1. Overview

Francisco José de Goya y Lucientes (Francisco José de Goya y Lucientesfɾanˈθisko xoˈse ðe ˈɣoʝa i luˈθjentesSpanish; March 30, 1746 - April 16, 1828) was a prominent Spanish Romantic painter and printmaker. He is widely regarded as the most significant Spanish artist of the late 18th and early 19th centuries, often described as the last of the Old Masters and the first of the moderns. His extensive body of work, encompassing paintings, drawings, and engravings, profoundly reflected the contemporary historical upheavals of his time and exerted a significant influence on subsequent generations of artists, including 19th- and 20th-century masters like Édouard Manet and Pablo Picasso. Goya served as a court painter to the Spanish Crown and meticulously documented the events of his era, transitioning from a classical approach to one that foreshadowed Impressionism. His innovative, subjective style and bold brushwork left a lasting legacy, with many of his major works housed in the Museo del Prado in Madrid.

2. Early Life and Education

Francisco José de Goya y Lucientes was born on March 30, 1746, in Fuendetodos, a village in the Aragon region of Spain, approximately 186 mile (300 km) from Madrid. He was the fourth of six children born to José Benito de Goya y Franque and Gracia de Lucientes y Salvador. His father, a gilder specializing in religious and decorative craftwork, was of Basque origin and the son of a notary. The family, considered lower middle-class, initially resided in his mother's family home, which, though modest, bore their family crest, reflecting their aspirations to nobility. Around 1749, Goya's family acquired a home in Zaragoza, the central city of Aragon, and relocated there.

While there are no definitive records, it is believed Goya attended the Escuelas Pías de San Antón, a school that offered free education. His schooling provided him with basic literacy and numeracy, along with some knowledge of the classics, though it was not considered particularly enlightening. During his time at school, Goya formed a close and enduring friendship with a fellow pupil, Martín Zapater. The 131 letters Goya wrote to Zapater between 1775 and Zapater's death in 1803 offer valuable insights into Goya's early years and his thoughts, which he rarely expressed publicly.

At the age of 14, Goya began his artistic training as an apprentice under the painter José Luzán y Martinez in Zaragoza. For four years, he honed his skills by copying existing works, but he later expressed a desire to "paint from my invention," indicating an early ambition for creative originality. Subsequently, he moved to Madrid to study with Anton Raphael Mengs, a prominent court painter favored by Spanish royalty. However, Goya's relationship with Mengs was strained, and his examinations were deemed unsatisfactory. Despite his talent, Goya was twice denied admission to the Real Academia de Bellas Artes de San Fernando in 1763 and 1766.

3. Visit to Italy and Early Career

Undeterred by his rejections from the Royal Academy and unable to secure a scholarship, Goya, following the long-standing tradition of European artists, traveled to Rome, Italy, at his own expense. Rome was then the cultural epicenter of Europe, offering access to prototypes of classical antiquity, a stark contrast to Spain, which lacked a cohesive artistic direction at the time. Details of his time in Italy are scarce and uncertain, with early biographers recounting colorful, though unverified, anecdotes such as his travels with bullfighters, work as a street acrobat, or involvement with a Russian diplomat, and even a romantic escapade involving a nun. During this visit, Goya is believed to have completed two surviving mythological paintings, *Sacrifice to Vesta* and *Sacrifice to Pan*, both dated 1771.

In 1771, Goya achieved his first notable recognition by winning second prize in a painting competition organized by the City of Parma. Later that year, he returned to Zaragoza and began receiving significant commissions. He painted sections of the cupolas of the Basilica of Our Lady of the Pillar (Santa Maria del Pilar), including the impressive Adoration of the Name of God. He also undertook a cycle of frescoes for the monastic church of the Charterhouse of Aula Dei and frescoes for the Sobradiel Palace. During this period, he studied with the Aragonese artist Francisco Bayeu y Subías, and his painting began to exhibit the delicate tonalities that would later become a hallmark of his style.

Goya developed a close friendship with Francisco Bayeu and, on July 25, 1773, married Bayeu's sister, Josefa Bayeu, whom he affectionately nicknamed "Pepa." Their first child, Antonio Juan Ramon Carlos, was born on August 29, 1774. Of their seven children, only one, a son named Javier, survived into adulthood.

