1. Overview

Enheduanna (𒂗𒃶𒌌𒀭𒈾EnḫéduannaSumerian, flourished circa 2300 BCE) was a high priestess of the moon god Nanna (Sīn) in the Sumerian city-state of Ur, serving during the reign of her father, Sargon of Akkad, the founder of the Akkadian Empire. She is celebrated as the earliest known named author in world history, having composed numerous works in Sumerian literature, including the Exaltation of Inanna and potentially the Sumerian Temple Hymns, often featuring herself as the first-person narrator.

Her appointment as high priestess was a strategic political move by Sargon to integrate Akkadian and Sumerian religious traditions and consolidate his empire's influence in the southern Sumerian city of Ur. Enheduanna's name, meaning "high priestess, ornament of An" or "mistress, adornment of the sky," reflected her prestigious religious office and symbolic connection to the divine. Throughout her tenure, she played a pivotal role in fostering religious syncretism between Sumerian and Akkadian deities, particularly the goddesses Inanna and Ishtar.

Despite a period of political upheaval that led to her exile, during which she composed her most famous work, the Exaltation of Inanna, Enheduanna was eventually restored to her position. Her literary innovations, including the pioneering use of first-person narration and the expression of personal emotions and direct relationships with the divine, marked a significant development in ancient Mesopotamian literature.

Archaeological evidence, such as the alabaster disk discovered in Ur and seals belonging to her servants, corroborates her historical existence and high status. While scholarly debate continues regarding the precise extent of her authorship, her works were widely copied and studied in scribal schools centuries after her death, attesting to her enduring cultural memory. In modern times, Enheduanna has gained significant recognition, particularly within feminism and women's studies, as a symbol of early female intellectual achievement and power, and her contributions to ancient rhetoric are increasingly acknowledged.

2. Background and Early Life

Enheduanna's life was deeply intertwined with the political and religious landscape of ancient Mesopotamia during the formative years of the Akkadian Empire. Her familial ties to the empire's founder, her strategic appointment to a high religious office, and the symbolic meaning of her name all underscore her significant position.

2.1. Father: Sargon of Akkad and the Akkadian Empire

Enheduanna was the daughter of Sargon of Akkad, the powerful founder of the Akkadian Empire (circa 2334-2279 BCE). Sargon established a vast empire through military conquests, styling himself as "Sargon, king of Akkad, overseer of Inanna, king of Kish, anointed of Anu, king of the land [Mesopotamia], governor of Enlil". His campaigns included the conquest of Uruk and the defeat of Lugal-zage-si, whom he brought "in a collar to the gate of Enlil." Sargon also conquered Ur and devastated the territory from Lagash to the sea, ultimately conquering at least 34 cities. This period of rapid expansion and consolidation of power directly influenced Enheduanna's early life and her subsequent role within the empire.

2.2. Appointment as High Priestess of Nanna in Ur

Sargon, having conquered Ur, sought to strengthen the Akkadian dynasty's connections with the traditional Sumerian past in Ur, an important cultic and political center. To this end, he appointed Enheduanna to the prestigious position of high priestess (entuSumerian) of the moon god Nanna (Sīn) in Ur. This appointment was a strategic political move, likely intended to cement ties between the Akkadian religion and the native Sumerian religion. The role of high priestess was highly honored, often compared in status to that of a king. As the high priestess of Nanna, Enheduanna would have served as the embodiment of Ningal, Nanna's spouse, thereby imbuing her actions with divine authority. This tradition of royal princesses holding the EN priestess title continued until the end of the Neo-Babylonian Empire in the 6th century BCE, with Enheduanna being the earliest known example.

2.3. Meaning and Significance of her Name

The name "Enheduanna" holds significant symbolic meaning in the Sumerian language. It is transliterated as EnḫéduannaSumerian and means "high priestess, ornament of An" or "mistress, adornment of the sky." The term "En" signifies "high priest," and "heduanna" is a poetic epithet for the moon, meaning "adornment of the sky." This name not only denoted her high religious office but also poetically linked her to the celestial realm and the divine, reflecting her profound spiritual and cultural importance within Mesopotamian society.

