1. Overview

Francis I (September 12, 1494 - March 31, 1547) served as the King of France from 1515 until his death. He ascended to the throne, succeeding his cousin once removed and father-in-law, Louis XII of France, who died without a legitimate male heir. Francis I is widely regarded as France's first monarch of the French Renaissance, fostering significant cultural advancements during his reign. His rule was marked by a flourishing of the arts, literature, and architecture, promoting humanism and the spread of Renaissance ideals across France.

His reign was also defined by complex international relations and military conflicts, most notably the protracted Italian Wars against his formidable rival, Emperor Charles V. Despite military setbacks, including his capture at the Battle of Pavia, Francis I pursued an assertive foreign policy, forging controversial alliances, such as with the Ottoman Empire, to counter Habsburg hegemony. Domestically, he initiated significant administrative reforms, including the landmark Ordinance of Villers-Cotterêts which established French as the official administrative language. While initially tolerant of new religious movements, his later policies saw a shift towards increased persecution of Protestants, reflecting the period's social and human rights challenges. Francis I's legacy is complex, encompassing both his profound cultural contributions and the strategic and sometimes controversial nature of his political decisions.

2. Early Life and Accession

Born at the Château de Cognac, Francis I's early life saw an unexpected path to the throne due to the application of Salic Law, shaping him through an education that embraced the emerging ideas of the Italian Renaissance.

2.1. Birth and Family Background

Francis was born on September 12, 1494, at the Château de Cognac in the town of Cognac, located in the historical province of Saintonge, a part of the Duchy of Aquitaine. He was the only son of Charles of Orléans, Count of Angoulême, and Louise of Savoy, and a great-great-grandson of King Charles V of France. His family belonged to the House of Valois, specifically the Orléans-Angoulême branch.

2.2. Childhood and Education

Francis's family was not initially expected to inherit the French throne, as his third cousin, King Charles VIII of France, was still young at the time of his birth, as was his father's cousin, the Duke of Orléans (who later became King Louis XII). However, Charles VIII died childless in 1498, and Louis XII, also lacking a male heir, became king. The application of the Salic Law, which prevented women from inheriting the throne, positioned the four-year-old Francis as the heir presumptive in 1498. He had already inherited the title of Count of Angoulême two years prior upon his father's death and was subsequently vested with the title of Duke of Valois.

During his education, Francis was exposed to the emerging ideas of the Italian Renaissance. Some of his tutors, including François de Moulins de Rochefort, his Latin instructor, and Christophe de Longueil, a Brabantian humanist, introduced him to new ways of thinking. His academic education covered subjects such as arithmetic, geography, grammar, history, reading, spelling, and writing, and he became proficient in Hebrew, Italian, Latin, and Spanish. Francis also learned chivalry, dancing, and music, and he enjoyed archery, falconry, horseback riding, hunting, jousting, real tennis, and wrestling. He delved into philosophy and theology and developed a deep fascination with art, literature, poetry, and science. His mother, Louise of Savoy, who greatly admired Italian Renaissance art, instilled this passion in her son. Although Francis did not receive a formal humanist education in the modern sense, he was more influenced by humanism than any previous French king.

2.3. Path to the Throne

In 1505, King Louis XII fell ill and ordered the immediate marriage of his daughter Claude of France and Francis. Their engagement was formally agreed upon through an assembly of nobles. Claude was the heir presumptive to the Duchy of Brittany through her mother, Anne of Brittany. Following Anne's death, the marriage took place on May 18, 1514. On January 1, 1515, Louis XII died without a male heir, and Francis inherited the throne. He was crowned King of France in the Cathedral of Reims on January 25, 1515, with Claude as his queen consort.

3. Reign and Major Policies

Francis I's reign was a pivotal period in French history, characterized by significant advancements in culture and the arts, a complex series of military engagements and diplomatic maneuvers, and crucial domestic reforms that shaped the future of the French state.

