1. Overview

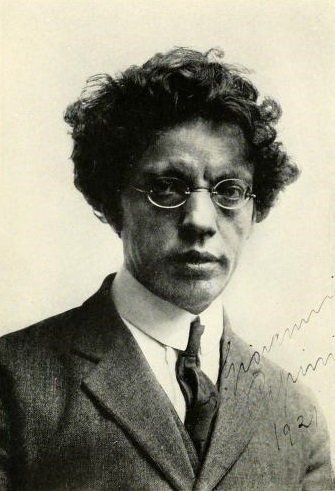

Giovanni Papini (Giovanni PapiniGiovanni PapiniItalian), born on January 9, 1881, and passing away on July 8, 1956, was an influential yet controversial Italian writer, journalist, essayist, novelist, short story writer, poet, literary critic, and philosopher. Active throughout the early and mid-20th century, he was a prominent figure in Italian intellectual and literary circles, known for his distinctive writing style and engagement in heated polemics. Papini's intellectual journey was marked by frequent and often abrupt ideological shifts, moving from anti-clericalism and atheism to Roman Catholicism, and from an initial embrace of interventionism to an aversion to war. He also transitioned from individualism to conservatism, eventually aligning with Fascism in the 1930s, though he maintained an aversion to Nazism.

As a co-founder and editor of significant Italian literary and philosophical journals such as Leonardo and Lacerba, Papini conceived literature as "action," imbuing his writings with an oratorical and irreverent tone. Despite being largely self-educated, he became an iconoclastic editor and writer, playing a leading role in Futurism and other early youth literary movements in Italy. Working from Florence, he actively introduced foreign philosophical and political movements, including French intuitionism (particularly Bergson's) and American pragmatism (from thinkers like Peirce and James), to the Italian intellectual scene. His work, though temporarily forgotten after his death due to his controversial ideological choices, was later re-evaluated and appreciated by figures such as Jorge Luis Borges, who described him as an "undeservedly forgotten" author.

2. Early Life and Education

2.1. Birth and Family Background

Giovanni Papini was born in Florence, Italy, on January 9, 1881. His family background was modest; his father was a furniture retailer and a former member of Giuseppe Garibaldi's Redshirts, holding strong anti-clerical views. To circumvent his father's aggressive anti-clericalism, Papini was secretly baptized by his mother, who wished for him to have a religious upbringing.

2.2. Self-Education and Early Influences

Papini's childhood was characterized by a rustic and solitary nature. He was almost entirely self-educated, never obtaining an official university degree. His intellectual curiosity was evident from a young age, and he developed a strong aversion to all established beliefs, religions, and any form of servitude, which he perceived as being connected to religious institutions. This early skepticism fueled his ambition to write an encyclopedia that would summarize all cultures.

2.3. Academic and Professional Beginnings

Despite his self-taught background, Papini did receive some formal training at the Istituto di Studi Superiori in Florence from 1900 to 1902. Following this, he taught for a year at an Anglo-Italian school. From 1902 to 1904, he worked as a librarian at the Museum of Anthropology. However, it was the literary life that truly captivated Papini, leading him to found his first significant magazine in 1903.

3. Journalism and Literary Career Beginnings

Giovanni Papini's early career was defined by his foundational role in several influential Italian literary and philosophical journals, through which he introduced groundbreaking foreign philosophies and developed his distinct writing style.

