1. Overview

Rear Admiral Richard Evelyn Byrd Jr. was a distinguished American naval officer, pioneering aviator, and polar explorer, whose expeditions significantly advanced scientific understanding and technological capabilities in the early 20th century. He is celebrated for his ambitious aerial explorations, including claims of being the first to reach both the North Pole and South Pole by air, though his North Pole claim remains a subject of considerable debate. Byrd's contributions extended beyond mere exploration; he was instrumental in organizing complex polar logistics, establishing permanent research bases in Antarctica, and pushing the boundaries of aviation technology. His work laid foundational knowledge for future scientific endeavors in the polar regions, highlighting the importance of international cooperation and technological innovation in understanding the Earth's extreme environments.

2. Early Life and Family Background

Richard Evelyn Byrd Jr. was born on October 25, 1888, in Winchester, Virginia, into a family deeply rooted in American history. His upbringing provided a foundation for his adventurous spirit and later career in exploration.

2.1. Ancestry and Family

Byrd was the son of Esther Bolling (Flood) and Richard Evelyn Byrd Sr., who served as Speaker of the Virginia House of Delegates. His lineage traced back to some of the most prominent First Families of Virginia. Notable ancestors included the planter John Rolfe and his wife Pocahontas, William Byrd II of Westover Plantation, who was instrumental in establishing Richmond, Virginia, as well as William Byrd I, and Robert "King" Carter, a colonial governor. He was also a descendant of George Yeardley, Francis Wyatt, and Samuel Argall. Richard E. Byrd Jr. was the brother of Harry F. Byrd, who became a dominant figure in the Virginia Democratic Party from the 1920s to the 1960s, serving as Governor of Virginia and later as a U.S. Senator.

2.2. Marriage and Children

On January 20, 1915, Richard E. Byrd married Marie Ames Byrd, who passed away in 1974. Their union resulted in four children: Richard Evelyn Byrd III, Evelyn Bolling Byrd Clarke, Katharine Agnes Byrd Breyer, and Helen Byrd Stabler. In a tribute to his wife, Byrd named a region of Antarctic land he discovered "Marie Byrd Land" after her. Additionally, he named a mountain range, the Ames Range, after her father, a wealthy industrialist who had purchased their large brownstone house at 9 Brimmer Street in Boston's fashionable Beacon Hill neighborhood, where the Byrd family moved in late 1924.

2.3. Personal Life

Beyond his public achievements, Byrd maintained significant personal relationships and had a notable companion. He was friends with Edsel Ford and his father, Henry Ford, whose admiration for Byrd's polar exploits led to significant sponsorship and financing from the Ford Motor Company for his various expeditions. A cherished aspect of his personal life was his pet dog, Igloo, a Fox Terrier, who accompanied Byrd on both his North and South Pole expeditions. Igloo is buried at the Pine Ridge Pet Cemetery with a tombstone bearing the inscription, "He was more than a friend."

4. Aviation Achievements

Byrd's post-World War I career was marked by his pioneering efforts in aviation, pushing the boundaries of flight and contributing significantly to aerial exploration.

4.1. Post-WWI Aviation Activities

After World War I, Byrd volunteered for the U.S. Navy's 1919 aerial transatlantic crossing, the first time the Atlantic Ocean was traversed by an aircraft. Despite his desire to be a crew member, his prior overseas service in Newfoundland precluded him from direct participation. Nevertheless, his expertise in aerial navigation was invaluable, leading to his appointment to plan the mission's flight path. Of the three flying boats that departed Newfoundland (NC-1, NC-3, and NC-4), only Lieutenant Commander Albert Cushing Read's NC-4 successfully completed the journey on May 18, 1919, marking the first transatlantic flight.

In 1921, Byrd aimed to attempt a solo nonstop crossing of the Atlantic, predating Charles Lindbergh's flight. However, then-acting Secretary of the Navy Theodore Roosevelt Jr. deemed the risks too high, preventing Byrd from undertaking the flight. Byrd was subsequently assigned to the dirigible ZR-2 (formerly the British R-38), but a twist of fate saved him: he missed his train to the airship on August 24, 1921. The airship tragically broke apart mid-air, killing 44 of 49 crew members. The accident deeply affected Byrd, who lost several friends and was involved in the recovery and investigation. This experience instilled in him a lifelong commitment to prioritizing safety in all future expeditions.

Due to post-World War I Navy reductions, Byrd reverted to the rank of lieutenant at the end of 1921. In the summer of 1923, he and a group of volunteer Navy veterans helped establish the Naval Reserve Air Station (NRAS) at Squantum Point near Boston. This station, commissioned on August 15, 1923, utilized a disused World War I seaplane hangar and is considered the first air base in the Naval Reserve program.

From June to October 1925, Byrd commanded the aviation unit of the Arctic expedition to North Greenland led by Donald B. MacMillan. Although the expedition did not reach the pole, Byrd's efforts and the aviation element's successful contributions significantly enhanced his reputation as a pioneer of aircraft in exploration. During this expedition, Byrd befriended Navy Chief Aviation Pilot Floyd Bennett and Norwegian pilot Bernt Balchen, both of whom would become crucial to his future endeavors. Bennett served as pilot for Byrd's North Pole flight the following year, while Balchen, whose knowledge of Arctic flight operations proved invaluable, was the primary pilot on Byrd's South Pole flight in 1929.