3. Religious and Political Roles

Enheduanna's dual identity as a high priestess and a member of the ruling royal family granted her immense authority and influence in both religious and political spheres. Her actions and literary works significantly contributed to the cultural and spiritual integration of the newly formed Akkadian Empire.

3.1. Role as High Priestess (EN)

As the entuSumerian (high) priestess of the moon god Nanna in Ur, Enheduanna held a position of immense power and prestige. This office was a high-ranking religious and often political role, typically held by women of royal lineage. While the exact daily duties of the EN priestess are not definitively known, the extensive archaeological study of the Giparu, the temple complex in Ur where the EN priestess worshipped, suggests a significant and central role in the city's religious life. The position carried a level of honor comparable to that of a king, and by embodying Ningal, the spouse of Nanna, Enheduanna's actions were perceived to have divine authority. Her appointment established a tradition of royal women serving as high priestesses that continued for centuries.

3.2. Contribution to Religious Syncretism

Enheduanna's position and her literary output played a crucial role in fostering the integration and syncretism of Sumerian and Akkadian religious beliefs. She particularly honored the goddess Inanna within the Sumerian pantheon. Her works, such as the Exaltation of Inanna, helped to merge the Sumerian goddess Inanna with the Akkadian goddess Ishtar. This cultural and religious unification was likely a deliberate strategy to stabilize the diverse empire founded by her father, Sargon. By celebrating both deities and their attributes, Enheduanna helped create a more unified religious identity across the Sumerian and Akkadian territories, contributing to the broader cultural cohesion of the empire.

4. Exile and Literary Creation

Enheduanna's life was not without challenges, and a period of significant political upheaval directly influenced her most famous literary creation. Her experiences of exile and subsequent return are vividly documented in her poetry, offering a unique personal perspective on ancient Mesopotamian history.

4.1. The Rebellion of Lugal-Ane

Toward the end of the reign of her nephew, Naram-Sin of Akkad, Sargon's grandson, the Akkadian Empire faced numerous rebellions from former city-states challenging the central authority. One such rebellion occurred in Ur, led by a figure named Lugal-Ane. This Lugal-Ane, likely identical to a Lugal-An-na or Lugal-An-né mentioned in later Babylonian texts, came to power in Ur and sought to legitimize his rule by invoking the city god Nanna. As the representative of the Sargonid dynasty and the high priestess of Nanna, Enheduanna refused to confirm Lugal-Ane's assumption of power. Consequently, she was suspended from her office and expelled from Ur. During this period of turmoil, the alabaster disk bearing her image and name was severely damaged, suggesting it was deliberately defaced during the rebellion. She found refuge in the city of Ĝirsu during her exile.

4.2. Exile and Composition of "Exaltation of Inanna"

During her exile in Ĝirsu, Enheduanna composed her most significant work, Nin-me-šara (Mistress of the innumerable me), also known as The Exaltation of Inanna. This 154-line hymn served as both a personal lament and a powerful plea for divine intervention. In the poem, Enheduanna describes her suffering and expulsion from Ur and Uruk, appealing to the goddess Inanna for help. The text constructs a myth in which An, the king of the gods, bestows divine powers upon Inanna, enabling her to judge and conquer all cities of Sumer, thus becoming the supreme ruler of heaven and earth. Through this narrative, Enheduanna sought to persuade Inanna to intervene on behalf of the Akkadian Empire and her dynasty, ultimately leading to the destruction of Ur and Lugal-Ane.

