1. Overview

David Sharp was a British mountaineer whose death on Mount Everest in 2006 sparked a significant ethical debate within the global climbing community. Sharp, known for his independent climbing philosophy and preference against the use of supplementary oxygen, was found in critical condition near the summit by multiple climbing teams who passed him without providing substantial aid. His demise ignited discussions about the responsibility of climbers to assist those in distress at high altitudes, contrasting the pursuit of the summit with humanitarian obligations. The incident drew widespread criticism from prominent figures like Sir Edmund Hillary and led to a re-examination of ethical standards in high-altitude mountaineering, while also highlighting the inherent risks and personal accountability embraced by climbers in such extreme environments.

2. Life and Background

David Sharp's life was marked by a strong academic foundation and a deep passion for mountaineering, which he pursued with a distinct philosophy of self-reliance.

2.1. Early Life and Education

David Sharp was born on February 15, 1972, in Harpenden, near London, England. He attended Prior Pursglove College and later pursued higher education at the University of Nottingham, from which he graduated in 1993 with a degree in Mechanical Engineering. His interest in climbing began during his middle school years, starting with ascents of local peaks such as Roseberry Topping. During his university years, he was an active member of the Mountaineering Club, further developing his skills and passion for the sport.

2.2. Career and Climbing Preparation

After completing his education, Sharp initially embarked on a professional career, working for QinetiQ, a global security company. He took a six-month sabbatical from this job to embark on extensive backpacking trips through South America and Asia, further broadening his experience with adventurous travel. In 2005, he left his position at QinetiQ and undertook a teacher training course, with plans to begin work as a math teacher in the autumn of 2006. This career transition reflected his evolving priorities, as he sought to dedicate more time to his mountaineering pursuits while maintaining a professional life.

3. Climbing Career

David Sharp's climbing career was characterized by a distinctive approach to mountaineering, emphasizing independence and self-sufficiency, which he applied across several significant expeditions before his final ascent of Mount Everest.

3.1. Climbing Philosophy and Approach

Sharp held a unique and rigorous philosophy regarding mountaineering, particularly his approach to high-altitude climbs. He strongly believed in independent climbing, preferring to undertake expeditions without the assistance of professional guides or local support, such as Sherpas, especially on mountains he was familiar with. Furthermore, Sharp was known for his aversion to artificial enhancements, including high-altitude drugs or supplementary oxygen. He did not consider climbing Mount Everest with supplementary oxygen to be a genuine challenge, viewing it as a compromise to the true spirit of mountaineering. This commitment to self-reliance meant he often declined offers for more structured expeditions, opting instead to climb at his own pace and according to his own stringent standards, even if it meant facing greater risks.

3.2. Major Expeditions

Sharp's mountaineering achievements spanned several notable peaks across different continents. Beyond his early climbs like Roseberry Topping, he successfully summited Matterhorn, Mount Elbrus, Mount Kilimanjaro, and Gasherbrum.

- 2001 Gasherbrum II expedition: In 2001, Sharp participated in an expedition to Gasherbrum II, an 26 K ft (8.04 K m) mountain located in the Karakoram range, on the border between Gilgit-Baltistan province, Pakistan-administered Kashmir, and Xinjiang, China. This expedition, led by Henry Todd, did not reach the summit due to adverse weather conditions.

- 2002 Cho Oyu expedition: In 2002, Sharp joined an expedition to Cho Oyu, an 27 K ft (8.20 K m) peak in the Himalayas, as part of a group led by Richard Dougan and Jamie McGuinness of the Himalayan Project. The team successfully reached the summit. However, the expedition was marred by tragedy when one member died after falling into a crevasse. Richard Dougan regarded Sharp as a strong climber but noted his tall and skinny physique, possessing little body fat, which can be critical for survival in extreme cold-weather mountaineering.

- 2003 Mount Everest expedition: Sharp's first attempt on Mount Everest was in 2003 with a group led by British climber Richard Dougan, which included Terence Bannon, Martin Duggan, Stephen Synnott, and Jamie McGuinness. While only Bannon and McGuinness reached the summit, the group incurred no fatalities. Dougan observed that Sharp acclimatized well and was considered the strongest member of their team. Sharp was also noted for his pleasant demeanor at camp and his talent for rock climbing. However, Sharp began to experience frostbite during the ascent, leading most of the team to turn back with him from the summit. During this climb, Sharp and Dougan assisted a struggling Spanish climber by providing extra oxygen. Sharp ultimately lost some of his toes due to frostbite on this expedition.

