1. Overview

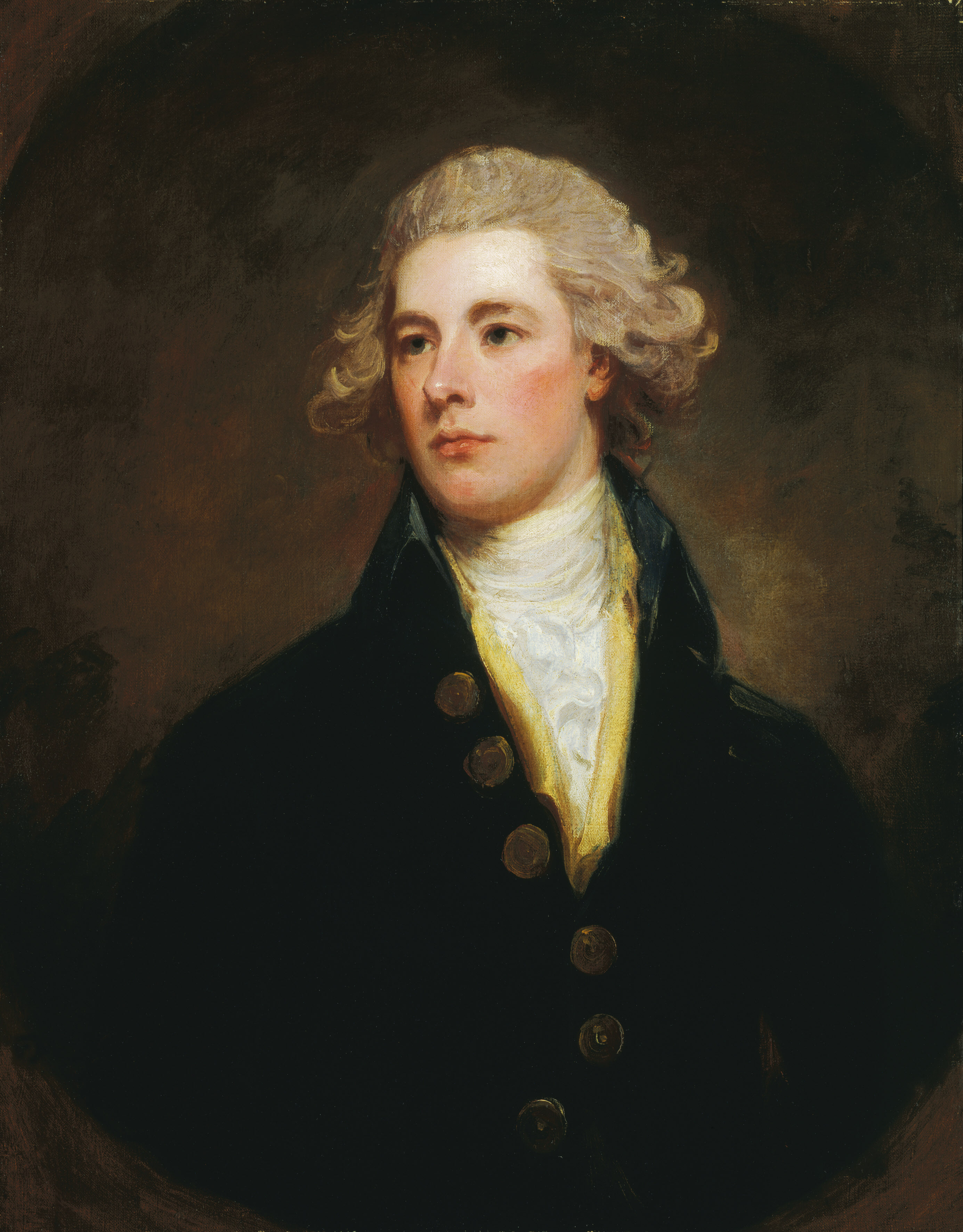

William Henry Cavendish Cavendish-Bentinck, 3rd Duke of Portland (14 April 1738 - 30 October 1809) was a prominent British politician who served as Prime Minister of Great Britain in 1783 and as Prime Minister of the United Kingdom from 1807 to 1809. His political career spanned the tumultuous late Georgian era, marked by the American Revolutionary War and the French Revolution, which significantly shaped his ideological evolution from a Whig to an alignment with the Tory party. Portland's two terms as prime minister were separated by 24 or 26 years, the longest such gap for any British prime minister. Beyond his premierships, he held several key cabinet positions, including Home Secretary and Lord President of the Council, and exerted considerable influence over parliamentary elections through his extensive estates and patronage. His legacy is complex, reflecting both his contributions to the stability of British governance and the conservative policies he adopted in response to revolutionary fervor, which had implications for social and democratic progress. He was also an ancestor of Queen Elizabeth The Queen Mother and Charles III.

