1. Overview

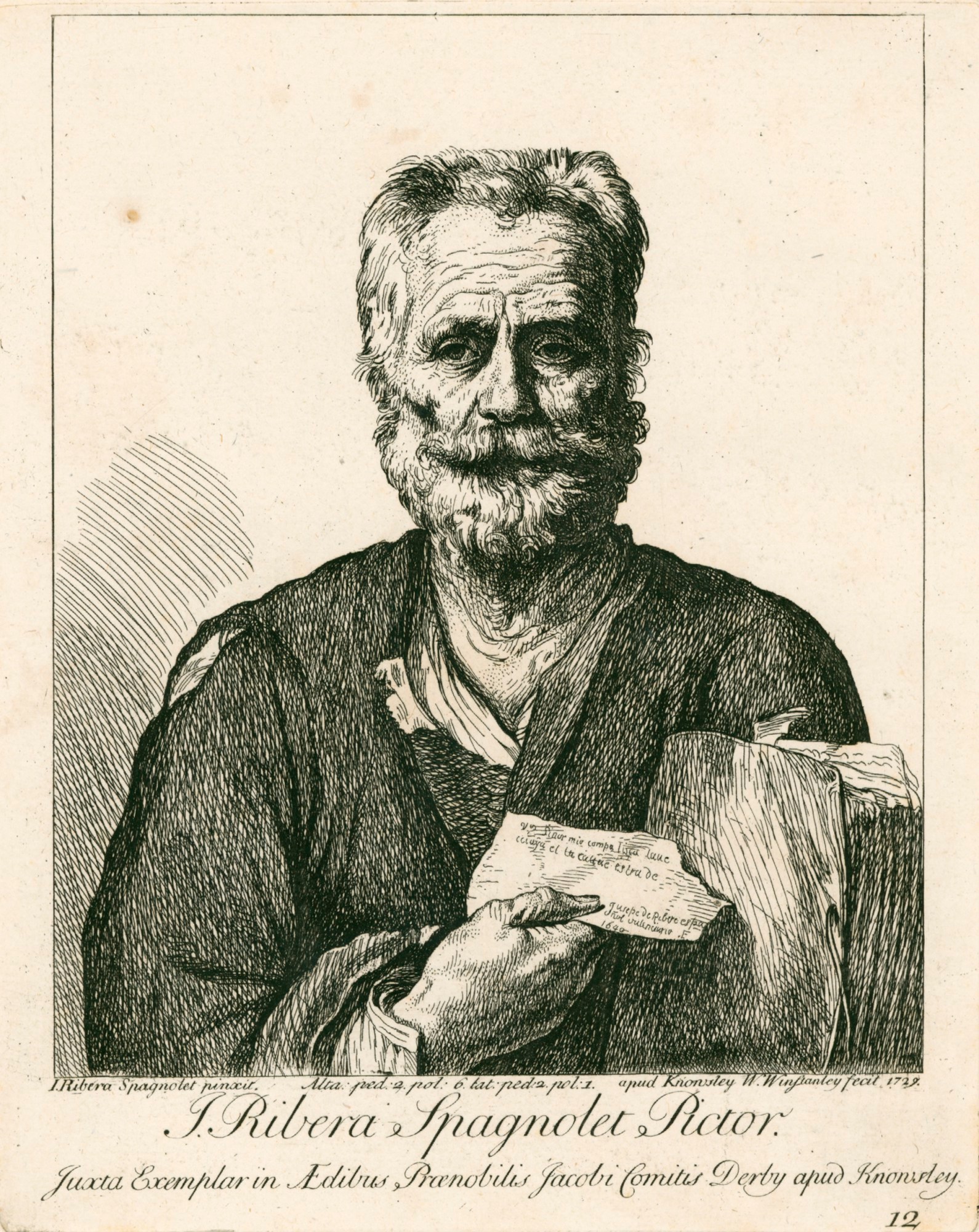

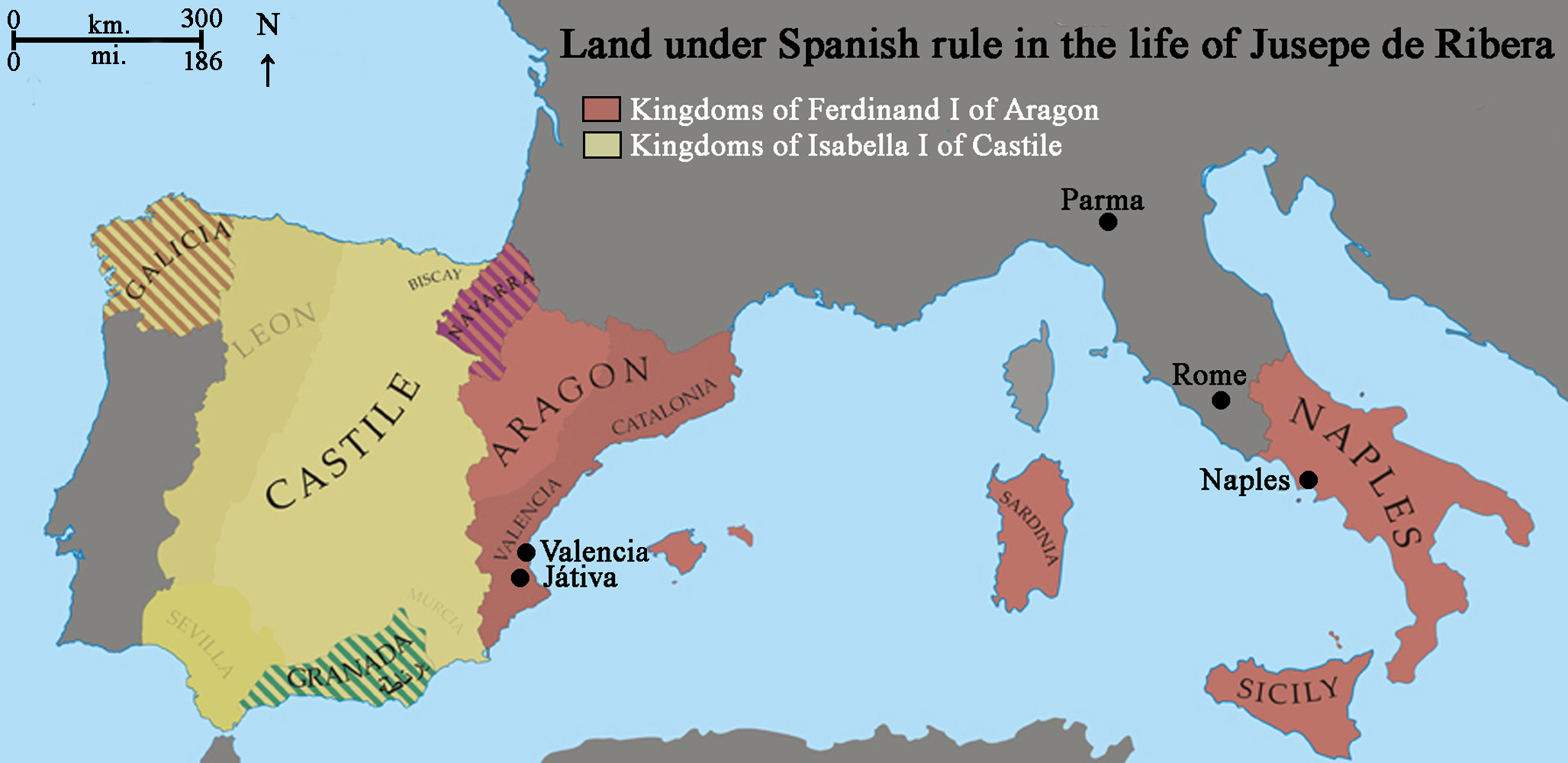

Jusepe de Ribera (baptized February 17, 1591 - November 3, 1652) was a Spanish painter and printmaker of the Baroque period. Although he was born in Spain, he spent the majority of his artistic career in Italy, primarily in Naples, which was then under Spanish rule. His contemporaries and early historians often referred to him as Lo Spagnolettothe Little SpaniardItalian. Ribera is considered one of the major artists of Spanish Baroque painting, alongside Francisco de Zurbarán, Bartolomé Esteban Murillo, and Diego Velázquez. He is recognized as a leading figure of the Neapolitan School and a significant European master of the 17th century.