3.1. Cultural Patronage

Francis I played a pivotal role in fostering the French Renaissance and was an enthusiastic patron of artists and intellectuals, significantly enriching France's cultural landscape. When he ascended the throne in 1515, French royal palaces possessed few notable paintings and no sculptures, neither ancient nor modern.

3.1.1. Promotion of French Renaissance

Francis actively sought to attract leading artists and intellectuals from Italy to France, thereby accelerating the spread of Renaissance ideals and styles. He persuaded Leonardo da Vinci to make France his home during his final years, offering him the Château du Clos Lucé near the Château d'Amboise. Though da Vinci produced little new work in France, he brought many of his most celebrated pieces, including the `La JocondeFrench` (the Mona Lisa), which Francis had acquired. These masterpieces remained in France after da Vinci's death, significantly contributing to the royal collection. Other prominent artists who received Francis's patronage included Andrea del Sarto, the goldsmith Benvenuto Cellini, and painters such as Rosso Fiorentino, Giulio Romano, and Primaticcio, all of whom were instrumental in decorating Francis's various palaces. He also invited the architect Sebastiano Serlio, who enjoyed a fruitful career in France. Francis additionally commissioned agents in Italy to procure notable works of art and have them shipped to France, sometimes succeeding in challenging feats like attempting to transport Leonardo's The Last Supper.

3.1.2. Architectural and Artistic Projects

Francis invested vast sums of money into new construction projects and renovations, leaving a lasting architectural legacy. He continued the work of his predecessors on the Château d'Amboise and initiated renovations on the Château de Blois. Early in his reign, he began the construction of the magnificent Château de Chambord, which clearly displays the distinct styles of the Italian Renaissance architecture and may have even been designed by Leonardo da Vinci himself.

He rebuilt the Louvre Palace, transforming it from a medieval fortress into a building embodying Renaissance splendor. Francis also financed the construction of a new City Hall (the Hôtel de Ville) for Paris, ensuring royal control over its design. His other significant projects included the construction of the Château de Madrid in the Bois de Boulogne and the rebuilding of the Château de Saint-Germain-en-Laye. The largest of Francis's building endeavors was the reconstruction and expansion of the Château de Fontainebleau, which quickly became his favorite residence, as well as the residence of his official mistress, Anne, Duchess of Étampes. This palace was lavishly decorated both inside and out, featuring unique elements like a fountain that mixed wine with water for outdoor festivities. The impressive collection of artworks amassed by the French king, still visible today at the Louvre Museum, was largely acquired during Francis's reign.

3.1.3. Development of Royal Library and Letters

Francis I was also renowned as a man of letters and dedicated himself to improving the royal library. He appointed the French humanist Guillaume Budé as chief librarian and actively expanded the collection. Similar to his agents for art acquisition, Francis employed agents in Italy to search for rare books and manuscripts. The size of the royal library significantly increased during his reign. Importantly, evidence suggests he actually read the books he acquired, a rare practice among monarchs of the era. He set a crucial precedent by opening his library to scholars from around the world, thereby facilitating the diffusion of knowledge. In 1537, Francis signed the `Ordonnance de MontpellierFrench`, which mandated that his library receive a copy of every book sold in France. His elder sister, Marguerite, Queen of Navarre, was an accomplished writer, producing the classic collection of short stories known as the Heptaméron. Francis corresponded with the abbess and philosopher Claude de Bectoz, whose letters he so cherished that he would carry them and show them to the ladies of his court. He visited her in Tarascon along with his sister.

3.2. Military and Diplomatic Activities

Francis I's reign was largely shaped by a series of military campaigns and intricate diplomatic efforts, primarily aimed at countering the growing power of the Habsburg dynasty.

3.2.1. Italian Wars and Major Conflicts

Francis continued the Italian Wars (1494-1559) that he inherited from his predecessors. These conflicts were a constant feature of his reign, which he often led personally as `le Roi-ChevalierFrench` ('the Knight-King'). The wars began when Milan sought French protection against the aggressive actions of the Kingdom of Naples. His initial military success came early in his reign. In September 1515, Francis decisively routed the combined forces of the Papal States and the Old Swiss Confederacy at the Battle of Marignano, allowing him to capture the Italian city-state of Milan.

