1. Early Life and Accession

The early life of Emperor Duy Tân, born Nguyễn Phúc Vĩnh San, was shaped by the political turmoil of French colonial rule in Vietnam, leading to his unexpected and premature enthronement.

1.1. Birth and Family Background

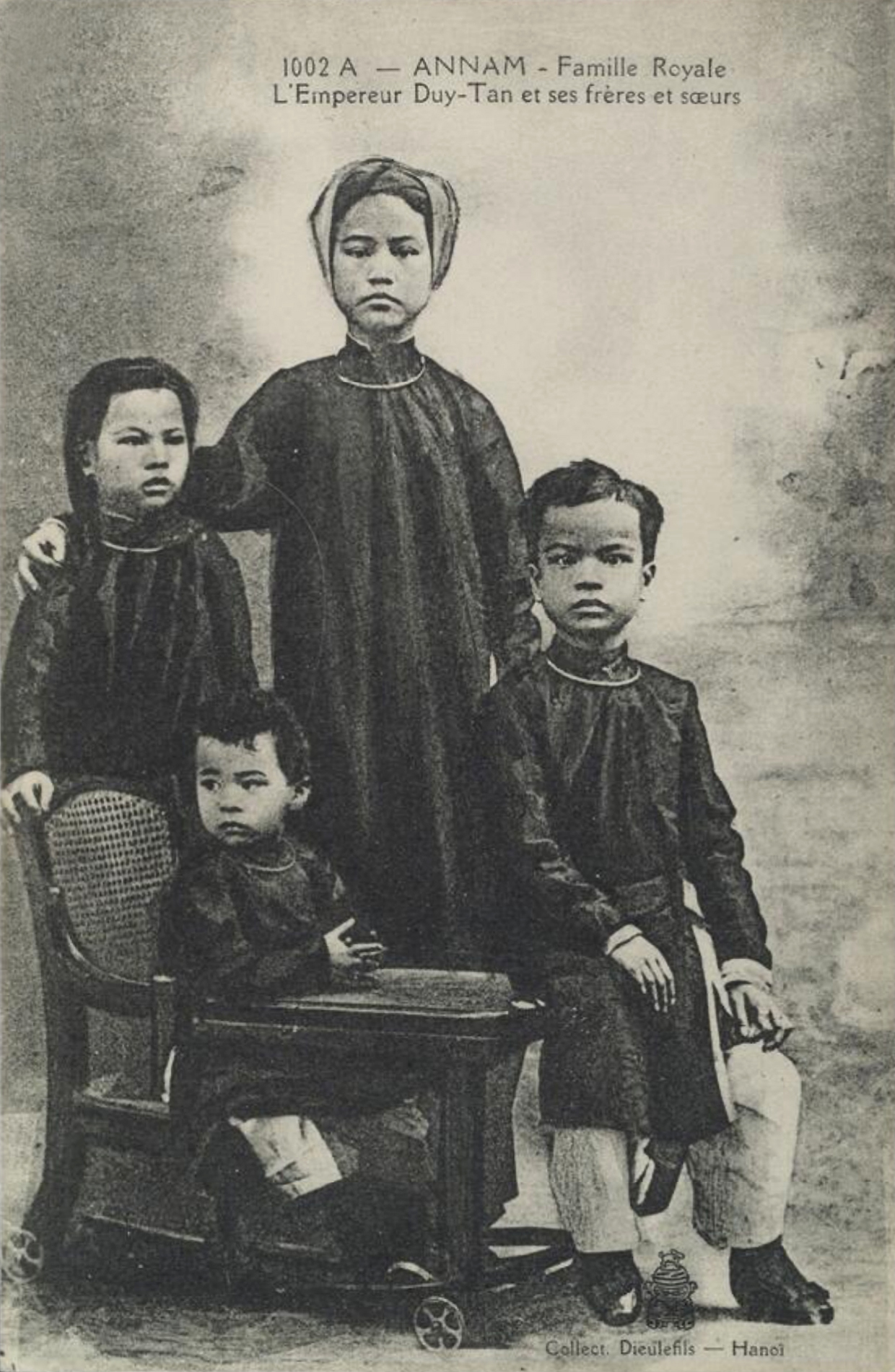

Duy Tân was born Nguyễn Phúc Vĩnh San (Nguyễn Phúc Vĩnh SanNguyễn Phúc Vĩnh SanVietnamese) on 19 September 1900, in Huế, then the imperial capital of Vietnam. Some sources, however, indicate his birth on 14 August 1899. He was the fifth son of Thành Thái Emperor, the tenth emperor of the Nguyễn dynasty, and his mother was Consort Nguyễn Thị Định (Nguyễn Thị ĐịnhVietnamese). His paternal grandfather was Dục Đức Emperor, and his grandmother was Phan Thị Châu (Phan Thị ChâuVietnamese).

