1. Life and Education

Jan Baptist van Helmont's life was marked by extensive education, a critical approach to established knowledge, and a dedication to empirical research, which was largely enabled by his personal circumstances.

1.1. Birth and Family

Jan Baptist van Helmont was born on January 12, 1580, in Brussels, which was then part of the Spanish Netherlands. He was the youngest of five children born to Christiaen van Helmont, a public prosecutor and a member of the Brussels council, and Maria (van) Stassaert. His parents had married in 1567 at the St. Michael and Gudula Cathedral.

1.2. Education and Early Career

Van Helmont received his education at the Old University of Leuven, where he pursued a wide range of studies. He began with the arts and classics, then delved into theology and mysticism at a Jesuit school. However, he found dissatisfaction in these fields, leading him to turn his attention to medicine. He interrupted his formal studies to embark on several years of extensive travel through Switzerland, Italy, France, Germany, and England. This period of travel broadened his perspective and deepened his critical view of conventional knowledge.

Upon returning to his homeland, van Helmont formally obtained his medical degree in 1599, though he later pursued and received his doctoral degree in medicine in 1609. He practiced medicine in Antwerp during the devastating Great Plague of 1605. His experiences during this epidemic informed his later medical writings, including a book titled De Peste (On Plague). His personal encounter with scabies further solidified his distrust in traditional Galenic medicine. When conventional purgatives worsened his condition, he reportedly recovered only by applying treatments based on Paracelsian medicine, which was not mainstream at Leuven University at the time. This event led him to discard many of his medical texts, a decision he later regretted not having formalized by burning them. Despite his criticisms, he initially served as a lecturer in surgery at his alma mater.

1.3. Marriage and Beginning of Research

In 1609, Jan Baptist van Helmont married Margaret van Ranst, a woman from a wealthy noble family. This marriage provided him with financial independence, as his wife's inheritance allowed him to retire early from his medical practice. They settled in Vilvoorde, a town near Brussels, where they raised six or seven children. Freed from the necessities of a professional career, van Helmont was able to fully dedicate himself to chemical experiments and scientific research, which he continued until his death in 1644.

2. Scientific Contributions

Jan Baptist van Helmont's scientific contributions were marked by a blend of empirical experimentation, innovative conceptualization, and a unique philosophical framework that challenged the prevailing scientific and medical paradigms of his time.

2.1. Philosophical and Methodological Approach

Van Helmont was deeply influenced by the alchemist Paracelsus, adopting many of his ideas, particularly the focus on chemical processes in the body. However, he also critically rejected what he perceived as errors in the works of most contemporary authorities, including Paracelsus himself, and fiercely criticized the ancient Galenic medicine and Aristotle's four-element theory.

He championed a modern scientific methodology rooted in empiricism and experimentation. Van Helmont believed that true understanding of God's creations could only be achieved through divine power and human abilities, emphasizing the importance of direct observation and empirical experience over scholasticism and dialectics. He was deeply skeptical of ancient Greek philosophy's reliance on abstract reasoning. While he believed in the existence of the philosopher's stone, his rigorous approach to experimentation aligned him with contemporary proponents of the "new learning" such as Santorio Santori, William Harvey, Galileo Galilei, and Francis Bacon. This commitment to empirical inquiry laid foundational principles for later scientific advancements.

2.2. Discoveries in Chemistry

Van Helmont's work significantly advanced the field of chemistry, notably through his pioneering work on gases and his early insights into the conservation of mass.

2.2.1. Introduction of the "Gas" Concept

Jan Baptist van Helmont is widely regarded as the founder of pneumatic chemistry. He was the first to recognize that there were specific types of gases distinct from atmospheric air. He coined the term "gas" from the Greek word chaos (χᾰοςkhaosGreek, Ancient).

