1. Early life and background

Mario Andretti's early life was marked by displacement and hardship in post-World War II Italy, before his family's eventual emigration to the United States, where he would later become a citizen and begin his legendary racing career.

1.1. Childhood in Italy

Mario Gabriele Andretti was born on February 28, 1940, in Montona, Istria, Kingdom of Italy (present-day Motovun, Croatia). He was born six hours before his twin brother, Aldo Andretti. His father, Alvise "Gigi" Andretti, worked as a farm administrator, and his mother was Rina. He also had an older sister, Anna Maria Andretti Burley. The Andretti family owned a 2,100-acre farm in Montona.

After World War II, the 1947 Treaty of Paris transferred the territory to communist-controlled Yugoslavia. As a result, the Andretti family joined the Istrian-Dalmatian exodus in 1948, losing all their land and being permitted to take only one truckload of possessions. They spent seven years in a refugee camp in Lucca, Italy, living in an abandoned college dormitory without running water.

The Andretti twins developed an interest in racing at an early age. At five, they raced hand-crafted wooden cars through the streets of Montona. After moving to Lucca, the brothers found work parking cars at a local garage. Andretti recalled in his autobiography, "The first time I fired up a car, felt the engine shudder and the wheel come to life in my hands, I was hooked. It was a feeling I can't describe. I still get it every time I get into a race car." The garage owners, noticing their passion, took them to watch the 1954 Mille Miglia, won by two-time Formula One champion Alberto Ascari. Ascari became Andretti's personal idol. The twins also visited Monza for the 1954 Italian Grand Prix, where Andretti saw Ascari race against Juan Manuel Fangio. Although they didn't have grandstand seats, Andretti remembered "being just mesmerized, overwhelmed by the sound, by the speed."

1.2. Move to the United States

After a three-year wait for U.S. visas, the Andretti family immigrated to the United States in 1955. They arrived in New York Harbor on June 16, after an eleven-day journey on the SS Conte Biancamano, with just 125 USD in cash. They settled in Nazareth, Pennsylvania, where Alvise Andretti's brother-in-law, Tony, lived. Although Alvise initially planned to return to Italy after five years, the family remained in the United States.

Mario initially opposed leaving Italy. His father believed moving to America would offer his children the best opportunities, but he strongly opposed his sons becoming motor racers due to the extreme dangers of the sport at the time. Andretti, who initially planned to become a welder, described racing as "the only passion [he] really had career wise" and admitted he might not have become a racer had he stayed in Italy. His father did not watch him race until Mario reached IndyCar in 1964. Andretti initially claimed to have become a naturalized U.S. citizen on April 15, 1964, but later revealed his naturalization certificate was issued on April 7, 1965.

2. Early racing career

Mario Andretti's racing journey began on dirt tracks with his brother Aldo, quickly establishing him as a formidable competitor before his progression into single-seater open-wheel racing.

2.1. Debut in dirt track racing

The first car Andretti regularly drove was his father's 1957 Chevrolet, which the twins modified with features like a glasspack muffler and fuel injection, though they did not race it. The brothers were surprised to discover that Nazareth hosted a half-mile dirt track, Nazareth Speedway. They used money earned working at their uncle's Sunoco station to refurbish a 1948 Hudson Super Six, even using a stolen beer barrel as a fuel tank. They prepared the car when they were 19, but the minimum racing age was 21. They convinced a newspaper editor to falsify their driver's licenses. After Aldo was involved in a serious accident, the local police chief noticed the forgery but overlooked it to ensure Aldo's health insurance coverage.

The twins did not inform their father about their racing until Aldo fractured his skull in a race and spent 62 days in a coma. Mario's father nearly disowned him when he insisted on racing again, but eventually relented. Aldo also resumed racing but suffered a career-ending accident in 1969.

The twins found immediate success, each winning two of their first four sportsman races. In their first two weeks, they earned 300 USD, significantly more than their previous 45 USD per week at the gas station. From 1960 to 1961, Mario won 21 out of 46 modified stock car races. The twins raced against each other only once, at Oswego Speedway in 1967, where Mario won and Aldo finished tenth due to brake failure. To intimidate opponents, the twins bought Italian racing suits and fabricated a story about racing in junior formulae back in Italy. Andretti maintained this fiction for many years, admitting in 2016 that it "psych[ed] [the opponents] out, big time."

2.2. Single-seater racing

Despite his early success in modified stock cars, Andretti's ambition was to compete in single-seater open-wheel cars. He began racing midget cars in the American Racing Drivers Club (ARDC) series from 1961 to 1963, progressing from 3/4-sized midgets to full-sized ones. In March 1962, he secured a midget race victory, which he called "my first victory of any consequence." In 1963, he participated in over one hundred events, achieving 29 top-five finishes in 46 ARDC races and ultimately finishing third in the season standings. On Labor Day in 1963, Andretti won three feature races at two different tracks-an afternoon race at Flemington and a doubleheader at Hatfield. After this impressive performance, reporter Chris Economaki told him, "you just bought the ticket to the big time."

The next step in East Coast racing was sprint car racing, first with the United Racing Club (URC) series and then with the United States Auto Club (USAC) series. Andretti struggled to secure a full-time URC ride, receiving only spot starts. However, USAC team owner Rufus Gray offered him a full-time drive for 1964. He won one race at Salem and finished third in the season standings, behind veterans Don Branson and Jud Larson. To cover his expenses, he also worked as a foreman at a golf cart factory.

Andretti continued sprint car racing even after moving to IndyCar. In 1965, he won at Ascot Park and finished tenth in the season standings. In 1966, he secured five victories at various tracks but finished second in the standings to Roger McCluskey. In 1967, he won two of the three events he entered.

