1. Overview

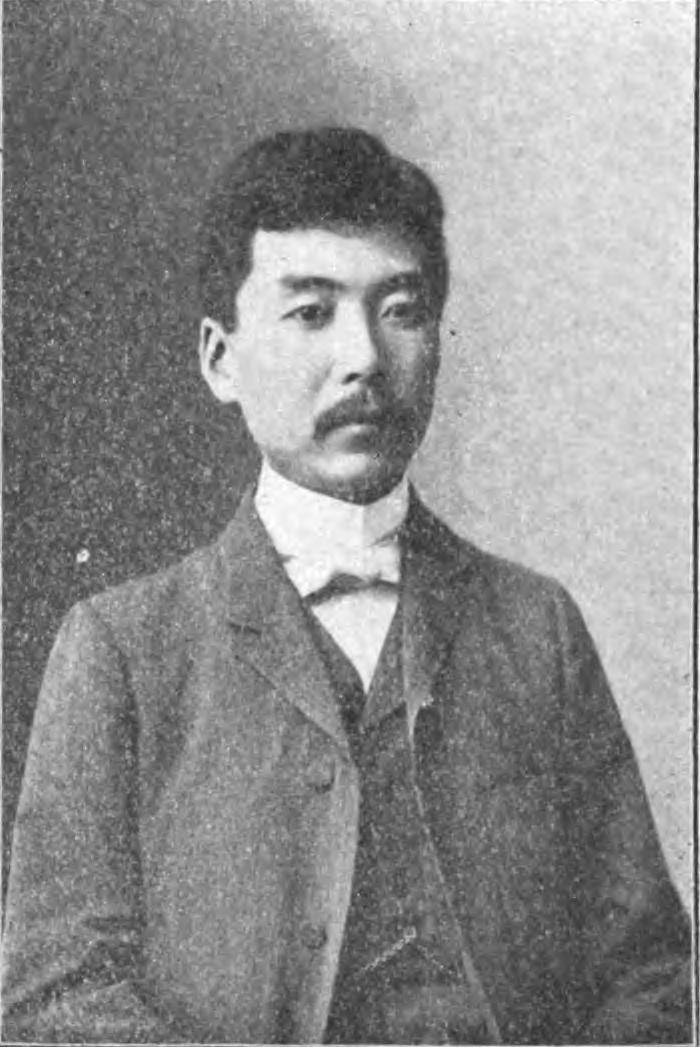

Ikeda Shigeaki (池田 成彬Ikeda ShigeakiJapanese), also known as Seihin Ikeda, was a prominent Japanese politician, cabinet minister, and businessman who played a significant role in Japan's economic and political landscape during the early 20th century. Born into a samurai family in 1867, Ikeda rose through the ranks of the powerful Mitsui Zaibatsu, where he spearheaded banking reforms and modernization efforts, eventually becoming its de facto head. His career was marked by both significant achievements in financial management and controversies, including his involvement in the Showa Financial Crisis and the contentious "dollar buying incident," which drew widespread public criticism and highlighted the social impact of corporate actions.

Beyond his business acumen, Ikeda served in key public offices, including the 14th Governor of the Bank of Japan, the 38th Minister of Finance, and the 16th Minister of Commerce and Industry. He was known for his pragmatic and pro-Anglo-American stance, which often put him at odds with the increasingly militaristic factions within the Japanese government, particularly his strong opposition to Japan's entry into the Pacific War. Notably, Ikeda was also involved in the Fugu Plan, advocating for the resettlement of Jewish refugees in Japan, a humanitarian effort that reflected his progressive views on human rights and international relations. Following World War II, despite being briefly detained as a suspected war criminal, he cooperated with the Allied occupation authorities in the dissolution of the zaibatsu, a move that, while controversial among his former colleagues, underscored his commitment to Japan's post-war reconstruction and democratic reforms. His life reflects a complex interplay of economic power, political influence, and a nuanced perspective on social responsibility during a turbulent era.

2. Early Life and Education

Ikeda Shigeaki's formative years were shaped by his samurai lineage and a rigorous education that prepared him for a distinguished career in finance and public service.

