1. Overview

Chandragupta Maurya, also known as चन्द्रगुप्त मौर्यCandragupta MauryaSanskrit, was the founder and first emperor of the Maurya Empire in ancient India. His reign, generally placed from 322 BCE to 297 BCE, marked a pivotal period in Indian history, as he is credited with unifying much of the Indian subcontinent under a single administration. Rising to power in the wake of Alexander the Great's departure and the subsequent fragmentation of regional powers, Chandragupta successfully challenged both the Greek governors in the northwest and the powerful Nanda dynasty in the Magadha region.

Under his rule, the Maurya Empire initiated an era of economic prosperity, administrative reforms, and significant infrastructure development, including extensive irrigation systems and a vast network of roads. While his governance is sometimes described as strong and centralized, particularly in ancient Greek accounts, the empire also fostered religious pluralism, respecting various traditions such as Brahmanism, Buddhism, Jainism, Ajivika, Zoroastrianism, and the Greek pantheon. Chandragupta's legacy as a visionary unifier and the first emperor of a vast Indian empire remains significant in Indian historiography. The precise details of his origins, early life, and death are debated among scholars, drawing upon varied and sometimes conflicting accounts from Greco-Roman, Brahmanical, Buddhist, and Jain sources.

2. Historical Sources

Information about Chandragupta Maurya's life and reign is derived from a variety of ancient sources, including Greco-Roman accounts, Brahmanical texts (Puranas, Mudrarakshasa), Buddhist scriptures (Mahavamsa, Dipavamsa), and Jain texts (Parishishtaparvan, Brihatkathakosa). These sources, written centuries after his death, often vary significantly in detail and perspective, presenting challenges for historians in reconstructing a definitive chronology and narrative.

2.1. Greco-Roman Accounts

Greco-Roman sources, primarily from the 1st century BCE to the 2nd century CE, offer fragmented but crucial insights into Chandragupta's interactions with the Greek presence in India. The Roman historian Justin, in his 2nd-century CE work, is the only one to directly mention Chandragupta, referring to him as "Sandracottos" or "Sandrocottus." Justin describes Chandragupta as a man of humble origin who, after offending the Nanda king and fleeing, was inspired by miraculous omens (such as a wild lion licking him and a wild elephant submitting to him as a mount before a battle) to aspire to royalty. Justin states that Chandragupta "achieved India's freedom" from Greek rule but then "transformed liberation in servitude" by oppressing the very people he had freed.

Other Greek authors, such as Plutarch, mention that Chandragupta, as a young man, encountered Alexander the Great during the latter's invasion of India (circa 326-325 BCE). Plutarch reports that Chandragupta later remarked that Alexander narrowly missed conquering the country because its king (presumably Dhana Nanda) was widely hated. Contemporary Greek ambassador Megasthenes, who served in Chandragupta's court, wrote extensively about India in his work Indica, though only fragments survive through later authors like Strabo, Diodorus, Arrian, Pliny the Elder, Plutarch, and Justin. These fragments provide general impressions of his rule and the state of India.

2.2. Indian Religious Texts and Legends

Indian religious texts and legends provide varying narratives of Chandragupta's life, often serving to legitimize or associate him with specific religious traditions.

- Brahmanical Puranas: The Puranas, compiled during the Gupta period (4th-6th century CE), depict the Nanda and Maurya rulers as illegitimate due to their supposed Shudra (lowest social class) background. They portray the Nanda king as cruel and against dharma and shastras, crediting Chanakya (referred to as Kautilya) with restoring just rule. The Arthashastra, a treatise on statecraft attributed to Chanakya, is also sometimes considered a source, though its dating and direct applicability to Chandragupta's reign are debated, with many scholars now placing its composition between the 1st and 3rd centuries CE. Later Brahmanical narratives, such as Vishakhadatta's Mudrarakshasa (4th-8th century CE), Somadeva's Kathasaritsagara (11th century), and Kshemendra's Brihatkathamanjari (11th century), also include legends about Chandragupta and Chanakya.

- Buddhist Texts: The earliest Buddhist sources, such as the Sri Lankan Pali texts Dipavamsa, Mahavamsa, and Mahavamsa Tika (4th century CE or later), describe Chandragupta as being of Kshatriya (warrior/noble class) origin. These texts, written about seven centuries after his dynasty ended, claim that both Chandragupta and his grandson Ashoka belonged to the Moriya tribe, a branch of Buddha's Shakya noble family. They attempt to link the Maurya dynasty directly to the Buddha. The epithet Maurya is explained by the presence of peacocks, or Mora in Pali, in their secluded Himalayan kingdom. Some Buddhist texts also mention a city named "Moriya-nagara" where buildings resembled peacocks. They uniformly present Chanakya as his Brahmin counselor who helped him become king at Pataliputra.

- Jain Texts: The 12th-century Digambara Jain text Parishishtaparvan by Hemachandra is the main and earliest complete Jain legend of Chandragupta, composed nearly 1,400 years after his death. It details Chandragupta's interaction with Chanakya and later legends of his conversion to Jainism. Other Digambara Jain sources, such as Harisena (Jain monk)'s Brhatkathakosa (circa 10th century), mention his renunciation and death by Sallekhana (fasting unto death) in Karnataka. However, the Brhatkathakosa suggests his disciple Chandragupta migrated from Ujjain, raising questions about whether this refers to a different person.

