would agree" to such a decision voluntarily. Upon his accession, Umar may have confirmed Khalid as supreme commander.

Khalid reached the meadow of Marj Rahit north of Damascus after his army's arduous desert trek. He arrived on Easter day, 24 April 634, a precise date noted by most traditional sources that Donner considers likely correct. There, Khalid attacked a group of Ghassanids celebrating Easter, before he or his subordinate commanders raided the Ghouta agricultural belt surrounding Damascus. Afterward, Khalid and the commanders of the earlier Muslim armies, excluding Amr, assembled at Bosra southeast of Damascus. This trading center in the Hauran region had historically supplied nomadic Arab tribes with wheat, oil, and wine, and Muhammad had visited it in his youth. The Byzantines may not have re-established an imperial garrison there after the Sasanian withdrawal in 628, leading to token resistance during the Muslim siege. Bosra capitulated in late May 634, becoming the first major city in Syria to fall to the Muslims.

Khalid and the Muslim commanders then moved west to Palestine to join Amr, serving under him in the Battle of Ajnadayn in July. This was the first major confrontation with the Byzantines, resulting in a decisive Muslim victory. The Byzantines retreated toward Pella ('Fahl' in Arabic), a significant city east of the Jordan River. The Muslims pursued them, achieving another major victory at the Battle of Fahl, though it is unclear whether Amr or Khalid held overall command in this engagement.

6.3. Siege of Damascus

The remnants of the Byzantine forces from Ajnadayn and Fahl retreated north to Damascus, where Byzantine commanders requested imperial reinforcements. Khalid advanced, possibly defeating a Byzantine unit at the Marj al-Suffar plain before besieging the city. Each of the five Muslim commanders was tasked with blocking one of the city gates; Khalid was stationed at Bab Sharqi (the East Gate). A sixth contingent positioned at Barzeh immediately north of Damascus repelled relief troops dispatched by the Byzantine emperor Heraclius (575-641).

Several traditions describe the Muslim capture of Damascus. The most popular narrative, preserved by the Damascus-based historian Ibn Asakir (died 1175), states that Khalid and his men breached the Bab Sharqi gate. Khalid's forces scaled the city's eastern walls, killing the guards and other defenders at Bab Sharqi. Simultaneously, Muslim forces led by Abu Ubayda entered peacefully from the western Bab al-Jabiya gate after negotiations with Damascene notables, led by Mansur ibn Sarjun, a high-ranking city official. The Muslim armies converged in the city center, where capitulation terms were agreed upon. In contrast, al-Baladhuri claims Khalid entered peacefully from Bab Sharqi while Abu Ubayda entered from the west by force. Modern research often questions Abu Ubayda's presence in Syria at the time of the siege; Caetani expresses doubt about these traditions, while Henri Lammens suggests Yazid ibn Abi Sufyan instead of Abu Ubayda.

In the versions of the Syriac author Dionysius of Tel Mahre (died 845) and the Melkite patriarch Eutychius of Alexandria (died 940), the Damascenes, led by Mansur, weary of the siege and convinced of the besiegers' resolve, approached Khalid at Bab Sharqi with an offer to open the gate in exchange for assurances of safety. Khalid accepted and ordered the drafting of a capitulation agreement. While several versions of Khalid's treaty were recorded in early Muslim and Christian sources, they generally concur that the inhabitants' lives, properties, and churches would be safeguarded in return for their payment of the jizya (poll tax). Imperial properties were confiscated by the Muslims. This treaty likely served as a model for capitulation agreements across Syria, Iraq, and Egypt during the early Muslim conquests. Although accounts by al-Waqidi (died 823) and Ibn Ishaq agree that Damascus surrendered in August or September 635, they provide varying timelines for the siege, ranging from four to fourteen months.

6.4. Battle of Yarmouk

In the spring of 636, Khalid strategically withdrew his forces from Damascus to the old Ghassanid capital at Jabiya in the Golan Heights. This was a direct response to the approach of a large Byzantine army dispatched by Emperor Heraclius. The Byzantine force consisted of imperial troops led by Vahan and Theodore Trithyrius, and frontier troops, including Christian Arab light cavalry led by the Ghassanid phylarch Jabala ibn al-Ayham and Armenian auxiliaries commanded by a certain Georgius (referred to as Jaraja by the Arabs). The exact sizes of the opposing forces are debated by modern historians: Fred Donner suggests the Byzantines outnumbered the Muslims four to one, while Walter E. Kaegi states the Byzantines "probably enjoyed numerical superiority" with 15,000 to 20,000 or more troops. John Walter Jandora, however, believes there was likely "near parity in numbers," with the Muslims at 36,000 (including 10,000 from Khalid's army) and the Byzantines at approximately 40,000.