2.1. Birth and Background

Ikeda Shigeaki was born on August 15, 1867, in Yonezawa Domain (modern-day Yonezawa City, Yamagata Prefecture), during the final year of the Bakumatsu period. He was the eldest son of Ikeda Nariaki, a notable samurai and a retainer of the Yonezawa Domain, who served as a rusui (resident officer) in Edo. His father's role influenced Ikeda's early upbringing, where he studied Chinese classics (漢学kangakuJapanese) at Yonezawa Middle School, a local han school. Around 1880, at the age of 13, Ikeda moved to Tokyo, continuing his studies in Confucianism and Chinese classics at private academies such as Arima School, Koinagai Kohachiro's Rensei-juku, and under Nakajo Masatsune, who also tutored prominent figures like Hirata Tosuke and Goto Shinpei. He later attended Shinbungakusha.

2.2. Education and Study Abroad

Ikeda initially aimed to enter Tokyo Imperial University but faced challenges due to his lack of English language proficiency. After being recommended by an acquaintance, he enrolled in the special course (Bekka) at Keio University in 1888, graduating in July of that year. Upon learning of the establishment of a new university department at Keio, he shifted his focus from the Imperial University entrance examination. For about 18 months, he received private English tutoring from a British instructor, which enabled him to secure admission into the newly established Department of Economics (理財科rizaikaJapanese) at Keio University in January 1890. His proficiency in English proved crucial when he was recommended by Harvard University professor Arthur Knapp, who was stationed at Keio, to study abroad. Ikeda then pursued higher education at Harvard University in the United States from 1890 to 1895, spending five years immersed in Western thought and banking practices. During his time in the U.S., he maintained correspondence with Obata Atsujiro and Kadono Ikunoshin. After completing his studies, he returned to Japan and briefly joined the Jiji Shimpo newspaper as an editorial writer, but he resigned after only three weeks. The exact reasons for his departure are debated, with theories suggesting dissatisfaction with his salary, the unestablished nature of the newspaper business, or a desire to apply his Harvard knowledge and experience in a more impactful field.

3. Career at Mitsui Zaibatsu

Ikeda Shigeaki's career at the Mitsui Zaibatsu was extensive, marked by his rapid ascent from a bank employee to the de facto head of one of Japan's most powerful conglomerates, where he initiated significant reforms and modernization efforts.

3.1. Entry into Mitsui Bank and Career Progression

In December 1895, Ikeda began his career at Mitsui Bank, then undergoing significant reforms led by its director, Nakamigawa Hirojiro. Starting in the investigations department, he was later assigned to the Osaka branch and subsequently became the director of the Ashikaga branch. During this early period, he introduced innovative banking practices, including proposals for the underwriting of municipal bonds for Osaka and new deposit agreements between banks. In 1898, he was sent back to Europe and the United States to study banking modernization, returning in 1900. Upon his return, he rapidly ascended the hierarchy within the Mitsui Zaibatsu, becoming assistant manager of the sales department at the head office in 1900 and then manager in 1904. In the same year, he married Tsya, the eldest daughter of Nakamigawa Hirojiro, a key figure in the Mitsui Zaibatsu. In 1911, he was appointed managing director when Mitsui Bank transitioned from a partnership (合名会社gōmei kaishaJapanese) to a stock company, a reform he actively helped establish. He remained in the managing director position for 23 years, becoming the principal managing director in 1919. The capital increase and public listing of Mitsui Bank's shares in August 1919 were reportedly realized through Ikeda's initiative.

3.2. Banking Reforms and Modernization

Ikeda was a driving force behind the modernization of banking practices within Mitsui. He introduced new concepts such as the "call system" and actively worked on the underwriting of municipal bonds, notably for Osaka City. He also played a crucial role in establishing interbank deposit agreements, which were innovative for their time. His overseas study in 1898 specifically focused on learning about modern banking operations in the West. A significant achievement was his instrumental role in the 1911 transformation of Mitsui Bank from a partnership to a joint-stock company, a move that brought it in line with modern corporate structures. He further pushed for the public listing of Mitsui Bank's shares in 1919, a decision that increased transparency and access to capital, reflecting his commitment to modern financial principles.

3.3. Leadership of Mitsui Zaibatsu

In 1932, Ikeda became the de facto head of the Mitsui Zaibatsu, assuming the role of principal managing director of Mitsui Gomei Kaisha, the holding company of the conglomerate. This appointment came at the request of Mitsui Takahiro, the head of the Mitsui family, though Ikeda sometimes clashed with the family. To address public criticism and deflect the animosity from right-wing groups following financial controversies, Ikeda initiated significant organizational reforms. He established the Mitsui Hōonkai, a philanthropic organization, and channeled substantial donations into various charity and social projects, aiming to present a "zaibatsu conversion" (財閥転向zaibatsu tenkōJapanese) and improve Mitsui's public image.

