1. Overview

Jack Benny (born Benjamin Kubelsky; February 14, 1894 - December 26, 1974) was a highly influential American entertainer who rose from a modest career as a violin player on the vaudeville circuit to become one of the leading figures in 20th-century entertainment. He achieved immense popularity through his comedic work in radio, television, and film. Benny was renowned for his exceptional comic timing and his unique ability to evoke laughter with a prolonged pause or a single, exasperated expression, such as his signature "Well!" His radio and television programs, which were popular from 1932 until his death in 1974, significantly influenced the development of the sitcom genre. In his comedic persona, Benny portrayed himself as a miser who played the violin poorly and perpetually claimed to be 39 years old, regardless of his actual age.

2. Early life

Jack Benny's early life was marked by his musical beginnings, his family background, and his gradual transition from a musician to a comedian.

2.1. Birth and childhood

Benny was born Benjamin Kubelsky on February 14, 1894, at Mercy Hospital in Chicago, Illinois, and was raised in nearby Waukegan, Illinois. He was the son of Jewish immigrants: Meyer Kubelsky (1864-1946), who was a saloon owner and later a haberdasher who had emigrated from Poland, and Naomi Emma Sachs (1869-1917), who had emigrated from Lithuania. At his father's insistence, Benny began taking violin lessons at the age of six. He was quickly recognized as a child prodigy, though he personally disliked practicing the instrument. His music teacher was Otto Graham Sr., a neighbor and the father of the renowned football player Otto Graham. By the age of 14, Benny was already performing in dance bands and his high school orchestra.

2.2. Education

Benny struggled with his formal education, often described as a dreamer and a poor student. He was eventually expelled from high school. His attempts at business school were also unsuccessful, as were his efforts to join his father's business ventures.

2.3. Early career and activities

In 1911, Benny began his professional career playing the violin in local vaudeville theaters, earning 7.5 USD a week. He was joined on the circuit by Ned Miller, a young composer and singer. The same year, Benny performed in the same theater as the young Marx Brothers. Their mother, Minnie Marx, was impressed by Benny's violin playing and invited him to join her sons' act. However, Benny's parents refused to let their 17-year-old son travel on the road. Despite this, it marked the beginning of a long-standing friendship between Benny and the Marx Brothers, particularly Zeppo Marx.

The following year, Benny formed a vaudeville musical duo with pianist Cora Folsom Salisbury. This partnership drew legal pressure from the famous violinist Jan Kubelik, who was concerned that the young vaudevillian with a similar name would damage his reputation. Consequently, Benjamin Kubelsky agreed to change his name to Ben K. Benny. After Salisbury left the act, Benny found a new pianist, Lyman Woods, and renamed their act "From Grand Opera to Ragtime". They performed together for five years, gradually incorporating comedy elements into their show. Their performance at the Palace Theater, known as the "Mecca of Vaudeville", was not well received.

In 1917, Benny briefly left show business to join the United States Navy during World War I. He frequently entertained his fellow sailors with his violin playing. On one occasion, his violin performance was met with boos from the audience. Prompted by fellow sailor and actor Pat O'Brien, Benny ad-libbed his way out of the situation, leaving the audience laughing. This incident led to more comedy spots in revues, where he excelled and earned a reputation as both a comedian and a musician. Benny attained the rank of Seaman First Class.

Shortly after the war, Benny developed a one-man act titled "Ben K. Benny: Fiddle Funology". He again faced legal pressure, this time from Ben Bernie, a "patter-and-fiddle" performer, regarding his stage name. As a result, he adopted the nickname "Jack", which he had been called by fellow sailors. By 1921, the violin had largely become a prop in his act, and his understated comedy took center stage.

Benny had several romantic relationships, including one with dancer Mary Kelly, who was introduced to him by Gracie Allen. Kelly's devoutly Catholic family compelled her to decline Benny's marriage proposal because he was Jewish.

