1. Early Life and Background

Charles Frederick's early life was shaped by his noble lineage, the early death of his father, and the political turbulence of the Great Northern War. His upbringing was overseen by his mother and later his great-grandmother, both of whom played a role in fostering his claim to the Swedish throne.

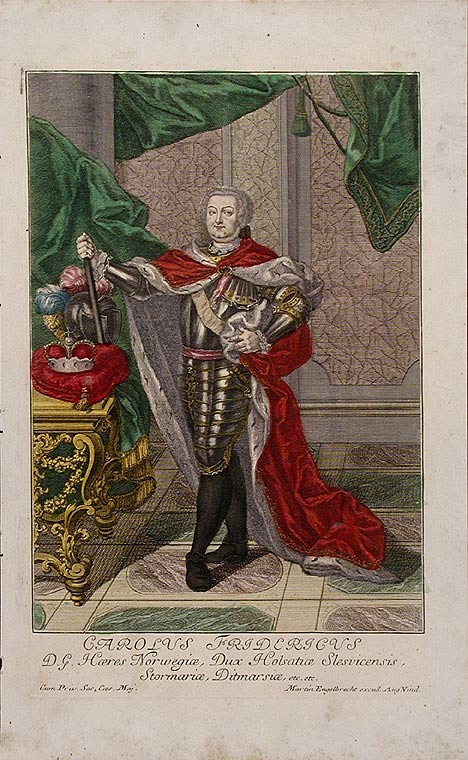

1.1. Birth and Family

Charles Frederick was born in Sweden on April 30, 1700. He was the only son of Frederick IV, Duke of Holstein-Gottorp, and his consort, Hedvig Sophia of Sweden. His mother, Hedvig Sophia, was a daughter of Charles XI of Sweden, making Charles Frederick the nephew of the reigning Swedish monarch, Charles XII of Sweden. His family belonged to the House of Oldenburg, a prominent European dynasty that also ruled Denmark at the time. His first cousin, Adolph Frederick, who later became King of Sweden, was the son of his father's younger brother.

1.2. Childhood and Upbringing

Charles Frederick's father died in 1702 at the Battle of Kliszów, when Charles Frederick was only two years old. His mother, Hedvig Sophia, became his regent, and they continued to reside in Stockholm, having been offered refuge there by his maternal uncle, Charles XII, during the outbreak of the Great Northern War. His mother reportedly raised him with a tender but firm hand. However, she passed away in 1708 when Charles Frederick was just eight years old. He was then placed under the care of his great-grandmother, Hedwig Eleonora of Schleswig-Holstein-Gottorp, who was his mother's paternal grandmother. It is said that Hedwig Eleonora spoiled him considerably, which contributed to him developing a passive and indolent character. Both his mother and later Hedwig Eleonora actively supported and worked towards his recognition as the heir to the childless Charles XII of Sweden. The actual daily governance of the Duchies of Schleswig and Holstein was largely left to administrators during his minority.

1.3. Succession to the Dukedom

Upon the death of his father, Frederick IV, in 1702, Charles Frederick inherited the ducal title of Schleswig-Holstein-Gottorp at the age of two. He nominally co-ruled the Duchy of Holstein, a Holy Roman imperial fief, and the Duchy of Schleswig, a Danish fief, with his father's cousin, Frederick IV of Denmark. However, this co-rule was under guardianship until 1717, and his status in Schleswig was as a vassal to the Danish-Norwegian king.

2. Rule as Duke of Schleswig-Holstein-Gottorp

Charles Frederick's reign as Duke was significantly impacted by the ongoing conflicts of the Great Northern War, which led to substantial territorial losses for his duchies.

2.1. Territorial Situation and Loss

During the Great Northern War, Charles Frederick's guardians sided with Sweden against Denmark-Norway. This allegiance had severe consequences for his territories. Danish troops ravaged the Gottorp ducal share in the duchies and, by 1713, conquered its northern portions. This included the ancestral ducal seat of Gottorp Castle, located near Schleswig city in the eponymous duchy. In 1721, Frederick IV of Denmark, who had formally invested Charles Frederick with the ducal title in Schleswig in 1702, officially revoked this fief. This act formalized the loss of Charles Frederick's ducal share in Schleswig.

3. Swedish Succession Claim

Charles Frederick was a prominent claimant to the Swedish throne, a position that defined much of his early political maneuvering, though he ultimately failed to secure it.

3.1. Claim to the Swedish Throne

Charles Frederick was considered a legitimate claimant to the Swedish throne throughout his life as the closest male relative to the childless Charles XII of Sweden. He first met his uncle Charles XII in 1716. In 1717, he was declared to have reached legal majority and was subsequently given some military responsibilities. Following the death of his maternal uncle and second cousin, Charles XII, in 1718, Duke Charles Frederick was put forward as a claimant to the throne.

3.2. Exclusion from Succession

Despite his strong claim, Charles Frederick failed to secure the Swedish throne. His aunt, Ulrika Eleonora the Younger (1688-1741), managed to claim the throne for herself. She asserted that her elder sister, Hedvig Sophia (Charles Frederick's mother), had not obtained the necessary consent of the Parliamentary Estates for her marriage to Frederick IV, as required by the laws of succession laid down in Norrköpings arvförening. Charles Frederick's supporters countered this by arguing that the absolute monarchy established by his grandfather, King Charles XI, rendered such marriage clauses irrelevant.

Upon receiving the news of his uncle's death, Charles Frederick was reportedly too grief-stricken to take immediate action. In contrast, Ulrika Eleonora's husband, Frederick I, who was also present with Charles Frederick in Tistedalen, quickly moved to assist her in claiming the throne. When confronted by Ulrika Eleonora, Charles Frederick was compelled by Arvid Horn to acknowledge her as queen. He requested to be granted the title of Royal Highness and to be recognized as her heir. However, when this title was instead bestowed upon Ulrika Eleonora's husband, Charles Frederick departed from Sweden in 1719. Although he was eventually granted the title of Royal Highness in his absence in 1723, his increasingly pro-Russian political stance made him an unacceptable candidate for the Swedish throne.

