1. Biography

Jürgen Habermas's life journey, from his formative years marked by the aftermath of World War II to his distinguished academic career, shaped his profound philosophical and sociological contributions.

1.1. Early Life and Education

Habermas was born on 18 June 1929, in Düsseldorf, Rhine Province, Germany, and grew up in the small town of Gummersbach, near Cologne. He was born with a cleft palate and underwent corrective surgeries during his childhood. Habermas believed that this speech disability influenced his thinking about the profound importance of communication and interdependence, and his emphasis on social equality in discourse.

As a young teenager, Habermas was deeply affected by World War II and the crimes of the Nazi regime, a realization he shared with many of his compatriots after the war. His father, Ernst Habermas, was an executive director of the Cologne Chamber of Industry and Commerce and a member of the Nazi Party from 1933. Habermas himself was a Jungvolkführer, a leader in the German Jungvolk, a section of the Hitler Youth. However, due to his physical condition, he was categorized as a "zealot" under Nazi rule and was prevented from joining the regular Hitler Youth, instead serving as a low-ranking member of an emergency aid team. He later considered this exclusion fortunate, as it spared him from deeper involvement. He was raised in a staunchly Protestant environment, with his grandfather directing a seminary in Gummersbach.

After the German defeat in 1945, Habermas returned to his studies at the gymnasium. The democratic education he received under American occupation significantly influenced his intellectual development. He pursued his academic journey at the University of Göttingen (1949-1950), the University of Zurich (1950-1951), and the University of Bonn (1951-1954). During this period, he specialized in philosophy, history, psychology, German literature, and economics. In 1952, he began contributing book reviews and critiques to newspapers such as the Frankfurter Allgemeine Zeitung. In 1953, he published an essay in the same paper, "Thinking with Heidegger Against Heidegger," critically engaging with Martin Heidegger's philosophy. He earned his doctorate in philosophy from Bonn in 1954 with a dissertation on Schelling's thought, titled Das Absolute und die Geschichte. Von der Zwiespältigkeit in Schellings DenkenGerman ("The Absolute and History: On the Schism in Schelling's Thought"). His dissertation committee included Erich Rothacker and Oskar Becker.

1.2. Academic Career

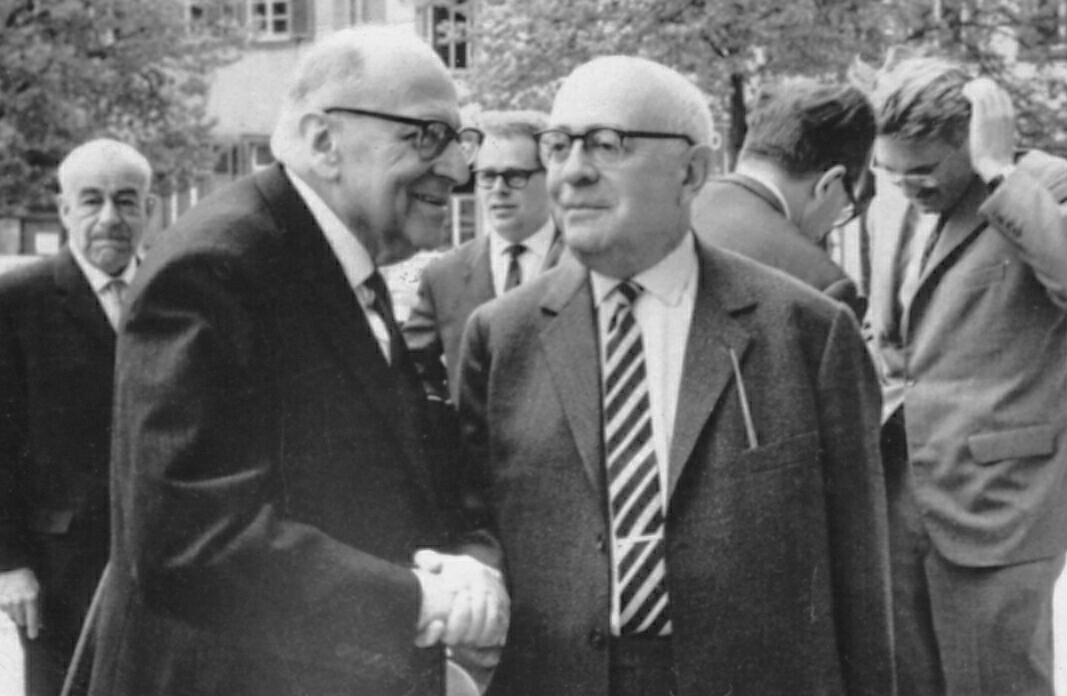

From 1956, Habermas undertook further studies in philosophy and sociology under the critical theorists Max Horkheimer and Theodor W. Adorno at the Goethe University Frankfurt's Institute for Social Research. While working there, he deepened his understanding of Marxism. He participated in a research project on the political attitudes of students at the University of Frankfurt, the findings of which were published in his 1964 book, Student und Politik (Student and Politics).

A rift developed between Habermas and Horkheimer due to Horkheimer's demands for revisions to Habermas's habilitation dissertation, and Habermas's own perception that the Frankfurt School had become overly politically skeptical and disdainful of modern culture. This led to Horkheimer's attempts to exclude Habermas from the Institute, causing Habermas to leave in 1959. He completed his habilitation in political science at the University of Marburg under the Marxist scholar Wolfgang Abendroth. His habilitation thesis, Strukturwandel der Öffentlichkeit. Untersuchungen zu einer Kategorie der bürgerlichen GesellschaftGerman (published in English in 1989 as The Structural Transformation of the Public Sphere: An Inquiry into a Category of Bourgeois Society), was a detailed social history of the development of the bourgeois public sphere. This work gained him significant public attention in Germany upon its publication in 1962.

In 1961, he became a Privatdozent in Marburg. In an unusual academic move for the time, he was offered and accepted a position as an "extraordinary professor" of philosophy at the University of Heidelberg in 1962, largely at the instigation of Hans-Georg Gadamer and Karl Löwith. In 1964, with strong support from Adorno, Habermas returned to Frankfurt to assume Horkheimer's chair in philosophy and sociology. The philosopher Albrecht Wellmer served as his assistant in Frankfurt from 1966 to 1970.