2.3. Analysis of Sources and Dating

Scholarly debates highlight the inconsistencies and challenges in precisely dating Chandragupta's life and reign. None of the ancient texts provide his exact birth year. Plutarch's account of Chandragupta seeing Alexander the Great implies a birth after 350 BCE, though some early interpretations of Justin's text, suggesting a meeting between Chandragupta and Alexander, have been corrected by modern philology to refer to the Nanda king.

The start and end years of Chandragupta's reign are also unclear. Some Hindu and Buddhist texts suggest he ruled for 24 years. Buddhist sources state his rule began 162 years after the Buddha's death, but the varying dates for Buddha's parinirvana make this an inconsistent chronological marker. Similarly, Jain sources provide different gaps between Mahavira's death and Chandragupta's accession, further complicated by debates over Mahavira's death date. These inconsistencies across different religious traditions cast doubt on their precise chronologies.

Modern historians often assign Chandragupta's reign to circa 322-298 BCE. Some scholars, like Upinder Singh, date his rule from 324 or 321 BCE to 297 BCE, while Kristi Wiley suggests 320 to 293 BCE. However, other scholars re-evaluating Justin's text propose that Chandragupta might have gained power, and possibly become the first Mauryan king, between circa 311 and 305 BCE, which would imply that his campaigns in Punjab occurred after his ascension to the Nanda throne. The exact circumstances and date of his death are also disputed, with some scholars dating his abdication to circa 298 BCE and his death between 297 and 293 BCE.

3. Biography

Chandragupta Maurya's personal background and early life are largely shrouded in legend, with historical information being scarce. However, various religious traditions offer differing accounts of his origins and formative experiences.

3.1. Name and Titles

In Greco-Roman accounts, Chandragupta is consistently referred to by various names such as ΣανδράκοπτοςSandrákoptosGreek, Modern, ΣανδράκοττοςSandrákottosGreek, Modern, and ΑνδροκόττοςAndrokóttosGreek, Modern. The British orientalist and philologist Sir William Jones was the first to propose in 1793 that the "Sandracottus" of Greek and Roman sources was indeed Chandragupta Maurya from Sanskrit literature. This identification was crucial as it provided a "sheet anchor" for Indian chronology, allowing for the synchronization of Indian and Greco-Roman historical dates for the first time.

The Sanskrit play Mudrarakshasa refers to Chandragupta by several epithets, including "Chanda-siri" (Chandra-shri) and "Piadamsana" (Priya-darshana), the latter being similar to "Priyadasi," an epithet used by his grandson, Ashoka. Another epithet, "Vrishala," found in Indian epics and law books, is used to refer to non-orthodox individuals. While one theory suggests it might derive from the Greek royal title "Basileus," there is no concrete evidence, as Indian sources apply it to various non-royals, including wandering teachers and ascetics.

3.2. Early Life and Background

Historical information about Chandragupta's youth is limited to legends. Medieval commentators offer various theories about his family background. One account suggests he was the son of a Nanda king and a wife named Mura, or alternatively, a concubine. The Sanskrit dramatic text Mudrarakshasa describes him as Vrishala and Kula-Hina, meaning "not descending from a recognized clan or family," implying humble origins. While "Vrishala" can mean "son of a Shudra" (lowest social class), it can also mean "best of kings," leading to debates among historians regarding his social standing. Regardless, the common theme in Hindu sources is that Chandragupta came from a humble background and, with Chanakya's guidance, became a righteous king beloved by his subjects.

The 11th-century Kashmiri Hindu texts, Kathasaritsagara and Brihat-Katha-Manjari, propose a short Nanda lineage, stating that Chandragupta was the son of Purva-Nanda, the elder Nanda king based in Ayodhya.

3.3. Chanakya's Influence and Education

A central figure in Chandragupta's rise was his mentor and chief minister, Chanakya, a renowned strategist and philosopher often considered the author of the Arthashastra. Legends about Chanakya consistently portray him as Chandragupta's guide and spiritual teacher, complementing the image of a chakravartin (universal monarch).

According to the Digambara Jain legend by Hemachandra, Chanakya was a Jain layperson and a Brahmin. Jain monks prophesied at his birth that he would help make someone an emperor. Chanakya, believing this prophecy, arranged to adopt a baby boy from a peacock-breeding community chief. He later reclaimed the young Chandragupta, whom he then educated and trained. Together, they recruited soldiers to attack the Nanda Empire, eventually succeeding and establishing Pataliputra as their capital.

Buddhist and Hindu legends offer slightly different versions of their initial meeting. They generally describe a young Chandragupta playing a mock game of a royal court near the Vinjha forest, where Chanakya observed him issuing orders to others. Impressed, Chanakya bought Chandragupta from a hunter and adopted him. He then enrolled Chandragupta in Taxila, where he received a comprehensive education in the Vedas, military arts, law, and other shastras (sacred texts). One Buddhist legend also suggests that Chanakya, insulted by Dhana Nanda, swore to destroy the Nanda dynasty, fled Pataliputra, and subsequently encountered Chandragupta.

