1. Early Life and Background

Bruce Lee's early life was marked by his unique origins, influential family connections, and a formative period spent between Hong Kong and the United States, which shaped his diverse perspective on life and martial arts.

1.1. Birth and Family

Bruce Lee was born Lee Jun-fan on November 27, 1940, in Chinatown, San Francisco, California, United States. His birth in the U.S. granted him American citizenship under the principle of jus soli. He was born in the hour and year of the Dragon according to the Chinese zodiac, which is traditionally considered a powerful and auspicious sign.

His father, Lee Hoi-chuen, was a renowned Cantonese opera singer and film actor based in Hong Kong. At the time of Bruce's birth, his parents were on a year-long international opera tour in the United States. His mother, Grace Ho (何愛瑜Chinese), was born in Shanghai and was of Eurasian ancestry. Her background was complex: she was the adopted daughter of Ho Kom-tong (何甘棠Chinese), a notable Hong Kong businessman and philanthropist, and the half-niece of Sir Robert Ho-tung, the Eurasian patriarch of the influential Ho-tung clan. Ho Kom-tong's father, Charles Maurice Bosman, was a Dutch Jewish businessman from Rotterdam who served as the Dutch consul to Hong Kong. He had a Chinese concubine, Sze Tai, with whom he had six children, including Ho Kom-tong. Ho Kom-tong himself had a wife, 13 concubines, and a British mistress who was Grace Ho's biological mother. This mixed heritage, including Chinese, English, and Dutch Jewish roots, made Bruce Lee not entirely of Chinese descent.

Bruce was the fourth of five children. His elder siblings were Phoebe Lee (李秋源Chinese), Agnes Lee (李秋鳳Chinese), and Peter Lee (李忠琛Chinese). His younger brother was Robert Lee (李振輝Chinese). Due to his mother's superstitious nature, she initially named him Sai-fon (細鳳Chinese), a feminine name meaning "small phoenix". The English name "Bruce" is believed to have been given by the attending physician at the hospital, Dr. Mary Glover. His birth name Lee Jun-fan (李振藩Chinese) was given by his mother, meaning "return again," as she felt he would return to the United States when he came of age. The original Chinese character for Jun (震Chinese) in his name was later changed to the homonym 振Chinese to avoid naming taboos, as it was identical to part of his grandfather's name, Lee Jun-biu (李震彪Chinese).

1.2. Childhood and Education in Hong Kong

When Bruce was four months old, in April 1941, the Lee family returned to British Hong Kong. Soon after, Hong Kong was attacked by Japan in December 1941, leading to the Japanese occupation for the next four years. Despite these hardships, the Lee family, due to Grace Ho's wealthy and powerful clan, grew up in an affluent and privileged environment. However, the neighborhood where Lee lived, 218 Nathan Road, Kowloon, became overcrowded and prone to gang rivalries due to an influx of refugees from Communist China.

Bruce Lee was introduced to the Hong Kong film industry at a very young age through his father's career. He had his first role as a baby carried onto the stage in the 1941 Cantonese film Golden Gate Girl. He adopted the Chinese stage name 李小龍Chinese, meaning "Lee the Little Dragon," a nod to his birth year and hour. By the age of 18, he had appeared in 20 films, including his first leading role at age nine in The Kid (1950), co-starring with his father.

His early education included attending Tak Sun School (德信學校Chinese) and then the primary division of the Catholic La Salle College at age 12. In 1956, due to poor academic performance and conduct, he was transferred to St. Francis Xavier's College. He was mentored by Brother Edward Muss, a Bavarian-born teacher and coach of the school's boxing team.

Lee's childhood was also marked by frequent street fighting. He often engaged in fights with British children due to his resentment of their condescending attitude towards the Chinese. These experiences, including neighborhood and rooftop fights, fueled his interest in martial arts. He combined different techniques from various martial arts schools into his own hybrid style. In 1958, he won the Hong Kong schools boxing tournament, knocking out the previous champion, Gary Elms, in the final. That same year, he also won Hong Kong's Crown Colony Cha-Cha Championship, demonstrating another talent.

1.3. Move to the United States and Education

In his late teens, Lee's street fights became more frequent and serious, including an incident where he badly beat the son of a feared triad family, knocking out one of his teeth. This led to a police complaint, and his mother had to sign a document taking full responsibility for his actions. Concerned for his safety and future, his parents decided to send him to the United States to claim his U.S. citizenship.

In April 1959, Lee traveled to San Francisco with just 100 USD and stayed with his elder sister, Agnes Lee, who was living with family friends. After several months, he moved to Seattle in 1959 to continue his high school education. There, he worked as a live-in waiter at Ruby Chow's restaurant, whose husband was a co-worker and friend of Lee's father. His elder brother, Peter Lee, briefly joined him in Seattle before moving to Minnesota for college.

Lee completed his high school education and received his diploma from Edison Technical School (now Seattle Central Community College) on Capitol Hill. In March 1961, he enrolled at the University of Washington. While many believed his major was philosophy, university records indicate his official major was drama. However, he did take classes in psychology and philosophy, which became core interests for him throughout his life. During his time at the university, he socialized with wealthy young people but lived in relative poverty, working as a dishwasher in a Chinese restaurant.

2. Martial Arts Career

Bruce Lee's martial arts journey was a lifelong pursuit of self-expression and efficiency, culminating in the creation of Jeet Kune Do, a philosophy that revolutionized combat sports and influenced countless practitioners worldwide.

2.1. Introduction to Martial Arts

Lee's first introduction to martial arts came through his father, Lee Hoi-chuen, from whom he learned the fundamentals of Wu-style tai chi. As a teenager in Hong Kong, his involvement in gang conflicts and frequent street fightings further spurred his interest in formal training. He often participated in bare-knuckle fights on Hong Kong's rooftops, a common practice among rival martial arts schools to avoid colonial authorities. These experiences instilled in him a practical, no-nonsense approach to combat.

2.2. Wing Chun and Key Teachers

The most significant influence on Lee's early martial arts development was his study of Wing Chun. At 16, in late 1956 or 1957, he began training under the renowned Grandmaster Ip Man. Initially, Lee faced rejection from some students due to his mixed Eurasian ancestry, as there was a long-standing rule in Chinese martial arts against teaching foreigners. However, his friend William Cheung advocated for him, and Lee was accepted.

