1. Overview

Du Yuesheng (杜月笙Dù YuèshēngChinese; 1888-1951), often nicknamed "Big-Eared Du", was a powerful and influential figure in Shanghai's underworld and political landscape during the early to mid-20th century. Rising from poverty and orphanhood, he became a prominent leader of the Green Gang, establishing a vast criminal empire centered on the lucrative opium trade, gambling, and protection rackets. Beyond his illicit activities, Du strategically forged close alliances with the Kuomintang (KMT) and its leader, Chiang Kai-shek, playing a significant, albeit controversial, role in Chinese politics, including his involvement in the violent suppression of communist and labor movements during the 1927 Shanghai Massacre. He diversified his interests into legitimate businesses, such as banking and stock exchanges, intertwining his criminal wealth with the formal economy. During the Second Sino-Japanese War, he supported the Nationalist government, but his relationship with the KMT soured towards the end of the Chinese Civil War. Following the communist victory in 1949, Du fled to Hong Kong, where he lived in exile until his death in 1951. His complex legacy reflects a blend of ruthless criminality, shrewd political maneuvering, and a public image cultivated through philanthropy, leaving an indelible mark on Shanghai's socio-economic and political fabric, often at the expense of public welfare and human rights.

2. Names

Du Yuesheng's original name was 杜月生Dù YuèshēngChinese, with the final character differing from his commonly known name. Following the advice of scholar Zhang Binglin, he later changed his name to 杜鏞Dù YōngChinese. The name 月笙YuèshēngChinese, which shares the same pronunciation as his birth name but is written with a different Chinese character, became his pseudonym or courtesy name (호hoKorean). In Vietnamese, his name is also written as Đỗ Nguyệt SanhVietnamese or Đỗ Nguyệt SênhVietnamese, with "Sênh" referring to a musical instrument, and a common nickname was "Du si Telinga Besar" (Big-Eared Du). The pronunciation of "Sênh" is similar to "Thăng," which led to some Western sources mistakenly transcribing his name as "Đỗ Nguyệt Thăng." Other transliterations of his name include Dou Yu-Seng, Tu Yueh-sheng, and Du Yueh-sheng.

3. Early Life

Du Yuesheng was born on August 22, 1888, in Gaoqiao, a small town east of Shanghai, during the late Qing dynasty. His family relocated to Shanghai in 1889, a year after his birth. By the age of nine, Du had lost his immediate family: his mother died in childbirth, his sister was sold into slavery, his father passed away, and his stepmother abandoned him. Consequently, he returned to Gaoqiao to live with his grandmother. Some sources indicate he was raised by his uncle and aunt.

In 1902, Du returned to Shanghai and found work at a fruit stall in the Shanghai French Concession. However, he was later fired for theft. After a period of wandering, he became a bodyguard at a brothel, which served as a front for a common lodging house. It was during this time that he became acquainted with the Green Gang, a powerful criminal organization, and specifically with the Ba Co Bang, a sub-gang of the Green Gang. He officially joined the gang at the age of 16.

4. Entry into the Green Gang and Rise to Power

Du Yuesheng's entry into the Green Gang marked a pivotal turning point in his life. Through a friend, he was introduced to Huang Jinrong, who was then the highest-ranked Chinese detective in the French Concession Police (FCP) and one of Shanghai's most notorious gangsters. Huang's wife, Lin Guisheng, herself an influential figure in the criminal underworld, took a liking to the young Du and became his patron, assigning him to oversee security in the lodging house kitchen. Despite Huang not being a formal member of the Green Gang, Du quickly became Huang's trusted enforcer for his gambling and opium operations.