3.1. Founding of "Leonardo" and "Lacerba"

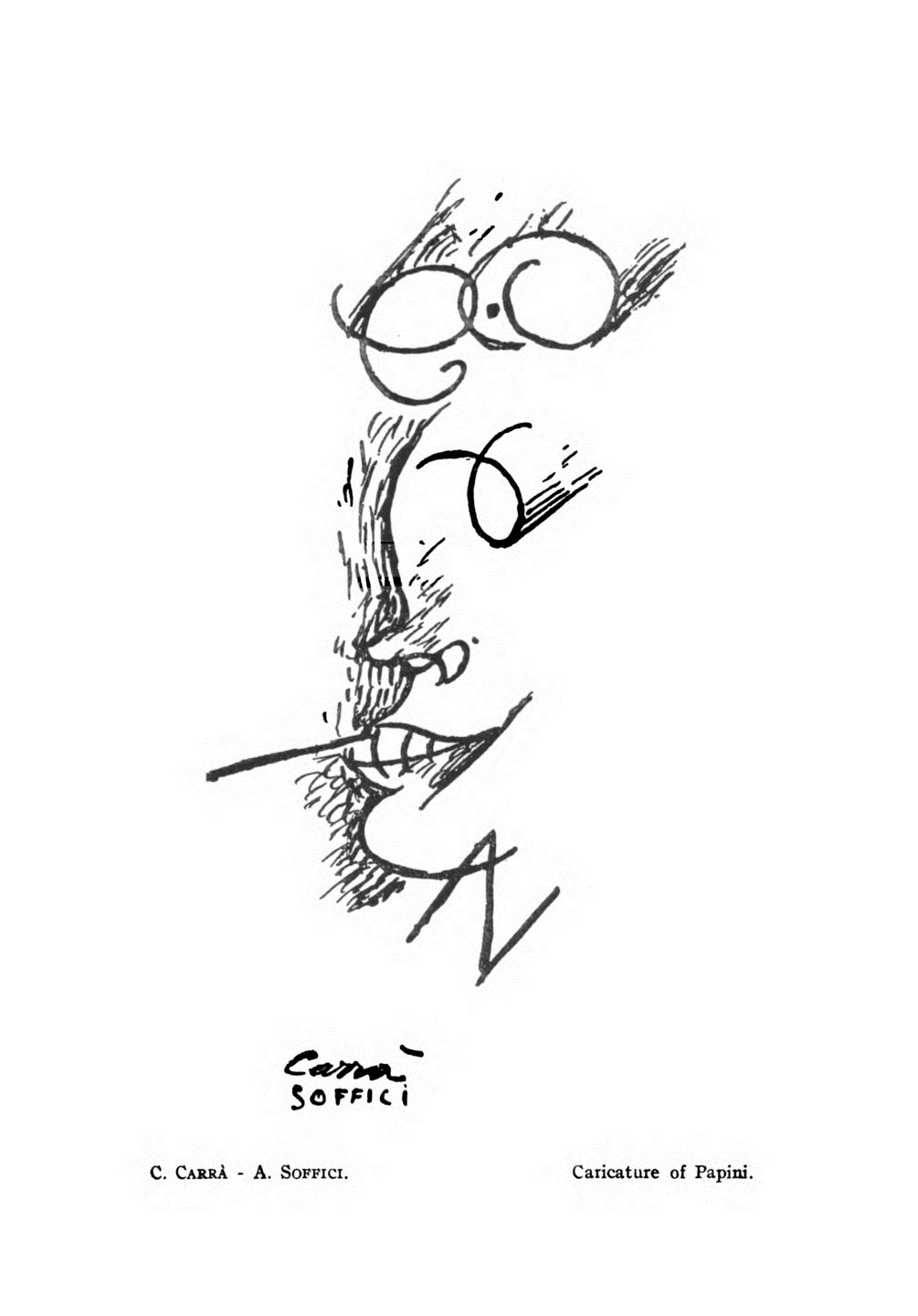

In 1903, Papini co-founded the magazine Il Leonardo (which ran until 1907), contributing articles under the pseudonym "Gian Falco." His collaborators on this venture included prominent intellectuals such as Giuseppe Prezzolini, Borgese, Vailati, Costetti, and Calderoni. After leaving Il Leonardo, Papini continued his journalistic endeavors, founding La Voce in 1908 and then L'Anima in collaboration with Giovanni Amendola and Prezzolini. In 1913, just before Italy's entry into World War I, he launched Lacerba, which was published until 1915. For three years, Papini also served as a correspondent for the Mercure de France and later as a literary critic for La Nazione. Around 1918, he co-created another review, La Vraie Italie, with Ardengo Soffici.

3.2. Introduction of Foreign Philosophies

Through Il Leonardo and his other publications, Papini played a crucial role in introducing significant foreign thinkers and philosophical movements to Italy. He actively promoted the works of American Pragmatists like Peirce and James, whose ideas greatly influenced his early writings. He also brought French intuitionism, particularly the philosophy of Bergson, to the attention of Italian intellectuals. Beyond these, Papini and his collaborators introduced other important figures such as Kierkegaard, Nietzsche, Santayana, and Poincaré.

