1. Overview

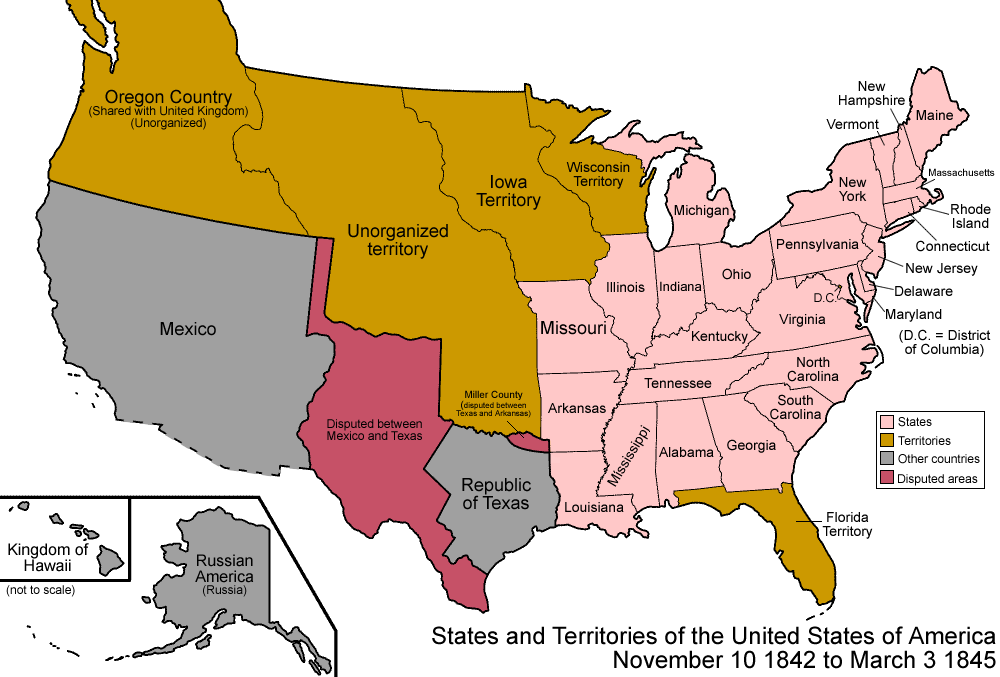

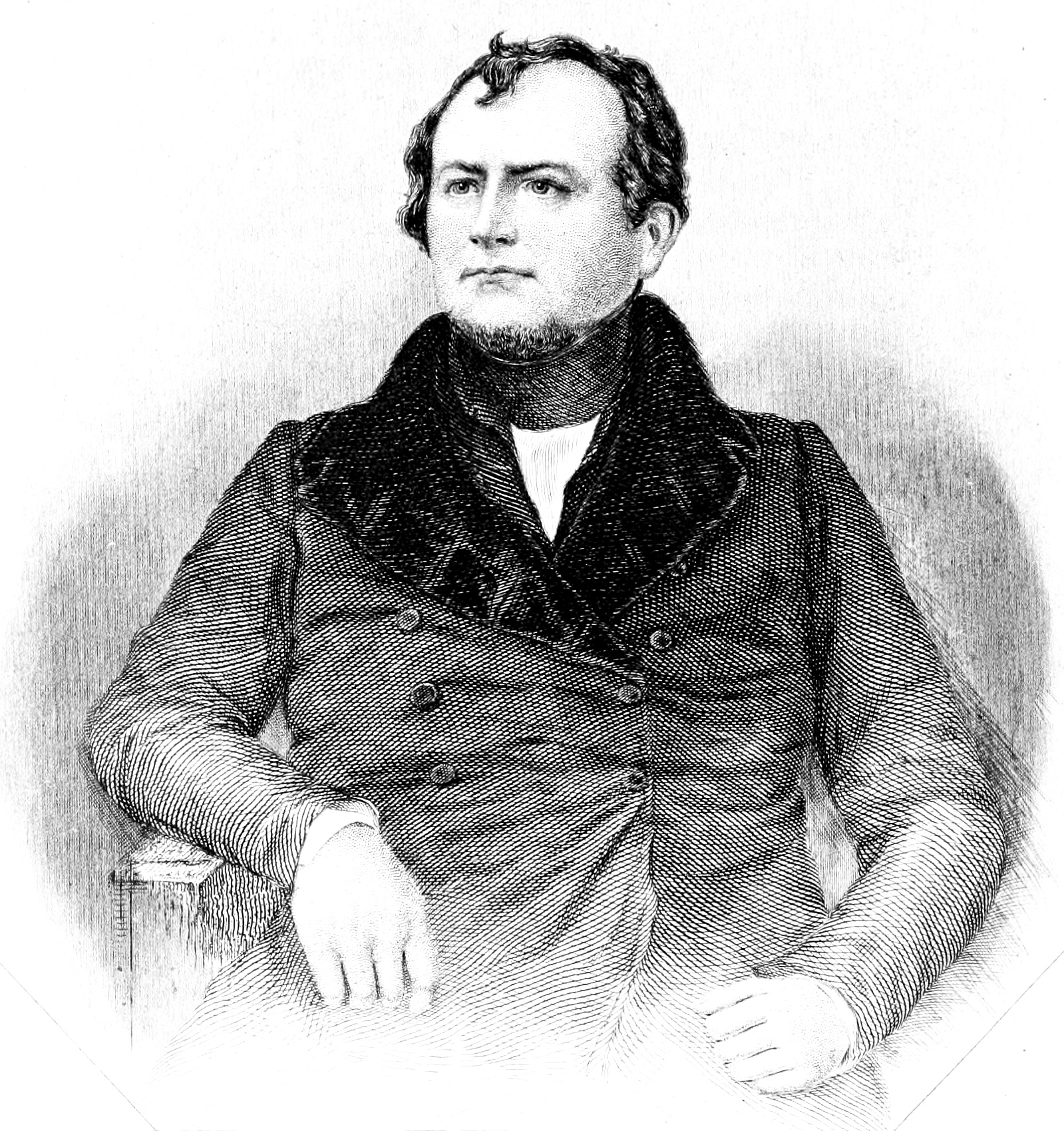

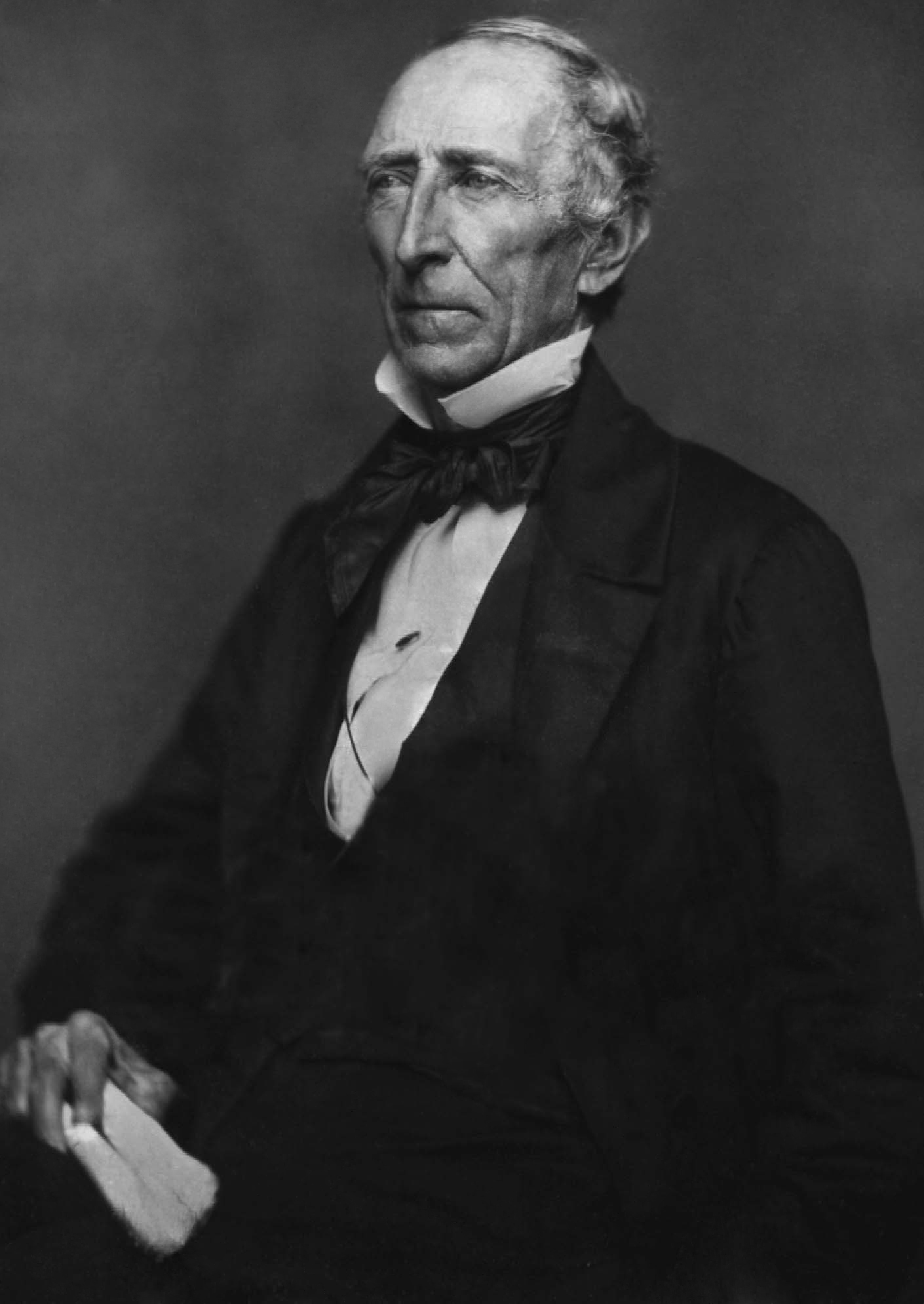

John Tyler, the tenth President of the United States, served from 1841 to 1845, after a brief tenure as the tenth Vice President of the United States in 1841. He was the second president born after the signing of the Declaration of Independence and the first vice president to ascend to the presidency due to the death of an incumbent. His presidency was marked by unprecedented circumstances and profound political conflict, setting crucial precedents for presidential succession while simultaneously highlighting the deep divisions within American politics, particularly concerning states' rights and slavery. Tyler's unexpected ascent to the presidency following the death of William Henry Harrison just 31 days into his term challenged the established political order and led to his estrangement from both major parties of the era, making him one of only two U.S. presidents to serve without a party affiliation (the other being Andrew Johnson).

