1. Overview

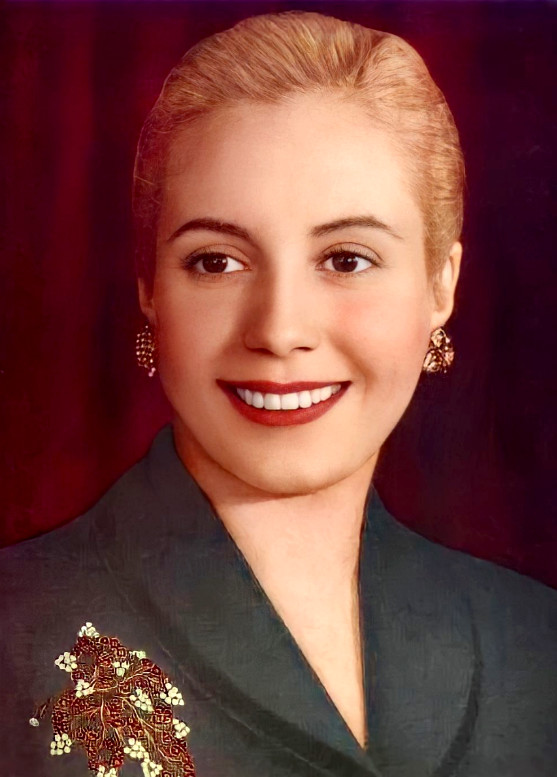

María Eva Duarte de Perón (born María Eva Ibarguren; May 7, 1919 - July 26, 1952), popularly known as **Eva Perón** or affectionately **Evita**, was a pivotal Argentine political figure, activist, actress, and philanthropist who served as First Lady of Argentina from June 1946 until her death in July 1952. As the second wife of Argentine President Juan Perón, she emerged from poverty to become a powerful advocate for the working class, women's rights, and social welfare, fundamentally reshaping Argentine society.

Born into destitution in rural Los Toldos, Argentina, Eva Duarte moved to Buenos Aires at 15 to pursue an acting career, eventually achieving success in radio, film, and theater. Her meeting with Juan Perón in 1944 marked the beginning of a powerful political partnership. As First Lady, she became a central figure in the Peronist movement, championed labor rights, and significantly influenced government policy despite holding no official political office. She established and directed the Eva Perón Foundation, a charitable organization that provided extensive social welfare, healthcare, and housing programs, widely impacting the poor and working class.

Eva Perón was instrumental in securing women's suffrage in Argentina and founded the Female Peronist Party, the nation's first large-scale women's political party, which significantly mobilized female voters. Her 1947 "Rainbow Tour" of Europe aimed to improve Argentina's international image. In 1951, she announced her candidacy for Vice President, garnering immense popular support, particularly from the working-class descamisados, but withdrew due to opposition from the military and her rapidly declining health. Diagnosed with advanced cervical cancer, she succumbed to the illness at the age of 33, receiving a state funeral and posthumously being declared "Spiritual Leader of the Nation of Argentina."

Eva Perón's legacy remains profoundly influential and complex. She is revered by many Argentines as a symbol of social justice and empowerment for the disadvantaged, her image often placed alongside religious icons. However, her political activities and the Peronist regime also drew criticism, including allegations of authoritarianism and financial impropriety. Her life and impact have been widely portrayed in international popular culture, most famously in the musical Evita, solidifying her status as a global icon.

2. Early Life and Background

Eva Perón's early life was marked by poverty and social stigma, experiences that profoundly influenced her worldview and fueled her ambition.

2.1. Childhood and Education

María Eva Duarte was born on May 7, 1919, in Los Toldos, a small rural village in Buenos Aires. Her birth certificate, possibly a forgery created for her marriage in 1945, recorded her name as María Eva Duarte with a birth year of 1922. However, her baptismal certificate lists her birth date as May 7, 1919, under the name Eva María Ibarguren. She was the youngest of five children born to Juana Ibarguren, an unmarried Basque cook, and Juan Duarte, a wealthy rancher of French Basque descent who already had a legal wife and family. At the time, it was not uncommon for affluent men in rural Argentina to have multiple families.

When Eva was one year old, Juan Duarte returned permanently to his legitimate family, abandoning Juana Ibarguren and her children to abject poverty. The family was forced to relocate to the poorest area of nearby Junín, where they lived in a single-room apartment. To support her children, Juana Ibarguren worked as a seamstress for neighbors. The family endured significant social stigma due to their father's abandonment and the children's illegitimate status under Argentine law, leading to their isolation. This painful part of her past may have motivated Eva to arrange for the destruction of her original birth certificate later in life.

The abandonment by their father left the family without his sole means of support, though he did leave a document declaring the children as his, enabling them to use the Duarte surname. Eva's older brother later provided financial assistance, allowing the family to move into a larger house in Junín, which they subsequently converted into a boarding house. During her childhood, Eva frequently participated in school plays and concerts, developing a strong interest in acting. Her passion for the stage was solidified in October 1933 when she played a small role in a school play titled Arriba Estudiantes (Students Arise), a patriotic melodrama. Despite her mother's desire for her to marry a local bachelor, Eva harbored dreams of becoming a famous actress.

A stark incident occurred during Juan Duarte's funeral in 1926. When Juana Ibarguren and her children attempted to attend, they were met with an unpleasant scene at the church gates. Though permitted to enter and pay their respects briefly, they were quickly escorted out on the orders of Duarte's legitimate widow, who did not wish her late husband's mistress and illegitimate children present. This event left a lasting bitter memory for Eva and her family.