3.3. Early Writings and Stylistic Development

Papini began his literary career by publishing a variety of essays and short stories. His initial publications included "Il Tragico Quotidiano" (Everyday Tragic) in 1906 and "Il Pilota Cieco" (The Blind Pilot) in 1907. In 1906, he also published "Il crepuscolo dei filosofi" ("The Twilight of the Philosophers"), a work that marked his emergence as a polemical writer. This book constituted a direct challenge to established and diverse intellectual figures such as Immanuel Kant, Hegel, Comte, Spencer, Schopenhauer, and Nietzsche, with Papini proclaiming the "death of philosophy" and advocating for the demolition of traditional thought.

His characteristic writing style, which was oratorical, irreverent, and polemical, became a hallmark of his work. In 1912, he published "Ventiquattro Cervelli" ("Twenty-Four Brains") and "Parole e Sangue" ("Words and Blood"), the latter of which explicitly showcased his fundamental atheism and controversially speculated on a homosexual relationship between Jesus and John the Apostle. His best-known early work, the autobiographical novel "Un Uomo Finito" ("A Finished Man" or "The Failure"), was published in 1913. In his 1915 collection of poetic prose, "Cento Pagine di Poesia" (One Hundred Pages of Poetry), followed by "Buffonate" (Buffooneries), "Maschilità" (Masculinity), and "Stroncature" (Censures), Papini engaged directly with literary giants like Boccaccio, Shakespeare, and Goethe, as well as contemporaries such as Croce and Gentile, and disciples of D'Annunzio.

4. Intellectual and Ideological Evolution

Giovanni Papini's intellectual and ideological journey was marked by a series of profound and often contradictory shifts, reflecting a restless search for truth and a persistent dissatisfaction with established norms.

4.1. Pragmatism and Avant-Garde Movements

In his early career, Papini was a fervent and early proponent of pragmatism in Italy, actively promoting the ideas of American philosophers like William James. He also became deeply involved with various avant-garde movements of the early 20th century, including Futurism and post-decadentism. He briefly flirted with Futurism and other forms of Modernism that he viewed as violent and liberating, aligning with a broader revolutionary and mythical political approach. His work from this period, such as "Sul Pragmatismo: Saggi e Ricerche, 1903-1911" (On Pragmatism: Essays and Research, 1903-1911), reflects this engagement.

4.2. Transition from Atheism to Catholicism

One of the most significant and dramatic ideological shifts in Papini's life was his conversion from aggressive anti-clericalism and atheism to Roman Catholicism. In his youth, he had vehemently denounced religious beliefs, as evidenced by works like "Parole e Sangue" (Words and Blood), which explicitly expressed his atheistic stance. However, after witnessing the widespread spiritual decay and disillusionment in Europe following World War I, Papini underwent a profound change. He announced his newfound faith in 1921, embracing the very concept of God he had once reviled. This conversion marked a pivotal moment in his life and literary output, leading him to dedicate much of his later work to religious themes.

4.3. Exploration of Individualism and Conservatism

Parallel to his religious conversion, Papini's political and philosophical outlook also evolved. He transitioned from an initial emphasis on individualism to a more conservative stance. This shift was part of a broader pattern of dissatisfaction and restlessness that characterized his intellectual trajectory, as he continually moved from one position to another in search of answers.

4.4. Key Early Works

Several seminal works from this period highlight Papini's evolving thought and literary prowess. His 1906 publication, "Il crepuscolo dei filosofi" ("The Twilight of the Philosophers"), established his reputation as a polemical and iconoclastic thinker who challenged the foundations of traditional philosophy. The autobiographical novel "Un uomo finito" ("A Finished Man"), published in 1913, is considered one of the fundamental works of modern Italian fiction. It provides deep insight into his early intellectual struggles and his restless pursuit of truth. Other notable works include "Ventiquattro Cervelli" (Twenty-Four Brains) from 1912.

5. Major Works and Religious Phase

Following his conversion to Catholicism, Giovanni Papini's literary and philosophical output largely shifted towards religious and spiritual themes, though he continued to engage with diverse intellectual subjects.