Born into a prominent slaveholding Virginia family, Tyler was a staunch advocate of states' rights and a strict constructionist of the United States Constitution. His political career saw him serve as a Virginia state legislator and governor, a U.S. Representative, and a U.S. Senator. Initially a Democrat, he broke with President Andrew Jackson over issues of executive power and states' rights, aligning temporarily with the Whig Party. As president, Tyler frequently clashed with the Whig-controlled Congress, vetoing key legislation, which led to the mass resignation of his cabinet and his expulsion from the party, earning him the moniker "His Accidency." His administration, often described as controversial and beleaguered, nevertheless achieved significant foreign policy successes, including the Webster-Ashburton Treaty and the Treaty of Wanghia. His most defining policy goal was the annexation of the Republic of Texas, a move driven by his expansionist beliefs but deeply intertwined with the contentious issue of slavery, which further exacerbated national tensions and contributed to the eventual American Civil War.

Tyler's post-presidency was defined by his support for the Confederacy during the Civil War, a decision that has significantly shaped his historical reputation. While some scholars acknowledge his principled stand against party dictates and his foreign policy achievements, historians generally rank his presidency low, often criticizing his political isolation and his ultimate alignment with the forces of secession, which undermined national unity and democratic principles. His allegiance to the Confederacy led to his death not being officially recognized in Washington, D.C., and he remains the only U.S. president ever laid to rest under a flag not of the United States. Some views even consider him the only former president to be accused of treason.

2. Early Life and Education

John Tyler was born on March 29, 1790, at Greenway Plantation in Charles City County, Virginia, into a prominent slave-owning family with deep roots among the First Families of Virginia. His father, John Tyler Sr., known as Judge Tyler, was a close friend and college roommate of Thomas Jefferson. The elder Tyler served as Speaker of the Virginia House of Delegates, a state court judge, and later Governor of Virginia (1809-1811), and a judge on the U.S. District Court for the Eastern District of Virginia. He owned over 1,000 acres of tobacco fields and dozens of enslaved persons, and was a staunch supporter of states' rights. His mother, Mary Marot Armistead, died of a stroke in 1797 when John was seven years old. Tyler was of English descent, with his great-great-great-grandfather, Henry Tyler (circa 1604-1672), having emigrated from Shropshire, England, in 1653 to settle near Williamsburg, Virginia. Tyler himself claimed descent from Wat Tyler (died 1381), the leader of the Peasants' Revolt, though no genealogical evidence supports this claim.

Reared on the 1.2 K acre (1.20 K acre) Greenway Plantation, which included a six-room manor house, John and his seven siblings received an upper-class education. The plantation relied on enslaved labor to cultivate various crops, including wheat, corn, and tobacco. Judge Tyler employed tutors who academically challenged his children. John was known for his frail health, being thin and prone to diarrhea. At the age of 12, he continued a family tradition by entering the preparatory branch of the College of William & Mary, graduating from its collegiate branch in 1807 at age 17. During his studies, he developed a lifelong love for William Shakespeare and was influenced by Adam Smith's The Wealth of Nations, which shaped his economic views. Bishop James Madison, the college's president, served as a mentor to Tyler.

After graduation, Tyler studied law with his father, then a state judge, and later with Edmund Randolph, a former United States Attorney General. He was admitted to the Virginia bar at the age of 19, an age typically too young, but the admitting judge overlooked this detail. He began his legal practice in Richmond, the state capital. In 1813, the year of his father's death, Tyler purchased Woodburn Plantation, where he resided until 1821. By 1820, he owned 24 enslaved persons at Woodburn, having inherited 13 from his father.

3. Early Political Career

Tyler's political career began at a young age, marked by a strong adherence to states' rights and a cautious approach to federal power. His early service in Virginia state politics and a brief military stint during the War of 1812 laid the groundwork for his future federal roles.

3.1. Virginia State Politics

In 1811, at the age of 21, Tyler was elected to represent Charles City County in the Virginia House of Delegates, serving five consecutive one-year terms. During his time as a state legislator, he sat on the Courts and Justice Committee. From the outset, he displayed his defining political positions: staunch support for states' rights and strong opposition to a national bank. He notably joined Benjamin W. Leigh in supporting the censure of U.S. Senators William Branch Giles and Richard Brent for disregarding the Virginia legislature's instructions regarding the recharter of the First Bank of the United States.

After two years of private law practice, Tyler, feeling restless, successfully sought election to the House of Delegates again in 1823. He was easily elected, finishing first among three candidates. During this second tenure, he played a crucial role in saving the College of William & Mary from potential closure due to declining enrollment by proposing administrative and financial reforms, which proved successful.

In December 1825, Tyler was nominated and elected Governor of Virginia by the legislature, serving until March 1827. The office of governor under the original Virginia Constitution (1776-1830) was largely ceremonial, lacking even veto authority. Despite this, Tyler used the prominent platform to advocate for states' rights and oppose federal power concentration. He suggested that Virginia actively expand its road system to counter federal infrastructure proposals. His most visible act as governor was delivering a well-received eulogy for former President Thomas Jefferson, who died on July 4, 1826. He was unanimously reelected for a second one-year term in December 1826.

In 1829, Tyler was elected as a delegate to the Virginia Constitutional Convention of 1829-1830. Although a slaveowner from eastern Virginia who supported the existing system, he focused on promoting compromise and unity during the convention. His state-level service also included being president of the Virginia Colonization Society and later rector and chancellor of the College of William & Mary.

3.2. War of 1812 Service

Reflecting the prevailing anti-British sentiment in the South, Tyler urged support for military action at the onset of the War of 1812. After the British captured Hampton, Virginia, in the summer of 1813, Tyler enthusiastically organized a militia company, the Charles City Rifles, to defend Richmond. He commanded this company with the rank of captain. However, no attack on Richmond materialized, and he dissolved the company two months later, due to the perceived inactivity of his company. For his brief military service, Tyler received a land grant near what would later become Sioux City, Iowa. His father's death in 1813 led to Tyler inheriting 13 enslaved persons along with his father's plantation. In 1816, he resigned his legislative seat to serve on the Governor's Council of State, a group of eight advisors elected by the General Assembly.

4. Service in U.S. Congress

Tyler's progression into federal legislative roles saw him navigate the complex political landscape of the Era of Good Feelings and the rise of the Second Party System, further solidifying his commitment to strict constructionism and states' rights.

4.1. U.S. House of Representatives

In September 1816, the death of U.S. Representative John Clopton created a vacancy in Virginia's 23rd congressional district. Tyler successfully sought the seat, winning a narrow election and being sworn into the Fourteenth Congress on December 17, 1816, as a Democratic-Republican.

During his tenure in the U.S. House, Tyler remained a steadfast strict constructionist, opposing proposals for federal funding of internal improvements like ports and roadways, believing such projects were the responsibility of individual states. He opposed the American System, an economic plan proposed by Henry Clay that sought to increase federal funding for infrastructure and impose high tariffs to protect American manufacturers. He participated in an audit of the Second Bank of the United States in 1818, expressing dismay at perceived corruption and advocating for the revocation of its charter, though Congress rejected this. His first notable clash with General Andrew Jackson occurred after Jackson's 1818 invasion of Florida during the First Seminole War, with Tyler condemning Jackson for the execution of two British subjects, despite praising his character.

A major issue during the Sixteenth Congress (1819-1821) was the admission of Missouri to the Union and the question of slavery's legality within the new state. While acknowledging the ills of slavery, Tyler hoped that allowing its expansion westward would dilute the enslaved population in the East, potentially facilitating eventual abolition in states like Virginia through individual state action. He firmly believed Congress lacked the power to regulate slavery and that admitting states based on their slave or free status would lead to sectional conflict. Consequently, he did not support the Missouri Compromise, which admitted Missouri as a slave state and Maine as a free one, and prohibited slavery in northern territories. Throughout his time in Congress, he consistently voted against bills that would restrict slavery in the territories.

Citing frequent ill health and dissatisfaction with the largely symbolic nature of his dissenting votes, Tyler declined to seek renomination in late 1820. He also noted the financial difficulty of funding his children's education on a congressman's salary. He left office on March 3, 1821, returning to private law practice.

4.2. U.S. Senate

In January 1827, the Virginia General Assembly elected Tyler to the U.S. Senate, replacing the contentious John Randolph. Tyler, initially reluctant, accepted the nomination and resigned his governorship on March 4, 1827, as his Senate term began.

By the time of his senatorial election, the 1828 presidential campaign was underway, with John Quincy Adams challenged by Andrew Jackson. Though disliking both candidates' willingness to expand federal power, Tyler leaned towards Jackson, hoping he would limit federal spending on internal improvements. In the Twentieth Congress, Tyler served alongside his Virginia colleague Littleton Waller Tazewell, sharing strict constructionist views. He vigorously opposed national infrastructure bills and unsuccessfully resisted the protectionist Tariff of 1828, which critics called the "Tariff of Abominations." He remained a strong proponent of states' rights, asserting that states could "strike the Federal Government out of existence by a word."

