1. Overview

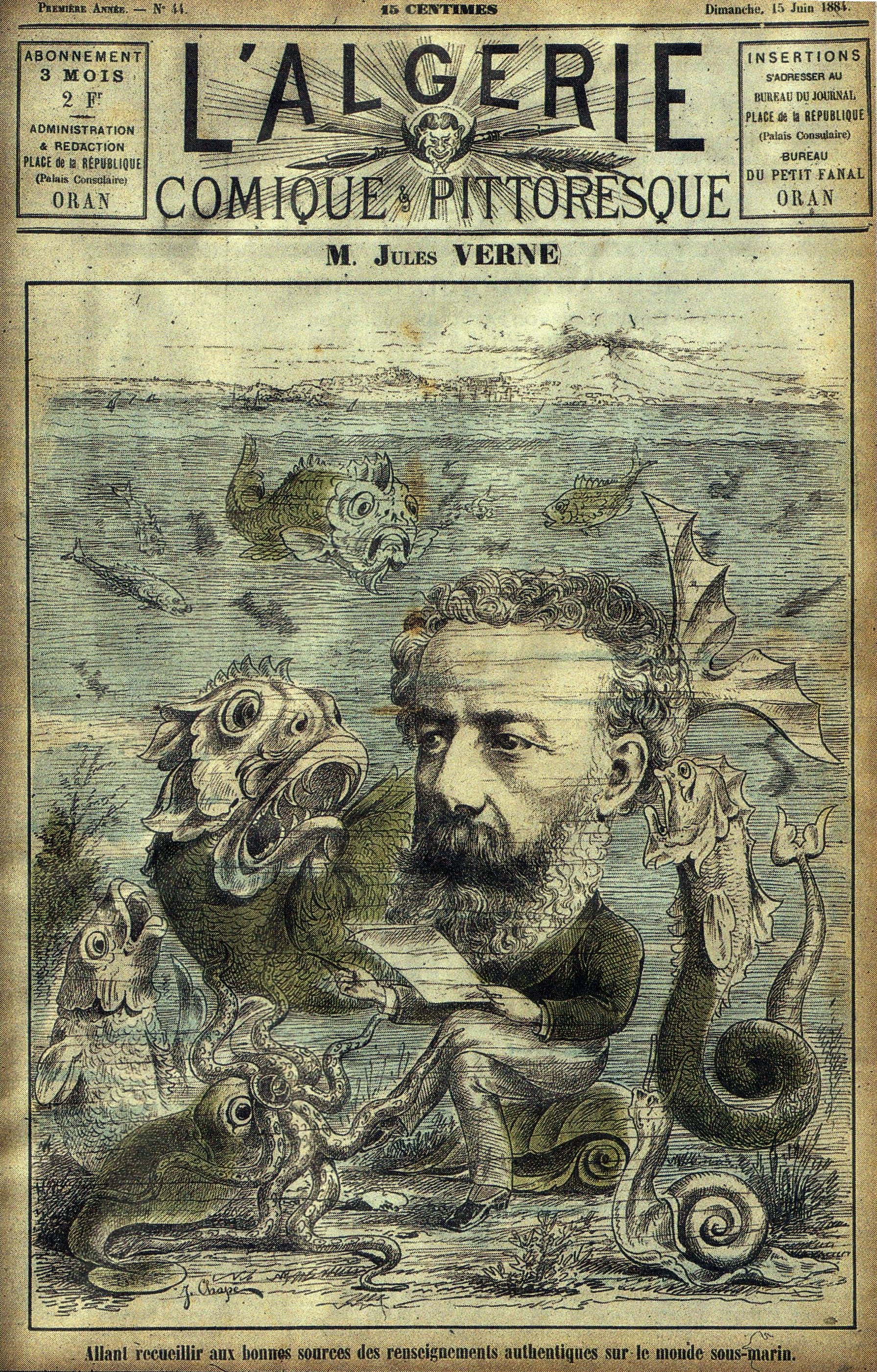

Jules Gabriel Verne, born on February 8, 1828, and passing away on March 24, 1905, was a pioneering French novelist, poet, and playwright. He is widely recognized as one of the "fathers of science fiction" alongside H. G. Wells and Hugo Gernsback, having profoundly influenced the genre's development. His collaboration with publisher Pierre-Jules Hetzel led to the creation of the acclaimed Voyages extraordinaires series, a collection of adventure novels that blended rigorous scientific research with captivating narratives. This series includes some of his most famous works, such as Journey to the Center of the Earth (1864), Twenty Thousand Leagues Under the Seas (1870), and Around the World in Eighty Days (1872).

Verne's novels, always meticulously researched according to the scientific knowledge available at the time, are generally set in the latter half of the 19th century, incorporating the technological advancements of the era. Beyond his novels, he also produced numerous plays, short stories, autobiographical accounts, poetry, songs, and various scientific, artistic, and literary studies. His extensive body of work has been adapted across diverse media, including film, television, comic books, theater, opera, music, and video games, since the early days of cinema.

In France and across most of Europe, Verne is considered a significant author, having exerted a wide influence on literary movements like the avant-garde and surrealism. However, his reputation differed notably in the Anglosphere, where he was often categorized as a writer of genre fiction or children's books, largely due to heavily abridged and altered English translations of his novels. Since the 1980s, his literary standing has seen a marked improvement globally. Since 1979, Jules Verne has been the second most-translated author in the world, ranking below Agatha Christie and above William Shakespeare. In the 2010s, he was recognized as the most translated French author worldwide. In France, 2005 was designated "Jules Verne Year" to commemorate the centenary of his death.

2. Life

Jules Verne's life was marked by a blend of strict familial expectations, early literary aspirations, and a lifelong dedication to scientific and geographical exploration through his writing.

2.1. Early Life and Education

Jules Gabriel Verne was born on February 8, 1828, on Île Feydeau, a small artificial island on the Loire River within the city of Nantes, France. His birthplace was the house of his maternal grandmother, Dame Sophie Marie Adélaïde Julienne Allotte de La Fuÿe. His parents were Pierre Verne, an avoué (attorney) originally from Provins, and Sophie Allotte de La Fuÿe, a Nantes woman from a local family of navigators and shipowners with distant Scottish descent. In 1829, the Verne family moved nearby, where his brother Paul was born the same year. Three sisters followed: Anne "Anna" (1836), Mathilde (1839), and Marie (1842).

In 1834, at the age of six, Verne began attending a boarding school in Nantes. His teacher, Madame Sambin, was the widow of a naval captain who had disappeared decades earlier. Madame Sambin frequently told her students that her husband was a shipwrecked castaway who would eventually return, much like Robinson Crusoe from his desert island. This theme of the robinsonade (a story about castaways) would later appear in many of Verne's novels, including The Mysterious Island (1874), Second Fatherland (1900), and The School for Robinsons (1882).

In 1836, Verne enrolled in École Saint-Stanislas, a Catholic school chosen by his pious father. He quickly excelled in recitation from memory (mémoire), geography, Greek, Latin, and singing. That same year, his father purchased a vacation home in Chantenay (now part of Nantes) on the Loire. In his brief memoir Souvenirs d'enfance et de jeunesse (Memories of Childhood and Youth, 1890), Verne recalled a deep fascination with the river and the numerous merchant vessels navigating it. He also spent vacations at Brains, at the home of his uncle Prudent Allotte, a retired shipowner who had traveled the world and served as mayor of Brains. Verne enjoyed playing endless rounds of the Game of the Goose with his uncle, and both the game and his uncle's name were later immortalized in his novels The Will of an Eccentric (1900) and Robur the Conqueror (1886).