5.1. "Storia di Cristo" and Religious Writings

Papini's most influential work from his religious period is "Storia di Cristo" ("The Story of Christ"), published in 1921. This book marked his formal conversion to Catholicism and achieved immense worldwide success, being translated into twenty-three languages. Its widespread reception solidified his position as a prominent religious writer. Other significant religious and philosophical writings that followed include "Antologia della Poesia Religiosa Italiana" (Anthology of Italian Religious Poetry) in 1923, "L'Anno Santo e le Quattro Paci" (The Holy Year and the Four Peaces) in 1925, and "Sant'Agostino" (Saint Augustine) in 1930. He also published "Gli Operai della Vigna" (Laborers in the Vineyard) in 1929, "La Scala di Giacobbe" (Jacob's Ladder) in 1932, "I Testimoni della Passione" (The Witnesses of the Passion) in 1937, "Cielo e Terra" (Heaven and Earth) in 1943, and "Santi e Poeti" (Saints and Poets) in 1948. In 1953, he published "Il Diavolo" (The Devil), a work exploring diabology.

5.2. Later Literary and Philosophical Works

Beyond his religious writings, Papini continued to produce important literary and philosophical works that showcased his broad intellectual interests. His 1931 satire, "Gog", presented a critical view of modern society through the eyes of a fictional character. In 1933, he published the essay "Dante Vivo" ("Living Dante," or "If Dante Were Alive"), a study of the medieval poet Dante. Later in his career, he wrote a biography of Michelangelo titled "Vita di Michelangiolo" (Life of Michelangelo), published in 1949, and the controversial 1951 novel "Il libro nero" (The Black Book), which featured a series of imaginary interviews.

6. Political Engagements and Historical Context

Giovanni Papini's life was intertwined with the turbulent political landscape of early 20th-century Italy, marked by his shifting allegiances and controversial affiliations.

6.1. Interventionism and World War I

Before 1915, Papini was a convinced supporter of Italian interventionism in World War I. His early publications and journalistic activities often reflected a nationalist fervor. However, his stance on war evolved significantly; after experiencing the realities and consequences of the conflict, he developed a strong aversion to war. This shift mirrored his broader pattern of ideological changes throughout his life.

6.2. Nationalistic and Fascist Affiliations

Papini's political leanings saw him move towards nationalist movements early in his career. He joined the staff of Il Regno, a nationalist publication directed by Enrico Corradini, who founded the Associazione Nazionalistica Italiana to support Italy's colonial expansionism. This marked an early engagement with nationalist ideologies. In the 1930s, after his shift from individualism to conservatism, Papini eventually aligned himself with Fascism. His embrace of the Fascist regime led to significant academic appointments; in 1935, he became a teacher at the University of Bologna, an appointment confirmed by Fascist authorities who lauded his "impeccable reputation." In 1937, Papini published the only volume of his "History of Italian Literature", which he controversially dedicated to Benito Mussolini, addressing him as "Il Duce (the Leader), friend of poetry and of the poets." This dedication, along with his academic positions, underscored his integration into the Fascist cultural apparatus. In 1940, his "Storia della Letteratura Italiana" was published in Nazi Germany under the title "Eternal Italy: The Great in its Empire of Letters" (Ewiges Italien - Die Großen im Reich seiner DichtungEwiges Italien - Die Großen im Reich seiner DichtungGerman).

6.3. European Writers' League

Papini's involvement with Fascism extended to international collaborations. He served as the vice president of the Europäische Schriftstellervereinigung (European Writers' League), an organization founded by Joseph Goebbels in 1941-1942. This league was a Nazi-backed initiative aimed at promoting a unified European literature aligned with Fascist and Nazi ideologies. When the Fascist regime collapsed in 1943, Papini sought refuge in a Franciscan convent in La Verna, adopting the name "Fra' Bonaventura."

7. Controversies and Propaganda

Giovanni Papini's life and works were frequently embroiled in controversy, largely due to his dramatic ideological shifts and the subsequent use of his writings for political propaganda.

7.1. Criticisms of Ideological Shifts

Papini was known for his restless and often abrupt changes in political and philosophical stances. He moved from one position to another, always appearing dissatisfied and uneasy. This pattern of conversion, from anti-clericalism and atheism to Catholicism, and from interventionism to aversion to war, drew significant criticism. His later alignment with Fascism, despite his earlier anti-establishment views, further complicated his public image and led to a period of discrediting after World War II. His work was almost forgotten in the immediate aftermath of his death, reflecting the controversies surrounding his ideological choices.