The so-called Holstein Party in Sweden continued to advocate for Charles Frederick's claims, making preparations and awaiting the death of the childless Ulrika Eleonora. However, Charles Frederick died before his aunt, passing his claims to his infant son. By this time, Sweden had enacted new laws of succession that explicitly excluded Charles Frederick and his heirs due to their Russian political alignment, as relations between Russia and Sweden were strained. This exclusion of Charles Frederick and his progeny from the Swedish succession ultimately prevented a personal union between Sweden and Russia, especially as his only child would later become Tsar Peter III. The "Hat faction" in Sweden subsequently elected Charles Frederick's first cousin, Adolph Frederick, who belonged to the same Oldenburg dynasty, as the Crown Prince of Sweden.

4. Relationship with the Russian Imperial Family

Charles Frederick's most significant dynastic achievement was his marriage into the Russian Imperial family, which ultimately led to his son's ascension to the Russian throne.

4.1. Marriage to Anna Petrovna

After withdrawing from Sweden, Charles Frederick eventually settled in Russia. In May 1725, he married Grand Duchess Anna Petrovna, the elder daughter of Tsar Peter the Great and Marta Skavronskaya (who later became Empress Catherine I of Russia). Peter the Great viewed this marriage as politically advantageous. Charles Frederick was officially engaged to Anna by Tsar Peter himself. Following Peter's death in 1725, Empress Catherine I provided Charles Frederick with a position in the council, his own court, a palace, and an income. Despite the political benefits, Anna Petrovna was reportedly not enthusiastic about the marriage, largely due to Charles Frederick's reputation for consorting with prostitutes.

4.2. Son Peter III and Russian Succession

Charles Frederick and Anna Petrovna had one son, Charles Peter Ulrich, who was born in 1728. As the commander of the palace guard in Saint Petersburg and a member of the Supreme Privy Council, Charles Frederick attempted to secure his wife's succession to the Russian throne upon the death of her mother, Empress Catherine I, in 1727. This attempt, however, was unsuccessful.

Despite this setback, his son, Charles Peter Ulrich, who succeeded to the ducal share of Holstein in 1739, eventually became the Russian Tsar in 1762, reigning as Peter III. Charles Frederick's persistent efforts to secure his son's position in the Russian line of succession ultimately bore fruit. However, Peter III's reign was short-lived, partly due to the political and personal traits inherited or influenced by his father's actions and character, leading to his overthrow by his wife, Catherine II. For instance, Peter III's controversial decision in 1762 to prepare Russian troops to reconquer the lost territories of Schleswig from Denmark-Norway, a motivation stemming from his father's opposition to the Treaty of Frederiksborg, contributed to his unpopularity and subsequent downfall.

5. Later Life and Death

Following his dynastic efforts in Russia, Charles Frederick spent his final years primarily focused on his son's future rather than the direct governance of his ducal territories.

5.1. Life in Holstein-Gottorp

In 1727, Charles Frederick and Anna Petrovna departed for the Gottorp ducal share of Holstein, taking up residence in Kiel Castle. Anna Petrovna died in Kiel in 1728, shortly after the birth of their son. Charles Frederick spent the remainder of his life in Holstein-Gottorp, residing in Kiel. His primary concern during these years was to secure his son's succession to the Russian throne. While he continued to support his followers in Sweden, he reportedly paid little attention to the direct governance and affairs of Holstein-Gottorp itself.

5.2. Death

Charles Frederick died on June 18, 1739, in Rohlfshagen, a small village in Saxony which is today part of the town of Rümpel. His death occurred before a member of the Holstein-Gottorp family ascended either the Swedish or the Russian throne. He was buried in the Cloister Church at Bordesholm.

6. Legacy and Impact

Charles Frederick's most enduring legacy lies in his pivotal role in shaping the future of the Russian Empire through his son, Peter III, and the establishment of a new imperial dynasty.

6.1. Ancestor of the Romanov Dynasty

Charles Frederick's marriage to Anna Petrovna and the subsequent birth of their son, Charles Peter Ulrich, proved to be a turning point in Russian dynastic history. When his son ascended to the Russian throne as Peter III of Russia in 1762, it marked the establishment of the House of Holstein-Gottorp-Romanov. This new imperial line, though often still referred to simply as the Romanov dynasty, was patrilineally descended from Charles Frederick. As such, he became the direct male-line ancestor of all subsequent Russian emperors, from Peter III through Nicholas II, with the exception of Catherine II herself, who was Peter III's wife. This lineage profoundly impacted the course of Russian history for over a century and a half.

6.2. Historical Assessment

Charles Frederick's life was a complex interplay of inherited claims, political maneuvering, and personal characteristics. While he was a legitimate claimant to the Swedish throne, his perceived arrogance, lack of responsibility, and later his pro-Russian policies ultimately led to his exclusion from the Swedish succession. His opposition to the Treaty of Frederiksborg and his desire to reclaim lost territories from Denmark-Norway significantly influenced his son Peter III, contributing to Peter's unpopular policies and ultimately his downfall. Charles Frederick's personal traits, described as passive and indolent, may have been passed on or influenced his son's character, which also played a role in Peter III's short and tumultuous reign. Despite his personal shortcomings and political failures in Sweden, Charles Frederick's most significant contribution to European royal history was his successful dynastic alliance with the Russian Imperial family, which ensured his lineage would occupy the Russian throne for generations, thus cementing his place as a crucial figure in the history of the Romanov dynasty.