1. Life

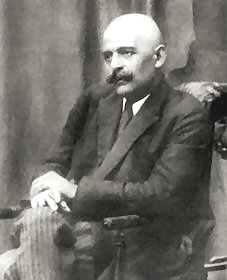

George Ivanovich Gurdjieff's life was marked by extensive travels, profound spiritual inquiry, and the establishment of a unique teaching system that attracted a diverse array of students across Russia, Europe, and North America.

1.1. Early Life and Background

Gurdjieff was born in Alexandropol, Yerevan Governorate, Russian Empire (now Gyumri, Armenia). His exact birth year is subject to conflicting accounts, ranging from 1866 to 1877. While official documents lean towards 1877, Gurdjieff himself reportedly stated his birth year as circa 1867. His niece, Luba Gurdjieff Everitt, corroborated the 1867 date, which also aligns with photographs and videos from his later life. However, his paternal great-grandnephew, George Kiourtzidis, recalled his grandfather Alexander (born 1875) saying Gurdjieff was about three years older, suggesting a birth date around circa 1872. The year 1872 is also inscribed on his grave marker in Avon, France. Despite official records listing 28 December as his birth date, Gurdjieff celebrated his birthday either on 1 January (Julian calendar) or 13/14 January (Gregorian calendar).

His father, Ivan Ivanovich Gurdjieff, was of Greek descent, whose ancestors reportedly emigrated from Byzantium after the Fall of Constantinople in 1453, moving first to central Anatolia and then to the Caucasus. Ivan was a renowned ashik (bardic poet) and, in the 1870s, managed large herds of cattle and sheep before economic hardship from a cattle plague led him to establish a small carpentry workshop. Gurdjieff's mother was widely believed to be Armenian, though some recent scholarship speculates she was also Greek, citing Gurdjieff's German papers identifying him as Greek and his assertion that Greek was his mother tongue.

Gurdjieff spent his childhood in Kars, which from 1878 to 1918 was the administrative capital of the Russian-ruled Kars Oblast, a multi-ethnic and multi-confessional border region recently acquired after the Russo-Turkish War (1877-1878). This environment, home to Armenians, Caucasus Greeks, Pontic Greeks, Georgians, Russians, Kurds, Turks, and various Christian communities, fostered a respect for traveling mystics and religious syncretism. Gurdjieff specifically mentioned the Yazidi community. Growing up in this diverse society, Gurdjieff became fluent in Armenian, Pontic Greek, Russian, and Turkish (a mixture of elegant Ottoman Turkish with some dialect), later acquiring proficiency in several European languages.

Early influences included his father, who recited the Epic of Gilgamesh, and Dean Borsh, the priest of the Cathedral of Kars and a family friend. Gurdjieff avidly read diverse literature. Witnessing unexplainable phenomena, he became convinced of a hidden truth known in the past, inaccessible through conventional science or mainstream religion. This conviction spurred his lifelong quest.

1.2. Travels and Search for Knowledge

In his early adulthood, Gurdjieff embarked on extensive travels across Central Asia, Egypt, Iran, India, Tibet, and other regions, reportedly in pursuit of hidden knowledge and ancient wisdom. These wanderings, which he recounted in his book Meetings with Remarkable Men, are not considered a reliable autobiography, often presenting allegorical or embellished narratives. For instance, he described walking across the Gobi Desert on stilts to observe sand dune contours above a sandstorm.

His search was for esoteric teachings, leading him to encounter various spiritual traditions. He described meeting dervishes, fakirs, and descendants of the Essenes, whose teachings he claimed were preserved in a monastery in Sarmoung. The book culminates in an encounter with the "Sarmoung Brotherhood" and involves a quest related to a map of "pre-sand Egypt." He once labeled his teaching as esoteric Christianity, interpreting biblical parables psychologically rather than literally.

Gurdjieff supported himself during his travels through various enterprises, such as running a traveling repair shop and making paper flowers. In one instance, he recounted catching sparrows, dyeing them yellow, and selling them as canaries. Commentators speculate he may have also engaged in political activities as part of The Great Game. He recalled being shot three times during his travels: in Crete a year before the Greco-Turkish War (1897), in Tibet a year before the 1903 British invasion, and in Transcaucasia during the 1904 civil unrest. These dangerous missions suggest he might have relied on external support or political protection, leading to speculation about his involvement with Armenian or Greek ethnic movements, or the Great Game between Britain and Russia, and even his potential role in relation to the 13th Dalai Lama. However, definitive proof remains scarce.

