1. Overview

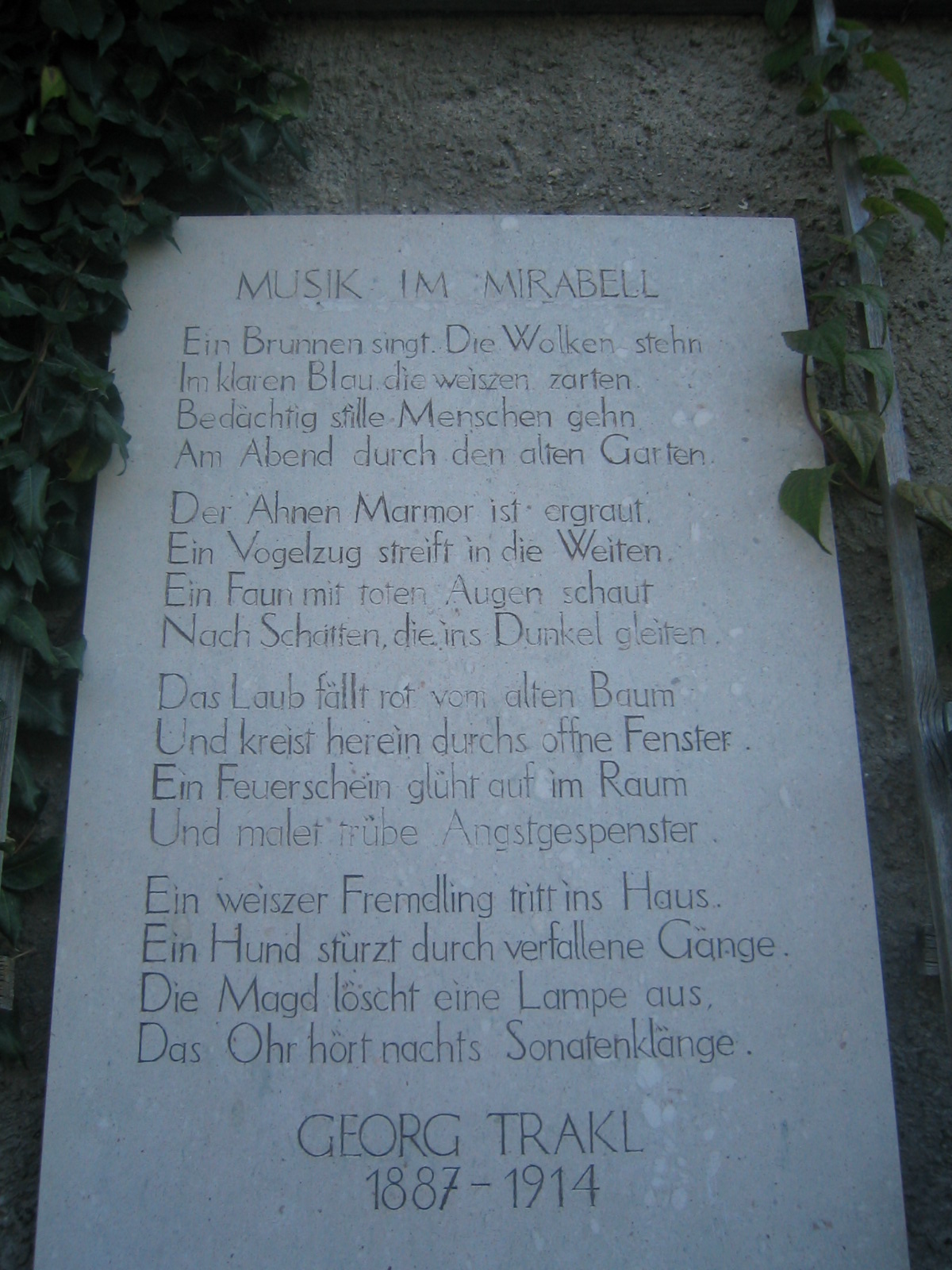

Georg Trakl, born on February 3, 1887, and passing on November 3, 1914, was an influential Austrian poet, widely regarded as one of the most significant figures of Expressionism in German-speaking literature. His brief yet impactful life, marked by profound melancholy, drug addiction, and a complex family background, deeply informed his poetic output. Trakl's work is characterized by its condensed expression, distinctive use of color, and Symbolist tendencies, often exploring themes of decay, suffering, silence, and the evening. He is particularly known for his poem "Grodek", written shortly before his death from a cocaine overdose during World War I. His poetry, though challenging, has left a lasting legacy, influencing numerous artists, philosophers, and composers, and continues to be studied for its unique contribution to modern literature.