3.4. Early Religious Affiliation

Contemporary Greek evidence indicates that Chandragupta continued to perform Vedic sacrifices and Brahmanical rituals throughout his reign, delighting in activities like hunting. This contrasts with later Jain legends that developed approximately 900 years after his time, which suggest his conversion to Jainism. His court also hosted major festivals characterized by processions of elephants and horses, indicating a patronage of traditional religious practices.

4. Rise to Power

Chandragupta Maurya's ascent to power was a complex process involving military campaigns and strategic alliances that ultimately led to the establishment of the Maurya Empire, marking a significant turning point in Indian history.

4.1. Historical Context

Before Chandragupta's emergence, the Indian subcontinent experienced a period of significant political flux. Around 350 BCE, the Nanda Empire, centered in Magadha, had become the dominant power in northern India after a series of internal conflicts among the smaller janapadas. This powerful kingdom was known for its vast army and treasury.

The political landscape was further complicated by Alexander the Great's invasion of the Northwest Indian subcontinent. However, Alexander aborted his Indian campaign in 325 BCE due to a mutiny among his troops, caused by the daunting prospect of facing another large empire, presumably the Nanda Empire. Upon his departure, Alexander left the northwestern territories of the Indus Valley under the control of Greek governors. Alexander's death in 323 BCE in Babylon further destabilized the region, leading to wars among his generals and creating a power vacuum that Chandragupta Maurya would exploit.

4.2. Conquest of Northwest India

Following Alexander's death, a period of unrest and localized warfare erupted in the Punjab region as the Greek governors struggled to maintain control. The Roman historian Justin states that after Alexander's demise, Greek prefects in India were assassinated, leading to the liberation of the local populace from Greek rule. This revolt was spearheaded by Chandragupta, who then, according to Justin, established an oppressive regime himself after seizing the throne, effectively transforming liberation into a new form of servitude.

Justin further mentions that Chandragupta assembled an army. While early translators interpreted his description as a "body of robbers," it more accurately referred to mercenary soldiers, hunters, or even the un-kinged people of Punjab, from whom Chandragupta recruited the core of his forces. The nature of Chandragupta's initial relationship with these Greek governors remains largely unknown, though some accounts suggest he was a rival of Alexander's successors in northwestern India.

Alain Daniélou elaborates on the chaotic situation, noting that Greek satraps like Nicanor and Philip were assassinated. Peithon, another satrap, withdrew to Arachosia. Eudemus left India with a large force of elephants but was later defeated and executed. This political vacuum and the weakened Greek presence made it relatively easy for Chandragupta to annex the Greek kingdoms, as the ground had already been prepared for him.

Buddhist texts like Mahavamsa Tika and Jain texts such as Parishishtaparvan describe Chandragupta and Chanakya raising an army from various regions, including mercenary soldiers, and forming an alliance with a local king named Parvataka, to resist the Greeks. Some scholars suggest that Chandragupta also recruited and incorporated local military republics, like the Yaudheyas, who had previously resisted Alexander's empire. The precise chronology of Chandragupta's activities in Punjab-whether before or after his conquest of Magadha-remains uncertain, though some place his arrival in Punjab around 317 BCE.

4.3. War against the Nandas and Seizure of Pataliputra

Before his final victory over the Nandas, Chandragupta had offended the Nanda king, Dhana Nanda, who ordered his execution. Chandragupta narrowly escaped, leading him to seek safety and subsequently to his rise as a leader. The Mudrarakshasa states that Chanakya, insulted by the Nanda king, swore to destroy the Nanda dynasty. The Jain version similarly describes Chanakya being publicly humiliated by the Nanda ruler. In any case, Chanakya then found Chandragupta, and together they initiated a war against the Nanda Empire.

According to some accounts, Chandragupta's army, after defeating the Greeks, turned its attention to the unpopular Nanda dynasty. They first conquered the Nanda's outer territories before advancing on Pataliputra, the capital city. Some sources suggest they employed guerrilla warfare methods, possibly with the aid of mercenaries from conquered areas, to seize the capital. With the defeat of Dhana Nanda, Chandragupta Maurya founded the Maurya Empire.

However, other texts, particularly the Buddhist Mahavamsa Tika and Jain Parishishtaparvan, record initial unsuccessful attacks on the Nanda capital. Following these setbacks, Chandragupta and Chanakya refined their strategy. They began by campaigning along the Nanda empire's frontier, gradually conquering various territories and establishing garrisons as they advanced towards the capital. Finally, they besieged Pataliputra, where Dhana Nanda was defeated. In contrast to Buddhist accounts that suggest an easy victory, Hindu and Jain texts portray the campaign as fiercely fought, owing to the Nanda dynasty's powerful and well-trained army. These legends state that the Nanda emperor was defeated, deposed, and, by some accounts, exiled, while Buddhist accounts claim he was killed.