3. Professional racing career

Mario Andretti's professional racing career spanned several decades and disciplines, marking him as one of motorsport's most versatile and successful figures.

3.1. USAC IndyCar career

From 1956 to 1978, the premier open-wheel racing series in North America was the USAC National Championship, also known as IndyCar or Champ Car. In 1971, USAC separated its dirt-track races into a distinct National Dirt Car Championship, later rebranded as the "Silver Crown Series", while the pavement championship retained the name USAC Championship Car Series.

3.1.1. Breaking in (1964)

Andretti made his IndyCar debut during the 1964 season while still actively competing in sprint cars. On April 19, 1964, the Doug Stearly team gave him a spot start at the 1964 Trenton 100, where he started 16th and finished 11th.

He spent the initial part of the 1964 season seeking a full-time IndyCar position. A potential opportunity arose with Dean Van Lines Racing Division (DVL), one of IndyCar's top three teams, after their driver Chuck Hulse was injured. Andretti met with DVL's chief mechanic, Clint Brawner, seeking the drive. Despite an introduction from his sprint car team owner, Rufus Gray, Brawner initially turned him down, skeptical of sprint car racing and believing Andretti was not yet ready. DVL instead hired Bob Mathouser as Hulse's replacement. Andretti subsequently joined Lee Glessner's team but was unable to compete in the 1964 Indianapolis 500.

3.1.2. Dean Van Lines, Andretti Racing, and STP (1964-1971)

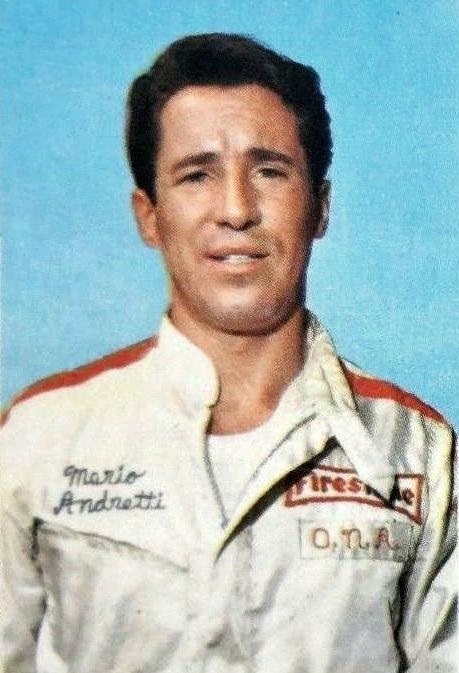

Andretti's significant breakthrough came midway through the 1964 season with DVL. He impressed Brawner in two races: a sprint car race in Terre Haute, Indiana, and an IndyCar race at Langhorne Speedway, where Andretti finished ninth, just three places behind Mathouser, despite driving an inferior car. Brawner, who had previously mentored a young A. J. Foyt, observed that Andretti "worked as diligently on the car as Foyt had as a rookie with me." Andretti was eager to join what he considered one of the "few outfits worth driving for." He completed the final eight races of the season with DVL, finishing 11th in the season standings and earning the IndyCar Rookie of the Year award. Following the season, Brawner confirmed Andretti as his permanent driver.

The Andretti-Brawner partnership quickly dominated the sport, attracting technical and financial support from Firestone and Ford, leading Brawner to describe DVL as a works team. From 1965 to 1969, Andretti won three USAC IndyCar titles, narrowly missing five consecutive championships by just 93 points. At his statistical peak, Andretti won 29 of 85 USAC championship races between 1966 and 1969.

In 1965, his first full season with DVL, Andretti utilized the team's new Brawner Hawk, a derivative of the Brabham Formula One chassis. His third-place finish at the 1965 Indianapolis 500 earned him the race's Rookie of the Year award. He secured his first IndyCar race victory at the Hoosier Grand Prix. Although he won only one race that year, he achieved six second-place and three third-place finishes, scoring points in 16 of 18 races. His closest competitor, A. J. Foyt, who had won four of the previous five USAC titles, won five races but failed to score in seven. At 25, Andretti became the youngest IndyCar champion in history, a record he held for 30 years until Jacques Villeneuve's 1995 title. To his chagrin, upon appearing on Johnny Carson at the season's end, he was introduced as the Indy 500 Rookie of the Year, which he felt diminished his championship win.

In 1966, Andretti clinched his second consecutive USAC title. Unlike his first championship, he won eight of fifteen starts and led 1,142 laps, almost 1,000 more than his nearest competitor. He led 54.5% of all laps that year, a record until Al Unser's 66.8% in 1970, and still the second-highest figure as of the 2022 season. Andretti also secured pole position at the 1966 Indianapolis 500 but retired after 27 laps due to mechanical failure.

In 1967, Andretti lost the USAC championship to A. J. Foyt. Despite winning eight races, Foyt's victory at the 1967 Indianapolis 500 proved decisive. Andretti was on pole at Indianapolis but lost a wheel during the race. He also battled through broken ribs to remain in the title hunt. Foyt held a 340-point lead over Andretti entering the season-ending Rex Mays 300 at Riverside. Andretti ran out of fuel with four laps remaining, settling for third, which cost him 180 points. Foyt's tire sponsor, Goodyear, arranged for him to take over Roger McCluskey's car to prevent Andretti, a Firestone driver, from winning. Foyt piloted McCluskey's car to fifth place, and despite a point deduction, he won the championship by 80 points. Andretti received his first Driver of the Year award but was disappointed by the outcome, stating, "I had the championship in my hands, and then it was gone."