Du's prestige grew following a significant incident in 1924, when Huang Jinrong was arrested by the Shanghai Garrison police. Huang had publicly assaulted Lu Xiaojia, the son of Lu Yongxiang, the warlord then ruling Shanghai. Accounts vary, but Lu Xiaojia had either booed Huang's concubine, the opera singer Lu Lanchun, off the stage or had pursued her, despite her marriage to Huang in 1922. Huang's dozens of bodyguards, including members of the Ba Co Bang, beat Lu Xiaojia and his entourage. Du Yuesheng played a crucial role in securing Huang's release, leveraging his diplomatic skills and financial resources to pay a substantial ransom of 500.00 K USD to the warlord's father. This act solidified Du's reputation and power. Following Huang's release, Du, Huang, and Zhang Xiaolin, another prominent Green Gang member, became sworn brothers, collectively known as the "Three Tycoons of Shanghai." Although Huang was nominally the senior figure, Du's influence grew to surpass both Huang and Zhang, becoming the true "master" of Shanghai's criminal underworld.

Du's meteoric rise allowed him to acquire a four-story, Western-style mansion in the French Concession. He adopted a lavish lifestyle, exclusively wearing Chinese silks, employing White Russian bodyguards, and frequenting the city's most exclusive nightclubs and sing-song houses. He was also known for his superstitious beliefs, reportedly having three small monkey heads, specially imported from Hong Kong, sewn into his clothes at the small of his back. Du eventually took dozens of concubines, four legal wives, and six sons, reflecting his immense wealth and status.

5. Criminal Empire and Activities

By the 1930s, Du Yuesheng had consolidated his control over a vast criminal empire in Shanghai, dominating gambling dens, prostitution, and protection rackets. His most significant and profitable enterprise, however, was the opium trade. With the implicit support of the police and the colonial French government, he effectively managed the opium trade within the French Concession, becoming heavily addicted to the drug himself. He co-founded the "Sanxin Company" for opium trading with Huang Jinrong and Zhang Xiaolin.

Du's influence and wealth expanded rapidly. By 1918, just seven years after joining the underworld, he had acquired a private yacht for leisure cruises on the Yangtze River. In 1936, to further enhance his public image and obscure his humble origins, Du invested heavily in constructing a grand mansion that served as both his residence and an ancestral temple. The inauguration of this complex was a three-day spectacle, one of the most extravagant events in Shanghai, attended by hundreds of prominent figures from political and social circles, including international diplomats. The mansion featured large reception rooms, meeting halls, card rooms, and a spacious dance floor. Its side buildings were reportedly used as warehouses, one for storing opium and the other for explosives and weapons sufficient to equip an entire battalion. The opulent estate, designed with a blend of Ming dynasty palace architecture and modern Western styles, is now the Donghu Hotel in Shanghai.

Du capitalized on the colonial authorities' "New Life Movement," which ostensibly aimed to curb alcohol and opium consumption. While Shanghai police, under the nominal control of Huang Jinrong and Zhang Xiaolin, heavily penalized opium trading and use, this created a black market that Du's network exploited. He began importing heroin from Marseille, marketing it as "red opium" (hồng phiếnVietnamese). This "red opium" was actually heroin #3, around 70% pure, brownish-pink, and typically smoked or sniffed, though dangerous if injected. Du promoted it as the "world's best opium addiction cure." This "cure" was significantly cheaper (40% less than traditional opium) and offered a faster high, leading 70% of addicts to switch to Du's product. The formula for his "addiction cure" reportedly included 5 ounces of heroin, 5 ounces of caffeine, 1 ounce of quinine (an anti-malarial drug), 1 ounce of crystallized sugar, 48 ounces of milk extract sugar, and 0.5 ounces of strychnine.

Following the 1925 Geneva Convention, which outlawed heroin globally, importing the drug became more challenging. Du responded by establishing local heroin manufacturing facilities in Shanghai, sourcing raw opium from provinces like Yunnan, Guizhou, and Sichuan. Between 1925 and 1929, Du's operations imported significant quantities of chemicals for this purpose, including 1.3 t of strychnine, 24 t of caffeine, and nearly 1.5 t of heroin. The devastating consequence was that 100,000 of Shanghai's 3.5 million residents became addicted to his products. The remaining supply was sold domestically or exported to the United States, where it supplied an estimated 200,000 addicts. From 1928 to 1933, the Green Gang, under Du's direction, distilled 10.6 t of "red opium," making him the primary heroin supplier to the United States by the late 1920s.