A popular legend recounts that in 1839, at age 11, Verne secretly boarded the three-mast ship Coralie as a cabin boy, intending to travel to the Indies to retrieve a coral necklace for his cousin Caroline. The ship reportedly stopped at Paimboeuf on its departure night, where Pierre Verne caught his son and made him promise to travel "only in his imagination." While this story, largely propagated by Verne's niece Marguerite Allotte de la Füye, is now considered an exaggeration, it may have been inspired by a real incident.

In 1840, the Vernes moved to a large apartment in Nantes, where Marie, the youngest child, was born in 1842. That same year, Verne transferred to another religious school, the Petit Séminaire de Saint-Donatien, as a lay student. His unfinished novel Un prêtre en 1839 (A Priest in 1839), written in his teens and one of his earliest surviving prose works, describes the seminary in disparaging terms, possibly reflecting his experiences there. From 1844 to 1846, Verne and his brother attended the Lycée Royal (now the Lycée Georges-Clemenceau) in Nantes. After completing courses in rhetoric and philosophy, he passed his baccalauréat in Rennes on July 29, 1846, with a "Good Enough" grade.

By 1847, at 19, Verne had seriously begun writing longer works in the style of Victor Hugo, including Un prêtre en 1839 and two completed verse tragedies, Alexandre VI and La Conspiration des poudres (The Gunpowder Plot). However, his father expected Jules, as the eldest son, to inherit the family law practice rather than pursue a career in literature.

In 1847, Verne's father sent him to Paris to begin law school, and, according to family lore, to distance him from Nantes. His cousin Caroline, with whom he was in love, married Émile Dezaunay, a 40-year-old man, on April 27, 1847. After passing his first-year law exams in Paris, Verne returned to Nantes to prepare for his second year with his father's help. While in Nantes, he met Rose Herminie Arnaud Grossetière, a young woman one year his senior, and fell deeply in love, dedicating about thirty poems to her, including La Fille de l'air (The Daughter of Air), which described her as "blonde and enchanting / winged and transparent." Though his affection seemed reciprocated for a time, Grossetière's parents opposed the match due to Verne's uncertain future, arranging her marriage to Armand Terrien de la Haye, a wealthy landowner ten years her senior, on July 19, 1848. This abrupt marriage caused Verne deep frustration, which he expressed in a hallucinatory letter to his mother. This unfulfilled love affair profoundly influenced his work, leading to a recurring theme of young women married against their will in his novels (e.g., Gérande in Master Zacharius (1854), Sava in Mathias Sandorf (1885), Ellen in A Floating City (1871)), a pattern scholars attribute to an "Herminie complex." The incident also fueled Verne's resentment towards his hometown and Nantes society, which he criticized in his poem La sixième ville de France (The Sixth City of France).

2.2. Literary Beginnings

In July 1848, Verne returned to Paris to complete his law studies, as his father intended. He rented a furnished apartment at 24 Rue de l'Ancienne-Comédie, sharing it with Édouard Bonamy, another student from Nantes. Verne arrived in Paris amidst the French Revolution of 1848, a period of significant political upheaval marked by the overthrow of Louis Philippe I and the establishment of the French Second Republic. Despite the ongoing political demonstrations and social tension, including the June Days uprising, Verne assured his family in letters that the Bastille Day anniversary had passed peacefully.

Verne leveraged family connections to enter Parisian society, frequenting literary salons, particularly those of Mme de Barrère, a friend of his mother's. While diligently pursuing his law studies, he indulged his passion for theater, writing numerous plays. He later recalled being "greatly under the influence of Victor Hugo, indeed, very excited by reading and re-reading his works." Another creative influence was his neighbor, the young composer Aristide Hignard, with whom Verne quickly befriended and for whom he wrote several chansons.

During this period, Verne's letters to his parents often discussed expenses and recurring, violent stomach cramps, which modern scholars hypothesize were colitis. He also suffered the first of four attacks of facial paralysis in 1851, caused by middle ear inflammation, though the cause remained unknown to him. In the same year, Verne was required to enlist in the French army, but was spared by the sortition process, much to his relief. He expressed strong anti-war sentiments in a letter to his father, stating his disdain for military life, a stance he maintained throughout his life despite his father's dismay. Despite these challenges, Verne diligently pursued his law studies, graduating with a licence en droit in January 1851.

Through his salon visits, Verne met Alexandre Dumas in 1849. He became close friends with Dumas' son, Alexandre Dumas fils, and showed him the manuscript for his stage comedy, Les Pailles rompues (The Broken Straws). The two revised the play, and Dumas fils, with his father's help, had it produced by the Opéra-National at the Théâtre Historique in Paris, opening on June 12, 1850.

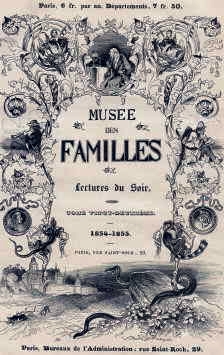

In 1851, Verne met Pierre-Michel-François Chevalier (known as "Pitre-Chevalier"), the editor-in-chief of the magazine Musée des familles (The Family Museum). Pitre-Chevalier sought articles on geography, history, science, and technology, aiming to make educational content accessible through engaging prose or fictional stories. Verne, with his passion for diligent research, particularly in geography, was an ideal candidate. He first offered a short historical adventure story, The First Ships of the Mexican Navy, written in the style of James Fenimore Cooper, who had deeply influenced him. Pitre-Chevalier published it in July 1851, and in August 1851, a second short story, A Voyage in a Balloon. Verne later described the latter, with its blend of adventure, travel, and detailed historical research, as "the first indication of the line of novel that I was destined to follow."

Dumas fils also connected Verne with Jules Seveste, director of the Théâtre Lyrique. Seveste offered Verne an unpaid secretarial position, which Verne accepted, using the opportunity to write and produce several comic operas with Hignard and the librettist Michel Carré. To celebrate his employment, Verne and ten friends formed the Onze-sans-femme (Eleven Bachelors) dining club.

Despite his father's persistent pressure to abandon writing for a legal career, Verne maintained that his success lay only in literature. The ultimatum came in January 1852, when his father offered him his own Nantes law practice. Verne decisively refused, writing, "Am I not right to follow my own instincts? It's because I know who I am that I realize what I can be one day."

During this time, Verne spent considerable time at the Bibliothèque nationale de FranceFrench, researching for his stories and fueling his passion for science and recent discoveries, especially in geography. He befriended the illustrious geographer and explorer Jacques Arago, who traveled extensively despite his blindness. Arago's innovative and witty travel accounts steered Verne towards the developing genre of travel writing.

In 1852, Musée des familles published Verne's novella Martin Paz, set in Lima, and the one-act comedy Les Châteaux en Californie, ou, Pierre qui roule n'amasse pas mousse (The Castles in California, or, A Rolling Stone Gathers No Moss). In April and May 1854, the magazine featured his short story Master Zacharius, an E. T. A. Hoffmann-like fantasy that sharply condemned scientific hubris, followed by A Winter Amid the Ice, a polar adventure story that foreshadowed many of his later novels. The Musée also published unsigned nonfiction popular science articles generally attributed to Verne. His work for the magazine ceased in 1856 due to a serious quarrel with Pitre-Chevalier, a refusal he maintained until Pitre-Chevalier's death in 1863.

While contributing to Pitre-Chevalier's magazine, Verne conceived the idea of a "Roman de la Science" ("novel of science"), a new type of novel that would allow him to integrate the vast factual information he gathered at the Bibliothèque. He reportedly discussed this project with the elder Alexandre Dumas, who had attempted a similar work with his unfinished novel Isaac Laquedem, and who enthusiastically encouraged Verne.