Tyler soon found himself at odds with President Jackson, criticizing his emerging spoils system as an "electioneering weapon." He voted against many of Jackson's nominations, viewing them as unconstitutional or driven by patronage, an act considered "insurgency" within his party. He particularly objected to Jackson's use of recess appointments for treaty commissioners. However, Tyler did defend Jackson's Maysville Road veto and voted to confirm some of his appointments, including Martin Van Buren as Minister to Britain. In the 1832 presidential election, both Tyler and Jackson opposed the recharter of the Second Bank of the United States. Tyler voted to sustain Jackson's veto of the bank recharter bill and endorsed Jackson's successful reelection bid.

Tyler's relationship with the Democratic Party reached a breaking point during the nullification crisis of 1832-1833. While sympathetic to South Carolina's reasons for nullification, he rejected Jackson's use of military force against a state. He delivered a speech in February 1833 outlining his views and supported Henry Clay's Compromise Tariff of 1833 to gradually reduce tariffs. His vote against the Force Bill permanently alienated the pro-Jackson faction of the Virginia legislature. Despite this, with Clay's endorsement, Tyler was reelected to the Senate in February 1833 by a narrow margin.

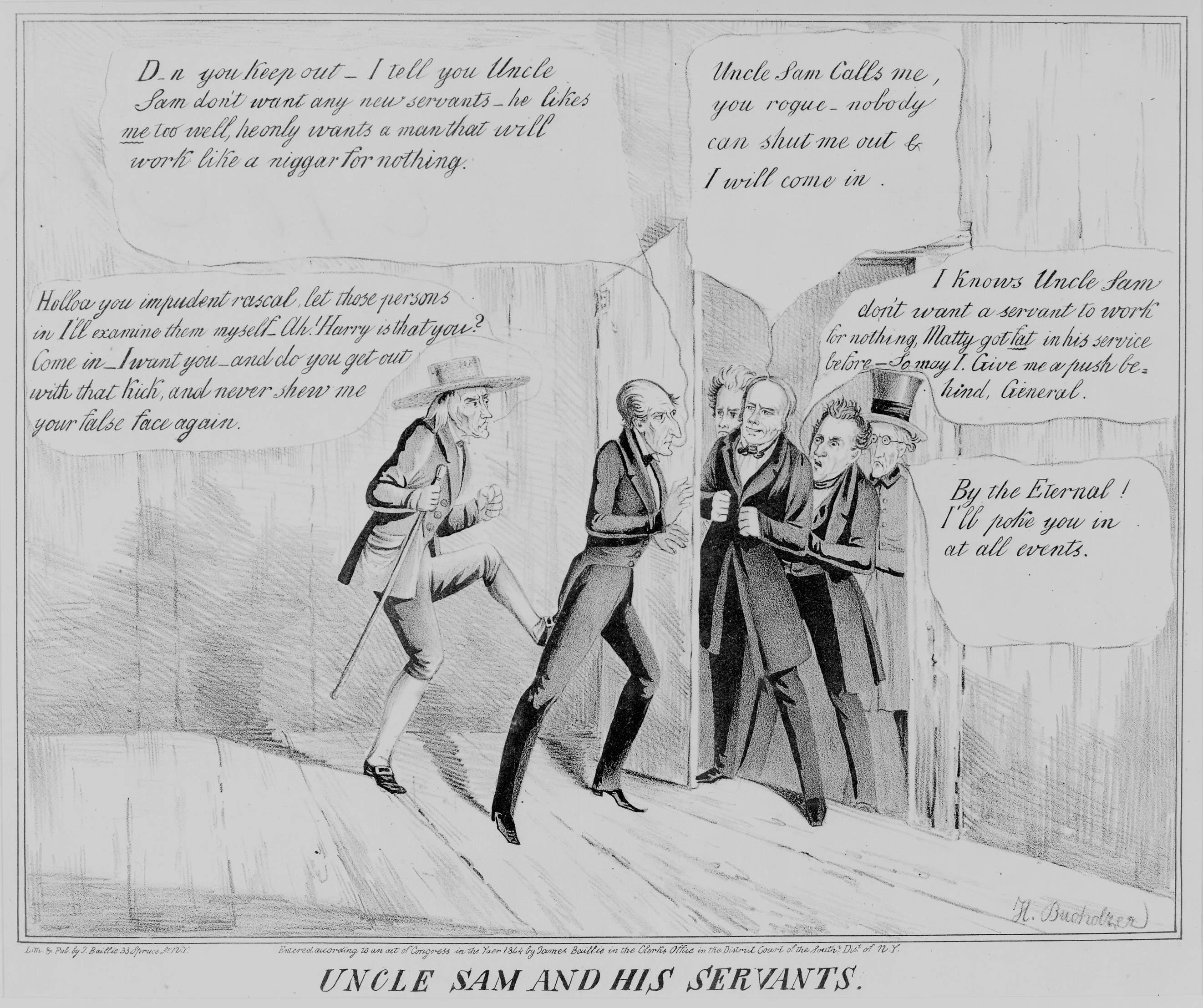

Jackson further alienated Tyler by moving to dissolve the Bank of the United States through executive order, which Tyler viewed as a "flagrant assumption of power" and a threat to the economy. In March 1834, Tyler joined Jackson's opponents, voting for two censure resolutions against the president. By this time, Tyler had affiliated with Clay's newly formed Whig Party, which controlled the Senate. On March 3, 1835, the Whigs symbolically elected Tyler President pro tempore of the Senate, making him the only U.S. president to have held this office.

When the Democrats gained control of the Virginia House of Delegates, Tyler was instructed to vote for a bill expunging Jackson's censure. Recognizing this would violate his principles, Tyler resigned his Senate seat on February 29, 1836, stating he would "set an example to my children which shall teach them to regard as nothing place and office, when either is to be attained or held at the sacrifice of honor." His successor in the Senate, William Cabell Rives, was a conservative Democrat. In February 1839, the General Assembly considered who should fill the expiring seat. Despite Tyler's expectation of Whig support, many Whigs found Rives a more politically expedient choice, hoping to ally with the conservative wing of the Democratic Party in the 1840 presidential election. This led to the Senate seat remaining vacant for almost two years until January 1841.

5. 1836 and 1840 Presidential Elections

Tyler's participation in the 1836 and 1840 presidential elections highlights the Whig Party's strategic attempts to build a broad coalition against the Democrats, often by selecting candidates who could appeal to diverse regional interests.

5.1. Vice Presidential Candidacies

Although Tyler intended to return to private life after his Senate resignation, he was soon drawn into the 1836 United States presidential election. He had been considered a vice presidential candidate since early 1835, and the Virginia Whigs nominated him the same day the Virginia Democrats issued the expunging instruction. The nascent Whig Party, not yet organized enough for a national convention, fielded multiple regional tickets against Martin Van Buren, Jackson's chosen successor. Tyler was part of the "states' rights" ticket in the middle and lower South, running with Hugh Lawson White. In Maryland, he ran with William Henry Harrison, and in South Carolina with Willie P. Mangum. The Whigs aimed to deny Van Buren an Electoral College majority, forcing the election into the House of Representatives. Tyler hoped to be one of the top two vice-presidential vote-getters, allowing the Senate to choose him under the Twelfth Amendment. Following the custom of the time, Tyler remained at home and did not campaign. He received only 47 electoral votes from Georgia, South Carolina, and Tennessee, and Harrison lost to Van Buren. The vice-presidential election was ultimately decided by the Senate, which selected Richard Mentor Johnson.

In the lead-up to the 1840 United States presidential election, the nation was grappling with a severe recession following the Panic of 1837. Van Buren's handling of the crisis had eroded public support, and with the Democratic Party fractured, the Whig presidential nominee was seen as likely to win. The 1839 Whig National Convention in Harrisburg, Pennsylvania, saw a deadlock between Harrison, Clay, and General Winfield Scott. Tyler attended the convention without official status. Despite initial bitterness over the unresolved Senate election, the influential Virginia delegation eventually backed Harrison for president.

The vice presidential nomination was largely considered secondary, as no president had ever failed to complete his elected term. Tyler's selection was strategic: as a Southern slaveowner, he balanced the ticket with Harrison, a Northerner, and allayed Southern fears about Harrison's potential abolitionist leanings. His previous vice-presidential candidacy in 1836 also made him a known figure. While some later claimed he was chosen out of a lack of other willing candidates, his biographer Robert Seager II concluded that Tyler was "put on the ticket to draw the South to Harrison. No more, no less."

The Whigs ran without a formal party platform, focusing instead on blaming Van Buren for the recession. The campaign was characterized by mass mobilization, including women, and public enthusiasm, with torchlight processions and rallies. The "Tippecanoe and Tyler Too" slogan, referring to Harrison's victory at the Battle of Tippecanoe, became famous. The "log cabin campaign" image, despite Harrison and Tyler's affluent backgrounds, was embraced to portray them as common men. Harrison and Tyler won by a significant electoral margin of 234-60, securing 53% of the popular vote, and the Whigs gained control of both houses of Congress.

6. Vice Presidency (1841)

As vice president-elect, Tyler remained at his Williamsburg home, expressing hopes that Harrison would be decisive in his new administration. He did not participate in cabinet selections or recommend anyone for federal office. Harrison, however, sought Tyler's advice on dismissing Van Buren appointees, with Tyler consistently recommending against removal. The two men met briefly in Richmond, but did not discuss politics.