4.2. 1927 Trans-Atlantic Flight

In 1927, Byrd announced his intention to compete for the Orteig Prize, aiming to complete the first nonstop flight between the United States and France. He secured backing from the American Trans-Oceanic Company, founded in 1914 by department-store magnate Rodman Wanamaker to develop aircraft for transatlantic flights.

Byrd again selected Floyd Bennett as his chief pilot, with Norwegian Bernt Balchen, Bert Acosta, and Lieutenant George Otto Noville as additional crew members. During a practice takeoff, the Fokker Trimotor aircraft, named America, crashed with Anthony Fokker at the controls and Bennett as co-pilot. Bennett was severely injured, and Byrd sustained minor injuries. While the America was undergoing repairs, Charles Lindbergh successfully completed his historic solo flight on May 21, 1927, winning the Orteig Prize. (Coincidentally, Lindbergh had applied to serve as a pilot on Byrd's North Pole expedition in 1925, but his application was too late.)

Despite Lindbergh's success, Byrd pressed on with his transatlantic quest. Balchen replaced the still-recovering Bennett as chief pilot. On June 29, 1927, Byrd, Balchen, Acosta, and Noville departed from Roosevelt Field, East Garden City, New York, aboard the America. The flight carried mail from the US Postal Service to demonstrate the practicality of airmail. The following day, cloud cover over France prevented them from landing in Paris. They returned to the coast of Normandy and successfully crash-landed near the beach at Ver-sur-Mer (which would later become Gold Beach during the Normandy Invasion on June 6, 1944) on July 1, 1927, with no fatalities. In France, Byrd and his crew were hailed as heroes, and Byrd was invested as an Officer of the French Legion of Honor by Prime Minister Raymond Poincare on July 6.

Upon their return to the United States, a celebratory dinner was held in their honor in New York City on July 19. At this event, Byrd and Noville were awarded the Distinguished Flying Cross by Secretary of the Navy Curtis D. Wilbur. Acosta and Balchen, being civilians at the time, were not eligible for this military decoration. In an article for the August 1927 edition of Popular Science Monthly, Byrd accurately predicted that while specially modified aircraft with small crews would achieve nonstop transatlantic flights, it would take another 20 years for such flights to become commercially viable.

5. Polar Exploration

Richard E. Byrd's legacy is most significantly defined by his extensive and pioneering explorations of the Arctic and Antarctic regions, which yielded crucial scientific data and expanded geographical knowledge.

5.1. Arctic Exploration

Byrd's involvement in Arctic exploration began with the 1925 MacMillan expedition, where his command of the aviation unit underscored the potential of aircraft in polar environments. This experience set the stage for his more ambitious and controversial North Pole flight.

5.1.1. 1926 North Pole Flight

On May 9, 1926, Richard Byrd and Navy Chief Aviation Pilot Floyd Bennett embarked on an attempt to fly over the North Pole. Their aircraft was a Fokker F.VIIa/3m tri-motor monoplane named Josephine Ford, after the daughter of Ford Motor Company president Edsel Ford, who, along with John D. Rockefeller Jr., provided significant financial backing for the expedition. The flight departed from Spitsbergen (Svalbard) and returned to the same airfield, lasting 15 hours and 57 minutes, including 13 minutes spent circling at their Farthest North. Byrd and Bennett claimed to have reached the North Pole, covering a distance of 1.54 K mile (1,335 nautical miles).

Upon his return to the United States from the Arctic, Byrd was celebrated as a national hero. He was honored with a ticker-tape parade in New York City, and on December 21, 1926, Congress passed a special act promoting him to the rank of commander and awarding both him and Floyd Bennett the Medal of Honor. The Josephine Ford aircraft was subsequently flown around the country as part of the celebrations. Bennett was promoted to the warrant officer rank of machinist. Byrd and Bennett received their Tiffany Cross versions of the Medal of Honor from President Calvin Coolidge at the White House on March 5, 1927.

Since 1926, Byrd's claim of reaching the North Pole has been a subject of intense debate and controversy. In 1958, Norwegian-American aviator and explorer Bernt Balchen expressed doubts, citing his knowledge of the aircraft's speed. Balchen further claimed that Bennett had confessed to him, months after the flight, that they had not actually reached the pole. Bennett, who had not fully recovered from an earlier crash, developed pneumonia after participating in a rescue flight for downed German aviators in Greenly Island, Canada, leading to his death on April 25, 1928. However, before his death, Bennett had begun a memoir, given numerous interviews, and written an article for an aviation magazine, all of which corroborated Byrd's account of the flight.

The release of Byrd's diary from the May 9, 1926, flight in 1996 fueled the controversy. The diary contained erased (but still legible) sextant readings that sharply differed from his later official report to the National Geographic Society. For instance, a sextant reading of the Sun at 7:07:10 GCT in his erased diary showed an apparent solar altitude of 19°25'30", while his official typescript reported the same reading as 18°18'18". Based on this and other diary data, researcher Dennis Rawlins concluded that Byrd maintained an accurate course but turned back approximately 80% of the way to the pole due to an engine oil leak, later falsifying his official report to support his claim of reaching the pole.