Ip Man's regular classes typically involved form practice, chi sao (sticking hands) drills, wooden dummy techniques, and free sparring. Lee showed exceptional interest and diligently continued to train privately with Ip Man, William Cheung, and Wong Shun-leung, who was his primary instructor for beginners. Wong Shun-leung, a senior student of Ip Man, played a crucial role in shaping Lee's Wing Chun foundation, emphasizing practicality and directness.

2.3. Boxing, Street Fighting, and Other Influences

Lee's martial arts development was eclectic, drawing from various disciplines and real-world combat experiences. Between 1956 and 1958, he trained in boxing under Brother Edward, the coach of the St. Francis Xavier's College boxing team, ultimately winning the Hong Kong schools boxing tournament in 1958.

His frequent engagement in street fighting in Hong Kong, particularly the rooftop fights against rival martial arts schools, taught him the raw realities of combat and the limitations of rigid, formalized techniques. These experiences pushed him to seek more practical and adaptable methods.

After moving to the United States, Lee was heavily influenced by the footwork and techniques of heavyweight boxing champion Muhammad Ali. He studied Ali's movements and incorporated them into his own style in the 1960s. He also became interested in other combat forms, training with judo practitioners like Fred Sato, Jesse Glover, Taky Kimura, Hayward Nishioka, and Wally Jay, as well as professional wrestler Gene LeBell. Lee exchanged knowledge with LeBell, learning grappling techniques in return for striking instruction. He also learned grappling moves from hapkido master Ji Han-jae. Furthermore, Lee was influenced by the training routine of The Great Gama, an Indian/Pakistani pehlwani wrestling champion, whose exercises he integrated into his regimen.

2.4. Development of Jeet Kune Do

The controversial private match with Wong Jack-man in 1964 significantly influenced Lee's philosophy. He concluded that the fight had lasted too long and that his traditional Wing Chun techniques were too rigid for chaotic street fighting. This realization prompted him to develop a new system emphasizing "practicality, flexibility, speed, and efficiency."

This new hybrid system, which he initially called Jun Fan Gung Fu (literally "Bruce Lee's Kung Fu"), evolved into a philosophy and martial art he named Jeet Kune Do (JKD), meaning "Way of the Intercepting Fist" in 截拳道Cantoneseyue. Originating in 1967, JKD incorporated footwork from boxing, kicks from kung fu, and techniques from fencing. Lee famously emphasized "the style of no style," advocating for the removal of formalized approaches and limitations. He later expressed regret for the name "Jeet Kune Do" itself, as it implied specific parameters, whereas his art aimed to exist beyond such boundaries. The emblem of Jeet Kune Do, a registered trademark of the Bruce Lee Estate, features the Taijitu symbol surrounded by Chinese characters that read: "Using no way as way" and "Having no limitation as limitation," with arrows representing the endless interaction between yang and yin.

2.5. Fitness and Nutrition

Standing at 5.6 ft (1.72 m) and weighing 141 lb (64 kg), Lee was renowned for his exceptional physical fitness and vigor, achieved through a dedicated and evolving regimen. After his match with Wong Jack-man in 1965, he intensified his training, believing that many martial artists neglected physical conditioning. His approach to fitness was holistic, encompassing muscular strength, muscular endurance, cardiovascular endurance, and flexibility.

He incorporated traditional bodybuilding techniques to build muscle mass, but carefully avoided excessive bulk that could hinder speed or flexibility. His workouts included weight training (e.g., biceps curls with 71 lb (32 kg) to 79 lb (36 kg) per arm), running (2.2 mile (3.6 km) to 6.0 mile (9.6 km) three times a week, often with fartlek intervals), jump rope (30 minutes on other days, sometimes on one leg for balance), and cycling (45 minutes on an exercise bike). He also performed circuit training with 8-12 exercises, each lasting 30-60 seconds without rest, to avoid plateaus. Lee believed the abdominal muscles were crucial for a martial artist and frequently performed continuous sit-ups and other core exercises throughout the day, even while watching television. He also practiced meditation as the first action on his schedule.

Lee also paid meticulous attention to his nutrition. Soon after moving to the United States, he developed an interest in health foods, high-protein drinks, and vitamin and mineral supplements. He viewed the body as a high-performance automobile, requiring optimal fuel. He avoided baked goods and refined flour, considering them "empty calories," and favored Asian cuisine with its combination of vegetables, rice, and fish. He disliked dairy products and used powdered milk as a substitute.

2.6. Demonstrations and Competitions

Lee actively showcased his martial arts abilities at various events, most notably the Long Beach International Karate Championships. He made appearances in 1964 and 1968, with higher-quality video footage available from the latter.

At these demonstrations, Lee performed impressive feats such as:

- Two-finger push-ups**: Executing repetitions using only his thumb and index finger of one hand, with his feet approximately shoulder-width apart.

- One-inch punch**: Standing upright, with his right foot forward and knees slightly bent, his right fist positioned about 1 in from a stationary partner's chest. Without retracting his arm, he delivered a forceful punch that sent volunteers like Bob Baker backward into a chair and then to the floor. Baker famously recalled, "I told Bruce not to do this type of demonstration again. When he punched me that last time, I had to stay home from work because the pain in my chest was unbearable."

- Blindfolded chi sao drills**: Demonstrating his "sticking hands" techniques while blindfolded, probing for weaknesses and scoring with punches and takedowns against an opponent.

- Full-contact sparring**: Engaging in bouts against opponents wearing leather headgear, showcasing his Jeet Kune Do principles of economical motion, Ali-inspired footwork, counter-attacking with backfists and straight punches, and using stop-hit side kicks, sweeps, and head kicks.

At the 1964 championships, Lee first met Taekwondo master Jhoon Rhee. They developed a friendship, mutually benefiting from their martial arts exchange. Rhee taught Lee the side kick in detail, while Lee taught Rhee the "non-telegraphic" punch, a rapid punch designed to finish execution before an opponent can react. Rhee later incorporated this "accupunch" into American Taekwondo.

Lee also used these platforms to publicly criticize classical karate and kung fu styles, arguing for the modernization of martial arts. This controversial stance convinced some while offending more traditional practitioners.

2.7. The Match with Wong Jack-man

In 1964, Lee had a controversial private match with Wong Jack-man in Oakland, California. Wong Jack-man was a direct student of Ma Kin Fung, known for his mastery of Xingyiquan, Northern Shaolin, and tai chi.