In 1922, Benny accompanied Zeppo Marx to a Passover Seder in Vancouver, where he met 17-year-old Sadie Marks. Their first encounter was awkward, as Benny attempted to leave during Sadie's violin performance. They met again in 1926, and Jack, having no recollection of their previous meeting, was immediately captivated by her. They married the following year. Sadie was working in the hosiery section of the May Company on Broadway Boulevard in downtown Los Angeles, directly across from the Orpheum Theater where Jack was performing. Sadie proved to be a natural comedienne when she was called upon to fill in for the "dumb girl" character in one of Benny's routines. Adopting the stage name Mary Livingstone, Sadie collaborated with Benny throughout most of his career. They later adopted a daughter, Joan (1934-2021). Sadie's older sister, Babe, often became the subject of jokes regarding unattractive or masculine women, while her younger brother, Hilliard, would later produce Benny's radio and television programs.

In 1929, Benny's agent, Sam Lyons, convinced Irving Thalberg, a film producer at Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer, to watch Benny perform at the Orpheum Theatre in Los Angeles. Benny subsequently signed a five-year contract with MGM, leading to his first film role in The Hollywood Revue of 1929. His next film, Chasing Rainbows, was not successful, and after several months, Benny was released from his contract. He returned to Broadway, appearing in Earl Carroll's Vanities. Although initially skeptical about the potential of radio, Benny soon became eager to enter the new medium. In 1932, following a four-week nightclub engagement, he was invited to appear on Ed Sullivan's radio program. During this debut, he famously delivered his first radio line: "This is Jack Benny talking. There will be a slight pause while you say, 'Who cares?'"

3. Radio career

Jack Benny transitioned from a relatively minor vaudeville performer to a national sensation with The Jack Benny Program, a weekly radio show that aired from 1932 to 1948 on NBC and from 1949 to 1955 on CBS. It consistently ranked among the most highly rated programs throughout its run.

Benny's extensive radio career began on April 6, 1932, when he auditioned for the N. W. Ayer & Son agency and their client, Canada Dry, at the NBC Commercial Program Department. Bertha Brainard, head of the division, commented, "We think Mr. Benny is excellent for radio and, while the audition was unassisted as far as orchestra was concerned, we believe he would make a great bet for an air program." Benny later recalled in 1956 that Ed Sullivan had invited him to guest on his program in 1932, and subsequently, "the agency for Canada Dry ginger ale heard me and offered me a job."

Sponsored by Canada Dry ginger ale, Benny's first radio show, The Canada Dry Program, premiered on May 2, 1932. It was broadcast on Mondays and Wednesdays on the NBC Blue Network and featured George Olsen and his orchestra. After a few initial shows, Benny hired Harry Conn as a writer. The program continued on the Blue Network for six months until October 26, before moving to CBS on October 30, where it aired on Thursdays and Sundays. With Ted Weems leading the band, Benny remained on CBS until January 26, 1933. Canada Dry chose not to renew Benny's contract after attempting to replace Conn with Sid Silvers, who would have also received a co-starring role. Unlike later iterations of the Benny show, The Canada Dry Program was primarily a musical program.

Benny then appeared on The Chevrolet Program, which aired on the NBC Red Network from March 17, 1933, until April 1, 1934. It initially broadcast on Fridays, replacing Al Jolson, and then moved to Sunday nights in the fall. The show featured Benny and Mary Livingstone alongside Frank Black's orchestra and vocalists James Melton and, later, Frank Parker. The program concluded after General Motors' president insisted on a purely musical format. Benny continued with his sponsor General Tire on Fridays through the end of September.

The show made a significant network switch to CBS on January 2, 1949, as part of CBS president William S. Paley's notable "raid" on NBC talent during 1948-1949. It remained on CBS for the rest of its radio run, concluding on May 22, 1955. CBS later aired repeat episodes from 1956 to 1958 under the title The Best of Benny.