4. Madrid and Court Painter

Goya's career gained significant momentum after his move to Madrid, largely facilitated by his brother-in-law, Francisco Bayeu y Subías, who was a member of the Real Academia de Bellas Artes de San Fernando since 1765 and director of the royal tapestry works from 1777. This connection helped Goya secure a commission for a series of tapestry cartoons for the Royal Tapestry Factory. Over a period of five years, from 1775 to 1792, Goya designed approximately 42 patterns. Many of these were used to decorate and insulate the stone walls of royal residences such as El Escorial and the Palacio Real del Pardo. While designing tapestries was not considered a highly prestigious or well-paid endeavor, Goya's cartoons, mostly in the popular Rococo style, served as a crucial platform for him to gain wider recognition. These works included pieces like Caza con reclamo (1775) and The Parasol (1777).

Goya, however, found the tapestry format limiting, as it did not allow him to fully explore complex color shifts, textures, or the impasto and glazing techniques he was increasingly applying to his painted works. He perceived the tapestries as commentaries on human types, fashion, and fads.

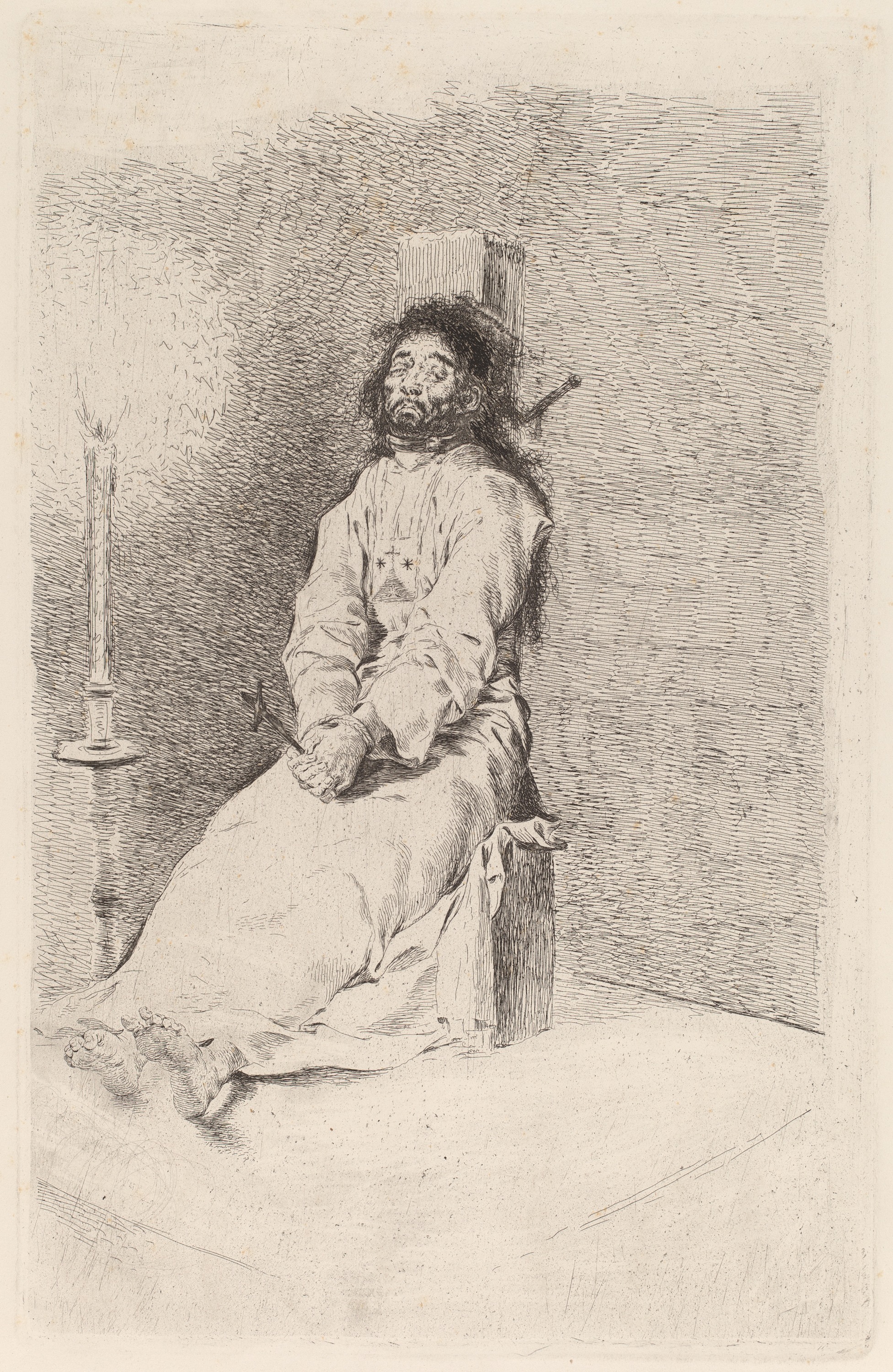

In addition to the tapestry cartoons, Goya also undertook a series of engravings, primarily copies of works by Old Masters such as Marcantonio Raimondi and Diego Velázquez. Although some contemporaries questioned his attempts to emulate Velázquez, Goya had unparalleled access to a wide range of the revered painter's works within the royal collection. Etching proved to be a medium that Goya mastered, allowing him to express the depths of his imagination and political convictions. His circa 1779 etching, The Garrotted Man (El agarrotadoSpanish), was his largest work to date and foreshadowed the dark themes of his later The Disasters of War series.

Goya's rising stature attracted jealousy from rivals, who sometimes used his bouts of illness against him. Some of his larger cartoons, measuring over 8 ft by 10 ft, had taken a toll on his physical strength. Resourcefully, Goya reframed his illness as a source of insight, claiming it enabled him to produce more personal and informal works. His talent was further recognized when a canvas he painted for the altar of the Church of San Francisco El Grande in Madrid led to his appointment as a member of the Royal Academy of Fine Art.