2.2. Acting Career

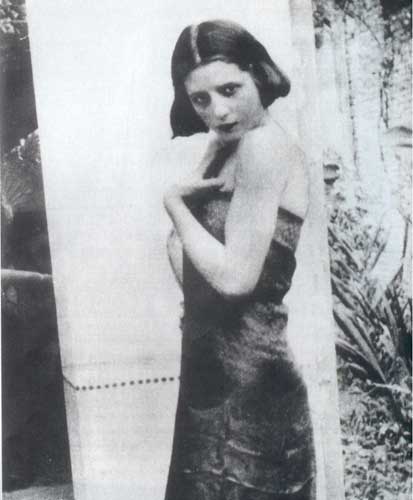

In 1934, at the age of 15, Eva Duarte, driven by her aspiration to become a film star, departed her impoverished village for the nation's capital, Buenos Aires. Accounts vary on how she traveled; while some suggest she traveled with tango singer Agustín Magaldi (a popular version in later cultural depictions), her sisters maintain that she was accompanied by their mother, who also arranged for Eva to live with family friends, the Bustamantes, and attended her radio station audition.

Buenos Aires in the 1930s, often called the "Paris of South America," presented a stark contrast between its bustling, sophisticated center and the widespread unemployment, poverty, and hunger that forced many new arrivals from rural areas into overcrowded tenements and shanties known as villas miserias. Upon her arrival, Eva faced considerable challenges, lacking formal education or influential connections.

She made her professional debut on March 28, 1935, in the play Mrs. Perez (La Señora de Pérez) at the Comedias Theater. In 1936, she toured nationally with a theater company, worked as a model, and appeared in several B-grade melodrama films. Her career gained stability in 1942 when she secured a daily role in the radio drama Muy Bien for Radio El Mundo, then the country's most important radio station, sponsored by a soap manufacturer. Later that year, she signed a five-year contract with Radio Belgrano, starring in the popular historical-drama program Great Women of History, where she portrayed historical figures such as Elizabeth I of England, Sarah Bernhardt, and Alexandra Feodorovna, the last Tsarina of Russia.

Eva Duarte eventually became a co-owner of the radio company. By 1943, she was earning 5.00 K ARS to 6.00 K ARS pesos per month, making her one of Argentina's highest-paid radio actresses. Though her film career during the Golden Age of Argentine Cinema was short-lived and without major successes, her radio work brought her significant financial stability. In 1942, she moved into an apartment in the upscale Recoleta neighborhood. The following year, she began her political career as one of the founders of the Argentine Radio Syndicate (ARA). Throughout this period, she dyed her naturally black hair blonde, a look she maintained for the rest of her life.

3. Relationship with Juan Perón

Eva Duarte's political journey began with her fateful meeting and subsequent marriage to Juan Perón, an alliance that would fundamentally alter the course of Argentine history.

On January 15, 1944, a devastating earthquake struck San Juan, Argentina, claiming the lives of approximately 10,000 people. In response, Juan Perón, then serving as Secretary of Labour, organized a national fundraising effort for the victims, which included an "artistic festival" inviting prominent radio and film actors.

It was at the subsequent gala, held at Luna Park Stadium in Buenos Aires on January 22, 1944, that Eva Duarte first met Colonel Juan Perón. Eva quickly became his girlfriend, later referring to that day as her "marvelous day." (Perón's first wife, Aurelia Tizón, had died of uterine cancer in 1938.)

Before meeting Perón, Eva Duarte had no prior interest or knowledge in politics. Juan Perón, who was 48 at the time (24 years older than Eva), later stated in his memoir that he intentionally chose Eva as his protégé, aiming to create a "second I" in her. Due to his relatively late entry into politics, he was open to her unconventional aid and allowed her intimate access to his inner circle.

In May 1944, an announcement mandated that broadcast performers organize into a single, officially recognized union. Eva Duarte was elected president of this union, likely influenced by Juan Perón's suggestion to form such an organization and the political expediency of electing his mistress. Following her election, Eva Duarte launched a daily radio program, Toward a Better Future, a soap opera dramatizing Juan Perón's achievements, often incorporating his speeches. She adopted an ordinary, relatable tone, aiming to convince listeners of her genuine belief in Perón's vision.

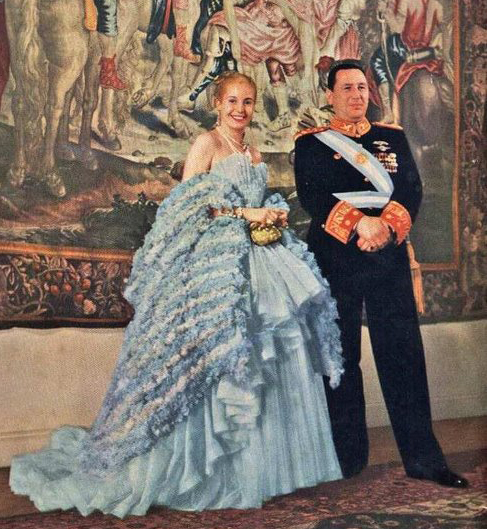

On October 18, 1945, the day after his release from prison, Juan Perón and Eva discreetly married in a civil ceremony in Junín. A church wedding followed on December 9, 1945, in La Plata. This union solidified their personal and political bond, setting the stage for their ascent to national power.

4. Rise to Power and Political Activities

Eva Perón's marriage to Juan Perón propelled her into the political arena, where she quickly became an influential force, initiating significant social and political changes.

In the early 1940s, a group of army officers known as the "Grupo de Oficiales Unidos" (United Officers' Group), or "The Colonels," exerted considerable influence within the Argentine government. President Pedro Pablo Ramírez grew wary of Juan Perón's increasing power, eventually signing his own resignation paper, drafted by Perón himself. Edelmiro Julián Farrell, a friend of Perón's, then became president, and Perón resumed his role as Labor Minister, solidifying his position as the most powerful figure in the government.

However, on October 9, 1945, Perón was arrested by political opponents who feared his strong base of support among unskilled unionized workers and allied trade unions would lead to a power grab. Six days later, on October 17, 1945, between 250,000 and 350,000 people gathered in front of the Casa Rosada, Argentina's government house, demanding Perón's release. At 11 p.m., Perón appeared on the balcony, addressing the crowd in a moment that biographer Robert D. Crassweller described as powerfully recalling Argentine historical traditions of a caudillo addressing his people. This event is now celebrated annually as Día de la Lealtad (Loyalty Day) by the Justicialist Party.