1.2. Enthronement

In 1907, Duy Tân's father, Emperor Thành Thái, was declared insane by the French colonial government and subsequently exiled to Vũng Tàu. This decision was prompted by Thành Thái's overt opposition to French rule, which included appointing various officials without French permission. Some historians speculate that Thành Thái's erratic behavior was feigned to conceal his anti-French sentiments. Following Thành Thái's deposition, the French authorities sought a pliable successor. They chose the young Prince Nguyễn Phúc Vĩnh San, who was only seven or eight years old at the time, believing that his youth would make him easily influenced and molded into a pro-French ruler.

On 5 September 1907, Nguyễn Phúc Vĩnh San was enthroned with the reign name Duy Tân (Duy TânVietnamese), which means "renovation" or "friend of reform." According to an anecdote, during the selection process by French Commissioner Fernand Ernest Lévecque (Fernand Ernest LévecqueFrench), Vĩnh San was found hiding under a bed, claiming to be looking for a cricket. His disheveled appearance led the French to believe he was timid and naive, reinforcing their choice. Just one day after the coronation ceremony, French journalists reportedly noted a remarkable change in the boy's demeanor, indicating a shift from a child to a young emperor.

2. Reign and Resistance to French Rule

During his nine-year reign, Emperor Duy Tân gradually awakened to the realities of French colonial dominance and began to actively resist it, evolving from a figurehead to a determined anti-colonial leader.

2.1. Early Reign and Growing Awareness

The French colonial government's attempts to cultivate a pro-French emperor largely failed as Duy Tân matured. Despite being treated as the emperor, he observed that real authority lay with the French colonial authorities. Around 1912, at the age of 13, Duy Tân was deeply impacted by the actions of Georges Marie Joseph Mahé (Georges Marie Joseph MahéFrench), the French Resident-Superior in Central Vietnam. Mahé initiated an aggressive gold prospecting campaign, including excavating the Phước Duyên tower at Thiên Mụ Pagoda and attempting to dig up Tự Đức Emperor's tomb and the Imperial City, Huế. Duy Tân vigorously protested these acts, even ordering the palace gates closed and threatening to sever ties with the Huế authorities. Although Governor-General Albert-Pierre Sarraut (Albert-Pierre SarrautFrench) intervened to halt Mahé's actions, the incident left a lasting impression on the young emperor.

It was during this period that Duy Tân reportedly read the Treaty of 1884 (Patenôtre Treaty), realizing its unequal terms. He instructed his court, specifically Minister Nguyễn Hữu Bài (Nguyễn Hữu BàiVietnamese), who was proficient in French, to request a revision of the treaty to establish a more equitable relationship with the colonial government. However, no official dared to undertake such a sensitive task. By 1914, at 15, Duy Tân pressed his six regents to sign a document demanding a new, equal treaty from the French Resident-Superior. The regents, fearing French reprisal, refused, believing him to be mentally unstable and appealing to his mother to dissuade him. This experience fostered a strong aversion in Duy Tân not only towards the French but also towards his own court officials.

2.2. Regency System

Throughout his reign, Emperor Duy Tân did not exercise direct power, as the French colonial government imposed a regency system. Actual authority rested with a council of Vietnamese regents, who were themselves largely controlled by French Resident-Superiors and the French Prime Ministers.

The Vietnamese regents who governed under French direction included:

- Nguyễn Phúc Miên Lịch (Nguyễn Phúc Miên LịchVietnamese), as Senior Regent.

- Trương Như Cương (Trương Như CươngVietnamese), Minister of Personnel and concurrent Censorate Left Deputy Censor.

- Lê Trinh (Lê TrinhVietnamese), Minister of Rites.

- Huỳnh Côn (Huỳnh CônVietnamese), Minister of Finance and concurrent Inspectorate Governor.

- Tôn Thất Hân (Tôn Thất HânVietnamese), Minister of Justice.

- Nguyễn Hữu Bài (Nguyễn Hữu BàiVietnamese), Minister of Public Works and concurrent Minister of Military Affairs.