At the end of 1854, a cholera outbreak claimed the life of Jules Seveste, Verne's employer and friend at the Théâtre Lyrique. Although his contract only required one more year of service, Verne remained connected to the theater for several years, seeing additional productions to fruition. He also continued writing plays and musical comedies, most of which remained unperformed.

2.3. Career and Major Activities

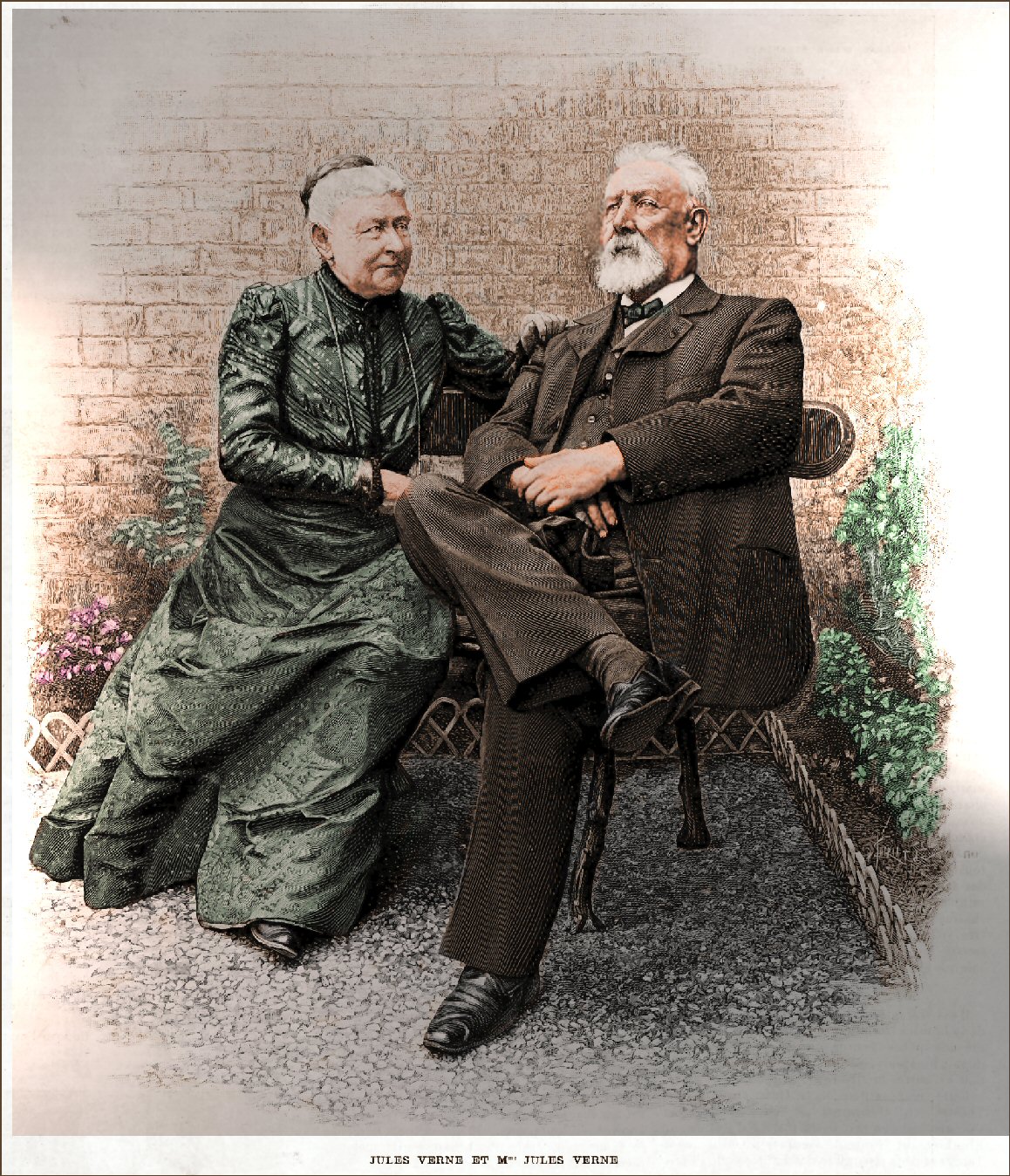

In May 1856, Jules Verne traveled to Amiens to serve as the best man at the wedding of a Nantes friend, Auguste Lelarge. While staying with the bride's family, Verne grew fond of the household and became increasingly attracted to the bride's sister, Honorine Anne Hébée Morel (née du Fraysne de Viane), a 26-year-old widow with two young children. Seeking a stable income and an opportunity to court Morel, he accepted her brother's offer to join a brokerage business. Verne's father was initially hesitant but approved in November 1856. With his financial prospects improving, Verne won Morel's favor, and they married on January 10, 1857.

Verne immersed himself in his new business responsibilities, leaving the Théâtre Lyrique to work full-time as an agent de change (stockbroker) on the Paris Bourse, becoming an associate of Fernand Eggly. He woke early each morning to write before heading to the Bourse, and in his spare time, he continued to frequent the Onze-Sans-Femme club (whose members had all since married). He also continued his scientific and historical research at the Bibliothèque, meticulously copying notes onto notecards-a system he maintained throughout his life. A colleague reportedly observed that Verne "did better in repartee than in business."

In July 1858, Verne and Aristide Hignard embarked on a complimentary sea voyage from Bordeaux to Liverpool and Scotland, offered by Hignard's brother. This, Verne's first trip outside France, deeply impressed him. Upon his return to Paris, he fictionalized his experiences into the semi-autobiographical novel Backwards to Britain (written in late 1859-early 1860, published posthumously in 1989). A second free voyage in 1861 took Hignard and Verne to Stockholm, then to Christiania and through Telemark. Verne hastily returned to Paris, missing the birth of his only biological son, Michel, on August 3, 1861.

Meanwhile, Verne continued developing his "Roman de la Science" concept, which took shape as a travel story across Africa, inspired by his "love for maps and the great explorers of the world." This project eventually became his first published novel, Five Weeks in a Balloon.

In 1862, through their mutual acquaintance Alfred de Bréhat, Verne connected with the publisher Pierre-Jules Hetzel. Verne submitted his manuscript, then titled Voyage en Ballon. Hetzel, already a publisher for renowned authors like Honoré de Balzac, George Sand, and Victor Hugo, had long planned a high-quality family magazine that would combine entertaining fiction with scientific education. He recognized Verne's talent for meticulously researched adventure stories as ideal for his envisioned Magasin d'Éducation et de Récréation (Magazine of Education and Recreation). Hetzel accepted the novel, offering suggestions for improvement. Verne revised it within two weeks, returning the final draft, now titled Five Weeks in a Balloon, which Hetzel published on January 31, 1863.

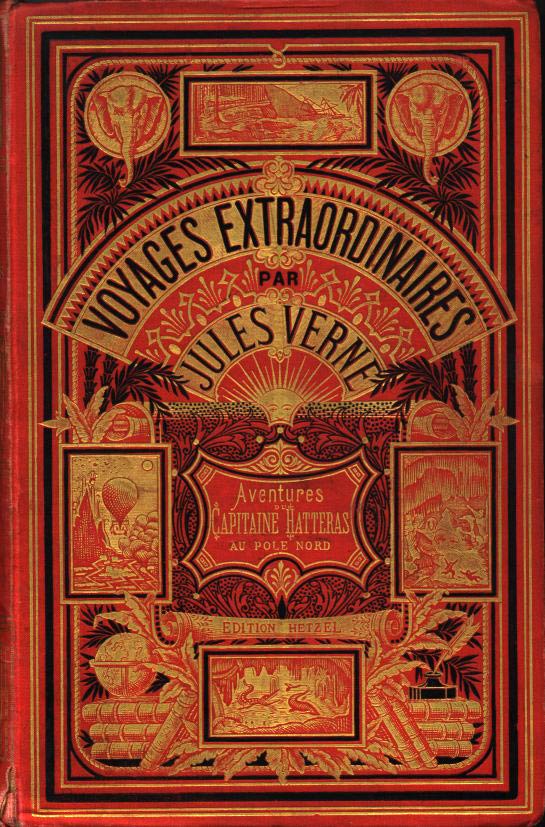

To secure Verne's contributions for the new magazine, Hetzel offered a long-term contract: Verne would provide three volumes of text annually, which Hetzel would purchase outright for a flat fee. Verne, finally finding a steady salary and a guaranteed outlet for his writing, immediately accepted. For the remainder of his life, most of his novels were serialized in Hetzel's Magasin before their book publication, starting with his second novel for Hetzel, The Adventures of Captain Hatteras (1864-65).