The historically reliable details of Chandragupta's campaign into Pataliputra are scarce, and the legends, written centuries later, are inconsistent. While his victory and ascension to the throne are usually dated to circa 322-319 BCE, alternative chronologies place these events between circa 311 and 305 BCE. The Greek writer Plutarch, in his Life of Alexander, asserted that the Nanda king was so unpopular that Alexander could have easily conquered India if he had tried. Buddhist texts like Milindapanha claim that Chandragupta, with Chanakya's guidance, conquered Magadha to restore dharma. Some legends also narrate that the defeated Nanda emperor was permitted to leave Pataliputra alive with his family's possessions, and Jain sources even attest that his daughter married Chandragupta.

4.4. Founding the Maurya Empire

The defeat of the Nanda dynasty and the subsequent capture of Pataliputra by Chandragupta Maurya marked the definitive establishment of the Maurya Empire. This event was of immense historical significance, as it ended the long-standing rule of the Nandas and ushered in a new era of centralized imperial power in ancient India. Under Chandragupta, the Maurya Empire became the first large-scale, unified Indian empire, laying the groundwork for a vast domain that would eventually encompass much of the Indian subcontinent and extend into parts of Afghanistan. This foundational act reshaped the political map of India, setting the stage for future expansion and consolidation under his successors.

5. Expansion and Consolidation of the Empire

After establishing the Maurya Empire, Chandragupta Maurya continued to expand and stabilize his dominion through both military campaigns and diplomatic maneuvers, notably with the Seleucid Empire.

5.1. Alliance with Seleucus I Nicator

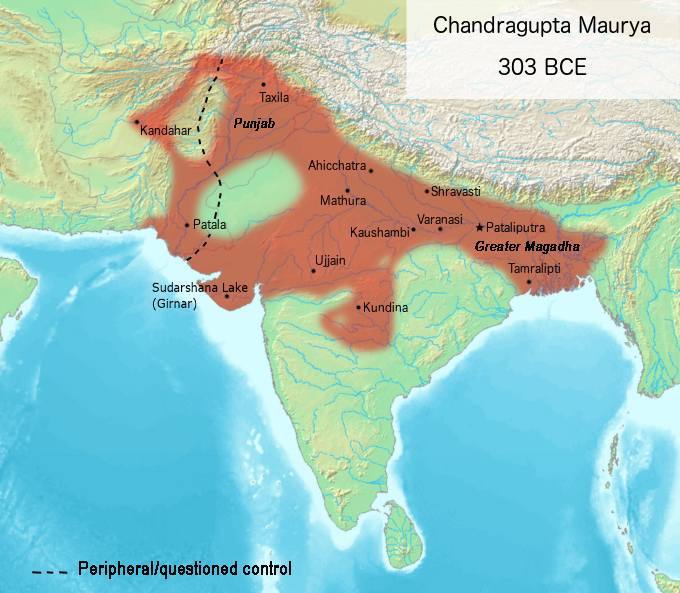

Following Alexander the Great's death, his Macedonian general Seleucus I Nicator established the Seleucid Empire in 312 BCE, with its capital at Babylon, bringing Persia and Bactria under his control. This expansion brought his eastern frontier into contact with Chandragupta Maurya's growing empire. Around 305 to 303 BCE, Seleucus and Chandragupta engaged in a confrontation, with Seleucus aiming to reclaim the former satrapies along the Indus River.

