1. Life

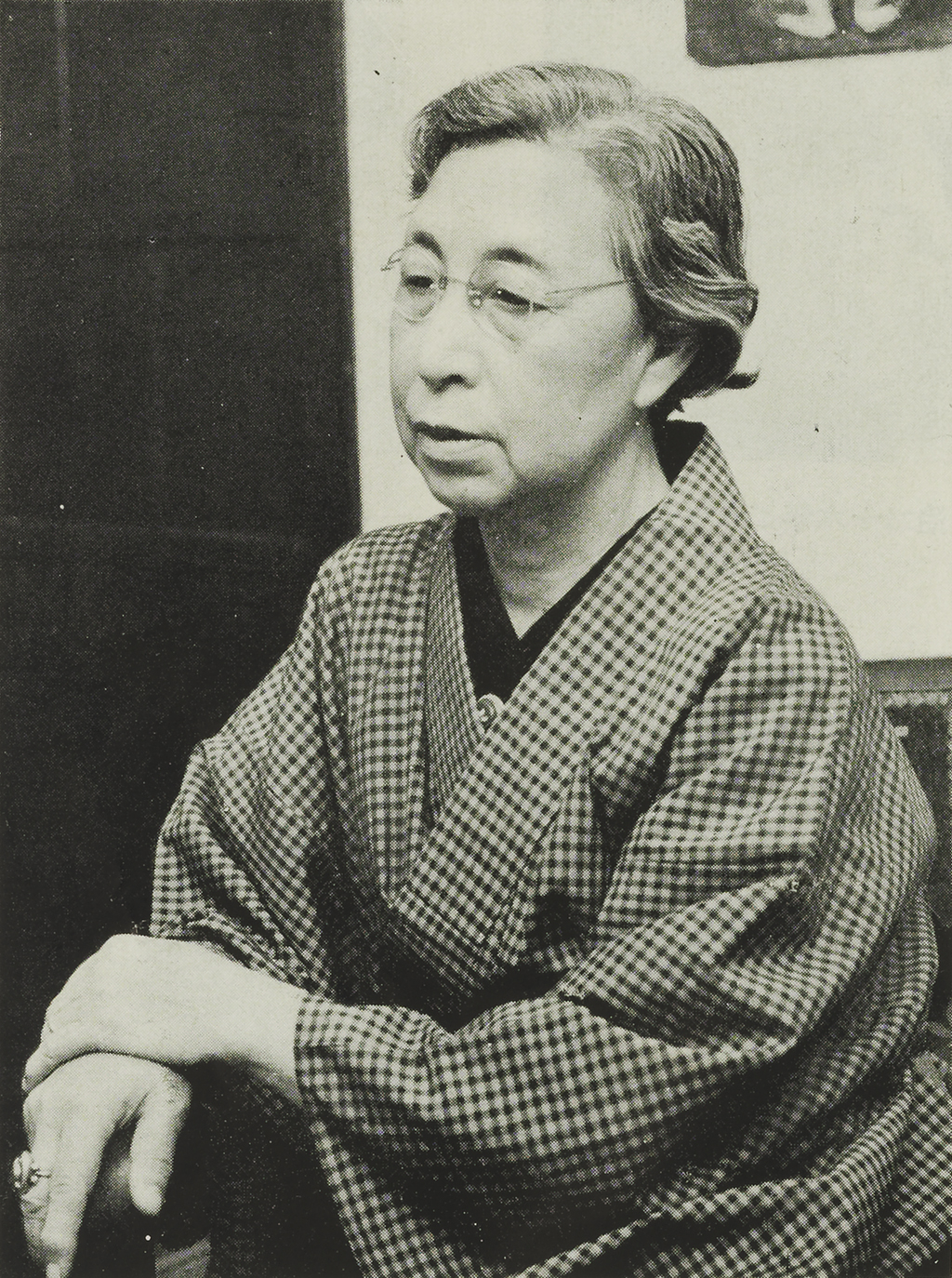

Hiratsuka Raichō's life was marked by intellectual curiosity, personal rebellion, and unwavering dedication to social reform and women's rights, from her privileged upbringing to her post-war activism.