However, this victory was temporary. In November 1521, during the Four Years' War, he was forced to abandon Milan due to advancing Imperial forces and an internal revolt within the duchy.

His most significant military setback occurred at the Battle of Pavia on February 24, 1525, also during the Four Years' War. Despite leading his troops from the front, Francis was captured after his horse was injured by Cesare Hercolani. He was subsequently taken prisoner by Spanish officers including Diego Dávila, Alonso Pita da Veiga, and Juan de Urbieta. He was held in Madrid, famously writing to his mother, "Of all things, nothing remains to me but honour and life, which is safe," a line that became "All is lost save honour."

To secure his release, Francis was compelled to sign the Treaty of Madrid (1526) on January 14, making major concessions to Charles V. He was forced to surrender all claims to Naples and Milan in Italy, recognize the independence of the Duchy of Burgundy, which had been part of France since 1477, and was betrothed to Charles's sister, Eleanor of Austria. Francis was released on March 17, 1526, in exchange for his two sons, Francis and Henry, as hostages. However, once free, he promptly revoked the forced concessions, arguing that the agreement was made under duress and was therefore void. An ultimatum from Ottoman Sultan Suleiman the Magnificent to Charles V also played a role in Francis's release.

Francis persevered in his rivalry against Charles V and his ambition to control Italy. In the mid-1520s, Pope Clement VII, seeking to liberate Italy from foreign domination, particularly that of Charles V, allied with Venice to form the League of Cognac. Francis joined the League in May 1526, leading to the War of the League of Cognac (1526-1530). However, Francis's allies proved weak, and the war concluded with the Treaty of Cambrai (1529), known as "the Peace of the Ladies," negotiated by Francis's mother and Charles V's aunt. The two hostage princes were released, and Francis married Eleanor as part of the agreement.

On July 24, 1534, Francis, inspired by Spanish and Roman military formations, issued an edict to form seven infantry Legions of 6,000 troops each. Of the 42,000 troops, 12,000 were to be arquebusiers, demonstrating the increasing importance of gunpowder. This force constituted a national standing army where soldiers could be promoted based on merit, were paid wages by grade, and received exemptions from the taille and other taxes, posing a significant burden on the state budget, up to 20 sous.

After the failure of the League of Cognac, Francis entered a secret alliance with Philip I, Landgrave of Hesse on January 27, 1534, ostensibly to help the Duke of Württemberg regain his traditional seat from which Charles V had removed him. This led to a renewal of conflict in Italy in the Italian War of 1536-1538 after the death of Francesco II Sforza, ruler of Milan. This round of fighting, yielding little decisive result, ended with the Truce of Nice. The agreement eventually collapsed, leading to Francis's final attempt on Italy in the Italian War of 1542-1546. Francis I successfully held off the forces of Charles V and Henry VIII of England, with Charles V ultimately forced to sign the Treaty of Crépy due to his financial difficulties and conflicts with the Schmalkaldic League.

3.2.2. Rivalry with Holy Roman Emperor Charles V

A central and defining feature of Francis I's foreign policy was his intense personal and geopolitical rivalry with Emperor Charles V. Their struggle was a constant threat to Francis's kingdom, as Charles V personally ruled Spain, Austria, and the Habsburg Netherlands, effectively encircling France with Habsburg possessions. Francis had attempted to become Holy Roman Emperor himself in the Imperial election of 1519 but failed, largely due to Charles V's threats of violence against the electors. This rivalry profoundly impacted the balance of power in Western Christendom, contributing to the spread of the Protestant Reformation and enabling the expansion of the Ottoman Empire further into Europe, including the Siege of Vienna which saw most of the Kingdom of Hungary occupied.