Meanwhile, French Prime Ministers, whose terms effectively overlapped with Duy Tân's reign, exerted significant influence as de facto regents from afar:

| Prime Minister | Term |

|---|---|

| Georges Clemenceau | 4 September 1907 - 24 July 1909 |

| Aristide Briand | 24 July 1909 - 2 March 1911 |

| Ernest Monis | 2 March 1911 - 27 June 1911 |

| Joseph Caillaux | 27 June 1911 - 13 January 1912 |

| Raymond Poincaré | 13 January 1912 - 21 January 1913 |

| Aristide Briand | 21 January 1913 - 22 March 1913 |

| Louis Barthou | 22 March 1913 - 9 December 1913 |

| Gaston Doumergue | 9 December 1913 - 9 June 1914 |

| Alexandre Ribot | 9 June 1914 - 14 June 1914 |

| René Viviani | 14 June 1914 - 29 October 1915 |

| Aristide Briand | 29 October 1915 - 17 May 1916 |

2.3. The 1916 Anti-French Uprising

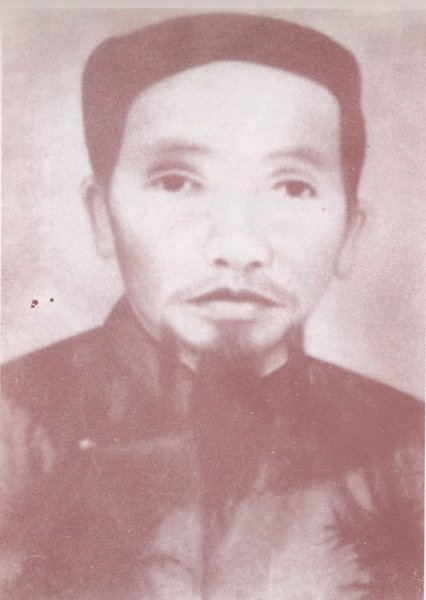

By 1916, with France deeply embroiled in World War I and Vietnamese soldiers fearing conscription for European battlefields, the time seemed ripe for an uprising. Duy Tân, already resentful of French control, secretly aligned with the Việt Nam Quang phục Hội (Vietnamese Restoration League), an anti-colonial organization founded by Phan Bội Châu in 1912.

Two key leaders of the League, Trần Cao Vân and Thái Phiên (Thái PhiênVietnamese), bribed Duy Tân's personal chauffeur, Phạm Hữu Khánh (Phạm Hữu KhánhVietnamese), a League member, to deliver secret letters to the emperor. In late April 1916, while Duy Tân was on vacation at Cửa Tùng beach, he received a letter from Trần Cao Vân and Thái Phiên. Duy Tân requested a meeting with them, which secretly took place at Hậu Hồ, where he formally agreed to support their planned rebellion.

The uprising was scheduled for 1:00 AM on 3 May. The plan called for the rebels to seize control of key roads in Huế, Quảng Nam, and Quảng Ngãi provinces, secure weapons, and facilitate Duy Tân's secret escape from the Imperial City. The signal for the full-scale rebellion was to be a cannon shot from Hải Vân Pass (Đèo Hải VânVietnamese), after which forces would proceed south to attack Quy Nhơn and Da Nang, hoping for German support. Another objective was to attack Trấn Bình Đài (Trấn Bình ĐàiVietnamese) near the Huế Imperial City and kidnap French-German residents there for their cause.

However, the plot was prematurely discovered in late April by an official in Quảng Ngãi province, who arrested and tortured a low-level League member named Võ An (Võ AnVietnamese), leading to a full confession. The French Resident-Superior in Central Vietnam, Charles (CharlesFrench), also noticed suspicious activities, such as Vietnamese soldiers' families leaving Huế. The colonial government swiftly reacted by confiscating weapons from Vietnamese soldiers and restricting their movements within barracks. Duy Tân, Trần Cao Vân, and Thái Phiên were unaware that their plan had been compromised.

Despite this, on the night of 2 May, Trần Cao Vân and Thái Phiên proceeded with the uprising. Duy Tân successfully escaped the Huế Imperial City. However, without the anticipated military support, the rebellion was quickly suppressed by the colonial authorities. Though some rebels in Tam Kỳ (Tam KỳVietnamese) managed to kill a French platoon, they were immediately subdued.

On 6 May 1916, Duy Tân, Trần Cao Vân, and Thái Phiên were captured while hiding in a temple south of the Huế Imperial City. Trần Cao Vân, Thái Phiên, Nguyễn Quang Siêu (Nguyễn Quang SiêuVietnamese), and Tôn Thất Đề (Tôn Thất ĐềVietnamese) were all summarily beheaded under the direction of Hồ Đắc Trung (Hồ Đắc TrungVietnamese).

2.4. Deposition and Exile

Following the complete failure of the 1916 uprising, the French colonial government deposed Emperor Duy Tân. Despite being captured, his young age and the French desire to avoid further unrest led to his exile rather than execution. Duy Tân defiantly refused the French offer to return to the throne as a puppet ruler, asserting his desire for true independence and freedom of action.