When The Adventures of Captain Hatteras was published in book form in 1866, Hetzel publicly announced his literary and educational ambitions for Verne's novels. He stated in a preface that Verne's works would form a novel sequence called the Voyages extraordinaires (Extraordinary Voyages or Extraordinary Journeys). Hetzel declared Verne's aim was "to outline all the geographical, geological, physical, and astronomical knowledge amassed by modern science and to recount, in an entertaining and picturesque format that is his own, the history of the universe." Late in life, Verne confirmed this commission as the running theme of his novels: "My object has been to depict the earth, and not the earth alone, but the universe... And I have tried at the same time to realize a very high ideal of beauty of style. It is said that there can't be any style in a novel of adventure, but it isn't true." However, he also acknowledged the project's immense scope: "Yes! But the Earth is very large, and life is very short! In order to leave a completed work behind, one would need to live to be at least 100 years old!"

Hetzel directly influenced many of Verne's novels, especially in the early years of their collaboration, as Verne was initially eager to please his publisher. For instance, when Hetzel disapproved of the original climax of Captain Hatteras, which included the title character's death, Verne wrote an entirely new conclusion where Hatteras survived. Hetzel also rejected Verne's subsequent submission, Paris in the Twentieth Century, deeming its pessimistic future vision and condemnation of technological progress too subversive for a family magazine. This manuscript, believed lost for some time, was finally published in 1994.

The relationship between publisher and writer shifted around 1869, when a conflict arose over the manuscript for Twenty Thousand Leagues Under the Seas. Verne had initially conceived of the submariner Captain Nemo as a Polish scientist whose vengeful acts targeted the Russians for killing his family during the January Uprising. Hetzel, concerned about alienating the lucrative Russian market for Verne's books, demanded that Nemo be portrayed as an enemy of the slave trade, making him an unambiguous hero. After vehemently resisting, Verne finally compromised by leaving Nemo's past mysterious. Following this disagreement, Verne became notably cooler in his dealings with Hetzel, considering suggestions but often rejecting them outright.

From that point, Verne published two or more volumes a year. Among his most successful works are: Voyage au centre de la TerreFrench (Journey to the Center of the Earth, 1864); De la Terre à la LuneFrench (From the Earth to the Moon, 1865); Vingt mille lieues sous les mersFrench (Twenty Thousand Leagues Under the Seas, 1869); and Le tour du monde en quatre-vingts joursFrench (Around the World in Eighty Days), which first appeared in Le Temps in 1872. Verne was able to live off his writings, but a significant portion of his wealth came from the stage adaptations of Le tour du monde en quatre-vingts jours (1874) and Michel Strogoff (1876), which he co-wrote with Adolphe d'Ennery.

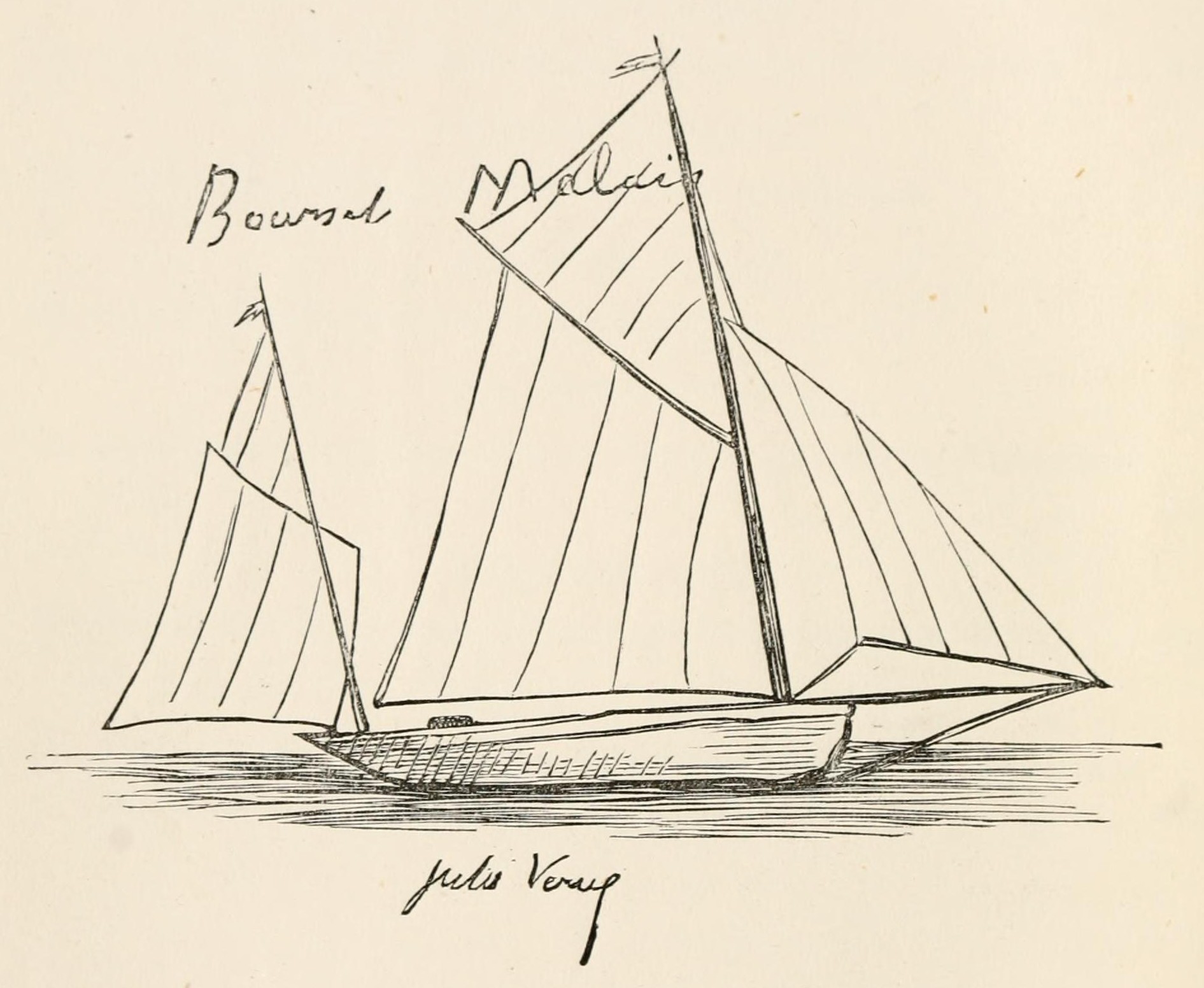

In 1867, Verne acquired a small boat, the Saint-Michel, which he successively replaced with the Saint-Michel II and the Saint-Michel III as his financial situation improved. He sailed around Europe on the Saint-Michel III. After his first novel, most of his stories were initially serialized in the Magazine d'Éducation et de Récréation, a biweekly Hetzel publication, before being released in book form. His brother Paul contributed to 40th French climbing of the Mont-Blanc and a collection of short stories - Doctor Ox - in 1874. Verne became both wealthy and famous.

