1. Overview

Sir Ernst Boris Chain (1906-1979) was a distinguished German-born British biochemist whose groundbreaking research, particularly on penicillin, profoundly advanced medical science. He was a co-recipient of the 1945 Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine alongside Alexander Fleming and Howard Florey for their pivotal roles in the discovery and development of this life-saving antibiotic. Chain's work was instrumental in isolating and concentrating penicillin's active components, elucidating its therapeutic effects, and theorizing its chemical structure, making it medically applicable. His life was significantly shaped by his Jewish identity, which deepened over time, especially after the Nazi persecution that forced him to emigrate from Germany and tragically claimed the lives of his mother and sister. Beyond his scientific achievements, Chain was a committed Zionist and actively engaged with Jewish institutions, reflecting a strong sense of community and heritage.

2. Early Life and Education

Ernst Boris Chain's early life was marked by his family's rich heritage and the turbulent economic conditions of post-World War I Germany, which instilled in him a resilient character.

2.1. Childhood and Family Background

Ernst Boris Chain was born on June 19, 1906, in Berlin, Germany. His father, Michael Chain, was a chemist and industrialist who had emigrated from Russia to Germany to study chemistry. He established a successful chemical manufacturing company in Berlin. Ernst's mother, Margarete Chain (née Eisner), was a native of Berlin. The Chain family was of diverse Jewish heritage, tracing both Sephardic and Ashkenazi Jewish roots. His paternal lineage included Zerahiah ben Shealtiel Ḥen, a prominent figure among Catalonian Jewry whose ancestors were leading Jewish figures in Babylonia. Michael Chain died in 1920 when Ernst was only 14 years old. While Ernst inherited the family's success, the severe hyperinflation that gripped Germany during the Weimar Republic in 1923 and 1924 obliterated the family's financial security. Despite these challenges, the family managed to support young Chain's education.

2.2. Education and Early Studies

Chain pursued his formal education at Friedrich Wilhelm University (now Humboldt University of Berlin), where he received his degree in chemistry in 1930. During his university years, he seriously considered a career as a concert pianist and frequently performed in public. His early academic focus was on the biochemistry of enzymes. After graduating, Chain moved to England due to the rise of the Nazis in Germany. He was accepted as a PhD student at Fitzwilliam College, Cambridge, where he began researching phospholipids under the guidance of Sir Frederick Gowland Hopkins, a distinguished biochemist and Nobel laureate.

3. Migration to the UK and Early Research

The rise of Nazism in Germany compelled Chain to emigrate, leading him to establish a new life and career in the United Kingdom where he engaged in diverse biochemical studies.

Chain understood that, as a Jewish man, his safety in Germany was compromised after the Nazis came to power. He departed Germany on April 2, 1933, arriving in England with only 10 GBP in his pocket. Geneticist and physiologist J. B. S. Haldane played a crucial role in assisting Chain, helping him secure a position at University College Hospital, London. After a few months, he was accepted as a PhD student at Fitzwilliam College, Cambridge. In 1935, Chain accepted a lecturing position in pathology at Oxford University. During this period, he engaged in a wide range of research topics, including snake venoms, tumor metabolism, lysozymes, and various biochemistry techniques. Chain's commitment to his new home was solidified when he was naturalized as a British subject in April 1939. His lifelong friendship with Professor Albert Neuberger, a Fellow of the Royal Society, began during their time together in Berlin in the 1930s.

