1. Early Life and Education

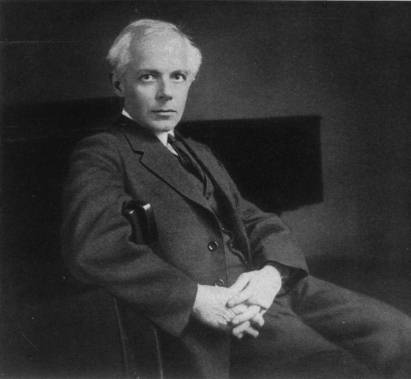

Joseph Szigeti's early life and education laid the foundation for his distinguished career, marked by a musically inclined family background and tutelage under a renowned Hungarian pedagogue.

1.1. Birth and Family Background

Joseph Szigeti was born Joseph "Jóska" Singer to a Jewish family in Budapest, Austria-Hungary, on September 5, 1892. His family was deeply musical; his father was a chief player in a cafe orchestra, and many of his uncles were musicians, including one who played the double bass. When Szigeti was three years old, his mother passed away, and he was subsequently sent to live with his grandparents in the small Carpathian town of Máramaros-Sziget (modern-day Sighetu Marmației, Romania), from which he later derived his surname, Szigeti. He grew up immersed in music, with the town band consisting almost entirely of his uncles.

1.2. Childhood and Early Training

Szigeti spent his early childhood in the Transylvanian town of Máramaros-Sziget, at the foothills of the Carpathian Mountains. He received informal lessons on the `cimbalomHungarian` from his aunt before beginning formal violin lessons with his Uncle Bernat at the age of six. He quickly demonstrated exceptional talent for the instrument. After initial guidance from his father, he received further instruction from a member of an opera orchestra at a private music school preparatory course in Budapest.

1.3. Study with Jenő Hubay

Recognizing his prodigious talent, Szigeti's father took him to Budapest for advanced training. After a brief period with an unsuitable teacher, Szigeti successfully auditioned for the Franz Liszt Academy of Music and was admitted directly into the class of the renowned violinist and pedagogue Jenő Hubay. Hubay, a former student of Joseph Joachim in Berlin, was by then considered one of Europe's foremost violin teachers and a key figure in the Hungarian violin tradition. Szigeti joined a distinguished group of students in Hubay's studio, including Franz von Vecsey, Emil Telmányi, Jelly d'Arányi, and Stefi Geyer.

1.4. Encounter with Joseph Joachim

Szigeti had an early encounter with the esteemed violinist Joseph Joachim. According to one account, at the age of 12 in 1904, Szigeti visited Joachim in Berlin and performed Ludwig van Beethoven's Violin Concerto, receiving praise from the master, who even accompanied him on the piano and wrote a positive prediction in his autograph book. Later, in 1906, his teacher Hubay again took Szigeti to play for Joachim in Berlin. Joachim was impressed and offered to take Szigeti as a student to complete his studies. However, Szigeti declined the offer, citing both his loyalty to Hubay and a perceived lack of rapport between Joachim and his students.

2. Career

Joseph Szigeti's career spanned decades, evolving from a child prodigy to an internationally renowned concert artist, educator, and advocate for new music.

2.1. Child Prodigy Debut

In the early 20th century, Europe saw a proliferation of child prodigies, a phenomenon that also extended to Hubay's studio, where Szigeti and his fellow `wunderkinderGerman` performed extensively in special recitals and salon concerts. After two years of study at the conservatory, Szigeti made his Berlin debut in 1905 at the age of thirteen. His formidable program included Johann Sebastian Bach's Chaconne in D minor, Heinrich Wilhelm Ernst's Concerto in F-sharp minor, and Niccolò Paganini's Witches Dance. The event garnered a mention in the Sunday supplement of the Berliner Tageblatt, captioned "A Musical Prodigy: Josef Szigeti." Following this, Szigeti spent several months with a summer theater company, performing mini-recitals between acts of folk operettas. The next year, in 1906, he performed at a circus in Frankfurt under the pseudonym "Jóska Szulagi." Also in 1906, he made his British debut at London's Bechstein Hall, now known as Wigmore Hall.