Furthermore, Ikeda undertook a major overhaul of Mitsui's top management. He effectively removed members of the Mitsui family, including Mitsui Takakata, Mitsui Takayasu, and Mitsui Takahiro, from the direct management of the zaibatsu's key companies, making them public by offering their stock on the Tokyo Stock Exchange. He also recommended the retirement of influential figures like Yasukawa Yunosuke, who had a tendency towards autocratic management. In 1936, Ikeda introduced a mandatory retirement system for executives and employees across Mitsui Gomei and its six direct subsidiaries, setting the retirement age at 70. Demonstrating his commitment to this new policy, he himself retired from Mitsui at the age of 70 in 1937, setting an example of discipline for the management.

4. Financial Crisis and Controversies

Ikeda Shigeaki's career was not without significant challenges and public scrutiny, particularly regarding his involvement in major financial upheavals and controversial business decisions.

4.1. Showa Financial Crisis and the Bank of Taiwan

In March 1927, Ikeda came under intense criticism following the collapse of Suzuki Shoten, a major trading company, and the subsequent Showa Financial Crisis. The crisis was triggered by the Bank of Taiwan's inability to recover large loans extended to Suzuki Shoten, which had been struggling due to the post-war economic recession. The Bank of Taiwan itself had become heavily reliant on loans from the Bank of Japan and the Deposit Bureau of the Ministry of Finance to overcome previous crises in the 1920s. It was revealed that Ikeda, in an effort to protect Mitsui's assets, had precipitously withdrawn funds from the financially distressed Bank of Taiwan. This aggressive action was widely seen as a primary cause for the collapse of both the Bank of Taiwan and Suzuki Shoten, contributing significantly to the ensuing financial panic across Japan. Ikeda was severely criticized for prioritizing Mitsui's interests over the stability of the broader financial system, with many blaming his actions for exacerbating the crisis.

4.2. Dollar Buying Incident and Public Criticism

Another major controversy that marred Ikeda's reputation was the "dollar buying incident" of 1931. As the Great Depression spread from Germany to Great Britain, the United Kingdom abandoned the gold standard, causing its collapse internationally. Anticipating that Japan would soon follow suit and prohibit gold exports, Ikeda instructed Mitsui to engage in speculative dollar buying through the Yokohama Specie Bank. This move was intended to protect Mitsui's assets and capitalize on the expected devaluation of the yen. However, the then-Finance Minister, Inoue Junnosuke, countered by raising the official discount rate and implementing financial tightening measures, which further aggravated the domestic economic downturn.

Mitsui, and Ikeda personally, became the target of intense public outrage, accused of profiting from the nation's economic hardship. Ikeda defended Mitsui's actions, stating that the company had been forced to convert its 80.00 M JPY worth of gold held in London into dollars after being denied permission by the British government to repatriate the gold to Japan, and that the amount involved was only 43.24 M JPY. He further argued, based on the principles of capitalism, that there was nothing wrong with buying dollars while Japan still permitted gold exports. However, the public, suffering from severe economic hardship, perceived his defense as "the arrogance of the rich" and reacted with fury, especially as the actual scale of Mitsui's speculative activities was far greater than his explanation. This incident led to Ikeda, along with Mitsui's managing director Dan Takuma, being targeted for assassination by the right-wing extremist group Blood Oath League (血盟団KetsumeidanJapanese). Although Ikeda survived, Dan Takuma was tragically assassinated in 1932.

5. Public Service and Political Career

Ikeda Shigeaki transitioned from a prominent business career to significant roles in government and public institutions, where he influenced Japan's economic and political direction during a period of escalating militarism.

5.1. Governor of the Bank of Japan

Upon his retirement from Mitsui in 1937, Ikeda accepted the prestigious position of the 14th Governor of the Bank of Japan, succeeding Eigo Fukai. He assumed this role on February 9, 1937, but his tenure was relatively brief, lasting until July 27, 1937, when he stepped down to take on other public service responsibilities, and was succeeded by Toyotarō Yūki. During his time as governor, he was responsible for managing Japan's monetary policy amidst growing economic challenges and increasing military influence.