A defense of Byrd's claim posits a westerly-moving anticyclone that provided a tailwind, boosting his ground speed on both the outward and inward legs, thereby allowing the stated distance to be covered in the reported time. This theory, however, relies on rejecting the handwritten sextant data in favor of the typewritten alleged dead-reckoning data. Rawlins has challenged this, noting that the sextant data in the original official typewritten report were all expressed to 1 second, a level of precision not possible with Navy sextants of 1926 and inconsistent with the normal precision (half or quarter of a minute of arc) found in Byrd's diaries from 1925 and the 1926 flight.

If Byrd and Bennett did not reach the North Pole, then the first confirmed flight over the pole occurred just a few days later, on May 12, 1926. This was achieved by the airship Norge, which flew nonstop from Spitsbergen (Svalbard) to Alaska with a crew that included Roald Amundsen, Umberto Nobile, Oscar Wisting, and Lincoln Ellsworth. The majority opinion among polar experts today is that Amundsen was the first to reach both poles.

5.2. Antarctic Expeditions

Byrd's most extensive and impactful explorations were conducted in Antarctica, where he led multiple expeditions, making significant geographical discoveries and establishing crucial scientific bases.

5.2.1. First Antarctic Expedition (1928-1930)

In 1928, Byrd launched his first expedition to the Antarctic, a large-scale undertaking involving two ships and three airplanes. His flagship was the City of New York (a Norwegian sealing ship previously named Samson), and the second ship was the Eleanor Bolling (named after Byrd's mother). The expedition's aircraft included a Ford Trimotor named the Floyd Bennett (in honor of his recently deceased pilot), a Fairchild FC-2W2, NX8006, built in 1928, named Stars And Stripes (now displayed at the National Air and Space Museum's Steven F. Udvar-Hazy Center), and a Fokker Super Universal monoplane called the Virginia (after Byrd's home state). A base camp, "Little America", was established on the Ross Ice Shelf, serving as the hub for scientific expeditions conducted by snowshoe, dog sled, snowmobile, and airplane. To engage youth in Arctic exploration, 19-year-old American Boy Scout Paul Siple was selected to accompany the expedition. Siple later earned a doctorate and was likely the only person, besides Byrd himself, to participate in all five of Byrd's Antarctic expeditions.

Throughout that first Antarctic summer, extensive photographic and geological surveys were carried out, with continuous radio communications maintained with the outside world. After their initial winter, expeditions resumed. On November 28, 1929, the historic first flight to the South Pole and back was launched. Byrd, along with pilot Bernt Balchen, co-pilot/radioman Harold June, and photographer Ashley McKinley, flew the Floyd Bennett to the South Pole and back in 18 hours and 41 minutes. They encountered difficulties gaining sufficient altitude over the Polar Plateau and had to jettison empty gas tanks and emergency supplies to reach the necessary height, but ultimately succeeded. Byrd strongly advocated for ski-equipped aircraft, despite the considerable operational, logistical, and maintenance challenges they posed, which necessitated the establishment of significant onshore bases.

In recognition of this achievement, Byrd was promoted to the rank of rear admiral by a special act of Congress on December 21, 1929. At 41 years old, this made him the youngest admiral in the history of the United States Navy. For comparison, none of his Annapolis classmates achieved admiral rank until 1942, after 30 years of commissioned service. He is one of only four individuals, including Admiral David Dixon Porter, Arctic explorer Rear Admiral Donald Baxter MacMillan, and Rear Admiral Frederic R. Harris, to have been promoted to rear admiral in the U.S. Navy without first holding the rank of captain.

Following another summer of exploration, the expedition returned to North America on June 18, 1930. Unlike the 1926 flight, this expedition was honored with the gold medal of the American Geographical Society. The journey was also chronicled in the film With Byrd at the South Pole (1930).

Byrd, by then an internationally recognized pioneer in American polar exploration and aviation, served as Honorary National President of Pi Gamma Mu, the international honor society in the social sciences, from 1931 to 1935. He carried the society's flag during his first Antarctic expedition, symbolizing the spirit of adventure into the unknown that characterizes both natural and social sciences. To secure funding and political and public support for his expeditions, Byrd actively cultivated relationships with influential figures such as President Franklin Roosevelt, Henry Ford, Edsel Ford, John D. Rockefeller Jr., and Vincent Astor. As a gesture of gratitude, he named several geographic features in the Antarctic after his supporters.