- 2004 Mount Everest expedition: In 2004, Sharp joined a Franco-Austrian expedition to the north side of Mount Everest. He managed to climb to an altitude of 28 K ft (8.50 K m) but did not reach the summit, stopping before the First Step as he could not keep pace with the rest of the team. The expedition's leader was Hugues d'Aubarede, a French climber who later died in the 2008 K2 disaster. D'Aubarede's group summited on the morning of May 17, becoming the 56th French person to summit Everest, and included Austrians Marcus Noichl, Paul Koller, and Fredrichs "Fritz" Klausner, as well as Nepalis Chhang Dawa Sherpa, Lhakpa Gyalzen Sherpa, and Zimba Zangbu Sherpa (also known as Ang Babu). D'Aubarede and Sharp held differing views on the use of supplementary oxygen during climbing, with D'Aubarede asserting that it was wrong to climb alone and attempt a summit without it. Sharp's emails to other climbers confirmed his disbelief in using extra oxygen. Although Sharp joined four climbers on this expedition and temporarily relented on his stance by using oxygen, he incurred frostbite on his fingers during this ascent. He would later return in 2006 for his solo attempt, adhering to his independent philosophy.

4. 2006 Mount Everest Expedition and Death

David Sharp's final expedition to Mount Everest in 2006 culminated in his death, which became a focal point for intense ethical debates within the mountaineering community.

4.1. Expedition Preparation and Plans

For his 2006 Everest climb, Sharp returned with the explicit intention of reaching the summit on a solo ascent, arranged through Asian Trekking. He planned to achieve this without the use of supplementary oxygen, a decision considered extremely risky even for highly acclimatized and strong climbers like Sherpas. Sharp, however, did not view climbing Everest with supplementary oxygen as a true challenge.

Sharp opted for a "basic services" package from Asian Trekking, which cost around 6.20 K USD. This package provided a permit, transportation into Tibet, oxygen equipment, food, and tents up to the Mount Everest "Advance Base Camp" (ABC) at an elevation of about 21 K ft (6.34 K m). Crucially, this package did not include support beyond a certain altitude on the mountain, nor did it provide a Sherpa climbing partner, though this option was available for an additional fee. Sharp was grouped with 13 other independent climbers, including Vitor Negrete, Thomas Weber, and Igor Plyushkin, who also died attempting to summit that year as part of the International Everest Expedition. This group was not a cohesive expedition with a designated leader, though it is considered good climbing etiquette for members to generally keep track of one another.

Sharp's friend, Jamie McGuinness, an experienced climber and guide, had invited Sharp to join his organized expedition at a discount before Sharp booked his trip with Asian Trekking. Sharp acknowledged it as a good deal but declined, preferring to act independently and climb at his own pace. He chose to climb alone without a Sherpa, decided not to bring sufficient supplementary oxygen (reportedly only two bottles, enough for approximately 8 to 10 hours of high-altitude climbing), and did not carry a radio or satellite phone to call for help in case of problems.

4.2. Climb and Distress

Sharp was transported by vehicle to the Base Camp, with his equipment moved by yak train to the Advance Base Camp as part of his Asian Trekking package. He remained at ABC for five days to acclimatize to the altitude, making several trips up and down the mountain to establish and stock his upper camps and further acclimatize.