The following table lists selected radio appearances by Jack Benny:

| Year | Program | Episode/source |

|---|---|---|

| 1937 | Lux Radio Theatre | Brewster's Millions |

| 1938 | Lux Radio Theatre | Seven Keys to Baldpate |

| 1942 | Screen Guild Players | Parent by Proxy |

| 1943 | Screen Guild Players | Love Is News |

| 1946 | Lux Radio Theatre | Killer Cates |

| 1951 | Suspense | Murder in G-Flat |

| 1954 | Suspense | The Face Is Familiar |

4. Television career

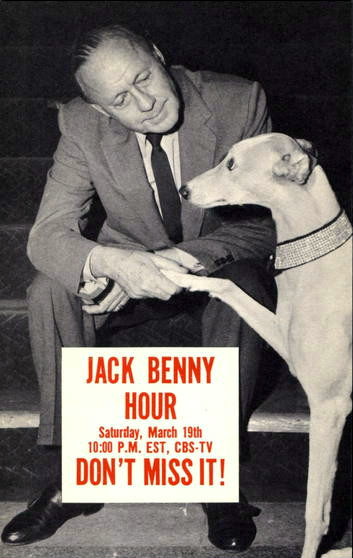

Jack Benny made his television debut in 1949 on local Los Angeles station KTTV, then a CBS affiliate. The network television version of The Jack Benny Program aired from October 28, 1950, to 1965, with all but the final season broadcast on CBS. Initially, the show was scheduled as a series of five "specials" during the 1950-1951 season. It then appeared every six weeks for the 1951-1952 season, every four weeks for the 1952-1953 season, and every three weeks in 1953-1954. For the 1953-1954 season, half of the episodes were broadcast live, while the other half were filmed during the summer to allow Benny to continue his radio show commitments. From the fall of 1954 to 1960, the program aired every other week, and from 1960 to 1965, it became a weekly show.

On March 28, 1954, Benny co-hosted General Foods 25th Anniversary Show: A Salute to Rodgers and Hammerstein alongside Groucho Marx and Mary Martin. In September 1954, CBS premiered Chrysler's Shower of Stars, co-hosted by Jack Benny and William Lundigan. This show enjoyed a successful run from 1954 until 1958. Both of these television shows frequently overlapped with Benny's ongoing radio program. In fact, the radio show often alluded to its television counterparts, with Benny frequently signing off the radio broadcast by saying, "Well, good night, folks. I'll see you on television."

When Benny transitioned to television, audiences discovered that his verbal comedic talent was perfectly complemented by his controlled repertoire of deadpan facial expressions and gestures. The television program largely mirrored the radio show, with several radio scripts being re-adapted for the visual medium, a common practice for radio shows moving to television. However, the television version incorporated additional visual gags. Lucky Strike served as the sponsor for the program. Benny performed his opening and closing monologues before a live studio audience, which he considered essential for the timing of his material. As was common in other television comedy shows, a laugh track was sometimes added to "sweeten" the soundtrack, particularly when the live studio audience missed certain close-up visual comedy due to cameras or microphones obstructing their view.

Television viewers became accustomed to the infrequent appearances of Mary Livingstone, who suffered from a severe case of stage fright that did not diminish even after performing with Benny for two decades. Consequently, Livingstone rarely appeared on the television show. In fact, during the final few years of the radio show, she pre-recorded her lines, and her daughter, Joan, stood in for the live tapings, with Mary's lines later edited into the broadcast, replacing Joan's. Mary Livingstone permanently retired from show business in 1958, following the example of her friend Gracie Allen.

Benny's television program relied more heavily on guest stars and less on his regular cast members compared to his radio program. The only radio cast members who regularly appeared on the television show were Don Wilson and Eddie "Rochester" Anderson. Singer Dennis Day made sporadic appearances, and Phil Harris had left the radio program in 1952, though he did make a guest appearance on the television show. Bob Crosby, who replaced Phil Harris on the radio, frequently appeared on television through 1956. A frequent guest on the show was the Canadian-born singer-violinist Gisele Mackenzie.