3.2.3. Alliances and International Relations

Francis pursued various diplomatic initiatives to counterbalance Charles V's power. He sought an alliance with Henry VIII of England, culminating in the famous meeting at the Field of the Cloth of Gold on June 7, 1520. Despite a lavish fortnight of diplomacy, no agreement was reached. Both kings shared aspirations for power and chivalric glory, but their intense personal and dynastic rivalry, coupled with Francis's eagerness to retake Milan and Henry's determination to regain northern France, prevented a lasting alliance.

When the alliance with England proved unsuccessful, Francis undertook a highly controversial but strategic move: forming a Franco-Ottoman alliance with the Muslim sultan Suleiman the Magnificent. This alliance, unprecedented between a major Christian power and a non-Christian empire, caused considerable scandal in the Christian world, being labeled "the impious alliance" or "the sacrilegious union of the [French] Lily and the [Ottoman] Crescent."

However, it served the objective interests of both parties by providing a crucial counterweight to the Habsburgs. The alliance endured for many years, with the two powers colluding against Charles V. In 1543, they even combined for a joint naval assault during the siege of Nice. The pretext Francis used for this alliance was the protection of Christians in Ottoman lands.

Beyond this, Francis I also initiated formal diplomatic relations with Morocco. In 1533, he sent Colonel Pierre de Piton as ambassador to Morocco, and in a letter dated August 13, 1533, the Wattassid ruler of Fez, Ahmed ben Mohammed, welcomed French overtures and granted freedom of shipping and protection to French traders.

3.3. Overseas Exploration and Colonialism

Francis I's reign also saw the beginning of French involvement in overseas exploration, laying foundational groundwork for a future French colonial empire in the New World. He was deeply aggrieved by the papal bull Aeterni regis (1481), which confirmed Portuguese rule over Africa and the Indies, and the subsequent Treaty of Tordesillas (1494), which divided newly discovered lands between Portugal and the Crown of Castile. This prompted his famous declaration, "The sun shines for me as it does for others. I would very much like to see the clause of Adam's will by which I should be denied my share of the world."

To counterbalance the Habsburg Empire's control over large parts of the New World through Spain, Francis endeavored to develop French contacts with the Americas and Asia. The port city now known as Le Havre was founded in 1517 during his early reign, a new port desperately needed to replace the ancient harbors of Honfleur and Harfleur, which had declined due to silting. Le Havre was initially named Franciscopolis after the king, though this name did not endure.

In 1524, Francis supported the citizens of Lyon in financing the expedition of Giovanni da Verrazzano to North America. Verrazzano explored the eastern coast, visiting the future site of New York City, which he named New Angoulême, and claiming Newfoundland for the French crown. His letter to Francis from July 8, 1524, is known as the Cèllere Codex. In 1531, Bertrand d'Ornesan attempted to establish a French trading post at Pernambuco, Brazil.

In 1534, Francis dispatched Jacques Cartier to explore the St. Lawrence River in Quebec, explicitly to search for "certain islands and lands where it is said there must be great quantities of gold and other riches." Cartier's expeditions in 1534, 1535, 1541, and 1544, despite significant losses due to harsh winters and diseases and a lack of immediate material gain, were crucial in mapping the region and laying the groundwork for French colonization of Canada. In 1541, Francis sent Jean-François Roberval to settle Canada and promote the spread of "the Holy Catholic faith." These voyages paved the way for the expansion of the first French colonial empire.

French trade with East Asia also began during Francis I's reign, with the assistance of shipowner Jean Ango. A French Norman trading ship from Rouen reportedly arrived in the Indian city of Diu in July 1527, as recorded by the Portuguese João de Barros. In 1529, Jean Parmentier, aboard the `SacreFrench` and the `PenséeFrench`, reached Sumatra. The expedition's return spurred the development of the Dieppe maps, influencing Dieppe cartographers such as Jean Rotz.