His son, Michel Verne, married an actress against his father's wishes, had two children with an underage mistress, and accumulated significant debts. However, the relationship between father and son improved as Michel matured.

2.4. Later years

Though raised as a Roman Catholic, Verne gradually gravitated towards deism after 1870. Scholars suggest his novels often reflect a deist philosophy, frequently incorporating the notion of God or divine providence but rarely mentioning Christ.

On March 9, 1886, as Verne returned home, his twenty-six-year-old nephew, Gaston, shot at him twice with a pistol. The first bullet missed, but the second struck Verne's left leg, causing a permanent limp that could not be overcome. This incident was not widely publicized, and Gaston spent the rest of his life in a mental asylum.

Following the deaths of both his mother and Hetzel in 1886, Jules Verne's works began to take on a darker tone. In 1888, he entered politics, being elected town councillor of Amiens, where he championed several improvements and served for fifteen years.

Verne was made a knight of France's Legion of Honour on April 9, 1870, and subsequently promoted to Officer on July 19, 1892.

3. Works

Jules Verne's literary output was vast and diverse, though he is best known for his contributions to the Voyages extraordinaires series.

The largest body of Verne's work is the Voyages extraordinaires series, which encompasses nearly all of his novels, with the exceptions of two rejected manuscripts, Paris in the Twentieth Century and Backwards to Britain (published posthumously in 1994 and 1989, respectively), and projects left unfinished at his death (many of which were later adapted or rewritten by his son Michel for publication). Beyond these, Verne also wrote numerous plays, poems, song texts, operetta libretti, and short stories, along with a variety of essays and miscellaneous non-fiction works.

3.1. Major Novels

Verne's most famous novels are characterized by their adventurous plots, detailed scientific explanations, and often prophetic technological concepts.

- Five Weeks in a Balloon (Cinq semaines en ballonFrench, 1863): This novel, his first major success, details the journey of three British explorers across Africa in a hydrogen balloon, combining geographical exploration with scientific adventure. It established Verne's signature style of integrating factual information into a fictional narrative.

- Journey to the Center of the Earth (Voyage au centre de la TerreFrench, 1864): Follows a German professor, his nephew, and a guide as they descend into a volcanic tube, encountering prehistoric creatures and natural wonders on their way to the Earth's core.

- From the Earth to the Moon (De la Terre à la LuneFrench, 1865): Chronicles the efforts of a post-American Civil War gun club to build an enormous cannon to launch a projectile to the Moon. This novel, along with its sequel Around the Moon, is notable for its scientific accuracy in predicting aspects of space travel.

- The Adventures of Captain Hatteras (Les Aventures du capitaine HatterasFrench, 1864-1867): A tale of an English captain's relentless quest to reach the North Pole.

- In Search of the Castaways (Les Enfants du capitaine GrantFrench, 1866-1868): Follows a group searching for Captain Grant and his shipwrecked crew, leading them on a global adventure.

- Twenty Thousand Leagues Under the Seas (Vingt mille lieues sous les mersFrench, 1869): One of Verne's most iconic works, it introduces Captain Nemo and his advanced submarine, the Nautilus, as they explore the depths of the ocean, encountering various marine life and underwater landscapes.

- Around the World in Eighty Days (Le Tour du monde en quatre-vingts joursFrench, 1872): A classic adventure story about Phileas Fogg's ambitious wager to circumnavigate the globe in 80 days. Its fast-paced narrative and memorable characters made it an instant success.

- The Mysterious Island (L'Île mystérieuseFrench, 1874-1875): A sequel to Twenty Thousand Leagues Under the Seas and In Search of the Castaways, this novel tells the story of five Union prisoners of war who escape in a balloon and land on a deserted island, where they use their scientific knowledge to survive and thrive.

- Michael Strogoff (Michel StrogoffFrench, 1876): Set in Imperial Russia, this adventure novel follows a courier tasked with delivering a message across Siberia during a Tartar invasion.

Other notable novels include:

- A Floating City (Une ville flottanteFrench, 1871)

- The Fur Country (Le Pays des fourruresFrench, 1873)

- The Survivors of the Chancellor (Le ChancellorFrench, 1875)

- Off on a Comet (Hector ServadacFrench, 1877)

- The Child of the Cavern (Les Indes noiresFrench, 1877)

- Dick Sand, A Captain at Fifteen (Un capitaine de quinze ansFrench, 1878)

- The Begum's Fortune (Les Cinq Cents Millions de la BégumFrench, 1879)

- Tribulations of a Chinaman in China (Les Tribulations d'un Chinois en ChineFrench, 1879)

- The Steam House (La Maison à vapeurFrench, 1880)

- Eight Hundred Leagues on the Amazon (La JangadaFrench, 1881)

- Godfrey Morgan (L'École des RobinsonsFrench, 1882)

- The Green Ray (Le Rayon vertFrench, 1882)

- Kéraban the Inflexible (Kéraban-le-TêtuFrench, 1883)

- The Vanished Diamond (L'Étoile du sudFrench, 1884)

- The Archipelago on Fire (Archipel en feuFrench, 1884)

- Mathias Sandorf (Mathias SandorfFrench, 1885)

- The Lottery Ticket (Un billet de loterieFrench, 1886)

- Robur the Conqueror (Robur le conquérantFrench, 1886)

- North Against South (Nord contre SudFrench, 1887)

- The Flight to France (Le Chemin de FranceFrench, 1887)

- Two Years' Vacation (Deux ans de vacancesFrench, 1888)

- Family Without a Name (Famille-sans-nomFrench, 1889)

- The Purchase of the North Pole (Sans dessus dessousFrench, 1889)

- César Cascabel (César CascabelFrench, 1890)

- Mistress Branican (Mistress BranicanFrench, 1891)

- The Carpathian Castle (Le Château des CarpathesFrench, 1892)

- Claudius Bombarnac (Claudius BombarnacFrench, 1892)

- Foundling Mick (P'tit-BonhommeFrench, 1893)

- Captain Antifer (Mirifiques aventures de maître AntiferFrench, 1894)

- Propeller Island (L'Île à héliceFrench, 1895)

- Facing the Flag (Face au drapeauFrench, 1896)

- Clovis Dardentor (Clovis DardentorFrench, 1896)

- An Antarctic Mystery (Le Sphinx des glacesFrench, 1897)

- The Mighty Orinoco (Le Superbe OrénoqueFrench, 1898)

- The Will of an Eccentric (Le Testament d'un excentriqueFrench, 1899)

- The Castaways of the Flag (Seconde patrieFrench, 1900)

- The Village in the Treetops (Le Village aérienFrench, 1901)

- The Sea Serpent (Les Histoires de Jean-Marie CabidoulinFrench, 1901)

- The Kip Brothers (Les Frères KipFrench, 1902)

- Travel Scholarships (Bourses de voyageFrench, 1903)

- A Drama in Livonia (Un drame en LivonieFrench, 1904)

- Master of the World (Maître du MondeFrench, 1904)

- Invasion of the Sea (L'Invasion de la merFrench, 1905)

3.2. Short Stories and Other Works

Beyond his celebrated novels, Jules Verne produced a diverse range of short stories, plays, and other literary forms, demonstrating the breadth of his creative talent.

His short story collections include:

- Doctor Ox (Le Docteur OxFrench, 1874): This collection features several notable short stories, including "A Fantasy of Doctor Ox" (Une fantaisie du Docteur OxFrench, 1872), "Master Zacharius" (Maître Zacharius ou l'horloger qui avait perdu son âmeFrench, 1854), "A Drama in the Air" (Un drame dans les airsFrench, 1851), and "A Winter Amid the Ice" (Un hivernage dans les glacesFrench, 1855). It also included "The Fortieth French Ascent of Mont Blanc," a work with contributions from his brother, Paul Verne, which was later removed from revised editions.