While Peronist rhetoric, especially after Perón's 1946 election, often portrayed Eva Perón as a central figure who single-handedly mobilized the masses on October 17, historians generally agree this depiction is a fictionalized account popularized by media like the Evita musical. At the time of Perón's imprisonment, Eva was primarily an actress with limited political influence among the labor unions and not widely popular even within Perón's inner circle. The massive rally that secured Perón's release was primarily organized by various unions, particularly the CGT, which formed Perón's core support base.

After his release, Juan Perón successfully campaigned for the presidency, winning with 54% of the vote in 1946. Eva played a crucial role in his campaign, using her weekly radio show to deliver speeches filled with populist rhetoric, urging the poor to support Perón's movement. Despite her own newfound wealth from her acting career, she highlighted her impoverished origins to demonstrate solidarity with the less fortunate. She became the first woman in Argentine history to appear publicly alongside her husband during a political campaign, visiting all corners of the country.

4.1. Eva Perón Foundation

Before Juan Perón's election, most charitable activities in Buenos Aires were managed by the Sociedad de Beneficencia de Buenos Aires (Society of Beneficence), an organization of 87 aristocratic ladies. Historically, the Sociedad cared for orphans and homeless women, supported by private contributions. By the 1940s, however, it relied on government funding. Traditionally, the First Lady of Argentina served as the charity's president. However, the Sociedad ladies disapproved of Eva Perón's humble background, lack of formal education, and former acting career, fearing she would set a poor example for the orphans and thus denied her the position.

In response, Eva Perón established her own charitable organization, the Eva Perón Foundation, on July 8, 1948. While some claimed this was retaliation leading to the cessation of government funding for the Sociedad, the funding previously supporting the Sociedad was indeed redirected to Eva's foundation. It began with an initial 10.00 K ARS pesos provided by Eva herself.

While critics like Mary Main alleged that the foundation lacked proper accounting records and served as a conduit for funneling government money into private Swiss bank accounts, biographers Nicholas Fraser and Marysa Navarro argue that Minister of Finance Ramón Cereijo maintained records, and that the foundation "began as the simplest response to the poverty [Evita] encountered each day in her office" and aimed to address "the appalling backwardness of social services... in Argentina." Robert D. Crassweller noted that the foundation was supported by cash and goods from Peronist unions, private businesses, and a levy on every worker's salary (initially three, later two days' wages per year). Additional funding came from taxes on lottery and movie tickets, and revenue from casinos and horse races. Crassweller also acknowledged that some businesses were pressured into making donations, facing negative consequences if they refused.

Within a few years, the foundation's assets in cash and goods exceeded 3.00 B ARS pesos, equivalent to over 200.00 M USD in the late 1940s. It employed 14,000 workers, including 6,000 construction workers and 26 priests. Annually, it purchased and distributed 400,000 pairs of shoes, 500,000 sewing machines, and 200,000 cooking pots. The foundation also provided scholarships and constructed homes, hospitals, and other charitable institutions. Every aspect was under Eva's direct supervision. The foundation even built entire communities, such as Ciudad Evita, which still exists today. Its extensive work and health services contributed to unprecedented equality in Argentine healthcare.

Towards the end of her life, Eva Perón was dedicating 20 to 22 hours daily to her foundation, often disregarding her husband's pleas to reduce her workload. Her direct engagement with the poor intensified her outrage at the existence of poverty. She reportedly said, "Sometimes I have wished my insults were slaps or lashes. I've wanted to hit people in the face to make them see, if only for a day, what I see each day I help the people." Crassweller described her as fanatical in her work, akin to being on a crusade against poverty and social ills, comparing her dedication to that of Ignatius of Loyola, transforming her into a "one-woman Jesuit Order." She would often set aside hours each day to personally meet with the poor, often embracing them and allowing them to kiss her. There were even accounts of her touching the wounds of the sick, including those with leprosy, and kissing individuals with syphilis, which, in the context of Argentina's predominantly Catholic culture, was perceived by some as elevating her to the characteristics of a saint.

4.2. Women's Suffrage and the Female Peronist Party

Eva Perón is widely recognized for her crucial role in securing voting rights for Argentine women. While her public addresses on radio and articles in her Democracia newspaper urged male Peronists to support women's suffrage, her direct power to enact such a law was limited. Her efforts focused on supporting a bill introduced by one of her proponents, Eduardo Colom, although that specific bill was eventually dropped.

A new women's suffrage bill was subsequently introduced. It received sanction from the Senate of Argentina on August 21, 1946, and, after over a year of waiting, was finally sanctioned by the House of Representatives on September 9, 1947. This legislation, Law 13,010, established political equality and universal suffrage for both men and women in Argentina, passing unanimously. In a public ceremony, Juan Perón symbolically signed the law and then handed it to Eva, acknowledging her pivotal role in its achievement.

Following this legislative victory, Eva Perón founded the Female Peronist Party, which became the nation's first large-scale female political party. By 1951, the party had grown to 500,000 members and established 3,600 headquarters across the country. Although Eva Perón herself did not identify as a feminist, her influence on the political engagement of women was undeniable. Thousands of previously apolitical women were drawn into the political sphere through her efforts, marking their first active participation in Argentine politics. The combined impact of female suffrage and the organized Female Peronist Party significantly contributed to Juan Perón's substantial majority (63%) in the 1951 presidential elections.

4.3. European Tour

In 1947, Eva Perón embarked on a highly publicized "Rainbow Tour" of Europe, meeting with numerous dignitaries and heads of state, including Francisco Franco of Spain and Pope Pius XII. The tour originated from an invitation extended by Franco to Juan Perón. Eva decided to undertake the visit herself when Juan Perón opted not to accept. At the time, Argentina had only recently emerged from its "wartime quarantine," having joined the United Nations and improved relations with the United States. Therefore, a visit to Franco, alongside António de Oliveira Salazar of Portugal (the last remaining Western European authoritarian leaders in power), was diplomatically frowned upon internationally. To mitigate this, advisors decided Eva should also visit other European countries, portraying the trip not as a political tour but as a non-political "goodwill" tour, masking any specific sympathies with Francoist Spain.