Tyler was sworn in on March 4, 1841, in the Senate chamber, delivering a brief speech on states' rights before presiding over the confirmation of Harrison's cabinet. Expecting few responsibilities, he returned to Williamsburg. Historian Robert Seager II noted that had Harrison lived, Tyler "would undoubtedly have been as obscure as any vice-president in American history."

Harrison, however, struggled with the demands of office and the pressures from figures like Henry Clay. His health, a known concern during the campaign, deteriorated. After being caught in a rainstorm in late March, he developed pneumonia and pleurisy. Secretary of State Daniel Webster informed Tyler of Harrison's illness on April 1. On April 5, Fletcher Webster, chief clerk of the State Department, arrived at Tyler's home to officially inform him of Harrison's death the previous morning. Tyler immediately departed for Washington, arriving at dawn the next day.

7. Presidency (1841-1845)

John Tyler's presidency was a period of intense political struggle and significant foreign policy achievements, shaped by his unique accession to power and his unyielding commitment to his constitutional principles.

7.1. Accession to the Presidency

Harrison's death in office was an unprecedented event that created considerable uncertainty regarding presidential succession. Article II, Section 1, Clause 6 of the Constitution stated that in case of the President's removal, death, resignation, or inability, "the Same shall devolve on the Vice President." This led to a critical question: did the actual office of president devolve upon Tyler, or merely its powers and duties?

Within an hour of Harrison's death, the Cabinet met and, according to some accounts, determined that Tyler would be "vice-president acting president." However, Tyler firmly and decisively asserted that the Constitution granted him the full and unqualified powers of the office. He immediately took the presidential oath of office, administered by Judge William Cranch in his hotel room (Tyler considered it redundant but wanted to quell any doubt), moved into the White House, and assumed full presidential powers. This set a critical and lasting precedent for an orderly transfer of power following a president's death, a precedent that was later codified by the 25th Amendment in 1967. At 51, Tyler became the youngest president to date, though this record was surpassed by his immediate successor, James K. Polk, who was inaugurated at 49. As Harrison served only one month, Tyler became the longest-serving president who had not been elected to the office.

Tyler chose to retain Harrison's entire cabinet, despite several members being openly hostile to him. At his first cabinet meeting, Secretary Webster informed him of Harrison's alleged practice of making policy by majority vote within the cabinet. Tyler, astounded, immediately corrected them, asserting his sole responsibility for his administration and stating that resignations would be accepted if co-operation ceased.

Tyler delivered an informal inaugural address to Congress on April 9, reaffirming his belief in Jeffersonian democracy and limited federal power. His claim to the full presidency was not immediately accepted by opponents like John Quincy Adams, who argued he should be an "acting president." Henry Clay, who had intended to be "the real power behind a fumbling throne" under Harrison, viewed Tyler's presidency as a mere "regency." However, Congress ratified Tyler's decision through customary notification, and on May 31, 1841, the House passed a joint resolution confirming him as "President of the United States." The Senate followed suit on June 1, with even Clay and John C. Calhoun voting with the majority to reject amendments that would diminish Tyler's title. Despite this, Tyler's opponents often mocked him with nicknames like "His Accidency," and he would return unopened any correspondence addressed to the "vice president" or "acting president."

Tyler was seen as a strong leader for his decisive action in assuming the presidency. However, he generally held a limited view of presidential power, believing legislation should originate in Congress and the presidential veto should be reserved for unconstitutional laws or those against the national interest.

7.2. Conflict with the Whig Party

Tyler's presidency was dominated by severe political conflicts with the Whig Party, which had brought him to power. The Whigs, having gained control of Congress, expected Tyler to adhere to their legislative agenda and defer to their leader, Henry Clay. They particularly sought to curb the presidential veto power, a reaction to Andrew Jackson's perceived authoritarian use of it. Clay envisioned a parliamentary-style system where he would lead Congress, and initially, Tyler concurred with some Whig bills, signing the Preemption Act of 1841, a Distribution Act, a new bankruptcy law, and the repeal of the Independent Treasury.

However, the core issue of a national bank quickly put Tyler at odds with Congressional Whigs. Tyler, a strict constructionist, twice vetoed Clay's legislation for a national banking act. The second bill, though initially modified to address his objections, did not satisfy him in its final version. This practice, designed by Whigs to prevent Tyler from becoming a successful rival for the 1844 presidential nomination, became known as "heading Captain Tyler." Tyler proposed an alternative fiscal plan, the "Exchequer," but Clay's allies in Congress rejected it.

On September 11, 1841, following the second bank veto, almost all of Tyler's cabinet members, orchestrated by Clay, resigned one by one in an attempt to force Tyler's resignation and elevate Senate President pro tempore Samuel L. Southard to the White House. The sole exception was Secretary of State Daniel Webster, who remained to finalize the 1842 Webster-Ashburton Treaty and demonstrate his independence from Clay. Upon learning of Webster's decision to stay, Tyler reportedly declared, "Give me your hand on that, and now I will say to you that Henry Clay is a doomed man." On September 13, the Whigs in Congress formally expelled Tyler from the party. He faced severe criticism from Whig newspapers and received hundreds of assassination threats. The Whigs' animosity was so intense that they even refused to allocate funds for White House repairs, which had fallen into disrepair. Tyler became known as "the man without a party."

7.3. Economic and Fiscal Policies

Tyler's administration grappled with a significant economic crisis stemming from the Panic of 1837, which had plunged the nation into a depression. This crisis deeply divided the country over the best response.

By mid-1841, the federal government faced an projected budget deficit of 11.00 M USD. Tyler recognized the need for higher tariffs but aimed to keep them within the 20% rate established by the Compromise Tariff of 1833. He also supported distributing revenue from public land sales to states as an emergency measure to manage their growing debts, even though this would reduce federal income. While Whigs generally favored high protectionist tariffs and federal funding for state infrastructure, there was enough overlap to attempt a compromise. The Distribution Act of 1841 created a distribution program with a 20% tariff ceiling, and a second bill raised tariffs to that figure on previously low-tax goods. Despite these measures, the federal government remained in dire fiscal straits by March 1842.

The economic depression worsened in early 1842, exacerbated by a looming deadline for a promised reduction in federal tariffs, a measure favored by Southern states that relied on open access to British markets for their cotton, but opposed by Northern states that benefited from protective tariffs for their nascent industries. Tyler reluctantly recommended overriding the 1833 Compromise Tariff and raising rates beyond 20%, which, under the previous agreement, would suspend the distribution program, with all revenues going to the federal government.

The defiant Whig Congress passed two bills in June 1842 that would raise tariffs and unconditionally extend the distribution program. Believing it improper to continue distribution while federal revenue shortages necessitated increasing tariffs, Tyler vetoed both bills, severing any remaining ties with the Whigs. Congress then combined the two into one bill, which Tyler vetoed again. Despite congressional dismay, the veto could not be overridden. As action was necessary, Whigs in Congress, led by House Ways and Means chairman Millard Fillmore, passed a bill (by a single vote in each house) restoring tariffs to 1832 levels and ending the distribution program. Tyler signed the Tariff of 1842 on August 30, while pocket vetoing a separate bill to restore distribution.

In May 1841, President Tyler appointed a commission, led by former governor and Mississippi U.S. Senator George Poindexter, to investigate alleged fraud in the New York Customs House under the previous administration of President Martin Van Buren. The commission uncovered fraudulent activities by Jesse D. Hoyt, the New York Collector. This investigation sparked controversy with the Whig-controlled Congress, which demanded to see the report and was upset that Tyler had paid the commission without congressional approval. Tyler defended his actions as his constitutional duty to enforce laws. When the report was completed on April 29, 1842, Tyler complied with the House's request to provide it. Poindexter's report proved embarrassing to both the Whig New York Collector and Hoyt. In response, Congress passed an appropriations law making it illegal for the president to appropriate money to investigators without congressional approval, an attempt to curb Tyler's power.

7.4. Foreign Policy Achievements

In stark contrast to his domestic policy struggles, Tyler's administration achieved significant successes in foreign affairs. He was a long-standing advocate of expansionism towards the Pacific and free trade, often invoking themes of national destiny and the spread of liberty to support these policies. His approach largely aligned with Jackson's earlier efforts to promote American commerce across the Pacific.

Eager to compete with Great Britain in international markets, Tyler dispatched lawyer Caleb Cushing to China, where he negotiated the Treaty of Wanghia in 1844. This treaty opened trade relations and established diplomatic ties with the Qing Empire, marking a significant step in America's engagement with Asia. In the same year, he sent Henry Wheaton as a minister to Berlin, where he negotiated a trade agreement with the Zollverein, a coalition of German states managing tariffs. However, the Whigs rejected this treaty, primarily as a show of hostility toward the Tyler administration. Tyler also advocated for an increase in military strength, which was praised by naval leaders who saw a marked increase in warships. The US Congress also considered opening trade with Joseon (Korea) in the same year as the Treaty of Wanghia but decided against it due to a lack of perceived immediate benefit.

In an 1842 special message to Congress, Tyler applied the Monroe Doctrine to Hawaii, dubbing it the "Tyler Doctrine." He warned Britain against interference there and initiated a process that eventually led to Hawaii's annexation by the United States.

7.4.1. Webster-Ashburton Treaty

A significant foreign crisis arose from an offshoot of the Aroostook War, which had ended in 1839, involving clashes between citizens of Maine and New Brunswick over a disputed 12,000-square-mile territory. Additionally, in 1841, an American ship, the Creole, transporting enslaved people from Virginia to New Orleans, experienced a mutiny. The ship was subsequently captured by the British and taken to the Bahamas, where the British refused to return the enslaved individuals to their enslavers, further escalating tensions.