2. Life

Georg Trakl's life was a tumultuous journey marked by personal struggles and a deep engagement with the artistic currents of his time.

2.1. Early Life and Family Background

Georg Trakl was born in Salzburg, Austria-Hungary, on February 3, 1887, as the fourth of six children to Tobias Trakl and Maria Catharina Halik. His father, Tobias Trakl (born June 11, 1837, in Ödenburg/Sopron, Hungary; died 1910), was a prosperous hardware dealer of Hungarian (Magyar) descent. His mother, Maria Catharina Halik (born May 17, 1852, in Wiener Neustadt; died 1925), was of partly Czech origin. Maria Catharina was deeply interested in art and music, preferring collecting antique art objects over traditional household duties. She taught Trakl to play the piano, and he developed a fondness for the music of Chopin, Liszt, and Wagner. She also struggled with substance use disorder, which impacted the family environment.

Trakl's education was largely entrusted to a French "gouvernante," who introduced him to French language and literature at an early age. He had a particularly complex and intense relationship with his younger sister, Margarethe Trakl, who was a musical prodigy and a talented pianist. They shared deep artistic endeavors, and some of Trakl's poems allude to an incestuous relationship between them, though explicit evidence remains unconfirmed as family correspondence was reportedly destroyed after their deaths.

2.2. Education and Early Activities

Despite his parents being Protestants, Trakl attended a Catholic elementary school, though he received supplementary religious instruction at a Protestant school. In 1897, he matriculated at the Salzburg Staatsgymnasium, where he encountered significant academic difficulties, particularly in Latin, Greek, and mathematics. These struggles led to him repeating a year, and he eventually left the gymnasium in 1905 without obtaining his Matura (secondary school leaving certificate).

Trakl began writing poetry around the age of 13. During his student years, he formed a literary circle called "Minerva" with his classmates. He was deeply influenced by Symbolist poets, especially Charles Baudelaire (whose collection Les Fleurs du mal he admired), as well as by writers and philosophers such as Fyodor Dostoevsky, Friedrich Nietzsche, Friedrich Hölderlin, and Hugo von Hofmannsthal. Around this time, he also began to experiment with narcotic drugs, an indulgence that deepened due to his academic failures and growing despair. He attempted to write plays, but his two short dramatic works, All Souls' Day (Totentag) and Fata Morgana, were unsuccessful and later destroyed by Trakl himself. From May to December 1906, Trakl published four prose pieces in the feuilleton sections of two Salzburg newspapers. These early prose works, including "Traumland" (Dreamland), which features a young man falling in love with his dying cousin, already contained themes and settings that would recur in his mature poetry.

2.3. Pharmacy Studies and Professional Life

After leaving high school, Trakl decided to pursue a career in pharmacy, which he believed would offer him a stable profession and, inadvertently, easier access to drugs such as morphine and cocaine. He undertook a three-year apprenticeship as a pharmacist. In 1908, he moved to Vienna to continue his pharmacy studies at the University of Vienna. During his time in Vienna, he connected with local artists and bohemian figures who would later assist him in publishing some of his poems. It was also during this period that he encountered the poetry of Arthur Rimbaud, which profoundly impacted him.

In 1910, Trakl successfully passed his pharmacy certificate examination, coincidentally around the time of his father's death. Following this, he enlisted in the Austro-Hungarian Army for a year of military service. His subsequent attempt to return to civilian life in Salzburg proved unsuccessful, leading him to re-enlist in the army. He was assigned as a pharmacist at a military hospital in Innsbruck.