According to Lee and his wife, Linda Lee Cadwell, the Chinese martial arts community issued an ultimatum to Lee: stop teaching non-Chinese people. When he refused, he was challenged to a combat match with Wong. The agreement was that if Lee lost, he would have to shut down his school, but if he won, he would be free to teach anyone, regardless of ethnicity. Wong, however, denied this, stating that he challenged Lee after Lee boasted during a demonstration that he could beat anyone in San Francisco, and that he himself did not discriminate against non-Chinese students. Lee reportedly commented, "That paper had all the names of the sifu from Chinatown, but they don't scare me."

Witnesses to the match included Linda Cadwell, James Yimm Lee (Lee's associate), and William Chen, a tai chi teacher. Accounts of the fight vary significantly:

- Wong Jack-man and William Chen's account**: They stated the fight lasted an unusually long 20-25 minutes. Wong claimed that Lee aggressively attacked him with intent to kill, even thrusting his hand as a spear aimed at Wong's eyes after appearing to accept a traditional handshake. Wong asserted he refrained from striking Lee with killing force to avoid a prison sentence, and that the fight ended due to Lee's "unusually winded" condition, not a decisive blow.

- Bruce Lee, Linda Lee Cadwell, and James Yimm Lee's account**: They maintained the fight lasted a mere three minutes, with a decisive victory for Lee. Cadwell recalled, "The fight ensued, it was a no-holds-barred fight, it took three minutes. Bruce got this guy down to the ground and said 'Do you give up?' and the man said he gave up."

After the bout, Lee gave an interview claiming he had defeated an unnamed challenger, which Wong took as a direct reference to him. Wong then published his account in the Pacific Weekly, a Chinese-language newspaper in San Francisco, inviting Lee to a public rematch. Lee did not respond, despite his reputation for reacting to provocations.

Regardless of the differing accounts, Lee was reportedly unhappy with the outcome, feeling he had failed to live up to his potential using his Wing Chun techniques. This experience became a pivotal moment, leading him to pursue further innovations in his personal martial arts style, ultimately culminating in Jeet Kune Do.

2.8. Key Students

Bruce Lee attracted a diverse group of students, many of whom became prominent figures in martial arts and Hollywood, helping to preserve and propagate his teachings. His early student group in Seattle was notably racially diverse for Chinese martial arts at the time.

Some of his most prominent students and disciples included:

- Taky Kimura: Lee's first Assistant Instructor, who continued to teach his art and philosophy in Seattle after Lee's death. He was a Japanese-American martial artist who helped establish Lee's first kwoon (martial arts school) in Seattle.

- Jesse Glover: A judo practitioner and Lee's first student in Seattle, who continued to teach some of Lee's early techniques.

- James Yimm Lee: A well-known Chinese martial artist in Oakland, California, who was twenty years Lee's senior. Together, they founded the second Jun Fan martial arts studio in Oakland. James Lee was also instrumental in introducing Bruce Lee to Ed Parker, the organizer of the Long Beach International Karate Championships.

- Dan Inosanto: A Filipino-American martial artist who became one of Lee's three personally certified 3rd rank instructors. He continued to teach Jeet Kune Do and trained Lee's son, Brandon Lee, after Bruce's death.

- Ted Wong: A close student and sparring partner of Lee, who played a significant role in preserving and promoting Jeet Kune Do after Lee's passing.

- Chuck Norris: A karate champion and actor who became a friend and training partner of Lee, famously co-starring in The Way of the Dragon.

- Kareem Abdul-Jabbar: The legendary basketball star, who was also a student and friend of Lee, appearing in his unfinished film Game of Death.

- James Coburn: A Hollywood actor and martial arts student who was a close friend of Lee and worked with him on the script for The Silent Flute. He was one of Lee's pallbearers.

- Steve McQueen: A famous actor and friend of Lee, who also served as a pallbearer.

- Sharon Tate: An actress who studied martial arts with Lee in preparation for her film roles.

- Roman Polański: A film director who studied martial arts with Lee.

- Stirling Silliphant: A Hollywood screenwriter and martial arts student who collaborated with Lee on several projects, including The Silent Flute, Marlowe, and Longstreet.

- Joe Lewis: An American karate champion who was offered a role in The Way of the Dragon and was influenced by Lee's approach to full-contact fighting.

- Jhoon Rhee: A Taekwondo master who exchanged techniques with Lee, learning the "accupunch" from him.

3. Acting Career

Bruce Lee's acting career evolved from a child star in Hong Kong to an international martial arts icon, breaking barriers and revolutionizing the portrayal of Asians in cinema.

3.1. Early Acting Career in Hong Kong

Bruce Lee's acting career began at a remarkably young age, influenced by his father, Lee Hoi-chuen, a prominent Cantonese opera and film star. At just three months old, he made his debut as a baby carried onto the stage in the 1941 Cantonese film Golden Gate Girl. He quickly became a child actor, appearing in numerous films throughout his childhood in Hong Kong. By the time he was 18, he had already featured in 20 films. His first leading role came at age nine in The Kid (1950), where he co-starred with his father. During this period, he adopted the Chinese stage name 李小龍Chinese (Lee Siu-lung), meaning "Lee the Little Dragon," a moniker that would become synonymous with his legendary status.

3.2. American Television and Film Roles

After moving to the United States in 1959, Lee initially focused on his education and martial arts teaching, stepping away from acting. However, a martial arts exhibition at the 1964 Long Beach International Karate Championships caught the attention of television producer William Dozier. Dozier was impressed by Lee's lightning-fast movements and offered him an audition for a pilot tentatively titled "Number One Son," about Lee Chan, the son of Charlie Chan. While that show never materialized, Dozier saw potential in Lee.

From 1966 to 1967, Lee gained his first significant exposure to American audiences by playing Kato alongside Van Williams in The Green Hornet TV series. The show ran for one season (26 episodes). Initially, the director wanted Lee to fight in a typical American style, but Lee insisted on using his martial arts expertise. His movements were so fast that they couldn't be captured on film, requiring him to slow them down for the cameras. The Green Hornet introduced Asian-style martial arts to mainstream American television and garnered a significant following. Lee and Williams also appeared as their characters in three crossover episodes of Batman, another William Dozier production. After The Green Hornet was canceled, Lee thanked Dozier for launching "my career in show business."