2.2. Mentorship by Ferruccio Busoni and Artistic Development

During a major concert tour of England, Szigeti met a music-loving couple in Surrey who effectively adopted him. He also toured with an all-star ensemble that included legendary singer Nellie Melba, pianists Ferruccio Busoni and Wilhelm Backhaus, flutist Philippe Gaubert, and singer John McCormack. The most pivotal encounter during this period was with Ferruccio Busoni, the renowned pianist and composer, who became Szigeti's mentor. Their friendship deepened and lasted until Busoni's death in 1924. Szigeti himself acknowledged that before meeting Busoni, his life as a young prodigy was marked by a certain laziness and indifference; he was accustomed to performing crowd-pleasing salon pieces and dazzling virtuosic encores without much intellectual engagement. Busoni profoundly influenced Szigeti's artistic development, particularly through their meticulous study of Bach's Chaconne, which, in Szigeti's words, "shook me once and for all out of my adolescent complacency." Busoni instilled in Szigeti a commitment to musical integrity, guiding him away from superficial virtuosity towards the demanding path of a true musician.

2.3. Illness and Recovery

In 1913, Szigeti was diagnosed with tuberculosis, which necessitated a stay in a sanatorium in Davos, Switzerland, and temporarily interrupted his burgeoning concert career. During his recovery, he re-established acquaintance with composer Béla Bartók, who was also recuperating from pneumonia. Their casual acquaintance from conservatory days blossomed into a deep friendship that endured until Bartók's death in 1945. Despite his illness, Szigeti's doctor recommended practicing the violin for 25 to 30 minutes daily. Szigeti was able to visit Bartók for the last time in 1943 at Mount Sinai Hospital (Manhattan) in New York, as Bartók's health worsened, reading Turkish poems together.

2.4. Professorship in Geneva

Having made a full recovery from tuberculosis, Szigeti was appointed Professor of Violin at the Geneva Conservatory of Music in 1917, at the age of 25. He held this position until 1924. While generally satisfying, Szigeti found the role often frustrating due to the varying quality of his students. Nevertheless, his years teaching in Geneva provided a valuable opportunity to deepen his understanding of music as an art form, encompassing aspects such as chamber music, orchestral performance, music theory, and composition. It was also in Geneva that he met Wanda Ostrowska, a young woman of Russian parentage who had been stranded in the city by the Russian Revolution of 1917. Szigeti and Ostrowska fell in love and married in 1919.

2.5. American Debut and International Concert Tours

In 1925, Szigeti's career took a significant turn when he met conductor Leopold Stokowski and performed Bach's Chaconne in D minor for him. Within two weeks, Szigeti received an invitation from Stokowski's manager in Philadelphia for his American debut with the Philadelphia Orchestra later that year. Having never performed with or even heard an American orchestra, Szigeti experienced considerable stage fright. He was also struck by the American concert scene, which he found heavily influenced by publicity and popularity-driven agents and managers. He believed these individuals preferred popular light salon pieces over the works of the great masters, a sentiment he famously illustrated by quoting an impresario who told him, regarding Ludwig van Beethoven's Kreutzer Sonata, "Well, let me tell you, Mister Dzigedy-and I know what I'm talking about-your Krewtzer Sonata bores the pants off my audiences!"

By 1930, Szigeti had firmly established himself as a major international concert violinist. He embarked on extensive concert tours across Europe, the United States, and Asia, forging connections with many of the era's leading instrumentalists, conductors, and composers. He made his first visit to Japan in 1931, followed by another in 1932.

2.6. Advocacy for New Music

Szigeti distinguished himself as a fervent advocate for new music, frequently incorporating new or lesser-known works into his recitals alongside established classics. Many contemporary composers dedicated new compositions to him, including Ernest Bloch's Violin Concerto, Béla Bartók's Rhapsody No. 1, and Eugène Ysaÿe's Solo Sonata No. 1. Other dedicatees included David Diamond and Hamilton Harty. Bloch notably delayed the premiere of his Violin Concerto for a full year to ensure Szigeti could be the soloist, stating that "Modern composers realize that when Szigeti plays their music, their inmost fancy, their slightest intentions become fully realized, and their music is not exploited for the glorification of the artist and his technique, but that artist and technique become the humble servant of the music." Ysaÿe's own inspiration to compose his Six Sonatas for Solo Violin stemmed from hearing Szigeti's performances of Johann Sebastian Bach's Six Sonatas and Partitas, intending his works as a modern counterpart.