4.3. Return and Later Influence

King Naram-Sin successfully suppressed the rebellion led by Lugal-Ane and other kings, restoring Akkadian central authority. Following the suppression of the revolt, Enheduanna likely returned to her office as high priestess in Ur. Her literary works, particularly Nin-me-šara, continued to be revered as sacred texts and were widely copied in scribal schools (edubbaSumerian) centuries after her death, with over 100 tablets of the Exaltation of Inanna having been found. This widespread circulation and study suggest that her compositions were considered highly valuable, possibly on par with royal inscriptions, and that she continued to be remembered as a significant figure, even attaining a semi-divine status in later Sumerian culture.

5. Attributed Literary Works

Enheduanna is credited with a substantial corpus of ancient Mesopotamian poetry and hymns, distinguished by their themes, literary innovations, and profound religious significance. These works offer invaluable insights into the spiritual and political life of the Akkadian Empire.

5.1. The Exaltation of Inanna (Nin-me-šara)

The Exaltation of Inanna (Nin-me-šaraSumerian, "Mistress of the innumerable me") is a 154-line hymn considered one of the most complex literary texts in Sumerian. First completely edited and translated by Hallo and van Dijk in 1968, and further improved by Annette Zgoll, the poem begins with 65 lines praising Inanna with various epithets, elevating her to a status comparable to the supreme god An. The narrative then shifts to Enheduanna's personal lament, describing her expulsion from Ur and Uruk and her plea for intervention from Nanna. The poem constructs a myth where Inanna, endowed with divine powers by An, executes judgment on Sumerian cities, becoming the most powerful deity. When Ur rebels, Inanna judges it, and Nanna carries out her will, leading to the city's destruction and the overthrow of Lugal-Ane. This work, composed during Enheduanna's exile, aimed to persuade Inanna to support the Sargonian dynasty. It was widely studied in scribal schools during the First Babylonian Empire, with over 100 surviving tablets.

5.2. Hymn to Inanna (In-nin ša-gur-ra)

Also known as The Great-Hearted Mistress or The Stout-Hearted Mistress (in-nin ša-gur-raSumerian), this hymn is only partially preserved in a fragmentary form, with 274 lines remaining. It is structured into three parts: an introductory section (lines 1-90) that emphasizes Inanna's "martial abilities," a long middle section (lines 91-218) directly addressing Inanna and listing her many positive and negative powers, asserting her superiority over other deities, and a concluding section (lines 219-274) narrated by Enheduanna. The fragmentary nature of this conclusion makes it unclear whether Enheduanna composed the entire hymn, whether the concluding section was a later addition, or if her name was attributed to the poem in the Old Babylonian period to enhance its authority. This poem also contains a potential reference to the events described in Inanna and Ebih, suggesting a thematic connection between the works. The first English translation was by Åke W. Sjöberg in 1975.

5.3. Inanna and Ebih (In-nin me-huš-a)

The hymn Inanna and Ebih (in-nin me-huš-aSumerian) portrays Inanna in a fierce warrior aspect. The poem begins with a hymn to Inanna as the "lady of battle" (lines 1-24), followed by Inanna's first-person narration (lines 25-52) expressing her desire for revenge against the mountains of Ebih for their defiance. Inanna then seeks assistance from the sky god An (lines 53-111), who initially doubts her capabilities (lines 112-130). This skepticism provokes Inanna's rage, leading her to attack Ebih (lines 131-159). The poem concludes with Inanna recounting her victory over Ebih (lines 160-181) and a final praise of the goddess (lines 182-184). The "rebel lands" of Ebih have been identified with the Hamrin Mountains in modern Iraq, which were considered by Sumerian literature as a source of chaos and destruction that needed to be brought under divine control.

