1. Overview

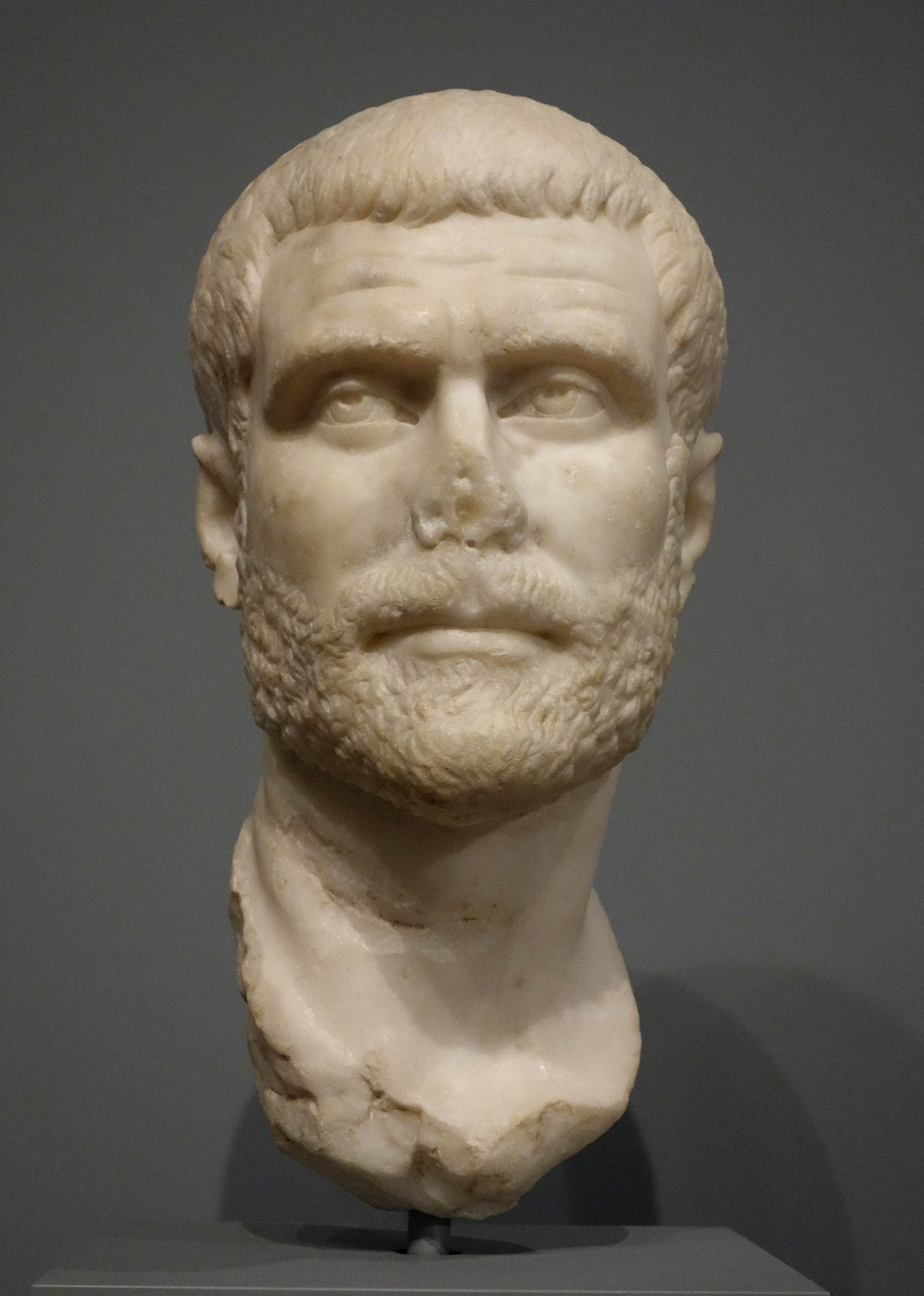

Marcus Aurelius Claudius Gothicus, also known as Claudius II, was a Roman emperor who reigned from 268 to 270. His brief but impactful rule occurred during the tumultuous Crisis of the Third Century, a period marked by external invasions, political instability, and economic decline. Despite his short time on the throne, Claudius Gothicus is widely recognized as a "savior emperor" for his crucial role in stabilizing the Roman Empire and safeguarding its citizens. He earned his cognomen, "Gothicus," after achieving a decisive victory against the Goths at the Battle of Naissus, a triumph that significantly contributed to the empire's survival. He also successfully campaigned against the Alamanni. Claudius was popular among Roman citizens and was deified after his death, which was caused by a widespread pestilence.