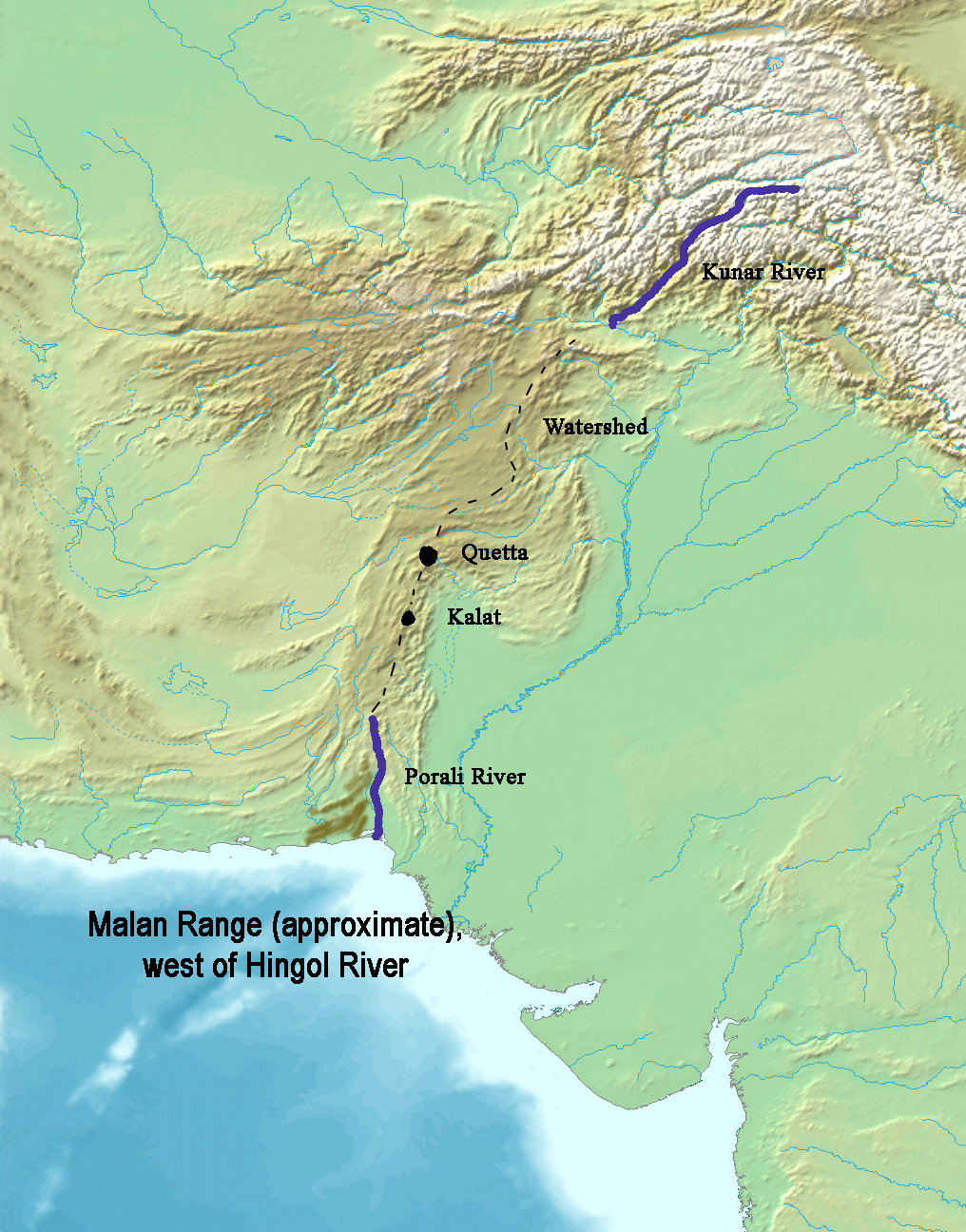

Despite Seleucus's intentions, the conflict concluded with a peace treaty and a dynastic marriage alliance. Under the terms of the treaty, Seleucus I Nicator ceded territories to Chandragupta, including the regions bordering the Indus to the east. These territories included Paropamisadae (Gandhara), Arachosia (Kandahar in modern-day Afghanistan), and Gedrosia (Balochistan). In exchange, Chandragupta provided Seleucus with 500 war elephants, which proved to be a crucial asset in Seleucus's victory at the Battle of Ipsus in 301 BCE, a decisive conflict in the Wars of the Diadochi.

The exact extent of the acquired territories is a subject of scholarly debate. While a modest interpretation limits the expansion to the western Indus Valley, including the coast of eastern Gedrosia up to the Malan mountain range, some scholars also consider the inclusion of Aria (present-day Herat, Afghanistan), though this is often rejected by contemporary scholarship. Recent research also questions the extent of Mauryan control over eastern Afghanistan and the lower Indus Valley, suggesting these may have been areas of maximum contact rather than direct bureaucratic control.

The details of the dynastic marriage are also not fully known. Since extensive sources on Seleucus do not mention an Indian princess, it is generally thought that either Chandragupta himself or his son Bindusara married a Seleucid princess, in accordance with Greek practices for forming dynastic alliances. Conversely, some Indian Puranic sources, like the Pratisarga Parva of the Bhavishya Purana, describe Chandragupta marrying a Greek ("Yavana") princess, daughter of Seleucus. In addition to the treaty, Seleucus dispatched Megasthenes as an ambassador to Chandragupta's court in Pataliputra for four years, and later, Antiochos sent Deimakos to Bindusara's court.

5.2. Control of Western and Southern India

Chandragupta Maurya's control over present-day Gujarat in western India is substantiated by archaeological evidence. The Junagadh rock inscription of Rudradaman, dated to approximately 150 CE, located in Gujarat, states that the Sudarshana Lake in the region was commissioned during Chandragupta's rule through his governor Vaishya Pushyagupta. This inscription also notes that conduits were added during the reign of his grandson Ashoka through Tushaspha. This corroborates Mauryan control over the region and suggests that Chandragupta's empire extended to the Malwa region in Central India, strategically situated between Gujarat and Pataliputra.

There is uncertainty regarding Chandragupta's conquests in the Deccan region of Southern India. By the time of his grandson Ashoka's ascension around 268 BCE, the empire extended into present-day Karnataka in the south, leading to speculation that these southern conquests could be attributed to either Chandragupta or his son Bindusara. Historian Radha Kumud Mookerji argues for Chandragupta's southern expansion, citing Plutarch's statement that "Androcottus [...] with an army of 600,000 men overran and subdued all India." Mookerji also refers to the Jain tradition of Chandragupta's retirement in Shravanabelagola, Karnataka, which, if historically accurate, would imply his prior conquest of the south.