In 1969, Lee made a brief but impactful appearance in the film Marlowe, penned by his student Stirling Silliphant. He played Winslow Wong, a hoodlum who uses his martial arts abilities to intimidate private detective Philip Marlowe, played by James Garner. That same year, he was credited as the karate advisor for The Wrecking Crew, a spy-fi comedy starring Dean Martin, and also acted in episodes of Here Come the Brides and Blondie.

In 1970, Lee was responsible for the fight choreography of A Walk in the Spring Rain, starring Ingrid Bergman and Anthony Quinn, also written by Silliphant. In 1971, he appeared in four episodes of the television series Longstreet, playing Li Tsung, the martial arts instructor to the title character. Important aspects of Lee's martial arts philosophy were integrated into the script, reflecting his desire to share his ideas through media.

Lee also pitched his own television series concept in 1971, tentatively titled The Warrior, which he envisioned as a Western. Discussions were confirmed by Warner Bros., but the project faced challenges. According to his wife, Linda Lee Cadwell, Lee's concept was retooled and renamed Kung Fu, but Warner Bros. gave Lee no credit. Warner Bros. stated they had been developing a similar concept since 1969. Lee was reportedly not cast due to his thick accent and ethnicity, with producer Fred Weintraub attributing it to the latter. The role of the Shaolin monk was ultimately given to David Carradine, a non-martial artist. Lee expressed understanding of Warner Bros.' business perspective, acknowledging the risk of casting an Asian lead for American audiences.

3.3. Breakthrough in Hong Kong Cinema

Dissatisfied with the limited supporting roles offered in the U.S., Lee returned to Hong Kong. Unbeknownst to him, The Green Hornet had been a massive success there, unofficially dubbed "The Kato Show," and he was surprised to be recognized as a star. After negotiations with both Shaw Brothers Studio and Golden Harvest, Lee signed a contract with Golden Harvest.

Lee landed his first leading film role in The Big Boss (1971), which became an enormous box-office success across Asia, catapulting him to stardom. This film, made on a budget of 100.00 K USD, grossed over 3.50 M USD in Hong Kong alone within three weeks and nearly 50.00 M USD worldwide, breaking previous box office records, including The Sound of Music.

He followed this success with Fist of Fury (1972), which broke the box office records set by The Big Boss. This film, also made for 100.00 K USD, grossed an estimated 100.00 M USD worldwide, further cementing his status.

Having completed his initial two-film contract, Lee negotiated a new deal and formed his own company, Concord Production Inc. (協和電影公司Chinese), with Raymond Chow. For his third film, The Way of the Dragon (1972), he was given complete creative control, serving as writer, director, star, and choreographer of the fight scenes. This film introduced American karate champion Chuck Norris to moviegoers as Lee's opponent in an iconic showdown characterized as "one of the best fight scenes in martial arts and film history." The Way of the Dragon grossed an estimated 130.00 M USD worldwide, becoming the highest-grossing film in Hong Kong history at the time.

These commercially successful Hong Kong films elevated martial arts cinema to a new level of popularity and acclaim, sparking a surge of Western interest in Chinese martial arts. Lee's direction and the tone of his films, particularly their fight choreography and diversification, dramatically influenced and changed martial arts and martial arts films worldwide. Kung fu films, with their more realistic choreography and focus on real-world conflicts, began to displace the wuxia film genre, and male leads transitioned from chivalrous heroes to embodying a new notion of masculinity.

3.4. International Stardom with Enter the Dragon

From August to October 1972, Lee began work on his fourth Golden Harvest film, Game of Death. He filmed over 100 minutes of footage, including fight sequences with 7.2 ft (2.18 m) American basketball star Kareem Abdul-Jabbar, a former student. Production halted in November 1972 when Warner Bros. offered Lee the opportunity to star in Enter the Dragon, the first film to be jointly produced by Concord Production Inc., Golden Harvest, and Warner Bros.

Filming for Enter the Dragon began in Hong Kong in February 1973 and was completed in April 1973. One month into filming, another company, Starseas Motion Pictures, promoted Lee as a leading actor in Fist of Unicorn, though he had only agreed to choreograph its fight sequences as a favor to his friend Unicorn Chan. Lee planned to sue the company but maintained his friendship with Chan. Tragically, only a few months after completing Enter the Dragon, and just six days before its July 26, 1973, release, Lee died.

Enter the Dragon went on to become one of the year's highest-grossing films and cemented Lee's status as a global martial arts legend. Made for 850.00 K USD in 1973 (equivalent to 4.00 M USD in 2007 inflation-adjusted terms), the film is estimated to have grossed over 400.00 M USD worldwide, equivalent to over 2.00 B USD adjusted for inflation as of 2022. The film sparked a brief martial arts fad, influencing popular culture, including songs like "Kung Fu Fighting" and various TV shows.

3.5. Posthumous Works and Legacy in Film

After Lee's death, his unfinished film Game of Death was revived by its director, Robert Clouse, and Golden Harvest. Lee had shot over 100 minutes of footage, including outtakes, before production stopped for Enter the Dragon. This footage featured fights with Abdul-Jabbar, Hapkido master Ji Han-jae, and another of Lee's students, Dan Inosanto, culminating in Lee's character, Hai Tien, clad in a yellow tracksuit, taking on challengers in a five-level pagoda.

In a controversial move, Robert Clouse completed the film using a Lee look-alike (Kim Tai Chung, with Yuen Biao as a stunt double) and archive footage of Lee from his other films, integrating them into a new storyline and cast. The cobbled-together film, released in 1978, contained only about fifteen minutes of actual footage of Lee. The unused footage Lee had filmed was later recovered 22 years later and included in the documentary Bruce Lee: A Warrior's Journey.

Other unproduced works included a film tentatively titled Southern Fist/Northern Leg, which shared similarities with The Silent Flute (later released as Circle of Iron in 1978, starring David Carradine). Another script was titled Green Bamboo Warrior, set in San Francisco and planned to co-star Bolo Yeung. Photoshoot costume tests were organized for some of these planned film projects.

