1. Overview

Alberto Ascari was a highly accomplished Italian racing driver who dominated the early years of the Formula One World Championship. Born on July 13, 1918, in Milan, he became the first driver to secure two consecutive Formula One World Drivers' Championship titles, achieving this feat with Scuderia Ferrari in the 1952 and 1953 seasons. Known for his meticulous precision and calm analytical approach to racing, Ascari was affectionately nicknamed "Ciccio" (meaning "Tubby") or "The Flying Milanese" (フライング・ミランFuraingu MiranJapanese) due to his origin. His career, though tragically cut short at the age of 36, mirrored that of his father, Antonio Ascari, also a renowned racing driver, who died at the same age and on the same day of the month. Alberto Ascari remains the last Italian to win the Formula One World Drivers' Championship and holds several significant records in the sport, cementing his place as one of its greatest figures. Beyond Formula One, he was also a successful endurance racer, notably winning the Mille Miglia in 1954 with Lancia.

2. Early life and background

Alberto Ascari's life was profoundly shaped by his family's deep connection to motorsport, particularly the influential and tragic career of his father.

2.1. Childhood and family

Alberto Ascari was born in Milan, Kingdom of Italy, on July 13, 1918. His father, Antonio Ascari, was a highly talented Grand Prix motor racing star during the 1920s, competing for Alfa Romeo. A profound and defining event in Alberto's childhood occurred just two weeks before his seventh birthday: his father was killed in an accident while leading the 1925 French Grand Prix at the Autodrome de Linas-Montlhéry. Despite this tragedy, Alberto developed an intense interest in racing, which he once famously described by saying, "I only obey one passion, racing. I wouldn't know how to live without it." His dedication was so strong that he reportedly ran away from school twice and sold his textbooks to fund his early racing endeavors.

In 1940, Ascari married Mietta Tavola, with whom he had two children.

2.2. Early career and World War II

Before transitioning to car racing, Alberto Ascari began his career on motorcycles. At the age of 19, he was signed to ride for the Bianchi team. His move to four-wheel racing became more consistent after he entered the prestigious Mille Miglia in 1940. For this event, he drove an Auto Avio Costruzioni 815, a car supplied by his father's close friend, Enzo Ferrari, whose company was a precursor to Ferrari.

With the onset of World War II, Ascari's racing activities were temporarily halted. During this period, the family garage, which Ascari was now running, was conscripted to service and maintain vehicles for the Italian military. He and his close friend and fellow racing driver, Luigi Villoresi, formed a lucrative transport business, supplying fuel to army depots in North Africa. This partnership notophytes not only established a lasting friendship and mentorship between them but also provided them with an exemption from military service. The two narrowly survived an incident when a ship they were on, carrying lorries, capsized in Tripoli harbor.

3. Motor racing career

Following World War II, Alberto Ascari embarked on a distinguished motor racing career, marked by early successes before the formal establishment of the Formula One World Championship, followed by a period of unprecedented dominance.

3.1. Post-World War II successes

After the end of World War II, Ascari returned to racing, initially competing in Grands Prix with the Maserati 4CLT. His teammate was Luigi Villoresi, who became a crucial mentor and friend to Ascari. The pair quickly found success on the circuits of Northern Italy. Ascari earned the nickname Ciccio, meaning "Tubby", due to his slightly chubby build.

The FIA introduced Formula One regulations in 1946, laying the groundwork for a new championship structure. Over the next four transitional years before the official World Championship began, Ascari was at the peak of his performance, securing numerous victories across Europe. His first significant win came at the 1948 San Remo Grand Prix. He also achieved a second-place finish at the 1948 British Grand Prix, organized by the Royal Automobile Club at the Silverstone Circuit, an event often considered the first British Grand Prix. Driving for Maserati, he also won the first 1949 Buenos Aires Grand Prix.

Ascari's career took a significant turn when he and Villoresi signed with Scuderia Ferrari. Enzo Ferrari, having been a close friend and teammate to Ascari's late father, had a keen interest in Alberto's racing progress. In 1949, driving for Ferrari, Ascari won three more races, including the 1949 Swiss Grand Prix, which marked Ferrari's first international Grand Prix victory. He also triumphed at the European Grand Prix held at the Monza Circuit, solidifying his status as a leading Italian driver.

3.2. Formula One World Championship debut (1950-1951)

The inaugural Formula One World Championship season commenced in 1950. The Ferrari team made its World Championship debut at the 1950 Monaco Grand Prix, the second race of the season. Ascari, along with Villoresi and French driver Raymond Sommer, comprised the team. At Monaco, Ascari made an immediate impact, finishing second, just one lap behind Juan Manuel Fangio, and becoming the youngest driver at 31 years and 312 days to score points and a podium position in Formula One.

Ferrari faced challenges that year, as their supercharged Ferrari 125 F1 proved too slow to effectively challenge the dominant Alfa Romeo team. Consequently, Ferrari began developing an unblown 4.5-litre car. Much of the 1950 season was spent enlarging the team's 2-litre Formula Two engine. When the full 4.5-litre Ferrari 375 F1 finally arrived for the 1950 Italian Grand Prix, the championship's final round, Ascari provided Alfa Romeo with their strongest challenge of the year before retiring. He then took over his teammate Dorino Serafini's car to finish second. The new Ferrari 375 F1 then went on to win the non-championship 1950 Penya Rhin Grand Prix.