Tyler's Secretary of State, Daniel Webster, with the President's full support, sought to resolve these issues with England. In 1842, the British dispatched emissary Lord Ashburton (Alexander Baring) to the United States. Negotiations quickly commenced and were productive.

The negotiations culminated in the Webster-Ashburton Treaty, which successfully determined the border between Maine and Canada. This issue had caused decades of tension and brought the two countries to the brink of war on several occasions, and the treaty significantly improved Anglo-American diplomatic relations. To address the issue of enslaved people, the U.S. and Britain agreed to grant a "right to visit" when ships from either nation were suspected of transporting enslaved individuals. Furthermore, a joint oceanic venture was established where a U.S. squadron and the British fleet would cooperate to stop the trafficking of enslaved people off African waters.

The issue of the Oregon border in the West was also discussed during these negotiations. At the time, Britain and the United States jointly occupied Oregon under the Convention of 1818. The British, with their Hudson's Bay Company fur trading posts, had a more significant presence than American settlers. During the negotiations, the British proposed dividing the territory along the Columbia River, which was unacceptable to Webster, who demanded that Britain pressure Mexico to cede California's San Francisco Bay to the United States. Ultimately, the Tyler administration was unsuccessful in concluding a treaty with the British to fix Oregon's boundaries.

7.4.2. Treaty of Wanghia

Tyler's administration pursued active diplomacy in Asia, seeking to expand American trade and influence. In 1844, he sent lawyer Caleb Cushing to China, where he successfully negotiated the Treaty of Wanghia. This treaty was the first formal diplomatic agreement between the United States and China. It opened several Chinese ports to American trade, granted Americans extraterritoriality in China, and established fixed tariffs for American goods. The treaty also allowed for the appointment of U.S. consuls in China and protected the rights of American missionaries. This agreement reflected the era's expansionist foreign policy, aiming to secure American commercial interests in the Pacific and compete with European powers, particularly Great Britain, which had recently concluded the Treaty of Nanking after the First Opium War. The Treaty of Wanghia laid the groundwork for future U.S.-China relations and was a significant achievement for Tyler's foreign policy.

7.4.3. Oregon and the West

Tyler held a strong interest in the vast territory west of the Rocky Mountains known as Oregon, which stretched from California's northern boundary (42° parallel) to Alaska's southern boundary (54°40′ north latitude). As early as 1841, he urged Congress to establish a chain of American forts from Council Bluffs, Iowa, to the Pacific to protect American settlers traveling along routes like the Oregon Trail.

Tyler's presidency saw two notable successes in western exploration, covering Oregon, Wyoming, and California. Captain John C. Frémont completed two significant scientific expeditions (1842 and 1843-1844) that effectively opened the West to American emigration. In his 1842 expedition, Frémont famously climbed a mountain in Wyoming, naming it Frémont's Peak (13.75 K ft), where he planted an American flag, symbolically claiming the Rocky Mountains and the West for the United States. His second expedition, beginning in 1843, followed the Oregon Trail into Oregon. Traveling west on the Columbia River, Frémont sighted the Cascade Range peaks and mapped Mount St. Helens and Mount Hood. In early March 1844, Frémont and his party descended the American River Valley to Sutter's Fort in Mexican California. There, he received a cordial greeting from John Sutter, observed the growing number of American settlers, and noted the weakness of Mexican authority over California. Upon Frémont's triumphant return from his second expedition, Tyler, at General Winfield Scott's request, promoted Frémont with a double brevet. Frémont's detailed reports and geographic maps from these expeditions, first published in 1845, were widely circulated and instrumental in encouraging westward migration.

7.5. Annexation of Texas

The annexation of the Republic of Texas became a central policy goal for Tyler soon after he became president. Recognizing his position as a president without a party, Tyler was emboldened to challenge party leaders like Clay and Van Buren, unconcerned about how Texas annexation might affect the Whigs or Democrats. Texas had declared independence from Mexico in the Texas Revolution of 1836, but Mexico still refused to acknowledge its sovereignty. The people of Texas actively sought to join the Union, but Presidents Jackson and Van Buren had been reluctant to inflame tensions over slavery by annexing another Southern state. Although Tyler intended annexation to be the focal point of his administration, Secretary Webster initially opposed it, convincing Tyler to focus on Pacific initiatives until later in his term.

Historians and scholars acknowledge Tyler's desire for western expansionism, but views differ regarding his motivations. Biographer Edward C. Crapol notes that Tyler, as a U.S. Representative during James Monroe's presidency, had suggested that slavery was a "dark cloud" over the Union and that its expansion could "disperse this cloud," potentially leading to gradual emancipation in older slave states like Virginia by thinning out the enslaved population. However, historian William W. Freehling argues that Tyler's official motivation for annexing Texas was to preempt suspected efforts by Great Britain to promote the emancipation of enslaved people in Texas, which would weaken the institution in the United States.

7.5.1. Early attempts

In early 1843, having completed the Webster-Ashburton Treaty and other diplomatic efforts, Tyler felt ready to pursue Texas annexation. Lacking a party base, he saw annexation as his only path to an independent election in 1844. For the first time in his career, he was willing to engage in "political hardball" to achieve it. As a trial balloon, he had his ally Thomas Walker Gilmer, then a U.S. Representative from Virginia, publish a letter defending annexation, which was well received. Despite his successful relationship with Webster, Tyler knew he needed a Secretary of State who supported the Texas initiative. With the British treaty work complete, he forced Webster's resignation and appointed Hugh S. Legaré of South Carolina as an interim successor.

With the help of newly appointed Treasury Secretary John C. Spencer, Tyler systematically replaced numerous officeholders with pro-annexation partisans, reversing his previous stance against patronage. He enlisted the help of political organizer Michael Walsh to build a political machine in New York. Journalist Alexander G. Abell wrote a flattering biography, Life of John Tyler, which was widely distributed to postmasters in exchange for an appointment as consul to Hawaii. Seeking to rehabilitate his public image, Tyler embarked on a nationwide tour in the spring of 1843. The positive public reception contrasted sharply with his ostracism in Washington. The tour centered on the dedication of the Bunker Hill Monument in Boston, Massachusetts. Shortly after the dedication, Tyler learned of Legaré's sudden death, which dampened the festivities and led him to cancel the remainder of the tour.

Tyler appointed Abel P. Upshur, a popular Secretary of the Navy and close adviser, as his new Secretary of State, and nominated Gilmer to fill Upshur's former office. Tyler and Upshur began quiet negotiations with the Texas government, promising military protection from Mexico in exchange for a commitment to annexation. Secrecy was crucial, as the Constitution required congressional approval for such military commitments. Upshur strategically planted rumors of possible British designs on Texas to garner support among Northern voters, who were generally wary of admitting a new pro-slavery state. By January 1844, Upshur informed the Texas government that he had secured a large majority of senators in favor of an annexation treaty. The Republic of Texas remained skeptical, and the finalization of the treaty extended until the end of February.