5.2.2. Second Antarctic Expedition (1933-1934)

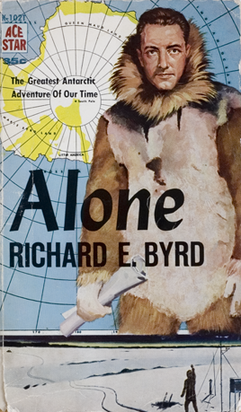

Byrd's second expedition, conducted during the Antarctic summer of 1933-1934 (winter in the Northern Hemisphere), is notable for his solitary five-month stay at Advance Base, a meteorological station. During this period, he narrowly escaped death from carbon monoxide poisoning due to a poorly ventilated stove. Unusual radio transmissions from Byrd eventually alarmed the men at the main base camp, prompting rescue attempts. The first two attempts failed due to darkness, heavy snow, and mechanical issues. Finally, Thomas Poulter, E. J. Demas, and Amory Waite reached Advance Base, finding Byrd in critical physical condition. The rescue party remained at Advance Base until October 12, when an airplane from the base camp evacuated Dr. Poulter and Byrd. The remaining men returned to the base camp with the tractor. Byrd vividly chronicled this harrowing experience in his autobiography, Alone. During the long Antarctic summer days, Byrd fashioned a large calendar on the wall of his exploration headquarters, crossing off each passing day.

A CBS radio station, KFZ, was established on the base camp ship, the Bear of Oakland. The program, The Adventures of Admiral Byrd, was short-waved to Buenos Aires and then relayed to New York. Sponsored by General Foods, these broadcasts aired on Saturday nights at 10:00 pm, reaching an average audience of 19.1 million and ranking #16 on the Hooper rating for the 1933-34 broadcast season.

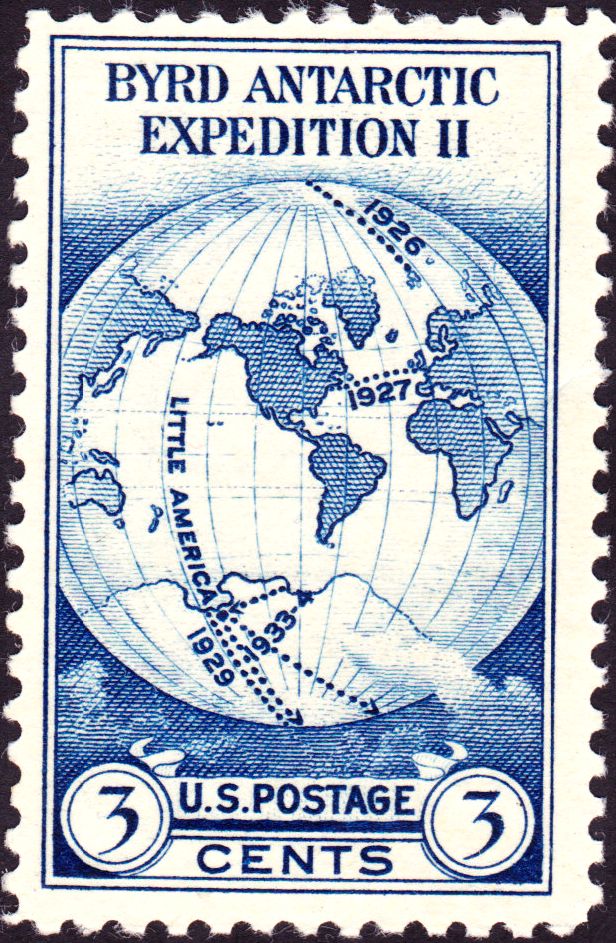

Byrd's Antarctic expedition also prompted President Roosevelt and the United States Postmaster General to honor the event with a U.S. commemorative stamp in 1933. This initiative significantly aided in raising funds for Byrd's expedition. The expedition, through the Post Office, sold philatelic subscription Philatelic covers to be serviced at the official USPOD post office set up at the Antarctic exploration base, dubbed Little America, which was officially established on October 6, 1933. All mail sent to Antarctica required at least one Byrd II 3 cent stamp, along with sufficient postage totaling 53 cents. The postage stamp is numbered 753 in the Scott's Catalog. The U.S. Post Office contracted with the expedition for this purpose, as it had no other means to deliver mail to and from Antarctica. Approximately 150,000 pieces of such mail passed through the special Antarctic post office between 1933 and 1934. Charles F. Anderson, a special representative of the Postmaster General, was assigned to the post office at Little America to handle postmarking and mail, as only postal members were authorized for these duties.

In late 1938, Byrd visited Hamburg and received an invitation to participate in the 1938/1939 German "Neuschwabenland" Antarctic Expedition, but he declined.

5.2.3. Antarctic Service Expedition (1939-1940)

Byrd's third expedition, officially known as the United States Antarctic Service Expedition, marked a significant shift as it was the first one fully financed and conducted by the United States government. The expedition's objectives included extensive studies in geology, biology, meteorology, and further exploration of the Antarctic continent. A notable piece of equipment brought along was the innovative Antarctic Snow Cruiser, though it unfortunately broke down shortly after its arrival.

Within a few months of the expedition's start, in March 1940, Byrd was recalled to active duty in the Office of the Chief of Naval Operations. The expedition continued its work in Antarctica without him until the last of its participants departed on March 22, 1941.

5.2.4. Operation Highjump (1946-1947)

In 1946, Secretary of the Navy James Forrestal appointed Byrd as the officer in charge of the Antarctic Developments Project. Byrd's fourth Antarctic expedition was code-named Operation Highjump. This was the largest Antarctic expedition to date, initially planned to last 6 to 8 months.