In 1971, Habermas accepted the directorship of the Max Planck Institute for the Study of the Scientific-Technical World in Starnberg, near Munich. He worked there until 1983, two years after the publication of his magnum opus, The Theory of Communicative Action. After a decade of intense research and writing at the Max Planck Institute, during which his philosophical thought matured significantly, he returned to his chair at Frankfurt and the directorship of the Institute for Social Research in 1983. He retired from Frankfurt in 1993, becoming an emeritus professor in 1994.

Since his retirement, Habermas has continued to publish extensively and maintain an active international presence, frequently invited to speak at academic gatherings. He has held positions as a "permanent visiting" professor at Northwestern University in Evanston, Illinois, and as a "Theodor Heuss Professor" at The New School in New York City. In 1984, he was elected a Foreign Honorary Member of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences.

1.3. Intellectual Lineage and Role as Mentor

Habermas was a renowned teacher and mentor, greatly influencing a generation of philosophers and social theorists. His intellectual development was shaped by several key figures. He studied under critical theorists Max Horkheimer and Theodor W. Adorno at the Institute for Social Research and completed his habilitation under the Marxist Wolfgang Abendroth. He was also invited to Heidelberg by Hans-Georg Gadamer and Karl Löwith, indicating their early recognition of his talent.

Among his most prominent students are:

- Herbert Schnädelbach: Pragmatic philosopher and theorist of discourse distinction and rationality.

- Claus Offe: Political sociologist and professor at the Hertie School of Governance in Berlin.

- Johann Arnason: Social philosopher, professor at La Trobe University, and chief editor of the journal Thesis Eleven.

- Hans-Herbert Kögler: Social philosopher and Chair of Philosophy at the University of North Florida.

- Hans Joas: Sociological theorist, professor at the University of Erfurt and at the University of Chicago.

- Klaus Eder: Theorist of societal evolution.

- Axel Honneth: Social philosopher.

- David Rasmussen: Political theorist, professor at Boston College, and chief editor of the journal Philosophy & Social Criticism.

- Konrad Ott: Environmental ethicist.

- Hans-Hermann Hoppe: An anarcho-capitalist philosopher who later rejected much of Habermas's thought.

- Thomas A. McCarthy: American philosopher.

- Jeremy J. Shapiro: Co-creator of mindful inquiry in social research.

- Cristina Lafont: Political philosopher and Harold H. and Virginia Anderson Professor of Philosophy at Northwestern University.

- Zoran Đinđić: The assassinated Serbian prime minister.

Habermas is also the father of Rebekka Habermas (1959-2023), who was a historian of German social and cultural history and a professor of modern history at the University of Göttingen.

2. Philosophy and Social Theory

Habermas has constructed a comprehensive framework of philosophy and social theory, synthesizing insights from numerous intellectual traditions. He is considered the last major figure of the Frankfurt School and is credited with revitalizing critical theory after it appeared to reach a pessimistic impasse with its first generation.

2.1. Intellectual Background and Influences

Habermas's philosophy draws heavily from a wide array of thinkers and schools of thought, integrating them into his unique system. These include:

- German Philosophical Thought**: He engages deeply with the works of Immanuel Kant, Friedrich Schelling, G. W. F. Hegel, Wilhelm Dilthey, Edmund Husserl, and Hans-Georg Gadamer.

- Marxian Tradition**: His work is rooted in the theories of Karl Marx himself, as well as the critical neo-Marxian theory of the Frankfurt School, particularly Max Horkheimer, Theodor W. Adorno, and Herbert Marcuse.

- Sociological Theories**: He incorporates the sociological insights of Max Weber, Émile Durkheim, and George Herbert Mead.

- Linguistic Philosophy and Speech Act Theories**: Habermas critically adapts ideas from Ludwig Wittgenstein, J. L. Austin, P. F. Strawson, Stephen Toulmin, and John Searle.

- Developmental Psychology**: He draws on the developmental psychological theories of Jean Piaget and Lawrence Kohlberg.

- American Pragmatism**: The tradition of Charles Sanders Peirce and John Dewey significantly influences his work.

- Sociological Social Systems Theory**: He engages with and critiques the theories of Talcott Parsons and Niklas Luhmann.

- Neo-Kantian Thought**: His approach also reflects aspects of Neo-Kantianism.

2.2. Theory of Communicative Action

Habermas considers his most significant contribution to be the development of the concept and theory of communicative reason, or communicative rationality. This theory distinguishes itself from traditional rationalism by locating rationality not in the structure of the cosmos or a subject's consciousness, but in the structures of interpersonal linguistic communication. This social theory aims to advance human emancipation while maintaining an inclusive universalist moral framework.

The framework rests on the argument of universal pragmatics, which posits that all speech acts inherently possess a telos (telospurposeGreek, Ancient) - the goal of mutual understanding. Furthermore, human beings possess the communicative competence to achieve such understanding. Habermas constructed this framework by synthesizing:

- The speech-act philosophy of Ludwig Wittgenstein, J. L. Austin, and John Searle.

- George Herbert Mead's sociological theory of the interactional constitution of mind and self.

- The theories of moral development by Jean Piaget and Lawrence Kohlberg.

- The discourse ethics of his Frankfurt colleague and fellow student Karl-Otto Apel.

Habermas's work resonates with the traditions of Kant and the Enlightenment and of democratic socialism, emphasizing the potential for transforming the world into a more humane, just, and egalitarian society through the realization of human potential for reason, partly through discourse ethics. While he has stated that the Enlightenment is an "unfinished project," he argues that it should be corrected and complemented, not discarded. This stance differentiates him from the Frankfurt School and much of postmodernist thought, which he criticizes for what he perceives as excessive pessimism, radicalism, and exaggerations.

Within sociology, Habermas's major contribution was the development of a comprehensive theory of societal evolution and modernization. This theory distinguishes between communicative rationality and rationalization on one hand, and strategic/instrumental rationality and rationalization on the other. He offers a critique from a communicative standpoint of the differentiation-based theory of social systems developed by Niklas Luhmann.

He distinguishes between "work" (instrumental action) and "communication" (mutual understanding). While previous critical theorists viewed rationality primarily as conquest or power, leading to a perceived impasse, Habermas argues that critique can only advance through communicative reason, understood as communicative practice or communicative action. A communicative society is not one that engages in critique through revolution or violence, but through argumentation. He differentiates two types of argumentation: discussion or discourse, and critique. His defense of modernity and civil society has served as a significant philosophical alternative to various forms of poststructuralism. He also provides an influential analysis of late capitalism.