The Byzantine army established its camp at the Ruqqad tributary, west of the Muslim positions at Jabiya. In response, Khalid withdrew his forces, taking up a new position north of the Yarmouk River, near where the Ruqqad meets the Yarmouk. This area offered strategic high ground, access to water sources, critical routes connecting Damascus to the Galilee, and historic Ghassanid pastures. For over a month, the Muslims held this strategic advantage, and on July 23, 636, they defeated the Byzantines in a skirmish outside Jabiya. Jandora asserts that the Byzantine Christian Arab and Armenian auxiliaries deserted or defected before the main battle, though the Byzantine force remained "formidable," with a vanguard of heavy cavalry and a rear guard of infantrymen when they approached the Muslim defensive lines.

Khalid meticulously organized his cavalry into two main groups, positioning each behind the Muslim's right and left infantry wings. This formation was designed to protect his forces from potential envelopment by the Byzantine heavy cavalry. He also stationed an elite squadron of 200 to 300 horsemen to support the center of his defensive line and positioned archers in the Muslim camp near Dayr Ayyub, where they could be most effective against an advancing Byzantine force. The Byzantines' initial assaults on the Muslim's right and left flanks repeatedly failed, but they maintained momentum until the entire Muslim line fell back-or, as contemporary Christian sources suggest, feigned retreat.

The Byzantines pursued the Muslims into their camp, where the Muslims had hobbled their camel herds to create a series of defensive perimeters. These acted as barriers from which the infantry could fight and which Byzantine cavalry found difficult to penetrate. This tactic left the Byzantines vulnerable to Muslim archers, stalled their momentum, and exposed their left flank. Khalid and his cavalry seized this opportunity to pierce the Byzantines' left flank, exploiting the gap between their infantry and cavalry. Khalid enveloped the opposing heavy cavalry on both sides, deliberately leaving an opening that forced the Byzantines to retreat northward, away from their infantry. According to the 9th-century Byzantine historian Theophanes, the Byzantine infantry mutinied under Vahan, possibly due to Theodore's failure to counter the cavalry attack, leading to the infantry's subsequent rout.

Meanwhile, the Byzantine cavalry had withdrawn north to the area between the Ruqqad and Allan tributaries. Khalid immediately dispatched a force to pursue them and prevent their regrouping. He followed this with a nighttime operation in which he seized the Ruqqad bridge, the Byzantines' only viable retreat route. On August 20, the Muslims then assaulted the Byzantine camps, massacring most of the troops, or inducing panic that caused thousands to die in the Yarmouk's ravines as they attempted a westward retreat.

John Walter Jandora credits the Muslim victory at Yarmouk to the cohesion and "superior leadership" of the Muslim army, particularly Khalid's "ingenuity," in stark contrast to the widespread discord within the Byzantine army's ranks and the conventional tactics of Theodore, which Khalid "correctly anticipated." Moshe Gil observes that Khalid's initial withdrawal before Heraclius's army, the evacuation of Damascus, and the counter-movement on the Yarmouk tributaries "are evidence of his excellent organising ability and his skill at manoeuvring on the battlefield." The Byzantine rout at Yarmouk marked the destruction of their last effective army in Syria, immediately securing earlier Muslim gains in Palestine and Transjordan. This victory paved the way for the recapture of Damascus in December (this time by Abu Ubayda) and the conquest of the Beqaa Valley, ultimately leading to the full conquest of the rest of northern Syria. Jandora considers Yarmouk "one of the most important battles of World History," as it ultimately led to Muslim victories that expanded the Caliphate from the Pyrenees mountains to Central Asia.