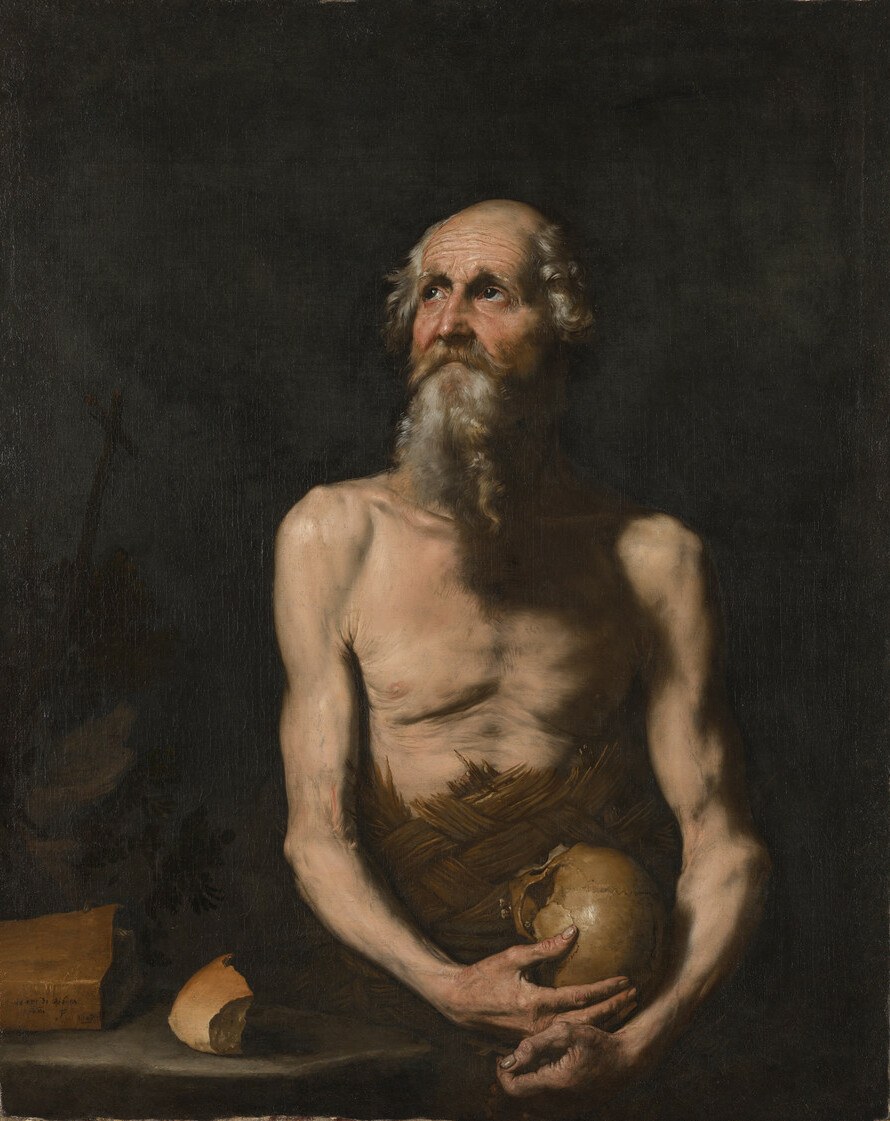

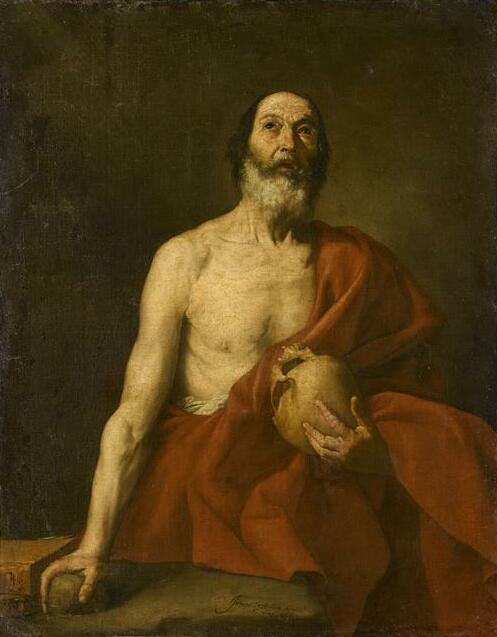

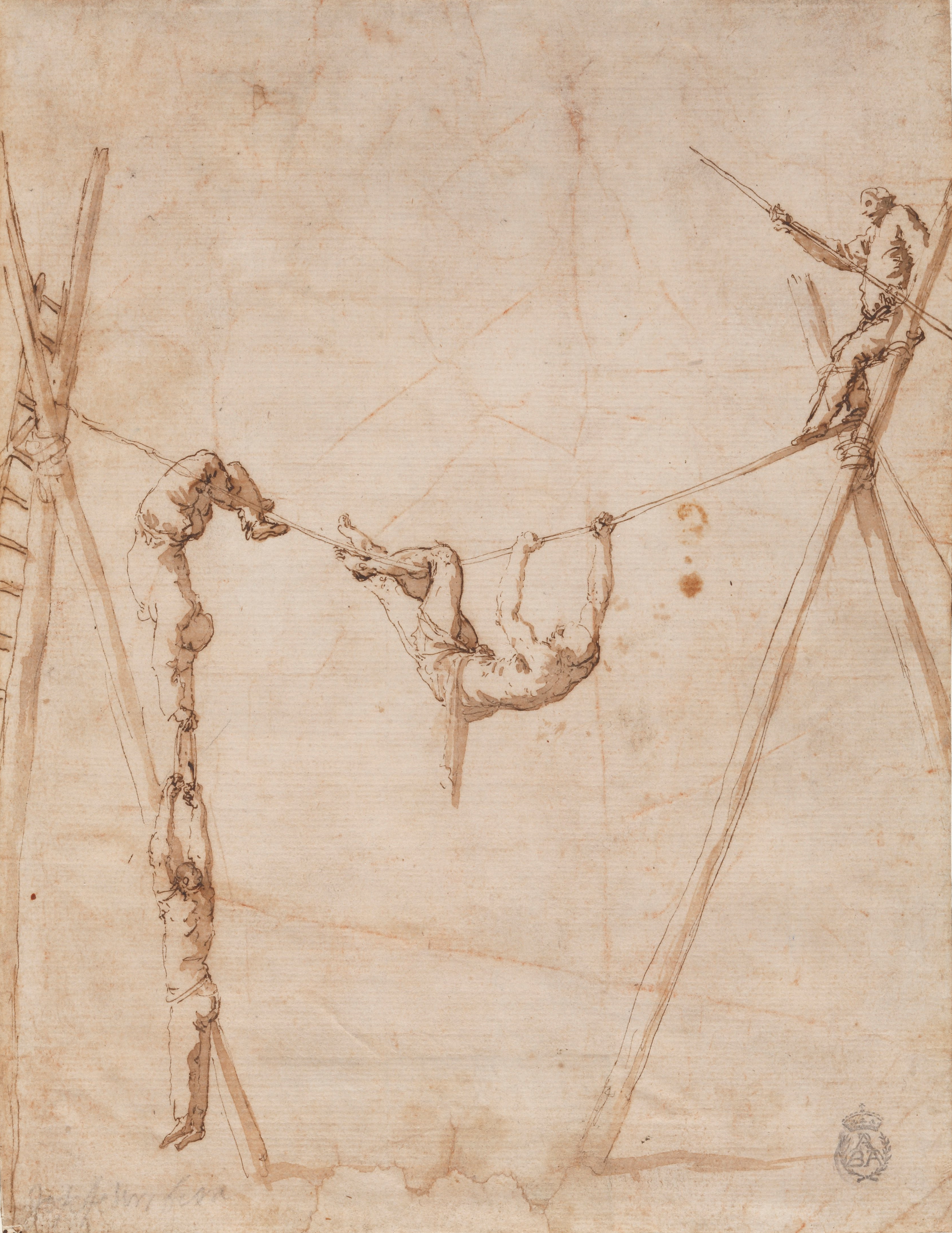

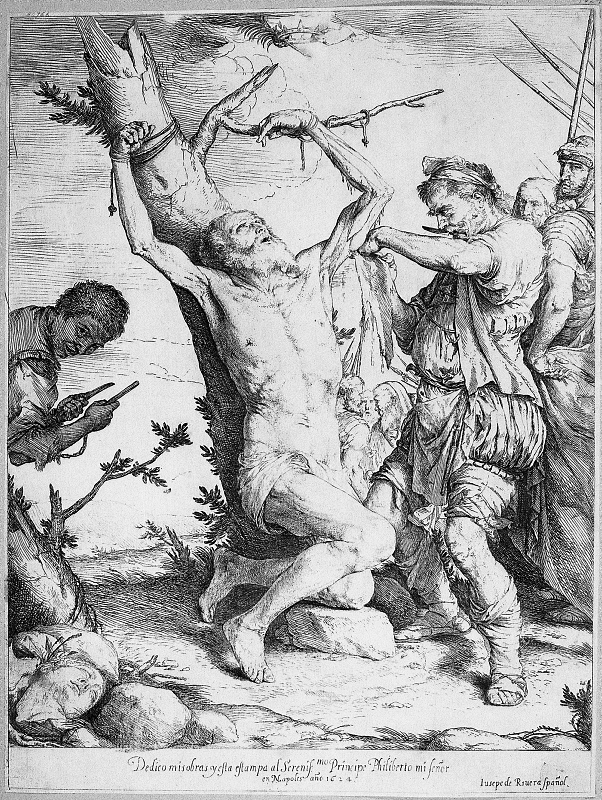

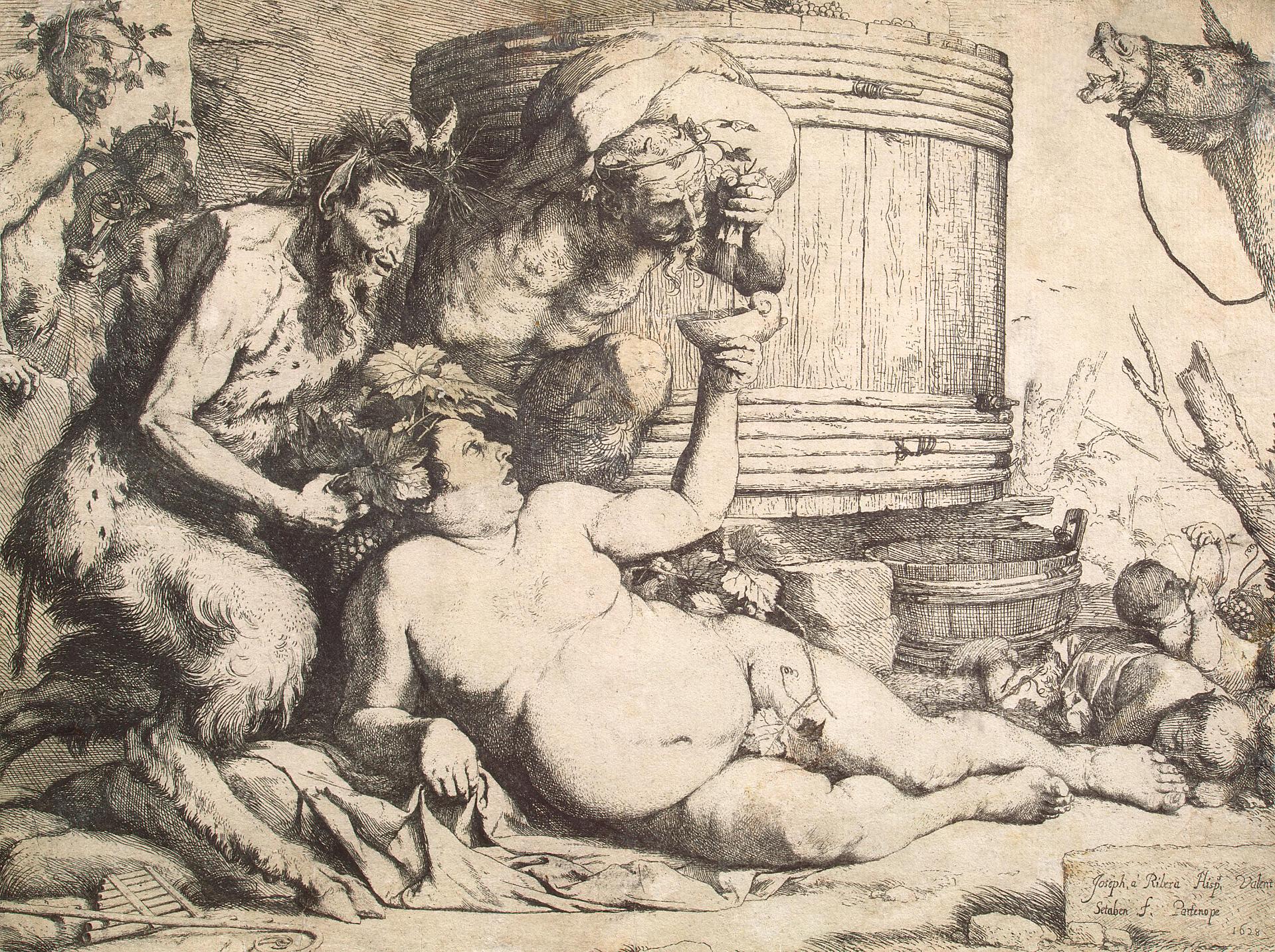

His artistic style is fundamentally characterized by his mastery of Tenebrism, a technique that employs dramatic chiaroscuro (strong contrasts between light and dark) and unflinching realism. He is particularly known for his often brutal depictions of martyrdoms, showing bound saints and satyrs in agony, as well as for portraying ordinary people-such as workers, beggars, and the elderly-as models for religious and philosophical figures. While his early works emphasized this stark realism, his later style evolved to incorporate softer light, richer colors, and more complex compositions, though he never fully abandoned his Caravaggisti influences. Ribera's extensive oeuvre includes history paintings, mythological scenes, portraits, still lifes, and landscapes.

2. Early Life and Background

Jusepe de Ribera's early life and artistic beginnings are marked by some historical uncertainties, particularly regarding his initial training before his move to Italy.

2.1. Birth and Childhood