Habermas views the rationalization, humanization, and democratization of society in terms of the institutionalization of rationality inherent in the communicative competence unique to the human species. He contends that communicative competence has evolved, but in contemporary society, it is often suppressed or weakened by the way major domains of social life, such as the market, the state, and organizations, have been dominated by strategic/instrumental rationality, allowing the logic of the system to supplant that of the lifeworld.

2.3. Theory of the Public Sphere

In his seminal work, The Structural Transformation of the Public Sphere, Habermas argues that prior to the 18th century, European culture was largely dominated by a "representational" culture. In this culture, power was displayed through symbols and spectacles, aiming to impress and overwhelm subjects. For example, Louis XIV's Palace of Versailles was designed to embody the grandeur of the French state and its monarch, overpowering visitors' senses. Habermas links "representational" culture to the feudal stage of development, positing that the emergence of capitalism marked the appearance of ÖffentlichkeitGerman (the public sphere).

Within the culture characterized by ÖffentlichkeitGerman, a public space emerged, independent of state control, where individuals could freely exchange views and knowledge. Habermas identifies the growth of newspapers, literary journals, reading clubs, Masonic lodges, and coffeehouses in 18th-century Europe as key elements in the gradual shift from "representational" culture to ÖffentlichkeitGerman culture. The essential characteristic of this public sphere culture was its "critical" nature. Unlike "representational" culture, which was one-sided, the ÖffentlichkeitGerman fostered dialogue, with individuals engaging in conversations or exchanging views through print media. He notes that the public sphere first emerged in Britain around 1700, given its more liberal environment, and then spread across Continental Europe throughout the 18th century. Habermas suggests that the French Revolution was largely a consequence of the collapse of "representational" culture and its replacement by the ÖffentlichkeitGerman.

Habermas posited that several factors contributed to the eventual decay of the public sphere. These included the rise of a commercial mass media, which transformed the critical public into a passive consumer public, and the growth of the welfare state, which integrated the state and society so thoroughly that the public sphere was diminished. The public sphere also became a battleground for self-interested groups vying for state resources, rather than a space for fostering public-minded rational consensus. His most recognized work, The Theory of Communicative Action (1981), criticizes the modernization process as an inflexible direction driven by economic and administrative rationalization. He illustrates how formal systems increasingly penetrate everyday life, paralleling the development of the welfare state, corporate capitalism, and mass consumption. These reinforcing trends rationalize public life, leading to the disenfranchisement of citizens as political parties and interest groups become rationalized and representative democracy replaces participatory democracy. Consequently, the boundaries between public and private, the individual and society, and the system and the lifeworld erode. He argues that a democratic public life cannot flourish where matters of public importance are not openly discussed by citizens. An "ideal speech situation" requires participants to have equal capacities for discourse and social equality, with their words free from ideology or other distortions. In this version of the consensus theory of truth, Habermas asserts that truth is what would be agreed upon in an ideal speech situation.

Despite these challenges, Habermas expresses optimism about the potential for the revival of the public sphere. He envisions a future where the representative democracy-reliant nation-state is superseded by a deliberative democracy-reliant political organism founded on the equal rights and obligations of citizens. In such a direct democracy-driven system, an active public sphere is crucial for debates on public matters and as a mechanism for these discussions to influence the decision-making process.

In his view, the public sphere is a democratic space or a medium for social discourse, where citizens can discursively articulate their opinions, interests, and needs. It is an essential condition for democracy, a place where citizens can communicate their political concerns. Furthermore, the public sphere serves as a platform where citizens can freely express their stances and arguments towards the state or government. The public sphere is not merely a physical space, institution, or legal organization; rather, it is the communication among citizens itself. It must be free, open, transparent, and autonomous, without government intervention, and readily accessible to all. Through this public sphere, the collective solidarity of citizens can be forged to counter the forces of the market/capitalism and political machines.

Habermas categorizes the public sphere, where social actors build their public spaces, into various aspects:

- Pluralities: This includes families, informal groups, and voluntary organizations.

- Publicity: Encompassing mass media and cultural institutions.

- Privacy: The realm of individual and moral development.

- Legality: Referring to general legal structures and fundamental rights.

This implies that there is not just one public sphere but many within society. He argues that the public sphere cannot be confined; it exists wherever people gather to discuss relevant topics. Moreover, the public sphere should not be bound by market or political interests, hence its unbounded nature.

2.4. Critical Theory and Modernity

Habermas approaches critical theory as a successor to the Frankfurt School, seeking to overcome the pessimism he perceived in their work, which he believed led to a theoretical impasse. For Habermas, critical theory is not merely a scientific theory in the conventional academic sense, but rather a methodology operating in a dialectical tension between philosophy and social science. Unlike positivistic approaches that focus solely on objective facts, critical theory aims to penetrate social realities to uncover transcendental conditions that transcend empirical data. It is, in essence, a critique of ideology, intending to expose ideological distortions and irrationalism that suppress human freedom and clear thought.

Habermas emphasizes that the Enlightenment, despite its failures in the 20th century, is an "unfinished project" that should be corrected and complemented rather than discarded. He asserts that genuine emancipation involves not merely the elimination of poverty but also the freedom of discussion and dialogue, which he believes can only be achieved through rational argumentation and enlightenment. He maintains his commitment to human rationality, arguing that problems in modern civilization stem not from inherent flaws in reason itself, but from its insufficient realization.

Habermas offered early criticisms of postmodernism in his 1981 essay, "Modernity versus Postmodernity," which gained widespread recognition. He raised the question of whether, given the failures of the 20th century, humanity should "try to hold on to the intentions of the Enlightenment, feeble as they may be, or should we declare the entire project of modernity a lost cause?" He refuses to abandon the possibility of a rational, "scientific" understanding of the lifeworld. His main criticisms of postmodernism include:

- Their ambiguity regarding whether they are producing serious theory or literature.

- Their animation by normative sentiments, the nature of which remains concealed from the reader.

- Their adoption of a totalizing perspective that fails "to differentiate phenomena and practices that occur within modern society."

- Their tendency to ignore everyday life and its practices, which Habermas considers absolutely central.