2. Early Life and Education

William Cavendish-Bentinck's foundational years were shaped by his aristocratic birth, a comprehensive education, and extensive travel, which prepared him for a life in public service.

2.1. Birth and Family Background

William Henry, Lord Titchfield, was born on 14 April 1738 at Bulstrode Park in Buckinghamshire. He was the eldest son of William Bentinck, 2nd Duke of Portland and Lady Margaret Cavendish-Harley, who was described as "the richest woman in Great Britain". Through his mother and his maternal grandmother, Henrietta Cavendish-Holles, the only daughter of John Holles, 1st Duke of Newcastle, he inherited vast lands. In 1755, while studying at Oxford University, he added "Cavendish" to his surname based on Henrietta's will, though this change was formally approved by the King only on 5 October 1801. Before succeeding to the Dukedom in 1762, he was known by the courtesy title Marquess of Titchfield. He eventually held a title for every degree of British nobility: Duke (Portland), Marquess (Titchfield), Earl (Portland), Viscount (Woodstock), and Baron (Cirencester).

2.2. Education and Grand Tour

Portland received his early education at Westminster School from 1747 to 1754. He then matriculated at Christ Church, Oxford, on 4 March 1755, graduating with a Master of Arts degree on 1 February 1757.

In December 1757, at the age of nineteen, Lord Titchfield embarked on a Grand Tour under the tutelage of Lord Stormont in Warsaw, accompanied by Stormont's secretary, Benjamin Langlois. Stormont was responsible for overseeing his expenditures, while Langlois directed his studies, recommending ancient history, modern history, and general law. In 1759, Titchfield continued his travels with Langlois through Germany to Italy, spending a year in Turin before proceeding to Florence. He returned to Britain in October 1761.