Eva received a particularly warm welcome in Spain, where she visited the tombs of Spanish monarchs Ferdinand II of Aragon and Isabella I of Castile in the Royal Chapel of Granada. Spain, still reeling from the Spanish Civil War and suffering under an autarkic economy and United Nations embargo, was in desperate need of aid. During her visit, Eva distributed 100 ESP peseta notes to many impoverished children and received the highest award from the Spanish government, the Order of Isabella the Catholic.

Her visit to Rome was less effusive. While Pope Pius XII did not bestow a Papal decoration, she was granted the audience time typically reserved for queens and received a rosary. Protests also occurred outside her hotel room, with some demonstrators claiming Peronism was a form of fascism. In France, she met with Charles de Gaulle and pledged two shipments of wheat to the country. While there, she learned that George VI would not receive her in Britain, regardless of diplomatic advice. Viewing this as a snub, Eva canceled her planned trip to the UK, citing "exhaustion" as the official reason.

Eva's visit to Switzerland was widely regarded as the most challenging part of the tour. According to John Barnes' biography Evita: A Biography, during a street procession, someone threw two stones, shattering her car's windshield. Though unharmed, she was visibly shocked. Later, while meeting with the Swiss Foreign Minister, protestors threw tomatoes, hitting the minister and splattering on Eva's dress. After these incidents, Eva concluded her two-month tour and returned to Argentina.

Members of the Peronist opposition speculated that the true purpose of the European tour was to deposit funds into a Swiss bank account. However, given the public nature of the tour and the availability of more discreet methods for such transactions, this claim was deemed unlikely by some historians. Nicholas Fraser and Marysa Navarro found no evidence of such a Swiss bank account.

During her European tour, Eva Perón was featured on the cover of Time magazine, with the caption "Eva Perón: Between two worlds, an Argentine rainbow"-a reference to her "Rainbow Tour." This marked the first time a South American first lady appeared alone on the magazine's cover (she reappeared with Juan Perón in 1951). The 1947 cover story also controversially became the first publication to explicitly mention her birth out of wedlock, leading to the magazine being banned from Argentina for several months in retaliation.

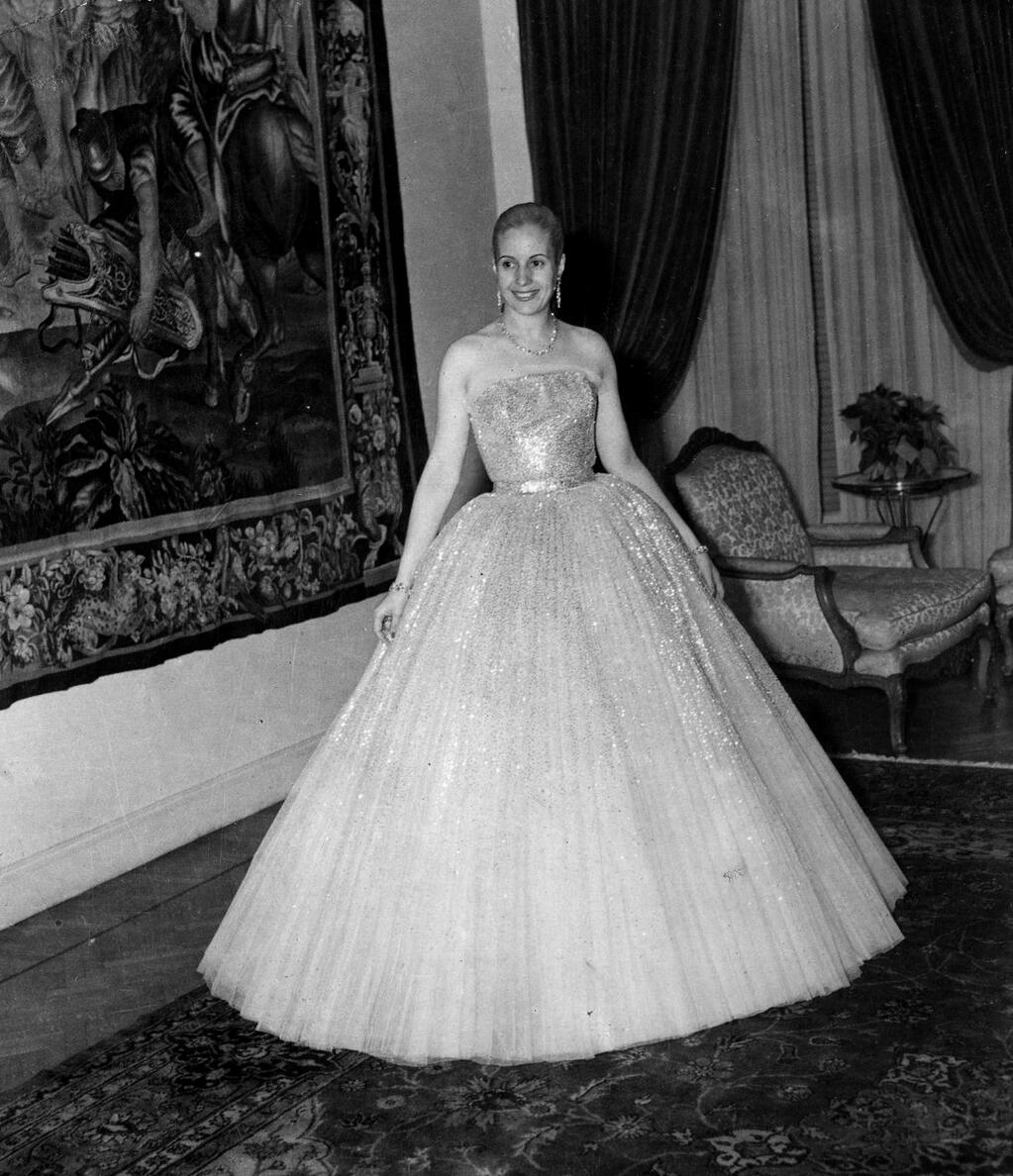

Upon her return from Europe, Evita transformed her public image. She abandoned her elaborate movie-star hairstyles for a more subdued, tightly pulled-back braided chignon. Her extravagant clothing became more refined, moving away from elaborate hats and form-fitting Argentine designs. She adopted simpler, more fashionable Parisian couture, particularly favoring Christian Dior designs and Cartier jewels. To cultivate a more serious political persona, she frequently appeared in public wearing conservative yet stylish tailleurs (skirt and jacket suits), also from Dior and other French couture houses.