6.5. Conquest of Northern Syria

After Yarmouk, Abu Ubayda and Khalid proceeded northward from Damascus to Homs (known as Emesa to the Byzantines), besieging the city probably in the winter of 636-637. The siege endured a number of sorties by the Byzantine defenders, and the city capitulated in the spring. Under the surrender terms, taxes were imposed on the inhabitants in exchange for guarantees of protection for their property, churches, water mills, and city walls. A quarter of the church of St. John was designated for Muslim use, and abandoned houses and gardens were confiscated and distributed by Abu Ubayda or Khalid among the Muslim troops and their families. Given its proximity to the desert steppe, Homs was seen as a favorable settlement for Arab tribesmen and became the first city in Syria to acquire a large Muslim population.

Information regarding the subsequent conquests in northern Syria is scarce and partly contradictory. Khalid was dispatched by Abu Ubayda to conquer Qinnasrin (Chalcis to the Byzantines) and nearby Aleppo. In the outskirts of Qinnasrin, Khalid routed a Byzantine force led by a certain Minas. There, Khalid spared the inhabitants after their appeal, claiming they were Arabs forcibly conscripted by the Byzantines. He then besieged the walled town of Qinnasrin, which capitulated in August or September 638. Khalid and Iyad ibn Ghanm subsequently launched the first Muslim raid into Byzantine Anatolia. Khalid made Qinnasrin his headquarters, settling there with his wife, and was appointed Abu Ubayda's deputy governor in Qinnasrin in 638. The campaigns against Homs and Qinnasrin resulted in the conquest of northwestern Syria and prompted Emperor Heraclius to abandon his headquarters at Edessa for Samosata in Anatolia, eventually retreating to the imperial capital of Constantinople. Heraclius abandoned all forts between Antioch and Tarsus to create a buffer zone against Muslim expansion. Umar commented on this, wishing for "a wall of fire between us and the Romans, that would keep them from coming in and us from going out."

Khalid may have participated in the siege of Jerusalem, which capitulated in 637 or 638. According to al-Tabari, he was one of the witnesses to a letter of assurance by Umar to Patriarch Sophronius of Jerusalem, guaranteeing the safety of the city's people and property.

7. Demotion and Later Service

Khalid was retained as supreme commander of the Muslim forces in Syria for a period ranging from six months to two years from the start of Umar's caliphate, depending on the historical source. Modern historians largely agree that Khalid's dismissal from this supreme command likely occurred in the aftermath of the decisive Battle of Yarmouk. Caliph Umar replaced Khalid with Abu Ubayda ibn al-Jarrah, reassigned Khalid's troops to other Muslim commanders, and subordinated Khalid to one of Abu Ubayda's lieutenants. A later order also saw the bulk of Khalid's former troops redeployed to Iraq.

7.1. Dismissal by Umar

Various reasons are cited in early Islamic sources for Khalid's dismissal from supreme command. These include his tendency toward independent decision-making and minimal coordination with the leadership in Medina. Older allegations of moral misconduct resurfaced, particularly his controversial execution of Malik ibn Nuwayra and his subsequent marriage to Malik's widow, which was seen as contravening the traditional Islamic bereavement period. Accusations also arose regarding Khalid's generous distribution of war spoils to members of the tribal nobility and poets, allegedly to the detriment of early Muslim converts who were equally deserving. Furthermore, there was personal animosity between Khalid and Umar, and Umar expressed uneasiness over Khalid's heroic reputation among the Muslims, fearing it could develop into a personality cult where troops would place their trust in Khalid rather than in God.

Modern historians have offered different perspectives on the primary cause of Khalid's dismissal. Michael Jan de Goeje, William Muir, and Andreas Stratos suggest that Umar's personal enmity toward Khalid was a contributing factor. While Muhammad Abdulhayy Shaban acknowledges this enmity, he asserts it did not influence Umar's decision. De Goeje dismisses Khalid's extravagant grants to the tribal nobility-a common practice among early Muslim leaders, including Muhammad-as a significant reason for his removal. Muir, C. H. Becker, Stratos, and Philip K. Hitti have proposed that Khalid was dismissed because the substantial Muslim gains in Syria after Yarmouk necessitated a capable administrator like Abu Ubayda at the helm, rather than a purely military commander.