Throughout the 1951 season, Ascari emerged as a significant threat to the Alfa Romeo team, although initial unreliability hampered his progress. After securing victories at the 1951 German Grand Prix at Nürburgring and the 1951 Italian Grand Prix, he was only two points behind Fangio in the championship standings leading into the decisive 1951 Spanish Grand Prix. Despite securing pole position, a critical and ultimately disastrous tire choice for the Ferraris meant they were unable to challenge Fangio. Ascari finished fourth, and Fangio won the race and his first title, with the 33-year-old Ascari becoming the youngest runner-up.

3.3. Dominance and consecutive World Championships (1952-1953)

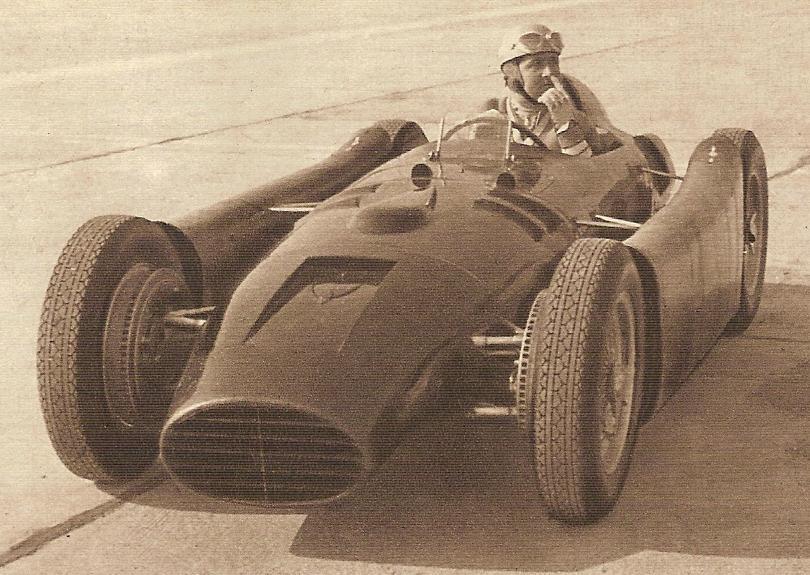

The 1952 and 1953 Formula One seasons marked the pinnacle of Alberto Ascari's career, as he achieved back-to-back World Championships with Scuderia Ferrari. For the 1952 season, the World Championship utilized the 2-litre Formula Two regulations, and Ascari drove the formidable Ferrari 500. He missed the 1952 Swiss Grand Prix to compete in the 1952 Indianapolis 500, which was then a World Championship event. Ascari was the sole European driver to race at Indy during its eleven years on the World Championship schedule. His race, however, ended after 40 laps due to a wheel collapse, preventing him from making a significant impression.

Upon returning to Europe, Ascari embarked on an unparalleled winning streak, securing victory in all six remaining rounds of the series to decisively clinch his first world title. He also claimed five non-championship wins during this period. In each of his championship race victories, he recorded the fastest lap. His dominant performance allowed him to score the maximum possible number of points a driver could earn that year, as only the best four of eight scores counted towards the World Championship. At 34 years old, Ascari became Formula One's youngest champion at the time, a record that stood until Mike Hawthorn, who was his teammate in 1951, won the championship in 1958 at the age of 29. Notably, Juan Manuel Fangio missed most of the 1952 season following a crash in June.

Ascari's dominance continued into the 1953 season, which he began with three more consecutive race victories. This extended his winning streak in championship races (excluding Indy) to an unprecedented nine straight wins. This remarkable run finally ended when he finished fourth at the highly competitive 1953 French Grand Prix. He secured two more wins later in the year, clinching his second consecutive World Championship and becoming Formula One's first two-time champion. At 35, he was also the youngest two-time champion and the youngest back-to-back champion, records later surpassed by Jack Brabham in 1960. The 1953 season is often regarded as the high point of Ascari's career. He faced the returning Fangio in the opening race, the 1953 Argentine Grand Prix in Buenos Aires, in front of Fangio's home crowd. Despite expectations of a strong challenge from a resurgent Maserati with Fangio at the helm, Ascari took pole position and secured a decisive victory, setting the stage for his second and final World Championship.

3.4. Transition to Lancia and final season (1954-1955)

At the end of the 1953 season, following a dispute over his salary, Alberto Ascari departed Ferrari and signed with Lancia for the 1954 campaign. However, the development of Lancia's new car experienced significant delays. The Lancia D50 was not ready until the final race of the season. During this waiting period, Gianni Lancia allowed Ascari to guest drive for other teams: he competed twice for Maserati, even sharing the fastest lap at the 1954 British Grand Prix, and once for Ferrari.