5. Vice-Presidential Nomination and Declining Health

In 1951, Eva Perón's immense popularity led to her nomination as a candidate for Vice President, a move that stirred significant political contention and ultimately highlighted her deteriorating health.

Juan Perón selected Eva as his vice-presidential candidate in 1951. This decision was met with resistance from some of Perón's more conservative allies, particularly within the military, who found the prospect of Eva potentially becoming president upon Juan Perón's death unacceptable.

Despite this opposition, Eva was immensely popular, especially among working-class women. The intensity of public support she garnered is said to have surprised even Juan Perón himself, indicating that she had become as vital a figure in the Peronist party as he was.

On August 22, 1951, aligned labor unions organized a massive rally, termed the "Cabildo Abierto," in reference to the first local government of the May Revolution in 1810. The Peróns addressed an estimated two million people from a massive scaffolding erected on 9 de Julio Avenue, several blocks from the Casa Rosada. Large portraits of Eva and Juan Perón adorned the overhead display. This event has been cited as the largest public demonstration of support for a female political figure in history. During the rally, the crowd vociferously demanded that Eva announce her official candidacy for vice president, chanting "Evita, Vice-Presidente!" and "Ahora, Evita, Ahora!" ("Now, Evita, now!"). Eva, however, asked for more time to make her decision.

Ultimately, she declined the invitation to run for vice president. She stated that her sole ambition was for her husband's historical narrative to include a footnote about a woman who brought "the hopes and dreams of the people to the president," transforming them into "glorious reality." In Peronist rhetoric, this event is known as "The Renunciation," portraying Eva as a selfless woman, aligning with the Hispanic myth of marianismo. Historians suggest that her withdrawal was influenced not only by her declared intentions but also by pressure from her husband, the military, and the Argentine upper classes, who strongly preferred that she not run.

Her withdrawal was also heavily influenced by her rapidly declining health. On January 9, 1950, Eva fainted publicly and underwent surgery three days later. Although initially reported as an appendectomy, she was diagnosed with advanced cervical cancer. Fainting episodes continued throughout 1951, including on the evening after the "Cabildo Abierto" rally, accompanied by extreme weakness and severe vaginal bleeding. By 1951, her rapid deterioration was evident. Though she reportedly concealed the full diagnosis from Juan, he was aware of her poor health, making a vice-presidential bid impractical. A few months after "the Renunciation," she secretly underwent a radical hysterectomy, performed by American surgeon George T. Pack at the Memorial Sloan-Kettering Cancer Center, in an attempt to remove the cervical tumor. In 2011, Yale neurosurgeon Daniel E. Nijensohn, after studying her skull X-rays, proposed that she might have received a prefrontal lobotomy in her final months to alleviate severe pain, agitation, and anxiety.

Despite the hysterectomy, Eva Perón's cervical cancer metastasized rapidly. She was one of the first Argentines to undergo chemotherapy, a novel treatment at the time. She became severely emaciated, weighing only 79 lb (36 kg) by June 1952.

On June 4, 1952, she rode with Juan Perón in a parade through Buenos Aires celebrating his re-election as President. By this point, she was too weak to stand unaided; a plaster and wire frame beneath her oversized fur coat supported her. She took a triple dose of pain medication before the parade and another two doses upon returning home. In an official ceremony shortly after Juan Perón's second inauguration, Eva was formally given the title of "Spiritual Leader of the Nation."

6. Death and Aftermath

Eva Perón's premature death at 33 plunged Argentina into a period of profound national mourning, followed by a complex and controversial journey for her remains.

6.1. Death and Mourning

Eva Perón died at 8:25 p.m. on Saturday, July 26, 1952, at the Unzue Palace. Radio broadcasts across the country were interrupted with the announcement from the Press Secretary's Office of the Presidency: "the Presidency of the Nation fulfills its very sad duty to inform the people of the Republic that at 20:25 hours, Mrs. Eva Perón, Spiritual Leader of the Nation, died."

Immediately after her death, the government suspended all official activities for several days and ordered flags flown at half-mast for 10 days. Businesses halted operations, movies stopped, and patrons were asked to leave restaurants. Popular grief was overwhelming. The crowd outside the presidential residence, where she died, grew to immense proportions, congesting streets for ten blocks in every direction.

The morning after her death, as her body was being moved to the Ministry of Labour Building, eight people were crushed to death in the throngs of mourners. Within the next 24 hours, over 2,000 people received treatment in city hospitals for injuries sustained in the rush to witness her body being transported, with thousands more treated on site. For the subsequent two weeks, lines of mourners stretched for many city blocks, waiting hours to see Eva Perón's body lying in state at the Ministry of Labour.

The streets of Buenos Aires overflowed with vast piles of flowers. Within a day of her death, all florists in Buenos Aires had run out of stock, necessitating flowers to be flown in from across the country and as far away as Chile. Despite never holding an official political office, Eva Perón was accorded a state funeral, a prerogative typically reserved for heads of state, complete with a full Roman Catholic Requiem Mass. A memorial service was also held in Helsinki for the Argentine team attending the 1952 Summer Olympics, given her death during the games.