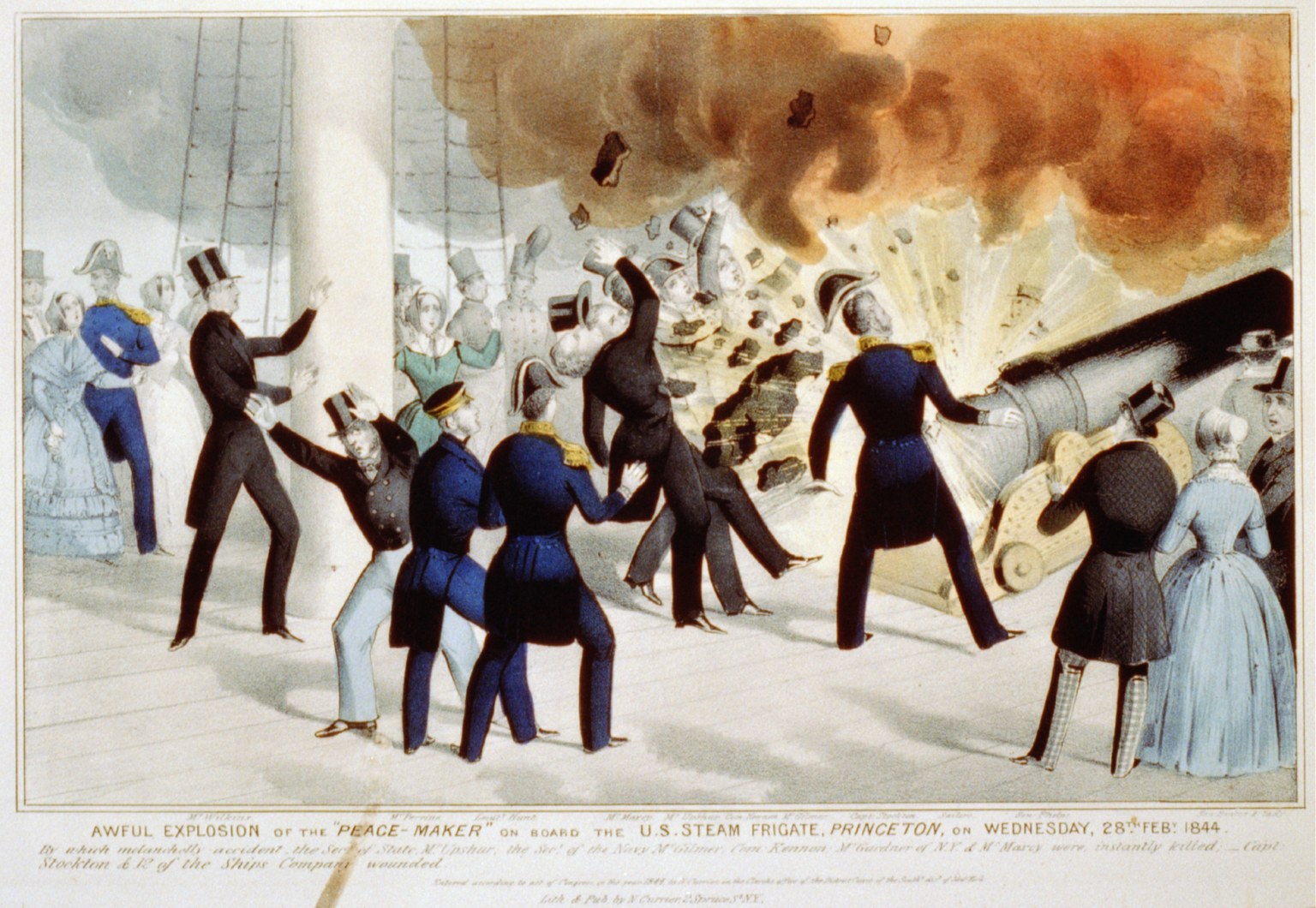

7.5.2. USS Princeton disaster

A ceremonial cruise down the Potomac River was held aboard the newly built USS Princeton (1843) on February 28, 1844, the day after the annexation treaty was completed. Aboard the ship were 400 guests, including Tyler and his cabinet, as well as the world's largest naval gun, the "Peacemaker." The gun was ceremoniously fired several times in the afternoon to the delight of onlookers, who then went below deck for a toast. Several hours later, Captain Robert F. Stockton was persuaded by the crowd to fire one more shot. As guests moved back to the deck, Tyler briefly paused to watch his son-in-law, William Waller, sing a ditty.

Suddenly, an explosion erupted from above: the gun had malfunctioned. Tyler was unharmed, having remained safely below deck, but a number of prominent individuals were killed instantly, including his crucial cabinet members, Gilmer and Upshur. Also killed or mortally wounded were Virgil Maxcy of Maryland, Representative David Gardiner of New York (whose daughter Julia would later marry Tyler), Commodore Beverley Kennon, Chief of Construction of the United States Navy, and Armistead, Tyler's enslaved body servant. The death of David Gardiner had a devastating effect on his daughter, Julia, who fainted and was carried to safety by the president himself. Julia later recovered from her grief and married Tyler on June 26, 1844.

For Tyler, any hope of completing the Texas plan before November (and with it, any hope of re-election) was instantly dashed. Historian Edward P. Crapol later wrote that "Prior to the Civil War and the assassination of Abraham Lincoln," the Princeton disaster "unquestionably was the most severe and debilitating tragedy ever to confront a President of the United States."

7.5.3. Ratification issue

In what the Miller Center of Public Affairs considers "a serious tactical error that ruined the scheme [of establishing political respectability for him]," Tyler appointed former Vice President John C. Calhoun as his Secretary of State in early March 1844. Tyler's friend, Virginia Representative Henry A. Wise, had, on his own volition, extended the offer to Calhoun as a self-appointed emissary of the president, and Calhoun accepted. When Wise informed Tyler of his action, the president was angry but felt the appointment had to stand. Calhoun, a leading advocate of slavery, faced resistance from abolitionists in his attempts to pass an annexation treaty.

When the text of the treaty was leaked to the public, it met strong political opposition from the Whigs, who opposed anything that might enhance Tyler's status, as well as from foes of slavery and those who feared a confrontation with Mexico, which had announced it would view annexation as a hostile act by the United States. Both Clay and Van Buren, the frontrunners for the Whig and Democratic nominations respectively, privately agreed to oppose annexation. Knowing this, Tyler was pessimistic when he sent the treaty to the Senate for ratification in April 1844.

Secretary of State Calhoun sent a controversial letter informing the British minister to the U.S. that the primary motivation for Texas annexation was to protect American slavery from British intrusion. The letter also controversially claimed that enslaved people in the Southern states were better off than free black individuals in the North and white laborers in England.

7.6. Election of 1844

Following his break with the Whigs in 1841, Tyler attempted to rejoin his old Democratic Party, but its members, particularly the followers of Van Buren, were unwilling to accept him. As the 1844 United States presidential election approached, Van Buren appeared to have a lock on the Democratic nomination, while Clay was certain to be the Whig candidate. With little chance of winning, Tyler's only way to salvage his presidential legacy was to threaten to run for president and force public acceptance of Texas annexation.

Tyler utilized his extensive presidential patronage power and formed a third party, the Tyler Party, drawing on the officeholders and political networks he had cultivated over the previous year. Multiple supportive newspapers across the country published editorials promoting his candidacy throughout the early months of 1844. Reports of meetings held nationwide suggested that support for the president was not limited to officeholders. As the Democratic Party held its presidential nomination in Baltimore, Maryland, Tyler's supporters, also in Baltimore, held signs reading "Tyler and Texas!" and, with high visibility and energy, gave Tyler their nomination on May 27, 1844. However, Tyler's party was loosely organized, failed to nominate a vice president, and lacked a formal platform.

The regular Democrats were compelled to include Texas annexation in their platform, but a bitter battle ensued for the presidential nomination. Ballot after ballot, Van Buren failed to secure the necessary super-majority of Democratic votes and gradually fell in the rankings. It was not until the ninth ballot that the Democrats turned to James K. Polk, a less prominent candidate who supported annexation. They found him perfectly suited for their platform, and he was nominated with two-thirds of the vote. Tyler considered his work vindicated and implied in an acceptance letter that annexation was his true priority rather than election.

In the spring of 1844, Tyler ordered Secretary of State John C. Calhoun to begin negotiations with Texas president Sam Houston for the annexation of Texas. To bolster annexation and deter Mexico, Tyler boldly ordered the U.S. Army to the Texas border on western Louisiana. He strongly supported Texas annexation.

7.6.1. Annexation achieved

Tyler was undeterred when the Whig-controlled Senate rejected his treaty by a vote of 16-35 in June 1844. He believed annexation could now be achieved by joint resolution rather than by treaty and made that request to Congress. Former President Andrew Jackson, a staunch supporter of annexation, persuaded Polk to welcome Tyler back into the Democratic Party and instructed Democratic editors to cease their attacks on him. Satisfied by these developments, Tyler withdrew from the race in August and endorsed Polk for the presidency. Polk's narrow victory over Clay in the November election was seen by the Tyler administration as a mandate for completing the resolution. Tyler announced in his annual message to Congress that "a controlling majority of the people and a large majority of the states have declared in favor of immediate annexation."

On February 26, 1845, the joint resolution that Tyler, the lame-duck president, had strongly lobbied for, passed Congress. The House approved a joint resolution offering annexation to Texas by a substantial margin, and the Senate approved it by a bare 27-25 majority. On his last day in office, March 3, 1845, Tyler signed the bill into law. Immediately afterward, Mexico broke diplomatic relations with the U.S., mobilized for war, and declared it would recognize Texas only if Texas remained independent. After some debate, Texas accepted the terms and entered the union on December 29, 1845, as the 28th state.

7.7. Domestic Affairs and Key Events

Beyond the major political and economic conflicts, Tyler's presidency addressed several other significant domestic issues and events, reflecting the challenges of governance during a period of national expansion and social change.

7.7.1. Dorr Rebellion

In May 1842, the Dorr Rebellion in Rhode Island escalated, prompting the governor and legislature to request federal troops to suppress it. The insurgents, led by Thomas Dorr, had armed themselves and sought to install a new state constitution, challenging Rhode Island's existing constitutional structure, which had been in place since 1663. Before the rebellion, Rhode Island was the only state that did not have universal white male suffrage.

Tyler called for calm from both sides and recommended that the governor expand the franchise to allow most men to vote. He promised that in the event of an actual insurrection, he would use force to aid the regular, or Charter, government. However, he made it clear that federal assistance would only be provided to put down an insurrection once violence had occurred, and would not be available before that point. After receiving reports from his confidential agents, Tyler concluded that the "lawless assemblages" had dispersed and expressed confidence in a "temper of conciliation as well as of energy and decision" without the need for federal forces. The rebels fled the state when the state militia marched against them, but the incident ultimately led to broader suffrage in Rhode Island, and a new state constitution was adopted in 1843.

7.7.2. Indian Affairs

Tyler's administration continued the complex and often contentious policies concerning Native American tribes. The Second Seminole War, a long, bloody, and inhumane conflict in Florida, was brought to an end in May 1842 by Tyler, who announced its conclusion to Congress. The Seminoles were the last remaining indigenous people in the South who had been induced to sign a fraudulent treaty in 1833, leading to their forced removal from their remaining lands. Under Chief Osceola, the Seminoles had resisted removal for a decade, harassed by U.S. troops. Tyler also expressed interest in the forced cultural assimilation of Native Americans.

In May 1841, Tyler signed the Preemption Act of 1841, allowing settlers to claim 160 acres (64.7 hectares) of public land by building a log cabin on it. This law significantly accelerated settlement in areas like Illinois, Wisconsin, Minnesota, and Iowa.

In May 1842, the House of Representatives demanded that President Tyler's Secretary of War, John Canfield Spencer, provide information from a U.S. Army investigation into alleged Cherokee frauds. In June, Tyler ordered Spencer not to comply, asserting executive privilege and arguing the matter was ex parte and against the public interest. The House responded with three resolutions, claiming its right to demand information from Tyler's cabinet and ordering the Army officer in charge of the investigation to turn over the information. Tyler did not respond until Congress returned from recess in January.

During Tyler's term, many regions saw significant developments. For example, Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, became a busy steel city, and Cincinnati, Ohio, boasted well-paved streets and schools requiring attendance for children aged six to ten.