On 3 November 1916, Duy Tân was exiled to Réunion Island in the Indian Ocean with his father, Thành Thái Emperor. They departed from Cap Saint-Jacques (present-day Vũng Tàu) on the Guadiana ship and arrived at Pointe de Galets, Réunion Island, on 20 November at 7:30 AM.

3. Life in Exile and Independence Efforts

Emperor Duy Tân's exile on Réunion Island, far from his homeland, did not extinguish his fervent desire for Vietnamese independence. Instead, he continued his efforts, particularly through his military service during World War II.

3.1. Life on Réunion Island

Upon their arrival in Réunion, Duy Tân and his family refused the luxurious villa offered by the French, opting instead for a modest rented room in Saint-Denis. He adopted a simple lifestyle, similar to other ordinary residents, and reportedly cut ties with his father, Thành Thái, due to personality differences.

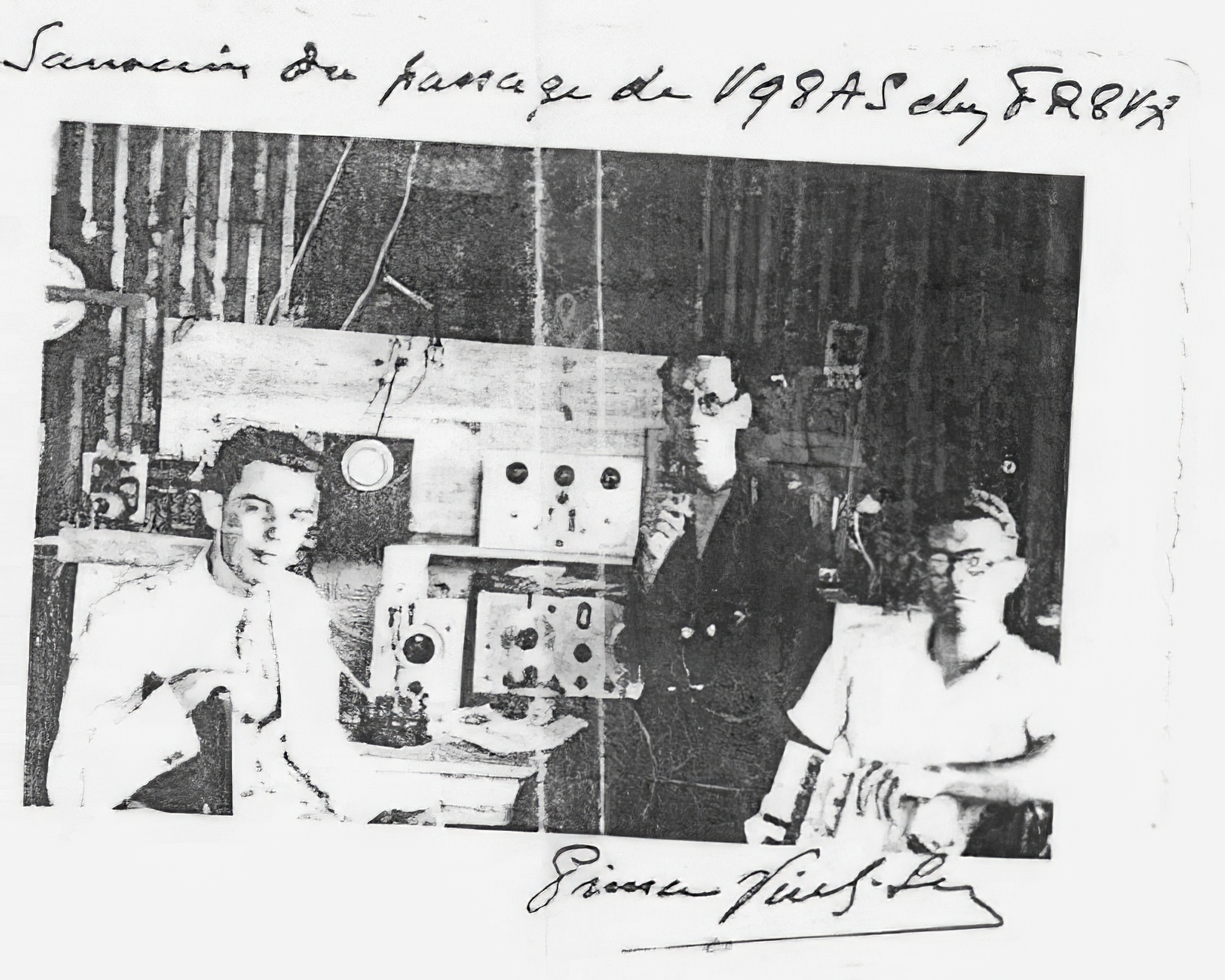

To support himself, Duy Tân trained in radio technology and opened a Radio-Laboratoire shop, specializing in sales and repairs. Concurrently, he pursued further education, studying foreign languages and law at the Leconte de Lisle High School and earning a baccalaureate degree. He largely avoided interactions with the French authorities, preferring the company of a small circle of friends. Duy Tân engaged in local cultural activities, including joining a music society, participating in horse races (where he won several competitions), and becoming a member of Freemasonry, the Franc-Macon, and a local Human Rights and Civil Liberties association.