6. Alliance with the Kuomintang and Political Activities

Du Yuesheng's strategic alliances and political maneuvering were central to his power, particularly his close ties with Chiang Kai-shek and the Kuomintang (KMT). These relationships significantly influenced Chinese politics during a turbulent era, showcasing how criminal networks could intertwine with state power.

6.1. Relationship with Chiang Kai-shek

Du Yuesheng cultivated a close relationship with Chiang Kai-shek, whose own early years in Shanghai had involved connections to the Green Gang and other secret societies. Their association reportedly began as early as 1912, shortly after Chiang's return from Japan, with Du befriending Chiang and Dai Li from his early days as a brothel/gambling bouncer. This alliance proved mutually beneficial: Chiang received crucial support from Du's underworld network, while Du gained political legitimacy and protection.

After Chiang's rise to power, Du was rewarded with the honorary title of major general and advisory positions to the military headquarters and the Executive Yuan. On October 18, 1930, the French Concession authorities also appointed Du as an advisor to the Chinese director of the Public Council, further cementing his influence within both the Chinese government and foreign concessions. Du actively assisted the Kuomintang in intelligence gathering in Shanghai, forming a close bond with Chiang's intelligence chief, Dai Li, and Yang Hu.

6.2. Role in the Shanghai Massacre (1927)

Du Yuesheng played a critical and brutal role in the Shanghai massacre, also known as the April 12 Incident, in 1927. He conspired with Chiang Kai-shek, along with his sworn brothers Huang Jinrong and Zhang Xiaolin, to form the Chinese Progress Association (中华共进会Chinese). This group, masquerading as a left-wing organization, was a paramilitary front designed to prepare for Chiang's anti-communist coup.

On the night of April 11, 1927, Du's right-hand man, Wan Molin, lured and murdered Wang Shouhua, the prominent Shanghai labor leader, at Du's residence. The following day, Du's gang members, identifiable by armbands marked "Labor" (工Chinese), launched a violent assault on the city's workers and left-wing activists. This coordinated suppression led to the widespread massacre of communists and labor union members, effectively ending the First United Front between the KMT and the Chinese Communist Party. As a reward for his contributions to the massacre, Chiang Kai-shek appointed Du Yuesheng as the head of the Shanghai Drug Control Bureau, granting him official control over the entire opium trade in China. The Green Gang also provided financial and material support to the Nationalist government, even reportedly purchasing German-made Junkers Ju 87 fighter planes under the guise of the drug control bureau. In return, Chiang granted Du the freedom to manage labor unions and various businesses without interference.

6.3. Business and Financial Ventures

Beyond his criminal enterprises, Du Yuesheng strategically diversified into legitimate financial ventures, intertwining his illicit gains with the formal economy. Starting in 1928, he founded Zhonghui Bank and subsequently became a director or supervisor at prestigious institutions such as the Bank of China and the Bank of Communications. He also held directorships at the Shanghai Cotton Exchange and the Shanghai Stock Exchange, effectively controlling significant financial flows within the French Concession.

By the 1930s, Du's influence reached its zenith. In 1931, he used his financial and political clout to open an opulent temple dedicated to his ancestors, celebrating its inauguration with a grand three-day party attended by hundreds of celebrities, politicians, businessmen, and even representatives from various foreign diplomatic missions. Chiang Kai-shek himself sent a gifted plaque for the occasion. However, within months, the private wings of this temple were clandestinely converted into a heroin manufacturing facility, becoming one of East Asia's largest drug factories.

Despite his criminal background, Du actively cultivated a public image as a philanthropist and mediator. He was involved in numerous charity projects, including hospitals, nursing homes, and orphanages, and was known for mediating labor disputes. In 1932, he established the Heng Society, a political organization that served as a front for his various activities. People from all walks of life would seek Du's intervention to resolve their problems, underscoring his immense public influence. The 1933 China Yearbook described him as "the most influential resident at the French concession in Shanghai" and an "activist for public welfare."