5.2. Minister of Finance and Minister of Commerce and Industry

On October 14, 1937, Ikeda was appointed as a Cabinet councilor by Prime Minister Fumimaro Konoe. His influence grew further when, from May 26, 1938, to January 5, 1939, he concurrently served as both the 38th Minister of Finance (succeeding Okinori Kaya and followed by Sōtarō Ishiwata) and the 16th Minister of Commerce and Industry (succeeding Shinji Yoshino and followed by Yoshiaki Hatta) in the First Konoe Cabinet. In these crucial ministerial roles, Ikeda, alongside Foreign Minister Ugaki Kazushige's diplomatic policies, played a leading role in guiding the Konoe New Order Movement (近衛新体制運動Konoe Shin Taisei UndōJapanese), which aimed to restructure Japan's political and economic systems. He often found himself in conflict with the increasingly dominant Imperial Japanese Army, particularly over the implementation of the National Mobilization Law, where he attempted to counter the military's arbitrary actions with rational economic arguments, though ultimately without success. Due to these clashes and the growing military influence, Ikeda resigned from the cabinet along with Konoe in January 1939.

5.3. Cabinet Councilor and Advisory Roles

Even after his ministerial posts, Ikeda continued to hold significant advisory positions within the government. After the collapse of the First Konoe Cabinet, he was retained as a Cabinet councilor under Prime Minister Hiranuma Kiichiro from January 20 to August 30, 1939. He also served as an advisor to the Ministry of Finance, chairman of the Central Price Control Committee, and was a founding committee member for major state-backed development companies like the North China Development Company and the Central China Promotion Company. He was again appointed Cabinet councilor under the Second Konoe Cabinet from July 22, 1940, until July 18, 1941, demonstrating his continued influence and expertise in economic policy during a period of intense national mobilization.

5.4. Privy Councillor

In 1941, Ikeda was appointed as a member of the Imperial Privy Council under the cabinet of Hideki Tojo. This was a prestigious advisory body to the Emperor on state affairs. However, due to his known pro-Anglo-American sentiments, which were increasingly at odds with the prevailing militaristic and anti-Western ideology, Ikeda found himself under the close surveillance of the Kempeitai (military police) after the Tojo cabinet came to power.

5.5. Consideration for Prime Minister and Political Opposition

Ikeda Shigeaki was repeatedly considered as a potential candidate for Prime Minister during a turbulent political period, but his appointment was consistently thwarted by strong opposition from the Imperial Japanese Army. His name was first floated as a possible successor to Prime Minister Konoe. However, the Army, with whom Ikeda had frequently clashed over financial matters and their expansionist policies, strongly opposed his candidacy.

Later, after the collapse of the Hiranuma Cabinet, Genrō (elder statesman) Saionji Kinmochi considered Ikeda as the next prime minister. However, Konoe expressed reservations, believing that Ikeda would not be able to control the Army. Consequently, the Army's preferred candidate, Abe Nobuyuki, was appointed instead. Ikeda was again considered a potential premier after Abe's resignation, but once more, the Army's opposition prevented his selection, highlighting the significant power wielded by the military in pre-war Japanese politics and their distrust of Ikeda's pragmatic and less hawkish views.

6. Ideology and Foreign Relations

Ikeda Shigeaki's ideology was characterized by a pragmatic and liberal approach to economics and international relations, often placing him in opposition to the rising tide of Japanese militarism and ultranationalism.

6.1. Stance on Anglo-American Relations

Ikeda held a distinct pro-Anglo-American stance, advocating for cooperative relations with Great Britain and the United States. This perspective sharply contrasted with the prevailing nationalist and anti-Western sentiments, particularly those championed by figures like Fumimaro Konoe, who inherited his father Konoe Atsumaro's continental expansionist views and anti-Western sentiments. Ikeda's views were rooted in his background as a financial magnate from the Yonezawa domain and his exposure to Western economic principles during his studies abroad. He believed that maintaining strong economic and diplomatic ties with the Anglo-American powers was essential for Japan's prosperity and stability, a rational approach that often put him at odds with the military's aggressive foreign policy.