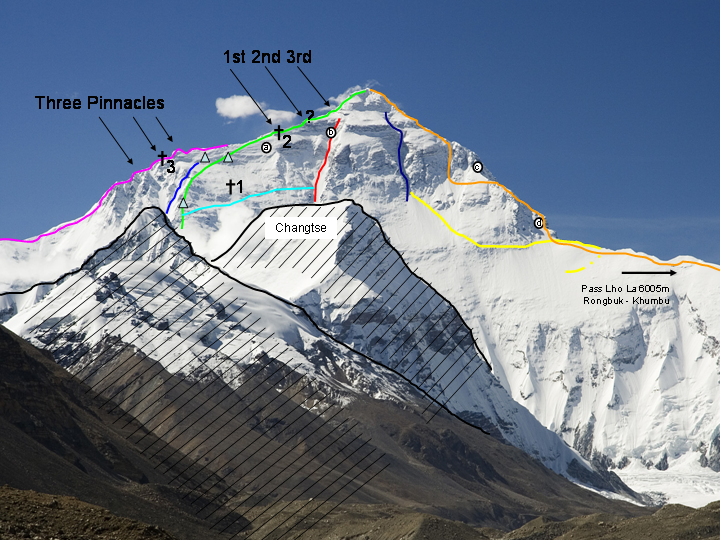

Sharp likely began his summit attempt from a high camp below the Northeast Ridge during the late evening of May 13. His route involved climbing the "Exit Cracks," traversing the Northeast Ridge, including the Three Steps, reaching the summit, and then descending back to his high camp. He reportedly carried a limited supply of supplementary oxygen, intending to use it only in an emergency.

Sharp either managed to reach the summit or turned back near it, beginning his descent very late on May 14. During his nighttime descent, he was forced to bivouac at approximately 28 K ft (8.50 K m) under a rocky overhang known as Green Boots' Cave, located near the so-called First Step. He had no remaining supplementary oxygen, likely due to a combination of bad weather conditions, possible equipment problems, and a degree of altitude sickness resulting from oxygen deprivation. This night was one of the coldest of the season.

Sharp's predicament was not immediately known because he was not climbing with an expedition that would monitor climbers' locations. He had not informed anyone beforehand of his summit attempt, although other climbers did spot him during his ascent. Furthermore, he lacked a radio or satellite phone to notify others, and two other less experienced climbers from his group, including Malaysian Ravi Chandran (also known as Ravichandran Tharumalingam), went missing around the same time. Chandran was eventually found but required medical attention for frostbite.

Members of Sharp's climbing group, including George Dijmarescu, realized Sharp was missing when he did not return by the evening of May 15 and no one reported seeing him. Initially, there was no immediate concern, as Sharp was an experienced climber known for turning back when encountering problems; it was surmised that he had sought shelter at one of the higher camps or bivouacked somewhere higher on Everest. While high-altitude bivouacs are extremely risky, they are sometimes recommended in certain extreme situations.

Sharp ultimately died under the rocky overhang in Green Boots' Cave, sitting with his arms clasped around his legs, next to the body of Green Boots. The "cave" is situated approximately 820 ft (250 m) above the high camps, commonly referred to as Camp 4. However, the extreme cold, fatigue, lack of oxygen, and darkness made a descent to Camp 4 extremely dangerous or nearly impossible.

4.3. Encounters with Other Climbers and Lack of Rescue

David Sharp's final hours involved multiple encounters with other climbing teams, none of whom were able to provide the necessary aid for his rescue.

- Himex expedition - first team: Himex organized several teams for the 2006 climbing season. The first team, guided by Bill Crouse, passed Sharp at around 01:00 on May 14 during their ascent near the North route's "Exit Cracks." When Crouse's team descended around 11:00, Sharp was seen again, higher up on the mountain at the base of the Third Step. After Crouse's expedition had descended to the Second Step, more than an hour later, Sharp was observed above the Third Step but climbing very slowly, having moved only about 295 ft (90 m).

- Turkish team: A team of Turkish climbers also reported encountering Sharp. They departed their high camp in the evening on May 14, traveling in three separate groups. The first group encountered Sharp around midnight during their ascent. They noticed he was alive and initially believed he was a climber taking a short break; Sharp reportedly waved them on. Other Turkish climbers who later noticed Sharp thought he was already deceased, as the recovery of a dead climber's body is almost impossible at such high altitudes. It is believed that Sharp might have fallen asleep between these two encounters. Sharp's desire to sleep was noted by other climbers in later encounters, with news stories reporting a quote attributed to him saying he wanted to sleep. Some members of the Turkish team summited early on May 15, while others turned back near the summit due to medical difficulties within their group. The Turkish team members who turned back re-encountered Sharp at about 07:00. One of them, Turkish team leader Serhan Pocan, had initially thought Sharp was a recently deceased climber during his previous passing. In the daylight, Pocan realized that Sharp was alive but in critical condition. Sharp had no oxygen left, suffering from severe frostbite and some frozen limbs. Two Turkish climbers stayed with him, gave him something to drink, and attempted to help him move. However, they were forced to leave due to their own dwindling oxygen supplies and the need to safely descend Burçak Özoğlu Poçan, a climber in their group experiencing medical issues. Serhan Pocan radioed the part of his team descending from the summit about Sharp's condition and continued his descent with Burçak. Around 08:30, two other members of the Turkish team cleaned out Sharp's iced mask to provide oxygen, but they too had to descend when they began to run out. Later, the remaining Turks and some Himex expedition members attempted to further assist Sharp.