2. Early life and origin

Marcus Aurelius Claudius was born on May 10, 214, though some researchers suggest a later birth year of 219 or 220. The 6th-century Byzantine historian John Malalas reported that Claudius was 56 years old at the time of his death. His birthplace remains uncertain, with various accounts suggesting locations such as Sirmium in Pannonia, Naissus in Dardania (part of Upper Moesia), or generally the Illyrian region near the Danube.

Information regarding Claudius's early life and family background is scarce and often unreliable, primarily stemming from the Historia Augusta, a collection of imperial biographies known for its fabrications and praises. This source refers to him as a member of the gens Flavia, likely an attempt to forge a connection with the later emperor Flavius Valerius Constantius. The 4th-century Epitome de Caesaribus suggested he was a bastard son of Gordian II, though this claim is widely doubted by modern historians. Despite these uncertain claims of noble or imperial lineage, Claudius is generally believed to have originated from a middle-class family or humble background, rising through the military ranks rather than through aristocratic connections.

3. Military career and rise to power

Claudius's ascent to the imperial throne was rooted in a distinguished military career, culminating in his proclamation as emperor amidst the political turmoil surrounding the assassination of Gallienus.

Before coming to power, Claudius served with the Roman army, where he had a successful career and secured appointments to the highest military posts. He was a military commander under Emperor Gallienus, known for his bravery and strong leadership, which led to his rise to strategic positions within the Roman legions. The Historia Augusta states he was a military tribune under Decius (249-251), though this is doubted by historians, as such a position would imply a demotion from the higher ranks he had previously occupied. The same source describes him being sent to defend Thermopylae, an account that is likely an anachronism or an invention designed to contrast the successful pagan commander Claudius with less fortunate Christian generals. He was also reportedly rewarded by Decius after demonstrating his strength in a wrestling match at the Games of Mars.

Claudius was physically strong and known for his ferocity. A legend recounts him knocking out a horse's teeth with one punch and an opponent's teeth during a wrestling match in the 250s. Like Maximinus Thrax before him, Claudius was of "barbarian" birth. After a period of failed aristocratic Roman emperors following Maximinus's death, Claudius was the first in a series of tough "soldier emperors" who would eventually restore the Roman Empire after the Crisis of the Third Century. In 268, he was besieging Aureolus at Milan alongside Gallienus. His troops proclaimed him emperor amid charges, never proven, that he murdered his predecessor Gallienus. He was chosen by the army outside Milan to succeed Gallienus. Claudius quickly showed himself to be less bloodthirsty than some, asking the Roman Senate to spare the lives of Gallienus's family and supporters. He was less magnanimous toward Rome's enemies, and it was to this sternness that he owed his popularity.

3.1. Downfall of Gallienus

During the 260s, the Roman Empire fractured into three distinct governing entities: the core Roman Empire, the Gallic Empire, and the Palmyrene Empire. This fragmentation placed the entire Roman imperium in a precarious position. Gallienus was severely weakened by his failure to defeat Postumus in the West and his acceptance of Odaenathus's de facto independent rule in the East. By 268, this situation had changed, as Odaenathus was assassinated, most likely due to court intrigue. Upon Odaenathus's death, power fell to his younger son, who was dominated by his mother, Zenobia.