He diligently worked to identify and classify various gases. One of his most notable identifications was "gas sylvestre," which is now known as carbon dioxide. He observed that this gas was produced by burning charcoal and was identical to the gas released during the fermentation of must (grape juice), a gas he also noted could render the air in caves unbreathable. He further posited the existence of at least four types of gases, which are believed to correspond to modern carbon dioxide, carbon monoxide, nitrous oxide, and methane. The introduction of the term "gas" provided a crucial conceptual tool that significantly facilitated the development of modern chemistry.

2.2.2. Conservation of Mass and Element Theory

Van Helmont was a keen observer of nature, and his meticulous analysis of experimental data demonstrated an early understanding of the conservation of mass. He provided experimental evidence that matter is not annihilated during chemical reactions. In one notable experiment, he burned 62 lb (62 lb) of charcoal, which produced only 1 lb (1 lb) of ash. He deduced that the remaining 61 lb (61 lb) must have been transformed into other substances, primarily water and specific "fermented" gases, which were released into the air. This observation suggested that these substances were inherent components of the original material, merely exposed through combustion.

Regarding his element theory, van Helmont challenged both Aristotle's four classical elements (earth, air, fire, water) and Paracelsus's tria prima (salt, sulfur, mercury). He explicitly denied that fire was an element and argued that earth was not one because it could be reduced to water. For van Helmont, air and water were the two fundamental, primitive elements of the world. However, he believed that only water possessed the unique capability of undergoing chemical change to produce all other substances, while air primarily served as a physical medium. He supported this theory by noting that fish could live in water, and that biological matter could be dissolved into water by acids. He also believed this concept aligned with the biblical account of creation.

2.3. Physiological and Medical Research

Van Helmont's inquiries extended into human physiology and medicine, where he proposed innovative theories on digestion and vital forces, challenging prevailing medical practices.

2.3.1. Theory of Digestion

Van Helmont extensively studied the process of digestion. He critically examined earlier ideas, such as the notion that food was digested by the body's internal heat. He challenged this by questioning how cold-blooded animals could survive if this were true. His own groundbreaking theory proposed that digestion was facilitated by a chemical reagent, or "ferment," within the body, particularly in the stomach. This concept was remarkably similar to the modern understanding of an enzyme. He also posited that food was digested by stomach acid and subsequently absorbed through the walls of the intestines. Van Helmont further elaborated on the digestive process by describing six distinct stages of digestion, demonstrating a sophisticated early understanding of this complex biological function.

2.3.2. Concepts of 'Archeus' and 'Blas'

To explain the fundamental activities of life, van Helmont introduced the concepts of 'Archeus' and 'Blas', forming a vitalistic perspective. He described the 'archeus' as the "chief workman" or "aura vitalis seminum, vitae directrix" (the vital air of seeds, the director of life). He believed the archeus consisted of the conjunction of "vital air" (as matter) with a "seminal likeness," which he described as an "inward spiritual kernel" containing the fruitfulness of the seed, with the visible seed being merely its "husk." He also believed that beyond the archeus, there existed a "sensitive soul," which he considered the outer layer of the immortal mind. According to his theory, before the Fall of Man, the archeus was directly controlled by the immortal mind. However, with the Fall, humans acquired the sensitive soul and lost their immortality, as the immortal mind could no longer remain in the body once the sensitive soul perished.

In addition to the archeus, van Helmont conceived of other governing agencies, which he did not always clearly distinguish from it. Among these was 'blas' (motion), defined as the "vis motus tam alterivi quam localis" (a twofold motion, both local and alterative). This meant 'blas' encompassed both natural motion and motion that could be altered or was voluntary. He categorized several kinds of 'blas', including blas humanum (blas of humans), blas of stars, and blas meteoron (blas of meteors). He stated that meteors "constare gas materiâ et blas efficiente" (consist of their matter Gas and their efficient cause Blas, both motive and altering).

2.3.3. Magnetic Healing and Other Medical Views

Van Helmont held unique medical views and practices, including the use of magnetism for healing. He published a tract titled De magnetica vulnerum curatione (On the Magnetic Healing of Wounds) in 1621. In this work, he criticized the prevalent belief in "weapon salve"-the notion that wounds could be healed by treating the weapon that caused them, rather than the wound itself. He also notably opposed conventional medical practices such as bloodletting, advocating for more observation-based and chemically informed treatments. His advocacy for these unconventional ideas, particularly his inability to scientifically explain the efficacy of his "miraculous cream," drew suspicion from traditional medical authorities and later contributed to his persecution by religious institutions.