In 1783, Goya received a significant commission from the Count of Floridablanca, a close advisor to King Charles III. This commission, for a full-length portrait, marked Goya's entry into the highest echelons of Spanish society. He subsequently befriended King Charles III's half-brother, Infante Luis, and spent two summers painting portraits of the Infante and his family, including The Family of the Infante Don Luis (1784). Throughout the 1780s, Goya's circle of patrons expanded to include influential figures such as the Duke and Duchess of Osuna, whom he depicted with their children in Los duques de Osuna y sus hijos (1788). The Duchess of Osuna became one of his earliest and most significant patrons, and Goya's depiction of the Duke as a loving family man reflected the Enlightenment ideals embraced by the Spanish aristocracy.

In 1786, Goya was granted a salaried position as a painter to Charles III, solidifying his status. His ascent continued when, in 1789, he was appointed court painter to the new monarch, Charles IV of Spain. The following year, he achieved the highest rank for a Spanish court painter, Primer Pintor de Cámara (Prime Court Painter), with an annual salary of 50.00 K ESP and an additional 500 ESP for a coach.

As court painter, Goya produced numerous portraits of the royal family and nobility, including the king, queen, and Prime Minister Manuel de Godoy. His portraits are notable for their unflinching realism, often avoiding flattery. His masterpiece, Charles IV of Spain and His Family (1800-01), is considered a particularly stark and brutal assessment of the royal family. Modern interpretations often view it as satirical, revealing the perceived corruption behind Charles IV's rule, with Queen Louisa prominently placed at the center, believed to wield the real power. Goya himself can be seen in the background, looking out at the viewer, and the painting behind the family depicts Lot and his daughters, further echoing themes of corruption and decay. Goya also painted the Marchioness of Villafranca painting her husband, a work that captures the human essence of the sitter rather than just her noble status.

Goya received commissions from the highest ranks of the Spanish nobility, including Pedro Téllez-Girón, 9th Duke of Osuna and his wife María Josefa Pimentel, 12th Countess-Duchess of Benavente, José Álvarez de Toledo, Duke of Alba and his wife María del Pilar de Silva, and María Ana de Pontejos y Sandoval, Marchioness of Pontejos. In 1801, he painted Godoy in a commission commemorating the victory in the brief War of the Oranges against Portugal. Despite their friendship, Goya's 1801 portrait of Godoy is often seen as satirical. Even after Godoy's political downfall, he spoke warmly of Goya. Godoy is also widely believed to have commissioned La maja desnuda and played a role in the publication of the Caprichos.