Perhaps Szigeti's most significant musical partnership was with his close friend, Béla Bartók. Bartók dedicated his First Rhapsody for violin and orchestra (or piano) to Szigeti in 1928. In 1938, Szigeti and clarinetist Benny Goodman jointly commissioned a trio from Bartók, which evolved into the three-movement Contrasts for piano, violin, and clarinet. In 1944, with both Szigeti and Bartók having fled to the United States to escape the war, Bartók's health was failing, and he was in financial distress and depression. Szigeti came to his friend's aid by securing donations for Bartók's medical treatment and, along with conductor Fritz Reiner, persuaded Serge Koussevitzky to commission what became Bartók's highly acclaimed Concerto for Orchestra, which brought Bartók much-needed financial security and an emotional boost.

Beyond works dedicated to him, Szigeti actively championed the music of other contemporary composers. He was among the first violinists to integrate Sergei Prokofiev's First Violin Concerto into his standard repertoire, a piece which Prokofiev himself praised Szigeti for playing "wonderfully." Szigeti frequently performed and recorded works by Igor Stravinsky, including the Duo Concertante, recorded with the composer at the piano in 1945. He also recorded the Berg Violin Concerto twice, under the baton of Dimitri Mitropoulos, and made a premier recording of the Bloch concerto in 1939 with the Orchestre de la Société des Concerts du Conservatoire conducted by Charles Munch.

2.7. Recording Career

From the 1920s until his retirement in 1960, Szigeti maintained a prolific recording career, leaving behind a significant legacy of interpretations. His notable recordings include the historic Library of Congress sonata recital with Béla Bartók, and Bartók's Contrasts with Benny Goodman on clarinet and the composer at the piano. He recorded major violin concertos by Ludwig van Beethoven, Johannes Brahms, Felix Mendelssohn, Sergei Prokofiev (No. 1), and Ernest Bloch, collaborating with esteemed conductors such as Bruno Walter, Hamilton Harty, and Sir Thomas Beecham. His discography also features various works by Johann Sebastian Bach, Ferruccio Busoni, Arcangelo Corelli, George Frideric Handel, and Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart. One of his final recordings was of Bach's Six Sonatas and Partitas for solo violin; despite a noticeable deterioration in his technique by that time, this recording is highly valued for Szigeti's profound insight and interpretive depth. In 1944, Szigeti joined Jack Benny in a comic performance of František Drdla's Souvenir in the film Hollywood Canteen.

2.8. Later Years and Retirement

During the 1950s, Szigeti began to develop arthritis in his hands, which noticeably affected his playing technique. Despite this physical decline, his intellectual and musical expression remained powerful, and he continued to attract large audiences to his concerts. A notable incident occurred in Naples, Italy, in November 1956, shortly after the Soviet suppression of the Hungarian uprising; upon his entrance to the stage, the audience erupted in wild applause and shouts of `Viva l'Ungheria!Italian` ("Long live Hungary!"), delaying the concert for nearly fifteen minutes.

In 1960, Szigeti officially retired from performing and returned to Switzerland with his wife. There, he primarily dedicated himself to teaching, though he also regularly traveled to judge international violin competitions. Top-tier students from across Europe and the United States sought his instruction, including Arnold Steinhardt, who spent the summer of 1962 with Szigeti. Steinhardt later remarked that "Joseph Szigeti was a template for the musician I would like to become: inquisitive, innovative, sensitive, feeling, informed." His notable students included Franco Gulli, Yoshio Unno, Yoko Kubo, Masuko Ushioda, Teiko Maehashi, and Hirofumi Fukai.

Toward the end of his life, Szigeti suffered from frail health, enduring strict diets and several hospital stays, but his friends noted that this did not diminish his characteristic cheerfulness. He passed away in Lucerne, Switzerland, on February 19, 1973, at the age of 80. The New York Times published a front-page obituary that concluded with a 1966 quote from violinist Yehudi Menuhin: "We must be humbly grateful that the breed of cultured and chivalrous violin virtuosos, aristocrats as human beings and as musicians, has survived into our hostile age in the person of Joseph Szigeti."

