1. Life and career

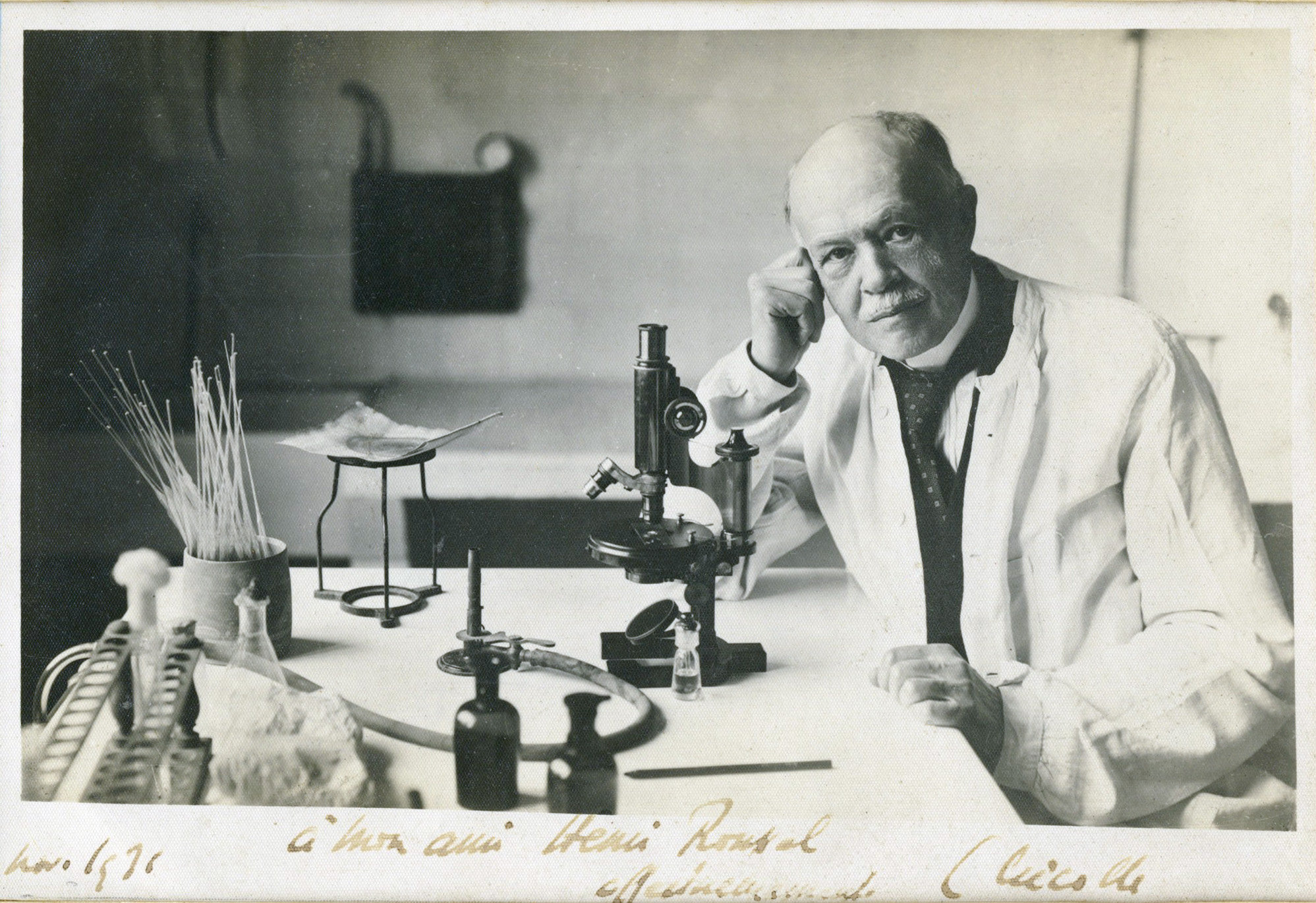

Charles Jules Henri Nicolle's life and professional journey unfolded through significant educational and professional milestones, culminating in his pivotal role as the Director of the Pasteur Institute in Tunis.