3. Marriage and Children

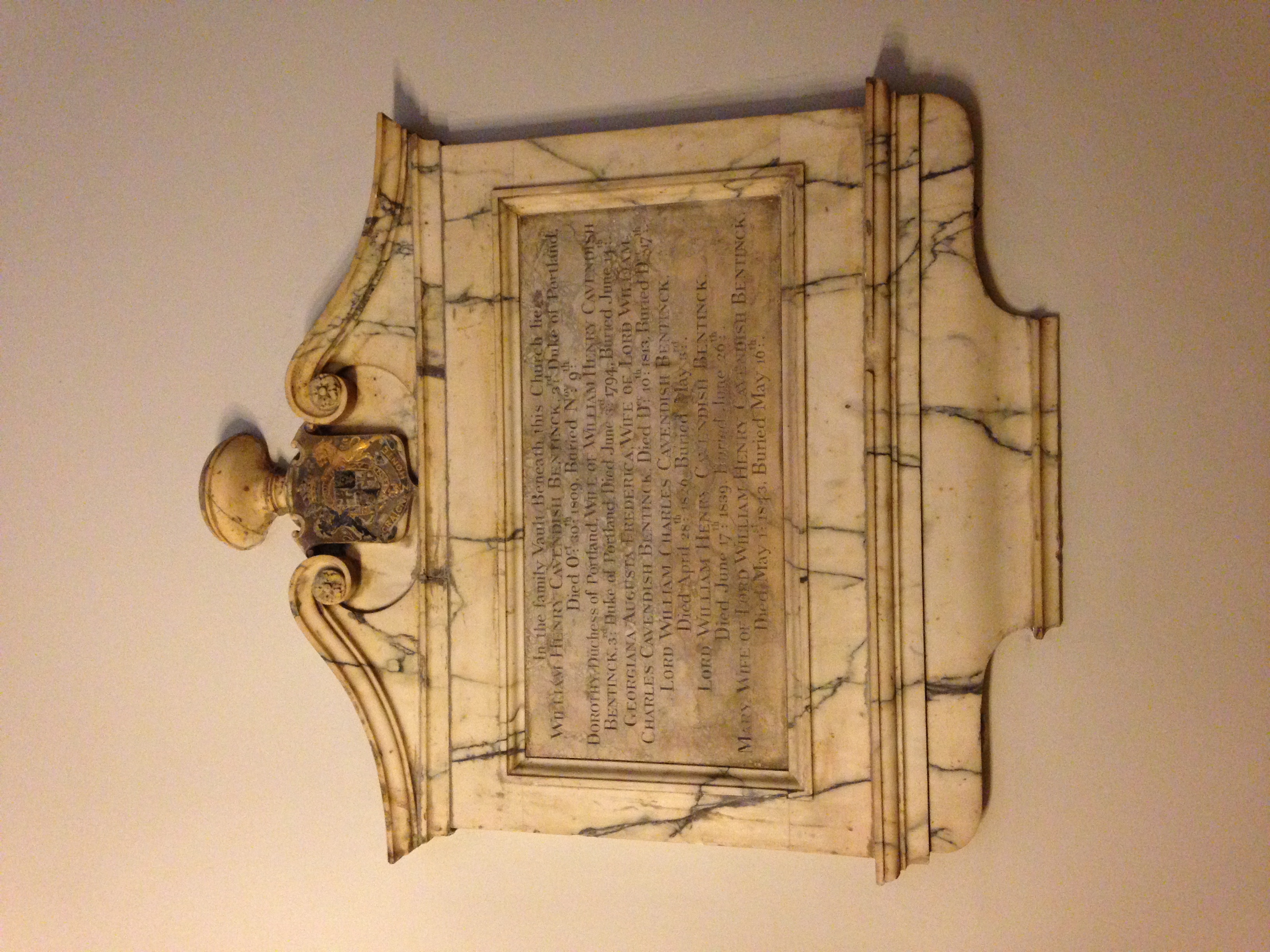

On 8 November 1766, Portland married Lady Dorothy Cavendish (27 August 1750 - 3 June 1794), the only daughter of William Cavendish, 4th Duke of Devonshire and Lady Charlotte Boyle. They had nine children, six of whom survived to adulthood:

- William Henry Cavendish-Scott-Bentinck, 4th Duke of Portland (24 June 1768 - 27 March 1854)

- Lord William Henry Cavendish-Bentinck (14 September 1774 - 17 June 1839), who served as Governor-General of India. He married Mary Acheson (died 1 May 1843), daughter of Arthur Acheson, 1st Earl of Gosford, on 19 February 1803.

- Lady Charlotte Cavendish-Bentinck (2 October 1775 - 28 July 1862), who married Charles Greville (2 November 1762 - 26 August 1832) on 31 March 1793, and had children.

- Lady Mary Cavendish-Bentinck (13 March 1779 - 6 November 1843)

- Lord William Charles Augustus Cavendish-Bentinck (20 May 1780 - 28 April 1826), an ancestor of the 6th Duke of Portland and Queen Elizabeth The Queen Mother. He married Georgiana Augusta Frederica Seymour (died 10 December 1813) on 21 September 1808, and had one daughter. He remarried Anne Abdy (died 19 March 1875), former wife of Sir William Abdy, 7th Baronet, and illegitimate daughter of Richard Wellesley, 1st Marquess Wellesley, on 23 July 1816, and had children.

- Lord Frederick Cavendish-Bentinck (2 November 1781 - 11 February 1828), an ancestor of the 8th and 9th Duke of Portland. He married Mary Lowther, daughter of William Lowther, 1st Earl of Lonsdale, on 16 September 1820, and had children.

4. Political Career

The Duke of Portland's political career was extensive and marked by shifting alliances, reflecting the turbulent political landscape of late 18th and early 19th century Britain.

4.1. Entry into Parliament

Portland was elected to the Parliament of Great Britain for the constituency of Weobley in 1761. His tenure in the House of Commons was brief; he succeeded his father as Duke of Portland on 1 May 1762, which elevated him to the House of Lords. During his short time as a Member of Parliament, there are no recorded votes or speeches.

4.2. Early Political Activities

Despite his youth, Portland, with his considerable wealth and unblemished reputation, was welcomed by various factions of the Whig Party. He aligned himself with the aristocratic Whig faction led by Lord Rockingham (known as the Rockingham Whigs).