Gallienus's troubles primarily lay with Postumus, whom he could not effectively attack because his attention was required to deal with an insurrection led by Macrianus and the threats posed by invading Scythians. After four years of delay, Postumus had established significant control over the Gallic Empire. In 265, when Gallienus and his men crossed the Alps, they defeated and besieged Postumus in an unnamed Gallic city. When victory seemed imminent, Gallienus made the mistake of approaching the city walls too closely and was gravely injured, compelling him to cease his campaign against Postumus. Over the next three years, Gallienus's troubles only worsened. The Scythians successfully invaded the Balkans in the early months of 268, and Aureolus, a commander of the Roman cavalry based in Milan, declared himself an ally of Postumus and went so far as to claim the imperial throne for himself.

At this time, another invasion was taking place. In 268, a tribe or grouping called the Herulians moved through Asia Minor and then into Greece on a naval expedition. Despite this, scholars assume Gallienus's efforts were focused on Aureolus, the officer who betrayed him, and the defeat of the Herulians was largely left to his successor, Claudius Gothicus.

The death of Gallienus was surrounded by conspiracy and betrayal, as were many emperors' deaths. Different accounts of the incident have been recorded, but they generally agree that senior officials desired Gallienus's demise. According to two accounts, the prime conspirator was Aurelius Heraclianus, the Praetorian Prefect. One version tells of Heraclianus bringing Claudius into the plot, while the account given by the Historia Augusta exculpates the soon-to-be emperor and adds the prominent general Lucius Aurelius Marcianus into the plot. The removal of Claudius from the conspiracy in later narratives may be due to his subsequent role as the progenitor of the Constantinian dynasty, a fiction of Constantine I's time, suggesting that the original version from which these accounts derive was current prior to Constantine's reign. It was written that while sitting down at dinner, Gallienus was told that Aureolus and his men were approaching the camp. Gallienus rushed to the front lines, ready to give orders, when he was struck down by a commander of his cavalry. In a different and more controversial account, Aureolus forged a document in which Gallienus appeared to be plotting against his generals and ensured it fell into the hands of the emperor's senior staff. In this plot, Aurelian is added as a possible conspirator. The tale of his involvement in the conspiracy might be seen as at least partial justification for the murder of Aurelian himself under remarkably similar circumstances.

Whichever story is true, Gallienus was killed in the summer of 268, probably between July and October, and Claudius was chosen by the army outside of Milan to succeed him. Accounts tell of people hearing the news of the new emperor and reacting by murdering Gallienus's family members until Claudius declared he would respect the memory of his predecessor. Claudius had the deceased emperor deified and buried in a family tomb on the Appian Way. The traitor Aureolus was not treated with the same reverence, as he was killed by his besiegers after a failed attempt to surrender.

4. Reign

At the time of Claudius's accession, the Roman Empire was in serious danger from several incursions, both inside and outside its borders. His short reign was a period of great upheaval, characterized by external attacks, power struggles, and economic decline.

4.1. Military campaigns and victories

The most pressing threat was an invasion of Illyricum and Pannonia by the Goths. Although Gallienus had already inflicted some damage on them at the Battle of Nestus, Claudius, not long after being named emperor, followed this up by winning his greatest victory, and one of the greatest in the history of Roman arms. At the Battle of Naissus in 269, Claudius and his legions, alongside his cavalry commander, the future Emperor Aurelian, routed a massive Gothic army. The Romans took thousands of prisoners and effectively destroyed the Gothic cavalry as a fighting force. This decisive victory earned Claudius his surname of "Gothicus" (conqueror of the Goths), sometimes referred to as Gothicus MaximusLatin. The Goths were soon driven back across the Danube by Aurelian, and nearly a century passed before they again posed a serious threat to the empire.

Around the same time, the Alamanni had crossed the Alps and attacked the empire. Claudius responded quickly, routing the Alamanni at the Battle of Lake Benacus in the late fall of 268, a few months after the Battle of Naissus. For this, he was awarded the title of "Germanicus Maximus."