The expedition was supported by a substantial naval force, designated Task Force 68, under the command of Rear Admiral Richard H. Cruzen. This armada comprised thirteen US Navy support ships, including the flagship USS Mount Olympus (AGC-8) and the aircraft carrier USS Philippine Sea (CV-47), along with six helicopters, six flying boats, two seaplane tenders, and 15 other aircraft. The total personnel involved exceeded 4,000.

The fleet arrived in the Ross Sea on December 31, 1946, and conducted extensive aerial explorations covering an area half the size of the United States, during which 10 new mountain ranges were discovered and recorded. The primary focus of their survey was the eastern coastline of Antarctica, spanning from 150°E to the Greenwich meridian.

Admiral Byrd was interviewed by Lee van Atta of International News Service aboard the expedition's command ship, USS Mount Olympus. In this interview, which appeared in the Chilean newspaper El Mercurio on March 5, 1947, Byrd discussed the lessons learned from the operation. He notably warned that "the United States should adopt measures of protection against the possibility of an invasion of the country by hostile planes coming from the polar regions." He clarified that he was not trying to incite fear, but emphasized the "cruel reality" that in a future conflict, the United States could be attacked by planes flying over one or both poles. Byrd stated that the most significant outcome of his observations and discoveries was their potential impact on U.S. security, highlighting that "the fantastic speed with which the world is shrinking" was a key lesson from his recent Antarctic exploration. He urged his compatriots to recognize that "the time has ended when we were able to take refuge in our isolation and rely on the certainty that the distances, the oceans, and the poles were a guarantee of safety."

In 1948, the U.S. Navy produced a documentary about Operation Highjump titled The Secret Land. The film, which combined live-action footage with some re-enacted scenes, won the Academy Award for Best Documentary. On December 8, 1954, Byrd appeared on the television show Longines Chronoscope, where he was interviewed by Larry LeSueur and Kenneth Crawford. During this interview, he predicted that Antarctica would become the most important place in the world for science in the future.

5.2.5. Operation Deep Freeze I (1955-1956)

As part of the multinational collaboration for the International Geophysical Year (IGY) 1957-58, Byrd was appointed as the officer in charge of the U.S. Navy Operation Deep Freeze I in 1955-56. This operation was crucial for establishing permanent Antarctic bases at McMurdo Sound, the Bay of Whales, and the South Pole. This marked Byrd's final trip to Antarctica and the beginning of a sustained U.S. military presence on the continent. Byrd spent only one week in Antarctica during this expedition, commencing his return to the United States on February 3, 1956.

6. World War II Service

During World War II, Richard E. Byrd was recalled to active duty, serving in key advisory and special mission roles that contributed significantly to the American war effort.

On March 26, 1942, Byrd was recalled to active duty and served as a confidential advisor to Admiral Ernest J. King. From 1942 to 1945, he was a member of the South Pacific Island Base Inspection Board, which surveyed bases in the South Pacific during May and June 1942. The Board's report detailed conditions at each base, analyzed lessons learned in planning and equipping them, and provided recommendations for both individual bases and future advanced base planning.

On September 1, 1943, following directives from the President to the Secretary of the Navy, Byrd was ordered by the Commander-in-Chief United States Fleet and Chief of Naval Operations to lead a survey and "investigation of certain islands in the East and South Pacific in connection with national defense and commercial air bases and routes." The Special Navy Mission, with Byrd at its head, sailed from Balboa, Canal Zone, on USS Concord, commanded by Captain Irving Reynold Chambers, in September 1943. A tragic explosion at sea on October 7, 1943, caused by the ignition of gasoline fumes at the ship's stern, resulted in the deaths of 24 Concord crewmen, including the executive officer, Commander Rogers Elliott. Some men were thrown overboard, while others died from concussion, burns, fractured skulls, and broken necks. Several sailors displayed heroism while attempting to save their shipmates. The deceased were buried at sea on October 8. On October 23, 1943, from Nuku Hiva (the largest of the Marquesas Islands in French Polynesia), Byrd wrote a letter to Captain Chambers, commending him and his crew for their "courage and efficiency" following the explosion, stating it made him "feel proud to be an American. Great heroism was displayed, especially by the men who lost their lives rescuing the wounded." Byrd completed the Special Mission in December and subsequently participated in the United States Strategic Bombing Survey (USSBS) from 1944 to 1945.

On February 10, 1945, Byrd received the Order of Christopher Columbus from the government of the Dominican Republic. He was present at the Japanese surrender in Tokyo Bay on September 2, 1945. Byrd was released from active duty on October 1, 1945. For his distinguished service during World War II, he was awarded two Legion of Merits.

7. Memberships and Affiliations

Richard E. Byrd was actively involved in a diverse array of organizations, reflecting his broad interests and commitment to various communities beyond his military and exploratory pursuits.

He was a prominent Freemason, raised as a Master Mason in Federal Lodge No. 1, Washington, D.C., on March 19, 1921. He later affiliated with Kane Lodge No. 454, New York City, on September 18, 1928, and was a member of National Sojourners Chapter No. 3 in Washington. In 1930, Kane Lodge honored him with a gold medal.