Gurdjieff also developed an interest in hypnosis, viewing it as a means to understand the division between conscious and subconscious minds and their hidden connections. This interest extended to studying human susceptibility to "mass hypnosis," particularly evident during wars and civil unrest. He stated that his quest had two main objectives: to understand the meaning and purpose of human life, and to find ways to remove human vulnerability to external influences that lead to "mass hypnosis."

1.3. Activities in Russia

Gurdjieff ended his period of extensive travels around 1912, arriving in Moscow on New Year's Day. He began attracting his first students, including his cousin, the sculptor Sergey Merkurov, and the eccentric Rachmilievitch. In the same year, he married the Polish Julia Ostrowska in Saint Petersburg. By 1914, he was advertising his ballet, The Struggle of the Magicians, and supervising his pupils in writing the sketch Glimpses of Truth.

In 1915, Gurdjieff accepted P. D. Ouspensky, already a renowned writer on mystical subjects, as a pupil. In 1916, the composer Thomas de Hartmann and his wife, Olga, also became his students. At this time, Gurdjieff had approximately 30 pupils. The "Fourth Way" system taught during this period was complex, metaphysical, and partly expressed in scientific terminology.

During the revolutionary upheaval in Russia, Gurdjieff left Petrograd in 1917 to return to his family home in Alexandropol (present-day Gyumri). Amidst the October Revolution, he established a temporary study community in Essentuki in the Caucasus. Here, he worked intensively with a small group of Russian pupils, focusing on more physical aspects of the work. His eldest sister, Anna, and her family arrived as refugees, informing him that his father had been shot in Alexandropol on 15 May. As the civil war intensified, Gurdjieff fabricated a newspaper story about a "scientific expedition" to "Mount Induc" to secure permission and supplies from the government. Posing as a scientist, he departed Essentuki on 6 August 1918, with fourteen companions (excluding his family and Ouspensky). They traveled through dangerous areas, crossing the front lines five times on foot through the Caucasus, eventually reaching the Black Sea resort of Sochi.

In March 1918, Ouspensky separated from Gurdjieff, settling in England to teach the Fourth Way independently. Their relationship remained ambivalent for decades.

1.4. Activities in Europe

In 1919, Gurdjieff and his closest pupils moved to Tbilisi, Georgia. His wife Julia Ostrowska, the Stjoernvals, the Hartmanns, and the de Salzmanns continued their studies. Gurdjieff focused on his ballet, The Struggle of the Magicians, with Thomas de Hartmann composing the music and Olga Ivanovna Hinzenberg practicing the dances. It was in Tbilisi that Gurdjieff opened his first Institute for the Harmonious Development of Man. With the collaboration of artist Alexandre de Salzmann and his wife Jeanne, Gurdjieff gave the first public demonstration of his Sacred Dances (Movements) at the Tbilisi Opera House on 22 June 1919.

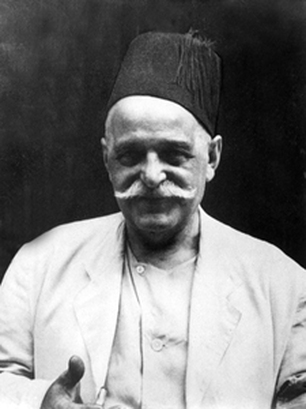

By late May 1920, as political and social conditions in Georgia deteriorated, Gurdjieff's party traveled to Batumi on the Black Sea coast and then by ship to Constantinople (now Istanbul). In Istanbul, Gurdjieff rented apartments on Kumbaracı Street in Péra and later at 13 Abdullatif Yemeneci Sokak near the Galata Tower. These locations were near the Khanqah (Sufi lodge) of the Mevlevi Order, where Gurdjieff, Ouspensky, and Thomas de Hartmann witnessed the Sama ceremony of the Whirling Dervishes. In Istanbul, Gurdjieff also met his future pupil, Captain John G. Bennett, then head of the British Directorate of Military Intelligence in Ottoman Turkey. Bennett described Gurdjieff as a "Greek from the Caucasus" who spoke Turkish with "unexpected purity," possessing a striking appearance with a shaven head, immense black mustache, and eyes that shifted in color.

In August 1921 and 1922, Gurdjieff toured western Europe, lecturing and demonstrating his work in cities like Berlin and London. He attracted the allegiance of many of Ouspensky's prominent pupils, notably the editor A. R. Orage. After an unsuccessful attempt to obtain British citizenship, Gurdjieff established the Institute for the Harmonious Development of Man in October 1922, south of Paris at the Prieuré des Basses Loges in Avon, near the famous Château de Fontainebleau. This once-impressive but crumbling mansion housed an entourage of several dozen, including Gurdjieff's remaining relatives and White Russian refugees. An aphorism at the Prieuré stated: "Here there are neither Russians nor English, Jews nor Christians, but only those who pursue one aim-to be able to be." Gurdjieff himself was quoted as saying, "The Institute can help one to be able to be a Christian."