DVL owner Al Dean died at the end of the 1967 season, leading to the team's dissolution as per his wishes. The estate sold the team's assets to Andretti, who became an owner-driver under the name Andretti Racing Enterprises. Brawner remained as chief mechanic. In 1968, Andretti again lost the title in the final race at Riverside, but in a reversal of 1967's events. He held a 304-point lead over Bobby Unser and at one point led Unser by 47 seconds on track. However, his engine failed on lap 58. He then borrowed Joe Leonard's car (whose brakes had failed) and later Lloyd Ruby's car for the final stretch. He fought back to third, but only laps completed in Ruby's car counted, yielding him just 165 points instead of the usual 420. Unser finished second, scoring 480 points, and won the title by 11 points, the narrowest margin in USAC history. Despite losing the championship, Andretti set standing records for second-place finishes in a season (11 times in 27 starts) and podium finishes (16).

| # | Season | Date | Sanction | Track / Race | No. | Winning Driver | Chassis | Engine | Tire | Grid | Laps Led |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 1968 | August 4 | USAC | Circuit Mont-Tremblant Heat 1 | 2 | Mario Andretti | Hawk III | Ford Indy DOHC V8 | Firestone | Pole | 26 |

| 2 | August 4 | USAC | Circuit Mont-Tremblant Heat 2 | 2 | Mario Andretti (2) | Hawk III | Ford Indy DOHC V8 | Firestone | Pole | 38 | |

| 3 | September 2 | USAC | DuQuoin | 2 | Mario Andretti (3) | Kuzma 60 D | Offenhauser L4 252 cu | Firestone | 6 | 94 | |

| 4 | September 22 | USAC | Trenton International Speedway | 2 | Mario Andretti (4) | Hawk II | Offenhauser L4 TC 168 cu | Firestone | 2 | 172 |

Unhappy with being an owner-driver and concerned about Firestone's sponsorship budget reductions, Andretti sold his team to Andy Granatelli's STP Corporation before the 1969 season. Granatelli retained the DVL cars and staff, though Brawner, who disliked Granatelli, insisted on not participating in racing decisions. Andretti won nine races in 1969, including the 1969 Indianapolis 500 and the Pikes Peak International Hill Climb. He secured his third title and was named ABC's Wide World of Sports Athlete of the Year. His 5,025 points were a USAC record, nearly double runner-up Al Unser's 2,630. His IndyCar prize money of 365.17 K USD (including a 205.73 K USD check for the Indianapolis 500 win) was, by some accounts, the largest single-season haul in American sports history at that point, with his total earnings, including endorsements, estimated at up to 1.00 M USD.

The core team disbanded after the 1969 championship season when Goodyear convinced STP mechanics Clint Brawner and Jim McGee to form their own team. Andretti remained with STP, which agreed to sponsor him in a privateer March for the 1970 Formula One season. Various reasons were cited for the split. Brawner stated that he and McGee left due to underpayment by Granatelli and Firestone, and that his traditional approach clashed with Andretti and McGee's desire for innovation. He was particularly upset that Andretti wanted to replace the old Brawner Hawk with a chassis from Team Lotus. However, rumors also suggested Andretti forced Brawner out, which Andretti denied. In his foreword to Brawner's 1975 autobiography, Andretti wrote that "we had our disagreements, but until things started turning sour near the end, we worked them out," adding that "racing relationships are like Hollywood marriages: they seldom last long." McGee observed that Andretti and Brawner had been "feuding for years," but "certainly respected each other," and believed Brawner was unwilling to work for Granatelli. An urban legend arose that Brawner's wife, Kay, cursed the Andretti family after the STP split, contributing to the "Andretti curse."

Neither party fully recovered from the split. The Brawner/McGee team's financial backer went bankrupt, and McGee returned to STP in 1971. Meanwhile, Andretti finished fifth in the 1970 USAC Championship Car season, and the STP Formula One team closed after one season. In the 1971 USAC Championship Car season, Andretti dropped to ninth in the paved track championship and scored no points in the dirt track standings, with a best finish of 13th.

3.1.3. Parnelli (1972-1975)

For the 1972 season, Andretti left STP and joined Vel's Parnelli Jones Racing. Parnelli was the dominant team in IndyCar at the time, with champions like Al Unser (1970) and Joe Leonard (1971). Andretti convinced the team to hire Lotus designer Maurice Philippe, and Jim McGee also joined. This combination was widely anticipated to be a "superteam."

However, Andretti never won an IndyCar title with Parnelli. In his three full-time IndyCar seasons with the team (1972-1974), he finished 11th, 5th, and 14th, while his teammate Leonard secured the 1972 USAC Championship Car title. Andretti achieved better results on dirt tracks, winning the 1974 title after taking three out of five races. He nearly won the 1973 title as well, but teammate Al Unser edged him out despite Andretti winning two of three races.

During this period, Andretti became increasingly interested in formula racing. He made guest appearances in Formula One with Ferrari in 1972 and competed in Formula 5000 in 1974 and 1975. In both Formula 5000 seasons, he finished second to Brian Redman, winning as many races as Redman but with less consistent results. In 1975, Andretti stopped competing full-time in IndyCar to focus on a full-time Formula One drive with the Parnelli team. After Parnelli withdrew from Formula One in early 1976, they released Andretti from his USAC contract so he could continue focusing on Formula One.

3.1.4. Penske (1976-1978)

While racing with Team Lotus, Andretti made sporadic appearances in IndyCar with McGee's new team, Penske Racing. In nineteen races from 1976 to 1978, he secured one victory at Trenton in 1978 and achieved eight top-five finishes.

3.1.5. Indianapolis 500 performances

Andretti participated in the Indianapolis 500 29 times, securing only one victory despite three pole positions and seven top-three grid placements. He completed the full 500 mile distance only five times and famously quipped that "if it had been the Indy 400, I'd have had at least six" victories. He experienced so many incidents and near-wins at the track that critics refer to a phenomenon known as "the Andretti curse."