As a comedic stunt, Benny made a 1957 appearance on the then-wildly popular $64,000 Question. His chosen category was "Violins," but after correctly answering the first question, Benny opted not to continue, leaving the show with only 64 USD. The host, Hal March, famously gave Benny the prize money from his own pocket. March later made an appearance on Benny's show the same year.

Benny had a remarkable ability to attract guest stars who rarely, if ever, appeared on television. In 1953, both Marilyn Monroe and Humphrey Bogart made their television debuts on Benny's program. Another notable guest star was Rod Serling, who appeared in a spoof of The Twilight Zone. In this sketch, Benny finds himself in his own house where no one recognizes him, leading him to run away in a panic. Serling then breaks the fourth wall to remark that there's no need to worry about Benny, as anyone who has been 39 years old for as long as he has is clearly a citizen of the "Twilight Zone."

In 1964, Walt Disney was a guest on the show, primarily to promote his production of Mary Poppins. Benny famously persuaded Disney to give him over 110 free admission tickets to Disneyland for his friends, plus one for his wife. Later in the show, Disney seemingly sent his pet tiger after Benny as a comedic revenge, at which point Benny opened his umbrella and soared above the stage like Mary Poppins.

CBS canceled The Jack Benny Program in 1964, citing Benny's perceived lack of appeal to the younger demographic the network was beginning to target. He then moved to NBC, his original network, in the fall, but was out-rated by CBS's Gomer Pyle, U.S.M.C. NBC subsequently dropped Benny at the end of that season. He continued to make occasional television specials into the 1970s, with his last one airing in January 1974. Benny also made two appearances on The Lucy Show: once as a plumber who coincidentally resembled Jack Benny, and in 1967, in an episode titled "Lucy Gets Jack Benny's account," where Lucy gives Jack a tour of his new money vault. In the late 1960s, Benny starred in a series of commercials for Texaco Sky Chief gasoline, utilizing his "stingy" television persona. In these commercials, he consistently told the attendant, played by Dennis Day, "I'll take a gallon," after being implored, "Mr. Benny, won't you please fill up?"

In his unpublished autobiography, I Always Had Shoes (portions of which were later incorporated by his daughter, Joan Benny, into her memoir of her parents, Sunday Nights at Seven), Benny stated that he, not NBC, made the decision to end his weekly television series in 1965. He claimed that while the ratings were still very good (citing a figure of approximately 18 million viewers per week, though he qualified this by saying he never fully trusted ratings services), advertisers were complaining that commercial time on his show cost nearly twice as much as on most other programs. Furthermore, he had grown weary of what he called the "rate race." Thus, after three decades of weekly programs on radio and television, Jack Benny concluded his career at its peak. Benny himself shared Fred Allen's ambivalence about television, though perhaps not to the same extent. He remarked, "By my second year in television, I saw that the camera was a man-eating monster... It gave a performer close-up exposure that, week after week, threatened his existence as an interesting entertainer."

In a joint appearance with Phil Silvers on Dick Cavett's show, Benny recalled advising Silvers not to pursue a television career. However, Silvers disregarded Benny's advice and went on to win several Emmy Awards for his portrayal of Sergeant Bilko on the popular series The Phil Silvers Show.

5. Film career

Jack Benny also had a significant career in film, appearing in several notable productions. These included the Academy Award-winning The Hollywood Revue of 1929, Broadway Melody of 1936 (where he played a benign nemesis to Eleanor Powell and Robert Taylor), and George Washington Slept Here (1942). His most acclaimed film roles were in Charley's Aunt (1941) and To Be or Not to Be (1942). He and Mary Livingstone also appeared as themselves in Ed Sullivan's Mr. Broadway (1933).

Benny frequently parodied contemporary films and genres on his radio program. The 1940 film Buck Benny Rides Again notably featured all the main radio characters in a humorous Western parody adapted from the program's skits. The commercial failure of another of his cinematic vehicles, The Horn Blows at Midnight, became a long-running gag on both his radio and television programs, although modern viewers might not find the film as disappointing as the jokes suggested.