However, the Digambara Jain accounts are debated. The stories of his conversion to Jainism and retirement at Shravanabelagola with Bhadrabāhu only appear in Digambara Jain sources that developed after 600 CE. Some scholars suggest these accounts might confuse Chandragupta Maurya with his great-great-grandson, Samprati, who was also named Chandragupta. Furthermore, Svetambara Jain texts contradict these narratives, stating that Bhadrabahu remained near the Nepalese foothills of the Himalayas in the 3rd century BCE and did not travel south with Chandragupta Maurya. The Digambara legends may also have mistakenly identified Prabhacandra, an important Jain monk-scholar who lived centuries after Chandragupta, as the emperor.

Two poetic anthologies from the Tamil Sangam literature corpus-Akananuru and Purananuru-allude to the Nanda rule and the Maurya Empire, mentioning the army and chariots of the Mauryas. However, these poems, dated between the 1st century BCE and 5th century CE, do not explicitly name Chandragupta Maurya. Some interpretations suggest they might refer to a different Moriya dynasty in the Deccan region from the 5th century CE or indicate an alliance between the Maurya Empire and local kingdoms in Karnataka and Andhra Pradesh.

6. Administration and Reforms

Chandragupta Maurya's reign was characterized by a structured administration, significant economic policies, and a remarkable period of infrastructure development, alongside a policy of religious pluralism across his vast empire.

6.1. Governance Structure

After consolidating control over northern India, Chandragupta and Chanakya implemented a series of major economic and political reforms. Chandragupta established a decentralized administration that included various provinces and local governments. He was advised by a mantriparishad, or council of ministers, with Chanakya serving as his chief minister. Although it was once widely believed that Chandragupta directly applied the statecraft and economic policies detailed in the Arthashastra, which was previously attributed to Chanakya, most modern scholars now suggest that the Arthashastra is not of Mauryan origin and contains prescriptions incompatible with Chandragupta's actual reign.

The Maurya administration was highly organized, with the empire structured into territories called janapada. Centers of regional power were fortified with durga (forts), and state operations were funded by a treasury, or kosa. According to Strabo's Geographica, written centuries after Chandragupta's death, the administration included councillors for justice and assessors responsible for collecting taxes on commercial activities and trade goods. His officers ensured law and order in cities, and the crime rate was reportedly low.

Megasthenes, the Greek ambassador to Chandragupta's court, described three parallel administrative structures. One managed the affairs of villages, ensuring irrigation, recording land ownership, monitoring tools supply, enforcing hunting, wood products and forest-related laws, and settling disputes. A second structure handled city affairs, including trade, merchant activity, visit of foreigners, harbors, roads, temples, markets, and industries. They also collected taxes and ensured standardized weights and measures. The third administrative body overlooked the military, its training, its weapons supply, and the needs of the soldiers.

Chanakya was notably concerned with Chandragupta's personal safety and devised elaborate techniques to guard against assassination attempts. Various sources indicate that Chandragupta frequently changed his bedrooms to confuse potential conspirators. He limited his public appearances, leaving the palace only for military expeditions, dispensing justice in his court, offering sacrifices, participating in celebrations, and hunting. During celebrations, he was heavily guarded, and on hunts, he was surrounded by female guards, who were presumed less likely to be involved in coup conspiracies. These stringent security measures likely stemmed from the historical context of the Nanda emperor, who had ascended to power by assassinating his predecessor.

6.2. Economic Policies and Infrastructure Development

Chandragupta's reign and the Maurya Empire were characterized by significant economic prosperity and a strong focus on infrastructure. Ancient epigraphical evidence suggests that Chandragupta, under Chanakya's advice, initiated and completed numerous irrigation reservoirs and networks across the Indian subcontinent. These projects were crucial for ensuring food supplies for both the civilian population and the army, a practice continued by his successors. Regional prosperity in agriculture was a key responsibility of his state officials.

The most substantial evidence of infrastructure development comes from the Junagadh rock inscription of Rudradaman in Gujarat, dated to circa 150 CE. This inscription states that Rudradaman repaired and enlarged the reservoir and irrigation conduit infrastructure originally built by Chandragupta and later enhanced by Ashoka. Chandragupta's empire also fostered the development of mines and manufacturing centers, and established extensive networks for trading goods. His administration significantly expanded "roads suitable for carts," favoring them over narrower tracks, which facilitated trade and commerce across the subcontinent.

Historian Kaushik Roy notes that the Maurya dynasty rulers were "great road builders." Megasthenes is credited with linking this tradition to Chandragupta after the completion of a thousand-mile-long highway connecting Chandragupta's capital, Pataliputra, in Bihar to Taxila in the northwest. Other major strategic road infrastructure attributed to this era radiated from Pataliputra in various directions, connecting it with regions such as Nepal, Kapilavastu, Dehradun, Mirzapur, Odisha, Andhra Pradesh, and Karnataka. This extensive road network boosted trade and commerce, and enabled the rapid and efficient movement of armies.

Chandragupta and Chanakya established weapon manufacturing centers as a state monopoly, while encouraging private parties to operate mines and supply these centers. They viewed economic prosperity as essential for the pursuit of dharma (virtuous life) and adopted a policy that prioritized diplomacy to avoid war, yet continuously prepared the army for defense, embodying principles found in the Arthashastra.