Jusepe de Ribera was baptized on February 17, 1591, in Játiva, Spain, a town located about 37 mile (60 km) south of Valencia. His parents were Simón and Margarita (née Cucó) Ribera, who had married in 1588. His father's occupation was a shoemaker, and some sources suggest he may have had a substantial business. Ribera was one of three sons, with an older brother, Jerónimo (born 1588), and a younger brother, Juan (born 1593), who also became a painter. Early accounts suggest his parents hoped he would pursue a scholarly path, but he showed little interest in academic studies. There is a significant gap in historical records regarding the first 20 years of his life following his baptism.

2.2. Early Artistic Training and Aspirations

The details of Ribera's early artistic training and education remain largely unknown and are subjects of ongoing historical interest. While the 18th-century biographer Antonio Palomino stated that Ribera apprenticed with the Valencian painter Francesc Ribalta, there is no concrete evidence to confirm this connection, and many modern historians have begun to question this theory. Furthermore, Ribera's drawing technique is thought by some to suggest a distinctly Italian artistic education.

Ribera harbored a strong desire to study art in Italy. Evidence suggests he may have arrived on the Italian peninsula as early as 1605 or 1606, when he was just 14 or 15 years old, or possibly by 1608 or 1609. The frequent remarriages of his father-in 1597 when Jusepe was six, and again in 1607 when he was sixteen-might indicate a period of disruption or lack of stability in his youth, potentially contributing to his early departure from Spain. Notably, Ribalta's mature, Caravaggesque style, which Ribera supposedly learned from, only fully developed around 1614, by which time Ribera was already documented as working in Italy.

3. Artistic Career in Italy

Ribera's career in Italy saw him establish his reputation in Rome before becoming the leading painter in Naples under Spanish patronage.

3.1. Early Italian Period (Parma and Rome)

Ribera's presence in Italy is first confirmed in June 1611, when he was in Parma. At the young age of 20, he received a commission for a public altarpiece, a painting of Saint Martin Sharing His Cloak with a Beggar for the Church of San Prospero. This commission, given to a foreigner, indicates his burgeoning reputation. While in Parma, he was under the protection of the ducal House of Farnese, which reportedly caused some resentment among local artists. The painting itself is now lost but is known through copies and prints.