- Himex expedition - second team: The second Himex team included Maxime Chaya, New Zealand double-amputee Mark Inglis, Wayne Alexander (who designed Inglis' prosthetic climbing legs), Discovery cameraman Mark Whetu, experienced climbing guide Mark Woodward, and their Sherpa support team, including Phurba Tashi. The team left their high camp, located at around 27 K ft (8.20 K m), near midnight on May 14. Chaya and the Sherpa porter/guide, Dorjee, were ahead by about half an hour. At approximately 01:00, Woodward and his group (including Inglis, Alexander, Whetu, and some Sherpa porters) encountered an unconscious Sharp. He was afflicted with severe frostbite but was noticeably breathing. Woodward observed that Sharp was wearing thin gloves and had no oxygen. They yelled at Sharp to get up, get moving, and follow their headlamps back to the high camps. Woodward shined his headlamp in Sharp's eyes, but Sharp remained unresponsive. Woodward, believing Sharp was in a hypothermic coma, commented, "Oh, this poor guy, he's stuffed," and concluded that Sharp could not be rescued. Woodward attempted to radio their Advanced Base Camp about Sharp but received no reply. Alexander commented, "God bless... Rest in peace," before the group moved on. Woodward later stated that it was not an easy decision, but his chief responsibility was the safety of his team members. Stopping in the extreme cold at that altitude would have compromised his team's survival. At their elevation, a person must be conscious and able to walk to be considered "rescuable."

Maxime Chaya reached the summit at around 06:00. During his descent, Chaya and his Sherpa porter/guide, Dorjee, encountered Sharp a little after 09:00 and attempted to help him. Chaya also notified the Himex expedition manager Russell Brice via their radio. Chaya had not seen Sharp in the dark during his ascent. He observed that Sharp was unconscious, shivering severely, and was wearing only a thin pair of wool gloves with no hat, glasses, or goggles. Sharp was severely frostbitten, with frozen hands and legs, and was found with only one empty oxygen bottle. At one point, Sharp stopped shivering, leading Chaya to believe he had died; sometime later, he started shivering again. They attempted to give him oxygen, but there was no response. After about an hour, Brice advised Chaya to return, stating that there was nothing more to be done and that Chaya was running out of oxygen. Chaya later told The Washington Post: "It almost looks like he [David Sharp] had a death wish."

Soon after Chaya descended, some of the other members from the second Himex group and a Turkish group re-encountered Sharp during their descent and attempted to help him. Phurba Tashi, the lead Sherpa guide for Himex, and a Turkish Sherpa guide gave Sharp oxygen from a spare bottle they found, patted him in an attempt to aid circulation, and tried to give him something to drink. At one point, Sharp mumbled a few sentences. The group attempted to get Sharp to his feet, but he could not stand, even with assistance. Moving Sharp into sunlight required the two strongest Sherpa climbers and took 20 minutes. Deciding that Sharp could not be rescued, the group descended.

4.4. Controversy with Mark Inglis

Following David Sharp's death, Mark Inglis was initially severely criticized by the media and others, including Sir Edmund Hillary, for not helping Sharp. Inglis stated that Sharp had been passed by 30 to 40 other climbers heading for the summit who did not attempt a rescue, but he was particularly criticized because of his higher public profile. Inglis maintained that he believed Sharp was ill-prepared, lacking proper gloves and sufficient supplementary oxygen, and was already doomed by the time of his ascent. He initially stated, "I... radioed, and [expedition manager Russell Brice] said, 'Mate, you can't do anything. He's been there X number of hours without oxygen. He's effectively dead.' Trouble is, at 28 K ft (8.50 K m) it's extremely difficult to keep yourself alive, let alone keep anyone else alive."