Khalil Athamina, however, doubts all these stated reasons, arguing that the true cause "must have been vital" given that large parts of Syria remained under Byzantine control and Heraclius had not yet abandoned the province. Athamina contends that Abu Ubayda, "with all his military limitations," would not have been considered "a worthy replacement for Khālid's incomparable talents." He suggests that Medina's lack of a regular standing army, the need to redeploy fighters to other fronts, and the continuing Byzantine threat necessitated establishing a defense structure based on older-established Arab tribes in Syria who had previously served as Byzantine confederates. After Medina's overtures to the leading Ghassanid confederates were rebuffed, relations were established with the Kalb, Judham, and Lakhm tribes. These tribes likely viewed the large numbers of outside Arab tribesmen in Khalid's army-which had swelled from an initial 500-800 men to as high as 10,000, and up to 30,000-40,000 factoring in their families-as a threat to their political and economic power. Athamina concludes that Umar dismissed Khalid and recalled his troops from Syria as an overture to the Kalb and their allies, aiming to integrate them into the nascent Islamic state's defense structure.

According to Sayf ibn Umar, a rumor circulated in 638 that Khalid had lavishly distributed war spoils from his northern Syrian campaigns, including a sum of 10,000 dirhams to the Kindite nobleman al-Ash'ath ibn Qays. Consequently, Umar ordered Abu Ubayda to publicly interrogate Khalid and relieve him from his post, regardless of the interrogation's outcome, also placing Qinnasrin under Abu Ubayda's direct administration. Following his interrogation in Homs, Khalid delivered successive farewell speeches to the troops in Qinnasrin and Homs before being summoned by Umar to Medina. Sayf's account states that Umar sent notice to Muslim garrisons in Syria and Iraq that Khalid was dismissed not due to improprieties, but because the troops had become "captivated by illusions on account of him [Khalid]," and Umar feared they would disproportionately place their trust in Khalid rather than God.

Khalid's sacking did not provoke a public backlash, possibly because the Muslim polity was already aware of Umar's enmity toward Khalid, which prepared them for his dismissal, or due to existing hostility toward the Banu Makhzum in general, stemming from their earlier opposition to Muhammad and the early Muslims. In Ibn Asakir's account, Umar declared at a council of the Muslim army at Jabiya in 638 that Khalid was dismissed for lavishing war spoils on war heroes, tribal nobles, and poets instead of reserving the funds for needy Muslims. No commanders present voiced opposition, except for a Makhzumite who accused Umar of violating the military mandate Muhammad had given to Khalid. According to the Muslim jurist Ibn Shihab al-Zuhri (died 742), before his death in 639, Abu Ubayda appointed Khalid and Iyad ibn Ghanm as his successors. However, Umar confirmed only Iyad as governor of the Homs-Qinnasrin-Jazira district and appointed Yazid ibn Abi Sufyan governor over the rest of Syria, specifically the districts of Damascus, Jordan, and Palestine. This marked the end of Khalid's active military command.

7.2. Service under Abu Ubayda

Despite his demotion from supreme command, Khalid ibn al-Walid continued to serve in a subordinate capacity as a key lieutenant under Abu Ubayda ibn al-Jarrah in the ongoing campaigns in northern Syria. His military contributions remained significant in securing Muslim gains in the region.

Khalid actively participated in the sieges of Homs and Aleppo, and in the Battle of Qinnasrin (Hazir), all occurring between 637 and 638. These engagements collectively hastened the retreat of imperial Byzantine troops from Syria under Emperor Heraclius. His tactical expertise continued to be an asset to the Muslim army, even in his diminished role.

8. Death

Khalid ibn al-Walid died in 642 CE, either in Medina or Homs.

Purported hadiths related about Khalid include Muhammad's urgings to Muslims not to harm Khalid and prophecies that Khalid would face injustices despite his tremendous contributions to Islam. In Islamic literary narratives, Umar reportedly expresses remorse over dismissing Khalid, and the women of Medina are said to have mourned his death en masse. However, Athamina views these accounts as "no more than latter-day expressions of sympathy on the part of subsequent generations for the heroic character of Khalid as portrayed by Islamic tradition."