1.1. Birth and Early Life

Hiratsuka Raichō was born Hiratsuka Haru on February 10, 1886, in Kōjimachi-ku, Tokyo (present-day Gobanchō, Chiyoda-ku), into a prosperous family. She was the youngest of three daughters. Her father, Hiratsuka Teijirō, was a high-ranking civil servant who worked for the Board of Audit of Japan and later lectured at First Higher School. Her mother, Tsuya, came from the Iijima family, who served as physicians to the Tayasu Tokugawa family, one of the Gosankyo (three collateral branches of the Tokugawa clan). Her parents were highly dedicated to education. From 1887, her father spent a year and a half observing Europe and America, influencing her early upbringing in a liberal, Western-oriented environment. However, around 1892, her father shifted to a more nationalistic approach to family education, coinciding with the end of the Rokumeikan era.

In 1894, her family moved to Komagome Akebono-chō in Hongō-ku (present-day Honkomagome, Bunkyō-ku). She transferred to Seishi Elementary School and, in 1898, entered the Tokyo Women's Higher Normal School Affiliated High School (present-day Ochanomizu University Senior High School), a model school for nationalistic education at the time. Dissatisfied with the emphasis on the "Good Wife, Wise Mother" ideology, she formed a "Pirate Group" with classmates and boycotted ethics classes. Hiratsuka was born with weak vocal cords, making her voice quiet and soft. Her quiet demeanor and reserved nature, as observed by her grandchildren, contrasted sharply with her public image as a fierce activist.

1.2. University Life and Intellectual Influences

In 1903, Hiratsuka enrolled in the Department of Home Economics at Japan Women's University (日本女子大学Japanese, Nihon Joshi Daigaku), persuading her father who believed women did not need education beyond high school. She was drawn to the university's educational philosophy, which aimed to educate women "as persons, as women, and as citizens." However, with the outbreak of the Russo-Japanese War the following year, the university's curriculum became increasingly nationalistic, leading to her disillusionment.

During this period, she immersed herself in religious and philosophical texts to understand her inner conflicts. In 1905, she discovered Zen Buddhism and began training at the Ryōbō-an (両忘庵Japanese) Zen dojo in Nippori (present-day Ningen Zen Takuboku Dōjō). She achieved enlightenment through kōan practice and received the Buddhist name Ekun Zenko (慧薫禅子). After graduating from Japan Women's University in 1906, she continued her Zen practice while studying Chinese classics at Nishō Gakusha (present-day Nishogakusha University) and English at Joshi Eigakujuku (present-day Tsuda University). In 1907, she further attended Seibi Higher English Girls' School (成美高等英語女学校Japanese).

It was at Seibi Higher English Girls' School that she first encountered literature through Goethe's *The Sorrows of Young Werther*, which ignited her passion for literature. She became a student of Ikuta Chōkō, a new teacher from Tokyo Imperial University, and joined the "Keishū Bungakkai" (閨秀文学会Japanese), an extracurricular literary course organized by Ikuta and Morita Sōhei. Her debut novel, "The Last Day of Love," written at Ikuta's suggestion, was highly praised by Morita, leading to their romantic involvement. Hiratsuka was also deeply influenced by contemporary European philosophy, the Swedish feminist writer Ellen Key-whose works she translated into Japanese-and the individualistic heroine of Henrik Ibsen's 1879 play *A Doll's House*. During her time at Japan Women's University, she also explored the works of Baruch Spinoza, Meister Eckhart, and G. W. F. Hegel.

1.3. The Seitō Era and "In the beginning, woman was the sun"

In 1908, at the age of 22, Hiratsuka attempted a double suicide with Morita Sōhei, her teacher and a disciple of novelist Natsume Sōseki, in the snowy mountains near Otōtōge Pass in Nasushiobara, Tochigi Prefecture. The pair were rescued by police, but the incident, known as the Shiobara Incident or Baien Incident (named after Morita's novel *Baien* based on the event), was widely sensationalized by newspapers as a scandal involving a highly educated couple. This brought her widespread notoriety and public criticism, leading to her name being removed from Japan Women's University's alumni list (though it was reinstated in 1992).

Following the Shiobara Incident, Hiratsuka, strongly encouraged by Ikuta Chōkō, began the production of *Seitō* (青鞜Japanese, literally "Bluestocking"), Japan's first literary magazine by and for women. The funding came from her mother's savings, originally intended for Hiratsuka's marriage. She established the Seitō-sha publishing house, with her classmates and peers contributing to its planning, while she focused on production. The first issue, published in September 1911, featured a cover illustration by Takamura Chieko (then Naganuma Chie) and a poem titled "Sozorogoto" by Yosano Akiko, famous for the line "The day the mountains move will come." Hiratsuka penned the inaugural essay, "In the beginning, woman was the sun" (「元始、女性は太陽であった」Japanese), a reference to the Shinto sun goddess Amaterasu and a powerful call for women's spiritual independence, which she believed they had lost.