He also contributed articles and poetry to local newspapers like Le Peuple and Le Progrès under the pseudonym Georges Dry. In 1924, his poem Variations sur une lyre briée (Variations of a Broken Lyre) won first prize in literature from the Réunion Academy of Sciences and Literature.

Despite his quiet life, Duy Tân's commitment to Vietnamese independence remained. According to E.P. Thébault, a close friend, Duy Tân only once explicitly referenced his role in the 1916 uprising in a letter to Marius Moutet (Marius MoutetFrench), the French Minister of Colonies, on 5 June 1936, seeking permission to reside in France. However, subsequent requests to join the French Army between 1936 and 1940 did not mention the rebellion. These applications were consistently rejected by the Ministry of Colonies, which noted in his personal file that he appeared "difficult to bribe, extremely independent... intriguing to leave Réunion and re-establish the throne of Annam."

3.2. World War II Service

The outbreak of World War II in 1939 profoundly impacted Duy Tân. Following the fall of Paris to Nazi Germany in 1940 and the establishment of the Vichy Regime, General Charles de Gaulle organized the Free French Forces from exile in the United Kingdom, calling for resistance against Nazi occupation. Duy Tân, viewing de Gaulle as an idol and a model for national salvation, actively responded.

He formed an organization on Réunion to resist the Vichy government's control of the island. Utilizing his radio skills, he gathered and transmitted intelligence to the Free French resistance. This activity led to his brief detention by the Vichy authorities for six weeks. After the Liberation of La Réunion by the Free French in November 1942, Duy Tân officially joined the Free French military.