2.4. Willow Tree Experiment

Van Helmont's willow tree experiment is considered one of the earliest quantitative studies in plant nutrition and growth, and a significant milestone in the history of biology. Although it was conducted around 1600, its results were only published posthumously in his magnum opus, Ortus Medicinae (1648). The experiment might have been inspired by similar works by Santorio Santori, published in Ars de statica medicina (1614).

For his experiment, van Helmont meticulously measured 200 lb (200 lb) (approx. 201 lb (91 kg)) of dried soil and placed it in a large pot. He then planted a small willow tree seedling, weighing 5 lb (5 lb) (approx. 4.4 lb (2 kg)), into the soil. For five years, he carefully nurtured the willow tree, providing it with nothing but distilled water. He prevented any additional soil or foreign matter from entering the pot.

After five years of observation, the willow tree had grown significantly, gaining approximately 164 lb (164 lb) (approx. 163 lb (74 kg)) in weight. Crucially, when he re-measured the soil, he found that its weight had decreased by only 2.0 oz (57 g) (approx. 0.12 lb (0.12 lb)). From these precise measurements, van Helmont logically deduced that the substantial increase in the tree's mass could not have come from the soil, but rather almost entirely from the water he had supplied. He concluded that plants derived their substance from water, not from the earth. This experiment marked a crucial shift from speculative reasoning to empirical evidence in plant physiology and laid a fundamental groundwork for future research into photosynthesis and plant growth.

2.5. Views on Spontaneous Generation

Despite his innovative experimental methods, Jan Baptist van Helmont adhered to the ancient belief in spontaneous generation, the idea that living organisms could arise from non-living matter under specific conditions. He even provided specific "recipes" for creating animals. For instance, he famously described a method for generating mice by placing a dirty cloth, particularly one soaked with human sweat, along with wheat grains in a container for 21 days. He also proposed that scorpions could be spontaneously generated by placing basil leaves between two bricks and leaving them in direct sunlight. His personal notes indicate that he might have attempted to carry out these experiments himself. He considered human sweat as a vital force necessary for this life-generating process.

3. Religious and Philosophical Views

Jan Baptist van Helmont was a devout Catholic, yet his profound religious faith intertwined uniquely with his scientific pursuits and mystical inclinations. He frequently experienced visions throughout his life, placing great significance on them. He even attributed his choice to pursue a medical profession to a conversation he believed he had with the Archangel Raphael. His writings explored the concept of imagination as a celestial, and potentially magical, force.

While van Helmont expressed skepticism towards certain specific mystical theories and practices, he was reluctant to dismiss the influence of "magical forces" as explanations for various natural phenomena. This stance, particularly highlighted in his 1621 paper on sympathetic principles, contributed to the suspicions he incurred from the Church. His "Christian philosophy" was significantly influenced by the work of Paracelsus, especially the concepts outlined in Paracelsus's Astronomia Magna, written around 1537-1538. Van Helmont believed that understanding the divine creation was only possible through divine grace and human capacity, often guided by the words of the Bible. He critically viewed the prevalent natural philosophy of ancient Greece and the dialectical methods of medieval scholasticism, emphasizing direct experimentation as the pathway to understanding God's work in the world.

4. Persecution and Later Life

Jan Baptist van Helmont's scientific and medical views, particularly those touching upon mystical or "magical" forces, led to significant suspicion and eventual persecution from the Catholic Church. In 1621, he published his tract De magnetica vulnerum curatione (On the Magnetic Healing of Wounds), in which he not only discussed the use of a "miraculous cream" for healing but also vehemently criticized the common belief in "weapon salve" (treating a wound by treating the weapon that caused it).