3. Artistic Philosophy and Playing Style

Joseph Szigeti's artistic philosophy was characterized by an intellectual approach to music, prioritizing deep understanding and integrity over mere technical display. His playing style, while sometimes drawing mixed technical reviews, was widely praised for its profound musicality and expressive depth.

3.1. Intellectual Approach and Musical Integrity

Joseph Szigeti's artistic philosophy was rooted in a profound intellectual approach and an unwavering commitment to musical integrity, earning him the nickname "The Scholarly Virtuoso." Influenced significantly by Ferruccio Busoni, he rejected the superficial virtuosity common among child prodigies, instead advocating for a deep understanding and fidelity to the composer's intentions. He believed that a violinist's primary concern should be musical goals rather than merely choosing the easiest or most dazzlingly virtuosic way to execute a passage. Szigeti was particularly attentive to tone color, advising that "The player should cultivate a seismograph-like sensitivity to brusque changes of tone colour caused by fingerings based on expediency and comfort rather than the composer's manifest or probable intentions."

Critics and fellow musicians often noted his dedication to the music itself. Haruo Yamada observed that Szigeti "rejected superficial beauty, constantly sought deep musical understanding. [He] didn't shy away from 'dirty' sounds. Sometimes the violin would creak." Isao Uno commented that while Szigeti's technique might not pass modern competition standards, he believed Szigeti "consciously avoided fluent playing and sweet tones," and that his "severe sound conveyed spiritual depth beyond the violin's limits, imbued with nobility." Kei Yoshimura described his style as appealing to those who valued musical spirituality, noting his bowing that "creaked the strings as if refusing smooth gliding" and his sometimes "sweet spots" in fingering, yet resulting in a rare artistry where "sounds appeal to the heart, bypassing senses." Some commentators, like Kazuhiko Watanabe, have associated Szigeti's performance style with the early 20th-century artistic movement of "New Objectivity" (`Neue SachlichkeitGerman`), suggesting he transformed violin playing from mere acrobatic display or sweet sentimentality into something "fierce and severe" that "approached the core of the music."

3.2. Evaluation of Technique and Tone

While Joseph Szigeti's musical insights, intellect, and interpretive depth were almost universally praised, the purely technical aspects of his playing often received a more mixed reaction. Boris Schwarz, writing in the New Grove Dictionary of Music and Musicians, noted that Szigeti's "performing technique was not always flawless and his tone lacked sensuous beauty, although it acquired a spiritual quality in moments of inspiration." Schwarz further observed that Szigeti's "old-fashioned" bow hold, with the elbow close to the body, produced "much emphatic power, but not without extraneous sounds," yet concluded that "Minor reservations, however, were swept aside by the force of his musical personality." This assessment reflects the general consensus: while his musical insights, intellect, and interpretive depth were almost universally praised, the purely technical aspects of his playing sometimes drew mixed reactions, with his tone occasionally being described as uneven.

For instance, a 1926 review in The New York Times criticized a recital for being "stiff and dry in its observance of letter and its absence of spirit," noting "dryness of tone and angularity of phrase," and even "passages of poor intonation." In contrast, a review from the previous year in the same publication, following a performance of the Beethoven concerto, praised his "rather small but beautiful tone, elegance, finish," and a "quiet sincerity," concluding that Szigeti was a player who commanded "esteem and respect for his musicianship, for the genuineness of his interpretations, and his artistic style."

Fellow musicians also offered candid assessments. John Holt, after hearing Szigeti perform the Beethoven Violin Concerto in London in 1952, observed that Szigeti "struggled considerably in fast and complex passages" and that his playing was "rough and tense." Holt inferred that Szigeti, aware of his technical limits, was determined to convey the beloved music, even at the cost of occasional mistakes. The esteemed pedagogue Carl Flesch reportedly criticized Szigeti's technique, citing "understudied" passages, "outdated bowing," and the bow often being "too close to the bridge" during detaché, staccato, and spiccato, sometimes resulting in "squeaky sounds." Despite these technical observations, the overall consensus among many was that his profound musicality transcended any technical imperfections.

4. Writings

Joseph Szigeti was a significant author, contributing both memoirs that offered reflections on his life and career, and an influential treatise on violin performance.