In July 1765, when the First Rockingham Ministry was formed, Portland was appointed Lord Chamberlain of the Household and became a Privy Councillor on 10 July 1765. On 5 June 1766, he was elected a Fellow of the Royal Society. Following the fall of Rockingham's ministry in March 1766, Portland initially intended to resign. However, he was persuaded to remain as an intermediary between the Rockingham Whigs and the new Prime Minister, William Pitt, 1st Earl of Chatham. When negotiations failed in November, Portland, along with a small number of peers, resigned from office. This experience led him to develop a strong dislike for Chatham and to commit fully to the Rockingham faction. He subsequently refused to accept any ceremonial or powerless government positions, such as Lord Chamberlain.

As an opposition figure, Portland became a fierce critic of Augustus FitzRoy, 3rd Duke of Grafton, the First Lord of the Treasury. His strong opposition led to speculation that he was the anonymous writer "Junius," though the Dictionary of National Biography dismissed this as "absurd." The Rockingham Whigs' insistence that Rockingham should be prime minister, even in a coalition, kept them in opposition for an extended period, but it also strengthened the cohesion of their faction.

4.2.1. Lord Lieutenant of Ireland

Portland served as Lord Lieutenant of Ireland in Rockingham's Second Rockingham Ministry from April to August 1782. His appointment came at a critical juncture, immediately after Britain's defeat in the American Revolutionary War. The Irish Patriot Party seized the opportunity to demand greater autonomy for Ireland. Portland recognized that refusing these demands was impossible and sought to secure some concessions for Great Britain in return for granting autonomy. However, his efforts were undermined by Lord Shelburne, the Home Secretary, and George III, who sought to prevent the Rockingham faction from gaining too much power within the cabinet. Consequently, concessions were made to Ireland, including the repeal of the Declaratory Act 1719 and modifications to Poynings' Law, without any reciprocal benefits for Great Britain. Following Rockingham's death in July 1782, Portland resigned from Shelburne's ministry along with other supporters of Charles James Fox.

4.3. First Premiership (1783)

After Shelburne's resignation, a coalition government was formed in April 1783, known as the Fox-North coalition, with Portland serving as the nominal Prime Minister and First Lord of the Treasury. The true leaders of this administration were Charles James Fox (Foreign Secretary) and Lord North (Home Secretary). The formation of this coalition, despite the prior animosity between the Rockingham and North factions, was partly due to Portland's persuasion that their policy differences had vanished with the end of the American Revolutionary War.

During his brief tenure, the Treaty of Paris (1783) was signed, formally ending the American Revolutionary War. The only other significant policy initiative was Fox's East India Company reform bill. Although it passed the House of Commons by a large margin, it was defeated in the House of Lords on 17 December 1783, after George III made it known that any peer voting for the measure would be considered his personal enemy. The King dismissed the coalition ministry the following day.

The widespread defeat of the coalition's supporters in the 1784 British general election highlighted the unpopularity of Fox, North, and Portland. However, the collapse of the ministry also cast Portland as a victim of political maneuvering, making his return to the premiership an essential condition for the Whig Party's resurgence.

4.4. Political Realignment and Key Cabinet Roles

Following the fall of his first government, William Pitt the Younger was appointed Prime Minister. Portland assumed leadership of the Rockingham Whig faction. While not a gifted orator, Portland possessed the reliability, high social standing, and wealth that had characterized Rockingham. However, he proved to be a weak opposition leader, often leaving parliamentary tactics to Fox and Edmund Burke while he focused on his life at Bulstrode Park and his musical hobbies. He also had strained relations with the radical wing of his party, opposing electoral reform and the repeal of the Test Act.

4.4.1. Shift to Pitt's Government

The outbreak of the French Revolution in 1789 initially elicited sympathy from Portland, Pitt, and Fox. However, as the revolution became more radical, Portland, like other large landowners, grew fearful of its spread to Britain. The Whig Party itself began to fracture, notably with Burke's criticism of Fox in May 1791 and the establishment of the reform-oriented Society of the Friends of the People in April 1792. Pitt attempted to negotiate with Portland, using Lord Loughborough as an intermediary, to separate Portland from Fox. However, Portland insisted on Fox's inclusion in any coalition, complicating negotiations. Pitt's duplicity was exposed when Francis Osborne, 5th Duke of Leeds, in July-August 1792, sounded out George III about a Pitt-Fox coalition with himself as nominal prime minister, and the King stated he had instructed his cabinet to only offer "flattering gestures" to the opposition Whigs.