Andretti did achieve some notable successes at Indianapolis. He won the 1969 race under fortunate circumstances: he completed the event in the team's backup car, an already outdated Brawner Hawk, and on a single set of tires. His race engineer later revealed that the Hawk's gearbox was failing and would not have lasted another five laps. Andretti was also the first driver to exceed 200 mph during practice for the 1977 race.

However, starting in 1981, Andretti encountered several extraordinary instances of bad luck at the Indianapolis 500. In 1981, he controversially lost the win after Bobby Unser passed cars under caution. In 1985, he finished second to Danny Sullivan, who miraculously spun without crashing but recovered to win. In 1987, he led 170 of the first 177 laps but ironically caused his engine to fail by slowing down to preserve it. In 1992, he broke six toes, his son Jeff broke both legs, and his son Michael lost a 28-second lead with 12 laps remaining due to mechanical failure. Finally, in his last serious chance at a win in 1993, he led the most laps but his race was derailed after the team incorrectly changed the tire stagger on his car during a late pit stop. Additionally, in 2003, at age 63, Andretti tested the injured Tony Kanaan's car at Indianapolis, but was involved in a "spectacular" airborne crash after Kenny Bräck crashed in front of him, though he escaped with only minor injuries. Reflecting on the "curse" in 2019, Andretti noted that while he "think[s] about all the times [he] should have won here," he also won in 1969 "when everything went wrong."

3.2. Stock car racing career

At the peak of his IndyCar career, Andretti also made thirty appearances in top-level stock car racing from 1965 to 1969. Alongside A. J. Foyt, he is one of only two drivers to win NASCAR's most prestigious race, the Daytona 500, without being a full-time stock car driver.

In USAC stock car racing, Andretti achieved one win and eight top-five finishes in sixteen races from 1965 to 1968. His best season was 1967, when he competed in eight of 22 races, won round 12 at Mosport, and finished seventh in the standings.

In the NASCAR Grand National Series, Andretti was less consistently successful, with one win, one top-five finish, and three top tens in fourteen races from 1966 to 1969. He primarily drove for the Ford works team, Holman-Moody, securing the drive through his connections at Ford headquarters. He generally did not receive the best equipment or pit crews, and noted that a lack of technical support forced him to seek advice from rookie Donnie Allison for car setup. After convincing the team to provide him with a top-spec engine, he won the 1967 Daytona 500. However, he later alleged that the team attempted to sabotage his race to ensure their lead driver, Fred Lorenzen, would win. His friend Parnelli Jones corroborated this accusation. Andretti ceased competing in NASCAR after 1969, as race seats with top-tier teams like Holman-Moody rarely became available after the 1960s.

In the 1970s and 1980s, Andretti competed in six editions of the International Race of Champions (IROC), an invitational stock car series with a limited schedule. He won IROC VI (1979) and finished second in IROC III (1976) and IROC V (1978). Overall, he won three races in twenty events.

3.3. Formula One career

Mario Andretti's Formula One career saw him transition from part-time roles to a World Championship victory, primarily with Team Lotus.

3.3.1. Part-time roles (1968-1970)

Although the Indianapolis 500 was removed from the Formula One calendar in 1960, some teams, including Colin Chapman's Team Lotus, continued to race at Indianapolis. At the 1965 Indianapolis 500, Lotus star Jim Clark won, and Andretti finished third as the top-placed rookie. Based on Clark's recommendation, Chapman invited Andretti to race in Formula One, telling him, "When you're ready, call me."

Andretti joined Lotus for the 1968 Italian Grand Prix. He was impressed by the Lotus 49B, citing its handling as a significant improvement over IndyCar. He broke the Monza lap record in testing, but was disqualified after returning to America for a contractually obligated race. He later claimed that Monza officials had promised to waive the rule on his behalf.

Andretti's true Formula One debut came at the 1968 United States Grand Prix, where he immediately took pole position. Due to his disqualification at Monza (where he had qualified tenth), he became the first Formula One driver to start his first race from pole. Jackie Stewart overtook him on the first lap, but they raced closely until Andretti's nose cone broke, forcing him to pit. He eventually retired with a clutch failure, but he made a strong impression. A Motor Sport review noted that Andretti displayed "that same assurance of absolute control [in the corners] one saw in [Jim] Clark's driving."

"It's my neck. I put it under the guillotine every time I climb into a race car. So if somebody puts a price on it, I am going to study the sales tag-very carefully."

- Mario Andretti, What's it Like Out There?

At the end of the 1968 season, Chapman offered Andretti a full-time drive to replace Clark, who had died in an accident that April. Andretti declined, unwilling to abandon his stable USAC career. For the next two years, he made only sporadic appearances in Formula One with Lotus and STP-March. These cars were largely uncompetitive, and he finished only one race in his first three seasons. In that race, the 1970 Spanish Grand Prix, he secured his first Formula One podium after several drivers ahead of him retired due to mechanical issues.

3.3.2. Ferrari (1971-1972)

Andretti signed with Scuderia Ferrari for the 1971 season, competing in seven of 11 races and finishing two. In his Ferrari debut, he won his maiden Grand Prix at 1971 Kyalami after race leader Denny Hulme's engine failed with four laps remaining. He also won the non-championship 1971 Questor Grand Prix in California. Following the Questor win, Enzo Ferrari offered Andretti the role of his No. 1 driver for 1972, but Andretti declined, later commenting that "[Formula One] didn't pay much back then [...] but I always figured I'd get another opportunity." Andretti also raced five times in 1972 but achieved no podium finishes. He did not compete in the 1973 Formula One season.