4.1. Memoirs and Reflections

Joseph Szigeti made significant contributions as an author, most notably through his memoirs, With Strings Attached: Reminiscences and Reflections, published in 1947. The New York Times reviewed the book favorably, describing it as "constructed along utterly anarchistic lines, with each episode and anecdote left pretty much on its own." Despite this unconventional structure, the review asserted that the book "also has the flavor of life in it, and it is marked by an exhilarating revolt against the custom of arranging catastrophes and triumphs under neat chapter headings." This autobiographical work offers valuable insights into his life, career, and reflections on the music world.

4.2. Treatise on Violin Playing

In 1969, Szigeti published his influential treatise on violin playing, Szigeti on the Violin. This book delves into his perspectives on the contemporary state of violin performance, the challenges facing musicians in the modern era, and a detailed examination of his understanding of violin technique. A prominent theme in the first part of the book is the evolving nature of violinists' careers. Szigeti expressed dismay at the shift from recitals, which were once central to establishing an artist's reputation, to the increasing dominance of competitions. He believed that the fast-paced and intense preparation required for high-level competitions was "incompatible with the slow maturing either of the performing artist or of the repertoire," leading to performances that "lack the stamp of authenticity, the mark of a personal view evolved through trial and error." He was also skeptical of the recording industry's impact, suggesting that the allure of recording contracts led many young artists to record works prematurely, contributing to an artificial and immature artistic development.

Szigeti also offered a lengthy and detailed explanation of his approach to violin technique. He emphasized that violinists should prioritize musical goals over merely choosing the easiest or most virtuosic way to play a passage. He was particularly concerned with tone color, advising that performers cultivate a "seismograph-like sensitivity to brusque changes of tone colour caused by fingerings based on expediency and comfort rather than the composer's manifest or probable intentions." Other topics discussed include the most effective position for a violinist's left hand, the violin works of Béla Bartók, a cautionary list of common misprints and editorial inaccuracies in the standard repertoire, and, most notably, the vital importance of Johann Sebastian Bach's Six Sonatas and Partitas for any violinist's technical and artistic development. Additionally, Szigeti authored Beethoven's Violin Works: For Performers and Listeners and Violin Practice Notes: 200 Annotated Excerpts for Practice and Performance.

5. Personal Life

Joseph Szigeti's personal life was marked by his marriage and family relationships, his experiences with emigration and wartime challenges, and his eventual naturalization as an American citizen before returning to Switzerland in his later years.

5.1. Marriage and Family

In 1918, while teaching in Geneva, Szigeti met and fell in love with Wanda Ostrowska, a young woman of Russian parentage who had been stranded in the city by the Russian Revolution of 1917. Despite numerous bureaucratic obstacles posed by the turbulent political situation in Europe, including the impossibility of contacting Ostrowska's family for parental consent, the couple was granted a dispensation to marry by Consul General Baron de Montlong, and they wed in 1919. Their only child, daughter Irene, was born in 1920 and lived until 2005. Irene later married the Georgian-Russian pianist Nikita Magaloff (1912-1992) in 1940.

5.2. Emigration, Wartime Experiences, and Citizenship

The turbulent political climate of the early 20th century directly impacted Szigeti's personal life. In 1920, just before the birth of his daughter Irene, Szigeti found himself stranded in Berlin during the Kapp Putsch, unable to return to Geneva due to a general strike that paralyzed the city. He recalled the "interminable days" of anxiety, particularly the "impossibility of communicating by phone or wire with my wife."

In 1940, the outbreak of World War II compelled the Szigetis to emigrate from Europe to the United States, where they settled in California. Their daughter Irene, however, remained in Switzerland, having married Nikita Magaloff earlier that year. A year later, Béla Bartók also fled to America, and just two days after his arrival, he and Szigeti performed a sonata recital at the Library of Congress in Washington, D.C.. Szigeti's letters from California describe Wanda's delight in their new life, raising a garden, chickens, and rabbits, and enjoying their "own little world" with dogs, an aviary, and various produce and flowers.