By October 1613, Ribera is documented in Rome, where he became a member of the prestigious Accademia di San Luca. Parish records from 1615 and 1616 confirm his residence on the Via Margutta, an area known as the "foreigners' quarter," where he lived a seemingly bohemian life with his brothers, Jerónimo and Juan, the latter also a painter. Rome at this time was the vibrant "fountainhead of the Baroque," attracting artists from across Europe, including figures like Gerrit van Honthorst, Simon Vouet, and Adam Elsheimer, all of whom were exploring the techniques of chiaroscuro and Tenebrism in the wake of Caravaggio.

According to Giulio Mancini's Considerazioni sulla pittura (1614-1621), Ribera quickly gained a strong reputation in Rome, with even established painters like Guido Reni expressing admiration for his work. Mancini described Ribera as a follower of Caravaggio, but one who was more experimental and bolder. Despite earning significant profits, Ribera was also noted for his occasional laziness and extravagant spending. He reportedly had issues with Roman authorities for neglecting his Easter confession and eventually left Rome in July 1616 to avoid his creditors.

3.2. Neapolitan Period (1616-1652)

In late 1616, Jusepe de Ribera made a permanent move to Naples, then part of the Spanish Empire and governed by a succession of Spanish viceroys. This move was reportedly to escape his creditors in Rome, as he had a tendency to live beyond his means despite his high income. In November 1616, he married Caterina Azzolino, the daughter of Giovanni Bernardino Azzolino, a Sicilian-born Neapolitan painter. His father-in-law's connections proved instrumental in establishing Ribera as a significant figure in the Neapolitan art scene, where his presence would have a lasting impact.

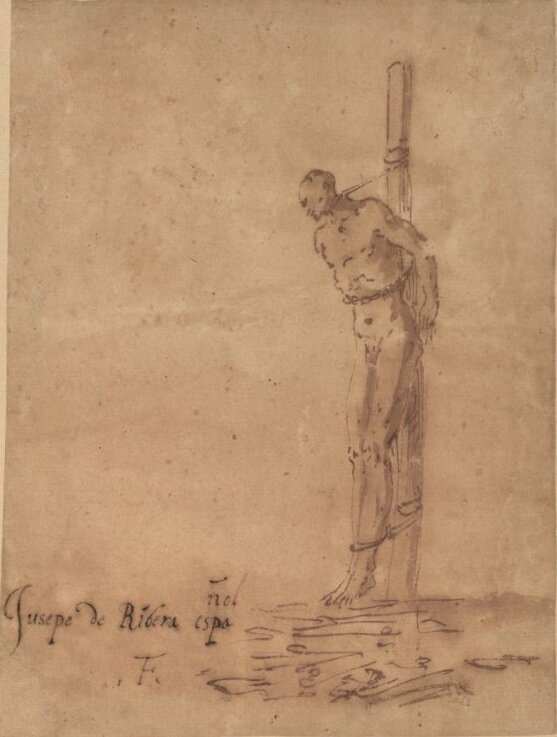

Ribera's Spanish nationality provided him with a crucial advantage, aligning him with the city's small Spanish governing class, as well as with influential collectors and art dealers from the Spanish Netherlands. It was at this point that he began signing his works as "Jusepe de Ribera, español" (Jusepe de Ribera, Spaniard). He quickly garnered the attention of the Viceroy, Pedro Téllez-Girón, 3rd Duke of Osuna, who commissioned several major works from him, some of which showed the influence of Guido Reni.

While few paintings survive from the period between 1620 and 1626, this was a highly productive time for his printmaking, with many of his finest prints being created, partly to attract attention beyond Naples. His career flourished in the late 1620s, solidifying his position as the leading painter in Naples. In 1626, he received the prestigious Order of Christ Cross from Pope Urban VIII. Although Ribera never returned to Spain, many of his paintings were brought there by returning Spanish officials, and his etchings were distributed by art dealers, significantly influencing Spanish painters of the period, including Diego Velázquez and Bartolomé Esteban Murillo.

Ribera has been controversially described in early biographies as being self-interested and condescending, and he was reputedly the leader of the so-called "Cabal of Naples". This alleged group, which supposedly included the Greek painter Belisario Corenzio and the Neapolitan Battistello Caracciolo, aimed to monopolize art commissions in Naples. They were said to employ various tactics, including intrigue, sabotage of rival artists' works, and even threats of violence, to deter external competitors such as Annibale Carracci, the Cavalier d'Arpino, Guido Reni, and Domenichino. This "cabal" is said to have disbanded following Domenichino's death in 1641. However, these accounts from early biographers lack documentary evidence and are often considered erroneous or exaggerated.

4. Artistic Style and Themes

Ribera's artistic output is characterized by a distinctive style that evolved over his career, encompassing a wide range of themes from religious narratives to portraits of common people.