3.4. Domestic Reforms and Language Policy

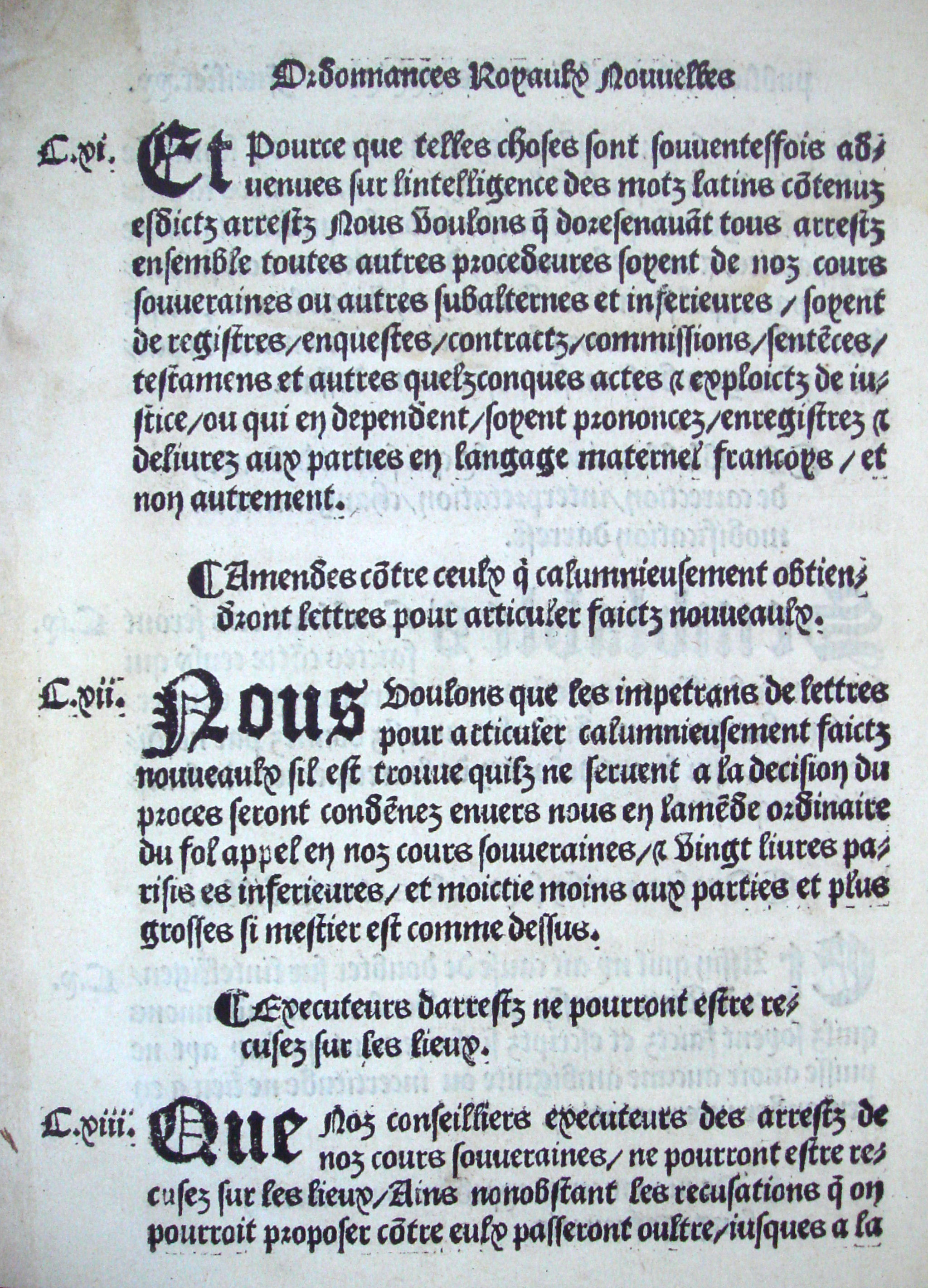

Francis I undertook significant internal reforms, particularly concerning the French language and state administration. In 1530, following the recommendation of the humanist Guillaume Budé, he declared French the national language of the kingdom. In the same year, he opened the `Collège RoyalFrench` (later known as the Collège de France), where students could study Greek, Hebrew, and Aramaic, and from 1539, Arabic under Guillaume Postel. This demonstrated a proactive effort to break the monopoly of Latin as the language of knowledge.