Statements by Inglis suggested that he believed Sharp was beyond help by the time the Inglis party passed him during their ascent and that he had made radio calls to their base camp. However, Russell Brice, who was initially criticized for reportedly advising Inglis to move on without assessing the situation, denied receiving any radio call about Sharp until he was notified some eight hours later by climber Maxime Chaya. At this time, Sharp was unconscious, shivering violently, had severe frostbite, and was without gloves or oxygen. It was later revealed that Brice kept detailed logs of radio calls with his expedition members, recording all radio traffic, and that the Discovery Channel was filming Brice during this time. All these records confirmed that Brice was first notified of Sharp being in trouble when climber Chaya contacted him at about 09:00.

In the documentary Dying for Everest, Mark Inglis stated: "From my memory, I used the radio. I got a reply to move on and there is nothing that I can do to help. Now I'm not sure whether it was from Russell [Brice] or from someone else, or whether you know... it's just hypoxia and it's ... it's in your mind." It is believed that if Inglis did have a radio conversation where he was told that "he's been there X number of hours without oxygen," it must have been on Inglis's descent, as during his ascent there was no way for Brice or other climbers to have known how long Sharp had been there. In July 2006, Inglis retracted his claim, blaming the extreme conditions at altitude for the uncertainty in his memory.

The Discovery Channel was filming the Himex expedition for a documentary, Everest: Beyond the Limit, including an HD camera carried by Whetu (which became unusable during the ascent due to the extreme cold) and helmet cameras for some of the Himex Sherpas. The footage indicated that Sharp was only found by Inglis's group on their descent. However, the climbers with Inglis confirmed that Sharp was discovered on the ascent, but not that Brice was contacted regarding Sharp at this time. By the time the Inglis group reached him on the descent and contacted Brice, they were low on oxygen and heavily fatigued, with several cases of severe frostbite and other issues, making any rescue by them impossible.

4.5. Testimony of Jamie McGuinness

New Zealand mountaineer Jamie McGuinness, who had previously climbed with Sharp, provided further insight into the situation. He reported that a Sherpa named Dawa from Arun Treks reached Sharp on the descent. McGuinness recounted, "...Dawa from Arun Treks also gave oxygen to David and tried to help him move, repeatedly, for perhaps an hour. But he could not get David to stand alone or even stand resting on his shoulders. Dawa had to leave him too. Even with two Sherpas, it was not going to be possible to get David down the tricky sections below."

McGuinness was part of an expedition that successfully climbed Cho Oyu with Sharp in 2002 and was also on the 2003 expedition to Mount Everest with Sharp and other climbers. In 2006, he offered Sharp the opportunity to climb Everest with his organized expedition for little more than what Sharp paid Asian Trekking. In the documentary Dying For Everest, McGuinness noted that Sharp did not expect to be rescued, stating, "absolutely not, he was clear to me that he understood the risks and he did not want to endanger anyone else."

4.6. Documentary and Media Coverage

David Sharp's death and the ensuing controversy were extensively covered in television documentaries, significantly shaping public perception and discourse. Sharp was briefly caught on camera on the morning of May 15 while filming the first season of the television show Everest: Beyond the Limit, which was filmed during the same climbing season as his ill-fated expedition. The footage was captured from the helmet camera of a Himex Sherpa during their descent, who was attempting to help Sharp along with a Turkish Sherpa and one of the other groups of Himex climbers, including Mark Inglis.

Additionally, Sharp's story was a central focus of the 2007 documentary Dying for Everest, produced by New Zealand TV3 and later aired on Sky in April 2009. This documentary, along with other media coverage, highlighted the ethical dilemmas faced by climbers and the perceived lack of assistance given to Sharp. Media narratives often criticized the base camp for allegedly ignoring alerts and various climbing teams for prioritizing their summit attempts over aiding Sharp. Some reports, including those from Mark Inglis in Dying for Everest, suggested that many climbers might have confused Sharp with the deceased climber known as Green Boots, leading them to pass by without offering help. Conversely, some media also presented arguments that Sharp himself bore responsibility due to his decision to climb solo with limited resources and without a radio.

5. Reactions and Ethical Debate

David Sharp's death on Mount Everest provoked strong reactions from prominent figures and sparked a wide-ranging ethical debate within the mountaineering community regarding responsibility, aid, and the culture of high-altitude climbing.