While influenced by Marxism, Habermas also critically reinterpreted it. He sided with commentators like Hannah Arendt who raised concerns about the limitations of totalitarian perspectives often associated with Marx's over-estimation of the emancipatory potential of the forces of production, expanding this critique in his writings on functional reductionism within the lifeworld in Lifeworld and System: A Critique of Functionalist Reason. Habermas argued that what refuted Marx and his theory of class struggle was the "pacification of class conflict" by the welfare state, which developed in the West after 1945 due to "a reformist relying on the instruments of Keynesian economics". However, Italian philosopher and historian Domenico Losurdo criticized this stance, noting that Habermas's claims lacked the crucial question of whether the welfare state emerged from an inherent capitalist tendency or from political and social mobilization by subaltern classes, ultimately ignoring the precariousness and progressive dismantlement of the welfare state. Habermas also controversially argued that totalitarian behavior could manifest regardless of ideological alignment, coining the term "left fascism" to criticize radical student movements of the 1960s, suggesting that violence and anarchy can appear in any extremist movement, regardless of its proclaimed political leanings.

2.5. Reconstructive Science

Habermas introduces the concept of "reconstructive science" with a dual purpose: to position a "general theory of society" as a bridge between philosophy and social science, and to re-establish the connection between "great theorization" and "empirical research."

The model of "rational reconstructions" serves as the central theme for inquiries into the "structures" of the lifeworld (encompassing "culture," "society," and "personality") and their respective "functions" (cultural reproduction, social integration, and socialization). To achieve this, it is essential to consider the dialectics between the "symbolic representation" of "structures subordinated to all worlds of life" ("internal relationships") and the "material reproduction" of social systems in their entirety ("external relationships" between social systems and their environment).

This model finds its primary application in the "theory of social evolution." It begins with the reconstruction of the necessary conditions for a phylogeny of socio-cultural life forms (termed "hominization") and extends to an analysis of the development of "social formations," which Habermas categorizes into primitive, traditional, modern, and contemporary stages.

The paper attempts, first, to formalize Habermas's "reconstruction of the logic of development" model for "social formations," distinguished by the differentiation between the lifeworld and social systems (and within them, by the "rationalization of the lifeworld" and the "growth in complexity of the social systems"). Second, it seeks to offer methodological clarifications regarding the "explanation of the dynamics" of "historical processes," particularly concerning the "theoretical meaning" of propositions within evolutionary theory. While Habermas believes that "ex-post rational reconstructions" and "system/environment models" cannot fully apply to historiography, they undeniably function as general premises within the argumentative structure of "historical explanation."

3. Key Debates and Public Engagement

Jürgen Habermas is renowned not only as a scholar but also as an influential public intellectual, actively participating in significant academic debates and engaging with contemporary political and social issues.

3.1. Debates with Major Philosophers

Throughout his career, Habermas engaged in crucial philosophical dialogues that shaped his and others' thought.

3.1.1. Positivism Dispute

The positivism dispute was a significant political-philosophical debate in Germany from 1961 to 1969, primarily concerning the methodology of the social sciences. It involved the critical rationalists, notably Karl Popper and Hans Albert, on one side, and the Frankfurt School, represented by Theodor W. Adorno and Jürgen Habermas, on the other.

3.1.2. Habermas and Gadamer

A controversy emerged between Habermas and Hans-Georg Gadamer regarding the limits of hermeneutics. Following the publication of Gadamer's magnum opus, Truth and Method (1960), the two engaged in a debate over the possibility of transcending history and culture to achieve a truly objective position for societal critique. While Gadamer had supported Habermas early in his career, a philosophical disagreement arose in the 1970s. Habermas argued that Gadamer's emphasis on tradition and prejudice obscured the ideological operation of power, accusing him of adopting a dogmatic stance toward tradition that hindered critical reflection on the sources of ideological distortion. Gadamer countered that rejecting the universal nature of hermeneutics was the more dogmatic position, as it implied that the subject could liberate itself from the past.

3.1.3. Habermas and Foucault

A notable dispute exists regarding whether Michel Foucault's ideas of "power analytics" and "genealogy" or Jürgen Habermas's concepts of "communicative rationality" and "discourse ethics" offer a superior critique of the nature of power in society. This debate critically compares and evaluates their central ideas as they pertain to questions of power, reason, ethics, modernity, democracy, civil society, and social action.

3.1.4. Habermas and Apel

Both Habermas and Karl-Otto Apel advocate for a postmetaphysical, universal moral theory, yet they diverge on the nature and justification of this principle. Habermas disagrees with Apel's assertion that the principle functions as a transcendental condition of human activity, while Apel insists it does. Each criticizes the other's position: Habermas contends that Apel is overly preoccupied with transcendental conditions, whereas Apel argues that Habermas insufficiently values critical discourse.

3.1.5. Habermas and Rawls

The Habermas-Rawls debate centers on how to approach political philosophy under conditions of cultural pluralism, especially when the goal is to uncover the normative foundations of a modern liberal democracy. Habermas argues that John Rawls's view is inconsistent with the idea of popular sovereignty. Conversely, Rawls contends that political legitimacy is solely a matter of sound moral reasoning or that democratic will formation has been unduly diminished in Habermas's theory.

3.1.6. Habermas and Derrida

Jürgen Habermas and Jacques Derrida engaged in a series of intellectual exchanges that began in the 1980s and evolved into a mutual understanding and friendship by the late 1990s, lasting until Derrida's death in 2004. Their initial contact occurred when Habermas invited Derrida to speak at the University of Frankfurt in 1984. The following year, Habermas published "Beyond a Temporalized Philosophy of Origins: Derrida" in The Philosophical Discourse of Modernity, in which he argued that Derrida's method was insufficient to provide a foundation for social critique. Derrida, referencing Habermas as an example, retorted that "those who have accused me of reducing philosophy to literature or logic to rhetoric... have visibly and carefully avoided reading me." After Derrida's final rebuttal in 1989, their direct academic dispute ceased, although, as Derrida noted, groups within academia continued a "war" in which the philosophers themselves did not personally or directly participate.

By the late 1990s, Habermas approached Derrida at a party at an American university where both were lecturing, leading to a dinner meeting in Paris. Subsequently, they collaborated on many joint projects. In 2000, they held a joint seminar at the University of Frankfurt addressing problems in philosophy, law, ethics, and politics. In December 2000, Habermas delivered a lecture entitled "How to answer the ethical question?" at the Judeities. Questions for Jacques Derrida conference in Paris, organized by Joseph Cohen and Raphael Zagury-Orly. Following Habermas's lecture, both thinkers engaged in a heated debate on Heidegger and the possibility of ethics.