It is reported that Khalid expressed deep disappointment at the prospect of dying in his bed rather than as a martyr on the battlefield. He lamented, "I have participated in so many battles, seeking to be a martyr. There is no spot on my body, no scar or wound, except from a spear or a sword. And now I must die in my bed like an old camel." In response, a friend reportedly consoled him, saying, "You must understand, O Khalid. When the Messenger of Allah (Muhammad), peace be upon him, gave you the title 'Sword of Allah,' he decreed that you would never lose a battle. If you were killed by an unbeliever, it would mean that the Sword of Allah had been broken by the enemies of Allah; and that should not happen." Umar ibn al-Khattab reportedly wept upon hearing of Khalid's death, saying, "May God have mercy on you, Abu Sulayman (Khalid). What you do now is better than what you have today. Now you are with Allah..." Khalid's tombstone is said to list over 50 battles in which he was undefeated.

9. Legacy and Assessment

Khalid ibn al-Walid is widely regarded by historians as one of the most seasoned and accomplished generals of the early Islamic era. He is credited by early sources as the most effective commander of the Muslim conquests, even after his dismissal from supreme command. Fred Donner describes him as "one of the tactical geniuses of the early Islamic period." Carole Hillenbrand calls him "the most famous of all Arab Muslim generals," while R. Stephen Humphreys refers to him as "perhaps the most famous and brilliant Arab general of the Riddah wars and the early conquests." W. Montgomery Watt credits Khalid "as one of the creators of the Arab empire" due to his "superb generalship, especially in the years immediately following Muhammad's death." His military career is noted for his participation in over 100 battles, including single combat, without a recorded defeat.

9.1. Military Genius and Tactics

Khalid's strategic acumen and tactical innovations were central to the success of the early Muslim conquests. He demonstrated exceptional leadership qualities throughout his military career, including at the Battle of Yarmouk, where his command led to a decisive victory against the Byzantines. His ability to mobilize large, multi-tribal armies over long distances, coupled with his understanding of tribal politics, was a key factor in his success during the Ridda Wars. His use of tactics, such as the strategic retreat and counter-attack at Mu'tah, and the innovative use of camels for water during his desert march to Syria, showcased his ingenuity and endurance.

9.2. Positive Contributions

Khalid's contributions to the expansion of the Islamic empire were immense. He was instrumental in unifying the Arabian Peninsula under the nascent Islamic state during the Ridda Wars. His campaigns in Iraq and Syria were critical in establishing Muslim control over vast territories previously held by the Sasanian Persian and Byzantine Empires. Despite his reputation for ruthlessness, his loyalty and bravery in battle were consistently highlighted, and he served both Muhammad and the early caliphs with dedication, playing a crucial role in securing the foundations of the Caliphate.

9.3. Criticisms and Controversies

While recognizing his military achievements, early Islamic sources present a mixed assessment of Khalid due to certain controversial incidents. His early confrontation with Muhammad at the Battle of Uhud, where he inflicted heavy losses on the Muslims, stands as a notable point of contention. More significantly, his reputation for brutal or disproportionate actions against Arab tribesmen during the Ridda Wars drew criticism. The Banu Jadhima incident, where he attacked the tribe despite their declared conversion to Islam, and the subsequent execution of Malik ibn Nuwayra and immediate marriage to his widow, in contravention of traditional Islamic bereavement customs, remain particularly controversial. These actions led to condemnation from figures like Umar ibn al-Khattab, who pressed for his punishment or dismissal.

Khalid's military fame also made some pious early Muslims, most notably Umar, uneasy. Umar feared that Khalid's heroic reputation could evolve into a personality cult, diverting the troops' loyalty from God to Khalid himself, which was a primary reason for his eventual dismissal from supreme command.

9.4. Influence on Later Military Thought and Culture

Khalid's lasting impact on military history and Arab culture is profound. His reputation as a great general has endured through generations, earning him the title of "Islam's most formidable warrior" during the eras of Muhammad, Abu Bakr, and the conquest of Syria. Streets are named after him across the Arab world, symbolizing his revered status. He is considered a war hero by Sunni Muslims, who laud his unparalleled military achievements and pivotal role in the early expansion of Islam. However, many Shia Muslims view him more critically, often as a war criminal, particularly because of the execution of Malik ibn Nuwayra and his subsequent actions. Despite these differing perspectives, Khalid ibn al-Walid is widely acknowledged as one of the few undefeated commanders in history, a testament to his exceptional strategic and tactical genius.

10. Family and Descendants

Khalid ibn al-Walid's eldest son was named Sulayman, which is why Khalid was known by the kunyakunyaArabic ('paedonymic') Abū SulaymānAbu SulaymanArabic ('father of Sulayman'). Sulayman was reportedly killed during the conquest of Egypt or in Diyarbakir in 639. Khalid was married to Asma, a daughter of Anas ibn Mudrik, who was a prominent chieftain and poet of the Khath'am tribe.