In 1931, Byrd became a compatriot of the Tennessee Society of the Sons of the American Revolution, assigned state membership number 605 and national membership number 50430. He received the society's War Service Medal for his contributions during World War I.

Byrd was also a member of numerous other patriotic, scientific, and charitable organizations, including the esteemed Explorers Club, the American Legion, and the renowned National Geographic Society. His role as Honorary National President of Pi Gamma Mu from 1931 to 1935 further highlighted his engagement with academic and social science communities.

8. Honors and Awards

Richard E. Byrd was one of the most highly decorated officers in the history of the United States Navy, receiving extensive recognition for his extraordinary achievements in exploration, aviation, and military service.

8.1. Military Decorations and Medals

By the time of his death, Byrd had accumulated 22 citations and special commendations, including nine for bravery and two for extraordinary heroism in saving lives. He is likely the only individual to have received the Medal of Honor, Navy Cross, Distinguished Flying Cross, and the Silver Lifesaving Medal. He was also one of the very few individuals to receive all three Antarctic expedition medals issued for expeditions prior to World War II.

Below is a summary of his military decorations and medals:

| Naval Aviator Badge (1917) | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1st Row | Medal of Honor (1926) | ||||||||

| 2nd Row | Navy Cross (1929) | Navy Distinguished Service Medal with award star (1926, 1941) | Legion of Merit with award star (1943, 1946) | ||||||

| 3rd Row | Distinguished Flying Cross (1927) | Navy Commendation Medal with two stars (1944) | Silver Lifesaving Medal (1914) | ||||||

| 4th Row | Byrd Antarctic Expedition Medal issued in Gold (1930) | Second Byrd Antarctic Expedition Medal (1937) | United States Antarctic Expedition Medal issued in Gold (1945) | ||||||

| 5th Row | Mexican Service Medal (1918) | World War I Victory Medal with commendation star and two campaign clasps (1919) | American Defense Service Medal with service star (1940) | ||||||

| 6th Row | European-African-Middle Eastern Campaign Medal with battle star (1943) | Asiatic-Pacific Campaign Medal with two battle stars (1942) | World War II Victory Medal (1945) | ||||||

| 7th Row | Antarctic Service Medal (1960, posthumous) | Commander of the Legion of Honor (1931, France) (Officer in 1927) | Order of Christopher Columbus (1945, Santo Domingo) | ||||||

| 8th Row | Commander of the Order of Aviz (1921, Portugal) | Officer, Order of Saints Maurice and Lazarus (circa 1930, Italy) | Officer, Order of Aeronautical Virtue (circa 1930, Romania) | ||||||

Byrd was posthumously eligible for the Antarctic Service Medal, established in 1960, for his participation in Operation Highjump (1946-1947) and Operation Deep Freeze (1955-1956). He also received numerous other awards from governmental and private entities in the United States.

- Dates of Rank**

| Ensign | Lieutenant, Junior Grade | Lieutenant |

|---|---|---|

|  |  |

| June 8, 1912 | June 8, 1915 (Retired on March 15, 1916.) | September 2, 1918 |

| Lieutenant Commander | Commander | Rear Admiral |

|---|---|---|

|  |  |

| September 21, 1918 (Temporary. Revoked on December 31, 1921.) February 10, 1925 (Permanent.) | December 21, 1926 By act of Congress. (Date of rank - May 9, 1926.) | December 21, 1929 By act of Congress. |

- Medal of Honor Citation**

Rank and organization: Commander, United States Navy. Born: October 25, 1888, Winchester, Virginia. Appointed from: Virginia.

Citation:

"For distinguishing himself conspicuously by courage and intrepidity at the risk of his life, in demonstrating that it is possible for aircraft to travel in continuous flight from a now inhabited portion of the earth over the North Pole and return."

Byrd, along with Machinist Floyd Bennett, was presented with the Medal of Honor by President Calvin Coolidge on March 5, 1927.

- Navy Cross Citation**

"The President of the United States of America takes pleasure in presenting the Navy Cross to Rear Admiral Richard Evelyn Byrd Jr. (NSN: 0-7918), United States Navy, for extraordinary heroism in the line of his profession as Commanding Officer of the Byrd Antarctic Expedition I, in that on November 28, 1929 he took off in his "Floyd Bennett" from the Expedition's base at Little America, Antarctica and, after a flight made under the most difficult conditions he reached the South Pole on November 29, 1929. After flying some distance beyond this point he returned to his base at Little America. This hazardous flight was made under extreme conditions of cold, over ranges and plateaus extending nine to ten thousand feet above sea level and beyond probable rescue of personnel had a forced landing occurred. Rear Admiral Richard E. Byrd, U.S.N, Retired, was in command of this flight, navigated the airplane, made the mandatory preparations for the flight, and through his untiring energy, superior leadership, and excellent judgment the flight was brought to a successful conclusion."

- First Distinguished Service Medal Citation**

"The President of the United States of America takes pleasure in presenting the Navy Distinguished Service Medal to Commander Richard Evelyn Byrd Jr. (NSN: 0-7918), United States Navy, for exceptionally meritorious and distinguished service in a position of great responsibility to the Government of the United States, in demonstrating, by his courage and professional ability that heavier-than-air craft could in continuous flight travel to the North Pole and return."