3.3.3. Parnelli (1974-1976)

In the mid-1970s, Andretti encouraged Parnelli, his IndyCar team, to sponsor a Formula One car. To prepare for this Formula One challenge, the team secured funding from Firestone, which agreed to produce custom tires. In addition to Maurice Philippe, the team recruited more Lotus veterans, including Jim Clark's former crew chief Dick Scammell and administrator Andrew Ferguson.

Parnelli entered Andretti in the two North American end-of-season races in 1974. He qualified third at the 1974 United States Grand Prix but did not start the race due to mechanical failure. Parnelli also fielded Andretti in the North American Formula 5000 series in 1974 and 1975, where he finished second to Brian Redman both times. In each season, Andretti matched Redman's win count but lacked consistency in his results.

In 1975, Andretti became a full-time Formula One driver for the first time. He was disappointed with the Parnelli VPJ4, which he felt was derivative of the Lotus 72. More significantly, sponsor Viceroy withdrew before the season, impacting the VPJ4's performance as it had been designed for Firestone's custom tires. The car also frequently suffered from brake failures. At the 1975 Spanish Grand Prix, Andretti qualified fourth and briefly led after a multi-car crash on the first lap, but damage to his suspension forced his eventual retirement. He finished third at the non-championship 1975 BRDC International Trophy Race. At the 1975 Swedish Grand Prix, he narrowly avoided a fatal crash when his brakes failed during qualifying, but he recovered to finish fourth with the team's backup car. He finished 14th in the Drivers' Championship with five points.

Parnelli skipped the first race of the 1976 season, so Andretti started the year with Lotus before returning to Parnelli for the next two races. Parnelli withdrew from Formula One after round three when sponsor Viceroy pulled its funding. Andretti learned of the decision from a reporter as the grid was lining up for the race start. He later admitted that "I was the only one, really, that wanted [the Formula One team]."

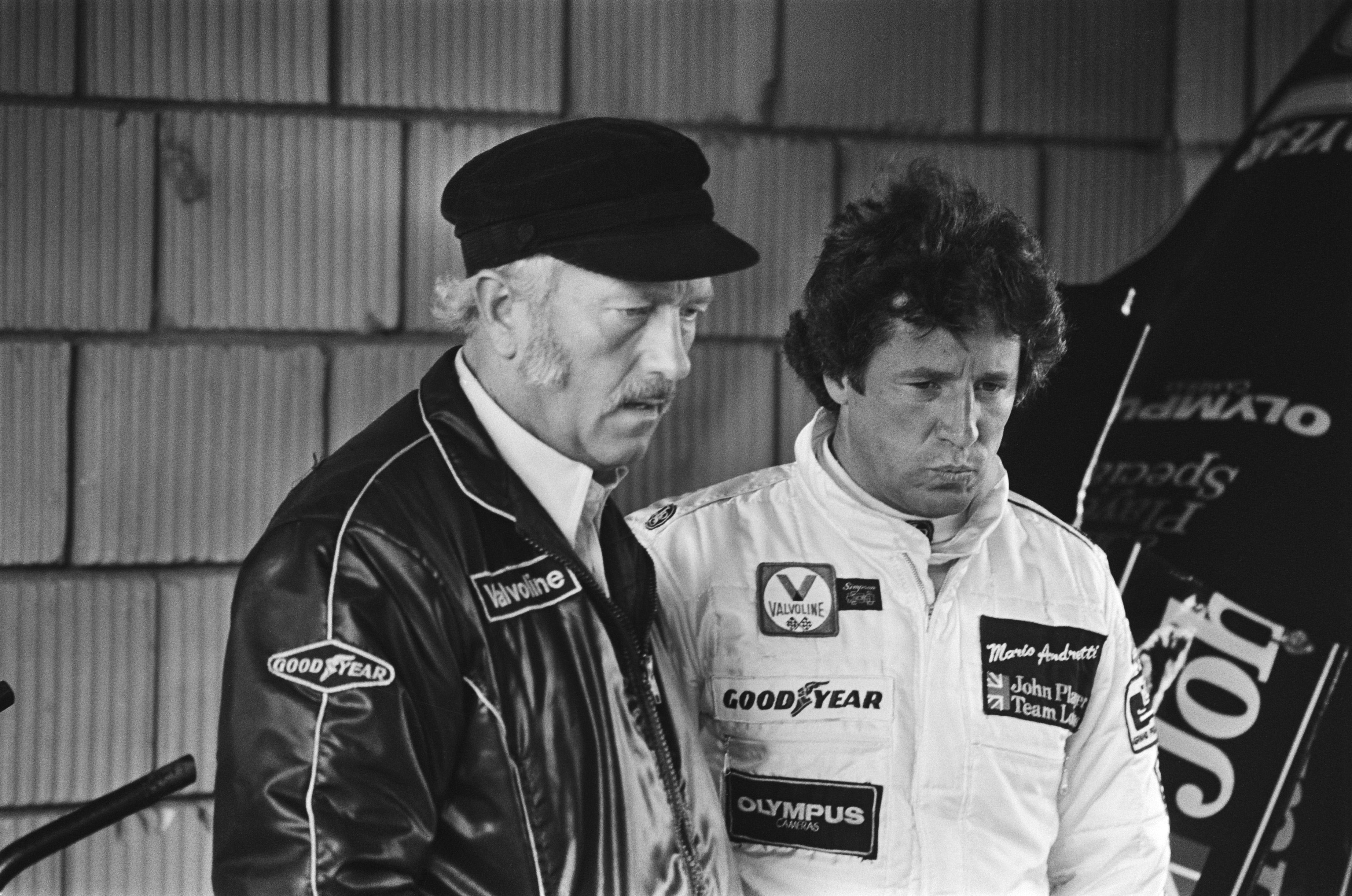

3.3.4. Lotus (1976-1980)

The day after learning of Parnelli's shutdown, Andretti met Colin Chapman of Lotus, who told him, "I wish I had a decent car for you." Andretti accepted the Lotus offer, promising Chapman, "we will make the car better." He negotiated for number one driver status, aware of Chapman's reputation for giving preferential equipment to only one driver. This authority allowed him to use his teammate's car if it proved faster on a particular circuit or when his own car was unavailable.