6.2. Involvement in the Fugu Plan

On December 5, 1938, Ikeda participated in the Five Ministers' Conference, a secret meeting of Japan's highest officials convened to discuss the government's position on Jewry. While Foreign Minister Hachiro Arita and others expressed opposition to formal involvement with Jewish people, influenced by anti-Semitic conspiracy theories such as the Protocols of the Elders of Zion and Nazi ideology, Ikeda, along with Army Minister Seishiro Itagaki, presented a contrasting view. They argued that a population of Jewish people could be a significant asset to Japan, capable of attracting foreign capital and improving international opinion towards Japan. This perspective, which highlighted the potential economic and diplomatic benefits of accepting Jewish refugees, was a crucial step in the development of the "Fugu Plan". This plan aimed to bring several thousand Jewish refugees from Nazi-controlled Europe to the Empire of Japan. Ikeda's involvement in this initiative underscores a humanitarian and pragmatic approach to a global crisis, reflecting a concern for human rights and a willingness to engage with international issues from a less ideologically rigid standpoint than many of his contemporaries.

6.3. Opposition to the Pacific War

Ikeda Shigeaki was a vocal opponent of Japan's entry into the Pacific War with the United States. His opposition was primarily based on pragmatic economic and diplomatic reasoning, as he understood the severe limitations of Japan's resources and the overwhelming industrial might of the Western powers. He frequently clashed with influential militarists, most notably Hideki Tojo, who became Prime Minister. Tojo, attempting to sway Ikeda, even offered to transfer Ikeda's third son, Toyo, who had been conscripted, to a safe posting in Tokyo. However, Ikeda immediately and firmly refused this offer, demonstrating his unwavering principles and commitment to fairness, even at personal cost. His son, Toyo, subsequently served as a common soldier in the Central China front, where he tragically succumbed to malnutrition and malaria, never reuniting with his family. Ikeda's steadfast opposition to the war, despite immense pressure and personal sacrifice, highlights his foresight and courage in challenging the prevailing militaristic tide.

7. Post-War Period and Retirement

The end of World War II brought a dramatic shift in Ikeda Shigeaki's life, leading to his arrest, disqualification from public office, and a complex role in Japan's post-war reconstruction.

7.1. Arrest and Release as a War Crimes Suspect

In December 1945, following Japan's surrender, Ikeda was arrested on the orders of the Supreme Commander of the Allied Powers (SCAP), the United States occupation authorities. He was among 59 individuals on the "third arrest list" and was detained in Sugamo Prison as a suspect on charges of Class A war crimes, which included crimes against peace. However, after approximately five months of detention, he was released in May 1946 without any formal charges being filed against him. This release suggested that the occupation authorities did not find sufficient evidence to prosecute him for direct responsibility in initiating or directing the war.

7.2. Disqualification from Public Office and Retirement

Despite his release, like all members of the wartime Japanese government, Ikeda was barred from holding any public office under the Allied Occupation's purge directives. This effectively ended his long and influential career in public service. Following his disqualification, Ikeda withdrew from public life and retired to his summer home in Oiso, Kanagawa Prefecture, where he lived a quiet, reclusive life.

7.3. Cooperation with GHQ and Zaibatsu Dissolution

Despite his forced retirement and the personal cost, Ikeda actively cooperated with the American occupation officials (GHQ) in the dissolution of the zaibatsu. This cooperation was a strategic decision on his part, as he believed that proactively assisting GHQ would be beneficial for the future re-establishment and preservation of the Mitsui corporate group, rather than a move against the Mitsui family itself. However, this stance earned him considerable enmity and deep resentment from many of his former colleagues within the Mitsui group and the Mitsui family, who viewed his actions as "ungrateful" and "cold-hearted" given his long history with the conglomerate and his prior role in removing the family from direct management. This episode also implicitly demonstrated that, despite introducing a formal retirement system, Ikeda continued to exert significant influence over the zaibatsu's affairs.

7.4. Relationship with Prime Minister Yoshida

Even in his retirement, Ikeda Shigeaki maintained a degree of influence and was sought out for his expertise. His close neighbor in Oiso was Shigeru Yoshida, who would become Prime Minister of Japan. Yoshida frequently consulted with Ikeda on matters of finance and personnel, valuing his insights and experience. Notably, Ikeda recommended his former secretary, Izumiyama Sanroku, to Yoshida for the position of Finance Minister, showcasing his continued, albeit informal, role in shaping post-war Japanese leadership and economic policy.

8. Family and Personal Life

Ikeda Shigeaki's personal life reflected both his prominent family background and distinctive personal traits, which contributed to his public persona.