His most impactful reform was the Ordinance of Villers-Cotterêts, signed in August 1539 at his castle in Villers-Cotterêts. This edict, among other reforms, mandated French as the administrative language of the kingdom, replacing Latin. It also required priests to register births, marriages, and deaths, and to establish a registry office in every parish. This initiative established the first records of vital statistics with filiations available in Europe, marking a significant step in centralized civil administration.

3.5. Religious Policies and Conflicts

Francis I's reign coincided with the rise of the Protestant Reformation, which created profound and lasting divisions within Christianity in Western Europe. Initially, Francis adopted a relatively tolerant stance towards the new movement. This approach was partly influenced by his beloved sister, Marguerite de Navarre, who was genuinely attracted to Martin Luther's theology. Furthermore, Francis perceived political utility in the spread of Protestantism, as it encouraged many German princes to oppose his formidable rival, Charles V.

However, Francis's attitude towards Protestantism dramatically shifted for the worse following the "Affair of the Placards" on the night of October 17, 1534. During this incident, notices denouncing the Catholic mass appeared on the streets of Paris and other major cities, with one even being affixed to the door of the King's bedchamber. The author of these placards was the Protestant pastor Antoine Marcourt. This outrage galvanized fervent Catholics and led Francis to view the movement as a direct plot against his authority. Consequently, he began to persecute its followers, leading to the imprisonment and execution of Protestants. In some areas, entire villages were destroyed. After 1540 in Paris, Francis ordered the torture and burning of heretics such as Étienne Dolet. Printing was censored, and leading Protestant reformers, including John Calvin, were forced into exile. These persecutions resulted in thousands of deaths and tens of thousands becoming homeless.

The persecutions against Protestants were formally codified in the Edict of Fontainebleau (1540), issued by Francis. Major acts of violence continued, notably when Francis ordered the extirpation of the Waldensians, one of the historical pre-Lutheran groups, at the Massacre of Mérindol in 1545. These actions reflect the severe social and human rights impacts of his evolving religious policies.

4. Personal Life

Francis I's personal life was characterized by his royal marriages and influential relationships with his mistresses, which often played a role in the court's political dynamics.

4.1. Marriages and Children

On May 18, 1514, Francis married his second cousin, Claude of France, the daughter of King Louis XII of France and Anne of Brittany. Together, they had seven children:

- Louise (August 19, 1515 - September 21, 1518): Died young; engaged to Charles I of Spain almost from birth.

- Charlotte (October 23, 1516 - September 8, 1524): Died young; engaged to Charles I of Spain from 1518.

- Francis (February 28, 1518 - August 10, 1536): Succeeded his mother Claude as Duke of Brittany and became Dauphin (heir apparent) of France. He died at age 18, unmarried and childless.

- Henry II (March 31, 1519 - July 10, 1559): Succeeded his father Francis I as King of France and his brother Francis as Duke of Brittany. He married Catherine de' Medici and had issue.

- Madeleine (August 10, 1520 - July 2, 1537): Married James V of Scotland and had no issue.

- Charles (January 22, 1522 - September 9, 1545): Died unmarried and childless, holding the title of Duke of Orléans.

- Margaret (June 5, 1523 - September 14, 1574): Married Emmanuel Philibert, Duke of Savoy and had issue.

After Claude's death, Francis I married his second wife, Eleanor of Austria, on July 4, 1530. Eleanor was the widowed Queen of Portugal and the sister of Emperor Charles V. They had no children.

4.2. Mistresses and Other Relationships

During his reign, Francis I maintained two official mistresses at court. He was the first French king to officially bestow the title of "maîtresse-en-titre" on his favorite mistress. His first official mistress was Françoise de Foix, Countess of Châteaubriant, who had previously served as a lady-in-waiting to his first wife, Queen Claude. In 1526, Françoise was succeeded by the cultured, blonde-haired Anne de Pisseleu d'Heilly, Duchess of Étampes. With the death of Queen Claude two years prior, Anne wielded significantly more political power at court than her predecessor. It is also alleged that one of his earlier mistresses was Mary Boleyn, who was also a mistress of King Henry VIII of England and the sister of Henry's future wife, Anne Boleyn.