New pupils included C. S. Nott, René Zuber, Margaret Anderson, and her ward Fritz Peters. Many intellectual and middle-class students found the Prieuré's spartan accommodation and emphasis on hard labor disconcerting. Gurdjieff's teaching at the Prieuré integrated lectures, music, dance, and manual work, aiming for physical, emotional, and intellectual development. Older pupils noted a difference from the complex metaphysical "system" taught in Russia. Gurdjieff's personal behavior could be intense; Fritz Peters recalled an instance where Gurdjieff's "uncontrolled fury" at A. R. Orage instantly transformed into a "broad smile" and then resumed with "undiminished force."

Gurdjieff gained notoriety as "the man who killed Katherine Mansfield" after the renowned New Zealand writer Katherine Mansfield died of tuberculosis at the Prieuré on 9 January 1923. However, scholars like James Moore and Ouspensky argued that Mansfield knew her death was imminent and that Gurdjieff helped make her final days happy and fulfilling. Her death coincided with the celebration of the completion of the "Study House," a building constructed by Gurdjieff and his students from airship hangar scraps, used for practicing the Movements.

1.5. Visits to North America

Beginning in 1924, Gurdjieff made several visits to North America, where he took over the pupils previously taught by A. R. Orage. In 1924, while driving alone from Paris to Fontainebleau, he suffered a near-fatal car accident. Nursed by his wife and mother, he made a slow and painful recovery against medical expectations. While still convalescing, he formally "disbanded" his institute on 26 August, a move he described as a personal undertaking to remove those who made his life "too comfortable."

During his recovery, too weak to write himself, he began dictating his magnum opus, Beelzebub's Tales to His Grandson, the first part of All and Everything, in a mixture of Armenian and Russian. He continued developing the book over several years, often writing in noisy cafes, which he found conducive to his thoughts. The book is generally considered convoluted and obscure, requiring the reader to "work" to find its meaning.

Gurdjieff's mother died in 1925, and his wife, Julia Ostrowska, died of cancer in June 1926, with Ouspensky attending her funeral. According to writer Fritz Peters, Gurdjieff was in New York from November 1925 to spring 1926, raising over 100.00 K USD. He made six or seven trips to the US, but his blunt demands for money alienated some people.

In 1927, Jean Toomer, who had trained at the Prieuré for a year, founded a Gurdjieff group in Chicago. Diana Huebert, a regular member, documented Gurdjieff's visits to this group in 1932 and 1934 in her memoirs.

The Prieuré operation eventually ran into debt and was shut down in 1932. Gurdjieff then formed a new teaching group in Paris, known as "The Rope," composed exclusively of women, many of whom were writers and several were lesbians. Members included Kathryn Hulme, Jane Heap, Margaret Anderson, and Enrico Caruso's widow, Dorothy. Gurdjieff became acquainted with Gertrude Stein through these members, though she never became a follower.

In 1935, Gurdjieff ceased work on All and Everything, having completed the first two parts of the planned trilogy. He then began the Third Series, later published as Life Is Real Only Then, When 'I Am'. In 1936, he settled at a flat at 6, Rue des Colonels-Renard in Paris, where he would live for the remainder of his life. His brother Dmitry died in 1937, and "The Rope" group disbanded.

1.6. Later Years and World War II

Despite the small size of his flat at 6 Rue des Colonels-Renard, Gurdjieff continued to teach groups of pupils there throughout World War II and the German occupation of Paris (from June 1940). Visitors described his pantry, or "inner sanctum," as being stocked with an extraordinary collection of Eastern delicacies. He held suppers featuring elaborate toasts with vodka and cognac to "idiots." Having been physically impressive for many years, he was now paunchy. His teaching during this period was conveyed more directly through personal interaction with his pupils, who were encouraged to study the ideas expressed in Beelzebub's Tales. During this time, he also began creating a series of Movements, now known as the "Thirty-Nine Series."

His various business enterprises, including intermittently dealing in oriental rugs and carpets, allowed him to provide charitable relief to neighbors affected by the war's difficult circumstances. These activities also drew the attention of authorities, leading to him spending a night in the cells.

1.7. Death

After the war, Gurdjieff sought to reconnect with his former pupils. While Ouspensky was hesitant, after Ouspensky's death in October 1947, his widow advised his remaining pupils to visit Gurdjieff in Paris. John G. Bennett also visited from England, their first meeting in 25 years. Many of Ouspensky's pupils, who had believed Gurdjieff was dead, were overjoyed to discover he was alive and visited him in Paris. Rina Hands and Catherine Murphy assisted with the typing and retyping for the publication of All and Everything.