- Yesterday and Tomorrow (Hier et demainFrench, 1910): A posthumously published collection, it includes "The Raton Family's Adventures" (Aventures de la famille RatonFrench, 1891), "Monsieur Ré-Dièze and Mademoiselle Mi-Bémol" (M. Re-Dièze et Mlle Mi-BémolFrench, 1893), "Jean Morénas" (La Destinée de Jean MorénasFrench, an early work with an unknown writing date), "The Humbug" (circa 1863, revised by his son Michel), "In the Year 2889" (Au XXXIXe siècle: La journée d'un journaliste américain en 2889French, also potentially a collaboration with Michel), and "The Eternal Adam" (L'Éternel AdamFrench, 1905, originally titled Edom).

- Nantes Manuscripts, Volume 3 (Manuscrits nantais, Volume 3French, 1991): This collection of previously unpublished novellas and short stories includes "A Priest in 1835" (Un prêtre en 1835French), "Jedediah Jamet" (Jédédias JametFrench), "The Siege of Rome" (Le siège de RomeFrench), "The Marriage of Mr. Anselm des Tilleuls" (Le mariage de M. Anselme des TilleulsFrench), "San Carlos" (San CarlosFrench), "Pierre-Jean" (Pierre-JeanFrench), and the unfinished first part of "Uncle Robinson" (L'Oncle RobinsonFrench, 1861).

Verne also wrote plays, including:

- The Broken Straws (Les Pailles rompuesFrench, 1850): His debut play, co-written with Alexandre Dumas fils.

- Journey Through the Impossible (Voyage à travers l'impossibleFrench, 1882): A fantasy play.

Several of his works were published posthumously, sometimes with significant revisions by his son, Michel Verne. These include:

- The Lighthouse at the End of the World (Le Phare du bout du mondeFrench, 1905): Published after his death, later original versions were released by the Jules Verne Society.

- The Barsac Mission (L'Étonnante Aventure de la Mission BarsacFrench, 1919): A work completed by Michel Verne, based on his father's ideas, which originally contained references to Esperanto, a language Jules Verne was keenly interested in.

- Paris in the Twentieth Century (Paris au XXe siècleFrench, 1994): Written in 1861 but rejected by Hetzel for its pessimistic outlook, this novel was discovered by Verne's great-grandson in 1989 and published in 1994.

- The Golden Volcano (Le Volcan d'orFrench, 1900): Published posthumously in a revised form in 1906, with the original version released in 1989.

- The Secret of Wilhelm Storitz (Le Secret de Wilhelm StoritzFrench, 1901): Published posthumously in a revised form in 1910, with the original version released in 1985.

- The Chase of the Golden Meteor (La Chasse au météoreFrench, 1901): Published posthumously in a revised form in 1908, with the original version released in 1986.

- The Danube Pilot (Le Pilote du DanubeFrench, 1908): Published posthumously.

4. Thought and Philosophy

Jules Verne's works are rich with underlying philosophical ideas, reflecting his views on scientific progress, societal issues, and human nature.

4.1. Views on Science, Technology, and Progress

Verne is often celebrated for his optimistic portrayal of scientific advancement and technological innovation. His novels frequently feature groundbreaking inventions-like the submarine Nautilus, various flying machines, and space cannons-that were fantastical for his time but later became reality. He meticulously researched contemporary scientific knowledge to lend realism to his narratives, making complex concepts accessible to a broad audience. This dedication led to the popular, though often exaggerated, perception of him as a "prophet" of scientific progress.

However, Verne himself repeatedly denied being a scientific prophet, stating, "I have invented nothing." He emphasized that his primary goal was to "depict the earth [and] at the same time to realize a very high ideal of beauty of style." For instance, he clarified that he wrote Five Weeks in a Balloon not as a story about ballooning, but as a story about Africa, using the balloon merely as a narrative device to transport his characters across the continent. He even admitted to having no faith in the possibility of steering balloons. He attributed any coincidences between scientific developments and his work to his extensive research, noting that he "always took numerous notes out of every book, newspaper, magazine, or scientific report that I came across."

Furthermore, while his published works often conveyed an optimistic view of technology, influenced by his publisher Hetzel, Verne harbored underlying critiques and concerns about its societal and human impact. His novel Paris in the Twentieth Century, rejected by Hetzel and published only posthumously, reveals a more pessimistic outlook on a future dominated by technology, where human life becomes complex and mundane despite advanced innovations. This demonstrates that Verne's perspective was more nuanced than a simple endorsement of progress, acknowledging potential downsides and the erosion of human happiness in a technologically driven world.

4.2. Pacifism and Social Critique

Verne's narratives often embed strong social commentary and anti-war sentiments, reflecting a perspective deeply concerned with justice and human dignity. Throughout his life, he consistently satirized and criticized war and military life. His personal aversion to military service was evident when he expressed great relief at being spared from conscription, writing to his father, "You should already know, dear papa, what I think of the military life, and of these domestic servants in livery. ... You have to abandon all dignity to perform such functions." These strong anti-war sentiments remained steadfast throughout his life, often to his father's dismay.

He was a vocal supporter of oppressed peoples, a theme powerfully embodied by characters like Captain Nemo in Twenty Thousand Leagues Under the Seas. Nemo, initially conceived as a Polish scientist seeking vengeance against the Russians for their actions during the January Uprising, was ultimately portrayed with a mysterious past at Hetzel's insistence, but his anti-slavery stance and fight against oppressors still resonated with readers. This reflected Verne's broader concern for human rights and his critical stance against imperialistic powers and social injustices. His works frequently featured characters who were victims of societal or political oppression, and his narratives often explored the consequences of unchecked power and the importance of liberation.

Verne also showed a critical view of the political landscape of his time, particularly his disapproval of Bonapartism and Napoleon III. His social critiques extended to the societal norms and expectations, as seen in his early life experiences, where he criticized Nantes society after his first love affair ended due to societal pressures. This critical lens, though sometimes softened in his published works due to editorial influence, remained a consistent element of his thought, highlighting his commitment to a more just and humane world.

5. Personal Life

Jules Verne's personal life was marked by significant relationships and events that shaped his character and influenced his literary output.

In May 1856, Verne traveled to Amiens to be the best man at a friend's wedding. There, he met Honorine Anne Hébée Morel (née du Fraysne de Viane), a 26-year-old widow with two young children. Verne was deeply attracted to her, and seeking a secure income to court her, he joined her brother's brokerage business. With his financial situation improving, he won Honorine's and her family's favor, and they married on January 10, 1857.

Their only biological son, Michel Verne, was born on August 3, 1861. The relationship between Jules and Michel was complex. Michel married an actress against his father's wishes, had two children with an underage mistress, and accumulated significant debts. Despite these early challenges, the father-son relationship improved as Michel matured. After Jules Verne's death, Michel oversaw the publication of several of his father's posthumous novels, though it was later discovered that Michel had made extensive changes to these stories. The original versions were eventually published by the Jules Verne Society at the end of the 20th century.

A traumatic incident occurred on March 9, 1886, when Verne was shot twice in the leg by his 26-year-old nephew, Gaston. The second bullet lodged in Verne's left leg, causing a permanent limp. This event was kept out of the media, and Gaston spent the remainder of his life in a mental asylum. This personal tragedy, along with the deaths of his mother and his publisher Hetzel in 1886, contributed to a darker tone in Verne's later works.

6. Reception and Legacy

Jules Verne's works have had a profound and multifaceted impact on literature, science, and popular culture, though his reception has varied significantly across different regions and historical periods.