Despite Pitt's failed attempts, the French Revolution continued to deepen divisions within the Whig Party. In December 1792, Sir Gilbert Elliot prematurely announced a break between Portland and Fox over Fox's recognition of the French Republic, an announcement he retracted days later as it was made without Portland's permission. While Portland was ideologically conservative, he delayed a definitive break with Fox until January 1794 to consolidate his faction, successfully doubling the number of Portland Whigs from 28 in 1793 to 60 in 1794. However, this Portland faction dissolved during the coalition with Pitt.

During his time in opposition, Portland consistently refused government favors, including an offer of the Order of the Garter. However, on 27 September 1792, he was elected Chancellor of the University of Oxford and received an honorary Doctor of Civil Law degree on 7 October of the same year.

4.4.2. Home Secretary

With the Portland faction becoming a significant force, Pitt was compelled to change course. In July 1794, Portland was appointed Home Secretary. His appointment was further recognized with the award of the Order of the Garter on 16 July 1794, and he was named Lord Lieutenant of Nottinghamshire in June 1795. His eldest son, Marquess of Titchfield, was also appointed Lord Lieutenant of Middlesex.

Portland's tenure as Home Secretary coincided with the enactment of measures such as the Aliens Act 1793, the Treason Act 1795, and the Seditious Meetings Act 1795, which significantly expanded the Home Secretary's discretionary powers. Historian H. Morse Stephens praised Portland's administration, noting that he did not abuse his powers and avoided bringing disrepute to the government. Stephens contrasted this with the later tenure of Henry Addington as Home Secretary (1812-1822), which saw events like the Peterloo Massacre (1819) and the Cato Street Conspiracy.

In Irish affairs, Portland's period as Home Secretary saw major events, including the Irish Rebellion of 1798 and the passage of the Acts of Union 1800. The Act of Union, which aimed to merge the Kingdom of Ireland with the Kingdom of Great Britain, was initially defeated in 1799. To ensure its passage in 1800, Portland oversaw a widespread campaign of bribery within the Irish Parliament. Between October 1799 and May 1800, 30.85 K GBP was sent from Great Britain to Ireland for this purpose, an action that violated the Civil List Act in both countries. He continued to serve in the cabinet until Pitt's death in 1806.

4.4.3. Lord President of the Council

When Pitt resigned in 1801 over the issue of Catholic Emancipation, Portland, despite his own views on Irish Catholic subsidies, remained in the cabinet after being persuaded by George III and Pitt's successor, Henry Addington. He was appointed Lord President of the Council in July 1801, a position he held until 1805.

However, with the outbreak of the Napoleonic Wars in 1803, Portland felt that the weak Addington should be replaced by Pitt as Prime Minister. Pitt subsequently formed his Second Pitt ministry in 1804. Pitt attempted to form a broad coalition, including Portland, Fox, and Lord Grenville, but George III refused to allow Fox into the cabinet, forcing Pitt to form a government on a weaker, narrower basis. Portland continued as Lord President of the Council and welcomed George III's refusal to include Fox.

Portland's eldest son, the Marquess of Titchfield, became close to George Canning through his wife, Henrietta, whose sister Joan was Canning's wife. As Canning was a strong supporter of Pitt, Titchfield followed suit. This influenced Portland to also support Pitt. In 1805, when Pitt sought to bring Addington into the cabinet, Portland even ceded his position as Lord President of the Council to Addington, becoming a Minister without Portfolio until 1806.

4.4.4. Minister without Portfolio

After Pitt's death in office in 1806, William Grenville formed the Ministry of All the Talents. Portland retired from government and withdrew to Bulstrode Park.

4.5. Second Premiership (1807-1809)

By 1806, Portland was nearly 70 years old and suffered from gout, desiring a peaceful retirement. However, the collapse of the "Ministry of All the Talents" created a vacuum, and Pitt's former supporters sought to return to power. Portland was seen as an acceptable figurehead to lead a fractious group of ministers, including strong personalities like George Canning and Lord Castlereagh. His good relationship with George III and his reputation as a supporter of Pitt, despite his Whig background, made him a suitable candidate to lead a Tory government. He was appointed Prime Minister again in March 1807.