His talent was further recognized when a canvas he painted for the altar of the Church of San Francisco El Grande in Madrid led to his appointment as a member of the Royal Academy of Fine Art.

5. Artistic Development and Key Periods

Goya's artistic style and thematic concerns underwent significant evolution throughout his career, marked by distinct phases influenced by personal experiences and historical events.

5.1. Middle Period (1793-1799)

A pivotal moment in Goya's life and art occurred between late 1792 and early 1793, when an undiagnosed illness left him completely deaf. This severe affliction, possibly a prolonged viral encephalitis, a series of miniature strokes, Ménière's disease, or even cumulative lead poisoning from his use of lead white pigments, caused a profound shift in his work. He became withdrawn and introspective, and his art grew progressively darker and more pessimistic. He experienced strange noises in his head and suffered from a nervous breakdown, admitting that his subsequent works were created to reflect his own self-doubt, anxiety, and fear of losing his mind. He stated that these works served "to occupy my imagination, tormented as it is by contemplation of my sufferings," and that they were pictures that "normally find no place in commissioned works."

During his convalescence between 1793 and 1794, Goya completed a set of eleven small pictures painted on tin, marking a significant change in the tone and subject matter of his art. These works delved into the dark and dramatic realms of fantasy and nightmare. Yard with Lunatics (1794), for instance, is a chilling vision of loneliness, fear, and social alienation, condemning the brutality towards prisoners and the mentally ill. This period saw his earlier pursuit of ideal beauty give way to an exploration of the relationship between naturalism and fantasy, a theme that would preoccupy him for the rest of his career.

In 1799, Goya published his influential series of aquatinted etchings known as the Caprichos (CaprichosSpanish, "Whims"). This collection of 80 prints, completed alongside more official commissions, depicted what Goya described as "the innumerable foibles and follies to be found in any civilized society, and from the common prejudices and deceitful practices which custom, ignorance, or self-interest have made usual." The series, which is considered a precursor to modern cartoons, uses dark humor and grotesque imagery to critique the superstitions, ignorance, and corruption prevalent in Spanish society and the Catholic Church. The famous subtitle, "The sleep of reason produces monsters," encapsulates the series' core message, though Goya's sharp satirical wit is also evident in prints like Capricho number 52, What a Tailor Can Do!.

In the late 1790s, commissioned by Manuel Godoy, Goya completed his groundbreaking La maja desnuda (The Nude Maja), followed by La maja vestida (The Clothed Maja) between 1800 and 1805. La maja desnuda has been described as "the first totally profane life-size female nude in Western art" without any pretense to allegorical or mythological meaning. The identity of the model for the Majas remains uncertain, with popular theories suggesting the Duchess of Alba or Pepita Tudó, Godoy's mistress, though it is equally likely that the paintings represent an idealized composite figure. These daring works were never publicly exhibited during Goya's lifetime and were owned by Godoy. In 1808, they were seized by Ferdinand VII after Godoy's fall from power, and in 1813, the Spanish Inquisition confiscated them as 'obscene,' though they were returned to the Academy of Fine Arts of San Fernando in 1836. Goya narrowly escaped the Inquisition's judgment.

In 1798, Goya painted luminous and airy scenes for the pendentives and cupola of the Real Ermita (Chapel) of San Antonio de la Florida in Madrid. His depiction of a miracle of Saint Anthony of Padua is notable for its departure from traditional religious iconography, treating the miracle as a theatrical event performed by ordinary people rather than featuring customary angels.

5.2. Peninsular War (1808-1814)

The French army's invasion of Spain in 1808 initiated the brutal Peninsular War (1808-1814). During this period, Napoleon Bonaparte installed his brother, Joseph I, as the King of Spain. Goya remained in Madrid throughout the war, a period that deeply affected him. While he maintained public neutrality, painting works for French patrons and sympathizers, his profound response to the conflict can be inferred from his later works. After the restoration of the Spanish King Ferdinand VII in 1814, Goya denied any involvement with the French regime, though his relations with the restored monarch remained strained. He completed portraits of the king for various ministries but notably not for the king himself.

By the time of his wife Josefa's death in 1812, Goya was already working on two of his most iconic historical paintings: The Second of May 1808 and The Third of May 1808, both completed in 1814. These works vividly depict the Dos de Mayo Uprising and the subsequent executions of Spanish rebels by French firing squads, capturing the horror and heroism of the events.