In the aftermath of the 11 September attacks, Derrida and Habermas articulated their individual perspectives on 9/11 and the War on Terror in Giovanna Borradori's Philosophy in a Time of Terror: Dialogues with Jürgen Habermas and Jacques Derrida. In early 2003, both Habermas and Derrida actively opposed the impending Iraq War. In a manifesto that later became the book Old Europe, New Europe, Core Europe, they called for a stronger unification of European Union member states to create a power capable of countering American foreign policy. Derrida's foreword to the book expressed his complete endorsement of Habermas's February 2003 declaration, "February 15, or, What Binds Europeans Together: Plea for a Common Foreign Policy, Beginning in Core Europe," which was a direct response to the George W. Bush administration's demands for European support in the upcoming Iraq War.

3.2. Historians' Dispute (Historikerstreit)

Habermas's role as a public intellectual was famously demonstrated in the Historikerstreit ("Historians' Dispute") of the 1980s. He used the popular press to critically engage with German historians such as Ernst Nolte, Michael Stürmer, Klaus Hildebrand, and Andreas Hillgruber. Habermas first articulated his views in Die Zeit on 11 July 1986, in a feuilleton (a cultural opinion essay) titled "A Kind of Settlement of Damages."

Habermas accused Nolte, Hildebrand, Stürmer, and Hillgruber of "apologistic" history writing concerning the Nazi era, arguing that they sought to "close Germany's opening to the West" that had existed since 1945. He contended that these historians attempted to detach Nazi rule and the Holocaust from the mainstream of German history, explain away Nazism as a reaction to Bolshevism, and partially rehabilitate the reputation of the Wehrmacht (German Army) during World War II. Habermas asserted that Stürmer was trying to create a "vicarious religion" in German history, which, along with Hillgruber's work glorifying the final days of the German Army on the Eastern Front, was intended to serve as a "kind of NATO philosophy colored with German nationalism." He criticized Hillgruber's statement regarding Adolf Hitler's intention to exterminate Jews, questioning the historian's perspective.

Habermas famously declared: "The unconditional opening of the Federal Republic to the political culture of the West is the greatest intellectual achievement of our postwar period; my generation should be especially proud of this. This event cannot and should not be stabilized by a kind of NATO philosophy colored with German nationalism. The opening of the Federal Republic has been achieved precisely by overcoming the ideology of Central Europe that our revisionists are trying to warm up for us with their geopolitical drumbeat about 'the old geographically central position of the Germans in Europe' (Stürmer) and 'the reconstruction of the destroyed European Center' (Hillgruber). The only patriotism that will not estrange us from the West is a constitutional patriotism."

The Historikerstreit was a multifaceted debate. Habermas himself faced criticism from scholars including Joachim Fest, Hagen Schulze, Horst Möller, Imanuel Geiss, and Klaus Hildebrand. Conversely, he received support from historians such as Martin Broszat, Eberhard Jäckel, Hans Mommsen, and Hans-Ulrich Wehler.

3.3. Views on Political and Social Issues

Habermas has consistently engaged with a wide range of contemporary political and social challenges, offering critical perspectives and advocating for democratic and humanitarian principles.

3.3.1. Stance on Religion

Habermas's views on the social role of religion have evolved over time. Analyst Phillippe Portier identifies three phases:

- 1980s**: An early Marxist-influenced period where he argued against religion, viewing it as an "alienating reality" and a "control tool."

- Mid-1980s to early 21st century**: He largely ceased discussing religion, relegating it to matters of private life as a secular commentator.

- Early 21st century onward**: He began to recognize a positive social role for religion, particularly in the context of multiculturalism and immigration, which he saw as strengthening religious forces.

In a 1999 interview, Habermas stated: "For the normative self-understanding of modernity, Christianity has functioned as more than just a precursor or catalyst. Universalistic egalitarianism, from which sprang the ideals of freedom and a collective life in solidarity, the autonomous conduct of life and emancipation, the individual morality of conscience, human rights and democracy, is the direct legacy of the Judaic ethic of justice and the Christian ethic of love. This legacy, substantially unchanged, has been the object of a continual critical reappropriation and reinterpretation. Up to this very day there is no alternative to it. And in light of the current challenges of a post-national constellation, we must draw sustenance now, as in the past, from this substance. Everything else is idle postmodern talk." This statement, however, has been frequently misquoted, often simplified to suggest that Christianity is the sole foundation of Western civilization's benchmarks.

The original German (from the Habermas Forum website) of the disputed quotation is:

Das Christentum ist für das normative Selbstverständnis der Moderne nicht nur eine Vorläufergestalt oder ein Katalysator gewesen. Der egalitäre Universalismus, aus dem die Ideen von Freiheit und solidarischem Zusammenleben, von autonomer Lebensführung und Emanzipation, von individueller Gewissensmoral, Menschenrechten und Demokratie entsprungen sind, ist unmittelbar ein Erbe der jüdischen Gerechtigkeits- und der christlichen Liebesethik. In der Substanz unverändert, ist dieses Erbe immer wieder kritisch angeeignet und neu interpretiert worden. Dazu gibt es bis heute keine Alternative. Auch angesichts der aktuellen Herausforderungen einer postnationalen Konstellation zehren wir nach wie vor von dieser Substanz. Alles andere ist postmodernes Gerede.

This statement has been misquoted in a number of articles and books, where Habermas instead is quoted for saying:

Christianity, and nothing else, is the ultimate foundation of liberty, conscience, human rights, and democracy, the benchmarks of Western civilization. To this day, we have no other options. We continue to nourish ourselves from this source. Everything else is postmodern chatter.

In his 2005 book Zwischen Naturalismus und Religion (Between Naturalism and Religion), Habermas stated that the forces of religious strength, as a result of multiculturalism and immigration, are stronger than in previous decades, and, therefore, there is a need of tolerance which must be understood as a two-way street: secular people need to tolerate the role of religious people in the public square and vice versa.

In early 2007, Ignatius Press published The Dialectics of Secularization, a dialogue between Habermas and the then Prefect of the Congregation for the Doctrine of the Faith Joseph Ratzinger (elected as Pope Benedict XVI in 2005). The dialogue took place on 14 January 2004 after an invitation to both thinkers by the Catholic Academy of Bavaria in Munich. It addressed contemporary questions such as:

- Is a public culture of reason and ordered liberty possible in our post-metaphysical age?

- Is philosophy permanently cut adrift from its grounding in being and anthropology?

- Does this decline of rationality signal an opportunity or a deep crisis for religion itself?