Adopting the pen name Raichō ("Thunderbird"), inspired by the ptarmigan, a bird she admired during her recovery in Nagano Prefecture after the Shiobara incident, she advocated for a women's spiritual revolution. The magazine garnered extreme reactions, with an outpouring of support from female readers and intense animosity from male readers and the press, who mocked Seitō-sha and even threw stones at Hiratsuka's home. Despite this, Raichō remained defiant, once writing in the editor's note that she "drank the most beer," a provocative statement.

The journal's focus gradually shifted from literature to women's issues, including candid discussions of female sexuality, chastity, and abortion. Contributors included renowned poet and women's rights proponent Yosano Akiko. In April 1913, her essay "To the Women of the World" (「世の婦人たちに」Japanese) fiercely rejected the conventional role of women as ryōsai kenbo (良妻賢母Japanese): "I wonder how many women have, for the sake of financial security in their lives, entered into loveless marriages to become one man's lifelong servant and prostitute." This nonconformity led to public labeling of the Seitō members as "new women."

The Seitō-sha also published other works, including Okamoto Kanoko's poetry collection *Karoki Netami* in late 1912 and *Seitō Shōsetsu-shū* in March 1913. Hiratsuka's debut collection of essays, *Marumado yori* (円窓よりJapanese, "The View from the Round Window"), published in May 1913, was banned immediately after its release for "destroying the family system and corrupting public morals." It was reissued in June 1913 under the title *Tozashi Aru Mado Nite* (※<外字。とざし>ある窓にてJapanese, "From a Closed Window").

The magazine's radical content and the nonconformist behavior of its members, such as the "Five-color sake incident" (where Otaka Beniyoshi ordered colorful cocktails at a bar) and the "Yoshiwara brothel visit" (where Raichō, Otaka Beniyoshi, and Nakano Hatsuko visited a brothel with Otaka's uncle, the painter Otaka Chikuha), along with rumors of a homosexual relationship between Raichō and Beniyoshi, further fueled public outrage. In February 1913, an article by Fukuda Hideko in *Seitō* stating, "When communism is achieved, love and marriage will naturally become free," led to the issue being banned for "harming public order," causing Raichō's father to demand she leave home and prepare for independence.

The journal ceased publication in 1915, but not before establishing Hiratsuka as a leading figure in Japan's women's movement.