Despite the Formula One setbacks, Ascari achieved a significant victory in 1954 by winning the prestigious Mille Miglia endurance race, driving a Lancia sports car. He navigated through dreadful weather and overcame a mechanical issue when a throttle spring failed, which he temporarily replaced with a rubber band. When the Lancia D50 finally debuted at the 1954 Spanish Grand Prix, Ascari immediately demonstrated its potential by securing pole position and leading impressively early in the race, also setting the fastest lap, before being forced to retire due to a clutch problem. His decision to move to Lancia is often considered a low point in his career, as the promised new car and increased salary materialized only near the season's end, by which time Fangio had built an insurmountable lead. Ascari finished the 1954 season without completing any of the four Grands Prix he entered.

Ascari's 1955 season began with promising results, as the Lancia D50 secured victories in non-championship races at Turin (Parco del Valentino) and the Naples Grand Prix, where the Lancias notably outperformed the previously dominant Mercedes. In a World Championship event, the 1955 Argentine Grand Prix, he retired from the race.

Tragedy nearly struck during the 1955 Monaco Grand Prix on May 22. While leading the race, Ascari crashed into the harbor after missing a chicane, reportedly distracted either by the crowd's reaction to Stirling Moss's retirement or the close proximity of the lapped Cesare Perdisa. Approaching the chicane too quickly, he steered his D50 through the hay bales and sandbags, plunging into the sea but narrowly missing a substantial iron bollard by about 12 in (30 cm). Although his car sank, Ascari was quickly pulled into a boat and miraculously escaped with only a broken nose, appearing relatively unharmed.

4. Death

Alberto Ascari's life ended tragically just four days after his lucky escape at Monaco, under mysterious circumstances that deepened the sense of fate surrounding his family.

4.1. Circumstances of the fatal accident

On May 26, 1955, Alberto Ascari visited the Autodromo Nazionale Monza to watch his friend, Eugenio Castellotti, test a Ferrari 750 Monza sports car. Ascari and Castellotti were scheduled to co-drive the car in the upcoming 1000 km Monza race, having received special permission from Lancia to do so. Although Ascari was not scheduled to drive that day, he decided to take a few laps. In an unusual departure from his superstitious routine, he set off in street clothes and, notably, wearing Castellotti's white helmet instead of his own lucky blue helmet, which he had left at home. He reportedly reasoned that getting back to racing as soon as possible after his Monaco crash was the best way to recover.

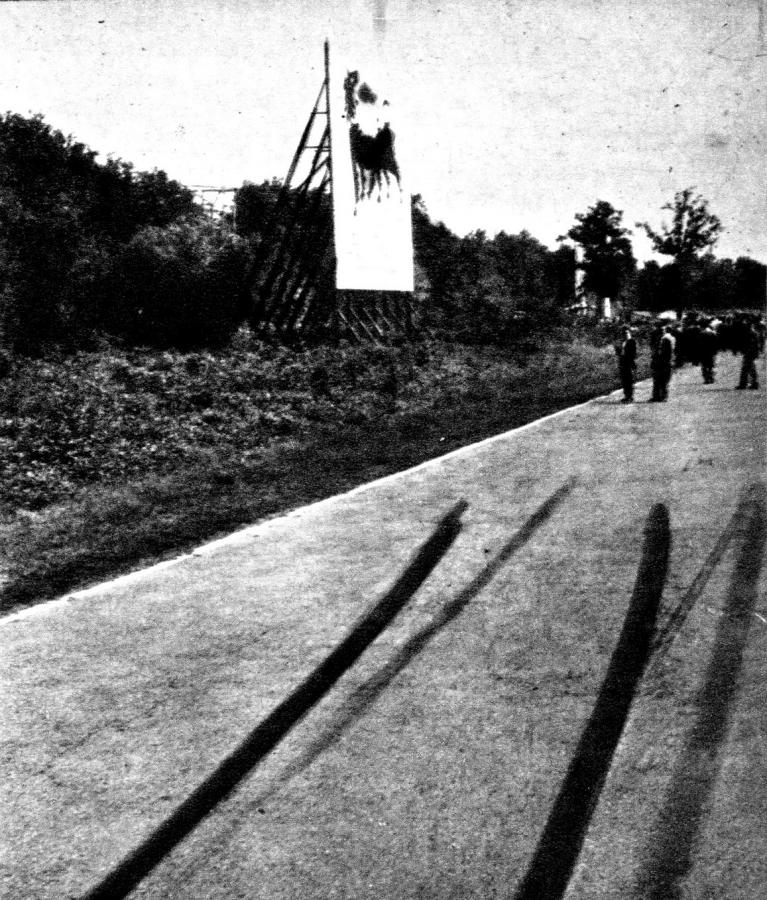

On his third lap, as he emerged from a fast curve known as the Curva del Vialone, the car inexplicably skidded, flipped onto its nose, and somersaulted twice. Ascari was thrown from the vehicle onto the track, suffering multiple injuries, and died within minutes. The corner where the accident occurred was subsequently renamed in his honor, and later replaced with a chicane called Variante Ascari.