In this debate a shift of Habermas became evident-in particular, his rethinking of the public role of religion. Habermas stated that he wrote as a "methodological atheist," which means that when doing philosophy or social science, he presumed nothing about particular religious beliefs. Yet while writing from this perspective his evolving position towards the role of religion in society led him to some challenging questions, and as a result conceding some ground in his dialogue with the future Pope, that would seem to have consequences which further complicated the positions he holds about a communicative rational solution to the problems of modernity. Habermas believes that even for self-identified liberal thinkers, "to exclude religious voices from the public square is highly illiberal."

In addition, Habermas has popularized the concept of "post-secular" society, to refer to current times in which the idea of modernity is perceived as unsuccessful and at times, morally failed, so that, rather than a stratification or separation, a new peaceful dialogue and coexistence between faith and reason must be sought in order to learn mutually.

3.3.2. Stance on Socialism

Habermas has sided with other 20th-century commentators on Marx such as Hannah Arendt who have indicated concerns with the limits of totalitarian perspectives often associated with Marx's over-estimation of the emancipatory potential of the forces of production. Arendt had presented this in her book The Origins of Totalitarianism and Habermas extends this critique in his writings on functional reductionism in the life-world in his work, Lifeworld and System: A Critique of Functionalist Reason. As Habermas states:

... traditional Marxist analysis ... today, when we use the means of the critique of political economy ... can no longer make clear predictions: for that, one would still have to assume the autonomy of a self-reproducing economic system. I do not believe in such an autonomy. Precisely for this reason, the laws governing the economic system are no longer identical to the ones Marx analyzed. Of course, this does not mean that it would be wrong to analyze the mechanism which drives the economic system; but in order for the orthodox version of such an analysis to be valid, the influence of the political system would have to be ignored.

Habermas reiterated the positions that what refuted Marx and his theory of class struggle was the "pacification of class conflict" by the welfare state, which had developed in the West "since 1945", thanks to "a reformist relying on the instruments of Keynesian economics". Italian philosopher and historian Domenico Losurdo criticised the main point of these claims as "marked by the absence of a question that should be obvious:- Was the advent of the welfare state the inevitable result of a tendency inherent in capitalism? Or was it the result of political and social mobilization by the subaltern classes-in the final analysis, of a class struggle? Had the German philosopher posed this question, perhaps he would have avoided assuming the permanence of the welfare state, whose precariousness and progressive dismantlement are now obvious to everyone".

3.3.3. Stance on Wars

Habermas has taken clear public positions on major international conflicts:

- In 1999, he addressed the Kosovo War, defending NATO's intervention in an article for Die Zeit, which generated controversy.

- In 2002, he publicly argued that the United States should not go to war in Iraq.

- On 13 November 2023, Habermas issued a statement supporting Israel's military response to the Hamas-led attack on Israel, rejecting the term genocide in reference to Israel's actions in the Gaza Strip.

3.3.4. Views on the European Union

During the European debt crisis, Habermas voiced criticism of Angela Merkel's leadership in Europe. In 2013, he engaged in a public debate with Wolfgang Streeck, who argued that the kind of European federalism advocated by Habermas was a root cause of the continent's crisis.

In the aftermath of the 9/11 attacks and in opposition to the impending Iraq War, Habermas, along with Jacques Derrida, called for a tighter unification of the states of the European Union. In their jointly supported manifesto that became the book Old Europe, New Europe, Core Europe, they advocated for the creation of a unified European power capable of opposing American foreign policy. This call, articulated notably in Habermas's February 2003 declaration "February 15, or, What Binds Europeans Together: Plea for a Common Foreign Policy, Beginning in Core Europe," was a direct response to the George W. Bush administration's demands for European support in the upcoming Iraq War.

3.3.5. Relationship with the Student Movement

During the radical "New Left" student movements of the 1960s and 1970s in West Germany, Habermas initially gained popularity and was even regarded as an ideologue by some. However, his relationship with these movements soon soured. He became increasingly critical of what he saw as the students' resort to anarchic or violent actions, famously condemning their excesses as a "false revolution," "counterproductive," and even labeling their methods as "left fascism" in his 1969 book, Protestbewegung und Hochschulreform (Opposition Movement and University Reform).

This strong criticism made Habermas a target of the radical student activists, who denounced him as a "bourgeois reactionary intellectual." The conflict with the student movement eventually led him to leave the University of Frankfurt in 1971 to work at the Max Planck Institute in Starnberg. The controversy also highlighted the perceived narrow-mindedness of some left-wing and activist factions who were unwilling to accept internal criticism.

Beyond the German context, Habermas also demonstrated concern for human rights and freedom of expression in South Korea. He critically addressed the South Korean government's perceived violence and disrespect for freedom of expression and freedom of thought, particularly in cases involving critical figures like Kim Ji-ha and Song Du-yul. In one notable instance, during Song Du-yul's imprisonment in 2003 on charges of violating the National Security Act, Habermas mistakenly believed Song was to receive the "Ahn Jung-geun Peace Prize" while on temporary release. Reportedly, Habermas advised Song to seek refuge at the German embassy, demonstrating his commitment to protecting intellectual freedom.

4. Awards and Honors

Jürgen Habermas has received numerous prestigious academic and cultural awards throughout his distinguished career, recognizing his profound contributions to philosophy and social theory.

- 1974: Hegel Prize

- 1976: Sigmund Freud Prize

- 1980: Theodor W. Adorno Award

- 1985: Geschwister-Scholl-Preis for his work, Die neue Unübersichtlichkeit

- 1986: Gottfried Wilhelm Leibniz Prize, the highest honor awarded in German research.

- 1987: The Sonning Prize, awarded biennially for outstanding contributions to European culture.

- 1995: Karl Jaspers Prize

- 1999: Theodor Heuss Prize

- 2001: Peace Prize of the German Book Trade

- 2003: Prince of Asturias Award in Social Sciences

- 2004: Kyoto Prize in Arts and Philosophy, receiving 50.00 M JPY.

- 2005: Holberg International Memorial Prize, receiving approximately 520.00 K EUR.

- 2006: Bruno Kreisky Award

- 2008: European Prize for Political Culture (Hans Ringier Foundation) at the Locarno Film Festival, receiving 50.00 K EUR.

- 2010: Ulysses Medal, University College Dublin.