Francis also had an illegitimate child, Louis de Saint-Gelais (c. 1512/1513-1593), with Jacquette de Lanssac. Louis de Saint-Gelais later married Jeanne de La Roche-Andry and then Gabrielle de Rochechouart, with whom he had issue.

5. Death

Francis I died at the Château de Rambouillet on March 31, 1547, which was coincidentally his son and successor's 28th birthday. It is said that at the time of his death, "he died complaining about the weight of a crown that he had first perceived as a gift from God." He was interred alongside his first wife, Claude, Duchess of Brittany, in the Saint Denis Basilica, the traditional burial place for French monarchs. He was succeeded by his son, Henry II of France.

His tomb, along with those of his wife and mother, and other French kings and royal family members, was desecrated on October 20, 1793, during the Reign of Terror at the height of the French Revolution.

6. Legacy and Historical Assessment

Francis I's legacy is rich and complex, reflecting both the grandeur of the French Renaissance and the tumultuous political landscape of his era.

6.1. Image and Reputation

Francis I's image and reputation have varied considerably throughout history. In France, his 500th anniversary in 1994 received little attention, perhaps reflecting a lingering negative perception. Popular and scholarly historical memory often overlooks his extensive construction projects, his magnificent art collection, and his generous patronage of scholars and artists. Instead, he has sometimes been portrayed as a playboy who disgraced France by being defeated and taken prisoner at the Battle of Pavia. The historian Jules Michelet was instrumental in establishing this negative image.

Francis's personal emblem was the salamander, accompanied by his Latin motto `Nutrisco et extinguoLatin` ("I nourish [the good] and extinguish [the bad]"). His distinctive long nose earned him the nickname `François du Grand NezFrench` ('Francis of the Big Nose'). He was also colloquially known as `Grand ColasFrench` or `Bonhomme ColasFrench`. For his personal involvement in battles, he was widely known as `le Roi-ChevalierFrench` ('the Knight-King') or `le Roi-GuerrierFrench` ('the Warrior-King').

British historian Glenn Richardson offers a more positive assessment, highlighting Francis's effectiveness as a ruler:

"He was a king who ruled as well as reigned. He knew the importance of war and a high international profile in staking his claim to be a great warrior-king of France. In battle, he was brave, if impetuous, which led equally to triumph and disaster. Domestically, Francis exercised the spirit and letter of the royal prerogative to its fullest extent. He bargained hard over taxation and other issues with interest groups, often by appearing not to bargain at all. He enhanced royal power and concentrated decision-making in a tight personal executive but used a wide range of offices, gifts and his own personal charisma to build up an elective personal affinity among the ranks of the nobility upon whom his reign depended .... Under Francis, the court of France was at the height of its prestige and international influence during the 16th century. Although opinion has varied considerably over the centuries since his death, his cultural legacy to France, to its Renaissance, was immense and ought to secure his reputation as among the greatest of its kings."

6.2. Positive Evaluations and Achievements

Francis I's reign is most notably celebrated for the flourishing of the French Renaissance. His unparalleled patronage attracted leading Italian artists and intellectuals, including Leonardo da Vinci, whose masterpieces, such as the Mona Lisa, significantly enriched France's cultural heritage. He spearheaded ambitious architectural projects like the Château de Chambord and the renovation of the Louvre Palace, transforming medieval fortresses into Renaissance palaces that set new standards for royal residences. His efforts to expand the royal library and support humanists like Guillaume Budé fostered a vibrant intellectual environment, with the establishment of the `Collège RoyalFrench` promoting the study of classical and oriental languages. Furthermore, his decisive action through the Ordinance of Villers-Cotterêts formalized French as the administrative language, a crucial step in national linguistic and administrative unity, and established a groundbreaking system for civil registration.