7.2. Use in Political Propaganda

One of the most notable instances of his work being used for political purposes involved his 1951 novel "Il libro nero" ("The Black Book"). This book contained a series of imaginary interviews, including one with the renowned artist Pablo Picasso. According to art historian Richard Dorment, Francisco Franco's regime in Spain and NATO intelligence during the Cold War exploited this "interview" as propaganda against Picasso, aiming to undermine his pro-Communist image. The fabricated quotes attributed to Picasso in Papini's book were widely disseminated. In 1962, Picasso himself asked his biographer, Pierre Daix, to expose the pretend interview, which Daix did through a series of articles in Les Lettres Françaises. Daix described the contents of "Il libro nero" as "imaginary interviews and false confessions," clarifying that Papini, while a journalist who used literary devices like pretend interviews, never actually met Picasso or received the attributed statements from him.

7.3. Relationship with Nazism

Despite his alignment with Italian Fascism and his involvement with the Nazi-backed European Writers' League, Papini maintained a distinct aversion to Nazism. This nuance in his political stance highlights the complexities of ideological allegiances during the interwar period and World War II, where Fascism and Nazism, while allied, were not always ideologically identical in the minds of their adherents.

8. Personal Life

Giovanni Papini's personal life included his marriage and significant romantic relationships that influenced his literary work.

8.1. Marriage and Family

In 1907, Giovanni Papini married Giacinta Giovagnoli. The couple had two daughters. His family life provided a backdrop to his intense intellectual and literary pursuits.

8.2. Personal Relationships

Papini also had other significant personal relationships, including an affair with the modernist poet Mina Loy. Loy, in turn, referenced Papini as a character in several of her poems from that period, indicating the impact of their relationship on her creative output.

9. Later Years and Death

Giovanni Papini's final years were marked by severe health challenges, yet he continued his intellectual endeavors until his death.

9.1. Health Challenges and Continued Work

In his later years, Papini suffered from progressive paralysis, which was attributed to motor neuron disease. He also experienced blindness, which severely impacted his ability to write. Despite these debilitating conditions, his mind remained remarkably clear. He continued his intellectual output through dictation and collaboration, demonstrating an enduring commitment to his craft. His posthumously published work, "Le Felicità dell'Infelice" (The Happiness of the Unhappy), was dictated during this period. He also collaborated with Corriere della Sera, contributing articles that were later collected and published as a volume after his death.

9.2. Death and Burial

Giovanni Papini died at the age of 75 on July 8, 1956. He was buried in the Cimitero delle Porte Sante (Cemetery of the Holy Gates) in his native Florence.

10. Reception and Legacy

Giovanni Papini's complex and often controversial legacy has undergone significant re-evaluation since his death, with critics and writers offering diverse assessments of his enduring influence.

10.1. Posthumous Re-evaluation

Following his death, Papini's work largely fell into obscurity, a consequence of his controversial ideological choices and affiliations, particularly with Fascism. However, his literary contributions were later re-evaluated and appreciated. In 1975, the renowned Argentine writer Jorge Luis Borges publicly called Papini an "undeservedly forgotten" author, even including some of his stories in his influential "Library of Babel" series. Papini was also admired by Bruno de Finetti, a key figure in the subjective theory of probability.

10.2. Critical Assessment

Papini was widely admired for his distinctive writing style, which was characterized by its oratorical, irreverent, and polemical tone. He frequently engaged in heated debates and intellectual confrontations. As an editor, he was an influential and iconoclastic figure, playing a leading role in early 20th-century Italian literary movements, including Futurism. His work reflected a restless search for truth and a constant dissatisfaction with existing intellectual and social norms. In his later life, he became a prominent spokesman for Roman Catholic religious beliefs, influencing a generation of readers with works like "Storia di Cristo." Critics have noted his "proud spiritual impulses," "restless ardour," "wealth of new and provocative ideas," and "crashing judgments" as a strong stimulus to younger generations, drawing even independent writers to his side, if only temporarily.

10.3. Enduring Influence

Despite the controversies surrounding his ideological shifts, Papini left a lasting impact on Italian literature, philosophy, and culture. His efforts to introduce foreign philosophical currents like American Pragmatism and French Bergsonism significantly shaped the Italian intellectual landscape of the early 20th century. His literary works, particularly his autobiographical novel "Un Uomo Finito" and his religious magnum opus "Storia di Cristo", continue to be studied for their literary merit and their reflection of the complex intellectual currents of his time. His influence is recognized across various fields, from literature to philosophy.