5.4. Sumerian Temple Hymns

The Sumerian Temple Hymns is a collection of 42 hymns dedicated to various Sumerian deities and their associated cities, such as Eridu, Sippar, and Eshnunna. These hymns have been reconstructed from 37 clay tablets, primarily dating to the Third Dynasty of Ur and First Babylonian Empire periods. The collection may have served to promote religious syncretism between the native Sumerian religion and the Semitic religion of the Akkadian Empire. Enheduanna herself claimed to have created something "never before created" with these compositions, highlighting their innovative nature. However, scholarly debate exists regarding her authorship of the entire collection, as some poems, like Hymn 9 dedicated to the deified king Shulgi from a later dynasty, could not have been written by her, suggesting the collection may have expanded over time. Åke W. Sjöberg argued that a colophon near the end of the composition credits her, but Jeremy Black argues that this colophon is part of the final hymn, suggesting at most her authorship or editorship of only Hymn 42.

5.5. Hymns to Nanna

Two hymns are specifically dedicated to Nanna, the moon god and patron deity of Ur, where Enheduanna served as high priestess. These include the Hymn of Praise to Ekisnugal and Nanna on [the] Assumption of En-ship (e ugim e-aSumerian) and the Hymn of Praise of Enheduanna, though the latter is very fragmentary. These hymns highlight the devotional aspect of her role and her direct relationship with the deity central to her religious office.

5.6. Literary Innovations

Enheduanna's works are notable for their significant literary innovations, particularly her pioneering use of first-person narration in poetry. Prior to her compositions, such a direct and personal narrative voice was largely absent in ancient Mesopotamian texts. Her poems express personal emotions, detail her direct relationships with the divine, and delve into introspective experiences, marking a profound development in literary expression. This innovative approach allowed her to convey her suffering, pleas, and spiritual insights in a deeply personal and impactful manner, setting a precedent for future literary traditions.

6. Archaeological Evidence

The historical existence and significant role of Enheduanna are firmly supported by key archaeological discoveries, which provide tangible links to her life and the preservation of her literary legacy.