It has been rumored that Benny had an uncredited cameo role in Casablanca. This claim was supported by a contemporary newspaper article and an advertisement, and reportedly appeared in the Casablanca press book. When asked about this in his "Movie Answer Man" column, film critic Roger Ebert initially responded, "It looks something like him. That's all I can say," but later wrote in a subsequent column, "I think you're right."

Benny was also caricatured in several Warner Brothers cartoons. He appeared as Casper the Caveman in Daffy Duck and the Dinosaur (1939), and as "Jack Bunny" in I Love to Singa (1936), Slap Happy Pappy (1940), and Goofy Groceries (1941). He was caricatured as himself in Malibu Beach Party (1940). Perhaps the most memorable of these animated appearances was in The Mouse that Jack Built (1959), where director Robert McKimson engaged Benny and his actual cast members-Mary Livingstone, Eddie "Rochester" Anderson, and Don Wilson-to voice mouse versions of their characters. Mel Blanc, the usual Warner Brothers cartoon voice artist, reprised his vocal role as the perpetually aging Maxwell, always on the verge of collapse with a "phat-phat-bang!" In the cartoon, Benny and Livingstone decide to spend their anniversary at the Kit-Kat Club, only to discover it is located inside the mouth of a live cat. Before the cat can devour the mice, Benny awakens from his dream. He then shakes his head, smiles wryly, and mutters, "Imagine, me and Mary as little mice." He then glances towards the cat lying on a throw rug in a corner and sees his and Livingstone's cartoon alter egos scampering out of the cat's mouth. The cartoon concludes with a classic Benny look of befuddlement. It was rumored that Benny requested a copy of the finished film in lieu of monetary compensation for his voice work.

Benny also made a cameo appearance in the 1963 comedy film It's a Mad, Mad, Mad, Mad World.

6. Personal life

Jack Benny's personal life was closely intertwined with his professional career, particularly through his marriage to Mary Livingstone and the involvement of his family members.

Benny married Sadie Marks in 1927, who would later become known professionally as Mary Livingstone. Their collaboration became a cornerstone of Benny's career. They later adopted a daughter, Joan (1934-2021). Beyond Mary, other family members also played roles in Benny's professional life; Mary's older sister, Babe, was often the subject of comedic jokes about unattractive or masculine women, while Mary's younger brother, Hilliard, later served as a producer for Benny's radio and television work.

7. Later years and death

After his regular broadcasting career concluded, Jack Benny continued to perform live as a violinist and as a stand-up comedian. In the 1960s, he was the headlining act at Harrah's Lake Tahoe, often performing with trumpeter Harry James, clown Emmett Kelly, and singer Ray Vasquez.

Benny made one of his final television appearances on January 23, 1974, as a guest on The Tonight Show Starring Johnny Carson, where he recreated several classic radio skits with Mel Blanc. This appearance occurred the day before his final television special aired. Benny was preparing to star in the film version of Neil Simon's The Sunshine Boys when his health began to fail later that year. He persuaded his longtime best friend, George Burns, to take his place on a nightclub tour while he prepared for the film. Burns ultimately had to replace Benny in the film as well, a role for which he went on to win an Academy Award.

Benny made one last appearance on The Tonight Show on August 21, 1974, with Rich Little serving as guest host. According to his own statement during that appearance, Benny was still expecting to star in The Sunshine Boys. He also made several appearances on The Dean Martin Celebrity Roast in his final 18 months, roasting figures such as Ronald Reagan, Johnny Carson, Bob Hope, and Lucille Ball, in addition to being roasted himself in February 1974. The Lucille Ball roast, which was his last public performance, aired on February 7, 1975, several weeks after his death.

In October 1974, Benny canceled a performance in Dallas after experiencing a dizzy spell accompanied by numbness in his arms. Despite a battery of tests, his ailment could not be determined. When he complained of stomach pains in early December, an initial test yielded no findings, but a subsequent examination revealed that he had inoperable pancreatic cancer. Benny fell into a coma at his home on December 22, 1974. While in the coma, he was visited by close friends, including George Burns, Bob Hope, Frank Sinatra, Johnny Carson, John Rowles, and then-Governor Ronald Reagan. He died on December 26, 1974, at the age of 80.