He then turned his attention to the Gallic Empire, which had been ruled by a pretender for the past eight years and encompassed Britain, Gaul, and the Iberian Peninsula. He won several victories and soon regained control of Hispania and the Rhone river valley of Gaul. This set the stage for the later destruction of the Gallic Empire under Aurelian. While Claudius made significant progress, he faced strong resistance from the Gallic emperor Victorinus. The Spanish provinces had already deserted the Gallic Empire and declared their loyalty to Claudius, and in southern Gaul, Placidianus had captured Grenoble. However, Placidianus halted his advance there, which helped stabilize Victorinus's position. In the next year, when Autun revolted, declaring itself for Claudius, the central Roman government made no moves to support it. As a result, the city endured a siege lasting many weeks until it was finally captured and sacked by Victorinus.

4.2. Government and administration

Claudius's reign saw a shift in the origins of influential officials within the Roman administration. Before his rule, only two emperors had come from the Balkans; afterward, until Theodosius I from Hispania would take the throne in 378, only one emperor did not hail from the provinces of Pannonia, Moesia, or Illyricum.

Several inscriptions provide insight into the government at the time. One is a dedication to Aurelius Heraclianus, the prefect involved in the conspiracy against Gallienus, from Traianus Mucianus, who also dedicated to Heraclianus's brother, Aurelius Appollinaris, the equestrian governor of the province of Thracia in 267-268 AD. Because these men shared the family name, Marcus Aurelius, a name given to those made citizens by the Constitutio Antoniniana, these men did not come from the imperial elite. A third inscription reveals the career of Marcianus, another leading general by the time Gallienus died. The fourth honors Julius Placidianus, the prefect of the vigiles. Heraclianus, Appollinaris, Placidianus, or Marcianus may not have been of Danubian origin themselves, but none of them were members of the Severan aristocracy, and all of them appear to owe their prominence to their military roles. Marcus Aurelius Probus, another future emperor, was also of Balkan background, from a family enfranchised in the time of Caracalla.

Although their influence was weakened, there were still a number of men with influence from the older Roman aristocracy. Claudius assumed the consulship in 269 with Paternus, a member of the prominent senatorial family, the Paterni, who had supplied consuls and urban prefects throughout Gallienus's reign, and thus were quite influential. In addition, Flavius Antiochianus, one of the consuls of 270, who was an urban prefect the year before, would continue to hold his office for the following year. A colleague of Antiochianus, Virius Orfitus, also the descendant of a powerful family, would continue to hold influence during his father's term as prefect. Aurelian's colleague as consul was another such man, Pomponius Bassus, a member of one of the oldest senatorial families, as was one of the consuls in 272, Junius Veldumnianus.

In his first full year of power, Claudius was greatly assisted by the sudden destruction of the imperium Galliarum. When Ulpius Cornelius Laelianus, a high official under Postumus, declared himself emperor in Germania Superior in the spring of 269, Postumus defeated him, but in doing so, refused to allow the sack of Mainz, which had served as Laelianus's headquarters. This proved to be his downfall, for out of anger, Postumus's army mutinied and murdered him. Selected by the troops, Marcus Aurelius Marius was to replace Postumus as ruler. Marius's rule did not last long though, as Victorinus, Postumus's praetorian prefect, defeated him. Now emperor of the Gauls, Victorinus was soon in a precarious position, for the Spanish provinces had deserted the Gallic Empire and declared their loyalty to Claudius, while in southern Gaul, Placidianus had captured Grenoble. Luckily, it was there that Placidianus stopped and Victorinus's position stabilized. In the next year, when Autun revolted, declaring itself for Claudius, the central government made no moves to support it. As a result, the city went through a siege, lasting many weeks, until it was finally captured and sacked by Victorinus.

In the economic sphere, Claudius faced significant challenges due to inflation and monetary chaos that plagued the Roman Empire. While no major reforms are explicitly recorded during his short reign, he reportedly sought to maintain stability by suppressing corruption at the administrative level. A medallion of Claudius commemorates his attempt to reform Roman currency, depicting three MonetaeLatin, personifications of gold, silver, and bronze. However, the state continued to be plagued by insufficient resources, with a great deal of silver used for the antoninianus being diluted again.