Szigeti narrowly escaped a fatal plane crash in January 1942 that claimed the life of movie star Carole Lombard. En route to Los Angeles for a concert, Szigeti was forced to give up his seat on TWA Flight 3 at a refueling stop in Albuquerque, New Mexico, to accommodate 15 soldiers who had priority during wartime. The plane, off course at night and operating under wartime blackout conditions, crashed into a mountain cliff after taking off from an intermediate stop in Las Vegas, killing everyone on board.

In 1950, Szigeti faced further challenges when he was detained at Ellis Island for five days upon returning from a European concert tour. He was held under the McCarran Internal Security Act and was only released after an Immigration and Naturalization Service inquiry cleared him of unrevealed charges. At the time, The New York Times reported that Szigeti had been a "sponsor or patron" of committees or organizations deemed "subversive" by the U.S. government. Szigeti publicly stated that he had never belonged to any political organization but had given money or lent his name to "this cause or that" during the war. The following year, in 1951, he became a naturalized American citizen.

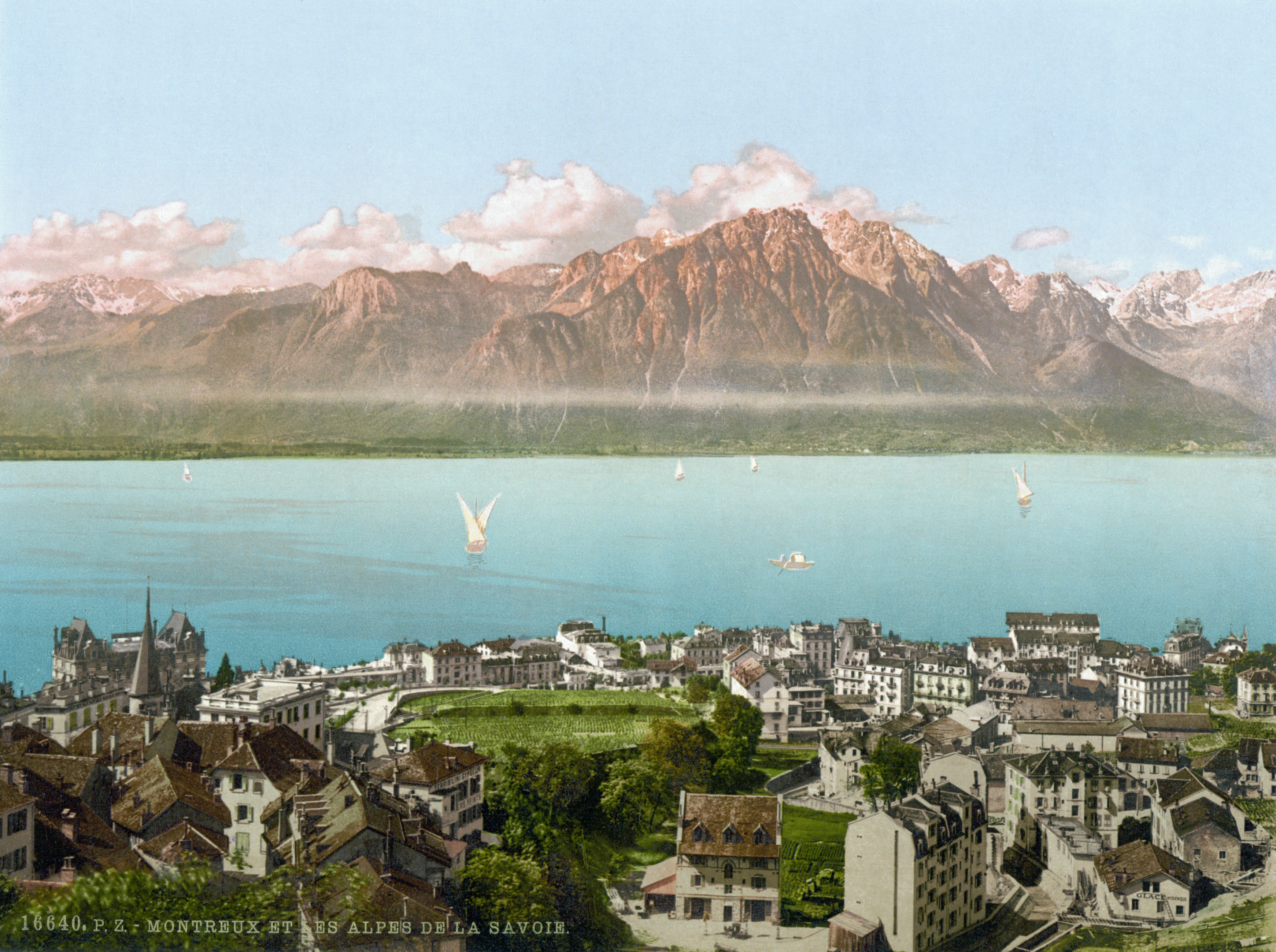

5.3. Later Life in Switzerland

In 1960, Szigeti and his wife returned to Europe, settling near Lake Geneva in Switzerland, close to the home of their daughter Irene and son-in-law Nikita Magaloff. They remained there for the rest of their lives. Wanda Szigeti passed away in 1971, two years before her husband. Joseph Szigeti found his final resting place beside his wife in the cemetery of Clarens, near Montreux. Their daughter Irene and son-in-law Nikita Magaloff are also buried just a few meters from their grave.

6. Reception

Joseph Szigeti's performances and artistry were met with varied critical assessments, though he consistently earned high esteem from his musical peers for his intellectual depth and character.

6.1. Critical Acclaim and Reservations

Joseph Szigeti's performances and artistry elicited a range of critical responses, though his intellectual depth and musical integrity were consistently lauded. Boris Schwarz, writing in the New Grove Dictionary of Music and Musicians, noted that Szigeti's "performing technique was not always flawless and his tone lacked sensuous beauty, although it acquired a spiritual quality in moments of inspiration." Schwarz further observed that Szigeti's "old-fashioned" bow hold, with the elbow close to the body, produced "much emphatic power, but not without extraneous sounds," yet concluded that "Minor reservations, however, were swept aside by the force of his musical personality." This assessment reflects the general consensus: while his musical insights, intellect, and interpretive depth were almost universally praised, the purely technical aspects of his playing sometimes drew mixed reactions, with his tone occasionally being described as uneven.