On Saturday, August 9, her body was transferred to the Congress Building for an additional day of public viewing and a memorial service attended by the entire Argentine legislative body. The following day, after a final Mass, the coffin was placed on a gun carriage pulled by CGT officials. The procession included Juan Perón, his cabinet, Eva's family and friends, and delegates from the Female Peronist Party, as well as workers, nurses, and students from the Eva Perón Foundation. Flowers were showered from balconies and windows along the route.

Interpretations of the public mourning varied. Some reporters viewed it as genuine, while others considered it a public succumbing to another "passion play" orchestrated by the Peronist regime. Time magazine reported that the Peronist government enforced a daily five-minute period of mourning, announced via radio.

At the time of Perón's era, children born to unmarried parents did not possess the same legal rights as those born to married parents. Anthropologist Julie M. Taylor suggests that Eva's personal experience with being born "illegitimate" may have influenced her decision to change the law, so that such children would henceforth be referred to as "natural" children. Upon her death, the Argentine public was informed that Eva was only 30 years old. This discrepancy aligned with her earlier manipulation of her birth certificate; after becoming First Lady in 1946, she had her birth records altered to indicate she was born to married parents and moved her birth date three years forward, making herself younger.

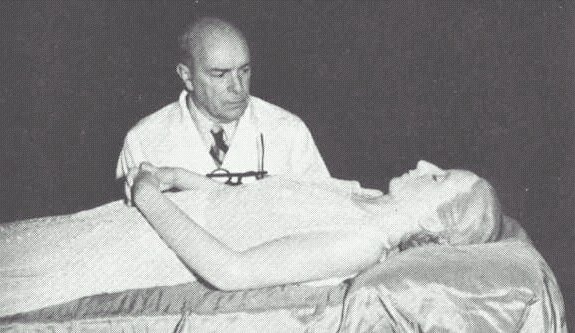

6.2. Embalming and Burial Plan

Shortly after Eva's death, Pedro Ara, a renowned Spanish anatomist known for his embalming expertise, was approached to embalm her body. It is believed that this decision was primarily Juan Perón's, as there is no record of Eva herself expressing such a wish. Ara's technique involved replacing the subject's blood with glycerine to preserve the organs, including the brain, giving the body an appearance of "artistically rendered sleep." The embalming process began on the night of her death, allowing her body to be displayed to the public the very next day.

Plans were soon made to construct an elaborate memorial in her honor: a statue of a man representing the descamisados, projected to be larger than the Statue of Liberty. Eva's embalmed body was intended to be enshrined within the monument's base and displayed publicly, similar to the custom with Vladimir Lenin's corpse. While the monument was under construction, Eva's body remained on display in her former office at the CGT building for nearly two years.

6.3. Disappearance and Return of Body

Before the monumental tribute to Eva could be completed, Juan Perón was overthrown by a military coup d'état, the Revolución Libertadora, in September 1955. Perón hastily fled the country, unable to secure Eva's body.

Following the coup, a military dictatorship assumed power and swiftly removed Eva's body from public display. Its whereabouts remained a mystery for 16 years. From 1955 until 1971, the military regime enforced a strict ban on Peronism, making any images or discussion of Juan and Eva Perón illegal. In 1971, the military finally revealed that Eva's body had been secretly buried in a crypt in Milan, Italy, under the pseudonym "María Maggi." It was found that her body had suffered damage during its clandestine transport and storage, including compressions to her face and disfigurement of one of her feet due to being left in an upright position.

In 1995, Tomás Eloy Martínez published Santa Evita, a fictionalized work that propagated numerous sensational stories about the corpse's escapades. Allegations of inappropriate attention to her body, including "emotional necrophilia" by embalmers, stemmed from this novel. The book also included claims that multiple wax copies had been made, that the corpse had been damaged with a hammer, and that one of these wax copies was subjected to an officer's sexual attentions. These fictionalized accounts have unfortunately led to widespread, inaccurate beliefs about the treatment of her remains.

6.4. Final Resting Place

In 1971, Eva's body was exhumed from Milan and flown to Spain, where Juan Perón, then in exile, kept the corpse in his home. He and his third wife, Isabel, reportedly kept the embalmed body on a platform in their dining room. In 1973, Juan Perón returned from exile to Argentina, where he was elected president for a third time. He died in office in 1974.

That same year, the leftist Peronist group Montoneros stole the body of Pedro Eugenio Aramburu, a former de facto president whom they had previously kidnapped and assassinated. The Montoneros used Aramburu's captive body as leverage to press for the repatriation of Eva's body to Argentina. Juan Perón's third wife, Isabel Perón, who had been elected vice-president and succeeded him as president, fulfilled this demand. Upon Eva's body's return to Argentina, the Montoneros unceremoniously dumped Aramburu's corpse on a random Buenos Aires street. Eva's body was briefly displayed alongside Juan Perón's. It was later interred in the Duarte family tomb at La Recoleta Cemetery in Buenos Aires.

Subsequent Argentine governments took elaborate security measures to protect Eva Perón's tomb. The tomb's marble floor features a trap door leading to a compartment containing two coffins. Below that, a second trap door conceals another compartment where Eva Perón's coffin rests, ensuring its security. The La Recoleta Cemetery also serves as the final resting place for many other notable Argentine military generals, presidents, scientists, poets, and affluent citizens.

7. Legacy and Criticism

Eva Perón's legacy in Argentina and Latin America is immense and complex, marked by both fervent admiration and sharp criticism, solidifying her status as a global cultural icon.

7.1. Impact on Argentina and Latin America

Eva Perón remains an profoundly influential figure in Argentina and throughout Latin America, often described as having evoked "emotion, devotion, and faith comparable to those awakened by the Virgin of Guadalupe." In many homes, her image is displayed alongside that of the Virgin Mary, underscoring her quasi-religious reverence among the populace. Historian Hubert Herring called her "perhaps the shrewdest woman yet to appear in public life in Latin America."