General Orders: Letter Dated August 6, 1926

- Second Distinguished Service Medal Citation**

"The President of the United States of America takes pleasure in presenting a Gold Star in lieu of a Second Award of the Navy Distinguished Service Medal to Rear Admiral Richard Evelyn Byrd Jr. (NSN: 0-7918), United States Navy, for exceptionally meritorious and distinguished service in a position of great responsibility to the Government of the United States as Commanding Officer of the U.S. Antarctic Service. Rear Admiral Byrd did much toward the difficult task of organizing the expedition, which was accomplished in one fourth of the time generally necessary for such undertakings. In spite of a short operating season, he established two Antarctic bases 1.50 K mile apart, where valuable scientific and economic investigations are now being carried on. With the USS Bear, he penetrated unknown and dangerous seas where important discoveries were made; in addition to which he made four noteworthy flights, resulting in the discovery of new mountain ranges, islands, more than 100.00 K mile2 of area, a peninsula and 700 mile of hitherto unknown stretches of the Antarctic coast. The operations of the Antarctic Service have been a credit to the Government of the United States. His qualities of leadership and unselfish devotion to duty are in accordance with the highest traditions of the United States Naval Service."

- First Legion of Merit Citation**

"The President of the United States of America takes pleasure in presenting the Legion of Merit to Rear Admiral Richard Evelyn Byrd Jr. (NSN: 0-7918), United States Navy, for exceptionally meritorious conduct in the performance of outstanding services to the Government of the United States while in command of a Special Navy Mission to the Pacific from August 27, 1943, to December 5, 1943, when thirty-three islands of the Pacific were surveyed or investigated for the purpose of recommending air base sites of value to the United States for its defense or for the development of post-war civil aviation. In this service Admiral Byrd exercised fine leadership in gaining the united effort of civilian, Army, and Navy experts. He displayed courage, initiative, vision, and a high order of ability in obtain data and in submitting reports which will be of great present and future value to the National Defense and to the Government of the United States in the post-war period."

Action Date: August 27 - December 5, 1943

- Second Legion of Merit Citation**

"The President of the United States of America takes pleasure in presenting a Gold Star in lieu of a Second Award of the Legion of Merit to Rear Admiral Richard Evelyn Byrd Jr. (NSN: 0-7918), United States Navy, for exceptionally meritorious conduct in the performance of outstanding services to the Government of the United States as Confidential Advisor to the Commander in Chief, United States Fleet and Chief of Naval Operations from March 26, 1942 to May 10, 1942, August 14, 1942 to August 26, 1943, and from December 6, 1943 to October 1, 1945. In the performance of his duty Rear Admiral Byrd served in the Navy Department and in various areas outside the continental limits of the United States, employed on special missions on the fighting fronts in Europe and the Pacific. In all assignments his thoroughness, attention to detail, keen discernment, professional judgment and zeal produced highly successful results. His wise counsel, sound advice and foresight in planning constituted a material contribution to the war effort and to the success of the United States Navy. The performance of duty of Rear Admiral Byrd was at all times in keeping with the highest traditions and reflected credit upon himself and the United States Naval Service."

General Orders: Board Serial 176P00 (February 4, 1946)

Action Date: March 26, 1942 - October 1, 1945

- Distinguished Flying Cross Citation**

"The President of the United States of America takes pleasure in presenting the Distinguished Flying Cross to Commander Richard Evelyn Byrd Jr. (NSN: 0-7918), United States Navy, for extraordinary achievement while participating in aerial flight; in recognition of his courage, resourcefulness and skill as Commander of the expedition which flew the airplane "America" from New York City to France from June 29 to July 1, 1927, across the Atlantic Ocean under extremely adverse weather conditions which made a landing in Paris impossible; and finally for his discernment and courage in directing his plane to a landing at Ver sur Mer, France, without serious injury to his personnel, after a flight of 39 hours and 56 minutes."

Action Date: June 29 - July 1, 1927

- Letter of Commendation**

"He rendered valuable service as Secretary and Organizer of the Navy Department Commission on Training Camps, and trained men in aviation in the ground school in Pensacola, and in charge of rescue parties and afterwards in charge of air forces in Canada."

Awarded for service from 1917 to 1918 during World War I.

8.2. Other Honors and Recognition

Admiral Byrd holds the unique distinction of being the only person to have three ticker-tape parades in New York City held in his honor (in 1926, 1927, and 1930). He was also one of only four American military officers in history permitted to wear a medal featuring his own image, the others being Admiral George Dewey, General John J. Pershing, and Admiral William T. Sampson. As Byrd's image appears on both the first and second Byrd Antarctic Expedition Medals, he was uniquely entitled to wear two medals depicting himself.

He was a recipient of the prestigious Langley Gold Medal, awarded by the Smithsonian Institution for outstanding achievements in aviation. Additionally, he was the seventh recipient of the Hubbard Medal, presented by the National Geographic Society for his flight to the North Pole, joining a distinguished list of honorees that includes Robert Peary, Roald Amundsen, and Charles Lindbergh.