4.3. Foreign affairs

It is still unknown why Claudius did nothing to help the city of Autun, but sources tell us his relations with Palmyra were waning in the course of 269. An obscure passage in the Historia Augusta-s life of Gallienus states that he had sent an army under Aurelius Heraclianus to the region that had been annihilated by Zenobia. But because Heraclianus was not actually in the east in 268 (instead, at this time, he was involved in the conspiracy of Gallienus's death), this cannot be correct. But the confusion evident in this passage, which also places the bulk of Scythian activity during 269 a year earlier, under Gallienus, may stem from a later effort to pile all possible disasters in this year into the reign of the former emperor. This would keep Claudius's record of being an ancestor of Constantine from being tainted. If this understanding of the sources is correct, it might also be correct to see the expedition of Heraclianus to the east as an event of Claudius's time.

The issue at hand was the position that Odaenathus held as corrector totius orientisLatin (imparting overall command of the Roman armies and authority over the Roman provincial governors in the designated region). Vaballathus, the son of Zenobia, was given this title when Zenobia claimed it for him. From then on, tension between the two empires would only get worse. Aurelius Heraclianus's fabled arrival might have been an effort to reassert central control after the death of Odaenathus, but, if so, it failed. Although coins were never minted with the face of Odaenathus, soon after his death coins were made with the image of his son - outstripping his authority under the emperor.

Under Zabdas, a Palmyrene army invaded Arabia and moved into Egypt in the late summer. At this time, the prefect of Egypt was Tenagino Probus, described as an able soldier who not only defeated an invasion of Cyrenaica by the nomadic tribes to the south in 269, but also was successful in hunting down Scythian ships in the Mediterranean Sea. However, he did not see the same success in Egypt, for a group allied to the Palmyrene empire, led by Timagenes, undermined Probus, defeated his army, and killed him in a battle near the modern city of Cairo in the late summer of 270.

Generally, when a Roman commander is killed it is taken as a sign that a state of war is in existence, and if we can associate the death of Heraclianus in 270, as well as an inscription from Bostra recording the rebuilding of a temple destroyed by the Palmyrene army, then these violent acts could be interpreted the same way. Yet they apparently were not. As David Potter writes, "The coins of Vaballathus avoid claims to imperial power: he remains vir consularis, rex, imperator, dux RomanorumLatin, a range of titles that did not mimic those of the central government. The status vir consularisLatin was, as we have seen, conferred upon Odaenathus; the title rexLatin, or king, is simply a Latin translation of mlkSemitic languages, or king; imperatorLatin in this context simply means 'victorious general'; and dux RomanorumLatin looks like yet another version of corrector totius orientisLatin." These titles suggest that Odaenathus's position was inheritable. In Roman culture, the status gained in procuring a position could be passed on, but not the position itself. It is possible that the thin line between office and the status that accompanied it were dismissed in the Palmyrene court, especially when the circumstance worked against the interests of a regime that was able to defeat Persia, which a number of Roman emperors had failed to do. Vaballathus stressed the meanings of titles, because in the Palmyrene context, the titles of Odaenathus meant a great deal. When the summer of 270 ended, things were looking very different in the empire than they did a year before. After its success, Gaul was in a state of inactivity and the empire was failing in the east. Insufficient resources plagued the state, as a great deal of silver was used for the antoninianus being diluted again.

5. Death and succession

Claudius did not live long enough to fulfill his goal of reuniting all the lost territories of the empire. Late in 269, he had traveled to Sirmium and was preparing to go to war against the Vandals, who were raiding in Pannonia. However, he fell victim to a widespread pestilence, likely the Plague of Cyprian (possibly smallpox), and died early in 270. This epidemic had also begun spreading throughout the legions pursuing the Scythians.

Historians provide conflicting dates for Claudius's death, ranging from January to April, or August/September 270. The 6th-century Byzantine historian John Malalas states that Claudius was 56 years old at the time of his death. The last confirmed document from his reign is dated September 20, 270, although another undated papyrus could be tentatively dated to October.

Before his death, Claudius is thought to have named Aurelian as his successor. However, Claudius's brother, Quintillus, briefly seized power. Quintillus's reign was short-lived, as he was overthrown by Aurelian. The Roman Senate immediately deified Claudius as "Divus Claudius Gothicus."