In foreign policy, despite the setbacks, Francis I's strategic diplomatic maneuvers, particularly his controversial alliance with the Ottoman Empire, demonstrated a pragmatic approach to international relations. This alliance, though scandalous to many, was a bold move to counter Habsburg encirclement, securing French interests against a dominant European power. His initiation of overseas explorations, notably Jacques Cartier's voyages to North America, laid the foundational groundwork for France's future colonial empire.

6.3. Criticisms and Controversies

Despite his significant achievements, Francis I's reign faced various criticisms and controversies. His military endeavors, particularly the protracted Italian Wars, were exceedingly expensive and often ended in military setbacks, most notably his capture at the Battle of Pavia. These conflicts drained the royal treasury, leading to substantial expenditures that burdened the state. While he devised innovative methods of financing, such as long-term annuities secured by royal assets and taxation rights, these often came with high interest rates (notably an annual interest rate of no less than 10%) due to a lack of royal credit.

His evolving stance on the Protestant Reformation also drew significant criticism. Initially tolerant, his policies shifted dramatically after the "Affair of the Placards," leading to severe persecution of Protestants. This included imprisonments, executions, destruction of villages, censorship of printing, and forced exiles, such as that of John Calvin. The Massacre of Mérindol in 1545, where Waldensians were brutally suppressed, stands as a particularly dark episode, reflecting a harsh approach to religious dissent that led to significant human rights violations and social upheaval. These actions run counter to principles of social equity and religious freedom, marking a somber aspect of his legacy.

7. In Popular Culture

Francis I has been a recurring figure in various forms of popular culture, reflecting the dramatic and influential nature of his reign.

His amorous exploits and the intrigue of his court inspired Fanny Kemble's 1832 play, Francis the First. The same year, Victor Hugo published his play `Le Roi s'amuseFrench` ("The King's Amusement"), which featured the jester Triboulet. This play later served as the inspiration for Giuseppe Verdi's acclaimed 1851 opera, Rigoletto. Hugo's play, which depicted the corruption of the privileged class, was controversial and banned after its initial performance, not being staged again until 1882. Francis I is also referenced in Marcel Proust's novel In Search of Lost Time, where the narrator discusses a book about the rivalry between Francis I and Charles V.

In film, Francis I has been portrayed by numerous actors. An unknown actor, possibly Georges Méliès himself, first played him in Méliès' short film `François Ier et TribouletFrench` (1907). Subsequent portrayals include Claude Garry (1910), William Powell (1922), Aimé Simon-Girard (1937), Sacha Guitry (1937), Gérard Oury (1953), Jean Marais (1955), Pedro Armendáriz (1956), Claude Titre (1962), Bernard Pierre Donnadieu (1990), Timothy West (1998), Emmanuel Leconte (2007-2010), Alfonso Bassave (2015-2016), and Colm Meaney (2022). Various portraits of Francis I also exist, including a 1525-1530 work by Jean Clouet housed in the Louvre, and a 1532-1533 portrait by Joos van Cleve, which may have been commissioned for a meeting with Henry VIII or his second marriage, with copies distributed to other courts.

8. Ancestry

Francis I was born to Charles of Orléans, Count of Angoulême, and Louise of Savoy. His paternal grandfather was John, Count of Angoulême, and his paternal grandmother was Margaret of Rohan. On his maternal side, his grandfather was Philip II, Duke of Savoy, and his grandmother was Margaret of Bourbon.

Tracing his lineage further, his paternal great-grandparents were Louis I, Duke of Orléans, and Valentina Visconti, Duchess of Orléans. His paternal great-great-grandparents included Alan IX, Viscount of Rohan, and Margaret of Brittany. His maternal great-grandparents were Louis, Duke of Savoy, and Anne of Cyprus. Further back on his maternal side, his great-great-grandparents were Charles I, Duke of Bourbon, and Agnes of Burgundy, Duchess of Bourbon. This lineage connects him directly to prominent European noble houses, including the Valois and Savoy dynasties.