4.1. Tenebrism and Realism

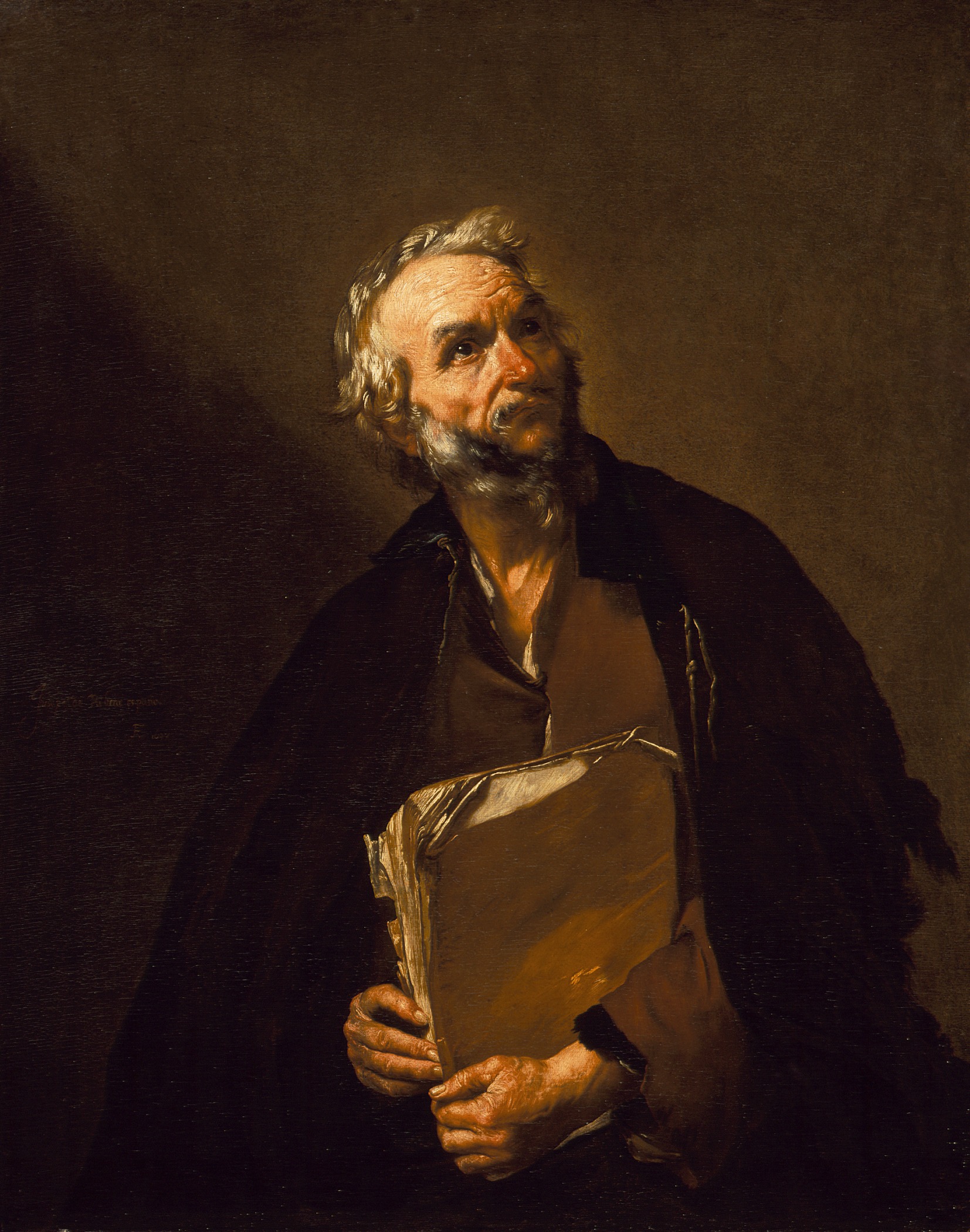

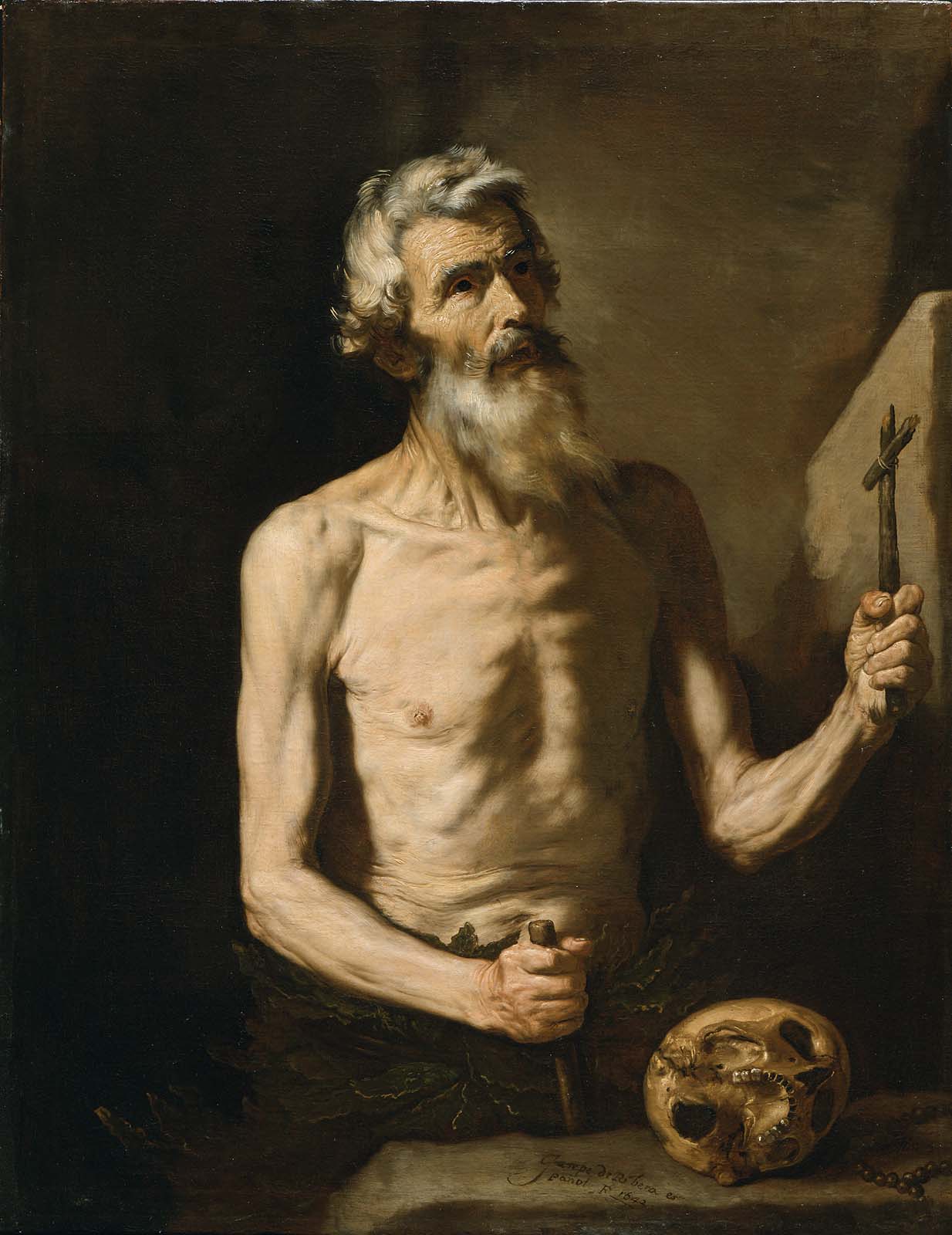

Ribera's artistic style is fundamentally defined by his mastery of Tenebrism, a technique that employs dramatic chiaroscuro-strong contrasts between light and dark-to create a heightened sense of drama and volume. This intense lighting is coupled with an unflinching realism, particularly evident in his portrayal of human suffering and the physical decay of the body. He was renowned for his often gruesome depictions of martyrdoms, which vividly portray human cruelty and violence with startling naturalism, such as saints or mythological figures shown in agony, being flayed or crucified.