7.8. Administration and Appointments

The intense battles between Tyler and the Whigs in Congress resulted in significant challenges for his administration, particularly concerning cabinet and judicial appointments. Without substantial support from either major party in Congress, many of his nominations were rejected, often without regard for the nominee's qualifications. This was largely unprecedented for cabinet nominees; prior to Tyler's term, only one cabinet nomination had ever failed (though James Madison withheld Albert Gallatin's nomination as Secretary of State in 1809 due to Senate opposition).

Tyler holds the record for the most cabinet nominees rejected by the Senate, with four: Caleb Cushing (Treasury), David Henshaw (Navy), James Porter (War), and James S. Green (Treasury). Henshaw and Porter served as recess appointees before their rejections. Tyler repeatedly renominated Cushing, who was rejected three times in a single day, March 3, 1843, the final day of the 27th Congress. No cabinet nomination failed after Tyler's term until Henry Stanbery's nomination as Attorney General was rejected by the Senate in 1868.

Tyler's cabinet saw frequent changes due to resignations and rejections.

| Office | Name | Term |

|---|---|---|

| Secretary of State | Daniel Webster | 1841-1843 |

| Abel P. Upshur | 1843-1844 | |

| John C. Calhoun | 1844-1845 | |

| Secretary of the Treasury | Thomas Ewing | 1841 |

| Walter Forward | 1841-1843 | |

| John Canfield Spencer | 1843-1844 | |

| George M. Bibb | 1844-1845 | |

| Secretary of War | John Bell | 1841 |

| John Canfield Spencer | 1841-1843 | |

| James Madison Porter | 1843-1844 | |

| William Wilkins | 1844-1845 | |

| Attorney General | John J. Crittenden | 1841 |

| Hugh S. Legaré | 1841-1843 | |

| John Nelson | 1843-1845 | |

| Postmaster General | Francis Granger | 1841 |

| Charles A. Wickliffe | 1841-1845 | |

| Secretary of the Navy | George Edmund Badger | 1841 |

| Abel P. Upshur | 1841-1843 | |

| David Henshaw | 1843-1844 | |

| Thomas Walker Gilmer | 1844 | |

| John Y. Mason | 1844-1845 |

7.9. Judicial Appointments

Two vacancies arose on the Supreme Court during Tyler's presidency, with the deaths of Justices Smith Thompson in 1843 and Henry Baldwin in 1844. Tyler, consistently at odds with Congress, including the Whig-controlled Senate, nominated several individuals to fill these seats. However, the Senate repeatedly voted against confirming his nominees, including John C. Spencer, Reuben Walworth (rejected three times), Edward King (rejected twice), and John M. Read. One cited reason for the Senate's actions was the hope that Clay would fill the vacancies after winning the 1844 presidential election. Tyler's four unsuccessful Supreme Court nominees are the most by any president.

Finally, in February 1845, with less than a month remaining in his term, Tyler's nomination of Samuel Nelson to Thompson's seat was confirmed by the Senate. Nelson, a Democrat, had a reputation as a careful and noncontroversial jurist, and his confirmation came as a surprise. Baldwin's seat remained vacant until James K. Polk's nominee, Robert Grier, was confirmed in 1846.

Tyler was able to appoint only six other federal judges, all to United States district courts.

| Court | Name | Term |

|---|---|---|

| U.S.S.C. | Samuel Nelson | 1845-1872 |

| E.D. Va. | James D. Halyburton | 1844-1861 |

| D. Ind. | Elisha M. Huntington | 1842-1862 |

| E.D. La. W.D. La. | Theodore H. McCaleb | 1841-1861 |

| D. Vt. | Samuel Prentiss | 1842-1857 |

| E.D. Pa. | Archibald Randall | 1842-1846 |

| D. Mass. | Peleg Sprague | 1841-1865 |

7.10. Impeachment Attempt

Shortly after his tariff vetoes, Whigs in the House of Representatives initiated the body's first impeachment proceedings against a president. The congressional ill will towards Tyler stemmed from the basis for his vetoes; until the presidency of the Whigs' archenemy Andrew Jackson, presidents rarely vetoed bills, and then only on grounds of constitutionality. Tyler's actions were seen as a challenge to Congress's presumed authority to make policy. Tyler had vetoed a total of ten congressional bills (six regular and two pocket vetoes), a number comparable to Jackson's twelve (five regular and seven pocket vetoes), and significantly more than Martin Van Buren's one pocket veto.

Congressman John Minor Botts, a staunch opponent of Tyler, introduced an impeachment resolution on July 10, 1842. Botts levied nine formal articles of impeachment for "high crimes and misdemeanors" against Tyler. Six of the charges pertained to political abuse of power, while three concerned alleged misconduct in office. Botts also called for a nine-member committee to investigate Tyler's behavior, with the expectation of a formal impeachment recommendation. Henry Clay considered this measure prematurely aggressive, favoring a more moderate progression toward Tyler's "inevitable" impeachment. Botts's resolution was tabled until January 1843 when it was rejected by a vote of 127 to 83, with some Whigs finding the accusations too absurd and voting with Democrats to defeat it.

A House select committee headed by John Quincy Adams, an ardent abolitionist who disliked slaveholders like Tyler, condemned Tyler's use of the veto and assailed his character. While the committee's report did not formally recommend impeachment, it clearly established the possibility, and in August 1842, the House endorsed the committee's report. Adams sponsored a constitutional amendment to change both houses' two-thirds requirement for overriding vetoes to a simple majority, but neither house approved it. The Whigs were unable to pursue further impeachment proceedings in the subsequent 28th Congress because they retained a majority in the Senate but lost control of the House in the 1842 elections. On the last full day of Tyler's term in office, March 3, 1845, Congress overrode his veto of a minor bill relating to revenue cutters-the first override of a presidential veto in U.S. history.

Tyler was not entirely without support in Congress. A small group of House members, known as the "Corporal's Guard," led by fellow Virginian Congressman Henry A. Wise, supported Tyler throughout his struggles with the Whigs. As a reward for his loyalty, Tyler appointed Wise U.S. Minister to Brazil in 1844.

8. Post-Presidency and Civil War Stance

After leaving office, Tyler returned to private life, but his later years were profoundly shaped by the escalating sectional tensions that led to the Civil War, ultimately defining his controversial legacy.

8.1. Retirement and Later Life

Tyler left Washington with the conviction that the newly inaugurated President Polk had the best interests of the nation at heart. He retired to his Virginia plantation, originally named Walnut Grove, located on the James River in Charles City County. He famously renamed it Sherwood Forest, a reference to the folk legend Robin Hood, signifying his feeling of being "outlawed" by the Whig Party. He took his farming responsibilities seriously, working diligently to maintain high yields. In 1847, his neighbors, largely Whigs, appointed him to the minor office of overseer of roads in an attempt to mock him. To their dismay, he treated the job with seriousness, frequently summoning his neighbors to provide their enslaved people for road work and insisting on carrying out his duties even after they asked him to stop.

The former president spent his time in a manner common to Virginia's First Families, attending parties, visiting, or being visited by other aristocrats, and spending summers at the family's seaside home, "Villa Margaret." In 1852, Tyler happily rejoined the ranks of the Virginia Democratic Party and maintained an interest in political affairs. However, he rarely received visits from his former allies and was not sought out as an adviser. Occasionally requested to deliver public speeches, Tyler spoke at the unveiling of a monument to Henry Clay. He acknowledged their past political battles but spoke highly of his former colleague, whom he had always admired for bringing about the Compromise Tariff of 1833.

8.2. Role in the Civil War

After John Brown's raid on Harpers Ferry in 1859 ignited fears of abolitionist attempts to free enslaved people or incite slave rebellions, several Virginia communities organized militia units or re-energized existing ones. Tyler's community formed a cavalry troop and a home guard company, with Tyler chosen to command the home guard troops with the rank of captain.

On the eve of the American Civil War, Tyler re-entered public life as the presiding officer of the Washington Peace Conference, held in Washington, D.C., in February 1861. This conference was an effort to prevent the conflict from escalating, seeking a compromise to avoid civil war even as the Confederate Constitution was being drafted at the Montgomery Convention. Despite his leadership role, Tyler ultimately opposed the conference's final resolutions. He felt they were biased towards free state delegates, did not adequately protect the rights of slave owners in the territories, and would do little to bring back the lower South and restore the Union. He voted against the conference's seven resolutions, which were sent to Congress for approval as a proposed Constitutional amendment in late February 1861.

On the same day the Peace Conference began, local voters elected Tyler to the Virginia Secession Convention. He presided over its opening session on February 13, 1861. Tyler abandoned hope of compromise and came to view secession as the only viable option, predicting that a clean split of all Southern states would not result in war. In mid-March, he spoke against the Peace Conference resolutions. On April 4, he voted for secession even when the convention initially rejected it. On April 17, after the attack on Fort Sumter and Abraham Lincoln's call for troops, Tyler voted with the new majority for secession. He headed a committee that negotiated the terms for Virginia's entry into the Confederate States of America and helped set the pay rate for military officers. On June 14, Tyler signed the Ordinance of Secession, and one week later, the convention unanimously elected him to the Provisional Congress of the Confederate States. Tyler was seated in the Confederate Congress on August 1, 1861, and served until just before his death in 1862. In November 1861, he was elected to the Confederate House of Representatives but died before it could assemble.

Tyler's decision to support the Confederacy led to some strong criticisms. If the Confederacy is considered a foreign entity, Tyler is seen by some as the only former U.S. president to have died in a foreign country. He is also considered by some to be the only person accused of treason after serving as president.