In parallel, Goya began preparing the series of etchings later known as The Disasters of War (Los desastres de la guerraSpanish), which he worked on from 1810 to 1820. Although Goya did not explicitly state his intentions for this series, art historians widely interpret it as a powerful visual protest against the violence of the 1808 uprising, the subsequent Peninsular War, and the suppression of liberalism that followed the restoration of the Bourbon monarchy in 1814. The scenes are singularly disturbing and often macabre, depicting battlefield horrors, atrocities, starvation, degradation, and humiliation. They represent an outraged conscience in the face of death and destruction, described as a "prodigious flowering of rage."

The series is divided into three main parts:

- The first 47 plates focus on incidents from the war itself, showing the brutal consequences of the conflict on individual soldiers and civilians.

- The middle series (plates 48 to 64) records the devastating effects of the famine that struck Madrid in 1811-12, before the city was liberated from the French.

- The final 17 plates reflect the bitter disappointment of liberals when the restored Bourbon monarchy, influenced by the Catholic hierarchy, rejected the Spanish Constitution of 1812 and opposed both state and religious reform.

The Disasters of War was not published until 1863, 35 years after Goya's death, likely because it was considered too politically sensitive to distribute a sequence of artworks that criticized both the French and the restored Bourbons.

Other works from his mid-period include the Caprichos and Los Disparates etching series, and a wide variety of paintings concerned with insanity, mental asylums, witches, fantastical creatures, and religious and political corruption. These works suggest Goya's fears for both his country's fate and his own mental and physical health.

From 1814 to 1819, Goya's output primarily consisted of commissioned portraits, but also included the altarpiece of Santa Justa and Santa Rufina for the Cathedral of Seville, and the print series of La Tauromaquia, depicting scenes from bullfighting. The authorship of the famous painting The Colossus (after 1808), which depicts a giant figure looming over fleeing crowds, has been disputed. While traditionally attributed to Goya, the Museo del Prado concluded in 2009 that it was likely the work of one of his followers, possibly Asensio Juliá, citing stylistic inconsistencies and the discovery of an "AJ" signature. However, this attribution remains a subject of debate among art historians.

5.3. Quinta del Sordo and Black Paintings (1819-1822)

Records of Goya's later life are relatively scant, as he increasingly worked in private and suppressed some of his politically sensitive works. Tormented by a dread of old age and the fear of madness, Goya, despite his earlier success as a royally placed artist, withdrew from public life during his final years. From the late 1810s, he lived in near-solitude outside Madrid in a farmhouse he converted into a studio. This house became known as "La Quinta del Sordo" (Quinta del SordoSpanish, "The House of the Deaf Man"), coincidentally named after a nearby farmhouse that also belonged to a deaf man.

Art historians believe that Goya felt deeply alienated from the social and political trends that followed the 1814 restoration of the Bourbon monarchy. He viewed these developments as reactionary means of social control and, in his unpublished art, seems to have railed against what he perceived as a tactical retreat into Medievalism. Like many liberals of his time, Goya had hoped for significant political and religious reform, but became profoundly disillusioned when the restored Bourbon monarchy and the Catholic hierarchy rejected the liberal Spanish Constitution of 1812.

At the age of 75, in a state of mental and physical despair, Goya embarked on the creation of his 14 (or possibly 15) Black Paintings. These powerful and disturbing works were executed directly in oil onto the plaster walls of his house between 1819 and 1823. Goya did not intend for these paintings to be exhibited, nor did he write or speak of them, unlike his earlier series like the Caprichos or The Disasters of War. The themes explored in the Black Paintings are deeply pessimistic, delving into madness, despair, and the darker, irrational aspects of human nature. Notable works include Saturn Devouring His Son and Witches' Sabbath (also known as Aquelarre), which depicts a grotesque gathering of figures presided over by a demonic goat-like creature.

Around 1874, about 50 years after Goya's death, the Black Paintings were removed from the walls of the Quinta del Sordo and transferred to canvas supports by their owner, Baron Frédéric Émile d'Erlanger. Many of the works were significantly altered during this restoration process, and in the words of art critic Arthur Lubow, what remains are "at best a crude facsimile of what Goya painted." The effects of time on the murals, coupled with the inevitable damage caused by the delicate operation of mounting the crumbling plaster on canvas, resulted in extensive damage and loss of paint. Today, the Black Paintings are on permanent display at the Museo del Prado in Madrid. The Otsuka Museum of Art in Japan has a reproduction of the "House of the Deaf Man" that replicates the original arrangement of the Black Paintings.