2.4. Literary Career and Patronage

While stationed in Innsbruck, Trakl became acquainted with a vibrant group of avant-garde artists and intellectuals associated with Der Brenner, a highly respected literary journal. This journal was notable for initiating a revival of Kierkegaard's philosophy in German-speaking countries. Ludwig von Ficker, the editor of Der Brenner and son of the historian Julius von Ficker, became a crucial patron for Trakl. Ficker regularly published Trakl's poems in his journal and actively worked to find a publisher for a collection of his works.

These efforts culminated in the publication of Trakl's first and only collection released during his lifetime, Gedichte (Poems), which was published by Kurt Wolff in Leipzig in the summer of 1913. A second collection, Sebastian im Traum (Sebastian in the Dream), was also prepared for publication but its release was delayed by the outbreak of World War I, meaning Trakl never saw the completed book.

Ficker also introduced Trakl to the philosopher Ludwig Wittgenstein. Wittgenstein, who had inherited a substantial fortune, anonymously provided Trakl with a generous stipend of 20,000 Krone (a significant sum compared to Trakl's annual civil servant salary of 600 Krone) through Ficker. This financial support was intended to allow Trakl to dedicate himself entirely to his writing. Wittgenstein also anonymously supported other artists like Rainer Maria Rilke, Oskar Kokoschka, and Adolf Loos. Despite these literary successes and patronage, Trakl struggled to maintain stable employment, moving between various positions as a pharmacist and civil servant in Salzburg and Innsbruck, none of which lasted long. His personal life was further complicated by the news that his beloved sister Margarethe, who had recently married, suffered a stillbirth and was critically ill, though she eventually recovered.

3. World War I and Death

At the onset of World War I, seeking an escape from his increasingly desperate civilian life, Trakl voluntarily re-enlisted in the Austro-Hungarian Army. He was deployed to Galicia (a historical region now divided between Ukraine and Poland) as a medical officer candidate, serving as a pharmacist's assistant on the Eastern Front.

During the Battle of Gródek in autumn 1914, fought near Gródek, Trakl faced immense psychological strain. He was tasked with caring for approximately ninety severely wounded soldiers without adequate medical supplies. The horrific scenes he witnessed-his comrades bleeding and groaning inside, and enemy soldiers hanged as spies outside-overwhelmed him. Under this severe emotional duress, he attempted to commit suicide with his pistol, but was prevented by his fellow soldiers.

Following this incident, Trakl was confined to a military hospital in Kraków and placed under close observation. His depression worsened considerably. He wrote to his patron, Ludwig von Ficker, seeking advice and support, expressing a profound sense of despair. Ficker, realizing that his letters had not been reaching Trakl on the front lines, immediately tried to encourage him and arranged for Wittgenstein, who was also serving in the Kraków region, to visit Trakl. Unfortunately, Wittgenstein was away on another assignment when Ficker's request arrived. Upon his return, Wittgenstein received a letter from Trakl himself, expressing a strong desire to meet. Wittgenstein, who also struggled with loneliness and melancholia, was eager to converse with the gifted poet. However, when he arrived at the hospital, it was three days after Trakl had died. Georg Trakl succumbed to a cocaine overdose on November 3, 1914, at the age of 27.

He was initially buried at Kraków's Rakowicki Cemetery on November 6, 1914. Years later, on October 7, 1925, through the persistent efforts of Ludwig von Ficker, Trakl's remains were exhumed and reinterred in the municipal cemetery of Innsbruck-Mühlau, where they now rest beside Ficker's grave.

4. Works and Themes

Georg Trakl's poetic output, though relatively small due to his short life, is highly distinctive and profoundly influential within the Expressionist movement.

4.1. Major Works

Trakl's primary published poetry collections include:

- Gedichte (Poems), published in 1913, was the only collection released during his lifetime.

- Sebastian im Traum (Sebastian in the Dream), published posthumously in 1915.

- Der Herbst des Einsamen (The Autumn of The Lonely One), published in 1920.

- Gesang des Abgeschiedenen (Song of the Departed), published in 1933.

His poem "Grodek" is particularly notable, having been written shortly before his death and reflecting his harrowing experiences on the Eastern Front during World War I.

4.2. Literary Style and Motifs

Trakl's poetry is a prime example of Expressionism, characterized by its compressed language and intense emotionality. He also shows strong Symbolist tendencies, particularly influenced by poets like Arthur Rimbaud and Charles Baudelaire. A distinctive feature of his style is his unique deployment of color words, which are often used to evoke specific moods and sensations rather than merely describe.