For instance, a 1926 review in The New York Times criticized a recital for being "stiff and dry in its observance of letter and its absence of spirit," noting "dryness of tone and angularity of phrase," and even "passages of poor intonation." In contrast, a review from the previous year in the same publication, following a performance of the Beethoven concerto, praised his "rather small but beautiful tone, elegance, finish," and a "quiet sincerity," concluding that Szigeti was a player who commanded "esteem and respect for his musicianship, for the genuineness of his interpretations, and his artistic style."

Among fellow musicians and critics, there were candid observations about his technique. John Holt, after hearing Szigeti perform the Beethoven Violin Concerto in London in 1952, noted Szigeti's visible struggles with fast and complex passages, describing his playing as "rough and tense." Holt inferred that Szigeti, aware of his technical limits, chose to prioritize conveying the beloved music, even at the risk of imperfections. The esteemed pedagogue Carl Flesch reportedly pointed out Szigeti's "understudied" passages, "outdated bowing," and the bow often being "too close to the bridge" during certain articulations, sometimes resulting in "squeaky sounds." Despite these technical observations, critics like Haruo Yamada highlighted Szigeti's rejection of superficial beauty in favor of profound musical understanding, even embracing "dirty sounds" and a "creaking" violin to achieve depth. Isao Uno suggested that Szigeti consciously avoided fluent playing and sweet tones, believing his "severe sound conveyed spiritual depth beyond the violin's limits, imbued with nobility." Kei Yoshimura characterized Szigeti as a "spiritual" musician whose unpolished yet deeply expressive style resonated profoundly with audiences. Kazuhiko Watanabe noted that Szigeti's style, sometimes associated with "New Objectivity" (`Neue SachlichkeitGerman`), transformed violin playing into a "fierce and severe" pursuit of music's core.

6.2. Admiration from Fellow Musicians

Among his fellow musicians, Joseph Szigeti commanded widespread admiration and respect. Violinist Nathan Milstein described him as an "incredibly cultured musician" whose "talent grew out of his culture," noting that Szigeti "was respected by musicians" and eventually gained the appreciation he deserved from the general public. Cellist János Starker hailed Szigeti as "one of the giants among the violinists I had heard from childhood on, and my admiration for him is undiminished up to this day." Starker recounted attending a late-career recital where, despite Szigeti's fingers having deteriorated due to arthritis, he still produced "heart-rending beauty."