Lee's impact on film continued posthumously. In 2015, Perfect Storm Entertainment and Bruce Lee's daughter, Shannon Lee, announced that the series The Warrior, based on Lee's original concept, would be produced and air on Cinemax. Filmmaker Justin Lin was chosen to direct, with production beginning in October 2017 in Cape Town, South Africa. The series was renewed for a second season in April 2019. In March 2021, producer Jason Kothari acquired the rights to The Silent Flute to develop it into a miniseries, with John Fusco as screenwriter and executive producer. In November 2022, it was announced that Taiwanese filmmaker Ang Lee would direct a biopic on Bruce Lee, with his son Mason Lee cast in the starring role, and Shannon Lee producing.

4. Philosophy and Writings

Beyond his physical prowess, Bruce Lee was a profound thinker whose philosophical insights deeply influenced his martial arts and life.

4.1. Philosophical Ideas and Influences

While primarily known as a martial artist, Lee was a dedicated student of drama and both Eastern and Western philosophy, a pursuit he began at the University of Washington. He was exceptionally well-read, possessing an extensive library rich with martial arts and philosophical texts. His writings on martial arts and fighting philosophy are celebrated for their profound philosophical assertions, extending beyond martial arts circles. His eclectic philosophy often mirrored his fighting beliefs, though he was quick to clarify that his martial arts served as a metaphor for these broader teachings.

Lee believed that all knowledge ultimately leads to self-knowledge, and he identified martial arts as his chosen method of self-expression. His philosophical influences were diverse, including Taoism and Buddhism. He was particularly interested in the Indian mystic Jiddu Krishnamurti. Lee's philosophy stood in stark contrast to the conservative worldview advocated by Confucianism. John Little, a notable editor of Lee's works, stated that Lee was an atheist. When asked about his religious affiliation in 1972, Lee replied, "None whatsoever." When questioned about his belief in God, he stated, "To be perfectly frank, I really do not."

In his personal notebooks, Lee cited and commented on passages from prominent Western philosophers such as Plato, David Hume, René Descartes, and Thomas Aquinas. From Eastern thought, he drew inspiration from figures like Lao-tzu, Chuang-tzu, Miyamoto Musashi, and Alan Watts. This rich intellectual foundation underpinned his unique perspective on life and martial arts as interconnected concepts, emphasizing adaptability, fluidity, and the pursuit of truth through direct experience.

4.2. Writings and Poetry

Lee's intellectual contributions extended to his written works, which provided a deeper understanding of his philosophical and martial arts principles. His seminal works include:

- Chinese Gung-Fu: The Philosophical Art of Self Defense (1963): This was Lee's first book, published during his lifetime.

- Tao of Jeet Kune Do (published posthumously in 1973): This work is a compilation of Lee's notes, thoughts, and philosophical insights on his martial art, Jeet Kune Do. It delves into the principles of fluidity, adaptability, and "the style of no style," reflecting his core philosophy.

- Bruce Lee's Fighting Method (published posthumously in 1978): This series of books, compiled from his extensive notes and training methods, systematically outlines his approach to physical conditioning, striking, grappling, and self-defense techniques.

Beyond his martial arts treatises, Lee also wrote poetry that offered a glimpse into his emotional and introspective side. His daughter, Shannon Lee, noted that "He did write poetry; he was really the consummate artist." His poetic works, originally handwritten, were later edited and published, with John Little serving as a major editor. His wife, Linda Lee Cadwell, shared his notes and poems, observing that "Lee's poems are, by American standards, rather dark-reflecting the deeper, less exposed recesses of the human psyche."

Most of Lee's poems are categorized as anti-poetry or delve into paradoxical themes. The mood in his poetry often parallels that of poets like Robert Frost, expressing himself through darker works. The paradox drawn from the Yin and Yang symbol, central to his martial arts philosophy, was also integrated into his poetry. The free verse form of Lee's poetry directly reflects his famous quote, "Be formless... shapeless, like water," emphasizing fluidity and adaptability in both life and art.

5. Personal Life

Bruce Lee's personal life was marked by significant relationships and experiences that shaped his journey, from his family connections to his friendships and the challenges he faced.

5.1. Family

Bruce Lee's father, Lee Hoi-chuen, was a leading Cantonese opera and film actor. He had been touring the United States for many years before Bruce's birth. After Bruce's birth, Lee Hoi-chuen returned to Hong Kong, where the family lived under Japanese occupation during World War II. After the war, his father resumed his acting career and became even more popular during Hong Kong's rebuilding years.

Lee's mother, Grace Ho, hailed from one of Hong Kong's wealthiest and most powerful clans, the Ho-tungs. As the half-niece of Sir Robert Ho-tung, the Eurasian patriarch of the clan, Grace Ho ensured that young Bruce grew up in an affluent and privileged environment. Despite this, the neighborhood where Lee was raised became overcrowded and dangerous due to an influx of refugees, leading to gang rivalries. Bruce was the fourth of five children, with siblings Phoebe Lee (李秋源Chinese), Agnes Lee (李秋鳳Chinese), Peter Lee (李忠琛Chinese), and Robert Lee (李振輝Chinese). His younger brother, Robert Lee, became a musician and singer, performing in the Hong Kong group The Thunderbirds and later releasing an album dedicated to Bruce titled "The Ballad of Bruce Lee."

While studying at the University of Washington, Bruce met his future wife, Linda Emery, a fellow student aspiring to be a teacher. Despite laws against interracial marriage still existing in many U.S. states at the time, they married in secret on August 17, 1964.