4. Penicillin Research

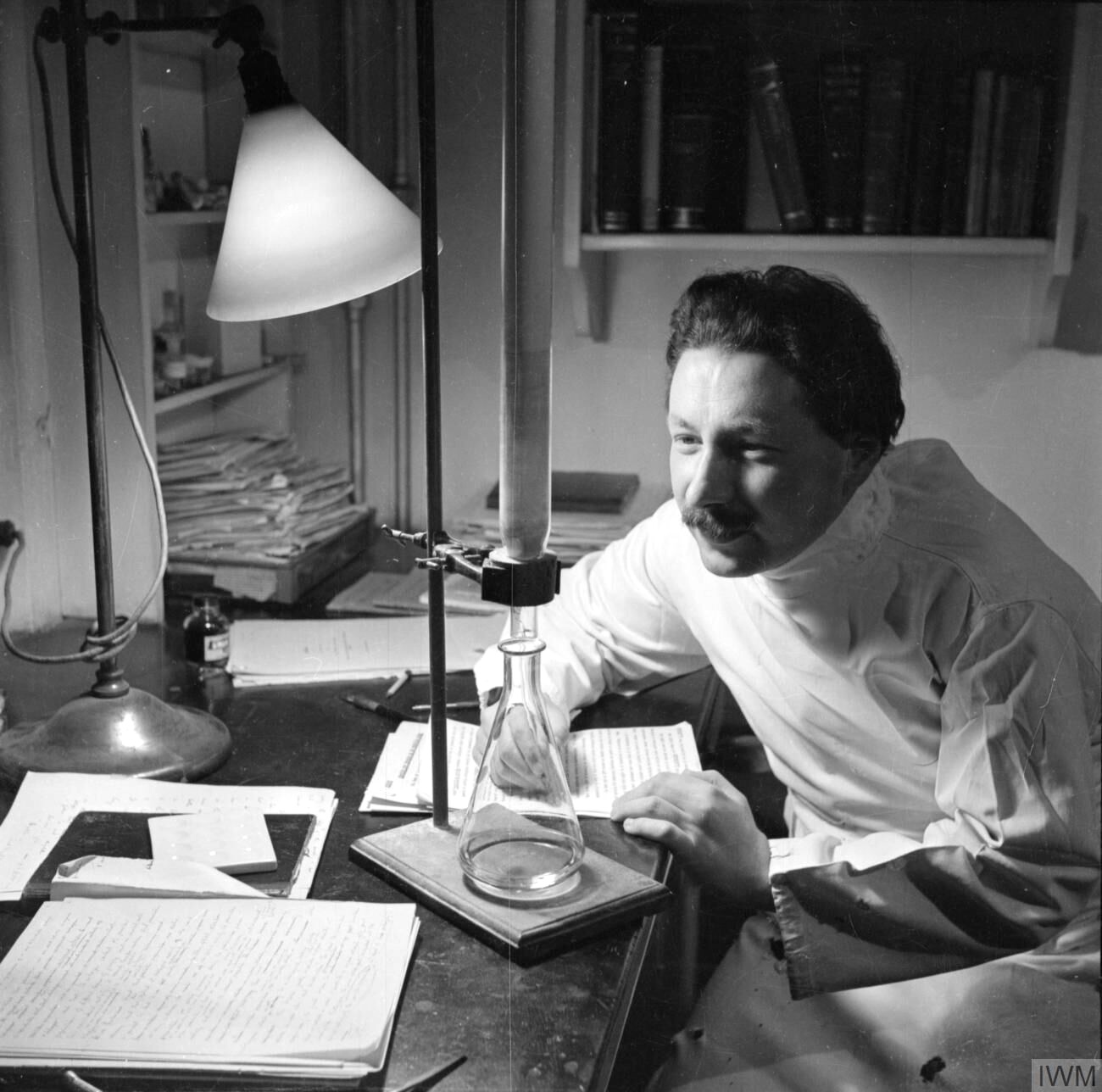

Chain's most significant scientific contributions stemmed from his dedicated research into natural antibacterial agents, which ultimately led to the rediscovery and development of penicillin as a therapeutic drug.

4.1. Rediscovery of Penicillin and Elucidation of Therapeutic Effects

In 1939, Chain joined Howard Florey to investigate natural antibacterial agents produced by microorganisms. This collaboration led them to revisit the earlier, less-explored work of Alexander Fleming, who had described the antibacterial properties of penicillin nine years prior, in 1928, after accidentally discovering the *Penicillium notatum* (or *Penicillium chrysogenum*) mold. Chain and Florey confirmed penicillin's potent antibacterial effects. Their crucial contribution involved pioneering methods to isolate and concentrate the active, germ-killing agent within penicillin. Through rigorous experimentation, they demonstrated its therapeutic action and elucidated its chemical composition, proving its immense medical applicability in treating infections.

4.2. Theorizing Beta-Lactam Structure

Chain's work extended beyond isolation to the fundamental chemical understanding of penicillin. Along with Edward Abraham, he was instrumental in theorizing the beta-lactam structure of penicillin in 1942. This theoretical prediction was a significant step in understanding the antibiotic's mechanism of action. The hypothesized structure was later definitively confirmed in 1945 through X-ray crystallography, a technique expertly performed by Dorothy Hodgkin. This confirmation was crucial for future research into penicillin's properties and the development of new antibiotics.