- 2011: Viktor-Frankl-Preis

- 2012: Georg-August-Zinn-Preis

- 2012: Heinrich Heine Prize

- 2012: Cultural Honor Prize of the City of Munich

- 2013: Erasmus Prize

- 2015: Kluge Prize

- 2021: Declined the Sheikh Zayed Book Award, citing the United Arab Emirates' political system as a repressive non-democracy.

- 2022: Dialectic Medal

- 2022: Pour le Mérite

- 2024: Johan Skytte Prize in Political Science

5. Major Works

Jürgen Habermas has authored and co-authored a prolific body of work that has profoundly shaped contemporary philosophy and social theory. Below is a chronological list of his most significant academic books and essays:

- Das Absolute und die Geschichte. Von der Zwiespältigkeit in Schellings Denken (The Absolute and History: On the Schism in Schelling's Thought) (1954): His doctoral dissertation, analyzing Schelling's philosophy.

- Student und Politik (Student and Politics) (1961): Co-authored, this sociological investigation examined the political consciousness of students in Frankfurt.

- The Structural Transformation of the Public Sphere (1962): His habilitation thesis, it is a detailed social history of the development of the bourgeois public sphere from the 18th century to its transformation by mass media and commercialization. It explores how public reason emerged and later declined.

- Theory and Practice (1963): A collection of essays exploring the relationship between philosophical theory and social and political practice.

- On the Logic of the Social Sciences (1967): A methodological reflection on the unique nature of social scientific inquiry.

- Toward a Rational Society (1968): Explores the potential for rationalization in modern societies and challenges to this process.

- Technik und Wissenschaft als "Ideologie" (Technology and Science as "Ideology") (1968): Analyzes how scientific and technical progress can become an ideology, obscuring underlying power relations.

- Knowledge and Human Interests (1971, German 1968): Examines the link between different forms of knowledge and fundamental human interests, distinguishing between technical, practical, and emancipatory interests.

- Theorie der Gesellschaft oder Sozialtechnologie. Was leistet die Systemforschung? (Theory of Society or Social Technology: What Does System Research Achieve?) (1971): Co-authored with Niklas Luhmann, this book initiated a major debate between Habermas's critical theory and Luhmann's systems theory.

- Philosophisch-politische Profile (Philosophical-Political Profiles) (1971): A collection of essays on contemporary philosophers and political thinkers.

- Kultur und Kritik (Culture and Critique) (1973): A collection of scattered essays on culture and critique.

- Legitimation Crisis (1975): Analyzes how late capitalism faces crises of legitimation due to inherent contradictions between economic, political, and cultural systems.

- Communication and the Evolution of Society (1976): Explores the role of communication in societal evolution.

- On the Pragmatics of Social Interaction (1976).

- Zur Rekonstruktion des Historischen Materialismus (Toward the Reconstruction of Historical Materialism) (1976): An attempt to reconstruct and update historical materialism in light of contemporary social theory.

- Politik, Kunst, Religion. Essays über zeitgenössische Philosophen. (Politics, Art, Religion: Essays on Contemporary Philosophers) (1978).

- The Theory of Communicative Action (1981): Considered his magnum opus, this two-volume work develops the concept of communicative rationality as a means to achieve mutual understanding and social integration, offering a critique of modernization driven by instrumental rationality.

- Kleine politische Schriften I-IV (Small Political Writings I-IV) (1981): A collection of shorter political essays.

- Moral Consciousness and Communicative Action (1983): Explores the relationship between moral development, universal ethics, and communicative rationality.

- Vorstudien und Ergänzungen zur Theorie des kommunikativen Handelns (Preliminary Studies and Supplements to the Theory of Communicative Action) (1984).

- Die neue Unübersichtlichkeit. Kleine Politische Schriften V (The New Obscurity: Small Political Writings V) (1985): Addresses the crisis of the welfare state and the complexity of modern society.

- The Philosophical Discourse of Modernity (1985): A critical engagement with postmodernist thought, particularly focusing on the works of French philosophers like Jacques Derrida and Michel Foucault.

- Eine Art Schadensabwicklung. Kleine Politische Schriften VI (A Kind of Settlement of Damages: Small Political Writings VI) (1987): Contains his interventions in the Historians' Dispute.

- Nachmetaphysisches Denken. Philosophische Aufsätze (Postmetaphysical Thinking: Philosophical Essays) (1988): Explores the possibility of philosophy beyond traditional metaphysics.

- Die nachholende Revolution. Kleine politische Schriften VII (The Catching-Up Revolution: Small Political Writings VII) (1990): Reflects on German reunification and the challenges of post-communist transformation.

- Die Moderne - Ein unvollendetes Projekt. Philosophisch-politische Aufsätze (Modernity - An Unfinished Project: Philosophical-Political Essays) (1990): Further develops his idea that modernity is a project of emancipation that needs to be completed.

- Erläuterungen zur Diskursethik (Justification and Application: Remarks on Discourse Ethics) (1991): Further elaborates on his ethical theory based on communicative action.

- Texte und Kontexte (Texts and Contexts) (1991).

- Vergangenheit als Zukunft? Das alte Deutschland im neuen Europa? Ein Gespräch mit Michael Haller (Past as Future? The Old Germany in the New Europe? A Conversation with Michael Haller) (1991).

- Faktizität und Geltung. Beiträge zur Diskurstheorie des Rechts und des demokratischen Rechtsstaates (Between Facts and Norms: Contributions to a Discourse Theory of Law and Democracy) (1992): His comprehensive work on law and democracy, proposing a discourse-theoretical understanding of the relationship between legal facts and normative validity.

- On the Pragmatics of Communication (1992).

- Die Normalität einer Berliner Republik. Kleine Politische Schriften VIII (The Normality of a Berlin Republic: Small Political Writings VIII) (1995).

- The Inclusion of the Other (1996): Essays on political theory, focusing on issues of pluralism, diversity, and the inclusion of marginalized voices.

- Vom sinnlichen Eindruck zum symbolischen Ausdruck. Philosophische Essays (From Sensual Impression to Symbolic Expression: Philosophical Essays) (1997).

- A Berlin Republic (1997): A collection of interviews with Habermas, reflecting on contemporary German society and politics.

- The Postnational Constellation (1998): Examines the challenges to the nation-state in a globalized world.

- Religion and Rationality: Essays on Reason, God, and Modernity (1998).

- Truth and Justification (1998): A collection of philosophical essays discussing truth, justification, and realism.

- Zeit der Übergänge. Kleine Politische Schriften IX (Time of Transitions: Small Political Writings IX) (2001).