In August 1927, Chiang Kai-shek temporarily re-legalized the drug trade in Shanghai, placing Du Yuesheng in charge to generate funds for the military. This order was revoked in July 1928 due to strong public opposition, but during that year of relaxed control, Du Yuesheng reportedly earned a net profit of 40.00 M CNY. In 1931, Du publicly announced his departure from the gambling business and his decision to overcome his opium addiction, stating he would no longer serve as Shanghai's "heroin lord." In exchange, Chiang Kai-shek granted him control over the newly established National Lottery Company. However, this shift was often superficial. For instance, during Chiang's "New Life Movement" in 1934, which ostensibly imposed harsh penalties for opium trafficking, Du resumed large-scale opium smuggling from Sichuan to Shanghai, reportedly at Chiang's direct command. This illicit trade, operating under the guise of prohibition, generated enormous profits for both the Kuomintang and Du. Confiscated drugs were often handed over to Du for distribution rather than being destroyed. Between 1934 and 1937 alone, Du's opium and drug profits amounted to nearly 500.00 M CNY, a staggering sum compared to Shanghai's monthly medical expenses of approximately 1.50 M CNY during the same period. These vast profits enabled Du to establish and manage three banks and seventeen import-export companies, and he held chairman or leadership positions in approximately seventy other companies and factories.

6.4. Activities during the Second Sino-Japanese War

Following the Mukden Incident in 1931, Du Yuesheng became active in wartime services, organizing donation drives, boycotts of Japanese goods, and funding academic and artistic activities, demonstrating a public stance against Japanese aggression. When the Second Sino-Japanese War officially erupted in 1937 with the Second Battle of Shanghai, Du was reportedly asked to sink his ships at the mouth of the Yangtze River to block Japanese forces. However, unlike his sworn brother Zhang Xiaolin, Du refused to collaborate with the Japanese occupation forces. He initially fled to British Hong Kong in late 1938, leaving his business affairs to his eldest son. Du viewed Hong Kong as a safe haven unaffected by the war and began rebuilding a new Green Gang empire there, holding a ceremony in mid-1939 to establish himself as the first "Wu" generation boss. He built Green Gang influence in Hong Kong for nearly eight years.

During the war, Du's Green Gang operatives, working in conjunction with Dai Li, Chiang's intelligence chief, continued to smuggle weapons and essential goods to the Nationalist forces, providing crucial logistical support. Du also served as a board member of the Red Cross Society of the Republic of China and established several companies and factories in the "free area" of China, demonstrating his commitment to the Nationalist cause. In Chongqing, he also became known as a "generous philanthropist," leading several KMT-established charities and relief organizations aimed at garnering public support. After the Japanese occupation of Hong Kong in December 1941, following the outbreak of the Pacific War, Du relocated to Chongqing, the wartime capital of the Nationalist government. There, he continued to profit significantly by facilitating the flow of goods between KMT-controlled territories and Japanese-occupied areas. He also helped organize and technically support the KMT's drug trade, which became a vital source of funding for Chiang's government. This involved collecting raw opium from remote areas in western and southern China, which was then processed into heroin by skilled chemists, primarily of Teochew origin, and subsequently smuggled to Shanghai, Hong Kong, and the United States.

After Japan's surrender in September 1945, Du Yuesheng returned to Shanghai, expecting a hero's welcome. However, he was reportedly shocked to find that many citizens did not welcome him, believing he had abandoned them to the Japanese occupation. Following the war, the relationship between Du and Chiang Kai-shek began to sour due to widespread corruption and criminal activities within the Kuomintang. In 1948, Chiang's son, Chiang Ching-kuo, launched an anti-corruption campaign in Shanghai. Du's son, Du Weiping, was targeted and initially sentenced to six months in prison. Chiang Ching-kuo also investigated the funds of Du's various charities, including the Relief Society, Red Cross, Shanghai Workers' Mutual Aid Association, and National Lottery. Du Yuesheng reportedly threatened to expose embezzlement crimes committed by Chiang Ching-kuo's relatives to secure his son's release. Although he managed to get his relatives freed, his own son was eventually imprisoned, marking the definitive end of the alliance between Du and the Chiang family. Despite this, Du was elected as a representative to the People's Congress of the Nationalist Government in 1948. He also served as president or director of over 70 commercial organizations and held leadership roles in more than 200 enterprises and institutions, reflecting his continued, albeit waning, influence.