The Lotus 77 was uncompetitive, and with five races remaining, Andretti had only scored five points, placing him 13th. He requested to switch to the following year's car mid-season, but Chapman declined. At the 1976 Dutch Grand Prix, Andretti earned his first podium since March 1971. He collected three podiums in the final five races and lapped the field in his victory at the season-ending 1976 Japanese Grand Prix. This late-season surge moved Andretti to sixth in the Drivers' Championship with 22 points.

3.3.5. Alfa Romeo (1981)

For the 1981 Formula One season, Andretti chose between Alfa Romeo and McLaren. He opted for the Italian team due to his friendship with one of their engineers and a more attractive salary offer. Before the 1981 season, the FIA outlawed sliding sideskirts, which the Alfa Romeo design team had relied upon to generate ground effect. Andretti finished fourth in his debut at the 1981 United States Grand Prix West, but the team was otherwise uncompetitive. He finished 17th in the Drivers' Championship with three points. He left the team after the season, explaining that the new generation of Formula One cars required "toggle switch driving with no need for any kind of delicacy [...] it made leaving Formula One a lot easier than it would have been."

3.3.6. Stand-in appearances (1982)

During the 1982 season, Andretti made brief appearances for both the Drivers' and Constructors' Championship-winning teams, Williams and Ferrari. Andretti joined Williams for the 1982 United States Grand Prix West after Reutemann abruptly retired. He damaged his suspension after contacting a wall and retired from the race. IndyCar commitments prevented him from signing a full-time contract with Williams, whose driver Keke Rosberg went on to win the Drivers' Championship.

Andretti then replaced the injured Didier Pironi at Ferrari for the final two races of the season. He secured pole position and finished third at the 1982 Italian Grand Prix. In his final Formula One race, the season-ending 1982 Caesars Palace Grand Prix, Andretti retired with a suspension failure, but Niki Lauda's engine failure clinched the Constructors' Championship for Ferrari. Andretti agreed to serve as Renault's reserve driver for one U.S. race in 1984 but declined consideration for a reserve role in 1986, effectively ending his Formula One career.

3.4. CART IndyCar career

After his Formula One career, Mario Andretti returned to full-time American open-wheel racing under the Championship Auto Racing Teams (CART) sanctioning body, achieving further success and records.

3.4.1. Penske (1979-1980)

In 1979, Championship Auto Racing Teams (CART) established the IndyCar World Series, which eventually replaced the USAC championship. CART was formed by larger, more established IndyCar teams, including Andretti's Penske Racing, who sought to emphasize technical innovation (despite the high costs) and a more structured commercial strategy. After Penske helped found CART, Andretti competed sporadically in CART during the 1979 and 1980 seasons, securing one victory at Michigan in 1980.

3.4.2. Patrick (1981-1982)

Andretti moved to Patrick Racing for the 1981 season, a move that reunited him with the team's sponsor, STP Corporation, and his former mechanic, Jim McGee. Although he did not win a race, he recorded five top-five finishes in seven starts, with his other two results being mechanical retirements. At the 1981 Indianapolis 500, Andretti was controversially stripped of the win four months after the race. After leaving Alfa Romeo, Andretti joined CART full-time for the 1982 season. He finished third in the season standings, achieving six podiums in 11 races. As in 1981, all his non-podium finishes were mechanical retirements.

3.4.3. Newman/Haas (1983-1994)

In 1983, Andretti joined the newly formed Newman/Haas Racing team, co-founded by Carl Haas and actor (and former Can-Am team owner) Paul Newman. The team utilized cars built by the British company Lola, in contrast to the then-popular March cars. Newman/Haas attracted Andretti by promising a single-car operation, making him the sole focus of the team. Andretti remained with Newman/Haas for the rest of his full-time racing career.

3.5. Sportscar racing career

Mario Andretti demonstrated his versatility by competing extensively in sportscar endurance racing, achieving significant victories, though a win at Le Mans eluded him.

3.5.1. North American endurance racing

Andretti's first sportscar race was in 1965, driving a Ferrari 275 P at the Bridgehampton 500 km at Bridgehampton, where he did not finish. He went on to win the 12 Hours of Sebring endurance race three times (1967, 1970, 1972) and a 6-hour race at Daytona in 1972. In his early sportscar career, he competed for Holman-Moody, but later frequently drove for Ferrari.

Andretti signed with Ferrari in 1971 and won several races with co-driver Jacky Ickx. In 1972, he shared victories in all three North American rounds of the championship and at Brands Hatch in the UK, contributing to Ferrari's dominant victory in that year's World Championship for Makes. He also competed in 25 North American Can-Am races in the late 1960s and early 1970s, with his best finish being third place at Riverside in 1969.

3.5.2. Le Mans

Andretti competed in the 24 Hours of Le Mans across four decades. In 1966, he co-drove a Holman-Moody Ford Mk II with Lucien Bianchi but retired due to valve failure. In 1967, during a pit stop at 3:30 AM, a mechanic mistakenly installed a front brake pad backward, causing Andretti's brakes to lock up at the Dunlop Bridge. He crashed, breaking several ribs, and was left exposed to oncoming traffic until Roger McCluskey pulled him to safety.

Andretti did not return to Le Mans until after ending his full-time Formula One career. In 1982, he partnered with his son Michael in a Mirage M12 Ford. They qualified ninth, but despite passing initial inspection days earlier, their car was disqualified shortly before the race due to an improper oil cooler. They returned the following year (1983) and finished third in a Porsche customer car, behind two works Porsches. The Andrettis returned in 1988 with Mario's nephew John joining the family team. Although they had a factory Porsche 962, one of the car's engine cylinders failed, and the team finished fifth.