Recurring motifs in his work include:

- Evening: Many of his poems are set in the evening or use it as a central motif, contributing to a pervasive sense of melancholy and twilight.

- Silence: Silence is a frequent theme, especially in his later poems, which often feature the "silent dead" who are unable to express themselves, reflecting a profound sense of isolation and despair.

- Decay and Suffering: His poetry frequently explores themes of physical and spiritual decay, suffering, and the dissolution of the self, often reflecting a deep sense of Weltschmerz (world-weariness).

- Nature: Nature often appears as a backdrop for human suffering, imbued with a sense of impending doom or desolate beauty.

While his earliest poems were more philosophical, the majority of his mature works are deeply rooted in the real world, albeit seen through a distorted, often nightmarish lens. His work is known for its dark, often unsettling imagery and its exploration of the human psyche's darker aspects.

5. Critical Reception and Legacy

Trakl's poetry, despite its challenging nature, has garnered significant critical acclaim and exerted a lasting influence on subsequent artistic and philosophical thought.

5.1. Artistic and Philosophical Influence

Georg Trakl's works have been highly regarded and deeply appreciated by prominent thinkers and artists. Philosophers such as Martin Heidegger and poets like Rainer Maria Rilke held his poetry in high esteem and were profoundly influenced by it. His unique voice and innovative use of language contributed significantly to the development of modern German literature, particularly within the Expressionist movement. Trakl's ability to condense complex emotions and imagery into stark, evocative verses resonated with many who sought new forms of artistic expression in the early 20th century. His work continues to be a subject of intense academic study and artistic interpretation, highlighting his enduring impact on literature and intellectual discourse.

5.2. Criticism and Controversy

Trakl's life was marked by significant personal struggles that have also become subjects of critical discussion. His long-standing battle with drug addiction, particularly his reliance on morphine and cocaine, is frequently addressed in analyses of his work, often seen as both a coping mechanism for his profound psychological distress and a contributing factor to his early death.

Another controversial aspect is the alleged incestuous relationship with his sister, Margarethe. While Trakl's poems contain allusions to an intense and possibly illicit bond, concrete evidence remains elusive. After the deaths of both Georg and Margarethe (who also died by suicide in 1917), their family reportedly destroyed their correspondence, leaving the nature of their relationship open to speculation and interpretation by biographers and literary critics. These biographical elements, while controversial, are often considered integral to understanding the dark and tormented themes prevalent in his poetry.

6. Adaptations and Influences in Popular Culture

Georg Trakl's life and poetry have inspired a diverse range of adaptations across various artistic mediums, reflecting the enduring power and resonance of his work.

6.1. Musical Adaptations

Numerous composers have set Trakl's poems to music or drawn inspiration from his life and themes:

- Paul Hindemith: Die Junge Magd - Six Poems by Georg Trakl for alto voice with flute, clarinet, and string quartet, opus 23 No.2.

- Anton Webern: 6 Lieder nach Gedichten von Georg Trakl, Op. 14.

- Peter Maxwell Davies: Revelation and Fall, a monodrama for soprano and instrumental ensemble, composed in 1966.

- Wilhelm Killmayer: Set several of Trakl's poems in two song cycles, Trakl-LiederGerman (1993) and Schweigen und KindheitGerman (1996).

- Heinz Winbeck: Symphony No. 3 Grodek for alto, speaker, and orchestra (1988).

- Hans Werner Henze: Sebastian im Traum, an orchestral composition from 2004 based on Trakl's work.

- David Tukhmanov: The Russian composer wrote a triptych for mezzo-soprano and piano titled Dream of Sebastian, or Saint Night, based on Trakl's poems. It premiered in 2007.

- Henry Breneman Stewart: Kristalliner Schrei, a 2014 setting of three poems from Gedichte for mezzo-soprano and string quartet.

- Denise Roger: The French composer (1924-2005) used Trakl's texts in her songs "Rondel" and "Gesang einer gefangenen Amsel."

- Philippe Manoury: Trakl Gedichte, published by Éditions Durand.