A significant portion of Ribera's oeuvre consists of half-length portraits of ordinary people, including fishermen, dockworkers, beggars, and the elderly, often depicted with wrinkled skin and ragged clothing. These figures served as models for his portrayals of various philosophers, saints, apostles, and allegorical figures, rendered with a raw visual intensity that captures their humanity. His commitment to realism meant that he did not idealize his subjects, instead depicting their physical forms, even in their decline, with a profound honesty that reflected the influence of Caravaggio.

4.2. Evolution of Style

Ribera's style underwent a notable evolution throughout his career. His early works were characterized by a stark, almost brutal realism achieved through intense Tenebrism. However, by the early 1630s, his approach began to shift. While maintaining his fundamental Caravaggisti influences, his paintings started to feature more diffused lighting, a richer palette of colors, and increasingly complex compositions. This transition is evident in works such as The Clubfoot (1642), where the lighting is softer compared to his earlier, more dramatic pieces. This later period also saw an expansion of his thematic repertoire and an absorption of elements from classicism, particularly from the Bolognese School. This led to a style marked by more stable compositions, clearer colors, and a sense of quiet lyricism and nobility.

4.3. Major Themes

Ribera's thematic range was diverse, though he is most famously associated with his powerful history paintings, particularly those depicting intense martyrdoms. These scenes often portray figures, whether saints or mythological beings, undergoing brutal suffering, such as being flayed or crucified in agony. Beyond these dramatic religious narratives, he also explored subjects from Greek mythology, often with a similar degree of violence, as seen in his renditions of Apollo and Marsyas and Tityos.

Less common but equally accomplished are his occasional portrait paintings, still lifes, and landscape paintings. Nearly half of his surviving works are half-length portraits of ordinary people-workers, beggars, and the elderly-who pose as various philosophers, saints, apostles, and allegorical figures. These works showcase his commitment to depicting common humanity.

His landscapes, though rare in Spanish painting before the 19th century, were praised in historical literature and are now recognized as significant. Two large canvases from 1639, identified in the collection of the Palacio de Monterrey in Salamanca, are notable surviving examples. Art historians have remarked on the originality of Ribera's approach to landscape, contrasting it with contemporary Roman landscape painting by artists like Nicolas Poussin and Claude Lorrain. Alfonso Emilio Pérez Sánchez, former director of the Museo del Prado, asserted that these landscapes "assure Ribera a principal place in the history of Neapolitan landscape painting" and are uniquely recognizable as his.

5. Major Works

Ribera's extensive body of work includes numerous oil paintings, as well as significant contributions to drawing and printmaking.

5.1. Oil Paintings

Ribera's oil paintings encompass a wide range of subjects, from dramatic history paintings and mythological scenes to profound portrayals of saints, apostles, and allegorical figures.

5.2. Drawings

Ribera was also an accomplished draftsman, producing studies of figures, anatomy, and imaginative scenes.