The precise reasons and circumstances of the accident have never been fully explained. Ascari was renowned for his meticulous attention to safety, making his decision to drive another's car without his usual lucky helmet a point of enduring mystery. While some have speculated about a spectator crossing the track, this hypothesis has been largely excluded by witnesses. In 2001, the Swiss newspaper Rinascita published an account from Angelo Consonni, who, as a seven-year-old at the time, was near the Curva del Vialone and observed two workers attempting to cross the track just before the crash. He recalled a sudden silence before seeing the Ferrari spin and overturn. Fellow driver Ernesto Brambilla confirmed in 2014 that he witnessed the car spin and overturn, dismissing the spectator theory. Luigi Villoresi, Ascari's close friend, suggested that Ascari might have been afraid of being afraid, implying a psychological component following his Monaco incident.

4.2. Aftermath and reactions

News of Alberto Ascari's death sent shockwaves through the motor racing world, and fans from all corners mourned his loss. He was laid to rest next to his father's grave in the Cimitero Monumentale in Milan, a fitting final resting place for a legendary racer. More than a million people lined the streets of Milan for his funeral, a testament to his immense popularity and the grief felt by the public.

His distraught wife, Mietta Ascari, confided in Enzo Ferrari that she would have taken her own life were it not for their children. Poignantly, just three days before his death, Ascari had told a friend: "I never want my children to become too fond of me because one day I might not come back and they will suffer less if I don't come back."

Fellow drivers and competitors expressed their profound sorrow. His friend and rival, Juan Manuel Fangio, lamented: "I have lost my greatest opponent. Ascari was a driver of supreme skill and I felt my title last year lost some of its value because he was not there to fight me for it. A great man." Stirling Moss remembered Ascari as "wonderfully good... he was rather better than good, he was very good indeed. He may have been as fast as Fangio... but he had not got the polish that so distinguished Fangio." Mike Hawthorn, another peer, stated that "Ascari was the fastest driver I ever saw. And when I say that, I include Fangio."

Ascari's death is widely considered a contributing factor to Lancia's withdrawal from motor racing in 1955, occurring just three days after his funeral. While the company was also in significant financial trouble, requiring a government subsidy to survive, the loss of their star driver was a devastating blow. Lancia subsequently handed its team, drivers, cars, and spare parts over to Enzo Ferrari.

The circumstances of Alberto's death bore an eerie resemblance to his father Antonio's, leading to the widely discussed "Ascari family tragedy." Both men died at the exact same age, 36 years and 10 months, and both were killed in accidents on the 26th day of the month - Antonio at Montlhéry 30 years prior. Furthermore, both Ascaris won 13 Grands Prix and often drove car number 26. This tragic pattern fueled Alberto's already deeply superstitious nature; he avoided black cats, was concerned about unlucky numbers, and meticulously guarded his racing briefcase, which contained his "lucky" blue helmet and T-shirt, along with goggles and gloves. He had also made a promise to himself after his father's death that he would never race on the 26th of any month and that he would become the number one racing driver.

5. Legacy and evaluation

Alberto Ascari's enduring legacy in motorsport is characterized by his unique driving style, a personality admired by many, and a historical standing that places him among the sport's all-time greats, despite his relatively short career.

5.1. Driving style and personality

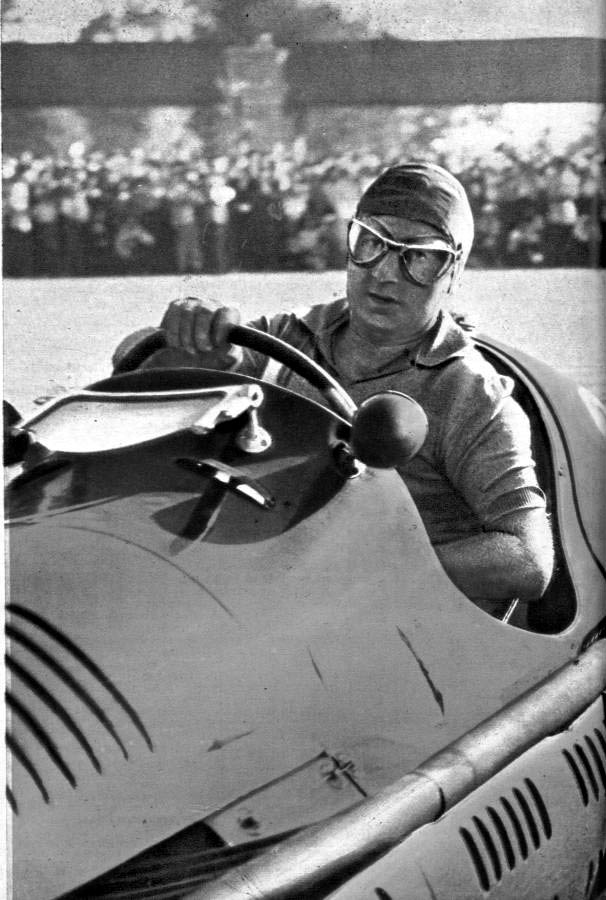

Ascari was highly regarded by both his fellow drivers and the public for his modesty and his willingness to praise the abilities of his rivals. He was considered one of the most challenging drivers to overtake on the track. Enzo Ferrari, reflecting on Ascari's style, noted, "When he had to follow and pass an opponent, he evidently suffered, not from an inferiority complex, but from a nervousness that did not let him express his true class." Ferrari also described Ascari's precise and distinctive driving style, emphasizing that "Ascari had to lead from the start. In that position he was hard to overtake, almost impossible to beat, in my estimation. Alberto was secure when he was playing the hare. That was when his style was at its most superb. In second place, or further back, he was less sure."