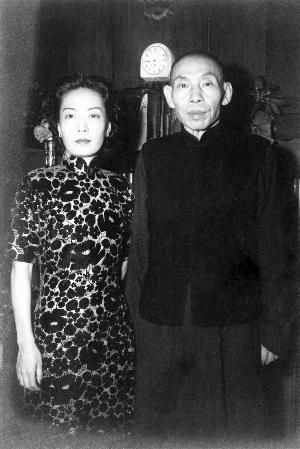

7. Personal Life

Du Yuesheng had a complex personal life with five wives throughout his lifetime: Shen Yueying, Chen Yuying, Sun Peihao, Yao Yulan, and the renowned Peking opera performer Meng Xiaodong, whom he married in 1950 and divorced in 1951. He fathered eight sons and three daughters. His sons were Du Weiping, Du Weishan, Du Weixi, Du Weihan, Du Weiwei, Du Weining, Du Weixin, and Du Weiwei. His daughters were Du Meiru, Du Meixia, and Du Meijuan.

His seventh son, Du Weishan, gained recognition for serving as one of the first secret intermediaries between Taipei and Beijing in the early 1980s, during a period when official communication channels between the two administrations were non-existent. Du Weishan was also a noted numismatist who resided in Vancouver, Canada, and passed away in March 2020. Later in his life, he made significant donations of ancient coins to the Shanghai Museum.

Du Meiru, his eldest daughter, settled with her husband in Jordan in the 1960s, where she operated a restaurant. She also appeared as herself in the 2010 film I Wish I Knew by director Jia Zhangke.

8. Exile and Death

8.1. Exile in Hong Kong

In April 1949, on the eve of the fall of Shanghai to the Chinese Communist Party during the Chinese Civil War, Du Yuesheng decided to move to British Hong Kong. This decision came despite overtures from both the retreating Kuomintang and the victorious Communists, indicating his loss of influence and a desire to avoid the political upheaval on the mainland. He lost all his power and networks in Shanghai, as the Green Gang, having aided Chiang, lost ground when the Kuomintang's territory gradually shrank.

During his exile in Hong Kong, Du faced various challenges. While some accounts suggest he lived in relative poverty in slums, others indicate he managed to retain a considerable private fund. His health deteriorated rapidly during this period, exacerbated by long-term opium addiction and severe asthma. He also began to lose his eyesight and showed signs of aging.

8.2. Death and Burial

Du Yuesheng died in Hong Kong on August 16, 1951, primarily due to complications arising from his prolonged opium addiction. Despite his deteriorating health, he had reportedly considered returning to mainland China shortly before his death.

It is widely believed that his body was transported by one of his wives to Taiwan and subsequently buried in Xizhi District, New Taipei. However, some skeptics question whether his tomb in Xizhi actually contains his remains. Following his interment, the Taiwanese authorities erected a statue of Du in Xizhi. The four-character inscription on the statue praises Du's "loyalty" and "personal integrity," a testament to his complex and often contradictory legacy.

9. Assessment and Legacy

Du Yuesheng's overall impact on Shanghai and China is complex and multifaceted, marked by a blend of ruthless criminal enterprise, shrewd political maneuvering, and a cultivated public image. His legacy remains a subject of critical examination, especially concerning its social, economic, and political dimensions, with an emphasis on the detrimental effects of his criminal empire on vulnerable populations and social justice.

9.1. Social Impact and Criticisms

Du Yuesheng's criminal activities had profound and often devastating social consequences for Shanghai society. His dominance in the opium and heroin trade led to widespread addiction, with an estimated 100,000 people in Shanghai becoming addicts to his products, and his network supplying hundreds of thousands more globally. This exploitation of public health for immense profit stands as a significant criticism of his career.