Given his advanced age and ill health, Portland was not suited for the demanding role of Prime Minister. In practice, power was largely wielded by Canning (Foreign Secretary) and Castlereagh (Secretary of State for War and the Colonies), while Spencer Perceval (Chancellor of the Exchequer) handled the day-to-day duties of the First Lord of the Treasury.

Portland's second government oversaw significant developments in the Napoleonic Wars, though he was not personally responsible for their outcomes. These included the victory at the Battle of Copenhagen in 1807, the disastrous Walcheren Campaign in 1809, and key events in the Peninsular War such as the Battle of Vimeiro (August 1808), the Convention of Cintra (August 1808), and the Battle of Talavera (July 1809).

A deep animosity existed between Canning and Castlereagh. When Canning threatened to resign unless Castlereagh was dismissed, Portland initially agreed but then hesitated, delaying the decision. This internal conflict eventually came to a head when Castlereagh discovered Canning's negotiations, leading to a duel between them. Both resigned from the cabinet, which ultimately forced Portland's own resignation.

4.6. Electoral Influence and Patronage

Unlike his father, the 3rd Duke of Portland actively engaged in electoral politics. For instance, in the 1768 British general election, he successfully secured the election of eight candidates from his faction.

4.6.1. Wigan Constituency

The borough constituency of Wigan in Lancashire had approximately 100 voters. In 1761, Whigs Fletcher Norton and Simon Luttrell had just wrested control of the constituency from the Tories. While small enough to be considered a rotten borough, it was not easily controlled by a single patron, and Norton and Luttrell did not secure universal support. Portland allied with George Byng, who had lost to Norton in a 1763 by-election, gaining the support of a segment of the electorate. In the 1764 mayoral election, Portland's faction declared their candidate elected, while Norton and Luttrell also declared their own candidate. This resulted in two parallel mayoralties until a settlement was reached in May 1765, where Norton and Luttrell's mayor stepped down in exchange for financial compensation.

In the subsequent 1768 British general election, Portland's candidates, Byng and Beaumont Hotham, defeated the Tory candidate, John Smith Barry. They were re-elected in the 1774 British general election. As Portland reduced his electoral activities in the 1780s, he ceded control of one Wigan seat to Henry Bridgeman, whose son, Henry Simpson Bridgeman, was elected in the 1780 British general election. Although Portland retained some influence in Wigan, Bridgeman was considered to control both seats by the 1790s.

4.6.2. Carlisle Constituency

The Carlisle constituency in Cumberland was historically contested by the Howard (Earls of Carlisle), Musgrave, and Lowther families. When Portland inherited his title, Sir James Lowther, 5th Baronet (later 1st Earl of Lonsdale), controlled one seat and sought to control the other. Lowther, who married the daughter of John Stuart, 3rd Earl of Bute, a Tory, in 1761, had steadily increased his influence in Carlisle. He had served as Lord Lieutenant of Cumberland since 1759 and had placed his allies in positions within the Carlisle magistracy and corporation.

Unable to break Lowther's control over the corporation, Portland appealed to the freemen. Lowther's misstep in the 1768 British general election of endorsing two Scottish candidates, John Eliot and George Johnstone, who had no ties to Carlisle, allowed Portland's candidates-his brother, Lord Edward Bentinck, and George Musgrave of the Musgrave family-to win both seats.

In 1769, the Howard family, led by the 5th Earl of Carlisle, Frederick Howard, sought to regain influence. In the run-up to the 1774 British general election, a compromise was initially reached in March for Portland and Lowther to each nominate one candidate. However, Carlisle delayed approving this arrangement, forcing concessions from Portland. Ultimately, Carlisle and Lowther each nominated one candidate.

In the 1780 British general election, the main branch of the Howard family, the Dukes of Norfolk, intervened over the head of the 5th Earl of Carlisle, forcing him to withdraw. Charles Howard, Earl of Surrey, was elected. After this, Portland ceased his intervention in the Carlisle constituency.

4.6.3. Cumberland and Westmorland Constituencies

In the county constituency of Cumberland, the Lowther family was the largest landowner, followed by the Earls of Carlisle, the Dukes of Portland, and the Earls of Egremont. At the time Portland inherited his title, the 5th Earl of Carlisle was a minor, and Charles Wyndham, 2nd Earl of Egremont, was an absentee landlord who had lost popularity by raising rents. Similarly, the neighboring Westmorland constituency had the fewest voters among county constituencies. While the Earls of Suffolk, the Wilson family, and the Earls of Thanet (who held the hereditary Sheriff of Westmorland office) also owned land, only the Earls of Thanet could challenge the dominant Lowther family. In a 1759 by-election, the Thanet candidate lost to Lowther's, and in the 1761 British general election, the Wilson candidate also lost to Lowther's.