6.1. Literary Reception and Influence

Following his debut with Hetzel, Verne was enthusiastically received in France by both writers and scientists. Early admirers included prominent figures like George Sand and Théophile Gautier. Notable contemporaries, from geographer Vivien de Saint-Martin to critic Jules Claretie, praised Verne and his works in critical and biographical notes.

However, Verne's increasing popularity among readers and playgoers, particularly due to the highly successful stage adaptation of Around the World in Eighty Days, led to a gradual shift in his literary reputation. As his novels and stage productions continued to sell commercially, many contemporary critics began to view him as merely a genre-based storyteller, rather than a serious author deserving of academic study. This denial of formal literary status manifested in various forms, including dismissive criticism from writers such as Émile Zola and the notable absence of Verne's nomination for membership in the Académie Française. Verne himself acknowledged this critical dismissal, stating in a later interview, "The great regret of my life is that I have never taken any place in French literature." To Verne, who considered himself "a man of letters and an artist, living in the pursuit of the ideal," this critical neglect based on literary ideology was the ultimate snub.

This perception of Verne as a popular genre writer, yet a critical persona non grata, persisted after his death. Early biographies, including one by his niece Marguerite Allotte de la Fuÿe, often presented error-filled and embellished hagiographies rather than focusing on his actual working methods or literary output. Simultaneously, sales of Verne's original unabridged novels declined significantly even in France, replaced by abridged versions aimed directly at children.

Despite this, the decades following Verne's death saw the rise of the "Jules Verne cult" in France-a growing group of scholars and young writers who took his works seriously as literature and acknowledged his influence on their own pioneering works. Some members of this cult founded the Société Jules Verne, the first academic society dedicated to Verne scholars. Many others became highly respected avant-garde and surrealist literary figures in their own right. Their praise and analyses, emphasizing Verne's stylistic innovations and enduring literary themes, proved highly influential for future literary studies.

In the 1960s and 1970s, Verne's reputation in France soared, largely thanks to a sustained wave of serious literary study by renowned French scholars and writers. Roland Barthes' seminal essay Nautilus et Bateau Ivre (The Nautilus and the Drunken Boat) was particularly influential in its exegesis of the Voyages extraordinaires as a purely literary text. Book-length studies by figures such as Marcel Moré and Jean Chesneaux examined Verne from various thematic perspectives. French literary journals dedicated entire issues to Verne's work, featuring essays by influential figures like Michel Butor, Michel Foucault, and René Barjavel. Concurrently, Verne's entire published opus returned to print, with unabridged and illustrated editions released by Livre de Poche and Éditions Rencontre. This resurgence culminated in Verne's sesquicentennial year, 1978, when he was the subject of an academic colloquium at the Centre culturel international de Cerisy-la-Salle, and Journey to the Center of the Earth was accepted for the French university system's agrégation reading list. Since these events, Verne has been consistently recognized in Europe as a legitimate member of the French literary canon, with academic studies and new publications continuing steadily.

6.2. Role in Science Fiction

The relationship between Verne's Voyages extraordinaires and the literary genre of science fiction is complex. Verne is frequently cited as one of the genre's founders, and his profound influence on its development is undeniable. However, earlier writers such as Lucian of Samosata, Voltaire, and Mary Shelley have also been credited with creating science fiction, reflecting the genre's evolving definition and history.

A central point of discussion is whether Verne's works inherently qualify as science fiction. Maurice Renard claimed that Verne "never wrote a single sentence of scientific-marvelous." Verne himself repeatedly asserted in interviews that his novels were not intended to be read as purely scientific, stating, "I have invented nothing." His personal objective was to "depict the earth [and] at the same time to realize a very high ideal of beauty of style." He clarified that he wrote Five Weeks in a Balloon not as a story about ballooning, but as a story about Africa, using the balloon as a means to transport his characters. He even admitted that at the time of writing, he had no faith in the possibility of ever steering balloons.

Closely tied to his science fiction reputation is the often-repeated claim that he was a "prophet" of scientific progress, whose novels featured technologies that were fantastical in his day but later became commonplace. While these claims have a long history, particularly in America, modern scholarly consensus suggests they are heavily exaggerated. In a 1961 article critiquing the scientific accuracy of Twenty Thousand Leagues Under the Seas, Theodore L. Thomas speculated that Verne's storytelling skill and readers' faulty memories led people to "remember things from it that are not there. The impression that the novel contains valid scientific prediction seems to grow as the years roll by." Verne himself flatly denied being a futuristic prophet, attributing any connection between scientific developments and his work to "mere coincidence" and his extensive research: "even before I began writing stories, I always took numerous notes out of every book, newspaper, magazine, or scientific report that I came across."

Despite his own disclaimers, Verne's meticulous research, vivid imagination, and focus on technological possibilities undoubtedly laid significant groundwork for the science fiction genre, inspiring countless future authors and scientists.

6.3. English Translations and Their Impact

The translation of Verne's works into English began in 1852 with Anne T. Wilbur's translation of his short story A Voyage in a Balloon (1851), published in the American journal Sartain's Union Magazine of Literature and Art. Novel translations commenced in 1869 with William Lackland's rendition of Five Weeks in a Balloon (1863) and continued steadily throughout Verne's lifetime. Publishers and translators often worked hastily to capitalize on his most lucrative titles in English-speaking markets. Unlike Hetzel, who aimed his Voyages extraordinaires at all ages, British and American publishers primarily marketed Verne's books to young audiences. This business decision had a lasting impact on Verne's reputation in English-speaking countries, leading him to be perceived almost exclusively as a children's author.

These early English translations have been widely criticized for extensive textual omissions, errors, and alterations, and are not considered accurate representations of Verne's original novels. British writer Adam Roberts commented in The Guardian: "I'd always liked reading Jules Verne and I've read most of his novels; but it wasn't until recently that I really understood I hadn't been reading Jules Verne at all... It's a bizarre situation for a world-famous writer to be in. Indeed, I can't think of a major writer who has been so poorly served by translation." Similarly, American novelist Michael Crichton observed that Verne's "prose is lean and fast-moving in a peculiarly modern way," but he "has been particularly ill-served by his English translators. At best they have provided us with clunky, choppy, tone-deaf prose. At worst - as in the notorious 1872 'translation' [of Journey to the Center of the Earth] published by Griffith & Farran - they have blithely altered the text, giving Verne's characters new names, and adding whole pages of their own invention, thus effectively obliterating the meaning and tone of Verne's original."

Since 1965, a considerable number of more accurate English translations of Verne's works have appeared. However, the older, deficient translations continue to be republished due to their public domain status and easy availability, especially in online sources, perpetuating the misrepresentation of his work.

6.4. Modern Reinterpretation and Cultural Impact

Jules Verne's novels have had a wide-ranging influence on both literary and scientific endeavors. Writers known to have been influenced by Verne include Marcel Aymé, Roland Barthes, René Barjavel, Michel Butor, Blaise Cendrars, Paul Claudel, Jean Cocteau, Julio Cortázar, François Mauriac, Rick Riordan, Raymond Roussel, Claude Roy, Antoine de Saint-Exupéry, and Jean-Paul Sartre. Scientists and explorers who acknowledged Verne's inspiration include Richard E. Byrd, Yuri Gagarin, Simon Lake, Hubert Lyautey, Guglielmo Marconi, Fridtjof Nansen, Konstantin Tsiolkovsky, Wernher von Braun, and Jack Parsons. Ray Bradbury summarized Verne's global influence on literature and science, stating, "We are all, in one way or another, the children of Jules Verne."

Verne is also credited with helping inspire the steampunk genre, a literary and social movement that romanticizes science fiction based on 19th-century technology. His imaginative depictions of Victorian-era inventions and adventures laid much of the groundwork for this aesthetic.