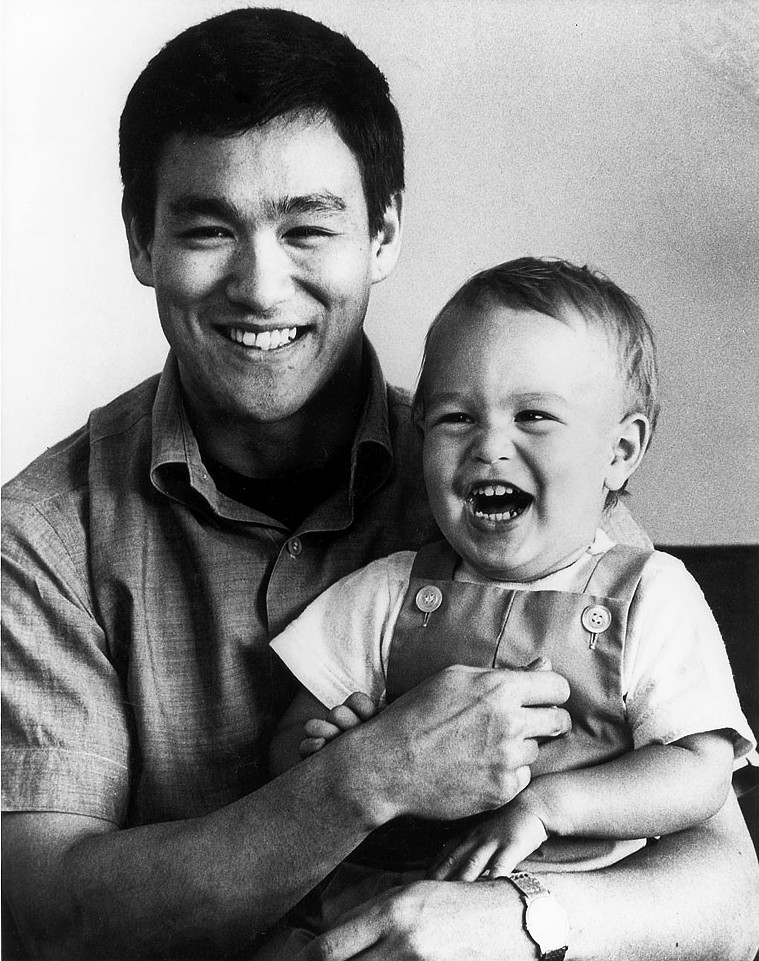

Bruce and Linda had two children: Brandon (born 1965) and Shannon Lee (born 1969). Bruce died when Brandon was eight and Shannon was four. While alive, Lee taught Brandon martial arts and often invited him to film sets, inspiring Brandon's desire to act. Brandon Lee later found success in action films but tragically died at age 28 in 1993 from an accidental prop gun shooting on the set of The Crow. He is buried next to his father in Seattle. Shannon Lee also studied Jeet Kune Do under her father's students, notably Ted Wong, and has been instrumental in preserving and promoting her father's legacy through the Bruce Lee Foundation. Linda Lee Cadwell authored the 1975 book Bruce Lee: The Man Only I Knew, which was adapted into the 1993 feature film Dragon: The Bruce Lee Story. She also wrote The Bruce Lee Story in 1989 and retired from managing the family estate in 2001.

5.2. Friends, Students, and Contemporaries

Bruce Lee cultivated significant relationships with a diverse group of individuals from the martial arts, film, and entertainment industries, many of whom were his students and close confidantes. These connections often led to mutual influence and collaboration.

His pallbearers at his funeral included his brother Robert, and close friends and students such as Taky Kimura, Dan Inosanto, Steve McQueen, James Coburn, and Peter Chin.

- James Coburn: A martial arts student and close friend who collaborated with Lee and Stirling Silliphant on the script for The Silent Flute. Coburn delivered a eulogy at Lee's funeral.

- Steve McQueen: A renowned actor and friend. Lee reportedly admired McQueen's success and aspired to achieve similar stardom.

- Dan Inosanto: A close friend and one of Lee's most prominent disciples. Inosanto continued to teach Lee's art and later trained Bruce's son, Brandon.

- Taky Kimura: Lee's first assistant instructor and a lifelong friend who continued to teach Lee's methods in Seattle.

- Peter Chin: Described by Linda Lee Cadwell as a lifelong family friend and student of Lee.

- James Yimm Lee: Not related by blood, he was one of Lee's three personally certified 3rd rank instructors and co-founded the Jun Fan Gung Fu Institute in Oakland. He was crucial in introducing Lee to Ed Parker, which led to Lee's public demonstrations.

- Roman Polański and Sharon Tate: The Hollywood couple studied martial arts with Lee. Polański flew Lee to Switzerland for training, and Tate trained with him for her role in The Wrecking Crew. After Tate's murder by the Manson Family, Polański initially suspected Lee.

- Stirling Silliphant: A screenwriter, martial arts student, and friend. He collaborated with Lee on The Silent Flute and incorporated Lee's martial arts expertise and philosophy into films like Marlowe and the TV series Longstreet.

- Kareem Abdul-Jabbar: The basketball legend studied martial arts with Lee and developed a close friendship, later appearing in Game of Death.

- Chuck Norris: A karate champion, actor, and friend who was a training partner of Lee's. Their on-screen fight in The Way of the Dragon became iconic. After Lee's death, Norris maintained contact with his family.

- Gene LeBell: A judoka and professional wrestler who became friends with Lee on the set of The Green Hornet. They trained together, exchanging knowledge from their respective martial arts specialties.

5.3. Drug Use

Historical records indicate instances of Bruce Lee's drug use. In July 2021, a private collection of over 40 handwritten letters from Lee to fellow Fist of Fury actor Robert "Bob" Baker was sold at auction for 462.50 K USD. These letters, written between 1967 and 1973, included requests by Lee for Baker to mail him cocaine, pain killers, psilocybin, and other drugs for his personal use.

6. Death

Bruce Lee's untimely death at a young age sparked numerous theories and controversies, further cementing his legendary status.

6.1. Circumstances of Death

On May 10, 1973, Lee experienced a collapse during an automated dialogue replacement (ADR) session for Enter the Dragon at Golden Harvest Film Studio in Hong Kong. He suffered epileptic seizures and headaches and was rushed to Hong Kong Baptist Hospital, where doctors diagnosed cerebral edema (swelling of the brain). The swelling was successfully reduced through the administration of mannitol.

On July 20, 1973, Lee was in Hong Kong planning to have dinner with actor George Lazenby, with whom he intended to make a film. According to his wife, Linda, Lee met producer Raymond Chow at 2 p.m. at his home to discuss the making of Game of Death. They worked until 4 p.m. and then drove to the home of Lee's colleague, Betty Ting Pei, a Taiwanese actress. The three reviewed the script at Ting's home, after which Chow left to attend a dinner meeting.

Lee complained of a headache, and Ting Pei gave him a painkiller, Equagesic, which contained both aspirin and the tranquilizer meprobamate. Around 7:30 p.m., Lee lay down for a nap. When he did not appear for dinner, Chow returned to Ting Pei's apartment but was unable to wake Lee. A doctor was summoned and spent ten minutes attempting to revive Lee before he was transported by ambulance to Queen Elizabeth Hospital. Lee was declared dead on arrival at the age of 32.