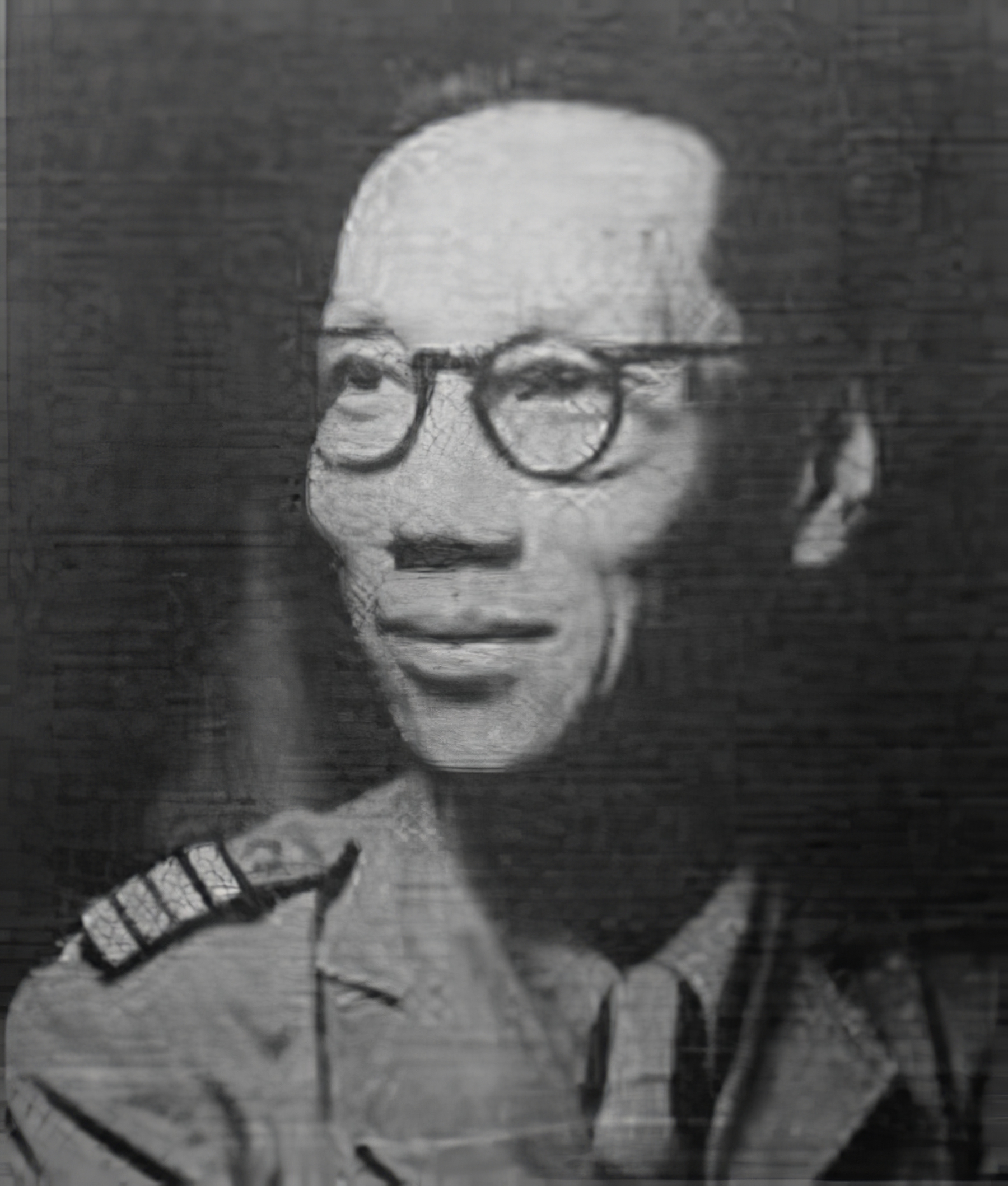

He initially served as a low-ranking naval officer on the French destroyer Léopard, working as a radio officer. In December 1942, he transferred to the Free French army as a second lieutenant. Duy Tân received successive promotions: to first lieutenant in 1943, captain in December 1944 (assigned to the 9th Colonial Infantry Division), major in July 1945, and finally lieutenant-colonel and battalion commander in September 1945. On 29 October 1945, Charles de Gaulle signed a decree formalizing Duy Tân's rapid promotions within the French Army, recognizing his wartime service.

3.3. Discussions for Return to Vietnam

As World War II drew to a close, a new political landscape emerged in Vietnam. With France facing defeat by the Viet Minh and the regime of Emperor Bảo Đại proving incapable of securing public support, French leaders sought a popular figure to stabilize the situation. General Charles de Gaulle recognized Duy Tân's enduring popularity and patriotism among the Vietnamese people.

On 14 December 1945, de Gaulle met with the former emperor, discussing the possibility of his return to Vietnam as emperor. In his War Memoirs, de Gaulle noted Duy Tân as a "resolute character" whose image remained vivid in the hearts of the Vietnamese people despite three decades of exile. Historian Philippe de Villers also observed Duy Tân's renewed prominence following Bảo Đại's abdication and his active engagement with the French government.

E.P. Thébault recounted Duy Tân's confidence after the meeting, stating that the French government had decided to restore him to the Vietnamese throne, with de Gaulle himself planning to accompany him to Vietnam in early March 1946. Preparations were underway to shape French, international, and Indochinese public opinion, and draft agreements between the two governments.

Duy Tân articulated his vision for Vietnam to Vietnamese students and expatriates in Paris, emphasizing cooperation with France. He believed that a unified, autonomous Vietnam within the French Union was achievable and that greater autonomy could be sought gradually. He argued against immediate, all-out resistance, citing his own experience and the potential for devastating war.

He expressed his personal philosophy, stating, "My love for my homeland Vietnam does not allow me to leave the door open for any internal conflict. What I desire is for all Vietnamese citizens to understand that they are one nation, and this awareness will drive them to build a Vietnam worthy of being a nation. I believe I will fulfill my duty as a Vietnamese citizen when I make the peasants of Lạng Sơn, Huế, and Cà Mau aware of their brotherhood. This unity, achieved under any regime-communist, socialist, monarchist, or royalist-is not important; what is important is to save the Vietnamese people from the disaster of division."

4. Death

Emperor Duy Tân's efforts to return to Vietnam and contribute to its future were tragically cut short by his sudden death in a plane crash.

4.1. Circumstances of Death

On 24 December 1945, Duy Tân boarded a French Lockheed C-60 military aircraft in Le Bourget, Paris, intending to return to Réunion to visit his family before embarking on his new mission in Vietnam. The plane departed from Fort Lamy (present-day N'Djamena) at 1:50 PM, heading for Bangui. On 26 December 1945, at approximately 6:30 PM GMT, the aircraft crashed near the village of Bassako, in the M'Baiki subdivision of Ubangi-Shari (present-day Central African Republic). All passengers and crew members, including a major pilot, two assistant lieutenants, two servicemen, and four civilians, perished in the accident. Duy Tân was 45 years old at the time of his death.