6. Personal Life

Francisco Goya's personal life, though less extensively documented than his artistic career, provides context for his emotional and thematic shifts. He married Josefa Bayeu on July 25, 1773. While they had seven children, only one, a son named Javier, survived into adulthood. Josefa passed away in 1812, a period during which Goya was deeply affected by the Peninsular War and began working on his powerful "Disasters of War" series.

After Josefa's death, Goya's household was managed by Leocadia Weiss (née Zorrilla, 1790-1856), his maid and a distant relative, who was 35 years his junior. Leocadia lived with and cared for Goya at his Quinta del Sordo villa until 1824, accompanied by her daughter, Rosario Weiss. There has been much speculation about the nature of Goya's relationship with Leocadia. She was married to a jeweler, Isidore Weiss, but separated from him in 1811 after he accused her of "illicit conduct." Leocadia had two children before this separation and gave birth to Rosario in 1814 when she was 26. Isidore was not Rosario's father, leading to frequent speculation, though with little firm evidence, that Rosario was Goya's child. While some suggest a romantic link between Goya and Leocadia, it is more likely that their affection was sentimental, given Goya's advanced age and declining health. Leocadia's features were reportedly similar to Goya's first wife, Josefa Bayeu, to the extent that one of Goya's portraits bears the cautious title of Josefa Bayeu (or Leocadia Weiss).

Goya did not leave anything to Leocadia in his will, a common practice for mistresses at the time, but it is also plausible that he avoided revising his will due to his reluctance to confront his own mortality. Leocadia, largely destitute after Goya's death, complained to his friends about her exclusion from the will, but many of them were also elderly or had passed away and did not respond. She later gave away her copy of the Caprichos for free.

7. Exile in Bordeaux and Death

In 1824, at the age of 78, Goya decided to leave Spain and go into exile in the French city of Bordeaux. This decision was largely influenced by the political unrest and the suppression of liberals in Spain following the restoration of the Bourbon monarchy. He sought refuge in Bordeaux, which had become a center for Spanish exiles. He was accompanied by his companion and maid, Leocadia Weiss, and her daughter Rosario.

During his final years in Bordeaux, Goya continued to paint and create. He briefly visited Paris between June and September 1824. In May and June 1826, he returned to Madrid temporarily to formally resign his position as court painter, ensuring his pension. He then returned to Bordeaux permanently. In this period, he completed his La Tauromaquia series, depicting scenes from bullfighting, and produced a number of other oil paintings, including The Milkmaid of Bordeaux (1825-27), which is believed to be a portrait of Leocadia Weiss. It is said that he rediscovered a sense of peace in his final days.

Goya's long and eventful life came to an end on April 16, 1828, in Bordeaux, at the age of 82. His death followed a stroke that left him paralyzed on his right side, and he had also suffered from reduced vision and a lack of painting materials in his last moments.

His body was initially buried in Bordeaux. Years later, his remains were re-interred in the Real Ermita de San Antonio de la Florida in Madrid, a chapel whose ceiling frescoes, depicting the Miracle of Saint Anthony, were painted by Goya himself. A curious and widely recounted detail of his re-interment is that Goya's skull was found to be missing from his grave in Bordeaux. The Spanish consul immediately reported this to his superiors in Madrid, who famously wired back, "Send Goya, with or without head." The circumstances surrounding the missing skull, including the perpetrators and their motives, remain unknown.

8. Artistic Characteristics and Themes

Goya's art is characterized by its remarkable versatility, technical innovation, and profound engagement with the human condition and societal issues. His career spanned a period of immense political and social upheaval in Spain, and his works serve as a powerful visual chronicle of these changes, moving from the lightheartedness of Rococo to the dark intensity of Romanticism.

8.1. Techniques and Mediums

Goya demonstrated mastery and innovation across a wide range of artistic techniques and mediums. He excelled in oil painting, producing grand portraits, historical scenes, and intimate cabinet paintings. His early works often featured bright, vibrant colors and delicate tonalities, reflecting the Rococo style. However, after his illness and subsequent deafness in 1793, his palette became noticeably darker, and his brushwork more expressive and daring, employing impasto and glazing techniques to achieve dramatic effects.