Yehudi Menuhin extensively commented on Szigeti in his memoirs, acknowledging him as "the most cultivated violinist I have ever known" aside from George Enescu. Menuhin observed Szigeti's intense intellectual approach, stating that "two hours concentration wouldn't get them beyond the first three bars of a sonata-so much analysis and ratiocination went into his practice." While Menuhin found Szigeti's adjudication style somewhat "perverse" due to his focus on minute details, he nevertheless affirmed his deep admiration and fondness for Szigeti as both a violinist and a man. In 1945, Szigeti was introduced to the young pianist Georg Solti by his son-in-law Nikita Magaloff. Szigeti was impressed by Solti's skill after they played sonatas by Beethoven and Brahms, and invited him to move to the United States. However, Solti declined, concerned that such a move might impede his burgeoning career as a conductor.

7. Legacy and Influence

Joseph Szigeti's lasting impact on classical music is evident in his significant contributions to the violin repertoire and his profound influence on subsequent generations of musicians, establishing him as an artist of unwavering integrity.

7.1. Contribution to Violin Repertoire

Joseph Szigeti's legacy is profoundly marked by his significant contributions to the violin repertoire. He was an avid champion of new music, consistently integrating contemporary or lesser-known works into his concert programs alongside established classics. Many prominent composers wrote new works specifically for him, including Ernest Bloch's Violin Concerto, Béla Bartók's First Rhapsody and Contrasts, and Eugène Ysaÿe's Solo Sonata No. 1. Other dedicatees included David Diamond and Hamilton Harty. Bloch famously stated that Szigeti's performances ensured the composer's "inmost fancy, their slightest intentions become fully realized," with "artist and technique become the humble servant of the music." Ysaÿe's own set of solo sonatas were directly inspired by Szigeti's interpretations of Johann Sebastian Bach's solo works.

His partnership with Bartók was particularly fruitful, leading to the creation of several pivotal works. Beyond these dedications, Szigeti actively championed other contemporary composers, notably integrating Sergei Prokofiev's First Violin Concerto into the standard repertoire and frequently performing and recording works by Igor Stravinsky, including the Duo Concertante recorded with the composer at the piano. He also notably recorded the Berg Violin Concerto twice and made the premier recording of the Bloch concerto. Furthermore, Szigeti played a crucial role in establishing Bach's Six Sonatas and Partitas as standard concert repertoire, emphasizing their vital importance for any violinist's technical and artistic development.

7.2. Impact on Violin Pedagogy and Future Generations

Joseph Szigeti's influence extended significantly into violin pedagogy and the shaping of future generations of musicians. Following his retirement from the concert stage, he dedicated himself primarily to teaching, attracting top-class students from across Europe and the United States. He also frequently served as a judge for international violin competitions. His student Arnold Steinhardt encapsulated Szigeti's impact, describing him as "a template for the musician I would like to become: inquisitive, innovative, sensitive, feeling, informed."

Szigeti's pedagogical philosophy was further articulated in his writings, particularly his treatise Szigeti on the Violin. In this work, he shared his views on violin technique, the challenges facing musicians in the modern world, and the importance of a deep musical understanding over mere technical display. He was critical of the rising prominence of competitions and the recording industry, believing they often fostered an "artificially fast development" in young artists, leading to performances that "lack the stamp of authenticity." His emphasis on musical integrity, fidelity to the composer's intentions, and the profound study of works like Bach's solo sonatas and partitas served as a powerful model for thoughtful musicianship, inspiring countless violinists to pursue a more intellectual and artistically profound approach to their craft.

8. Death

Joseph Szigeti passed away in Lucerne, Switzerland, on February 19, 1973, at the age of 80. His death was marked by a front-page obituary in The New York Times, which included a tribute from violinist Yehudi Menuhin. Szigeti was laid to rest in the cemetery of Clarens, near Montreux, beside his wife Wanda, who had predeceased him in 1971. Their daughter Irene and son-in-law Nikita Magaloff are also buried just a few meters from their grave, reflecting the close family ties that endured through his life.