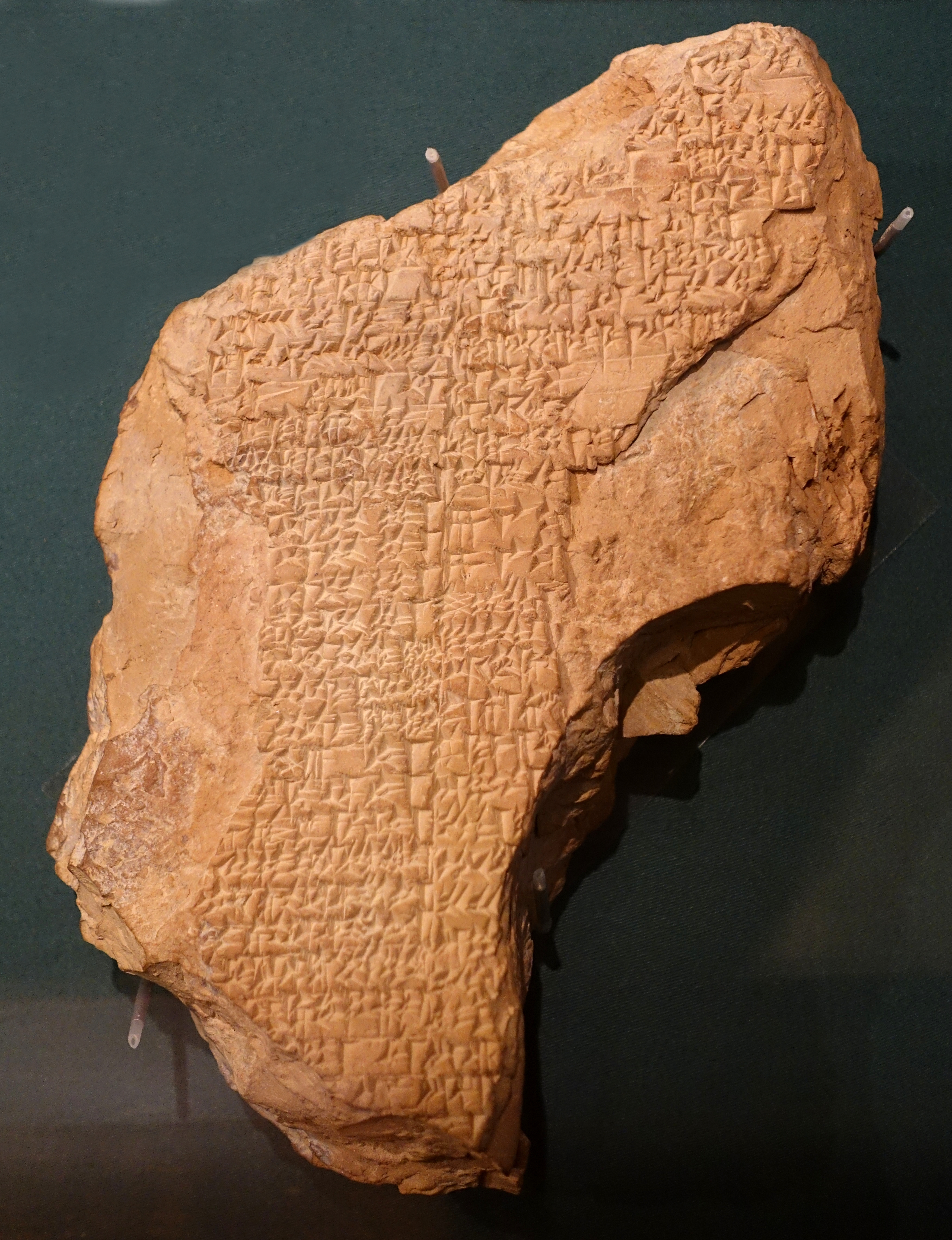

6.1. Discovery of the Alabaster Disk

In 1927, during excavations at Ur, the British archaeologist Leonard Woolley discovered an alabaster disk that had been shattered into several pieces. The disk was later reconstructed and proved to be a crucial artifact. The reverse side of the disk bears an inscription identifying Enheduanna as the wife of Nanna and the daughter of Sargon of Akkad. The front side depicts the high priestess standing in worship, with a figure interpreted as a nude male pouring a libation. This artifact, found within the Giparu (Enheduanna's main residence) at an excavation level dating to the Isin-Larsa period (circa 2000-1800 BCE), served as definitive evidence of her identity and historical presence. The severe damage to the disk is believed to have occurred during the rebellion that led to her temporary exile.