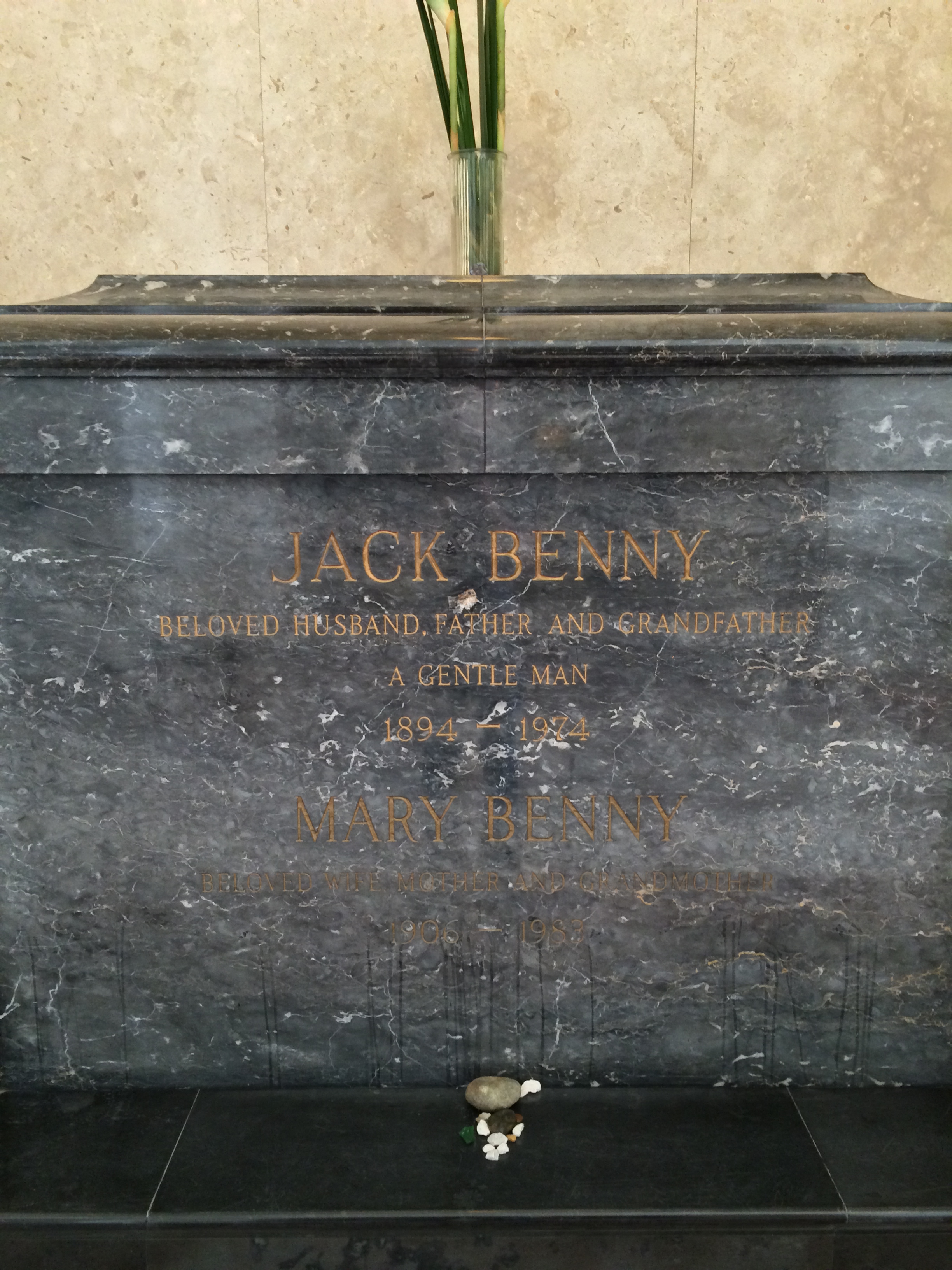

His funeral, held at Hillside Memorial Park Cemetery in Culver City, California, on December 29, was attended by 1,800 people, making it the largest funeral for a Hollywood personality since Harry Cohn in 1958. George Burns, Benny's best friend for over fifty years, attempted to deliver a eulogy but broke down shortly after beginning and was unable to continue. Bob Hope also delivered a eulogy, stating, "For a man who was the undisputed master of comedic timing, you would have to say this is the only time when Jack Benny's timing was all wrong. He left us much too soon." The pallbearers included Frank Sinatra, Mervyn LeRoy, Gregory Peck, Milton Berle, Billy Wilder, Irving Fein, Leonard Gershe, Fred de Cordova, and Armand Deutsch. Benny was interred in the main mausoleum of the cemetery. His will famously arranged for a single long-stemmed red rose to be delivered to his widow, Mary Livingstone, every day for the remainder of her life. Livingstone died eight and a half years later on June 30, 1983, at the age of 78.

Reflecting on his successful life, Benny summarized it by stating: "Everything good that happened to me happened by accident. I was not filled with ambition nor fired by a drive toward a clear-cut goal. I never knew exactly where I was going."

8. Legacy and evaluation

Jack Benny left a profound and lasting impact on the world of comedy and entertainment, influencing generations of performers and shaping the landscape of radio and television. His unique comedic style, characterized by his self-deprecating persona and masterful use of timing, cemented his cultural significance.

Upon his death, Benny's family donated his personal, professional, and business papers, along with a collection of his television shows, to the University of California, Los Angeles (UCLA). In his honor, the university established the Jack Benny Award for Comedy in 1977, which recognizes outstanding individuals in the field of comedy. Johnny Carson was the inaugural recipient of this award. Benny also donated a Stradivarius violin, which he had purchased in 1957, to the Los Angeles Philharmonic Orchestra. He famously quipped about the instrument, "If it isn't a 30.00 K USD Strad, I'm out 120 USD."