6.2. Controversies and Theories on Cause of Death

Lee's iconic status and sudden death led to many rumors and theories, including murder by triads and a supposed curse on him and his family.

Donald Teare, a forensic scientist recommended by Scotland Yard with experience overseeing over 1,000 autopsies, performed an autopsy on Lee. His official conclusion was "death by misadventure" caused by cerebral edema due to a reaction to compounds present in Equagesic. Autopsy reports indicated Lee's brain had swollen from 1,400 to 1,575 grams, a 12.5% increase. While Lee had taken Equagesic many times before, it was determined to be the cause of the fatal allergic reaction.

Initial speculation suggested that cannabis found in Lee's stomach might have contributed to his death. However, Teare stated it would be "irresponsible and irrational" to link cannabis to his collapse or death. Dr. R. R. Lycette, the clinical pathologist at Queen Elizabeth Hospital, also reported at the coroner's hearing that cannabis could not have caused the death.

In a 2018 biography, author Matthew Polly consulted medical experts and theorized that the cerebral edema that killed Lee was caused by over-exertion and heat stroke. Heat stroke was not well understood at the time. Polly further theorized that Lee had his underarm sweat glands removed in late 1972, believing underarm sweat was unphotogenic on film. This procedure, Polly suggested, could have impaired his body's ability to regulate temperature, leading to overheating during practice in hot conditions on May 10 and July 20, 1973, which exacerbated the cerebral edema.

In a December 2022 article in the Clinical Kidney Journal, a team of researchers proposed that Lee's fatal cerebral edema was brought on by hyponatremia, an insufficient concentration of sodium in the blood. They noted several risk factors for hyponatremia in Lee, including excessive water intake, insufficient solute intake, alcohol consumption, and the use or overuse of multiple drugs that impair the kidneys' ability to excrete excess fluids. Lee's symptoms before his death were found to closely match known cases of fatal hyponatremia.

6.3. Funeral and Burial

Lee's funeral was held in Hong Kong and Seattle. In Hong Kong, tens of thousands of fans attended to pay their respects. He was later buried in Lake View Cemetery in Seattle, Washington, next to his son, Brandon Lee.

Pallbearers at Lee's funeral on July 25, 1973, included Taky Kimura, Steve McQueen, James Coburn, Dan Inosanto, Peter Chin, and Lee's brother Robert.

7. Legacy and Cultural Impact

Bruce Lee's influence extends far beyond his lifetime, profoundly shaping martial arts, cinema, and global popular culture, while also breaking significant racial barriers.

7.1. Impact on Martial Arts and Combat Sports

Bruce Lee is widely considered the most influential martial artist of all time. His philosophy and techniques, particularly Jeet Kune Do, are credited with laying the groundwork for modern mixed martial arts (MMA). Lee believed that "the best fighter is not a Boxer, Karate or Judo man. The best fighter is someone who can adapt to any style, to be formless, to adopt an individual's own style and not following the system of styles."

In 2004, Ultimate Fighting Championship (UFC) founder Dana White called Lee the "father of mixed martial arts," stating, "If you look at the way Bruce Lee trained, the way he fought, and many of the things he wrote, he said the perfect style was no style. You take a little something from everything. You take the good things from every different discipline, use what works, and you throw the rest away."

Lee inspired countless individuals to take up martial arts, including numerous fighters in combat sports. Boxing champion Sugar Ray Leonard credited Lee with helping him perfect his jab, while Manny Pacquiao compared his fighting style to Lee's. UFC champion Conor McGregor has also drawn comparisons to Lee, believing Lee would have been a UFC champion in the present day.

Lee's influence led to the foundation of American full-contact kickboxing tournaments by Joe Lewis and Benny Urquidez in the 1970s. American Taekwondo pioneer Jhoon Rhee learned the "accupunch" from Lee, a rapid punch designed to be difficult to block, and incorporated it into American Taekwondo. Rhee later coached heavyweight boxing champion Muhammad Ali, who used the "accupunch" to knock out Richard Dunn in 1975. According to Mike Tyson, "everyone wanted to be Bruce Lee" in the 1970s.

Current UFC Heavyweight Champion Jon Jones cited Lee as inspiration, frequently using the oblique kick to the knee, a technique popularized by Lee. Former UFC Middleweight Champion Anderson Silva has also cited Lee as an inspiration. Numerous other UFC fighters refer to Lee as a "godfather" or "grandfather" of MMA.

7.2. Impact on Film and Popular Culture

Lee was largely responsible for launching the "kung fu craze" of the 1970s. He initially introduced kung fu to the West through American television shows like The Green Hornet and Longstreet, before the craze fully erupted with the dominance of Hong Kong martial arts films in 1973. His success inspired a wave of Western martial arts films and television shows from the 1970s to the 1990s, launching the careers of stars like Jean-Claude Van Damme, Steven Seagal, and Chuck Norris. His influence also led to the broader integration of Asian martial arts into Western action films and television.

Enter the Dragon has been cited as one of the most influential action films of all time. Sascha Matuszak of Vice noted that the film is referenced across various media, with its plot and characters continuing to influence storytellers, and its impact particularly felt in its revolutionary portrayal of African-Americans, Asians, and traditional martial arts. Kuan-Hsing Chen and Beng Huat Chua highlighted the film's influential fight scenes for their spectacle-saturated portrayal of good versus evil.

Many action filmmakers worldwide, including Hong Kong directors like Jackie Chan and John Woo, and Hollywood filmmakers such as Quentin Tarantino and Brett Ratner, have cited Bruce Lee as a formative influence on their careers.

Lee's impact extended to other forms of popular culture:

- Comics**: He influenced several comic book writers, including Marvel Comics founder Stan Lee, who considered Bruce Lee a superhero without a costume. Shortly after his death, Lee inspired Marvel characters like Shang-Chi (debuted 1973) and Iron Fist (debuted 1974), as well as the comic book series The Deadly Hands of Kung Fu (debuted 1974). Stan Lee stated that any martial artist character since then owes their origin to Bruce Lee.

- Breakdancing**: Lee was a formative influence on the development of breakdancing in the 1970s. Early pioneers like the Rock Steady Crew drew inspiration from kung fu moves performed by Lee, inspiring dance moves such as the windmill.