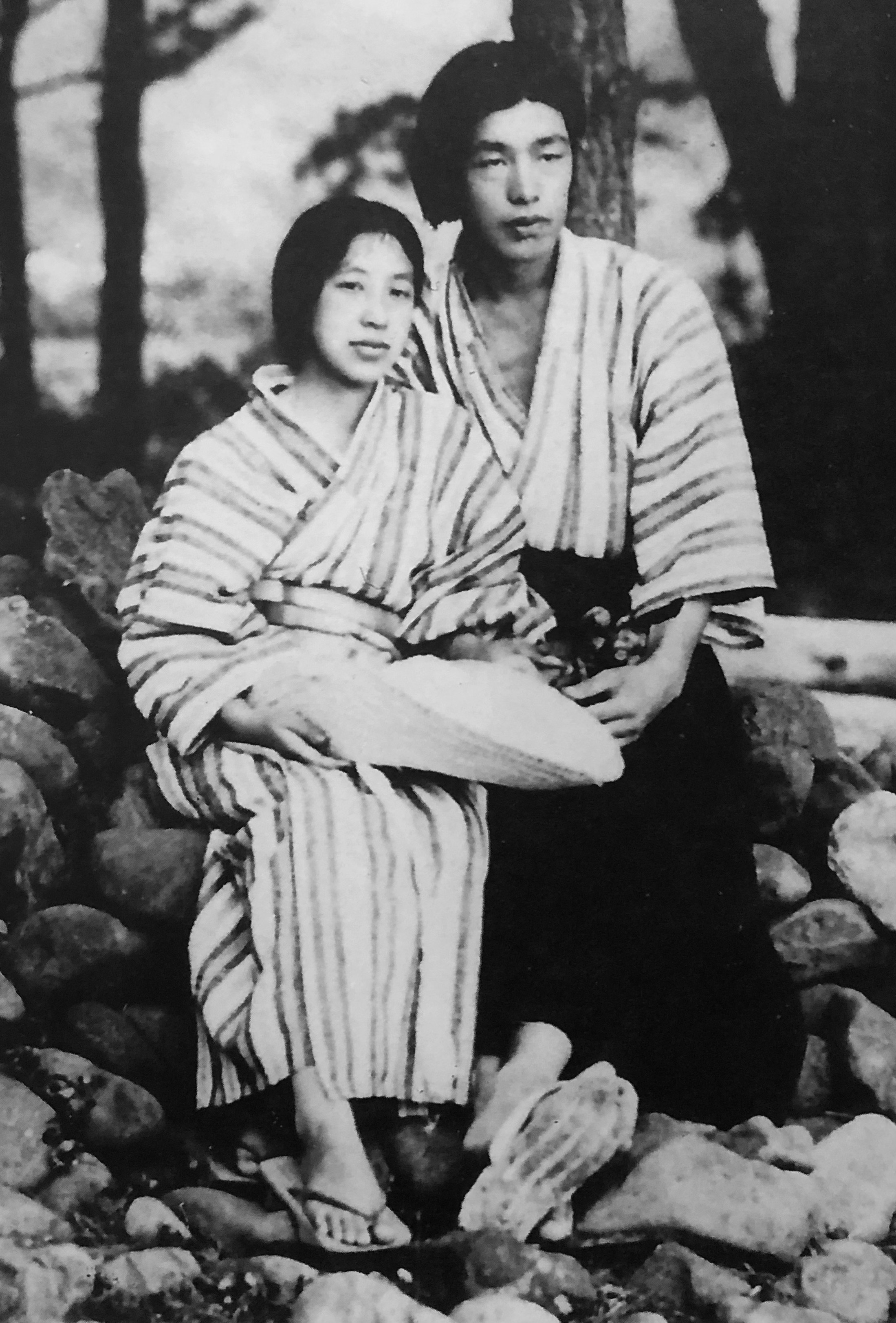

1.4. Personal Relationships and Social Controversies

In the summer of 1912, at the age of 26, Hiratsuka met Okumura Hiroshi (奥村博史Japanese), a painter five years her junior, in Chigasaki. After a period of public controversy surrounding their relationship, she began living with him in an unconventional common-law marriage arrangement, rejecting the traditional marriage system and the "house" system. She became the head of her own branch family register and registered their two children as illegitimate. Okumura, a talented artist and stage performer, suffered from poor health (contracting tuberculosis shortly after their cohabitation) and struggled to sell his paintings, making Raichō the primary breadwinner through her writing. Their financial struggles heavily influenced her later advocacy for state support for mothers. The anecdote about the origin of the term "tsubame" (swallow) for a younger male lover stems from a letter Okumura wrote to Raichō when he decided to leave her, which she published in *Seitō*: "A swallow flew into a place where quiet water birds were playing peacefully and disturbed the peace. The young swallow flies away for the peace of the pond."

In 1915, due to the difficulty of balancing her family life with Okumura (who was ill) and her work for *Seitō*, she handed over the editorship of the magazine to Itō Noe. Under Noe's leadership, *Seitō* became more focused on anarchist discourse but ceased publication a year later after the Hikagejaya Incident, where Kamichika Ichiko stabbed Ōsugi Sakae, with whom Noe had begun a relationship. Hiratsuka and Okumura eventually formalized their marriage in 1941, primarily to ensure their son would not face disadvantages during his military service due to his illegitimate status.

In a 1917 essay titled "On the Permissibility of Contraception," Hiratsuka expressed a positive view of eugenics, advocating for birth control.