Gurdjieff suffered a second car accident in 1948 but again made an unexpected recovery. John G. Bennett described him emerging from the car like a "dead man, a corpse," yet walking. Gurdjieff reportedly said, "Now all organs are destroyed. Must make new," and then, smiling, "Tonight you come dinner. I must make body work."

After his recovery, Gurdjieff finalized plans for the official publication of Beelzebub's Tales and made two more trips to New York. He also visited the famous prehistoric cave paintings at Lascaux, offering his interpretation of their significance to his pupils.

George Ivanovich Gurdjieff died of cancer at the American Hospital in Neuilly-sur-Seine, France, on 29 October 1949. His funeral took place at the St. Alexandre Nevsky Russian Orthodox Cathedral at 12 Rue Daru, Paris. He is buried in the cemetery at Avon (near Fontainebleau), alongside his mother and wife, and near Katherine Mansfield.

2. Personal Life

Information regarding Gurdjieff's personal life is somewhat limited, often relying on anecdotal accounts rather than verifiable documents. He was married to Julia Ostrowska, who died of cancer in June 1926. His mother also passed away around the same time. Both women are buried in the cemetery at Avon, France.

While no definitive evidence or documents have certified anyone as a child of Gurdjieff, the following six individuals are commonly cited as his children:

- Nikolai Stjernvall (1919-2010), whose mother was Elizaveta Grigorievna, wife of Leonid Robertovich de Stjernvall.

- Michel de Salzmann (1923-2001), whose mother was Jeanne Allemand de Salzmann. Michel later became head of the Gurdjieff Foundation.

- Cynthie Sophia "Dushka" Howarth (1924-2010), whose mother was dancer Jessmin Howarth. Dushka later founded the Gurdjieff Heritage Society.

- Eve Taylor (born 1928), whose mother was American socialite Edith Annesley Taylor.

- Sergei Chaverdian, whose mother was Lily Galumnian Chaverdian.

- Andrei, born to a mother known only as Georgii.

Gurdjieff also had a niece, Luba Gurdjieff Everitt, who ran a small but famous restaurant, Luba's Bistro, in Knightsbridge, London, for about 40 years (1950s-1990s).

3. Ideas and Teachings

Gurdjieff's teachings, often referred to as "my ideas" or "the Work," present a unique worldview and understanding of human nature and the universe. His approach aimed at practical transformation rather than mere intellectual pursuit.

3.1. Core Concepts

Gurdjieff taught that most people live in a state of hypnotic "waking sleep," characterized by constantly turning thoughts, worries, and imagination, preventing them from perceiving reality as it truly is. He famously stated, "Man lives his life in sleep, and in sleep he dies." He asserted that in their ordinary state, humans function as unconscious automatons, but that it is possible to "wake up" and achieve a higher state of consciousness.

The core of his teaching is "The Work" or "Work on oneself," which is a practical way of living "in the moment" to allow for the emergence of "self-remembering"-a constant sensation of one's individuality that cannot be expressed intellectually because it is organic and fosters independence. Gurdjieff emphasized that "Working on oneself is not so difficult as wishing to work, taking the decision."

He argued that many existing forms of religious and spiritual traditions had lost their original meaning and vitality, thus failing to help humanity realize its full potential. He believed that these traditions often led to one-sided development, neglecting either emotions, the physical body, or the mind, which he called "centers." This imbalance, he argued, prevented the creation of a properly integrated human being and made people susceptible to "mass psychosis," as seen in events like World War I.

Gurdjieff reduced traditional paths to spiritual knowledge to three: the way of the Fakir (through pain), the way of the Monk (through devotion), and the way of the Yogi (through study), all of which required renouncing worldly life. In contrast, he described a "Fourth Way" that was amenable to contemporary people living in society. This path aimed to train the mind, body, and emotions simultaneously, promoting an organic connection and balanced development. Although Gurdjieff himself did not emphasize the term "Fourth Way" in his writings, his pupil P. D. Ouspensky made it central to his interpretation of Gurdjieff's teaching, publishing a book titled The Fourth Way based on his lectures.

Gurdjieff's teaching also addressed humanity's place in the universe and the importance of developing latent potentialities-our natural endowment that is rarely brought to fruition. He taught that higher levels of consciousness, higher bodies, and inner growth are real possibilities requiring conscious effort. The aim was not to acquire anything new but to recover what had been lost. He gave distinct meanings to ancient texts, such as the Bible, believing their essence had been forgotten, with statements like "Sleep not" and "The Kingdom of Heaven is Within" pointing to deeper, psychological truths.