He was also a prolific and groundbreaking printmaker, particularly renowned for his use of etching and aquatint. These mediums allowed him to explore complex themes and express his political and social critiques with an immediacy and depth often absent in his commissioned paintings. His print series, such as the Caprichos, The Disasters of War, La Tauromaquia, and Los Disparates, are considered among the most important graphic works in art history, showcasing his innovative approach to line, tone, and composition.

Goya's skill extended to fresco painting, as evidenced by his work in the Basilica of Our Lady of the Pillar in Zaragoza and, most notably, the luminous and theatrical frescoes in the Royal Chapel of San Antonio de la Florida in Madrid. His later Black Paintings were unique in their execution, painted directly in oil onto the plaster walls of his home, the Quinta del Sordo, demonstrating his willingness to experiment with unconventional methods and surfaces.

8.2. Social Criticism and Psychological Exploration

Goya's art is deeply imbued with critical commentary on Spanish society, religion, and politics, making him a powerful voice for social justice and human rights. He meticulously documented the realities of his time, often exposing the hypocrisy, corruption, and irrationality he observed.

His early works, particularly the tapestry cartoons, often depicted scenes of everyday life, popular customs, and courtly activities, reflecting the *joie de vivre* and optimism of the Rococo era and the Enlightenment. However, even in these works, there was a subtle undercurrent of observation of human types and societal fads.

Following his severe illness and deafness in 1793, Goya's thematic concerns shifted dramatically towards darker and more pessimistic subjects. This period marked a profound psychological exploration in his art.

- Critique of Superstition and Ignorance: The Caprichos series is a prime example of his sharp satirical wit and his condemnation of widespread superstition, ignorance, and the abuses of power, particularly within the Church and aristocracy. Works like The Sleep of Reason Produces Monsters symbolize the dangers of unchecked irrationality.

- War and Inhumanity: The Peninsular War had a profound impact on Goya, leading him to create some of the most searing anti-war images in art history. The Second of May 1808 and The Third of May 1808 are powerful depictions of resistance and execution, while The Disasters of War etchings offer an unflinching, macabre, and outraged portrayal of the atrocities, starvation, and degradation inflicted by conflict. These works highlight the universal horrors of war and the suffering of both soldiers and civilians.

- Madness and the Grotesque: Goya frequently explored themes of madness, mental illness, and the grotesque. Paintings like Yard with Lunatics and his later Black Paintings delve into the psychological depths of despair, isolation, and the irrational aspects of the human psyche. He depicted mental asylums, witches, fantastical creatures, and scenes of religious fanaticism and political corruption, all of which suggested his fears for his country and his own mental and physical well-being.

- Disillusionment and Despair: His later works, culminating in the Black Paintings, reflect his increasing disillusionment with the political and social developments in Spain, particularly the reactionary turn after the Bourbon restoration. These intensely personal murals, painted in near-isolation, are a raw expression of his despair and his critical view of the darker aspects of human nature, making them a powerful testament to his artistic and psychological journey.

Goya's ability to express his personal demons as horrific and fantastic imagery, while simultaneously addressing universal themes, allows his audience to find their own catharsis in his works, solidifying his legacy as an artist who fearlessly confronted the complexities of his world.

9. Influence and Legacy

Francisco Goya's impact on art history is immense, earning him the unique distinction of being considered both the last of the Old Masters and the first of the moderns. His groundbreaking approach to subject matter, his bold techniques, and his profound psychological insights paved the way for subsequent art movements and continue to resonate with artists and audiences today.

9.1. Influence on Later Artists and Culture

Goya's influence extended far beyond the visual arts, permeating literature, music, and film.

- Visual Arts:

- 19th and 20th Century Masters: Spanish painters like Pablo Picasso and Salvador Dalí drew significant inspiration from Goya's works, particularly his Los Caprichos and Black Paintings. Picasso, in particular, studied Goya's etchings extensively and acknowledged his debt to the master's innovative graphic techniques and his unflinching portrayal of human suffering.