11. Publications

11.1. Major Works

- La Teoria Psicologica della Previsione (1902)

- Sentire Senza Agire e Agire Senza Sentire (1905)

- Il crepuscolo dei filosofi (1906)

- Lo specchio che fugge (1906)

- Il Tragico Quotidiano (1906)

- La Coltura Italiana (with Giuseppe Prezzolini, 1906)

- Il Pilota Cieco (1907)

- Le Memorie d'Iddio (1911)

- L'Altra Metà (1911)

- La Vita di Nessuno (1912)

- Parole e Sangue (1912)

- Un Uomo Finito (1913)

- Ventiquattro Cervelli (1913)

- Sul Pragmatismo: Saggi e Ricerche, 1903-1911 (1913)

- Almanacco Purgativo 1914 (with Ardengo Soffici et al., 1913)

- Buffonate (1914)

- Vecchio e Nuovo Nazionalismo (with Giuseppe Prezzolini, 1914)

- Cento Pagine di Poesia (1915)

- Maschilità (1915)

- La Paga del Sabato (1915)

- Stroncature (1916)

- Opera Prima (1917)

- Polemiche Religiose (1917)

- Testimonianze (1918)

- L'Uomo Carducci (1918)

- L'Europa Occidentale Contro la Mittel-Europa (1918)

- Chiudiamo le Scuole (1918)

- Giorni di Festa (1918)

- L'Esperienza Futurista (1919)

- Poeti d'Oggi (with Pietro Pancrazi, 1920)

- Storia di Cristo (1921)

- Antologia della Poesia Religiosa Italiana (1923)

- Dizionario dell'Omo Salvatico (with Domenico Giuliotti, 1923)

- L'Anno Santo e le Quattro Paci (1925)

- Pane e Vino (1926)

- Gli Operai della Vigna (1929)

- Sant'Agostino (1931)

- Gog (1931)

- La Scala di Giacobbe (1932)

- Firenze (1932)

- Il Sacco dell'Orco (1933)

- Dante Vivo (1933)

- Ardengo Soffici (1933)

- La Pietra Infernale (1934)

- Grandezze di Carducci (1935)

- I Testimoni della Passione (1937)

- Storia della Letteratura Italiana (1937)

- Italia Mia (1939)

- Figure Umane (1940)

- Medardo Rosso (1940)

- La Corona d'Argento (1941)

- Mostra Personale (1941)

- Prose di Cattolici Italiani d'Ogni Secolo (with Giuseppe De Luca, 1941)

- L'Imitazione del Padre. Saggi sul Rinascimento (1942)

- Racconti di Gioventù (1943)

- Cielo e Terra (1943)

- Foglie della Foresta (1946)

- Lettere agli Uomini di Papa Celestino VI (1946)

- Primo Conti (1947)

- Santi e Poeti (1948)

- Passato Remoto (1948)

- Vita di Michelangiolo (1949)

- Le Pazzie del Poeta (1950)

- Firenze Fiore del Mondo (with Ardengo Soffici, Piero Bargellini and Spadolini, 1950)

- Il libro nero (1951)

- Il Diavolo (1953)

- Il Bel Viaggio (with Enzo Palmeri, 1954)

- Concerto Fantastico (1954)

- Strane Storie (1954)

- La Spia del Mondo (1955)

- La Loggia dei Busti (1955)

- Le Felicità dell'Infelice (1956)

11.2. Collected Works and Translations

Papini's collected works were published posthumously as Tutte le Opere di Giovanni Papini, in 11 volumes, by Mondadori between 1958 and 1966. Many of his major works have been translated into English, including:

- Four and Twenty Minds. New York: Thomas Y. Crowell Company, 1922.

- The Story of Christ. London: Hodder and Stoughton, 1923 (republished as Life of Christ. New York: Harcourt, Brace and Co., 1923).

- The Failure. New York: Harcourt, Brace and Company, 1924.

- A Man - Finished. London: Hodder & Stoughton, 1924.

- The Memoirs of God. Boston: The Ball Publishing Co., 1926.

- A Hymn to Intelligence. Pittsburgh: The Laboratory Press, 1928.