1.5. Feminist Activism

After relinquishing editorship of *Seitō*, Hiratsuka focused on caring for Okumura and raising their children. However, in 1918, a debate erupted when Yosano Akiko published "The Complete Independence of Women" in *Fujin Kōron* (婦人公論Japanese), arguing that demanding state protection for motherhood was a form of dependency. Hiratsuka countered in the same magazine with "Is the Demand for Maternity Protection a Form of Dependency?", asserting that women's freedom and independence could only be meaningful with freedom in love and the establishment of motherhood. This sparked the "Maternity Protection Controversy" (母性保護論争Japanese, Bosei-hogo ronsō), which was joined by Yamakawa Kikue (arguing true maternity protection was only possible in socialist countries) and Yamada Waka, becoming a major social phenomenon. Hiratsuka, influenced by Ellen Key's emphasis on motherhood, argued that complete financial independence was impractical for women at the time and that government financial assistance for maternity protection was necessary for women to establish their national and social existence, especially given the difficult conditions of female workers.

In 1919, after inspecting textile factories in Nagoya and being deeply affected by the harsh conditions of female laborers, Hiratsuka solidified her resolve for political action. On November 24, 1919, she announced the establishment of the New Women's Association (新婦人協会Japanese, Shin-fujin kyokai) with the cooperation of fellow women's rights activists Ichikawa Fusae and Oku Mumeo. This was Japan's first women's organization dedicated to securing women's political and social freedoms, demanding women's suffrage and maternity protection. The association's organ, *Josei Dōmei* ("Women's Alliance"), also featured Hiratsuka's inaugural address.

The New Women's Association members, including Hiratsuka, were actively involved in various campaigns. A photograph from 1920 shows some of the key figures.

They submitted petitions for the revision of the House of Representatives Election Law, the amendment of Article 5 of the Police Security Regulations, and marriage restrictions and divorce claims against men with venereal disease. A meeting photograph from July 18, 1920, captures some of the prominent figures involved in these efforts.

This campaign was successful, and Article 5 was overturned in 1922, a significant victory. However, women's suffrage remained elusive in Japan at this time. The campaign to ban men with venereal disease from marrying, however, was unsuccessful and remains a controversial aspect of Hiratsuka's career, as it aligned her with the eugenics movement, arguing that the spread of venereal disease negatively impacted the "Japanese race."

In 1921, due to overwork and conflicts with Ichikawa Fusae, Hiratsuka withdrew from the association's management. Socialist women, including Itō Noe, Sakai Magara, and Yamakawa Kikue, formed the Sekirankai and criticized the New Women's Association and Hiratsuka. After Hiratsuka left and Ichikawa traveled to the United States, the New Women's Association continued its activities under the leadership of Sakamoto Makoto and Oku Mumeo, successfully amending Article 5 of the Police Security Regulations in 1922. However, its activities subsequently stagnated, and it disbanded in late 1923. Hiratsuka then largely focused on her writing career.

In the 1930s, during the Great Depression, Hiratsuka became involved in the consumer cooperative movement, believing it to be the most effective means of achieving widespread social reform. She also participated in the anarchist-leaning magazine *Fujin Sensen* ("Women's Front") led by Takamure Itsue. The following years saw her somewhat withdraw from the public eye, burdened by debt and her partner's health issues, though she continued to write and lecture.

1.6. Post-War Activities and Peace Movement

In the post-World War II era, Hiratsuka re-emerged as a prominent public figure through her involvement in the peace movement. In June 1950, the day after the outbreak of the Korean War, she, along with writer and activist Nogami Yaeko and three other members of the Japan Women's Movement (婦人運動家Japanese), traveled to the United States. There, they presented US Secretary of State Dean Acheson with a request for a system that would allow Japan to remain neutral and pacifist. In December 1951, she formed the "Committee for Opposition to Rearmament by Women" to protest the peace treaty with Japan and the Japan-US Security Treaty.

On April 5, 1953, she established the Japan Women's Organizations' Federation (日本婦人団体連合会Japanese, Nihon Fujin Dantai Rengōkai) and became its first chairperson. In December of the same year, she was appointed Vice President of the Women's International Democratic Federation. In 1955, she participated in the formation of the World Peace Appeal Seven Committee (世界平和アピール七人委員会Japanese) and became a member. In 1960, she co-signed a statement advocating for complete disarmament and the abolition of the Japan-US Security Treaty.

On October 19, 1962, the New Japan Women's Association (新日本婦人の会Japanese, Shin Nihon Fujin no Kai) was formed at the initiative of Hiratsuka, Iwasaki Chihiro, Nogami Yaeko, Hani Setsuko, Kishi Teruko, Kuwazawa Yoko, Kushida Fuki, Fukao Sumako, Tsuboi Sakae, and 23 other women. This organization remains active today.