There were rumors, particularly among the Vietnamese population, that the Việt Minh had assassinated him, though no concrete evidence supported these claims. Some accounts suggest Duy Tân had a premonition of disaster before his departure. Initially, his remains were reportedly sent to the United States for burial.

4.2. Posthumous Honors

In recognition of his distinguished service during World War II, the French government posthumously bestowed several high honors upon Duy Tân. These included the Grand Cross of the Legion of Honour, the Médaille de la Résistance française (Resistance Medal) with a rose in March 1945, and being appointed a Companion of the Ordre de la Libération (Order of Liberation).

The Vietnamese Communist Party also held Duy Tân in high regard due to his early and consistent resistance against French colonial rule, acknowledging his patriotism.

5. Legacy and Evaluation

Emperor Duy Tân's life, though cut short, left a profound and enduring legacy in Vietnamese history, symbolizing the nation's unwavering struggle for independence. His reburial in Vietnam marked a significant moment of national reconciliation and remembrance.

5.1. Repatriation and Reburial

In 1987, Duy Tân's son, Prince Bảo Vàng (Bảo VàngVietnamese), along with other members of the former Nguyễn royal family, initiated the repatriation of his father's remains from Central Africa to Vietnam. After being recovered by Central African Republic authorities, a Buddhist funeral ceremony was held for Duy Tân's remains at the Pagode de Vincennes (International Buddhist Institute of Vincennes) in Paris on 28 March 1987. Notable attendees included then-Prime Minister Jacques Chirac, former Secretary-General for Malagasy Affairs Jacques Foccart (Jacques FoccartFrench), Marshal Jean Simon (Jean SimonFrench), President of the Free France Association, and Tran Can Khanh (Tran Can KhanhVietnamese), the Vietnamese Ambassador to France.

Subsequently, on 4 April 1987, Duy Tân's remains were transported to Vietnam and reburied with traditional rites in An Lăng, the tomb of his grandfather, Emperor Dục Đức, in Huế. In 2001, Prince Bảo Vàng further honored his father's memory by authoring a book titled Duy Tân, Empereur d'Annam 1900-1945, detailing his father's life and contributions.

5.2. Commemoration and Influence

Emperor Duy Tân is widely commemorated in Vietnam, reflecting his significant influence on the nation's independence movement. Most cities across Vietnam have named major streets in his honor.

In Ho Chi Minh City (formerly Saigon), a road previously known as Garcerie during the French colonial period was renamed Duy Tân Street (Đường Duy TânVietnamese). This street, known for its scenic tree-lined path near the Saigon University of Architecture and Law University, was even romanticized in a popular song. However, in 1985, it was renamed Phạm Ngọc Thạch Street.

In Saint-Denis, Réunion Island, a boulevard and a bridge were inaugurated in his name: Boulevard and Pont Vĩnh San, on 5 December 1992. In Vietnam, Duy Tân Street was named in the Dịch Vọng ward of Cầu Giấy district, Hanoi, in 2010. Other cities with streets named after him include Móng Cái (since 2013, extending from Hàm Nghi to Đoan Tĩnh Road), Đồng Hới, Quảng Bình (from Trần Hưng Đạo to Phạm Văn Đồng Road), and Da Nang (connecting Quân đoàn intersection to Nguyễn Văn Linh Road, passing by Military Zone 5 and Da Nang International Airport). Da Nang also hosts the Duy Tan University, a private institution.

Duy Tân's legacy is particularly notable for his unwavering dedication to Vietnamese independence from a young age, positioning him as an important figure in the anti-colonial struggle. The Vietnamese Communist Party's high regard for his resistance efforts further underscores his historical significance.

5.3. Anecdotes and Philosophy

Several anecdotes offer insights into Emperor Duy Tân's perceptive mind and his philosophical approach to Vietnam's struggle for independence.

Once, after swimming at Cửa Tùng beach, the teenage emperor's hands and feet were covered in sand. As a guard brought water for him to wash, Duy Tân reportedly asked, "When hands are dirty, we use water to wash them. But when the water is dirty, what do we use to clean it?" Before the guard could answer, he added, "Dirty water must be washed with blood, do you understand?" This exchange revealed his nascent understanding of the necessity of forceful action against oppressive forces.