This publication drew the ire of Jean Roberti, a Jesuit scholar and a critic of van Helmont's views. Roberti, unable to reconcile the effects of van Helmont's 'miraculous cream' with conventional explanations, accused him of using "magic." Roberti successfully convinced the Inquisition to scrutinize van Helmont's writings. As a result, van Helmont was formally accused by the Inquisition. In 1634, he was arrested and placed under house arrest, a confinement that lasted for several weeks. The ensuing trial, however, never reached a definitive conclusion. He was neither formally sentenced nor fully rehabilitated, and the legal proceedings remained unresolved even at the time of his death. Consequently, a ban on the publication of his works was imposed, which persisted until two years after his death.

5. Major Writings

Jan Baptist van Helmont's insights and experimental findings were primarily disseminated through his major written works, though many were published posthumously due to the Church's ban.

His magnum opus, Ortus medicinae, vel opera et opuscula omnia (The Origin of Medicine, or Complete Works), was compiled and edited by his son, Franciscus Mercurius van Helmont, and published in Amsterdam by Lodewijk Elzevir in 1648, four years after van Helmont's death. This comprehensive work was based on, but not limited to, the material found in his 1644 Dutch publication, Dageraad ofte Nieuwe Opkomst der Geneeskunst (Daybreak, or the New Rise of Medicine). Some scholars suggest that Ortus medicinae may also contain contributions from his son, who was also a dedicated researcher. This book provided a detailed exposition of his chemical, physiological, and medical theories, including his theories on digestion, the concept of gases, and the willow tree experiment.

Other notable works include:

- De Peste (On Plague), written around 1605, reflecting his experiences during the Antwerp plague.

- De magnetica vulnerum curatione (On the Magnetic Healing of Wounds), published in 1621, which led to his conflict with the Inquisition.

- Febrium doctrina inaudita (Unheard-of Doctrine of Fevers), published in 1642.

- Opuscula medica inaudita (Unheard-of Medical Works), published in 1644.

These writings, especially Ortus medicinae, served as a critical foundation for subsequent developments in chemistry and medicine, despite the initial suppression of his ideas.

6. Legacy and Assessment

Jan Baptist van Helmont's work had a profound and lasting impact on the development of several scientific disciplines, marking him as a significant figure in the history of science.

6.1. Impact on the History of Science

Van Helmont is often considered a pivotal figure in the transition from alchemy to modern chemistry. His introduction of the term "gas" and his pioneering work in identifying different types of gases laid the foundation for pneumatic chemistry. He was among the first to emphasize the importance of quantitative methods in chemical experiments, notably by using a balance to measure matter transformations, thereby foreshadowing the concept of the conservation of mass.

His experimental approach, which prioritized observation and measurement over ancient dogmas, significantly influenced the Scientific Revolution. In physiology, his theory of digestion, which proposed a chemical "ferment" (similar to enzymes) and the role of stomach acid, was far ahead of its time. His meticulous willow tree experiment was a landmark study in botany and plant nutrition, demonstrating that plants derived their mass primarily from water, which was a crucial step towards understanding photosynthesis. He also introduced the concept of "saturation" in the context of acid-base combinations, further contributing to chemical vocabulary.

6.2. Honors and Commemoration

Jan Baptist van Helmont's contributions have been recognized posthumously in various ways. In 1875, the Belgian botanist Alfred Cogniaux honored him by naming a genus of flowering plants from South America, Helmontia, belonging to the Cucurbitaceae family, in his recognition. A monument dedicated to Jan Baptist van Helmont has also been erected in his birthplace, Brussels, commemorating his significant scientific achievements.