He stressed the importance of "conscience" over "morality," which he viewed as culturally variable, often contradictory, and hypocritical.

3.2. Human Potential and Consciousness

Gurdjieff's central premise was that humans possess an unrealized potential for higher consciousness. He believed that the ordinary human state is one of "waking sleep," where individuals are largely unconscious and function as automatons, driven by external influences and habitual patterns. His teachings aimed to awaken individuals from this state, enabling them to achieve a more complete and conscious state of being. This transformation, referred to as "The Work," required significant personal effort and self-observation.

He argued that true human development involved integrating the three "centers"-physical (moving/instinctive), emotional, and intellectual-which typically operate independently and out of balance. By bringing these centers into harmony, individuals could transcend their mechanical nature and realize their inherent capacities for conscious action and genuine individuality. The goal was to recover an innate wholeness rather than acquiring something new.

3.3. Cosmology and Mysticism

Gurdjieff's teachings included a complex cosmology that described universal laws governing existence. While distinct, his views showed connections and influences from various mystical, philosophical, and religious traditions. He drew parallels with Sufism, particularly its emphasis on inner work and the concept of dervishes. Elements of Gnosticism can be seen in his emphasis on awakening from an illusory state and the pursuit of hidden knowledge. His ideas also resonated with aspects of Buddhism, with his concept of self-remembering being compared to the Buddhist notion of "mindfulness" or "sati," meaning "to remember."

His teachings also incorporated elements reminiscent of ancient Greek philosophy, such as the Socratic emphasis on "know thyself" reflected in his practice of self-observation. His stress on self-discipline and restraint echoed Stoicism. The Hindu and Buddhist concept of attachment found a parallel in Gurdjieff's idea of "identification." His descriptions of "three being-foods" aligned with Ayurveda, and his statement that "time is breath" resonated with Jyotish, the Vedic system of astrology. Furthermore, his cosmology could be interpreted through Neoplatonic lenses and sources like Robert Fludd's macrocosmic musical structures.

A prominent aspect of Gurdjieff's teachings that gained widespread attention, particularly in recent decades, is the enneagram geometric figure. For many of his students, the enneagram remained a challenging symbol, never fully explained. While similarities to other figures have been noted, Gurdjieff is generally credited with introducing this specific enneagram figure to the public, and its true source is said to have been known only to him. Later, others, notably Oscar Ichazo and Claudio Naranjo, developed the Enneagram of Personality for personality analysis, an application largely distinct from Gurdjieff's original teaching or his explanations of the enneagram.

4. Methods and Practice

Gurdjieff employed a variety of methods and materials to facilitate self-observation and conscious development among his pupils, aiming to "put a spanner in the works" of their mechanical existence and foster a connection between mind and body.

4.1. Movements and Sacred Dances

The "Movements," also known as sacred dances, were a significant and integral component of Gurdjieff's teaching. Gurdjieff sometimes referred to himself as a "teacher of dancing" and initially gained public notice for his attempts to stage a ballet in Moscow called Struggle of the Magicians.

These choreographed exercises were designed to develop self-awareness and coordination between mind and body. Gurdjieff explained their purpose: "To each position of the body corresponds a certain inner state and, on the other hand, to each inner state corresponds a certain posture. A man, in his life, has a certain number of habitual postures and he passes from one to another without stopping at those between. Taking new, unaccustomed postures enables you to observe yourself inside differently from the way you usually do in ordinary conditions." The Movements required the integration of independent movements of multiple body parts and the harmonization of intellectual and physical functions, serving as a unique art form and a challenge for harmonious psychophysical development.

Films of Movements demonstrations are occasionally shown privately by Gurdjieff Foundations, and some examples are featured in a scene in the Peter Brook film Meetings with Remarkable Men. The dancers typically arrange themselves in six columns, corresponding to the numerical sequence of the Enneagram (142857).

4.2. Music

Gurdjieff's musical compositions, particularly his collaborations with Russian-born composer Thomas de Hartmann, are a notable part of his legacy. His music is generally divided into three distinct periods:

1. **First Period:** Early music, including pieces from the ballet Struggle of the Magicians and music for early movements, dating to around 1918.

2. **Second Period (Gurdjieff-de Hartmann music):** Composed in the mid-1920s, this is the most widely known period. Gurdjieff would indicate melodies by playing with one finger on the piano or whistling, and de Hartmann would develop them, with Gurdjieff adding new parts. This rich repertoire draws influences from Caucasian and Central Asian folk and religious music, Russian Orthodox liturgical music, and other sources. Much of this music was composed and first heard in the salon at the Prieuré. Four volumes of this piano repertoire have been published by Schott, leading to numerous new recordings, including orchestral versions prepared for the Movements demonstrations of 1923-1924. Solo piano versions of these works have been recorded by artists such as Cecil Lytle, Keith Jarrett, and Frederic Chiu.