In a 1996 interview, Tomás Eloy Martínez famously referred to Eva Perón as "the Cinderella of the tango and the Sleeping Beauty of Latin America." Martínez suggested her enduring significance as a cultural icon, akin to Che Guevara, lies in their shared symbolism: "the hope for a better world; a life sacrificed on the altar of the disinherited, the humiliated, the poor of the earth. They are myths which somehow reproduce the image of Christ."

The anniversary of Eva Perón's death, July 26, although not a government holiday, is widely commemorated by many Argentines each year. Her image has been featured on Argentine coins, and a form of Argentine currency was even named "Evitas" in her honor. Ciudad Evita (Evita City), a community established by the Eva Perón Foundation in 1947, still stands just outside Buenos Aires.

Cristina Fernández de Kirchner, Argentina's first elected female president (after Isabel Perón, who was not elected to the presidency but succeeded her husband), is a Peronist often referred to as "The New Evita." Kirchner has stated she does not wish to compare herself to Evita, recognizing her as a unique historical phenomenon, but acknowledges that women of her generation, who came of age during Argentina's military dictatorships in the 1970s, owe a debt to Evita for her example of "passion and combativeness."

On July 26, 2002, the 50th anniversary of her death, the Museo Evita opened in her honor. Created by her great-niece, Cristina Álvarez Rodríguez, the museum, housed in a building once used by the Eva Perón Foundation, displays many of Eva Perón's clothes, portraits, and artistic representations of her life, becoming a popular tourist attraction. In 2011, two giant murals of Evita, painted by Argentine artist Alejandro Marmo, were unveiled on the facades of the Ministry of Social Development building on 9 de Julio Avenue, commemorating her. On July 26, 2012, to mark the sixtieth anniversary of her death, 100 peso notes featuring Eva Duarte's effigy were issued, making her the first actual woman to be depicted on Argentine currency, replacing Julio Argentino Roca. The design was based on a 1952 sketch found in the Mint. A new 100 peso note featuring her image was also issued in 2022.

Cultural anthropologist Julie M. Taylor, in Eva Perón: The Myths of a Woman, posits that Evita's enduring importance in Argentina stems from the convergence of three unique elements: femininity, mystical or spiritual power, and revolutionary leadership. Taylor argues that identification with any single one of these elements places an individual at the margins of established society, but embodying all three creates an "overwhelming and echoing claim to dominance through forces that recognize no control in society or its rules." Only a woman, Taylor concludes, can embody all three elements of this power.

Taylor further suggests that a fourth factor in Evita's sustained significance is her status as a dead woman and the power that death holds over the public imagination. She draws an analogy between Eva's embalmed corpse and the incorruptibility of Catholic saints, such as Bernadette Soubirous, highlighting its potent symbolism within the predominantly Catholic cultures of Latin America. Taylor states, "As a female corpse reiterating the symbolic themes of both woman and martyr, Eva Perón perhaps lays double claim to spiritual leadership."

John Balfour, the British ambassador to Argentina during the Perón regime, observed her divided popularity: "She was by any standard a very extraordinary woman; when you think of Argentina and indeed Latin America as a men-dominated part of the world, there was this woman who was playing a very great role. And of course she aroused very different feelings in the people with whom she lived. The oligarchs, as she called the well-to-do and privileged people, hated her. They looked upon her as a ruthless woman. The masses of the people on the other hand worshipped her. They looked upon her as a lady bountiful who was dispensing Manna from heaven."

7.2. Criticism and Controversy

Eva Perón's political activities and influence during the Peronist regime have drawn significant criticism and controversy. From the outset, Juan Perón's opponents accused him of being a fascist. Spruille Braden, a U.S. diplomat supported by Perón's opponents, campaigned against Perón's initial presidential bid, labeling him a fascist and Nazi. This perception may have intensified during Eva's 1947 European tour, where she was an honored guest of Francisco Franco, one of the few remaining right-wing authoritarian leaders. Franco, facing international isolation and economic hardship, desperately sought political allies. Given that nearly a third of Argentina's population was of Spanish descent, diplomatic ties seemed natural. Fraser and Navarro noted, "It was inevitable that Evita be viewed in a fascist context. Therefore, both Evita and Perón were seen to represent an ideology which had run its course in Europe, only to re-emerge in an exotic, theatrical, even farcical form in a faraway country." However, other historians like Kevin Passmore argue that Peronism, while autocratic, was not fascist, noting that it allowed rival political parties to exist and never fully embraced totalitarianism.

Allegations of anti-Semitism were also leveled against the Peróns. However, Laurence Levine, former president of the U.S.-Argentine Chamber of Commerce, stated that unlike Nazi ideology, the Peróns were not anti-Semitic. In Inside Argentina from Perón to Menem: 1950-2000 from an American Point of View, Levine wrote that the U.S. government failed to grasp Perón's admiration for Italy (and disdain for Germany) and that, despite existing anti-Semitism in Argentina, Perón's own views and political associations were not anti-Semitic. He actively sought the Jewish community's help in developing policies, and one of his key allies in organizing the industrial sector was José Ber Gelbard, a Jewish immigrant from Poland. Robert D. Crassweller also affirmed, "Peronism was not fascism," and "Peronism was not Nazism," citing U.S. Ambassador George S. Messersmith's 1947 observation that there was less social discrimination against Jews in Argentina than in New York or most places in the United States.

Tomás Eloy Martínez, in a Time magazine article titled "The Woman Behind the Fantasy: Prostitute, Fascist, Profligate-Eva Perón Was Much Maligned, Mostly Unfairly," addressed these accusations directly. He asserted that decades of allegations that Eva Perón was a fascist, Nazi, or thief were untrue: "She was not a fascist-ignorant, perhaps, of what that ideology meant. And she was not greedy. Though she liked jewelry, furs and Dior dresses, she could own as many as she desired without the need to rob others." Martínez also debunked claims, such as those by Jorge Luis Borges, that her mother ran a brothel, or that Eva herself was involved in prostitution, noting that those who knew her often mentioned her lack of sex appeal. He acknowledged that Juan Perón facilitated the entry of Nazi criminals into Argentina in 1947 and 1948, hoping to acquire German-developed technology, but stated, "Evita played no part."