1.1. Early life and family

Charles Jules Henri Nicolle was born in Rouen, France, on 21 September 1866. He was raised in a middle-class family that deeply valued education. His father, Eugène Nicolle, was a physician at a hospital in Rouen and was an early influence on Charles's education, particularly in biology. Charles had two siblings: an elder brother, Maurice Nicolle, who became a medical microbiologist, a professor at the Pasteur Institute in Paris, and the Director of the Bacteriological Institute of Constantinople; and a younger brother, Marcel Nicolle, an art critic. In 1895, Charles Nicolle married Alice Avice. They had two children, Marcelle (born 1896) and Pierre (born 1898), both of whom later pursued careers in the medical field. Nicolle himself became deaf around this time.

1.2. Education and early professional career

Nicolle received his early education at the Lycée Pierre Corneille in Rouen. He then pursued his medical studies and obtained his medical degree from the Pasteur Institute of Paris in 1893, specializing in bacteriology. After completing his degree, he returned to Rouen, where he served as a member of the Medical Faculty until 1896. From 1896 to 1902, he held the position of Director of the Bacteriological Laboratory in Rouen. During these early years, his expertise in bacteriology began to solidify, setting the stage for his future groundbreaking discoveries.

1.3. Directorship of the Pasteur Institute in Tunis

In 1903, Charles Nicolle was appointed Director of the Pasteur Institute of Tunis, a position he held for 33 years until his death in 1936. This period marked a pivotal chapter in his career and in the history of medical research. Before his arrival, the Pasteur Institute in Paris maintained a dominant role in French research, adhering to Pasteurian principles that emphasized non-profit medical aid, research, and public service.

Under Nicolle's strategic leadership, the Pasteur Institute in Tunis rapidly evolved into an international center for the production of vaccines and a hub for medical research. His success stemmed from a significant departure from traditional Pasteurian ideology; Nicolle actively cultivated relationships with local Tunisian and French healthcare officials and restructured the Institute's operations. He devised a system where other medical functions, such as patient care, would generate revenue to financially support the Institute's ongoing laboratory research. This innovative approach granted the Institute autonomy, allowing it to operate without sole reliance on public or governmental funds.

As the Institute achieved greater financial stability, Nicolle focused on addressing prevalent diseases and public health concerns in the local region. He also ensured the sharing of research findings and resources with the Paris Institute and expanded the Institute's scientific publications by establishing the journal Archives de l'Institut de Tunis. Furthermore, Nicolle became a crucial point of contact for the French government during public health crises, notably intervening in the malaria epidemic of 1906 and the cholera outbreak of 1907. It was during his directorship in Tunis that he undertook his most defining work: the discovery of the transmission method of typhus and the development of vaccines.

2. Key research and discoveries

Charles Nicolle made seminal contributions to the fields of bacteriology and parasitology, with his most significant work focusing on infectious disease transmission and vaccine development.

2.1. Discovery of typhus transmission

Nicolle's groundbreaking discovery of the transmission route of epidemic typhus began with meticulous observation at the French hospital in Tunis. He noted that while patients with epidemic typhus could easily infect others both inside and outside the hospital, and their soiled clothes appeared to spread the disease, they were no longer infectious once they had undergone a hot bath and changed into clean clothes. This crucial observation led him to deduce that lice were the most probable vector for epidemic typhus.

At the time, studying typhus transmission was challenging because the parasite required a human host, limiting research to epidemic periods. However, Nicolle identified the common chimpanzee as a suitable alternate host due to its genetic similarity to humans. In June 1909, he put his theory to the test. He infected a chimpanzee with typhus, then retrieved lice from the infected animal and placed them on a healthy chimpanzee. Within ten days, the second chimpanzee also developed typhus. After repeating this experiment, Nicolle confirmed his hypothesis: lice were indeed the carriers of the disease. As his research progressed, he later found that guinea pigs were equally susceptible to infection, and being smaller and more cost-effective, they became his preferred model organism.