BBC Sport's chief Formula One writer, Andrew Benson, offered a vivid description of Ascari, noting that he "did not look much like the modern idea of a Formula 1 driver. His double chin and slightly chubby frame brought to mind a Milanese baker more than the lean, pinched athletes of the modern age. Yet this was a man who, for a period, dominated grand prix racing like no other has before or since." Benson further characterized Ascari as "a ruthless winning machine" with a "phlegmatic character who approached his racing with an analytical style." His distinctive appearance on track, with his pale blue shirt and matching helmet, contrasted with the scarlet Ferraris of the early 1950s. He typically sat upright, hunched slightly forward, closer to the large steering wheel than many of his contemporaries, with his elbows forming sharper angles.

5.2. Historical standing and Formula One records

Despite a career that saw him start fewer Grands Prix than any other Formula One World Champion, Alberto Ascari is widely considered among the greatest drivers in the sport's history. He and Michael Schumacher are Ferrari's only drivers to have won consecutive World Championships, and Ascari remains Ferrari's sole Italian champion. As the first driver to secure multiple World Championship titles, he held the record for most titles from 1952 to 1954.

His rivalry with Juan Manuel Fangio was one of the most compelling in Formula One. From 31 starts each, they collectively achieved 27 wins, 30 pole positions, and 27 fastest laps. In all but two of the 37 Grands Prix from the 1950 British Grand Prix to the 1955 Monaco Grand Prix, either Ascari or Fangio (or both) held the lead for at least one lap, leading a combined 66.6% of 2,508 laps. While Stirling Moss believed Fangio was superior, he conceded that Ascari was "very close," and Denis Jenkinson of Motor Sport magazine considered Ascari the better driver. Ascari has been called the prototype Jim Clark and the last Italian Grand Prix star. Some rivals even considered him faster than Fangio. With a win ratio exceeding 40%, Ascari was second only to Fangio at the time. With Ferrari, where he drove from 1949 to 1953, he achieved 13 wins in 27 races, a remarkable 48% win ratio, which remains the highest for a Ferrari driver.

Ascari's performance during the 1952 season is frequently cited as one of the best single-year performances in Formula One history. He overwhelmingly outperformed several strong Ferrari teammates, including Giuseppe Farina, whom he outscored by a significant margin. According to a 2019 adjusted scoring-rate calculation, the 1952 season featured the largest margin between first and second place in the championship standings of all time, with Ascari averaging 8.90 points per race compared to 4.36 points for Mike Hawthorn.

Into the 21st century, Ascari continues to hold several Formula One records, some of which have since been equaled by other World Champions like Clark, Nigel Mansell, Sebastian Vettel, and Lewis Hamilton. Throughout his career, Ascari achieved seven hat-tricks (pole position, fastest lap, and race win) and five Grand Chelems (in the 1952 French Grand Prix, 1952 German Grand Prix, 1952 Dutch Grand Prix, 1953 Argentine Grand Prix, and 1953 British Grand Prix). As of July 2023, only 26 drivers had secured a Grand Chelem, with a total of 66 occurring. Ascari is one of only three drivers (along with Jim Clark and Sebastian Vettel) to achieve the feat of taking pole, fastest lap, race win, and leading every lap in consecutive races.

Ascari holds the records for most consecutive hat-tricks (4), most consecutive Grand Chelems (2, shared with Clark and Vettel), highest number of Grand Chelems in a season (3, shared with Clark, Mansell, and Hamilton), most consecutive fastest laps (7), most consecutive laps in the lead (304), and most consecutive distance led (1.3 K mile (2.08 K km)). He also holds the highest percentage of fastest laps in a season (75%) and the highest percentage of possible championship points in a season (100%, shared with Clark). His 51-year record for most consecutive wins (7), which some sources extend to nine by excluding the intervening 1953 Indianapolis 500 (as few European drivers competed in it when it was part of the Drivers' Championship), was first equaled by Michael Schumacher in 2004, then surpassed by Sebastian Vettel (9) in 2013, and again by Max Verstappen (10) in 2023. Additionally, Ascari held the record for the highest percentage of wins in a season (75%) until 2023, when Max Verstappen broke his 71-year-old record.

Various quantitative analyses consistently rank Ascari among the top Formula One drivers of all time. In a 2009 Autosport survey of 217 Formula One drivers, he was voted the 16th-greatest. The BBC listed him as the 9th-greatest in 2012. Carteret Analytics, using quantitative analysis, ranked him as the fourth-best driver of all time in 2020. Other objective mathematical models, such as Eichenberger and Stadelmann (2009, 12th), original F1metrics (2014, 9th), FiveThirtyEight (2018, 19th), and updated F1metrics (2019, 5th), consistently place Ascari within the top 20.

5.3. Tributes and memorials

Alberto Ascari's contributions and tragic story have been commemorated in various ways, reflecting his enduring impact on motorsport. A street in Rome, in the Esposizione Universale Roma area, is named in his honor. Both the Autodromo Nazionale Monza and the Autodromo Oscar Alfredo Gálvez feature chicanes named after him; in 1972, one of the chicanes at Monza was specifically named Variante Ascari.