- Postmodern Artists: In the 21st century, American postmodern painters such as Michael Zansky and Bradley Rubenstein continue to find inspiration in Goya's *The Sleep of Reason Produces Monsters* and his *Black Paintings*. Zansky's "Giants and Dwarf Series" (1990-2002), for instance, directly incorporates imagery and themes from Goya's oeuvre into large-scale paintings and wood carvings.

- Music:

- The Spanish composer Enrique Granados was deeply inspired by Goya's paintings, leading him to compose the acclaimed piano suite Goyescas in 1911. He later adapted this suite into an opera of the same name.

- Literature:

- Spanish author Fernando Arrabal's novel *The Burial of the Sardine* was directly inspired by Goya's painting of the same name.

- Russian poet Andrei Voznesensky's powerful poem "I Am Goya" was a direct response to Goya's anti-war paintings, particularly *The Disasters of War*, reflecting the universal impact of Goya's depictions of conflict.

- Video Games: The video game *Impasto* was based on the works of Goya, demonstrating his enduring cultural relevance across different media.

- Exhibitions: Goya's work continues to be a subject of major exhibitions worldwide, such as the extensive exhibition of his etchings held at the Norton Simon Museum in Southern California in 2024.

- Films and Television: Goya's life and art have been the subject of numerous films and television productions, including:

- The Naked Maja* (1958), directed by Henry Koster, starring Anthony Franciosa as Goya and Ava Gardner as the Duchess of Alba.

- Goya or the Hard Way to Enlightenment* (German: Goya - oder der arge Weg der Erkenntnis) (1971), an East German drama film directed by Konrad Wolf, based on a novel by Lion Feuchtwanger.

- Goya in Bordeaux* (1999), a Spanish historical drama film written and directed by Carlos Saura.

- Volavérunt* (1999), directed by Bigas Luna, based on a novel by Antonio Larreta.

- Goya: Crazy Like a Genius* (2002), a documentary by Ian MacMillan, presented by Robert Hughes.

- Goya's Ghosts* (2006), directed by Miloš Forman.

- An episode of the Spanish series *The Ministry of Time*, titled "Tiempo de ilustrados (Time of the Enlightened)" (2017), features Goya (played by Pedro Casablanc) having to repaint *La maja desnuda*.

- El asesino de los caprichos* (2019), a Spanish crime mystery film.

- The Duke* (2020), a British film based on the real-life theft of Goya's *Portrait of the Duke of Wellington*.

10. Major Collections

The vast majority of Francisco Goya's most significant works are housed in major museums and galleries, primarily in Spain, reflecting his status as a national treasure.

The Museo del Prado in Madrid holds the most extensive and important collection of Goya's paintings, including many of his iconic masterpieces such as:

- Charles IV of Spain and His Family

- La maja desnuda and La maja vestida

- The Second of May 1808 and The Third of May 1808

- The complete series of the Black Paintings, transferred from the walls of his home, the Quinta del Sordo, including Saturn Devouring His Son and Witches' Sabbath.

Other notable collections and sites related to Goya in Spain include:

- The Real Ermita de San Antonio de la Florida in Madrid, where Goya's remains are interred and which features his magnificent frescoes on the cupola.

- The Casa natal de Goya (Goya's birthplace) in Fuendetodos, Aragon.

- The Museo del Grabado de Goya (Goya Engraving Museum) in Fuendetodos, dedicated to his printmaking.

- The Museo Goya in Zaragoza, which houses a collection of his works.

Internationally, Goya's works are also found in various prestigious institutions:

- The Goya Museum in Castres, France, holds a significant collection of his paintings.

- In Japan, the Tokyo Fuji Art Museum possesses Prince Don Sebastian Gabriel de Borbón y Braganza, and the Mie Prefectural Art Museum houses Portrait of Alberto Foraster.

- Numerous Japanese museums also hold significant collections of Goya's prints, including the National Museum of Western Art, the Machida City Museum of Graphic Arts, the Kanagawa Prefectural Museum of Modern Art, the Himeji City Museum of Art, and the Nagasaki Prefectural Art Museum.

- The Otsuka Museum of Art in Japan features a unique reproduction of Goya's "House of the Deaf Man," displaying the Black Paintings in their original wall arrangement.

- Major art museums worldwide, such as the National Gallery of Art in Washington, D.C., and the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York, also feature Goya's works in their collections.