- Thea Musgrave: Wild Winter: Lament V.

- Jute Gyte: The experimental black metal artist used the entirety of Trakl's "Helian" on his 2021 album of the same name.

- Dead Eyed Sleeper: The band used Trakl's poem Menschheit as lyrics for their song of the same name on their 2016 album Gomorrh.

6.2. Dance Adaptations

Trakl's poetry has also been interpreted through choreographic works:

- Angela Kaiser: "Silence Spoken: ...quiet answers to dark questions" (2015), an intersemiotic translation of five of Trakl's poems into dance.

6.3. Film Adaptations

Films have also explored Trakl's life and drawn inspiration from his work:

- Tabu - Es ist die Seele ein Fremdes auf Erden (released May 31, 2012), a film related to his life.

7. Bibliography and Further Reading

This section provides a comprehensive overview of Georg Trakl's published works, their translations, and significant critical studies, along with online resources for further exploration.

7.1. Original Works

- Gedichte (Poems), 1913

- Sebastian im Traum (Sebastian in the Dream), 1915

- Der Herbst des Einsamen (The Autumn of The Lonely One), 1920

- Gesang des Abgeschiedenen (Song of the Departed), 1933

7.2. Translated Works

Trakl's poetry has been translated into numerous languages, including English, Japanese, and Korean.

English Translations:

- Decline: 12 Poems, translated by Michael Hamburger and Guido Morris, Latin Press, 1952.

- Twenty Poems of George Trakl, translated by James Wright and Robert Bly, The Sixties Press, 1961.

- Selected Poems, edited by Christopher Middleton, translated by Robert Grenier et al., Jonathan Cape, 1968.

- Georg Trakl: Poems, translated by Lucia Getsi, Mundus Artium Press, 1973.

- Georg Trakl: A Profile, edited by Frank Graziano, Logbridge-Rhodes, 1983.

- Song of the West: Selected Poems, translated by Robert Firmage, North Point Press, 1988.

- The Golden Goblet: Selected Poems of Georg Trakl, 1887-1914, translated by Jamshid Shirani and A. Maziar, Ibex Publishers, 1994.

- Autumn Sonata: Selected Poems of Georg Trakl, translated by Daniel Simko, Asphodel Press, 1998.

- Poems and Prose, Bilingual edition, translated by Alexander Stillmark, Libris, 2001 (re-edition by Northwestern University Press, 2005).

- To the Silenced: Selected Poems, translated by Will Stone, Arc Publications, 2006.

- In an Abandoned Room: Selected Poems by Georg Trakl, translated by Daniele Pantano, Erbacce Press, 2008.

- The Last Gold of Expired Stars: Complete Poems 1908 - 1914, translated by Jim Doss and Werner Schmitt, Loch Raven Press, 2011.

- Song of the Departed: Selected Poems of George Trakl, translated by Robert Firmage, Copper Canyon Press, 2012.

- "Uncommon Poems and Versions by Georg Trakl", translated by James Reidel, Mudlark No. 53, 2014.

- Poems, translated by James Reidel, Seagull Books, 2015.

- Sebastian Dreaming, translated by James Reidel, Seagull Books, 2016.

- A Skeleton Plays Violin, translated by James Reidel, Seagull Books, 2017.

- Autumnal Elegies: Complete Poetry, translated by Michael Jarvie, 2019.

- Surrender to Night: The Collected Poems of Georg Trakl, translated by Will Stone, Pushkin Collection, 2019.

- Collected Poems, translated by James Reidel, Seagull Books, 2019.

- Georg Trakl: The Damned, translated by Daniele Pantano, Broken Sleep Books, 2023.

Japanese Translations:

- Georg Trakl Shishu Tairyaku (Georg Trakl Poetry Collection, Bilingual), translated and annotated by Norbert Holmuth, Ryo Kurisaki, and Natsuki Takita, Dogakusha, 1967.

- Trakl Shishu (Trakl Poetry Collection), translated by Toshio Hirai, Chikuma Sosho, 1967 (new edition 1985).

- Gensho e no Tabidachi Shishu (Journey to the Origin: Poetry Collection), translated by Takehiko Hata, Kokubunsha, 1968 (Pipou Sosho).