Following his retirement from full-time racing, Andretti decided to pursue another Le Mans victory, joining Courage Compétition from 1995 to 1997. In 1995, the team qualified third, but Andretti was brake-checked by the car ahead and crashed, forcing a pit stop that cost the team six laps. The team ultimately rallied from 25th to second overall and finished first in the LMP1 class. Andretti later stated that the team "lost [the 1995] race five times over" due to poor organization, including a botched pit stop, an ill-advised switch to wet-weather tires, and a two-minute pit stop to wash the car for sponsor decals. Porsche withdrew active support from Courage in 1996, and the team finished 16th after losing 90 minutes in the pits fixing an electronic issue and a broken axle. In 1997, the "now ancient Courage" was a backmarker, and the team did not finish the race. Andretti's final appearance at Le Mans was in 2000, six years after his full-time retirement. At 60 years old, Andretti drove the Panoz LMP-1 Roadster-S to a 15th-place finish.

4. Legacy and influence

Mario Andretti's legacy is defined by his unique achievements, widespread impact on motorsports, and enduring presence in popular culture.

4.1. Unique distinctions and records

Over the course of his extensive career, Andretti won over 100 races on major circuits, with exact figures varying slightly by definition (e.g., 109 or 111). His name has become synonymous with speed in American popular culture. An exceptionally versatile driver, Andretti holds unique or near-unique distinctions across multiple racing categories:

- He is the only driver to win the Indianapolis 500 (1969), Daytona 500 (1967), and the Formula One World Drivers' Championship (1978).

- He is one of only two drivers (the other being Dan Gurney) to have won races in Formula One, IndyCar, the World Sportscar Championship, and NASCAR.

- He is one of only three drivers to have won major races on road courses, paved ovals, and dirt tracks in a single season, a feat he accomplished four times.

With his final IndyCar win in April 1993, Andretti became the first driver to have won IndyCar races in four different decades and the first to win automobile races of any kind in five. As of 2024, Andretti's victory at the 1978 Dutch Grand Prix remains the most recent Formula One win by an American driver.

4.2. Awards and honors

| Competition | Wins |

|---|---|

| American Championship Car (IndyCar) | 52 |

| USAC Silver Crown Series | 5 |

| Formula One | 12 |

| F1 Non-Championship | 1 |

| Formula 5000 | 7 |

| Sports car | 7 |

| Stock car | 2 |

| IROC | 3 |

| USAC Sprint Car | 9 |

| Midget Car | 9 |

| 3/4 Midget Car | 4 |

Andretti was recognized as Driver of the Century by the Associated Press (1999) and RACER magazine (2000). In 1992, he was voted the U.S. Driver of the Quarter Century by a panel of journalists and former U.S. Drivers of the Year. He received the U.S. Driver of the Year award in 1967, 1978, and 1984, making him the only driver to receive the honor in three different decades.

He has been inducted into numerous motorsports halls of fame, including the International Motorsports Hall of Fame (2000), the Indianapolis Motor Speedway Hall of Fame (1986), the Motorsports Hall of Fame of America (1990), the U.S. National Sprint Car Hall of Fame (1996), the Automotive Hall of Fame (2005), the USAC Hall of Fame (2012), the FIA Hall of Fame (2017), and the U.S. National Midget Auto Racing Hall of Fame (2019).

Several race tracks have named areas after Andretti, such as "The Andretti" (the final turn of the Circuit of the Americas), the "Andretti Hairpin" (turn 2 at Laguna Seca), and the "Andretti Road" (the grandstand driveway at Pocono). In 2019, a section of a street in Indianapolis was renamed "Mario Andretti Drive" to commemorate the 50th anniversary of his 1969 Indianapolis 500 win. His former home street in Nazareth, Pennsylvania, was renamed "Victory Lane" after his Indianapolis 500 triumph.

In 2003, the Champ Car World Series race at Road America was renamed the "Mario Andretti Grand Prix" after he helped broker a deal to keep it on the CCWS calendar. Andretti has also been honored by the Vince Lombardi Cancer Foundation (2007) and the Simeone Foundation (2008).

On October 23, 2006, the Italian government bestowed upon Andretti the title of Commendatore of the Order of Merit of the Italian Republic (OMRI), Italy's most senior order of merit, in recognition of his racing career and dedication to his Italian heritage. In 2008, Andretti was also named honorary mayor of an association of Italian exiles from his birthplace of Montona. Other accolades include the Carnegie Corporation's Great Immigrants Award (2006, inaugural class), the Italy-USA Foundation's America Award (2015), and honorary citizenship of Lucca, Italy (2016). In 2004, he served as the grand marshal of the New York City Columbus Day Parade.

4.3. Public perception and cultural impact

Mario Andretti's name became synonymous with speed in American popular culture, similar to how Barney Oldfield was in the early 20th century and Stirling Moss in the United Kingdom. His sustained success across diverse motorsport disciplines, including his unique achievement of winning the Indianapolis 500, Daytona 500, and the Formula One World Championship, cemented his iconic status.

5. Personal life

Mario Andretti's personal life reflects his deep family ties, particularly his enduring racing legacy, and his successful transition into business endeavors.

5.1. Andretti racing family

Andretti resides in Bushkill Township, Pennsylvania, a suburb of Nazareth, on an estate he named "Villa Montona" in homage to his birthplace. His late wife, Dee Ann (née Hoch), was a Nazareth native. They met in 1961 when she was teaching him English and married on November 25, 1961. They had three children-Michael, Jeff, and Barbara-and seven grandchildren. Dee Ann passed away on July 2, 2018, following a heart attack.