Further research by Nicolle revealed that the primary mode of transmission was not louse bites themselves, but rather the louse's excrement. Infected lice typically turn red and die after a few weeks, but in the interim, they excrete a large number of microbes. If even a small quantity of this excrement comes into contact with the skin or eye, an infection can occur. Nicolle's work was instrumental not only in containing typhus epidemics prevalent in North Africa and the Mediterranean Basin but also in helping scientists differentiate louse-borne typhus from murine typhus, which is transmitted by fleas. His findings also proved invaluable in preventing typhus outbreaks during World War I, which began in 1914.

2.2. Vaccine development efforts

Nicolle embarked on efforts to develop a vaccine for epidemic typhus, hypothesizing that a simple vaccine could be created by crushing infected lice and mixing them with blood serum from recovered patients. He first tested this experimental vaccine on himself. Upon remaining healthy, he administered it to a few children, reasoning that their immune systems might respond better. While these children developed typhus, they subsequently recovered. Despite these attempts, Nicolle did not succeed in developing a practical and widely applicable vaccine against typhus. The next significant step in typhus vaccine development would be achieved by the biologist Rudolf Weigl in 1930, though Weigl's method was initially not suitable for mass production and carried risks, requiring subsequent improvements for safety and efficiency.

Despite the challenges with the typhus vaccine, Nicolle made several other critical discoveries in the field of vaccination. He was the first to identify sodium fluoride as an effective reagent for sterilizing parasites, making them non-infectious while simultaneously preserving their structure for vaccine use. Utilizing this method, he successfully developed vaccines for gonorrhea, certain staphylococcal infections, and cholera. These vaccines were not only utilized extensively throughout France but were also distributed worldwide. Furthermore, he introduced a vaccination for Malta fever, also known as Mediterranean gastric fever.

2.3. Other scientific contributions

Beyond his pivotal work on typhus and vaccine development, Charles Nicolle conducted extensive research and made significant contributions to the understanding of various other diseases. His studies encompassed a wide range of infectious conditions, including Malta fever, cancer, scarlet fever, rinderpest, measles, influenza, tuberculosis, and trachoma.

He was also credited with the discovery of the transmission method for tick fever. In the realm of parasitology, Nicolle notably identified the parasitic organism Toxoplasma gondii within the tissues of the gundi (Ctenodactylus gundi), a parasite commonly observed in patients with AIDS. Additionally, he studied the parasitic microorganism Leishmania tropica, which is known to cause the skin condition referred to as Oriental sore. His broad scope of research solidified his reputation as a versatile and impactful microbiologist.

3. Writings and philosophy

Charles Nicolle was not only a prolific scientist but also an accomplished author who contributed to academic and literary fields, reflecting his diverse intellectual interests in bacteriology, biology, and philosophy.

3.1. Scientific and philosophical works

Throughout his life, Nicolle authored a number of significant non-fiction books focusing on bacteriology, biology, and philosophy. These works often explored profound questions about the nature of disease and human existence. His major scientific and philosophical publications include:

- Naissance, vie et mort des maladies infectieusesFrench (Birth, Life, and Death of Infectious Diseases, 1930)

- Biologie de l'inventionFrench (Biology of Invention, 1932)

- Introduction à la carrière de la médecine expérimentalesFrench (Introduction to the Career of Experimental Medicine, 1932)

- Le Destin des Maladies infectieusesFrench (The Destiny of Infectious Diseases, 1933)

- L'Expérimentation en médecineFrench (Experimentation in Medicine, 1934)

- La Nature, conception et morale biologiquesFrench (Nature, Biological Conception and Morality, 1934)

- Responsabilités de la MédecineFrench (Responsibilities of Medicine, 1935 and 1936, in two parts)

- La Destinée humaineFrench (Human Destiny, 1936)

3.2. Literary works

Beyond his scientific and philosophical treatises, Nicolle also ventured into fiction and other literary genres, demonstrating a broader intellectual curiosity. His literary contributions include:

- La chronique de Maitre Guillaume HeurtebiseFrench (The Chronicle of Master Guillaume Heurtebise, 1903)

- Le Pâtissier de BelloneFrench (The Pastry Chef of Bellone, 1913)

- Les Feuilles de la sagittaireFrench (The Leaves of the Sagittaria, 1920)

- La NarquoiseFrench (The Sly One, 1922)

- Les Menus Plaisirs de l'ennuiFrench (The Minor Pleasures of Boredom, 1924)

- Marmouse et ses hôtesFrench (Marmouse and its Guests, 1927)

- Les deux LarronsFrench (The Two Thieves, 1929)

- Les Contes de MarmouseFrench (The Tales of Marmouse, 1930)

4. Personal life and beliefs

Charles Nicolle, while maintaining a rich scientific career, also navigated significant personal and spiritual introspection. Although baptized a Catholic, he left the faith at the age of twelve. However, beginning in 1934, Nicolle experienced spiritual anxiety. Following communication with a Jesuit priest, he was reconciled with the Catholic Church in August 1935, less than a year before his passing.

5. Death

Charles Jules Henri Nicolle died on 28 February 1936, in Tunis, Tunisia, where he had served as the Director of the Pasteur Institute for over three decades.

6. Honors and legacy

Charles Nicolle's pioneering work in microbiology and public health earned him numerous accolades and left a lasting impact on scientific understanding and disease control strategies worldwide.

6.1. Awards and recognition

The pinnacle of Charles Nicolle's academic honors was the awarding of the Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine in 1928, recognizing his decisive work on the transmission of epidemic typhus. In addition to the Nobel Prize, he was elected a member of the French Academy of Sciences in 1929, further acknowledging his significant contributions to the scientific community.

6.2. Influence and historical evaluation

Nicolle's work profoundly influenced the fields of bacteriology, epidemiology, and public health. His identification of lice as the vector for epidemic typhus was a pivotal discovery that revolutionized disease control, enabling the implementation of effective hygiene measures to curb outbreaks. This finding was particularly crucial during World War I, helping to prevent widespread typhus epidemics among soldiers and civilians. His strategic management of the Pasteur Institute in Tunis, turning it into an internationally recognized center for research and vaccine production, demonstrated his foresight in promoting scientific advancement and public health initiatives. His efforts led to the successful development and global distribution of vaccines for diseases such as gonorrhea, staphylococcal infections, and cholera, showcasing his practical application of scientific knowledge for societal benefit. Nicolle's holistic approach to understanding infectious diseases, encompassing their life cycle, transmission, and potential for prevention, has been historically evaluated as a major step forward in controlling epidemics and improving global public health.

6.3. Tributes and memorials

Charles Nicolle's life and work have been commemorated through various literary tributes. Several significant books have been written about his contributions to science and medicine:

- Jacques Debray authored Charles Nicolle. Enfant de Rouen. Médecin. Savant. Écrivain (Charles Nicolle. Child of Rouen. Doctor. Scientist. Writer), published in Rouen in 1993.

- Maurice Huet wrote Le Pommier et l'Olivier. Charles Nicolle. Une biographie. 1866-1936 (The Apple Tree and the Olive Tree. Charles Nicolle. A Biography. 1866-1936), published in Montpellier in 1995.

- Fernand Lot's work, Charles Nicolle: Un Grand Biologiste (Charles Nicolle: A Great Biologist), was published in Paris in 1946.

- Germaine Lot contributed Charles Nicolle et la biologie conquérante (Charles Nicolle and Conquering Biology), published in Paris in 1961.

- Mélanie Mataud and Pierre-Albert Martin co-authored La Médecine rouennaise à l'époque de Charles Nicolle. De la fin du XIXe aux années 1930 (Rouen Medicine in the Era of Charles Nicolle. From the End of the 19th Century to the 1930s), published in Luneray in 2003.

7. See also

- Epidemic typhus

- Pasteur Institute

- Rudolf Weigl

- Vector (epidemiology)

- History of medicine