- A Prayer for Fools, Particularly Those we See in Art Galleries, Drawing-rooms and Theatres. Pittsburgh: The Laboratory Press, 1929.

- Laborers in the Vineyard. London: Sheed & Ward, 1930.

- Life and Myself, translated by Dorothy Emmrich. New York: Brentano's, 1930.

- Saint Augustine. New York: Harcourt, Brace and Co., 1930.

- Gog, translated by Mary Prichard Agnetti. New York: Harcourt, Brace and Co., 1931.

- Dante Vivo. New York: The Macmillan Company, 1935.

- The Letters of Pope Celestine VI to All Mankind. New York: E.P. Dutton & Co., Inc., 1948.

- Florence: Flower of the World. Firenze: L'Arco, 1952 (with Ardengo Soffici and Piero Bargellini).

- Michelangelo, his Life and his Era. New York: E. P. Dutton, 1952.

- The Devil; Notes for Future Diabology. New York: E.P. Dutton, 1954 (London: Eyre & Spottiswoode, 1955).

- Nietzsche: An Essay. Mount Pleasant, Mich.: Enigma Press, 1966.

- "The Circle is Closing." In: Lawrence Rainey (ed.), Futurism: An Anthology, Yale University Press, 2009.

11.3. Selected Articles and Short Stories

Giovanni Papini's extensive bibliography also includes numerous articles and short stories published in various journals and magazines throughout his career.

Selected articles include:

- "Philosophy in Italy," The Monist 8 (4), July 1903, pp. 553-585.

- "What Pragmatism is Like," Popular Science Monthly, Vol. LXXI, October 1907, pp. 351-358.

- "The Historical Play," The Little Review 6 (2), pp. 49-51.

- "Ignoto," The New Age 26 (6), 1919, p. 95.

- "Buddha," The New Age 26 (13), 1920, pp. 200-201.

- "Rudolph Eucken" The Open Court, 38 (5), May 1924, pp. 257-261.

A selection of his short stories includes:

- "The Debt of a Day," The International 9 (4), 1915, pp. 105-107.

- "The Substitute Suicide," The International 10 (5), 1916, pp. 148-149.

- "Four-Hundred and Fifty-Three Love Letters," The Stratford Journal 3 (1), 1918, pp. 9-12.

- "The Beggar of Souls" The Stratford Journal 4, 1919, pp. 59-64.

- "Life: The Vanishing Mirror," Vanity Fair 13 (6), 1920, p. 53.

- "Don Juan's Lament," Vanity Fair 13 (10), 1920, p. 43.

- "An Adventure in Introspection," Vanity Fair 13 (10), 1920, p. 65.

- "Having to do with Love - and Memory," Vanity Fair 14 (2), 1920, p. 69.

- "For no Reason," Vanity Fair 14 (3), 1920, pp. 71, 116.

- "The Prophetic Portrait," Vanity Fair 14 (4), 1920, p. 73.

- "The Man who Lost Himself," Vanity Fair 14 (5), 1920, p. 35.

- "Hope," Vanity Fair 14 (6), 1920, p. 57.

- "The Magnanimous Suicide," Vanity Fair 15 (1), 1920, p. 73.

- "The Lost Day," Vanity Fair 15 (3), 1920, pp. 79, 106.

- "Two Faces in the Well," Vanity Fair 15 (4), 1920, p. 41.

- "Two Interviews with the Devil," Vanity Fair 15 (5), 1921, pp. 59, 94.

- "The Bartered Souls," Vanity Fair 15 (6), 1921, p. 57.

- "The Man Who Could Not be Emperor," Vanity Fair 16 (1), 1921, p. 41.

- "A Man Among Men - No More," Vanity Fair 16 (2), 1921.

- "His Own Jailer," The Living Age, December 9, 1922.

- "Pallas and the Centaur," Italian Literary Digest 1 (1), April 1947.

12. In Popular Culture

Giovanni Papini's life and work have occasionally appeared in other literary and cultural contexts, reflecting his impact on contemporaries and later artists.

- Papini appears as a character in several poems of the period written by Mina Loy, with whom he had an affair.

- The American poet Wallace Stevens wrote a poem titled "Reply to Papini."

- Papini is repeatedly mentioned in speeches made by the Colombian writer Gabriel García Márquez.