In 1992, he was inducted into the International Motorsports Hall of Fame. The British supercar manufacturer Ascari Cars, founded in 1994, bears his name as a tribute. Italian-born American racing legend Mario Andretti counts Ascari among his racing heroes, having watched him compete at the Monza circuit in his youth. Ascari was also inducted into the FIA Hall of Fame in December 2017. His story is also featured in Mark Sullivan's novel Beneath a Scarlet Sky. In 2015, Ascari was included in the Walk of Fame of Italian sport. Sadly, in 2016, unknown thieves stole the bronze busts of Ascari and his father, which were located on the sides of their shrine. Alberto's bust was sculpted by Michele Vedani, while his father's was by Orazio Grossoni.

6. Racing record

Alberto Ascari's racing career spanned various categories, showcasing his versatile talent and remarkable achievements in both Grand Prix racing and endurance events.

6.1. Career highlights

| Season | Series | Position | Team | Car |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1947 | Sehab Almaz Bey Trophy | 2nd | Cisitalia-Fiat D46 | |

| 1948 | Gran Premio di San Remo | 1st | Maserati 4CLT/48 | |

| Circuito di Pescara | 1st | Maserati A6GCS | ||

| RAC International Grand Prix | 2nd | Maserati 4CLT/48 | ||

| Grand Prix de l'ACF | 3rd | Alfa Romeo 158 | ||

| 1949 | Gran Premio del General Juan Perón y de la Ciudad Buenos Aires | 1st | Scuderia Ambrosiana | Maserati 4CLT |

| Gran Premio di Bari | 1st | Scuderia Ferrari | Ferrari 166C | |

| Grand Prix de Suisse | 1st | Ferrari 125 | ||

| Coupe des Petites Cylindrées | 1st | Scuderia Ferrari | Ferrari 166C | |

| Daily Express BRDC International Trophy | 1st | Ferrari 125 | ||

| Lausanne Grand Prix | 1st | |||

| Gran Premio d'Italia | 1st | |||

| Gran Premio del General Juan Perón y de la Ciudad Buenos Aires | 1st | Scuderia Ferrari | Ferrari 166 FL | |

| Copa Acción de San Lorenzo | 3rd | Maserati Ambrosiana | Maserati 4CLT | |

| Grand Prix de Belgique | 3rd | Scuderia Ferrari | Ferrari 125 | |

| Gran Premio dell'Autodromo di Monza | 3rd | Ferrari 166C | ||

| 1950 | Gran Premio Internacional del General San Martín | 1st | Scuderia Ferrari | Ferrari 166 FL |

| Gran Premio di Modena | 1st | Ferrari 166 F2/50 | ||

| Grand Prix de Mons | 1st | |||

| Grand Prix de Luxembourg | 1st | Ferrari 166 MM | ||

| Gran Premio di Roma | 1st | Ferrari 166 F2/50 | ||

| Coupe ds Petites Cylindrées | 1st | |||

| Großer Preis von Deutschland | 1st | |||

| Circuito del Garda | 1st | |||

| Grand Premio do Penya Rhin | 1st | Ferrari 375 | ||

| Grand Prix de Marseilles | 2nd | Ferrari 166 F2/50 | ||

| Grand Prix Automobile de Monaco | 2nd | Ferrari 125 | ||

| Gran Premio dell'Autodromo di Monza | 2nd | Ferrari 166 F2/50 | ||

| Gran Premio d'Italia | 2nd | Ferrari 125 | ||

| Grote Prijs van Nederland | 3rd | Ferrari 166 | ||

| 1950 Formula One season FIA Formula One World Championship | 5th | Ferrari 125 | ||

| 1951 | Rallye del Sestriere | 1st | Lancia Aurelia | |

| Gran Premio di San Remo | 1st | Ferrari 375 | ||

| Gran Premio dell'Autodromo di Monza | 1st | Scuderia Ferrari | Ferrari 166 F2/50 | |

| Gran Premio di Napoli | 1st | |||

| Großer Preis von Deutschland | 1st | Ferrari 375 | ||

| Gran Premio d'Italia | 1st | |||

| Gran Premio di Modena | 1st | Ferrari 500 | ||

| 1951 Formula One season FIA Formula One World Championship | 2nd | Ferrari 375 | ||

| Grote Prijs van Belgie | 2nd | |||

| Grand Prix de l'A.C.F. | 2nd | |||

| Carrera Panamericana | 2nd | Centro Deportivo Italiano | Ferrari 212 Inter Vignale | |

| 1952 | 1952 Formula One season FIA Formula One World Championship | 1st | Scuderia Ferrari | Ferrari 500 |