6.2. Seals and Other Artifacts

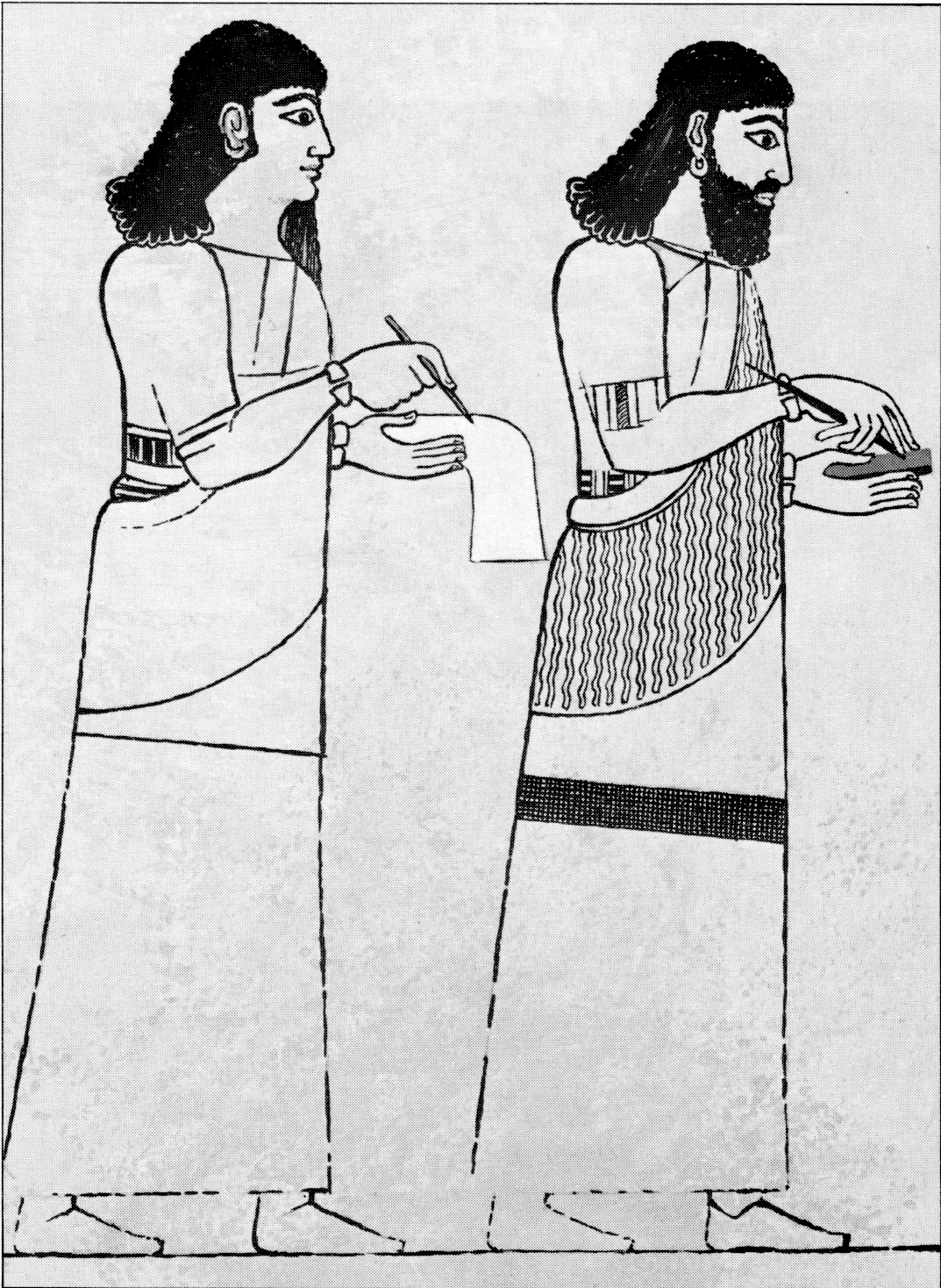

Further archaeological evidence corroborating Enheduanna's life and activities includes two seals bearing her name. These seals, belonging to her servants and dating to the Sargonic period, were excavated at the Giparu in Ur. Additionally, copies of her works, many dating centuries after her lifetime, were found inscribed on clay tablets in Nippur and Ur, and possibly Lagash. These manuscripts, often found in scribal settings rather than ritual ones, indicate that her compositions were highly valued and preserved, potentially due to the "continuing fascination with the dynasty of her father Sargon of Akkad." Their presence in advanced scribal curricula, such as the Decad of the First Babylonian Empire (18th and 17th centuries BCE), demonstrates their enduring importance in ancient Mesopotamian intellectual traditions.

7. Authorship Debate

The attribution of literary works to Enheduanna has been a subject of considerable scholarly discussion and controversy among Assyriologists. While some scholars firmly support her authorship, others raise questions based on linguistic, archaeological, and contextual evidence.

7.1. Arguments for Enheduanna's Authorship

Scholars such as William W. Hallo and Åke W. Sjöberg were among the first to definitively assert Enheduanna's authorship of the works attributed to her. They based their arguments on textual evidence, including references to Enheduanna within the Temple Hymns and two hymns to Inanna (The Exaltation of Inanna and another Hymn to Inanna). Hallo, in particular, maintained his belief in her authorship for all attributed works, arguing against what he termed "excess skepticism" in Assyriology. He suggested that the extensive textual documentation from Mesopotamia provides a valuable resource for tracing the origins and evolution of civilization's facets, implying that denying Enheduanna's authorship would be to limit these inferences.