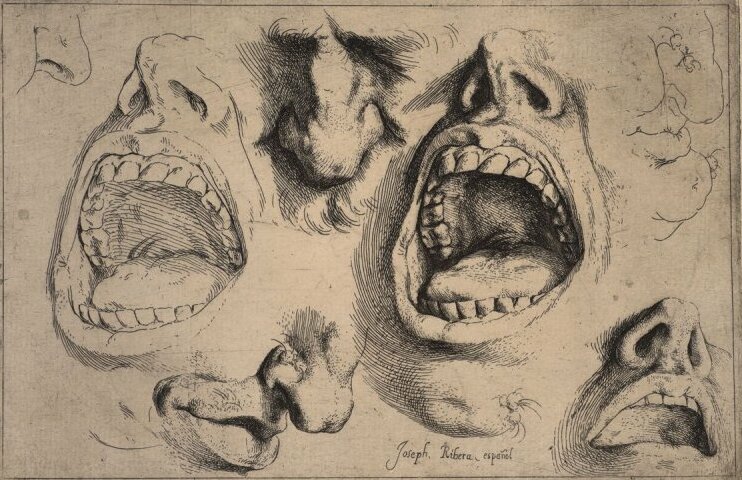

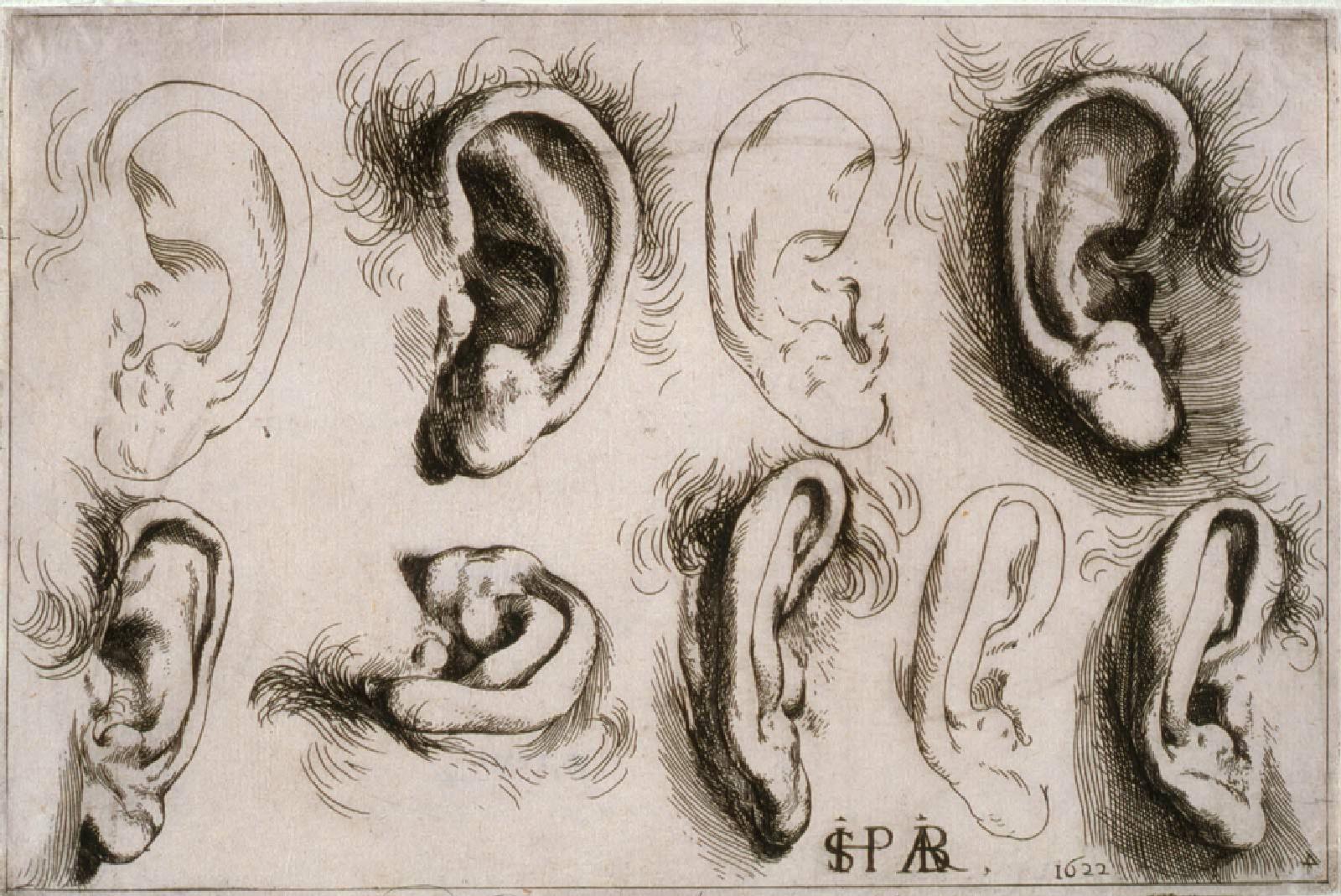

5.3. Prints and Etchings

Ribera was a highly important printmaker, considered the most significant Spanish printmaker before Francisco Goya. He produced approximately forty prints, with the majority created in the 1620s.

6. Private Life

Beyond his prolific artistic career, limited information is available about Ribera's private life. It is known that he married Caterina Azzolino in November 1616. Around 1644, his daughter married a Spanish nobleman within the administration, though he reportedly died soon after their marriage.

7. Later Life and Health Decline

From the mid-1640s onward, Ribera's health began to decline significantly, which greatly reduced his ability to work. Despite his personal struggles, his workshop continued to produce works under his direction. During the uprising against Spanish rule in 1647-1648, Ribera and his family sought refuge in the palace of the Viceroy. By 1651, he was experiencing severe financial difficulties, leading him to sell his home. He continued to produce several acclaimed paintings when his health permitted, even into the last year of his life. Jusepe de Ribera died on November 3, 1652.

8. Legacy and Influence

Ribera's impact on the art world extended far beyond his lifetime, influencing numerous artists and shaping the trajectory of Baroque painting in both Italy and Spain.

8.1. Influence on Later Artists

Ribera's work remained influential after his death, largely due to the adoption of his distinctive hyper-naturalistic depictions of violence by his pupils and followers. Among his most distinguished followers were Salvator Rosa and Luca Giordano, both of whom may have been his direct pupils. Other artists who studied with him or were significantly influenced by his style include Giovanni Do, the Flemish painter Hendrick de Somer (known in Italy as 'Enrico Fiammingo'), Michelangelo Fracanzani, and Aniello Falcone, who is recognized as the first significant painter of battle-pieces. His artistic innovations also left a lasting mark on other Spanish painters of the period, including prominent figures like Diego Velázquez and Bartolomé Esteban Murillo.

8.2. Critical Reception and Exhibitions

Historically, Ribera's art has undergone various assessments. While his work remained in fashion for some time after his death, a gradual rehabilitation of his international reputation began in the late 20th century. This was significantly aided by a series of major exhibitions, including one of his prints and drawings in Princeton in 1973, followed by comprehensive exhibitions of his works in all media at the Royal Academy in London in 1982 and at the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York in 1992. These exhibitions brought his oeuvre to wider critical and scholarly attention. In 2006, a comprehensive catalogue raisonné of Ribera's work was published by Nicola Spinosa, the former director of the Museo di Capodimonte in Naples, further solidifying his place in art history.

9. Biographical Controversies

Early biographies of Jusepe de Ribera contain a substantial amount of information that has since been proven erroneous by modern research. Biographers from the 17th and 18th centuries, such as Bernardo de' Dominici, Carlo Celano, and Antonio Palomino, contributed to a narrative that was pervasive well into the 20th century and is occasionally still repeated today.

For instance, it was long believed that Ribera was born in 1587, with varying accounts placing his birthplace in Gallipoli, Apulia or Lecce. Some biographies claimed he descended from nobility, while others identified his father as a Spanish army officer. However, research and newly discovered documents in the 20th century have definitively disproven these claims, establishing his birth year as 1591 in Játiva and his father's occupation as a shoemaker.

Other episodes and events in Ribera's life also remain unverified. Early accounts, still sometimes repeated, state that Ribera began his art education in Valencia as a pupil of Francesc Ribalta. While plausible, there is no concrete evidence to confirm this connection.

De Dominici's biography, in particular, described Ribera as an egotistical and condescending individual with reprehensible behavior. He was reputed to have been the chief of the so-called "Cabal of Naples", with his alleged abettors being the Greek painter Belisario Corenzio and the Neapolitan Battistello Caracciolo. This group was said to have monopolized Neapolitan art commissions through intrigue, sabotage, and threats against rival artists. However, there are no real documents or records to substantiate or discredit these claims beyond these early biographies. De Dominici's account has been dismissed as "barefaced lies" by one modern historian and "a caricature" by another, although the latter noted that a critical examination of it can still provide some insights into the artistic climate of the time.