Hiratsuka continued to advocate for women's rights and peace in the post-war era, actively campaigning against the Vietnam War. In 1966, she formed the "Vietnam Dialogue Group" (ベトナム話し合いの会Japanese), and in July 1970, she established the "Vietnam Mother and Child Health Center" (ベトナム母と子保健センターJapanese).

On February 18, 1964, her husband, Okumura Hiroshi, died at the Kanto Central Hospital in Setagaya-ku, Tokyo, from acute myeloid leukemia. Hiratsuka Raichō passed away on May 24, 1971, at Yoyogi Hospital in Sendagaya, Tokyo, at the age of 85, after suffering from gallbladder and bile duct cancer since 1970. Even during her hospitalization, she continued dictating her autobiography. Her Buddhist name is Meiō no Mikoto (明媼之命). The anniversary of her death, May 24, is known as "Raichō-ki" (らいてう忌Japanese).

2. Thought and Philosophy

Hiratsuka Raichō's thought evolved from a quest for individual spiritual liberation to a comprehensive vision of women's rights and social reform. Her philosophy was deeply influenced by a blend of Eastern and Western intellectual traditions.

Her early intellectual development was shaped by European philosophy, particularly the individualism found in the works of Ellen Key and Henrik Ibsen. Key's arguments for the priority of motherhood resonated with Hiratsuka, influencing her later advocacy for state support for mothers. Her engagement with Zen Buddhism provided a spiritual foundation, leading her to believe in women's innate "spiritual independence," which she famously articulated in "In the beginning, woman was the sun." This manifesto was not merely a literary statement but a philosophical call for women to reclaim their inherent power and break free from societal constraints.

She critically analyzed traditional gender roles, particularly the "Good Wife, Wise Mother" ideal, advocating for women's right to self-determination in marriage, sexuality, and motherhood. Her unconventional personal life, including her common-law marriage and decision to raise her children as illegitimate, was a practical manifestation of her rejection of the restrictive "house" system and traditional marriage institutions.

In the Maternity Protection Controversy, her stance reflected a pragmatic view that complete financial independence for women was not always feasible given the societal conditions, thus necessitating state intervention to protect motherhood and ensure women's social existence. While her controversial support for eugenics in the context of venereal disease prevention is a complex aspect of her thought, it stemmed from a concern for the health of the "Japanese race," reflecting the prevalent scientific and social ideas of her time.

Later in her life, her focus broadened to encompass broader social issues. Her involvement in the cooperative movement indicated a belief in collective action for social reform. After World War II, her dedication to the peace movement became central, advocating for Japan's neutrality and pacifism. This reflected a deep commitment to human rights and a critical stance against militarism, aligning her with progressive movements for global peace. Throughout her life, Hiratsuka maintained a strong sense of individual agency, famously declaring, "Every woman is a genius in her own right," a testament to her belief in the inherent potential and autonomy of women.

3. Writings and Publications

Hiratsuka Raichō was a prolific writer, contributing numerous original works, essays, and translations that were central to the feminist and social reform movements in Japan.

3.1. Original Works

- Marumado yori (『円窓より』Japanese, The View from the Round Window, 1913)

- Tozashi Aru Mado Nite (『※<外字。とざし>ある窓にて』Japanese, From a Closed Window, 1913)

- Gendai to Fujin no Seikatsu (『現代と婦人の生活』Japanese, Modern Times and Women's Lives, 1914)

- Raichō Daisan Bunshū Gendai no Danjo e (『らいてう第三文集 現代の男女へ』Japanese, Raichō's Third Collection: To Modern Men and Women, 1917)

- Fujin to Kodomo no Kenri (『婦人と子供の権利』Japanese, Women's and Children's Rights, 1919)

- Josei no Kotoba (『女性の言葉』Japanese, Words of Women, 1926)

- Raichō Zuihitsu-shū Kumo Kusa Hito (『らいてう随筆集 雲・草・人』Japanese, Raichō's Essay Collection: Clouds, Grass, People, 1933)

- Haha no Kotoba (『母の言葉』Japanese, Mother's Words, 1937)

- Watakushi no aruita michi (『私の歩いた道』Japanese, The Road I Walked, 1955)

3.2. Autobiography

- Genshi, josei wa taiyō de atta (『元始、女性は太陽であった』Japanese, In The Beginning Woman Was The Sun), Ohtsuki Shoten, 1971-1973 (4 volumes)

- Volume 1 (1971)

- Volume 2 (1971)

- Volume 3 (1972)

- Volume 4 (1973)

- Revised edition in Ohtsuki Shoten's Kokumin Bunko series (1992, 4 volumes)

3.4. Edited Works

- Warera Haha Nareba Heiwa o Inoru Haha-tachi no Shuki (『われら母なれば 平和を祈る母たちの手記』Japanese, Because We Are Mothers: Memoirs of Mothers Praying for Peace), supervised with Kushida Fuki, Seidō-sha, 1951.