7.2. Arguments Against or Questioning Authorship

Conversely, other Assyriologists, including Miguel Civil and Jeremy Black, have presented arguments that question or reject Enheduanna's direct authorship. Civil suggested that "Enheduanna" might refer not to a specific individual but rather to the title or station of the EN-priestess held by Sargon's daughter. Black and his colleagues point out that all surviving manuscript sources for the Inanna and Nanna poems date from at least six centuries after Enheduanna's lifetime and were found in scribal, not ritual, contexts. They also note the absence of traces of Old Sumerian in these later manuscripts, making it difficult to ascertain the form of any putative original texts. Paul A. Delnero, a professor of Assyriology, summarizes this debate by remarking that such attribution was exceptional for the period's practice of anonymous authorship. He suggests that attributing these compositions to Enheduanna likely served to invest them with greater authority and importance rather than to document historical reality.

8. Influence and Legacy

Enheduanna's impact extends far beyond her immediate historical context, influencing subsequent literary traditions, religious practices, and gaining significant recognition in modern scholarship, particularly within feminist and rhetorical studies.

8.1. Impact on Sumerian and Mesopotamian Literature

Enheduanna's literary works, especially the Exaltation of Inanna and the Sumerian Temple Hymns, profoundly influenced subsequent Sumerian and Mesopotamian literary traditions. Her compositions were widely copied and studied in scribal schools for centuries, indicating their enduring value and canonical status. The innovative use of first-person narration and the expression of personal emotions in her poetry marked a significant development in literary style, setting a precedent for future poetic forms. Her efforts also contributed to the consolidation of religious beliefs, particularly the syncretism of Inanna and Ishtar, which shaped the broader Mesopotamian pantheon and religious practices.

8.2. Recognition in Feminism and Women's Studies

Enheduanna has received substantial attention in feminism and women's studies as a powerful symbol of early female intellectual achievement and leadership. Her rediscovery in the 20th century, particularly through the efforts of American anthropologist Marta Weigle in the 1970s, introduced her to feminist scholars as "the first known author in world literature." This led to her embrace as a "wish fulfillment figure" representing a pioneering woman. While some scholars like Eleanor Robson caution against viewing her solely as a "pioneer poetess" of feminism, emphasizing her role as her father's political and religious instrument and the most privileged woman of her time, her historical significance as a named female author continues to resonate deeply within feminist discourse.

8.3. Contributions to Rhetoric and Ancient Scholarship

Beyond her literary and religious roles, Enheduanna has been analyzed as an early theorist of rhetoric. Scholars like Roberta Binkley find evidence in The Exaltation of Inanna of classical rhetorical devices, including invention and modes of persuasion (emotional, ethical, and logical appeals), nearly 2,000 years before classical Greek rhetoric. William W. Hallo, building on Binkley's work, compared the sequence of her hymns to the biblical Book of Amos, considering them evidence of "the birth of rhetoric in Mesopotamia." Despite creating rhetorically complex compositions millennia before the ancient Greeks, Binkley argues that Enheduanna's work has been less recognized in rhetorical studies due to her gender and geographical location.

8.4. Modern Commemoration and Re-evaluation

Enheduanna's enduring legacy is reflected in modern efforts to commemorate and re-evaluate her historical importance. In 2015, the International Astronomical Union named a crater on Mercury after her, acknowledging her pioneering status. She has also been featured in popular science media, including an episode of the television series Cosmos: A Spacetime Odyssey and a Spirits Podcast episode on the goddess Inanna, further bringing her story to a wider audience. Academic initiatives and publications continue to explore her life, works, and their profound impact, ensuring her place as a pivotal figure in ancient history and literature.