3. **Last Musical Period:** This refers to the improvised harmonium music that often followed the dinners Gurdjieff hosted at his Paris apartment during the World War II occupation and immediate post-war years until his death in 1949.

In total, Gurdjieff, in collaboration with de Hartmann, composed approximately 200 pieces. In May 2010, 38 minutes of unreleased solo piano music on acetate was acquired from the estate of Dushka Howarth. In 2009, pianist Elan Sicroff released Laudamus: The Music of Georges Ivanovitch Gurdjieff and Thomas de Hartmann, featuring a selection of their collaborations. Alessandra Celletti also released "Hidden Sources" in 1998 with 18 tracks by Gurdjieff/de Hartmann.

The English concert pianist and composer Helen Perkin (later Helen Adie), a pupil of Ouspensky, visited Gurdjieff in Paris after the war. She and her husband, George Adie, emigrated to Australia in 1965 and established the Gurdjieff Society of Newport. Recordings of her performing de Hartmann's music have been issued on CD. She was also a Movements teacher and composed music for the Movements, some of which has been published and privately circulated.

4.3. Spiritual Practice

Gurdjieff's spiritual practice was designed to break habitual patterns and awaken awareness, moving beyond purely intellectual or devotional approaches. He believed that traditional methods of self-knowledge through pain (Fakir), devotion (Monk), or study (Yogi) were insufficient on their own. Instead, he advocated "the way of the sly man" as a shortcut to inner development, which might otherwise take years without real outcome. This approach shares parallels with Zen Buddhism, where teachers employed unorthodox methods to induce insight.

Gurdjieff used various exercises to prompt self-observation in his students. A notable example is the "Stop" exercise, where he would suddenly call out "Stop!" and students were required to immediately freeze in their current posture, both physically and mentally, to observe their inner state. Other "shocks" were always possible at any moment to awaken his pupils from constant daydreaming.

His teachings were transmitted through diverse means, including group work, physical labor, crafts, idea exchanges, arts, music, movement, dance, and adventures in nature. These varied methods aimed to disrupt mechanical behavior and foster a connection between mind and body, allowing individuals to transcend their acted-upon self and ascend from mere personality to self-actualizing essence. In Russia, his teaching was confined to a small circle, but in Paris and North America, he gave numerous public demonstrations.

5. Writings

Gurdjieff's literary contributions primarily consist of a trilogy known as All and Everything, along with collections of his talks and other works.

5.1. Major Works

Gurdjieff's magnum opus is the All and Everything trilogy, which he considered his "legominism"-a means of transmitting information about long-past events through initiates. The trilogy comprises:

- Beelzebub's Tales to His Grandson (First Series): Published posthumously in 1950, this lengthy allegorical work (over 1200 pages) recounts Beelzebub's explanations to his grandson about Earth's beings and universal laws, serving as a platform for Gurdjieff's philosophy. Gurdjieff advised readers to read each of the three series three times in sequence to form an impartial judgment. A controversial redaction was published in 1992 by some followers.

- Meetings with Remarkable Men (Second Series): Published in 1963, this work is presented as a memoir of his early years but includes "Arabian Nights" embellishments and allegorical statements.

- Life Is Real Only Then, When 'I Am' (Third Series): Published in 1978 for private distribution, this unfinished work offers an intimate account of Gurdjieff's inner struggles in his later years and includes transcripts of some of his lectures.

Another significant work is Views from the Real World: Early Talks in Moscow, Essentuki, Tiflis, Berlin, London, Paris, New York, and Chicago, as recollected by his pupils, a collection of his early talks compiled by his student and personal secretary, Olga de Hartmann, and published in 1973.

Other published works by Gurdjieff include:

- The Herald of Coming Good: First Appeal to Contemporary Humanity (1933)

- Transcripts of Gurdjieff's Meetings 1941-1946 (2009)

- The Struggle of the Magicians: Scenario of the Ballet (2014)

- In Search of Being: The Fourth Way to Consciousness (2012)

5.2. Pupils' Writings

Gurdjieff's views were initially disseminated and interpreted through the writings of his pupils. The most widely known and read of these is P. D. Ouspensky's In Search of the Miraculous: Fragments of an Unknown Teaching, which is considered a crucial introductory text to the teaching. However, some prefer Gurdjieff's own books as primary texts.