10.1. Sons and Daughters

Among Khalid's known children, his son Abd al-Rahman became a reputable commander in the Arab-Byzantine wars and a close aide to Mu'awiya ibn Abi Sufyan, who later founded the Umayyad Caliphate. Abd al-Rahman served as Mu'awiya's deputy governor of the Homs-Qinnasrin-Jazira district. Another son, Muhajir, was a supporter of Ali ibn Abi Talib, who reigned as caliph from 656 to 661. Muhajir died fighting Mu'awiya's army at the Battle of Siffin in 657 during the First Fitna. Following Abd al-Rahman's death in 666, which was allegedly a result of poisoning ordered by Mu'awiya, Muhajir's son, also named Khalid, attempted to avenge his uncle's death and was arrested. However, Mu'awiya later released him after Khalid paid blood money. Abd al-Rahman's son, also named Khalid, commanded a naval campaign against the Byzantines in 668 or 669. His father, Khalid's father al-Walid, also had other children: sons Hisham, Walid, Ammarah, and Abd al-Sham, and daughters Fakhtah, Fatimah, and possibly Najiyah.

10.2. Later Descendants and Claims

There is no further significant role played by members of Khalid's immediate family in the historical record after his sons and grandsons. His male line of descent reportedly ended around the collapse of the Umayyad Caliphate in around 750 or shortly thereafter when all forty of his male descendants died in a plague in Syria, according to the 11th-century historian Ibn Hazm. Consequently, his family's properties, including his residence and several other houses in Medina, were inherited by Ayyub ibn Salama, a great-grandson of Khalid's brother al-Walid ibn al-Walid. These properties remained in the possession of Ayyub's descendants until at least the late 9th century.

Khalid's house in Medina, a plot of land granted by Muhammad immediately east of the Prophet's Mosque, was completed before Muhammad's death. Though initially small, Muhammad permitted Khalid to build higher than other houses in Medina after he complained about the size. Khalid declared his house a charitable endowment, prohibiting his descendants from selling or transferring its ownership. In the 12th century, Kamal al-Din Muhammad al-Shahrazuri, the chief qadi (Islamic judge) of the Zengid dynasty in Syria, purchased and converted Khalid's house in Medina into a ribatribatArabic ('charitable house' or 'hospice') for men.

Despite the historical consensus regarding the termination of Khalid's direct male line, several later figures or groups claimed descent from him. The family of the 12th-century Arab poet Ibn al-Qaysarani claimed descent from Muhajir ibn Khalid, though the 13th-century historian Ibn Khallikan noted this claim contradicted the consensus of Arabic historians and genealogists. A female line of descent may have survived and was claimed by the 15th-century Sufi religious leader Siraj al-Din Muhammad ibn Ali al-Makhzumi of Homs. Additionally, Kızıl Ahmed Bey, leader of the Isfendiyarids (who ruled a principality in Anatolia until its annexation by the Ottomans), fabricated his dynasty's descent from Khalid. The Sur tribe, under Sher Shah Suri, a 16th-century ruler of India, also claimed descent from Khalid.

11. Commemoration

Since at least the Ayyubid dynasty period in Syria (1182-1260), the city of Homs has gained fame as the location of the purported tomb and mosque of Khalid ibn al-Walid. The 12th-century traveler Ibn Jubayr noted that the tomb contained the graves of both Khalid and his son Abd al-Rahman. Muslim tradition has consistently placed Khalid's tomb in Homs since that time. The original building was altered by the first Ayyubid sultan Saladin (r. 1171-1193) and underwent further changes in the 13th century.

In 1266, the Mamluk sultan Baybars (r. 1260-1277) sought to link his own military achievements with those of Khalid by having an inscription honoring himself carved on Khalid's mausoleum in Homs. During his 17th-century visit to the mausoleum, the Muslim scholar Abd al-Ghani al-Nabulsi agreed that Khalid was buried there but also noted an alternative Islamic tradition that the grave belonged to Mu'awiya's grandson Khalid ibn Yazid. The current mosque structure dates to 1908, when the Ottoman authorities rebuilt it.