3.5. Translations

- Ellen Key, The Renaissance of Motherhood (『母性の復興』Japanese, Bosei no fukkō, 1919)

- Ellen Key, Love and Marriage (『愛と結婚』Japanese, Ai to kekkon)

- John Stuart Mill, The Subjection of Women (『婦人の隷属』Japanese, Fujin no Reizoku, 1929)

3.6. Collected Works

- Hiratsuka Raichō Chosakushū (『平塚らいてう著作集』Japanese, Collected Works of Hiratsuka Raichō), Ohtsuki Shoten, 1983-1984 (8 volumes including a supplementary volume)

- Volume 1: Seitō (青鞜Japanese)

- Volume 2: Bosei no Shuchō ni tsuite (母性の主張についてJapanese, On the Assertion of Motherhood)

- Volume 3: Shakai Kaizō ni taisuru Fujin no Shimei (社会改造に対する婦人の使命Japanese, Women's Mission for Social Reform)

- Volume 4: Mushiro Sei o Reihai seyo (むしろ性を礼拝せよJapanese, Rather, Worship Sexuality)

- Volume 5: Fujin Sensen ni Sanka shite (婦人戦線に参加してJapanese, Participating in the Women's Front)

- Volume 6: Musume ni Haha no Isan o Kataru (娘に母の遺産を語るJapanese, Telling My Daughter About My Mother's Legacy)

- Volume 7: Watakushi wa Eien ni Shitsubō shinai (私は永遠に失望しないJapanese, I Will Never Despair)

- Supplementary Volume: Photos, Letters, Chronology, Bibliography

- Hiratsuka Raichō Hyōronshū (『平塚らいてう評論集』Japanese, Collected Essays of Hiratsuka Raichō), edited by Kobayashi Tomie and Yoneda Sayoko, Iwanami Shoten, 1987.

4. Family

Hiratsuka Raichō's family life, though often unconventional by contemporary standards, played a significant role in her personal and public life.

Her father, Hiratsuka Teijirō, was a former samurai of the Kishū Domain who studied at the Tokyo School of Foreign Languages and became a secretary at the Sanjiin. In 1886, he moved to the Board of Audit and spent a year and a half observing Europe and America. He also taught German at the First Higher School.

Her husband, Okumura Hiroshi (奥村博史Japanese, 1889-1964), was a Western-style painter and stage artist born in Fujisawa, Kanagawa Prefecture. The Okumura family were former samurai of the Kaga Domain who later became pioneers in Yoichi, Hokkaido, building wealth through dry goods trading. Hiroshi moved to Tokyo at 18 and studied at Ōshita Tōjirō's Japan Watercolor Painting Institute. He met Raichō there and later participated in the Shingeki (New Theater) movement, appearing in performances such as Faust in 1913. He was also known as a ring maker, receiving an award in the crafts division of the Kokuga-kai in 1933 and becoming a member. He suffered from poor health, including tuberculosis, which led to his hospitalization in Nankoin. He later taught art at Seijo Gakuen from 1925, with students including Ōoka Shōhei, and was a member of Mushanokōji Saneatsu's Atarashiki Mura (New Village). He authored an autobiographical novel, *Meguriai* (Encounters, 1956). Raichō's grave was built after Hiroshi's death, and they are buried together.

Hiratsuka and Okumura had two children:

- Daughter, Akemi (曙生Japanese, 1915-1993): During her pregnancy with Akemi, Raichō was writing a serialized piece titled "Tōge" (Pass) about her double-suicide attempt with Morita Sōhei, but she had to pause due to morning sickness. Akemi was born while Okumura was hospitalized. She attended several elementary schools, including Takinogawa Kindergarten, Sakuyama Elementary School, Fujimae Elementary School, and Seijo Elementary School. Akemi married Tsukizoe Shōji, a sociologist and staff member at Ōmi Gakuen. She co-authored Boshi Zuihitsu (Mother and Child Essays) with Hiratsuka Raichō in 1948. She passed away from pneumonia complicated by aplastic anemia, attended by her daughters Mika and Mido.