9. Death

Throughout his life, Tyler suffered from poor health, with frequent colds during winter as he aged. On January 12, 1862, after complaining of chills and dizziness, he vomited and collapsed. Despite treatment, his health did not improve, and he planned to return to Sherwood Forest by January 18. The night before, he began suffocating, and his wife Julia summoned his doctor. Just after midnight, Tyler took a sip of brandy and told his doctor, "Doctor, I am going," to which the doctor replied, "I hope not, Sir." Tyler then said, "Perhaps it is best." John Tyler died in his room at the Exchange Hotel in Richmond shortly thereafter, most likely due to a stroke. He was 71 years old.

Tyler's death was the only one in presidential history not to be officially recognized in Washington, D.C., due to his allegiance to the Confederate States of America. He had requested a simple burial, but Confederate President Jefferson Davis orchestrated a grand, politically pointed funeral, portraying Tyler as a hero to the new nation. Consequently, at his funeral, the coffin of the tenth president of the United States was draped with a Confederate flag; he remains the only U.S. president ever laid to rest under a flag not of the United States. Tyler was seen as more loyal to Virginia and his own principles than to the Union of which he had been president.

Tyler was buried in Hollywood Cemetery in Richmond, Virginia, near the gravesite of President James Monroe. The city of Tyler, Texas, was named for him due to his role in the annexation of Texas. In 1915, Congress dedicated a monument to Tyler at Hollywood Cemetery, where he is interred beside his second wife.

10. Historical Reputation and Legacy

Tyler's presidency has elicited highly divided responses from political commentators and historians. His historical standing is generally low, with many scholars describing him as a "hapless and inept chief executive" whose presidency was "seriously flawed" and "one of the least successful." A 2021 C-SPAN survey of historians ranked Tyler 39th out of 44 U.S. presidents.

10.1. Achievements and Praises

Despite the prevailing negative assessments, some historians have offered praise for certain aspects of Tyler's presidency. Richard P. McCormick, in 2002, bucked the trend by stating that "contrary to accepted opinion, John Tyler was a strong President. He established the precedent that the vice president, on succeeding to the presidential office, should be president. He had firm ideas on public policy, and he was disposed to use the full authority of his office." McCormick concluded that Tyler "conducted his administration with considerable dignity and effectiveness."

Tyler's assumption of complete presidential powers upon Harrison's death "set a hugely important precedent," according to the University of Virginia's Miller Center of Public Affairs. His successful insistence that he was the full president, not merely a caretaker or acting president, served as a model for the succession of seven other vice presidents (Millard Fillmore, Andrew Johnson, Chester A. Arthur, Theodore Roosevelt, Calvin Coolidge, Harry S. Truman, and Lyndon B. Johnson) throughout the 19th and 20th centuries. The legality and propriety of Tyler's action were finally affirmed in 1967 when codified in the Twenty-fifth Amendment to the United States Constitution.

Some scholars have particularly praised Tyler's foreign policy. Dan Monroe credits him with "achievements like the Webster-Ashburton treaty which heralded the prospect of improved relations with Great Britain, and the annexation of Texas, which added millions of acres to the national domain." Edward P. Crapol argued that Tyler "was a stronger and more effective president than generally remembered," while Robert Seager II described him as "a courageous, principled man, a fair and honest fighter for his beliefs. He was a president without a party." Author Ivan Eland, in his 2008 book Recarving Rushmore, rated Tyler as the best president of all time based on criteria of peace, prosperity, and liberty. Louis Kleber noted that Tyler brought integrity to the White House when many in politics lacked it, refusing to compromise his principles to avoid his opponents' anger.

Norma Lois Peterson suggests that Tyler's general lack of success as president was due to external factors that would have affected any occupant of the White House. Chief among these was Henry Clay, who tolerated no opposition to his grand economic vision for America. In the aftermath of Jackson's determined use of executive power, the Whigs desired a president subservient to Congress, and Clay treated Tyler as a subordinate. Tyler resented this, leading to the inter-branch conflict that dominated his presidency. Pointing to his foreign policy advances, Peterson deemed Tyler's presidency "flawed ... but ... not a failure."

10.2. Criticisms and Controversies

Despite some achievements, John Tyler's presidency is largely viewed critically, primarily due to his profound conflicts with Congress, his stance on slavery, and his ultimate alignment with the Confederacy. His frequent use of the veto power, particularly against Whig-backed legislation for a national bank and higher tariffs, led to an unprecedented level of political animosity. This resulted in the mass resignation of his cabinet and his expulsion from the Whig Party, leaving him politically isolated as "the man without a party." The House of Representatives even initiated the first impeachment proceedings against a U.S. president, though the resolution ultimately failed. His cabinet was often dubbed a "disaster" by critics.

A significant criticism of Tyler stems from his position as a slaveholder and his staunch defense of states' rights, which he applied to the issue of slavery. While he personally regarded slavery as an evil, he never freed any of his enslaved people and believed the federal government lacked the authority to abolish the institution. His pursuit of the annexation of Texas, which became a slave state, further exacerbated sectional tensions and contributed to the growing national divide over slavery, which ultimately led to the Civil War.

Perhaps the most damaging aspect of Tyler's legacy is his role in the secession crisis and his decision to support the Confederacy. After chairing the Washington Peace Conference in an attempt to avert war, he abandoned hope of compromise and advocated for Virginia's immediate secession. He signed the Ordinance of Secession and was elected to the Provisional Confederate Congress, serving until his death. His funeral, orchestrated by Confederate President Jefferson Davis, saw his coffin draped with a Confederate flag, making him the only U.S. president buried under a flag other than that of the United States. This act of allegiance to the Confederacy is seen by many as a betrayal of his loyalty to the Union he once led, overshadowing his earlier contributions. As Edward P. Crapol argues, "Tyler's historical reputation has yet to fully recover from that tragic decision to betray his loyalty and commitment to what he had once defined as 'the first great American interest'-the preservation of the Union."

While academics have both praised and criticized Tyler, the general American public has little awareness of him. Several writers have portrayed Tyler as among the nation's most obscure presidents. As Seager remarked: "His countrymen generally remember him, if they have heard of him at all, as the rhyming end of a catchy campaign slogan."

11. Personal Life and Family

John Tyler is notable for having fathered more children than any other American president. His personal life was marked by two marriages and a large family, alongside his views and practices regarding slavery. He was known for his calm demeanor in social relations, and enjoyed writing romantic poems and playing the violin. He was quite tall and thin, with blue eyes, beautiful wavy brown hair, large hands, thin lips, and a high forehead, with cheeks that sagged from high cheekbones down to a small chin. He was an Episcopalian.

11.1. Marriages and Children

Tyler's first wife was Letitia Christian (November 12, 1790 - September 10, 1842), whom he married on March 29, 1813. They had eight children:

- Mary (1815-1847)

- Robert (1816-1877)

- John (1819-1896)

- Letitia (1821-1907)

- Elizabeth (1823-1850)

- Anne (1825-1825)

- Alice (1827-1854)

- Tazewell (1830-1874)

Letitia suffered a paralytic stroke when her husband became president and died in the White House in September 1842. For a period, Tyler's daughter-in-law, Priscilla Cooper Tyler, served as the White House hostess.

On June 26, 1844, Tyler married Julia Gardiner (July 23, 1820 - July 10, 1889) in New York. Julia was 30 years his junior, and their marriage made him the first sitting president to marry while in office. This marriage drew criticism, including ridicule over the age difference and the perceived excessive cost of the wedding. They had seven children:

- David (1846-1927)

- John Alexander (1848-1883)

- Julia (1849-1871)

- Lachlan (1851-1902)

- Lyon (1853-1935)

- Robert Fitzwalter (1856-1927)

- Margaret Pearl (1860-1947)

In total, John Tyler fathered 15 children, more than any other American president. The couple resided at Tyler's Sherwood Forest plantation in Virginia.

Although his family was dear to him, Tyler was often away from home for extended periods during his political career. He chose not to seek reelection to the House of Representatives in 1821 partly due to the financial demands of educating his growing family, noting that his plantation was more profitable when he could manage it himself. By the time he entered the Senate in 1827, he had resigned himself to spending part of the year away from his family, though he sought to maintain close ties through letters.

Tyler and his son Lyon both remarried much younger women and fathered children at advanced ages. As a result, Tyler's youngest daughter, Pearl, did not die until 1947, 157 years after her father's birth. As of 2024, Tyler still has one living grandson through Lyon, Harrison Ruffin Tyler, born in 1928, making him the earliest former president with a living grandchild. Harrison Ruffin Tyler maintains the family home, Sherwood Forest Plantation, in Charles City County, Virginia.

11.2. Views on Slavery

John Tyler was a slaveholder, owning at one point up to 40 enslaved people at Greenway. While he regarded slavery as an evil and did not attempt to justify it, he never freed any of his enslaved people. Tyler considered slavery a matter of states' rights, believing that the federal government lacked the authority to abolish it. The living conditions of his enslaved people are not extensively documented, but historians generally surmise that he cared for their well-being and refrained from physical violence against them.

In December 1841, the abolitionist publisher Joshua Leavitt made unsubstantiated allegations that Tyler had fathered several sons with his enslaved women and later sold them. While a number of black families today maintain a belief in their descent from Tyler, there is no evidence to support such genealogical claims. At least four of his sons served in the government or military forces of the Confederacy. His grandson, Robert Tyler Jones, by his daughter Mary, joined Company K of the 53rd Virginia Infantry Regiment on June 25, 1861, and was wounded on July 3, 1863, while taking part in Pickett's Charge as a color-bearer in the Army of Northern Virginia during the Battle of Gettysburg.

11.3. Financial Status

Tyler's personal net worth is estimated to have exceeded 50.00 M USD when adjusted for inflation to modern standards (based on peak valuation circa 2020). However, he became indebted during the Civil War and died with a greatly reduced fortune. He was often short on money, and reportedly had to borrow funds to travel from Williamsburg to Washington D.C. after learning of President Harrison's death.