6. Legacy and evaluation

Claudius Gothicus's reign, though brief, left a significant mark on the Roman Empire, earning him a lasting reputation as a pivotal figure in its recovery from the Crisis of the Third Century.

6.1. Historical evaluation

Claudius Gothicus is widely remembered as a "savior emperor" for his critical contributions to stabilizing the Roman Empire during the tumultuous Crisis of the Third Century. His firm rule and military successes, particularly his decisive victories against the Goths at the Battle of Naissus and against the Alamanni, were instrumental in securing the empire's borders and protecting its populace. He became a hero in Latin historical tradition and was held in high esteem by Greek historians like Joannes Zonaras. The Roman citizens also held him in high regard, and he was deified after his death. While some contemporary views, such as that of Zosimus, portrayed him as less grand, his overall historical evaluation emphasizes his vital role in preserving Roman governance and societal structures during a period of immense threat.

Claudius's religious policies also garnered attention. A short history of imperial Rome, De CaesaribusLatin, written by Aurelius Victor in 361, states that Claudius consulted the Sibylline Books prior to his campaigns against the Goths. Hinting that Claudius "revived the tradition of the Decii," Victor illustrates the senatorial view, which saw Claudius's predecessor, Gallienus, as too relaxed when it came to religious policies.

6.2. Connection to the Constantinian dynasty

The unreliable Historia Augusta claims a familial connection between Claudius and the later Constantinian dynasty. It reports that Claudius and his brother Quintillus had another brother named Crispus, whose niece, Claudia, reportedly married Eutropius and became the mother of Constantius Chlorus. This would make Constantius Chlorus, the father of Constantine I, Claudius's grand-nephew. The Historia Augusta further attempts to strengthen this connection by attributing the nomina "Flavius Valerius" to Claudius. However, other historians like Zonaras and Eutropius claim that Constantius Chlorus was Claudia's daughter's son, creating a slightly different lineage.

Most modern historians suspect these accounts are a genealogical fabrication, likely orchestrated by Constantine II, the grandson of Constantine I. The primary motivation behind such genealogies was to link the family of Constantine I to a well-respected and deified emperor like Claudius, thereby enhancing their imperial legitimacy and prestige. Claudius's victories, particularly over the Goths, would not only make him a hero in Latin tradition but an admirable choice as an ancestor for Constantine I, who was born at Naissus, the site of Claudius's victory in 269.

6.3. Legend of Saint Valentine

Claudius Gothicus has been traditionally linked to Saint Valentine since the Middle Ages. Contemporary records of Valentine's deeds were likely destroyed during the Diocletianic Persecution in the early 4th century. A tale of martyrdom, recorded in Passio Marii et MarthaeLatin (a work from the 5th or 6th century), refers to "Emperor Claudius." While some scholars believe this refers to Claudius II, given that Claudius I did not persecute Christians (with one exception noted by Suetonius regarding Jewish followers of "Chrestus" being expelled from Rome), it is acknowledged that Claudius II spent most of his reign warring outside Roman territory, making direct involvement in Roman persecutions less likely.

Later texts retold the legend. The Nuremberg Chronicle of 1493 describes a Roman priest, St. Valentine, being martyred during a general persecution of Christians, beaten with clubs and beheaded for aiding Christians in Rome. The Golden Legend of 1260 recounts St. Valentine's refusal to deny Christ before "Emperor Claudius" in 270, leading to his beheading. Since then, February 14 marks Valentine's Day, a day observed by the Christian church in memory of the Roman priest and physician.

6.4. Criticisms and controversies

Claudius's reign was not without its debated aspects. His decision not to assist the city of Autun during its siege by Victorinus, despite Autun declaring loyalty to Claudius, remains an unexplained point. This inaction may have also contributed to a growing quarrel with Zenobia, the queen of the Palmyrene Empire. Furthermore, the historical accounts surrounding his accession, particularly the unproven charges of his involvement in Gallienus's assassination, highlight the political intrigues of the era. The various conflicting dates for his birth and death across different historical sources also present a challenge to a definitive chronology of his life.