- Die Zukunft der menschlichen Natur. Auf dem Weg zu einer liberalen Eugenik? (The Future of Human Nature: On the Way to a Liberal Eugenics?) (2003): Discusses the ethical implications of genetic engineering and human enhancement.

- Old Europe, New Europe, Core Europe (2005): Co-authored with Jacques Derrida and others, this collection of essays reflects on Europe's role in the world, particularly in the context of the Iraq War.

- Der gespaltene Westen. Kleine politische Schriften X (The Divided West: Small Political Writings X) (2006): Examines the political and cultural divisions within the Western world.

- The Dialectics of Secularization (2007): A dialogue with Joseph Ratzinger (Pope Benedict XVI) on the relationship between reason and religion in modern society.

- Between Naturalism and Religion: Philosophical Essays (2008): Explores the tension and potential for dialogue between naturalism and religious belief.

- Europe. The Faltering Project (2009).

- Zur Verfassung Europas. Ein Essay (On the Constitution of Europe: An Essay) (2011).

- The Crisis of the European Union (2012): Analyzes the challenges facing European integration during the Eurozone crisis.

- Nachmetaphysisches Denken II. Aufsätze und Repliken (Postmetaphysical Thinking II: Essays and Replies) (2012).

- Im Sog der Technokratie. Kleine politische Schriften XII (In the Wake of Technocracy: Small Political Writings XII) (2013).

- Auch eine Geschichte der Philosophie (This Too a History of Philosophy) (2019): A two-volume work exploring the constellation of faith and knowledge in Western philosophy.

- A New Structural Transformation of the Public Sphere and Deliberative Politics (2023).

6. Assessment and Impact

Jürgen Habermas's work has had a profound and multifaceted impact across philosophy, sociology, political theory, and other fields, making him one of the most influential thinkers of the late 20th and early 21st centuries.

6.1. Academic Impact and Evaluation

Habermas's theories, particularly those of communicative rationality and the public sphere, have profoundly influenced academia. His development of communicative rationality, which posits that rationality resides in the structures of interpersonal linguistic communication rather than in cosmic structures or subjective consciousness, offers a powerful framework for understanding social interaction and human emancipation. This theory has been widely adopted and debated in fields ranging from communication studies and political science to ethics and legal theory.

His seminal work, The Structural Transformation of the Public Sphere, laid the foundation for extensive research into the historical development and contemporary challenges of public discourse and democratic participation. It has significantly influenced media studies, urban planning, and critical theory, leading to a deeper understanding of how public opinion is formed and influenced in modern societies.

Habermas's defense of modernity and civil society has served as a major philosophical alternative to various forms of poststructuralism. While acknowledging the pathologies of modern society, he consistently champions the potential for human reason to achieve a more humane, just, and egalitarian world. His influential analysis of late capitalism and its legitimation crises continues to be a cornerstone of critical social theory, offering insights into the dynamics of power and social change in advanced industrial societies.

He perceives the rationalization, humanization, and democratization of society as the institutionalization of the inherent potential for rationality within the communicative competence unique to the human species. Habermas contends that while this competence has evolved, it is often suppressed or weakened in contemporary society due to the dominance of strategic/instrumental rationality in major social domains like the market and the state, where the logic of the system often supplants that of the lifeworld. Bibliometric studies demonstrate his continuing influence and increasing relevance in the humanities and social sciences, with him consistently ranking among the most cited authors.

6.2. Criticisms and Controversies

Despite his widespread influence, Habermas has also been a subject of significant criticisms and controversies throughout his career. One of the most notable incidents involved his controversial "left fascism" remark. During the turbulent student movements of the late 1960s, he critically condemned what he perceived as the students' violent and anarchic actions, labeling them as a "false revolution" and "counterproductive," and controversially characterizing some aspects as "left fascism." This pronouncement alienated many on the left and drew him into direct conflict with the student movement, leading to his temporary departure from the University of Frankfurt. His critics argued that this statement reflected a conservative turn or a misunderstanding of radical protest, while his supporters saw it as a principled critique of totalitarian tendencies regardless of political alignment.

His reinterpretation of Marxism and his assertion that the welfare state, through Keynesian economics, "pacified class conflict" after 1945 also drew criticism, notably from Italian philosopher Domenico Losurdo. Losurdo argued that Habermas's claim overlooked the role of class struggle in the emergence of the welfare state and uncritically assumed its permanence, ignoring its later precariousness and dismantling.

Furthermore, Habermas's engagement with postmodernism led to mutual critiques. Postmodernist thinkers often criticized his adherence to Enlightenment reason and universalist claims, viewing them as totalizing or exclusionary. Habermas, in turn, criticized postmodernists for their perceived ambiguity between theory and literature, their concealed normative sentiments, their totalizing perspective that failed to differentiate social phenomena, and their neglect of everyday life practices, which he considered central. These debates highlighted fundamental divergences on the nature of rationality, truth, and social critique in contemporary philosophy.

6.3. Influence in South Korea

Habermas's philosophy has had a notable reception and impact within South Korean academia and intellectual circles, particularly since the late 1980s. Initially, his works faced obstacles; until 1986, his books were not readily available in South Korea, and attempts to translate them in that year were unsuccessful. However, from 1994 onwards, his works began to be actively translated and published, gaining significant attention.

His ideas, especially on the public sphere and communicative rationality, resonated deeply in a society undergoing rapid democratization and grappling with issues of freedom of expression and state authority. Habermas's concept of the "public space" (공론장Korean, gongnonjang) as a democratic arena where citizens can freely articulate their opinions, interests, and needs, became particularly relevant in the context of South Korea's evolving civil society and its struggles against authoritarianism.

Habermas also gained prominence for his direct engagement with South Korean political and human rights issues. He expressed concern for the treatment of critical figures in South Korea, such as the poet Kim Ji-ha and the philosopher Song Du-yul. Notably, Song Du-yul was his doctoral student. In 2003, when Song Du-yul faced charges under the National Security Act upon his return to Korea, Habermas publicly criticized the South Korean government's perceived violence and its disregard for freedom of expression and thought. In one instance, reportedly based on a misunderstanding of a situation involving Song Du-yul receiving an award while under detention, Habermas advised Song to seek refuge at the German embassy in Seoul. This highlights Habermas's commitment to advocating for human rights and intellectual freedom beyond his immediate academic environment. His public interventions underscored the relevance of his universalist principles in specific political contexts.