- Trakl Shishu (Trakl Poetry Collection), translated by Hirotsugu Yoshimura, Yayoi Shobo, 1968 (Sekai no Shi).

- Sekai Shijin Zenshu Dai 22 (Complete Works of World Poets Vol. 22), Trakl (translated by Kenichi Takamoto), Shinchosha, 1969.

- Doitsu Hyogenshugi 1 (Hyogenshugi no Shi) (German Expressionism 1 (Expressionist Poetry)), Trakl (translated by Michio Naito), Kawade Shobo Shinsha, 1971.

- Trakl Zenshishu (Complete Poems of Trakl), translated by Asako Nakamura, Seidosha, 1983.

- Trakl Zenshu (Complete Works of Trakl), translated by Asako Nakamura, Seidosha, 1987 (new editions 1997, 2015).

- Trakl Shishu (Trakl Poetry Collection), compiled and translated by Natsuki Takita, Ozawa Shoten, 1994 (Sosho: 20 Seiki no Shijin).

- Rüdiger Görner, Georg Trakl: Sei no Danagai o Ayunda Shijin (Georg Trakl: The Poet Who Walked the Precipice of Life), translated by Asako Nakamura, Seidosha, 2017.

Korean Translations:

- Mongsan gwa Chakran (Dream and Delirium), translated by Park Sul, ITTA, April 20, 2020 (complete translation).

- Pureun Sungan, Geomeun Yegam (Blue Moment, Black Premonition), translated by Kim Jae-hyuk, Minumsa, August 30, 2020 (selected translation).

7.3. Critical Studies

- Lindenberger, Herbert. Georg Trakl. New York: Twayne, 1971.

- Leiva-Merikakis, Erasmo. Blossoming Thorn: Georg Trakl's Poetry of Atonement, Bucknell University Press, 1987.

- Sharp, Francis Michael. The Poet's Madness: A Reading of Georg Trakl. Ithaca: Cornell UP, 1981.

- Millington, Richard. Snow from Broken Eyes: Cocaine in the Lives and Works of Three Expressionist Poets, Peter Lang AG, 2012.

- Millington, Richard. The Gentle Apocalypse: Truth and Meaning in the Poetry of Georg Trakl, Camden House, 2020.

- Schliep, Hans Joachim. on the Table Bread and wine- poetry and Religion in the works of Georg Trakl, Lambert Academic Publishing (LAP), 2020.

- Cho, Doo-hwan. Georg Trakl, Konkuk University Press, 1996.

- Brown, Peter. Saekdareun Munhaksa (A Different Literary History), translated by Hong Yi-jeong, Joeun Chaek Mandeulgi, 2008.

- Görner, Rüdiger. Georg Trakl: Sein Leben in Bildern und Texten (Georg Trakl: His Life in Pictures and Texts), translated by Asako Nakamura, Seidosha, 2017.

7.4. Online Resources

- [http://redyucca.wordpress.com/category/georg-trakl/ Red Yucca - German Poetry in Translation] (translated by Eric Plattner)

- [http://leoyankevich.com/archives/22 Translation of Trakl Poem]

- [http://poemhunter.com/ebooks/redir.asp?ebook=53381&filename=georg_trakl_2012_2.pdf Translations of Trakl on PoemHunter - PDF]

- [https://web.archive.org/web/20050131131342/http://dreamsongs.com/NewFiles/Trakl.pdf Twenty Poems, trans. by James Wright and Robert Bly] - PDF file of a 1961 translation.

- [http://www.literaturnische.de/Trakl/english/index-trakl-e.htm The Complete Writings of Georg Trakl in English] - translations by Wersch and Jim Doss.

- [http://www.lieder.net/lieder/get_author_texts.html?AuthorId=2828] Trakl texts set to music, translated by Bertram Kottmann.

- [https://royalscottfottish.files.wordpress.com/2015/11/bananartista_sulla-tomba-di-georg-trakl-innsbruck.jpg?w=768 Photo 1] and [http://www.mironde.com/litterata/wp-content/uploads/2015/12/151220Trakl8027.jpg Photo 2] of the graves of Ludwig von Ficker (left) and Georg Trakl (right) at the cemetery of Innsbruck-Mühlau.