5.1. Criticism from Sir Edmund Hillary

Sir Edmund Hillary, the first person to reach the summit of Mount Everest, was highly critical of the reported decision by climbers to not attempt to rescue Sharp. He publicly condemned the actions, stating that leaving other climbers to die is unacceptable and that the desire to reach the summit had become paramount. Hillary expressed his horror at what he perceived as a "callous attitude" among modern climbers. He told The New Zealand Herald: "I think the whole attitude towards climbing Mount Everest has become rather horrifying. The people just want to get to the top. It was wrong if there was a man suffering altitude problems and was huddled under a rock, just to lift your hat, say good morning and pass on by." He added, "They don't give a damn for anybody else who may be in distress and it doesn't impress me at all that they leave someone lying under a rock to die," concluding that their priority was to reach the top, and the welfare of a member of another expedition was "very secondary." Hillary also specifically called Mark Inglis "crazy" for his actions and statements.

5.2. Sharp's Mother's Stance

In contrast to the widespread criticism, David Sharp's mother, Linda Sharp, did not blame other climbers for her son's death. She conveyed her perspective to The Sunday Times, stating, "Your responsibility is to save yourself - not to try to save anybody else." She further elaborated that David was found under a rock, and while many people saw him, they believed he was already dead. She mentioned that one Sherpa from the Brice team confirmed he was still alive, but by then it was too late to help. Her stance emphasized the individual's ultimate accountability for self-preservation in such perilous situations, rather than placing an obligation on others to rescue.

5.3. Debate on Mountaineering Ethics

The incident surrounding David Sharp's death ignited a broader ethical debate within the mountaineering community concerning the duty to rescue, the balance between individual ambition and collective responsibility, and the prevailing culture in high-altitude mountaineering.

Mountaineer David Watson, who was on the North side of Everest that season, commented to The Washington Post: "It's too bad that none of the people who cared about David knew he was in trouble... the outcome would have been a lot different." Watson believed it was possible to save Sharp, noting that Sharp himself had worked with other climbers in 2004 to save a Mexican climber who had gotten into trouble. Watson was alerted on the morning of May 16 by Phurba Tashi, who confirmed Sharp's identity after Watson showed him Sharp's passport. Around this time, a Korean team gave a radio report that the "climber in red boots" (referring to Sharp) was dead. Sharp was found with his rucksack, but his camera was missing, leaving it unknown whether he had summited.

The ethical considerations were further highlighted by a contrasting incident that occurred just a week after Sharp's death: the case of Australian climber Lincoln Hall. Hall, who was also declared dead and left on Everest, was found alive the following day by a team of four climbers-Daniel Mazur, Andrew Brash, Myles Osborne, and Jangbu Sherpa. These climbers notably abandoned their own summit attempt to stay with Hall, and with the assistance of 11 Sherpas, they successfully brought him down the mountain. Hall subsequently made a full recovery. This stark comparison intensified the discussion on human behavior and responsibility under extreme duress, raising complex moral questions about the values at play when individuals face life-or-death situations in the world's highest mountains. The incident prompted critical analysis of whether the pursuit of personal achievement had overshadowed the inherent camaraderie and mutual aid traditionally expected in mountaineering.

6. Impact and Aftermath

The death of David Sharp had lasting consequences, particularly concerning the handling of human remains on Mount Everest and the ongoing ethical discussions within the climbing world, often drawing comparisons to similar incidents.

6.1. Fate of the Body

Following his death, David Sharp's body remained on Mount Everest, a common reality for climbers who perish in the extreme conditions of the "death zone," where recovery operations are incredibly dangerous and often impossible. However, in 2007, Sharp's body was eventually removed from public view, a relatively unusual occurrence given the large number of fatalities whose remains are left on the mountain. This action reflected the practicalities and ethical considerations of dealing with fatalities on the world's highest peaks, especially when bodies become landmarks on popular climbing routes.

6.2. Comparison with Similar Incidents

Sharp's case is frequently placed within the broader context of survival and rescue ethics in mountaineering, drawing parallels with other notable incidents to deepen the discussion on ethical dilemmas. The most direct comparison is with the case of Lincoln Hall, an Australian climber who was found alive a week after Sharp's death in similar circumstances, having been declared dead and left on the mountain. Hall's survival, facilitated by a team of climbers who abandoned their own summit attempt to assist him, starkly contrasted with Sharp's fate and underscored the varying ethical choices made by individuals in extreme environments. Other incidents, such as the 1996 Mount Everest disaster and the survival story of Beck Weathers, also contribute to the ongoing dialogue about responsibility, aid, and the inherent risks of high-altitude mountaineering.