6.3. Arts, Architecture, and Religious Pluralism

Evidence regarding arts and architecture during Chandragupta's reign is primarily drawn from textual sources such as Megasthenes and Kautilya. Monumental pillars and edict inscriptions are largely attributed to his grandson Ashoka. However, the texts imply the existence of flourishing cities, public works, and impressive architecture, though the exact historicity of these descriptions remains a subject of scholarly inquiry.

Archaeological discoveries, such as the Didarganj Yakshi found in 1917 buried near the Ganges, suggest exceptional artisanal accomplishment. This sculpture was dated to the 3rd century BCE by many scholars, aligning with the Maurya period, though later dates, such as the Kushan Empire (1st-4th century CE), have also been proposed. Debates exist on whether the art of Chandragupta Maurya's dynasty was influenced by Greek and West Asian styles following Alexander's campaigns or if it stemmed from an older indigenous Indian tradition. As Frederick Asher notes, there is no single definitive answer, and interpretations remain open.

During Chandragupta's reign and throughout the Maurya Empire, religious pluralism was a prominent feature. Many religions thrived within his realms, with Buddhism, Jainism, and Ajivika gaining prominence alongside other folk traditions. Chandragupta himself sponsored Vedic sacrifices and Brahmanical rituals. Minority religions, including Zoroastrianism and the Greek pantheon, were also respected. This period initiated, under Ashoka, the expansion of Buddhism and the synthesis of Brahmanic and non-Brahmanic religious traditions that later converged in Hinduism.

7. Later Life and Death

The final years of Chandragupta Maurya's rule and the circumstances surrounding his death are subjects of historical debate, with varying accounts from ancient texts and contested legends.

7.1. Jain Accounts of Renunciation and Death

According to Digambara Jain accounts, Chandragupta Maurya abdicated his throne at an early age and became a monk under the Jain spiritual leader Bhadrabāhu in Shravanabelagola, located in present-day southern Karnataka. These accounts suggest that Bhadrabāhu foresaw a 12-year famine, possibly due to the violence and killing associated with Chandragupta Maurya's conquests. Consequently, Bhadrabāhu led a group of Jain monks, including Chandragupta, to south India. The Digambara legend states that Chandragupta lived as an ascetic at Shravanabelagola for several years before peacefully welcoming death by fasting, a Jain religious ritual known as sallekhana. In accordance with this tradition, the hill where Chandragupta is believed to have performed his asceticism is now known as Chandragiri hill, and Digambaras believe that Chandragupta Maurya constructed an ancient temple there, now known as the Chandragupta basadi.

The earliest mention of Chandragupta's ritualistic death appears in Harisena's Brhatkathakosa (931 CE), a Sanskrit collection of stories about Digambara Jains, which details the legend of Bhadrabahu and mentions Chandragupta in its 131st story. However, this story makes no mention of the Maurya Empire and states that his disciple Chandragupta lived in and migrated from Ujjain, a kingdom located approximately 0.6 K mile (1.00 K km) west of Magadha and Pataliputra. This geographical discrepancy has led some scholars to propose that Harisena's Chandragupta may be a different person from a later era.

In contrast, the 12th-century Svetambara Jain legend by Hemachandra presents a different perspective. This version includes stories of Jain monks using invisibility to steal food from imperial storage and the Jain Brahmin Chanakya employing violence and cunning tactics to expand Chandragupta's empire and increase revenues. Hemachandra's text states that for 15 years as emperor, Chandragupta was a follower of "ascetics with the wrong view of religion" and "lusted for women." Chanakya, described as a Jain convert himself, persuaded Chandragupta to convert to Jainism by demonstrating the Jain ascetics' focus on religion and avoidance of women. The legend also mentions Chanakya aiding the premature birth of Bindusara and states that Chandragupta "died in meditation" (possibly sallekhana) and went to heaven. Hemachandra's legend also claims that Chanakya performed sallekhana.

Several Digambara Jain inscriptions from the 7th-15th century in Karnataka refer to Bhadrabahu and a figure named Prabhacandra. Later Digambara tradition identified Prabhacandra as Chandragupta. While some modern scholars have accepted this identification, others, including J. F. Fleet and V. R. Ramachandra Dikshitar, dispute it. Dikshitar argues there is no evidence to support this claim, asserting that Prabhacandra was an important Jain monk-scholar who migrated centuries after Chandragupta, as the emperor. Many late Digambara inscriptions and texts in Karnataka state that the journey to the south began from Ujjain, not Pataliputra, further complicating the narrative.

7.2. Historical Uncertainty of Death

The precise time and circumstances of Chandragupta Maurya's death remain unclear and are a subject of historical dispute due to a lack of definitive evidence from contemporary sources. The powerful and detailed narratives surrounding his renunciation and death by sallekhana are predominantly found in Digambara Jain accounts, which developed significantly after 600 CE.