Byrd received numerous medals from non-governmental organizations, recognizing his global impact. These included the David Livingstone Centenary Medal from the American Geographical Society, the Loczy Medal from the Hungarian Geographical Society, the Vega Medal from the Swedish Geographical Society, and the Elisha Kent Kane Medal from the Philadelphia Geographical Society.

In 1927, the Boy Scouts of America created a new category of "Honorary Scout" and bestowed this distinction upon Byrd. This honor was reserved for "American citizens whose achievements in outdoor activity, exploration, and worthwhile adventure are of such an exceptional character as to capture the imagination of boys." Also in 1927, the City of Richmond dedicated the Richard Evelyn Byrd Flying Field, now known as Richmond International Airport, in Henrico County, Virginia. Byrd's Fairchild FC-2W2, NX8006, Stars And Stripes, is on display at the Virginia Aviation Museum located on the north side of the airport, on loan from the National Air and Space Museum in Washington, D.C.

In 1929, he received the Silver Buffalo Award from the Boy Scouts of America. That same year, he was also awarded the Langley Gold Medal from the Smithsonian Institution. The Lunar crater Byrd is named after him, as is the United States Navy dry cargo ship USNS Richard E. Byrd (T-AKE-4) and the now decommissioned Charles F. Adams-class guided missile destroyer USS Richard E. Byrd (DDG-23).

In 1930, Byrd was elected to the American Philosophical Society. In Glen Rock, New Jersey, the Richard E. Byrd School was dedicated in 1931. On March 31, 1934, Admiral Byrd was awarded the CBS Medal for Distinguished Contribution to Radio during a regularly scheduled broadcast. His short-wave relay broadcasts from his second Antarctic expedition established a new chapter in communication history, making him the sixth individual to receive this award.

The Institute of Polar Studies at the Ohio State University officially changed its name to the Byrd Polar Research Center (BPRC) on January 21, 1987. This occurred after the center acquired Byrd's expeditionary records, personal papers, and other memorabilia in 1985 from the estate of Marie A. Byrd, the admiral's late wife. His papers formed the nucleus for the establishment of the BPRC Polar Archival Program in 1990. In 1958, the Richard Byrd library, part of the Fairfax County Public Library system, opened in Springfield, Virginia.

Richard E. Byrd Elementary School, a Department of Defense school located in Negishi (Yokohama, Japan), opened on September 20, 1948. Its name was changed to R.E. Byrd Elementary School on April 5, 1960. Memorials to Byrd can be found in two cities in New Zealand, Wellington and Dunedin, as New Zealand served as his departure point for several Antarctic expeditions.

The 50th anniversary of Byrd's first flight over the South Pole was commemorated in 1979 with a set of two postage stamps by the Australian Antarctic Territory, and a commemorative flag was designed. The long-range short-wave voice transmissions from Byrd's Antarctic expedition in 1934 were recognized as an IEEE Milestone in 2001. Admiral Richard E. Byrd Middle School, located in Frederick County, Virginia, opened in 2005 and is decorated with pictures and letters from Byrd's life and career. He was inducted into Phi Beta Kappa as an honorary member at the University of Virginia, and into the International Air and Space Hall of Fame at the San Diego Air and Space Museum in 1968. Richard E. Byrd Middle School in Sun Valley, California, is also named after him, opening in its current location in 2008 after its original site became Sun Valley High School.

9. Death

Admiral Richard E. Byrd died in his sleep from a heart ailment at the age of 68 on March 11, 1957. He passed away at his home at 7 Brimmer Street in the Beacon Hill neighborhood of Boston. He is interred at Arlington National Cemetery.

10. Legacy and Impact

Richard E. Byrd's enduring legacy is multifaceted, spanning polar exploration, aviation technology, and scientific understanding of Antarctica, firmly cementing his place in American history and popular culture. His expeditions, particularly to Antarctica, were pivotal in expanding geographical knowledge, mapping vast unknown territories, and establishing the first permanent U.S. presence on the continent. The scientific investigations conducted during his expeditions, covering geography, meteorology, resources, and oceanography, laid crucial groundwork for future research. His advocacy for ski-equipped aircraft and his meticulous logistical planning pushed the boundaries of aerial exploration in extreme environments.

Byrd's life also resonated in popular culture. Jacques Vallée in his book Confrontations mentions a "spurious story" about "'holes in the pole' allegedly found by Admiral Byrd," when he quotes Clint Chapin of the Copper Medic case as believing the UFOs came from inside the earth. This highlights how his explorations, particularly into uncharted territories, sparked public imagination and even gave rise to fringe theories. In Maggie Shipstead's novel Great Circle, Byrd and the Little America bases serve as the final stop in Marian Graves' ambitious journey to circumnavigate the globe by flight over both the North and South Poles, underscoring his symbolic role as an ultimate explorer. His famous quote, Khi sống không có mục đích, cuộc sống của con người tự tan rã rồi chấm dứtWhen living without purpose, human life disintegrates and endsVietnamese, reflects his philosophy of purposeful endeavor.