Both of Mario Andretti's sons, Michael and Jeff, became auto racers. Michael joined CART in 1983, won the 1991 title, and finished second on five occasions. He was named U.S. Driver of the Year in 1991 and was third on the all-time IndyCar career wins list at the time of his retirement. Jeff Andretti competed in CART from 1990 to 1994. Mario's nephew, John Andretti, competed in CART and NASCAR, winning one CART race in 1991 and two NASCAR races (1997 and 1999). Additionally, in 2006, Mario's grandson Marco earned the Indy Racing League Rookie of the Year award and the Indianapolis 500 Rookie of the Year Award, following in the footsteps of Mario, Michael, and Jeff.

During the 1991 CART season, the Andrettis made history as the first family to have four relatives compete in the same series. The Andrettis have also competed together in endurance racing: Mario, Michael, and John finished sixth at the 1988 24 Hours of Le Mans, and Mario, Michael, and Jeff finished fifth at the 1991 Rolex 24 at Daytona.

The Andretti family's history at the Indianapolis 500 is marked by a notable phenomenon often referred to as the "Andretti Curse." Despite frequent strong performances, including pole positions and leading many laps, numerous mechanical failures, accidents, and unusual circumstances have often prevented family members from securing victory. While Mario himself won the race in 1969, his sons Michael and Jeff, nephew John, and grandson Marco have all experienced frustrating near-misses and bad luck, failing to add another Indy 500 win to the family's extensive racing record, in stark contrast to families like the Unsers who have multiple victories. A memorable instance occurred in 2006 when Marco and Michael were running first and second in the final stages of the 500-mile race, only for both to be passed by Sam Hornish Jr. in the final laps, finishing second and third respectively.

5.2. Business and post-racing activities

After his retirement, Andretti remained actively involved in the racing community. He serves on the board of the Cadillac Formula One team, which is set to join Formula One in 2026. Since 2012, Andretti has been the official ambassador for the Circuit of the Americas (COTA) and the United States Grand Prix. In the media, Andretti test-drives cars for Road & Track and Car and Driver magazines and has written a racing column for the Indianapolis Star. He also participated in the 2006 Bullrun Rally from New York to Los Angeles.

Andretti's business ventures extend beyond racing. Upon his retirement at age 54, his personal fortune was estimated at 100.00 M USD. In 1995, Andretti and Joe Antonini revitalized a struggling Napa Valley vineyard, renaming it the Andretti Winery. Andretti was interviewed about his winemaking activities for the documentary A State of Vine (2007). In 1997, he established Andretti Petroleum, which owns a chain of gasoline stations and car washes in Northern California. He also owns a chain of go-kart tracks. He was the title character of several video games, including Mario Andretti's Racing Challenge (1991), Mario Andretti Racing (1994), and Andretti Racing (1996/1997), the latter developed in collaboration with his sons.

6. Media appearances

Andretti has made notable appearances in various media, often associated with racing, and lent his voice to animated characters.

He contributed to and partially narrated The Speed Merchants (1972), a documentary about the 1972 World Sportscar Championship, in which his Ferrari won the constructors' championship. He also drove an IndyCar in the IMAX film Super Speedway (1996). He appeared in the documentary Dust to Glory (2005), which covers a race where he served as grand marshal. In November 2015, he was featured on the first season of the TV series Jay Leno's Garage, driving Leno in various high-performance cars and discussing his racing career.

Andretti has also made cameo or guest appearances in other media, typically with racing connections. Like many other IndyCar drivers, he guested on the television show Home Improvement. He made a cameo in Bobby Deerfield (1977), and voiced a sentient version of the Ford Fairlane (the car he won the 1967 Daytona 500 in) in Pixar's animated film Cars (2006). He also voiced the traffic director at Indianapolis Motor Speedway in DreamWorks' animated film Turbo (2013). Andretti is also mentioned in Amy Grant's 1991 hit song "Good For Me".

7. Criticism and controversies

Mario Andretti has faced occasional criticism and been involved in public controversies, notably regarding alleged team sabotage and his outspoken remarks on various topics.

He famously alleged that his Holman-Moody NASCAR team attempted to sabotage his car during the 1967 Daytona 500 so that their lead driver, Fred Lorenzen, could win, an accusation supported by his friend Parnelli Jones.

Andretti is known for his candid and often blunt public statements. In 1982, after colliding with Kevin Cogan's Penske car and retiring early from the Indianapolis 500, Andretti expressed his fury in an interview, stating that the incident was "the result of letting children drive."

More recently, Andretti has been critical of certain movements in Formula One. While acknowledging Lewis Hamilton's efforts on social issues, he has also criticized Hamilton for "bringing politics into F1" and being "presumptuous." He questioned the effectiveness of Mercedes-AMG F1 painting their car black, stating, "I don't know what good that does." He also commented on NASCAR driver Bubba Wallace's incident, stating that what appeared to be a noose in his garage "looked like a terrible situation, but in reality, it was nothing of the sort," suggesting it was "political thinking." These remarks drew criticism, with Hamilton noting that "it's certainly true that some older generations are stuck in their ways and are unable to acknowledge it."

8. Racing record

8.1. Racing career summary

| Competition | Wins |

|---|---|

| American Championship Car (IndyCar) | 52 |

| USAC Silver Crown Series | 5 |

| Formula One | 12 |

| F1 Non-Championship | 1 |

| Formula 5000 | 7 |

| Sports car | 7 |

| Stock car | 2 |

| IROC | 3 |

| USAC Sprint Car | 9 |

| Midget Car | 9 |

| 3/4 Midget Car | 4 |

9. External links

- [https://www.marioandretti.com/ Official website]