Scholars like Paul Dundas note that the Svetambara tradition of Jainism disputes these ancient Digambara legends. According to a 5th-century Svetambara text, the Digambara sect itself was founded much later, in the 1st century CE, or 609 years after Mahavira's death. Svetambara texts claim that Bhadrabahu was located near the Nepalese foothills of the Himalayas in the 3rd century BCE and neither moved nor traveled with Chandragupta Maurya to the south; rather, he died near Pataliputra.

Jeffery D. Long suggests that some Digambara versions might confuse Chandragupta Maurya with his great-great-grandson, Samprati Chandragupta, who also renounced and migrated. This confusion could explain the later dating of the legends. Sushma Jansari concludes that "the evidence as it currently stands suggests that the story of Chandragupta's conversion to Jainism and abdication (if, indeed, he did abdicate), his migration southwards and his association (or otherwise) with Bhadrabāhu and the site of Śravaṇa Beḷgoḷa developed after c.600 AD."

Despite these scholarly debates and the problematic nature of some sources, V. R. Ramachandra Dikshitar adopts the hypothesis of Chandragupta's retirement and death in Shravanabelagola as a working theory, given the absence of alternative historical information or evidence about his final years.

8. Legacy and Assessment

Chandragupta Maurya's reign left an indelible mark on Indian history, establishing a template for imperial governance and cultural integration that resonated for centuries. His legacy continues to be assessed from various viewpoints and is honored through modern commemorative activities.

8.1. Historical Significance and Positive Viewpoints

Chandragupta Maurya holds immense historical significance as the first emperor to establish a large, unified Indian empire. His achievements laid the foundational framework for the Maurya Empire, which under his grandson Ashoka, reached its zenith, extending across nearly the entire Indian subcontinent. He is widely regarded as the visionary unifier of India, bringing together disparate kingdoms and regions under a single political entity, a concept often referred to as Akhand Bharat (United India) by Indian nationalists.

Many Indian scholars and nationalists positively appraise his accomplishments, highlighting his strategic brilliance, administrative reforms, and the economic prosperity he ushered in. His symbolic status as a foundational figure in Indian history is deeply embedded in the national consciousness, representing the ideal of a strong and unified nation.

8.2. Criticisms and Controversies

Despite widespread admiration, Chandragupta's rule has also faced criticisms and remains a subject of historical controversies. Some Greek sources, particularly Justin, describe his post-liberation regime as "oppressive," implying that he imposed his own form of servitude on the people he had freed from foreign domination. This perspective suggests a more authoritarian aspect to his rule than often highlighted in Indian narratives.

Another significant controversy revolves around the direct application of the Arthashastra during his reign. While historically attributed to his minister Chanakya and often associated with Mauryan governance, contemporary scholarship widely holds that the text was composed centuries after Chandragupta's time (1st to 3rd century CE). Therefore, the extent to which the detailed, sometimes ruthless, statecraft principles outlined in the Arthashastra were actually implemented by Chandragupta remains debated. Some scholars argue that its prescriptions are incompatible with the realities of his decentralized administration and the prevailing levels of technology and infrastructure during his time.

8.3. Commemoration

Contemporary activities continue to honor Chandragupta Maurya's historical significance. A prominent memorial dedicated to him exists on Chandragiri hill in Shravanabelagola, Karnataka. This site is particularly significant in Jain tradition, believed to be where he spent his last days as an ascetic. The Indian Postal Service issued a commemorative postage stamp honoring Chandragupta Maurya in 2001, recognizing his pivotal role in Indian history and his symbolic status as a national unifier.

9. In Popular Culture

Chandragupta Maurya's life and reign have been a recurring subject in various forms of modern popular culture, reinterpreted in dramas, films, novels, and video games across different countries.

- Mudrarakshasa ("The Signet Ring of Rakshasa"), a political drama in Sanskrit composed between 300 CE and 700 CE, fictionalizes the conquest of Chandragupta.

- D. L. Ray wrote a Bengali drama titled Chandragupta, loosely based on the Puranas and Greek historical accounts.

- The novel The Courtesan and the Sadhu by Dr. Mysore N. Prakash focuses on Chanakya's role in the formation of the Maurya Empire.

- Several Indian films have depicted his life, including:

- Chandragupta (1920), a silent film.

- Chandragupta (1934), directed by Abdur Rashid Kardar.

- Samrat Chandragupta (1945) by Jayant Desai.

- Samrat Chandragupt (1958), a remake of the 1945 film, starring Bharat Bhushan.

- Chanakya Chandragupta (1977), a Telugu-language film.

- Chandraguptha Chanakya, a Tamil-language historical drama film.

- He has been the subject of multiple television series:

- Chanakya (1991), which chronicles the life and times of Chanakya, based on the play Mudrarakshasa.

- Chandragupta Maurya (2011) telecast on Imagine TV.

- Chandra Nandini (2016), a fictionalized romance saga.

- Chandragupta Maurya (2018), portraying his life.

- In video games, Chandragupta is a playable leader for the Indian civilization in Civilization VI (2016).

- The Japanese stage play and anime Nobunaga the Fool features a character named Chandragupta, inspired by the emperor.

- In the 2001 Bollywood film Aśoka, directed by Santosh Sivan, Bollywood director and producer Umesh Mehra played the role of Chandragupta Maurya.