- Son, Atsufumi (奥村敦史Japanese, 1917-2015): He became a professor of mechanical engineering at Waseda University. His works include *Zairyō Rikigaku* (Strength of Materials), *Mekanikusu Nyūmon* (Introduction to Mechanics), and *Watakushi wa Eien ni Shitsubō Shinai Shashin-shū Hiratsuka Raichō - Hito to Shōgai* (I Will Never Despair: Photo Collection of Hiratsuka Raichō - The Person and Her Life). He died at the age of 97 from old age.

Hiratsuka Raichō also had several grandchildren:

- Grandson, Okumura Naofumi (奥村直史Japanese, born 1945): Atsufumi's son. He graduated from Waseda University with a degree in psychology. He worked as a psychotherapist in hospitals and later became a part-time lecturer at Toyo Gakuen University. He served on the steering committee of the Japanese Association of Clinical Psychology from 1973 to 2007. He authored Hiratsuka Raichō: Mago ga Kataru Sugao (Hiratsuka Raichō: Her True Face as Told by Her Grandson, 2011) and Hiratsuka Raichō Sono Shisō to Mago kara Mita Sugao (Hiratsuka Raichō: Her Thought and Her True Face as Seen by Her Grandson, 2021). His observations revealed that, contrary to her public image, Raichō was small (around 57 in (145 cm) tall), quiet, and introverted.

- Granddaughter, Tsukizoe Mika (築添美可Japanese): Akemi's daughter. She worked as a nude dancer at Nichigeki Music Hall in the 1970s under the stage name Honō Mika (炎美可).

- Granddaughter, Tsukizoe Mido (築添美土Japanese): Akemi's daughter.

5. Legacy and Impact

Hiratsuka Raichō's legacy is profound and multifaceted, cementing her status as a foundational figure in Japanese feminism and a persistent advocate for social change and peace. She is primarily remembered for her leadership of the Seitō group, which, despite its relatively short existence, ignited a spiritual and intellectual revolution among Japanese women. Her declaration, "In the beginning, woman was the sun," remains an iconic rallying cry for women's spiritual independence and self-realization.

Her influence extended beyond Japan, notably impacting pioneering Korean feminist author Na Hye-sok (나혜석; 羅蕙錫Na Hye-sokKorean), who was a student in Tokyo during Seitō's heyday. Within Japan, her activism inspired figures like the anarchist and social critic Itō Noe, whose involvement with Seitō-sha generated considerable controversy but further amplified the movement's radical edge.

Hiratsuka's efforts were instrumental in achieving concrete legal reforms, most notably the overturning of Article 5 of the Police Security Regulations in 1922, which had long restricted women's political participation. Her advocacy for maternity protection, though controversial at times, highlighted crucial issues regarding women's economic and social rights within the family and society.

In the post-war era, her unwavering commitment to pacifism and neutrality, exemplified by her appeals to the United States government and her involvement in various peace organizations, solidified her role as a leader in Japan's peace movement. The New Japan Women's Association (新日本婦人の会Japanese), which she co-founded in 1963, continues to be an active force for women's rights and peace today, carrying forward her vision.

Her contributions have been recognized through various honors. In 2005, Japan Women's University established the "Hiratsuka Raichō Award" to commemorate the 100th anniversary of her graduation. On February 10, 2014, Google celebrated her 128th birthday with a Google Doodle, bringing her legacy to a global audience.

Hiratsuka Raichō's impact extends beyond specific achievements; she fostered a critical consciousness regarding gender roles and societal structures, paving the way for future generations of activists and thinkers. Her courage in challenging conventions, both personally and politically, continues to inspire those who strive for a more equitable and peaceful world.

6. Related Topics

- Feminism in Japan

- Good Wife, Wise Mother

- Ichikawa Fusae

- Itō Noe

- Japan Women's University

- Korean War

- Maternity Protection Controversy

- Na Hye-sok

- New Japan Women's Association

- New Women's Association

- Oku Mumeo

- Okumura Hiroshi

- Peace movement

- Seitō (magazine)

- Yamakawa Kikue

- Yosano Akiko