| Grand Prix de France | 1st | |||

| Gran Premio di Siracusa | 1st | |||

| Grand Prix Automobile de Pau | 1st | |||

| Grand Prix de Marseille | 1st | |||

| Grote Prijs van Belgie | 1st | |||

| Grand Prix de l'ACF | 1st | |||

| RAC British Grand Prix | 1st | |||

| Großer Preis von Deutschland | 1st | |||

| Grand Prix du Comminges | 1st | |||

| Grote Prijs van Nederland | 1st | |||

| Grand Prix de La Baule | 1st | |||

| Gran Premio d'Italia | 1st | |||

| Grand Prix de la Marne | 3rd | |||

| Gran Premio di Modena | 3rd | |||

| 1953 | 1953 Formula One season FIA Formula One World Championship | 1st | Scuderia Ferrari | Ferrari 500 |

| Gran Premio de la Republica Argentina | 1st | |||

| Grand Prix Automobile de Pau | 1st | |||

| Grand Prix de Bordeaux | 1st | |||

| Grote Prijs van Nederland | 1st | |||

| Grote Prijs van Belgie | 1st | |||

| RAC British Grand Prix | 1st | |||

| Großer Preis der Schweiz | 1st | |||

| Internationales ADAC-1000 km Rennen Weltmeisterschaftslauf Nürburgring | 1st | Automobili Ferrari | Ferrari 375 MM Vignale Spyder | |

| 12 Hours of Casablanca | 2nd | Scuderia Ferrari | Ferrari 500 Mondial | |

| 1954 | Mille Miglia | 1st | Scuderia Lancia | Lancia D24 |

| 1954 Formula One season FIA Formula One World Championship | 25th | Officine Alfieri Maserati | Maserati 250F | |

| 1955 | Gran Premio del Valentino | 1st | Scuderia Lancia | Lancia D50 |

| Gran Premio di Napoli | 1st | Scuderia Lancia | Lancia D50 |

6.2. Complete Formula One World Championship results

(Races in bold indicate pole position; Races in italics indicate fastest lap)

| Year | Entrant | Chassis | Engine | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | World Drivers' Championship | Points |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1950 | Scuderia Ferrari | Ferrari 125 | Ferrari 125 1.5 V12s | GBR | 2 | 500 | Ret | 5th | 11 | |||||

| Ferrari 275 | Ferrari 275 3.3 V12 | 5 | DNS | |||||||||||

| Ferrari 375 | Ferrari 375 4.5 V12 | 2* | ||||||||||||

| 1951 | Scuderia Ferrari | Ferrari 375 | Ferrari 375 4.5 V12 | 6 | 500 | 2 | 2† | Ret | GER | ITA | ESP | 2nd | 25 (28) | |

| 1952 | Scuderia Ferrari | Ferrari 375S | Ferrari 375 4.5 V12 | Ret | 1st | 36 (53 1/2) | ||||||||

| Ferrari 500 | Ferrari 500 2.0 L4 | SUI | BEL | FRA | GBR | GER | NED | ITA | ||||||

| 1953 | Scuderia Ferrari | Ferrari 500 | Ferrari 500 2.0 L4 | ARG | 500 DNA | NED | BEL | FRA | GBR | GER | SUI | ITA Ret | 1st | 34 1/2 (46 1/2) |

| 1954 | Officine Alfieri Maserati | Maserati 250F | Maserati 250F1 2.5 L6 | ARG | 500 | BEL | Ret | Ret | GER | SUI | 25th | 1 1/7 | ||

| Scuderia Ferrari | Ferrari 625 | Ferrari 625 2.5 L4 | Ret | |||||||||||

| Scuderia Lancia | Lancia D50 | Lancia DS50 2.5 V8 | Ret | |||||||||||

| 1955 | Scuderia Lancia | Lancia D50 | Lancia DS50 2.5 V8 | Ret | Ret | 500 | BEL | NED | GBR | ITA | NC | 0 |

- Indicates shared drive with Dorino Serafini

† Indicates shared drive with José Froilán González

‡ Indicates shared drive with Luigi Villoresi

6.3. Complete Non-Championship Formula One results

(Races in bold indicate pole position; Races in italics indicate fastest lap)

| Year | Entrant | Chassis | Engine | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | 13 | 14 | 15 | 16 | 17 | 18 | 19 | 20 | 21 | 22 | 23 | 24 | 25 | 26 | 27 | 28 | 29 | 30 | 31 | 32 | 33 | 34 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1950 | Scuderia Ferrari | Ferrari 166 F2-50 | Ferrari 166 F2 2.0 V12 | Ret | RIC | Ret | JER | 3 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Ferrari 125 | Ferrari 125 1.5 V12s | Ret | PAR | EMP | Ret | 4 | NOT | ULS | PES | STT | DNQ | GOO | |||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Ferrari 375 | Ferrari 375 4.5 V12 | 1 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 1951 | Scuderia Ferrari | Ferrari 375 | Ferrari 375 4.5 V12 | Ret | Ret | RIC | 1 | BOR | INT | PAR | ULS | SCO | NED | ALB | Ret | Ret | GOO | ||||||||||||||||||||

| 1952 | Scuderia Ferrari | Ferrari 500 | Ferrari 500 2.0 L4 | 1 | 1 | IBS | 1 | AST | INT | ELÄ | NAP | EIF | PAR | ALB | FRO | ULS | Ret | LAC | ESS | 3* | Ret | CAE | DMT | 1† | NAT | 1 | 3‡ | CAD | SKA | MAD | AVU | JOE | NEW | ||||