Numerous anecdotal accounts of time spent with Gurdjieff were published by his close followers, including Charles Stanley Nott, Thomas and Olga de Hartmann, Fritz Peters, René Daumal, John G. Bennett, Maurice Nicoll, Margaret Anderson, and Louis Pauwels.

The feature film Meetings with Remarkable Men (1979), loosely based on Gurdjieff's book of the same name, was co-written by Jeanne de Salzmann and Peter Brook, directed by Brook, and stars Dragan Maksimovic, Terence Stamp, and Athol Fugard. The film notably concludes with performances of Gurdjieff's dances.

6. Reception and Influence

Gurdjieff's teachings and activities have elicited diverse opinions, ranging from profound admiration to sharp criticism. His influence has extended across various fields, inspiring numerous individuals and organizations.

6.1. Ideological Influence

Gurdjieff had a significant impact on various fields, including arts, literature, psychology, and alternative spiritual movements in the 20th and 21st centuries. His ideas provided a psychology and cosmology that offered insights beyond established science. Notable figures influenced by Gurdjieff include artists, writers, and thinkers such as Walter Inglis Anderson, Peter Brook, Kate Bush, Darby Crash, Muriel Draper, Robert Fripp, Keith Jarrett, Timothy Leary, Katherine Mansfield, Dennis Lewis, James Moore, A. R. Orage, P. D. Ouspensky, Maurice Nicoll, Louis Pauwels, Robert S. de Ropp, René Barjavel, Rene Daumal, George Russell, David Sylvian, Jean Toomer, Jeremy Lane, Therion, P. L. Travers, Alan Watts, Minor White, Colin Wilson, Robert Anton Wilson, Frank Lloyd Wright, John Zorn, and Franco Battiato.

His teachings gave new life and practical form to ancient Eastern and Western wisdom. The Socratic and Platonic emphasis on "know thyself" is echoed in Gurdjieff's practice of self-observation. His concepts of self-discipline and restraint reflect Stoic teachings. The Hindu and Buddhist notion of attachment reappears in his teaching as "identification."

The Fourth Way Enneagram geometric figure, introduced by Gurdjieff, has become particularly prominent. While its origins are debated, Gurdjieff was the first to make it publicly known. Later, the enneagram figure was adapted for personality analysis, notably in the Enneagram of Personality developed by Oscar Ichazo and Claudio Naranjo, though most aspects of this application are not directly connected to Gurdjieff's original teaching.

6.2. Key Pupils

Many of Gurdjieff's students were instrumental in transmitting and developing his teachings.

- P. D. Ouspensky (1878-1947): A Russian journalist, author, and philosopher, Ouspensky met Gurdjieff in 1915 and studied with him for five years. He later formed his own independent groups in London in 1921 and became a key figure in disseminating Gurdjieff's ideas through his book In Search of the Miraculous, which remains the most widely read account of Gurdjieff's early group experiments.

- Thomas de Hartmann (1885-1956): A Russian composer, he and his wife Olga met Gurdjieff in 1916 and remained close students until 1929. They lived at Gurdjieff's Institute near Paris, where de Hartmann transcribed and co-wrote much of the music used for the Movements, collaborating on hundreds of piano pieces.

- Olga de Hartmann (1885-1979): Gurdjieff's personal secretary during the Prieuré years, she took most of the original dictations of his writings and authenticated his early talks in Views from the Real World. Her memoir, Our Life with Mr Gurdjieff, details their years with him.

- Jeanne de Salzmann (1889-1990): A dancer and Dalcroze Eurythmics teacher, she and her husband Alexander met Gurdjieff in Tiflis in 1919. She was crucial in transmitting Gurdjieff's choreographed movement exercises and institutionalizing his teachings through the Gurdjieff Foundation and other groups established in 1953.

- John G. Bennett (1897-1974): A British intelligence officer, polyglot, technologist, author, and teacher, Bennett met Gurdjieff in Istanbul in 1920. He was a pupil of Ouspensky for many years and, after discovering Gurdjieff was still alive, became a frequent visitor in Paris in 1949. His books include Witness: the Autobiography of John Bennett and Gurdjieff: Making a New World.

- Alfred Richard Orage (1873-1934): An influential British editor of New Age magazine, Orage met Gurdjieff in London in 1922. He sold his magazine and moved to the Prieuré, later leading the institute's New York branch. He was responsible for editing the English typescripts of Beelzebub's Tales and Meetings with Remarkable Men as Gurdjieff's assistant.

- Maurice Nicoll (1884-1953): A Harley Street psychiatrist and Carl Jung's delegate in London, Nicoll attended Ouspensky's talks and spent nearly a year at the Prieuré. He later started his own Fourth Way groups in England and is known for his six-volume Psychological Commentaries on the Teaching of Gurdjieff and Ouspensky.