His stories have been extensively adapted and reinterpreted across various media, including film, television, and video games, cementing his enduring influence on popular culture. Examples include:

- Film adaptations**: Numerous films have been made based on his works, such as the 1954 Disney adaptation of Twenty Thousand Leagues Under the Seas and the 1956 film Around the World in Eighty Days.

- Theme Parks**: Tokyo DisneySea's "Mysterious Island" theme port is based on Twenty Thousand Leagues Under the Seas and The Mysterious Island, featuring Captain Nemo's secret base.

- Space Exploration**: The first European Space Agency Automated Transfer Vehicle (ATV), launched in March 2008, was named Jules Verne in his honor, carrying supplies to the International Space Station.

- Google Doodle**: On February 8, 2011, to celebrate his 183rd birthday, Google's search logo was transformed into an interactive doodle inspired by Twenty Thousand Leagues Under the Seas.

His characters, such as Captain Nemo from Twenty Thousand Leagues Under the Seas and Phileas Fogg from Around the World in Eighty Days, have transcended their literary origins to become cultural icons. Even in the 21st century, Verne's works continue to be a source of common cultural reference and inspiration.

7. Death

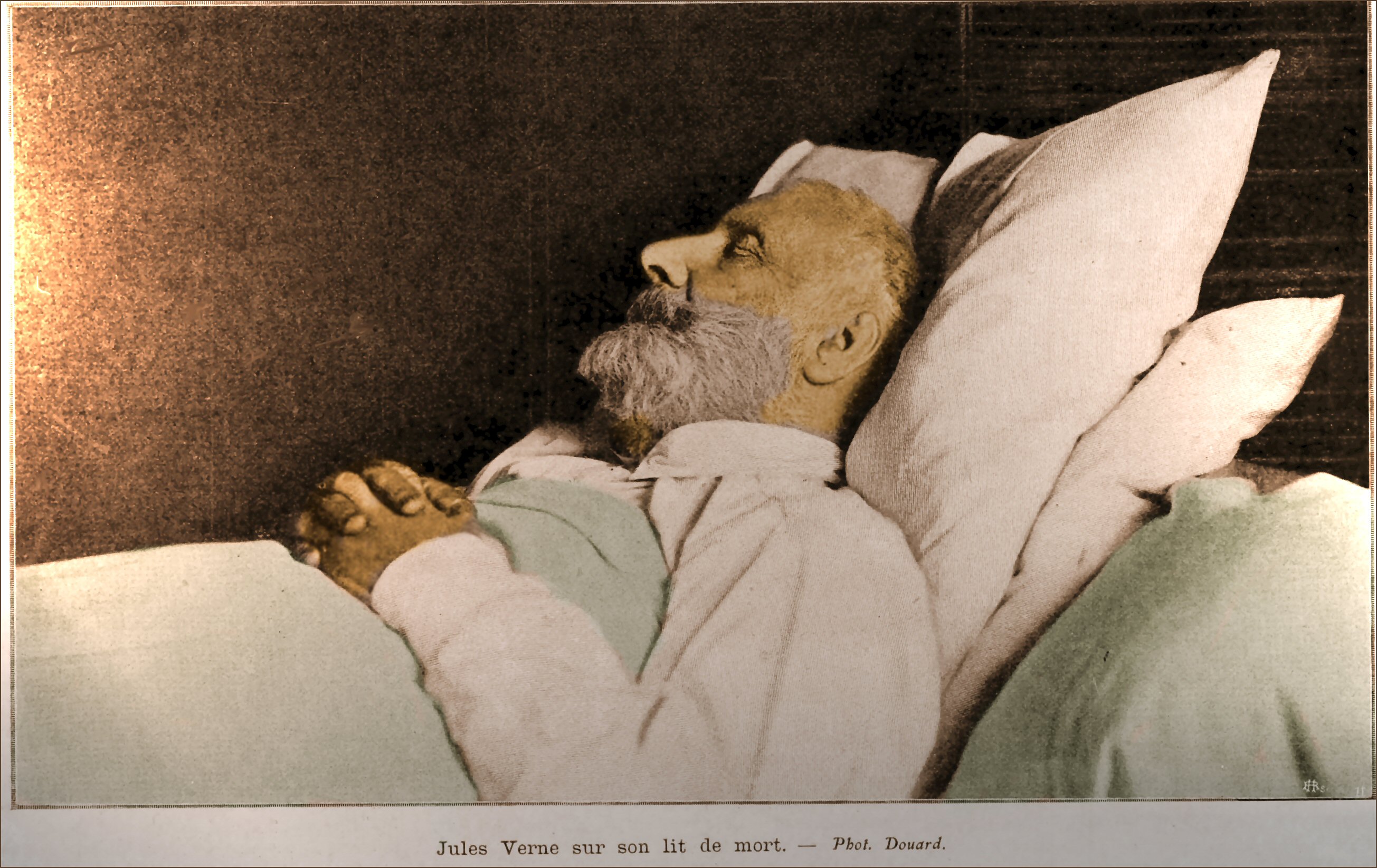

Jules Verne's final years were marked by declining health and continued literary output, albeit with a darker thematic turn.

On March 24, 1905, while suffering from chronic diabetes and complications from a stroke that had paralyzed his right side, Verne died at his home in Amiens, located at 44 Boulevard Longueville (now Boulevard Jules-Verne). His son, Michel Verne, took on the responsibility of overseeing the publication of his father's remaining manuscripts, including the novels Invasion of the Sea and The Lighthouse at the End of the World. The Voyages extraordinaires series continued to be published at a rate of two volumes per year for several years after his death.

It was later discovered that Michel Verne had made extensive changes to these posthumously published stories, altering plots and themes. The original, unedited versions of these works were eventually published at the end of the 20th century by the Jules Verne Society (Société Jules Verne).

In 1919, Michel Verne published The Barsac Mission (L'Étonnante Aventure de la Mission BarsacFrench), whose initial drafts contained references to Esperanto, a language in which Jules Verne had shown great interest. Verne had even promised to write a novel in Esperanto, intending to promote the international language among young people, but he passed away before fulfilling this wish. The planned title for this unfinished Esperanto novel was Voyage d'étude, where Esperanto was to play a central role, with a character stating, "Esperanto is certainly the fastest means of spreading civilization... The common language of humanity lost in the legend of the Tower of Babel can only be rediscovered through the use of Esperanto."

In 1989, Verne's great-grandson made a significant discovery: his ancestor's previously unpublished novel, Paris in the Twentieth Century. This manuscript, which Hetzel had rejected decades earlier due to its pessimistic view of a technologically advanced future, was subsequently published in 1994, offering new insights into Verne's more critical and satirical perspectives.

Verne was buried in the Madeleine Cemetery in Amiens. Boulevard Longueville, where he resided, was later renamed Boulevard Jules-Verne in his honor.

8. Related Topics

- List of Legion of Honour recipients by name (V)

- Scientific Marvelous

- Michel Verne (son)

- Maison de Jules Verne (Jules Verne House), his former home in Amiens, now a museum.

- Jules Verne Museum in Nantes, his hometown, dedicated to his works and life.

- Jules Verne Awards

- Jules Verne Trophy - a prize for the fastest circumnavigation of the world by any type of yacht.

- Jules Verne ATV - the first Automated Transfer Vehicle of the European Space Agency.

- Jules Verne lunar crater - a crater on the Moon named after him.

- Mysterious Island - a themed land at Tokyo DisneySea inspired by his novels.

- Piotr Kropotkin - a Russian anarchist who admired Verne's work.

- Léon Benett - a French illustrator who frequently illustrated Verne's works.

- Index Translationum - UNESCO's database of translated books, which lists Verne as one of the most translated authors.