His involvement in the 1927 Shanghai Massacre, where his gang members brutally suppressed communist and labor movements, resulted in the deaths of numerous workers and activists. This act solidified his reputation as a ruthless enforcer for the Kuomintang, directly contributing to human rights abuses and the suppression of labor rights in Shanghai. Despite his public philanthropy, which included supporting hospitals, nursing homes, and orphanages, these charitable endeavors were often funded by his illicit gains and served to legitimize his image, distracting from the corruption, violence, and exploitation inherent in his criminal empire. His return to Shanghai after World War II was met with a cold reception, as many citizens felt he had abandoned them during the Japanese occupation. His later conflicts with Chiang Ching-kuo's anti-corruption campaign further exposed the deep-seated corruption within the KMT's alliance with the underworld.

9.2. Historical Re-evaluation

Historically, Du Yuesheng has been re-evaluated as a figure who navigated the tumultuous period of early 20th-century China with exceptional cunning and adaptability. While his criminal activities and the violence he employed are undeniable, his ability to transition from a street thug to a financial tycoon and a political power broker is often highlighted. He was described in the 1933 China Yearbook as "the most influential resident at the French concession in Shanghai" and an "activist for public welfare," reflecting the public perception he meticulously crafted. He was known for his mediation skills in labor disputes and for upholding a certain code of conduct within the underworld, often showing respect to his seniors like Huang Jinrong. Despite his criminal background, he was also reportedly a devout Confucian conservative.

However, contemporary perspectives critically balance these aspects against the immense social harm caused by his drug empire and his role in political violence. His actions, particularly the widespread addiction to his heroin products and his part in the Shanghai Massacre, underscore the destructive impact of his career on Chinese society. For many years, official studies and biographies of Du Yuesheng were banned in China, as they were perceived to encourage criminal behavior. However, in recent times, research into his life has become more prevalent, allowing for a more nuanced understanding of his complex place in modern Chinese history.

9.3. Portrayals in Popular Culture

Du Yuesheng's life has captivated public imagination and has been depicted in various forms of popular culture, reflecting his enduring, albeit controversial, influence.

- The novel White Shanghai by Elvira Baryakina (2010) recounts Du's rise to power.

- The short story "Mother Tongue" by Amy Tan mentions Du's early days and a purported visit to Tan's mother's wedding.

- Lord of the East China Sea (上海皇帝之歲月風雲Chinese) and Lord of the East China Sea II (上海皇帝之雄霸天下Chinese), a two-part Hong Kong film from 1993, are based on Du's life. Ray Lui plays the lead character, Lu Yunsheng (陸雲生Chinese).

- The Founding of a Republic (建国大业Chinese), a 2009 historical film commissioned by the Chinese government, features Feng Xiaogang in a cameo role as Du.

- The Last Tycoon (大上海Chinese), a 2012 Hong Kong film, features the main character Cheng Daqi (成大器Chinese), portrayed by Chow Yun-fat and Huang Xiaoming at different life stages, and is loosely based on Du.

- In the 2015 Hong Kong TVB drama Lord of Shanghai, the main character Kiu Ngo Tin, portrayed by Anthony Wong and a younger version by Kenneth Ma, is based on Du Yuesheng.

- The cancelled video game Whore of the Orient was planned to be set in 1936 Shanghai during Du's era.

- Fictionalized characters inspired by Du and events from his life have appeared in films such as Ba bai zhuang shi (1976), Da Shang Hai 1937 (1986), Luo man di ke xiao wang shi (2016), and Jian jun da ye (2017).

- In Japan, Lucien Bodard's 1983 novel The Consul significantly influenced the popular image of Du Yuesheng. He has also been featured in Japanese works such as Shen Ji's Shanghai no Kaoyakutachi (The Bosses of Shanghai), Lynn Pan's Old Shanghai: Emperor of the Underworld, Xi Erxiao's China Mafia Den: The Man Called Godfather of Shanghai, and the manga Tokyo Bomb by Masao Yajima and Jun Hayase. The 2020 manga Manchuria Opium Squad also features Du Yuesheng as the father of the heroine.