- Willem Nyland (1890-1975): A Dutch-American chemist, Nyland met Gurdjieff in 1924 and was a charter member of the New York branch of Gurdjieff's Institute. He later established an independent group in Warwick, New York, where he made extensive audio recordings of his meetings.

- Jane Heap (1883-1964): An American writer, editor, artist, and publisher, Heap met Gurdjieff in New York in 1924 and established a study group in Greenwich Village. She later moved to Paris to study at the Institute and was sent by Gurdjieff to lead a group in London until her death. Her Paris group became Gurdjieff's 'Rope' group.

- Kenneth Macfarlane Walker (1882-1966): A prominent British surgeon and prolific author, Walker was a member of Ouspensky's London group for decades. After Ouspensky's death, he visited Gurdjieff in Paris and wrote early informed accounts of Gurdjieff's ideas, including Venture with Ideas and A Study of Gurdjieff's Teaching.

- Henry John Sinclair, 2nd Baron Pentland (1907-1984): A pupil of Ouspensky, Pentland visited Gurdjieff regularly in Paris in 1949. He was appointed President of the Gurdjieff Foundation of America by Jeanne de Salzmann in 1953 and remained President of the US Foundation branches until his death.

6.3. Criticism and Controversy

Opinions on Gurdjieff's writings and activities are divided. While sympathizers consider him a charismatic master who introduced new knowledge and a profound psychology and cosmology to Western culture, some critics assert he was a charlatan with a large ego and a constant need for self-glorification. Osho described Gurdjieff as one of the most significant spiritual masters of his age.

One point of criticism is Gurdjieff's insistence that most people are "asleep" in a state resembling "hypnotic sleep." He stated that a pious, good, and moral person was no more "spiritually developed" than any other, all being equally "asleep." This perspective, which some interpreted as a total disregard for the value of mainstream religion, philanthropic work, or conventional morality, drew criticism from within those traditions. Gurdjieff, in Beelzebub's Tales, expressed reverence for the founders of mainstream religions but contempt for what successive generations had made of their teachings, using terms like "orthodoxhydooraki" and "heterodoxhydooraki" (orthodox fools and heterodox fools).

Henry Miller approved of Gurdjieff not considering himself holy but, after writing an introduction to Fritz Peters' book Boyhood with Gurdjieff, he questioned the idea of a "harmonious life" that Gurdjieff's institute aimed for.

Louis Pauwels, author of Monsieur Gurdjieff (1954), recounted a negative personal experience with the Gurdjieff work, stating that after two years of exercises that both "enlightened and burned" him, he ended up in a hospital with severe physical and mental distress, though he attributed it to his own fault.

The split between Gurdjieff and P. D. Ouspensky also led to differing interpretations. Ouspensky, who taught independently, referred to Gurdjieff's teachings as "the system" but claimed it originated from hidden "schools" and that Gurdjieff was not always a suitable receiver of the knowledge. This view influenced later figures like Helen Palmer, who, in her work on the Enneagram of Personality, claimed that Gurdjieff was "unqualified" to transmit the deeper aspects of the enneagram, suggesting it belonged to an ancient esoteric tradition. Although Ouspensky later acknowledged the limitations of "the system," his dream of contact with an invisible "school" persisted, influencing students like Rodney Collin.

6.4. Legacy and Organizations

The enduring legacy of Gurdjieff's teachings is evident in the numerous groups and organizations that continue to function worldwide, exploring and practicing his ideas. After his death, the Gurdjieff Foundation in Paris was established in the early 1950s by his close pupil Jeanne de Salzmann, in cooperation with other direct pupils. She led the foundation until her death in 1990, followed by her son Michel de Salzmann until his death in 2001.

The International Association of the Gurdjieff Foundations comprises key institutions such as the Institut Gurdjieff in France, The Gurdjieff Foundation in the USA, The Gurdjieff Society in the UK, and the Gurdjieff Foundation in Venezuela.

Beyond these official foundations, other pupils of Gurdjieff formed independent groups. Willem Nyland, a close student and original trustee of The Gurdjieff Foundation of New York, left to form his own groups in the early 1960s. Jane Heap was sent by Gurdjieff to London, where she led groups until her death in 1964. Louise Goepfert March, a pupil since 1929, started her own groups in 1957. Independent thriving groups were also established and initially led by John G. Bennett and A. L. Staveley near Portland, Oregon. These diverse organizations and groups continue to explore and transmit Gurdjieff's unique methods for self-development and the awakening of consciousness.