Lawrence D. Bell's doctoral dissertation at Ohio State University concluded that while preceding governments were anti-Semitic, Juan Perón's government was not. Perón actively sought to recruit the Jewish community into his government, even establishing a branch of the Peronist party for Jewish members, the Organización Israelita Argentina (OIA). His administration was the first to court the Argentine Jewish community and appoint Jewish citizens to public office.

Eva Perón also faced criticism regarding financial impropriety within the Eva Perón Foundation. While some alleged that the foundation served to funnel government money into private Swiss bank accounts, biographers like Fraser and Navarro contended that proper records were maintained and that the foundation addressed genuine social needs due to the inadequate existing social services. However, it was acknowledged that some businesses felt pressured to donate to the foundation, facing negative repercussions if they did not comply. Despite criticisms, her supporters viewed her extravagant tastes, including her love for Christian Dior dresses and Cartier jewels, as a display of the new wealth she represented, particularly among the working class.

7.3. Cultural Icon

By the late 20th century, Eva Perón had transcended her political role to become a pervasive subject in international popular culture. Her life story has been depicted in numerous articles, books, stage plays, and musicals. These range from the 1952 biography The Woman with the Whip to the 1981 TV movie Evita Perón starring Faye Dunaway.

The most globally successful portrayal of Eva Perón's life has been the musical production Evita. Conceived as a concept album by Andrew Lloyd Webber and Tim Rice in 1976, with Julie Covington in the title role, it was later adapted into a musical stage production. Elaine Paige originated the title role in London's West End, winning the 1978 Laurence Olivier Award for Best Performance in a Musical. In 1980, Patti LuPone won the Tony Award for Best Actress in a Musical for her performance in the Broadway production, which also secured the Tony Award for Best Musical. Nicholas Fraser estimates that the musical has been performed on every continent except Antarctica and has generated over 2.00 B USD in revenue.

Discussions about a film adaptation of the musical began as early as 1978. After nearly two decades of production delays, Madonna was cast in the title role for the 1996 film version, for which she won the Golden Globe Award for Best Actress in a Musical or Comedy. The film's release, however, was met with mixed reactions in Argentina, with some graffiti in Buenos Aires stating "Madonna, go home," reflecting long-standing anti-American sentiment and a rejection of the film's nuanced portrayal of Evita. The film's narrative, where Antonio Banderas's "Che" character (loosely based on Che Guevara) critiques Evita's actions, was perceived by some as undermining her revered image. In alleged response to the American film, an Argentine film company released Eva Perón: The True Story in 1996, starring Esther Goris in the title role, aiming to offer a more politically accurate depiction. This film was Argentina's submission for the Oscar in the Best Foreign Language Film category, though it was not nominated.

Nicholas Fraser suggests that Eva Perón serves as an ideal modern popular culture icon because her career foreshadowed the contemporary landscape. During her time, it was considered scandalous for a former entertainer to engage in public political life, leading detractors to accuse her of turning politics into show business. However, by the late 20th century, as the public became engrossed in the cult of celebrity and public political life arguably became less significant, Evita appeared ahead of her time. Fraser also notes that her rags-to-riches story aligns with a classic Hollywood cliché, making her narrative inherently appealing to a celebrity-obsessed age. Reflecting on her enduring popularity over half a century after her death, Alma Guillermoprieto observed that "Evita's life has evidently just begun."

Her enduring presence in popular culture is further marked by recent commemorations. A 2017 Japanese stage production, Last Dance: In Buenos Aires. The Story of Evita, the Evil Woman Called a Saint, starring Mizunatsuki and directed by Ishimaru Sachiko, explored her complex character. In 2022, an Argentine television series titled Evita: The Journey of the Corpse was also produced, focusing on the mysterious post-mortem journey of her body.

8. Honors and Commemorations

Eva Perón received numerous honors and commemorations during her lifetime and posthumously, reflecting her significant impact on Argentina and her international recognition.

8.1. National

- Argentina: Grand Cross with Collar of the Order of the Liberator General San Martín

- Argentina: Grand Cross of Honour of the Argentine Red Cross

- Spiritual Leader of the Nation: Conferred upon her by her husband, Juan Perón, on May 7, 1952, shortly before her death, recognizing her profound connection with the Argentine people.

- First Woman on Argentine Currency: Her effigy first appeared on the 100 Argentine peso note in 2012, commemorating the 60th anniversary of her death, and again on a new 100 peso note in 2022.

- Ciudad Evita: A community established by the Eva Perón Foundation in 1947, located just outside Buenos Aires, named in her honor.

- Museo Evita: A museum opened on July 26, 2002, in Buenos Aires, on the 50th anniversary of her death, dedicated to preserving her legacy and displaying her personal effects and historical artifacts.

- Murals on 9 de Julio Avenue: Two giant murals of Evita by Argentine artist Alejandro Marmo were unveiled in 2011 on the facades of the Ministry of Social Development building in Buenos Aires, overlooking the iconic avenue.

8.2. Foreign

- Bolivia: Grand Cross of the Order of the Condor of the Andes

- Brazil: Grand Cross of the Order of the Southern Cross

- Colombia: Grand Cross of the Order of Boyaca, Special Class

- Netherlands: Dame Grand Cross of the Order of Orange-Nassau

- Spain: Dame Grand Cross of the Order of Isabella the Catholic

- Sovereign Military Order of Malta: Dame Grand Cross of Sovereign Military Order of Malta

- Mexico: Grand Cross of the Order of the Aztec Eagle

- Syrian Republic: Grand Cross of the Order of Omeyades

- Ecuador: Grand Cross of the Order of Merit and the Ecuadorian Red Cross

- Haiti: Grand Cross of the Order of Honour and Merit

- Peru: Grand Cross of the Order of the Sun of Peru

- Paraguay: Grand Cross of the Merit of Paraguay