8.1. Family and Relatives

Ikeda Shigeaki was married to Tsya, the eldest daughter of Nakamigawa Hirojiro, a powerful figure within the Mitsui Zaibatsu. Their eldest daughter, Toshiko, married Iwasaki Takaya. His eldest son, Seikō, became a director at Japan Horticulture Co. His second son, Ikeda Kiyoshi, achieved renown as an English scholar, critic, and Keio University emeritus professor. Ikeda's family connections extended further through his sisters, whose husbands included Kato Takeo, a former president of Mitsubishi Bank, and Usami Katsuo, a former governor of Tokyo Prefecture. His nephews included Usami Makoto, a former Governor of the Bank of Japan, and Usami Takeshi, a former Director-General of the Imperial Household Agency. His younger brother, Ikeda Kohei, was a Navy lieutenant who tragically died in the Battle of Tsushima.

8.2. Personal Traits and Anecdotes

Ikeda was widely known for his reserved and quiet demeanor. While some attributed this to his father's strict upbringing, Ikeda himself reportedly explained that he remained silent to avoid revealing his regional dialect. An anecdote from his time at Keio University illustrates his independent and disciplined nature: when students organized a boycott of the cafeteria due to poor food quality, Ikeda refused to participate, reportedly expressing dismay that students, who were there to study, would strike over food. His strong loyalty to Keio University was also evident in his famous dislike of Waseda University. This animosity was so pronounced that he was a staunch opponent on the Keio University Board of Councilors, contributing to the suspension of the Sokeisen (Keio-Waseda baseball matches) from 1906 until their resumption in 1925. Ikeda also articulated his personal philosophy in a work titled "My Bamboo Shoot Philosophy" (私のたけのこ哲学Watashi no Takenoko TetsugakuJapanese).

9. Death and Legacy

Ikeda Shigeaki's passing marked the end of an era, and his legacy continues to be assessed for his profound impact on Japan's economic and political trajectory.

9.1. Death and Honors

Ikeda Shigeaki died on October 9, 1950, at his home in Oiso, Kanagawa Prefecture, at the age of 83, due to complications arising from intestinal ulcers. Following his death, he received imperial condolences in the form of a saisokuryō (imperial offering for a deceased person). However, he had previously requested that an imperial envoy not be dispatched, reflecting his humble and private nature even in death. His grave is located at Gokoku-ji temple in Bunkyo-ku, Tokyo.

He was posthumously honored with several distinctions during his lifetime:

- Court Rank:**

- Junior Fifth Rank: November 10, 1928

- Junior Third Rank: June 1, 1938

- Senior Third Rank: April 15, 1944

- Orders and Medals:**

- Commemorative Medal for the 2600th Imperial Anniversary: August 15, 1940

- Order of the Sacred Treasure, Second Class: March 7, 1944

9.2. Historical Assessment and Impact

Ikeda Shigeaki's historical assessment is complex, balancing his significant contributions to Japan's economic modernization with the controversies he faced and his later principled opposition to militarism. As a key figure in the Mitsui Zaibatsu, he was instrumental in transforming Mitsui Bank into a modern stock company and implementing progressive management reforms, including the introduction of a retirement system. His leadership helped solidify Mitsui's position as a dominant force in the Japanese economy.

However, his actions during the Showa Financial Crisis and the "dollar buying incident" drew severe public criticism, highlighting the social tensions between corporate interests and the struggles of ordinary citizens during times of economic hardship. These events contributed to a public perception of zaibatsu arrogance and even led to him being targeted for assassination, underscoring the deep societal discontent of the era.

From a perspective emphasizing social progress and human rights, Ikeda's involvement in the Fugu Plan stands out as a notable humanitarian effort, demonstrating a willingness to offer refuge to Jewish people amidst global persecution, a stance that diverged from the prevailing anti-Semitic views in some circles. His strong and consistent opposition to Japan's entry into the Pacific War, based on rational economic and diplomatic considerations, further distinguishes him as a voice of reason against the tide of militarism. His refusal to accept special treatment for his son's conscription, leading to his son's death in the war, serves as a powerful testament to his integrity and principled stand against the military's overreach.

In the post-war period, his pragmatic cooperation with the GHQ in the dissolution of the zaibatsu, while earning him the ire of his former colleagues, can be viewed as a forward-looking decision that facilitated Japan's economic reconstruction and integration into the post-war international order. His continued, albeit informal, advisory role to Prime Minister Shigeru Yoshida further illustrates his enduring influence on Japan's financial and political recovery. Overall, Ikeda Shigeaki is remembered as a shrewd financial leader who navigated Japan through periods of immense economic and political upheaval, leaving a mixed but ultimately significant legacy that includes both the pursuit of corporate power and a principled stand for peace and human rights.