8.1. Honors and tributes

Jack Benny received numerous honors and tributes throughout his career and posthumously, recognizing his immense contributions to entertainment.

In 1960, Benny was inducted into the Hollywood Walk of Fame with three stars, a testament to his versatility across different media. His stars for television and motion pictures are located at 6370 and 6650 Hollywood Boulevard, respectively, while his star for radio is at 1505 Vine Street. He was inducted into the Television Hall of Fame in 1988 and the National Radio Hall of Fame in 1989. He was also honored with induction into the Broadcasting and Cable Hall of Fame.

In 1972, Benny was inducted as a laureate of The Lincoln Academy of Illinois and was awarded the Order of Lincoln, the state's highest honor, by the governor of Illinois in the area of the performing arts.

A Tribute To Jack Benny, a special program written and narrated by Charles Kuralt, was aired on CBS-TV on the day of his funeral, and it included coverage of the funeral service itself.

When the price of a standard first-class U.S. postal stamp was increased to 0.39 USD in 2006, fans petitioned for a Jack Benny stamp to honor his stage persona's perpetual age of 39. The U.S. Postal Service had previously issued a stamp depicting Benny in 1991 as part of a booklet of stamps honoring comedians; however, that stamp was issued at the then-current rate of 0.29 USD.

Jack Benny Middle School in Waukegan, Illinois, is named after Benny, and its motto proudly reflects his famous statement: "Home of the '39ers." A statue of Benny holding his violin stands in downtown Waukegan, further commemorating his legacy in his hometown.

The British comedian Benny Hill, whose original name was Alfred Hawthorne Hill, changed his name as a direct tribute to Jack Benny. Benny was also notably mentioned by Doc Brown in the film Back to the Future, when Doc humorously speculated about who would be the United States Secretary of the Treasury by 1985, disbelieving that Ronald Reagan could be President of the United States.