| Ferrari 375 | Ferrari 375 4.5 V12 | 5 | RIC | LAV | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 1953 | Scuderia Ferrari | Ferrari 500 | Ferrari 500 2.0 L4 | Ret | 1 | LAV | AST | 1 | INT | ELÄ | 5 | ULS | WIN | FRO | COR | EIF | |||||||||||||||||||||

| Ferrari 375 | Ferrari 375 4.5 V12 | DNQ | PRI | ESS | MID | ROU | CRY | AVU | USF | LAC | BRI | CHE | SAB | NEW | CAD | RED | SKA | LON | MOD | MAD | JOE | CUR | |||||||||||||||

| 1955 | Scuderia Lancia | Lancia D50 | Lancia DS50 2.5 V8 | 1 | 5 | GLO | BOR | INT | 1 | ALB | CUR | COR | LON | DRT | RED | DTT | OUL | AVO | SYR |

- Indicates shared drive with Luigi Villoresi

† Indicates shared drive with André Simon

‡ Indicates shared drive with Sergio Sighinolfi

6.4. Complete endurance racing results

Alberto Ascari competed in various endurance races, demonstrating his versatility beyond single-seater championships.

6.4.1. Complete 24 Hours of Le Mans results

| Year | Team | Co-Drivers | Car | Class | Laps | Overall Position | Class Position |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1952 | Scuderia Ferrari | Luigi Villoresi | Ferrari 250 S Berlinetta Vignale | S3.0 | DNF | DNF | |

| 1953 | Scuderia Ferrari | Luigi Villoresi | Ferrari 340 MM Pininfarina Berlinetta | S5.0 | 229 | DNF | DNF |

6.4.2. Complete 12 Hours of Sebring results

| Year | Team | Co-Drivers | Car | Class | Laps | Overall Position | Class Position |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1954 | Scuderia Lancia Co. | Luigi Villoresi | Lancia D24 | S5.0 | 87 | DNF | DNF |

6.4.3. Complete 24 Hours of Spa results

| Year | Team | Co-Drivers | Car | Class | Laps | Overall Position | Class Position |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1953 | Scuderia Ferrari | Luigi Villoresi | Ferrari 375 MM Pininfarina Berlinetta | S | 216 | DNF | DNF |

6.4.4. Complete Mille Miglia results

| Year | Team | Co-Drivers | Car | Class | Overall Position | Class Position |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1940 | Alberto Ascari | Giovanni Minozzi | Auto Avio Costruzioni 815 | 1.5 | DNF | DNF |

| 1948 | Scuderia Ambrosiana | Guerino Bertocchi | Maserati A6GCS | S2./+2.0 | DNF | DNF |

| 1950 | Scuderia Ferrari | Senesio Nicolini | Ferrari 275 S Barchetta Touring | S+2.0 | DNF | DNF |

| 1951 | Scuderia Ferrari | Senesio Nicolini | Ferrari 340 America Barchetta Touring | S/GT+2.0 | DNF | DNF |

| 1954 | Scuderia Lancia | Lancia D24 | S+2.0 | 1st | 1st |

6.4.5. Complete Carrera Panamericana results

| Year | Team | Co-Drivers | Car | Class | Overall Position | Class Position |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1951 | Centro Deportivo Italian | Luigi Villoresi | Ferrari 212 Inter Vignale | IC | 2nd | 2nd |

| 1952 | Industrias 1-2-3 | Giuseppe Scotuzzi | Ferrari 340 Mexico Vignale Spyder | S | DNF | DNF |

6.4.6. Complete 12 Hours of Casablanca results

| Year | Team | Co-Drivers | Car | Class | Overall Position | Class Position |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1953 | Scuderia Ferrari | Casimiro de Oliveira | Ferrari 375 MM | S+2.0 | DNS | DNS |

| Scuderia Ferrari | Luigi Villoresi | Ferrari 500 Mondial | S2.0 | 2nd | 1st |

6.5. Indianapolis 500 results

| Year | Chassis | Engine | Start | Finish | Team |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1952 | Ferrari 375 Special | Ferrari | 19 | 31 | Scuderia Ferrari |

6.6. Formula One records

Alberto Ascari holds several notable Formula One records:

| Record | Achieved | |

|---|---|---|

| Most consecutive fastest laps | 7 | 1952 Belgian Grand Prix - 1953 Argentine Grand Prix |

| Highest percentage of fastest laps in a season | 75% (1952, 6 out of 8) | 1952 Formula One season |

| Most consecutive laps in the lead | 304 | 1952 Belgian Grand Prix - 1952 Dutch Grand Prix |

| Most consecutive distance led | 1.3 K mile (2.08 K km) | 1952 Belgian Grand Prix - 1952 Dutch Grand Prix |

| Most consecutive hat-tricks | 4 | 1952 German Grand Prix - 1953 Argentine Grand Prix |

| Most grand slams in a season | 3 (1952) | 1952 German Grand Prix - 1952 Dutch Grand Prix |

| Most consecutive grand slams | 2 | 1952 German Grand Prix - 1952 Dutch Grand Prix |

| Highest percentage of possible championship points in a season | 100% (1952, 36 out of 36) | 1952 Formula One season |