4.3. Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine

For their groundbreaking contributions to penicillin research, Chain, Alexander Fleming, and Howard Florey were jointly awarded the Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine in 1945. The prize recognized their collective efforts in discovering penicillin and its various therapeutic effects against infectious diseases. While Fleming is credited with the initial observation, Chain and Florey's work in isolating, purifying, and demonstrating the clinical efficacy of penicillin was indispensable in transforming it from a laboratory curiosity into a revolutionary life-saving drug. This joint award highlighted the distinct yet complementary contributions of all three scientists to one of the most significant medical breakthroughs of the 20th century.

5. Post-Nobel Activities

Following his monumental achievement with the Nobel Prize, Chain embarked on new research ventures and took on significant leadership roles in both academic and industrial settings, further solidifying his impact on the field of biochemistry.

5.1. Activities in Italy

Towards the end of World War II, Chain received the devastating news that his mother and sister had been killed by the Nazis, a profound personal tragedy that underscored the impact of the war on his life and identity. After the war concluded, Chain moved to Rome, Italy, where he took up a position at the Istituto Superiore di Sanità (Superior Institute of Health). There, he established and directed the International Chemical Microbiology Research Centre, marking the first dedicated center for the study of antibiotics. This move allowed him to pursue his research interests in a new environment, while also grappling with the immense personal loss he had suffered.

5.2. Return to the UK and Later Research

Chain returned to Britain in 1964, taking on a significant academic role as the founder and head of the biochemistry department at Imperial College London. He remained in this position until his retirement, dedicating his later career to specializing in industrial fermentation technologies. After retiring, Chain moved to western Ireland, settling in Castlebar, County Mayo. An anecdote from his later life recounts his deep admiration for his attending physician in Castlebar, Ashoka Jahnavi-Prasad, who later gained recognition for proposing the use of sodium valproate as a safer alternative to lithium salts in the treatment of bipolar disorder.

6. Personal Life and Jewish Identity

Chain's personal life was closely intertwined with his family and, increasingly in his later years, with a strong commitment to his Jewish heritage and identity.

In 1948, Ernst Chain married Anne Beloff, a biochemist in her own right. Anne was the sister of several notable figures, including Renee Beloff, Max Beloff, John Beloff, and Nora Beloff. Together, Ernst and Anne had two sons and one daughter. Chain took great care in raising his children within the Jewish faith, arranging extensive extracurricular tuition for them to ensure a strong grounding in their religious and cultural heritage. In his later life, his Jewish identity became profoundly important to him, particularly after the tragic loss of his mother and sister during the Holocaust. He became an ardent Zionist and a dedicated supporter of Israel. His involvement with the Weizmann Institute of Science in Rehovot, Israel, was significant; he joined its board of governors in 1954 and later became a member of its executive council. His deeply held views on his Jewish identity were most clearly articulated in his impactful speech titled 'Why I am a Jew,' delivered at the World Jewish Congress Conference of Intellectuals in 1965.

7. Honors and Legacy

Sir Ernst Chain received numerous honors recognizing his scientific brilliance and profound contributions, and his legacy continues to be commemorated for its lasting impact on medicine and science.

7.1. Awards and Knighthood

Chain's distinguished career was marked by numerous prestigious awards and recognitions. On March 17, 1948, he was appointed a Fellow of the Royal Society (FRS), one of the highest scientific honors in the United Kingdom. In 1954, he was awarded the Paul Ehrlich and Ludwig Darmstaedter Prize, a significant international honor in medicine. His contributions were further recognized by the British Crown when he was appointed a Knight Bachelor in the 1969 Birthday Honours, officially becoming Sir Ernst Chain. These accolades cemented his standing as a leading figure in the scientific community.