On another occasion, Duy Tân was fishing at Phu Văn Lâu (Phu Văn LâuVietnamese) with Minister Nguyễn Hữu Bài. After a long wait without a bite, the young emperor posed a couplet: "Sitting on water, yet unable to stop the water; having cast the hook, one must wait for the turn." Nguyễn Hữu Bài pondered for a moment before replying: "Thinking about the world's affairs, one is disheartened by the world; thus, one closes one's eyes and lets fate take its course." Duy Tân, hearing this, reportedly criticized Nguyễn Hữu Bài for his resignation to fate, stating, "In my opinion, living like that is very sad. One must have the will to overcome hardship for life to have meaning!"

Duy Tân's philosophical outlook on national unity transcended political ideologies. He once confided, "My love for my homeland Vietnam does not allow me to leave the door open for any internal conflict. What I desire is for all Vietnamese citizens to understand that they are one nation, and this awareness will drive them to build a Vietnam worthy of being a nation. I believe I will fulfill my duty as a Vietnamese citizen when I make the peasants of Lạng Sơn, Huế, and Cà Mau aware of their brotherhood. This unity, achieved under any regime-communist, socialist, monarchist, or royalist-is not important; what is important is to save the Vietnamese people from the disaster of division." This profound statement highlights his ultimate goal of a unified, independent Vietnam, regardless of its governing structure.

6. Family

Emperor Duy Tân's family life was complex, marked by his exile and subsequent relationships with European women.

6.1. Spouses and Children

Duy Tân married Empress Mai Thị Vàng (Mai Thị VàngVietnamese) on 16 January 1916, shortly before his exile. She accompanied him to Réunion Island but returned to Vietnam two years later due to the climate, having suffered a miscarriage. Despite Duy Tân sending a divorce request and asking for the Royal Council's approval for her to remarry in 1925, Mai Thị Vàng remained loyal to him throughout her life, reportedly reciting poems that expressed her unwavering devotion.

During his exile on Réunion Island, Duy Tân entered into relationships with three other women, as Empress Mai Thị Vàng had refused to divorce him. His children from these relationships were initially given their mothers' surnames and were baptized according to Catholic rites. It is noted that these children generally did not speak Vietnamese and had limited interaction with Emperor Thành Thái. Duy Tân himself did not actively encourage his children to learn Vietnamese or about their Vietnamese heritage. In 1946, a court in Saint-Denis allowed most of Duy Tân's children to adopt his surname, Vĩnh San. Andrée Maillot and Armand Viale retained their original surnames, while Suzy, Georges, Claude, Roger, and André changed theirs to include Vĩnh San.

Here is a detailed list of his spouses and children:

- Mai Thị Vàng (Mai Thị VàngVietnamese), also known as Second Class Consort Diệu Phi (Diệu phiVietnamese): Born 1899, died 1980. She was the daughter of Mai Khắc Đôn (Mai Khắc ĐônVietnamese), Minister of Rites.

- One pregnancy, miscarriage during exile.

- Marie Anne Viale: Born 1890.

- Armand Viale: Born 1919.

- Fernande Antier: Born 1913, married 1928. They had eight children (four sons, four daughters), all bearing the surname Vĩnh San:

- Thérèse Vinh-San: Born 1928, died young.

- Rita Suzy Georgette Vinh-San: Born 6 September 1929. She began using the surname Vĩnh San in 1946.

- Solange: Born 1930, died young.

- Guy Georges Vĩnh San (Nguyễn Phúc Bảo Ngọc): Born 31 January 1933. He has four children: Patrick Vinh-San, Chantal Vinh-San, Annick Vinh-San, and Pascale Vinh-San. He and his wife, Monique, actively participate in Nguyễn dynasty ceremonies.

- Yves Claude Vĩnh San (Nguyễn Phúc Bảo Vàng): Born 8 April 1934 in Saint-Denis, Réunion. He is known for repatriating his father's remains to Vietnam in 1987. He married Jessy Tarby and had ten children (seven sons and three daughters): Yves Vinh-San, Patrick Vinh-San, Johnny Vinh-San, Jerry Vinh-San, Thierry Vinh-San, Stéphanie Vinh-San, Cyril Vinh-San, Didier Vinh-San, Marie-Claude Vinh-San, and Marilyn Vinh-San, and Doris Vinh-San. He is the current Chairman of the Đại Nam Long Tinh Viện (Đại Nam Long Tinh ViệnVietnamese), an organization focused on humanitarian, educational, and cultural activities for Vietnamese people, rather than politics.

- Joseph Roger Vĩnh San (Nguyễn Phúc Bảo Quý): Born 17 April 1938. He lives with his wife, Lebreton Marguerite, in Nha Trang, Khánh Hòa province.

- Ginette: Born 1940, died young.

- André: Died young.

- Ernestine Yvette Maillot: Born 1924.

- Andrée Maillot Vinh-San: Born 1945, died 2011. Born in Réunion.