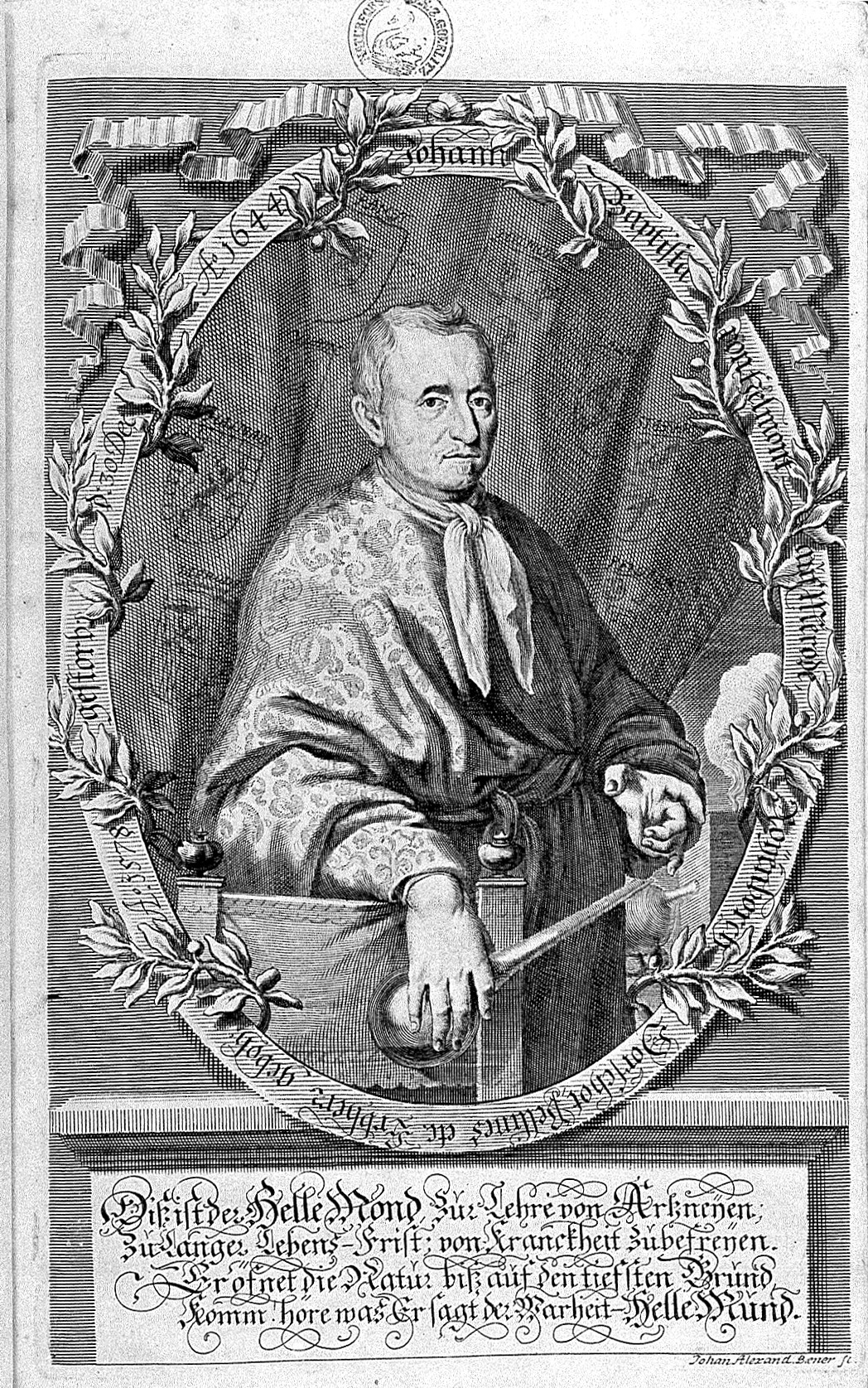

6.3. Disputed Portrait

In 2003, historian Lisa Jardine put forward the hypothesis that a portrait held in the collections of the Natural History Museum, London, which had been traditionally identified as John Ray, might actually represent Robert Hooke. However, Jardine's theory was subsequently disproved by William B. Jensen of the University of Cincinnati and German researcher Andreas Pechtl of Johannes Gutenberg University of Mainz. Their research conclusively demonstrated that the portrait in question actually depicts Jan Baptist van Helmont, resolving the long-standing misidentification.