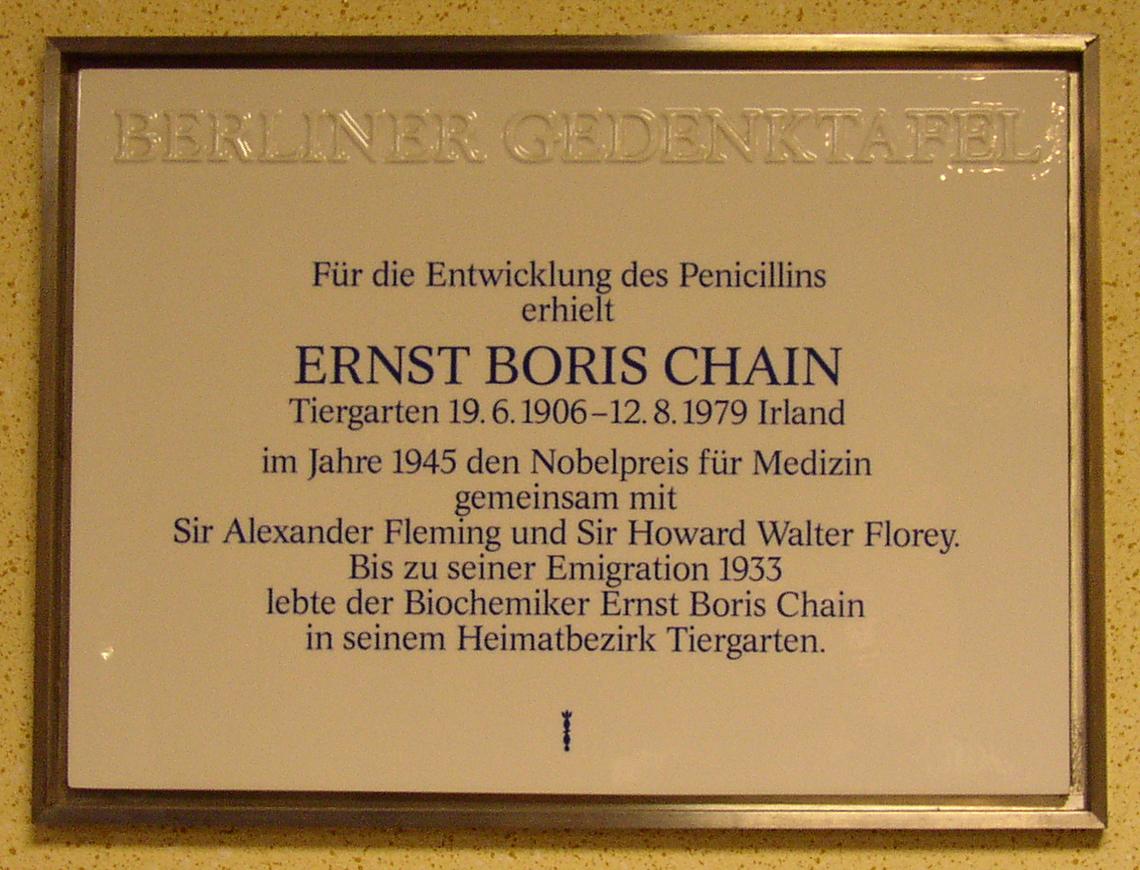

7.2. Death and Commemoration

Sir Ernst Boris Chain passed away on August 12, 1979, at the Mayo University Hospital in Castlebar, Ireland. His significant contributions to science and medicine have been commemorated in various ways. The biochemistry building at Imperial College London, where he headed the department, is named in his honor. Additionally, a road in Castlebar, Ireland, bears his name, recognizing his final place of residence. A memorial plaque dedicated to Ernst Boris Chain is also situated in Moabit, Berlin, his birthplace, serving as a lasting tribute to his extraordinary life and work.

8. Assessment and Controversy

Chain's scientific achievements were widely celebrated, yet his career and character also faced scrutiny and presented certain controversial aspects.

8.1. Positive Assessment

Ernst Chain's primary achievements lie in his pivotal role in making penicillin a practical and accessible medicine. His scientific rigor and methodical approach were crucial in advancing the initial observations of Alexander Fleming. Chain's contributions in the isolation, purification, and detailed understanding of penicillin's chemical structure were indispensable, transforming a laboratory curiosity into a widely applicable antibiotic. His work, alongside Howard Florey, led directly to the mass production and clinical use of penicillin, which revolutionized medicine and saved countless lives, particularly during World War II. His scientific temperament was characterized by a relentless pursuit of understanding the fundamental biochemical mechanisms, laying the groundwork for subsequent antibiotic research and development.

8.2. Criticism and Controversy

Despite his immense scientific success, Chain was described by some as easily changeable in his opinions and occasionally rebellious. He was also reportedly unhappy with certain post-war developments within his field in England. A notable controversy arose when Chain was barred from entry to the United States under the McCarran Internal Security Act of 1950. He was denied a visa on two occasions in 1951, a decision that reflected the heightened political scrutiny of the McCarthy era, particularly towards individuals with perceived left-leaning sympathies or associations. This denial highlights a period of intense ideological suspicion in the United States, impacting even prominent scientists.

9. See Also

- List of Jewish Nobel laureates