- Indian Cinema**: Lee's films influenced Hindi masala films. After the success of films like Enter the Dragon in India, films like Deewaar (1975) and later Hindi films incorporated fight scenes inspired by 1970s Hong Kong martial arts films. Indian film star Aamir Khan recalled that in the 1970s, "almost every house had a poster of Bruce Lee" in Bombay.

- Japanese Manga and Anime**: The manga and anime franchises Fist of the North Star (1983-1988) and Dragon Ball (1984-1995) were inspired by Lee's films. In turn, these series set trends for popular shōnen manga and anime from the 1980s onwards. Spike Spiegel, the protagonist from the 1998 anime Cowboy Bebop, practices Jeet Kune Do and quotes Lee.

- Video Games**: Bruce Lee films like Game of Death and Enter the Dragon were foundational for video game genres such as beat 'em up action games and fighting games. The first beat 'em up game, Kung-Fu Master (1984), was based on Lee's Game of Death. The Street Fighter video game franchise (debuted 1987), inspired by Enter the Dragon, set the template for all fighting games that followed. Nearly every major fighting game franchise has since included a character based on Bruce Lee. In April 2014, Lee was named a featured character in the combat sports video game EA Sports UFC.

- Parkour**: In France, the Yamakasi cited Bruce Lee's martial arts philosophy as an influence on their development of the parkour discipline in the 1990s, alongside Jackie Chan's acrobatics. The Yamakasi considered Lee their "unofficial president."

7.3. Breaking Racial Barriers and Stereotypes

Lee is widely credited with helping to change the way Asians were presented in American films. He defied prevalent Asian stereotypes, particularly the emasculated Asian male stereotype. His friend Amy Sanbo recalled, "In a time when so many Asians were trying to convince themselves they were white, Bruce was so proud to be Chinese he was busting with it."

In contrast to earlier depictions of Asian men as emasculated, childlike, coolies, or domestic servants, Lee demonstrated that Asian men could be "tough, strong and sexy," according to University of Michigan lecturer Hye Seung Chung. His popularity, in turn, inspired a new Asian stereotype: the martial artist.

In North America, his films initially resonated strongly with black, Asian, and Hispanic audiences. Within black communities, Lee's popularity in the 1970s was second only to heavyweight boxer Muhammad Ali. As he broke through to the mainstream, he became a rare non-white movie star in a Hollywood industry then dominated by white actors. Rapper LL Cool J noted that Lee's films were often the first time many non-white American children had seen a non-white action hero on the big screen in the 1970s.

7.4. Tributes and Honors

Lee has received numerous tributes and honors globally, underscoring his enduring legacy.

- Time named Lee one of the 100 most important people of the 20th century.

- A biography about him had sold over 4 M copies by 1988.

- In 2008, a Chinese television drama series based on his life, The Legend of Bruce Lee, was watched by over 400 M viewers in China, making it the most-watched Chinese television drama series of all time as of 2017.

- In 2024, a proposal was made to erect a statue of Bruce Lee in San Francisco's Chinatown, with his daughter Shannon Lee supporting the initiative, highlighting the Bay Area's significance to his legacy.

His likeness and image have appeared in hundreds of commercials worldwide posthumously. In 2008, Nokia launched an internet campaign with staged "documentary-looking" footage of Bruce Lee playing ping-pong with his nunchaku and igniting matches thrown at him, which went viral and caused confusion about their authenticity.

Notable awards and honors include:

- 1972: Golden Horse Awards Best Mandarin Film for Fist of Fury (Special Jury Award).

- 1994: Hong Kong Film Award for Lifetime Achievement.

- 1999: Named one of the 100 most influential people of the 20th century by Time.

- 2004: Star of the Century Award.

- 2013: The Asian Awards Founders Award.

Statues dedicated to Bruce Lee include:

- A statue unveiled on June 15, 2013, in Chinatown Central Plaza, Los Angeles.

- A 8.2 ft (2.5 m) bronze statue of Lee unveiled on November 27, 2005, on what would have been his 65th birthday, at the Avenue of Stars, Hong Kong.

- A 5.5 ft (1.68 m) bronze statue unveiled in Mostar, Bosnia and Herzegovina, the day before the Hong Kong statue. Supporters cited Lee as a unifying symbol against ethnic divisions in the country.

His former Hong Kong home at 41 Cumberland Road, Kowloon, was planned to be preserved and transformed into a tourist site by Yu Pang-lin in 2009. Although this plan did not materialize after Yu's death in 2015, Yu's grandson, Pang Chi-ping, announced in 2018 that the mansion would be converted into a center for Chinese studies. A theme park dedicated to Lee was also built in Jun'an, Guangdong, China.

8. Filmography

A comprehensive list of his film and television works can be found at Bruce Lee filmography.

9. Books

- Chinese Gung-Fu: The Philosophical Art of Self Defense (1963)

- Tao of Jeet Kune Do (Published posthumously, 1973)

- Bruce Lee's Fighting Method (Published posthumously, 1978)

10. See also

- Bruceploitation

- Jeet Kune Do

- Media about Bruce Lee

- List of stars on the Hollywood Walk of Fame - Bruce Lee at 6933 Hollywood Blvd

- Ip Man

- Linda Lee Cadwell

- Brandon Lee

- Shannon Lee

- Chuck Norris

- Dan Inosanto

- James Coburn

- Steve McQueen

- Kareem Abdul-Jabbar

- Raymond Chow

11. Further Reading

- Clouse, Robert. Bruce Lee: The Biography. Unique Publications, 1988.

- Glover, Jesse R. Bruce Lee's Non-Classical Gung Fu. Glover Publications, 1978.

- Lee, Bruce. Jeet Kune Do: Bruce Lee's Commentaries on the Martial Way. C.E. Tuttle Co., 1997.

- Lee, Bruce. The Tao of Gung Fu: A Study in the Way of Chinese Martial Art. C.E. Tuttle, 1997.

- Lee, Bruce. Words of the Dragon: Interviews 1958-1973. C.E. Tuttle, 1997.

- Lee, Bruce. Striking Thoughts: Bruce Lee's Wisdom for Daily Living. Tuttle Pub., 2000.

- Polly, Matthew. Bruce Lee: A Life. Simon & Schuster, 2018.

- Thomas, Bruce. Bruce Lee: Fighting Spirit: a Biography. Frog Books, 1994.

- Uyehara, Mitoshi. Bruce Lee: The Incomparable Fighter. Ohara Publications, 1988.