However, Lowther's arrogant and self-serving demeanor alienated the local gentry in Cumberland, who chose Portland as their champion against him. Portland responded to the gentry's call, intervening in Westmorland and the Carlisle borough constituency. In retaliation, Lowther expelled Portland's supporters from the local commission of the peace in 1767.

As the 1768 British general election approached, an electoral battle in Carlisle and Cumberland became inevitable. Lowther attempted to avoid a contest in Westmorland by offering Henry Howard, 12th Earl of Suffolk, one seat in Westmorland if he could secure the support of the Egremont faction in Cumberland. However, Suffolk had already promised the Egremont faction's support to Portland, and the negotiations failed. Portland and Sackville Tufton, 8th Earl of Thanet, initially struggled to find a candidate after Wilson refused to stand again. However, just ten days before the election (28 March 1768), Thomas Fenwick, funded by Portland's faction and anti-Lowther forces in Carlisle, announced his candidacy. Despite the late entry and Thanet's neutrality (due to an electoral pact with Lowther regarding the Appleby constituency), Fenwick won the second seat with 981 votes, just two votes ahead of Lowther's third candidate, due to the unexpectedly strong anti-Lowther sentiment.

In Cumberland, Lowther's lawyers discovered a legal flaw in Portland's claim to Inglewood Forest, a territory granted by William III to the 1st Earl of Portland, arguing it remained Crown land. Lowther promptly applied to the government for a lease of Inglewood Forest, which was approved on the condition that Lowther initiate a lawsuit to confirm it as Crown land. This move was intended to give Lowther an electoral advantage, but it backfired, as locals resented the forceful seizure of land that the Portland family had held for 60 years. In national politics, Portland's opposition to the First Lord of the Treasury, the Duke of Grafton, led some to view the lawsuit as politically motivated. While the Dictionary of National Biography noted that the Crown's claim had some legal basis and was not entirely fabricated, the Oxford Dictionary of National Biography states that the government's swift approval of the lease made Portland appear as a victim of political persecution. This led to parliamentary legislation, the Nullum Tempus Act 1769, which limited the application of the legal principle "Nullum tempus occurrit regi" (no time runs against the king).

In the election, despite Lowther himself standing and being in a position to choose the returning officer, he selected an entirely unsuitable person. The result was that the anti-Lowther candidate, Henry Curwen, came first, and Lowther, with 1977 votes, was only two votes ahead of the third-place anti-Lowther candidate, Sir Henry Fletcher, who subsequently filed an election petition.

Lowther proposed a compromise to Portland twice, once just before the election in March and again in August after the election. However, Portland knew that conceding would alienate his local supporters, so negotiations failed. The House of Commons ultimately declared Fletcher elected.

When the next general election occurred in 1774, Lowther again proposed a compromise to Portland. Given the significant electoral expenses Portland had incurred, and the local population's satisfaction at having prevented Lowther from controlling both seats, a compromise was reached. From then until Lowther's death in 1802, Lowther's faction controlled one seat, and the other was held by an opposing faction. The lawsuit over the ownership of Inglewood Forest concluded in 1771 with a ruling that the lease to Lowther was invalid, and in 1777, Portland's ownership was confirmed.

5. Public Offices and Honours

Beyond his cabinet roles, Portland held several significant public and honorary positions, reflecting his broad influence and standing.

5.1. Chancellor of the University of Oxford

Portland served as Chancellor of the University of Oxford from 1792 until his death in 1809. His long tenure connected him deeply with academia and university governance.

5.2. Other Public Offices

He was the Recorder of Nottingham until his death. In 1789, Portland became one of several vice presidents of London's Foundling Hospital, a fashionable charity with a mission to care for abandoned children. His father, the 2nd Duke of Portland, had been one of its founding governors 50 years earlier. The hospital gained fame for its poignant mission, art collection, and popular benefit concerts by George Frideric Handel. In 1793, Portland succeeded Lord North as President of the Foundling Hospital, a position he held until his death. He was also appointed Lord Lieutenant of Nottinghamshire in 1795, serving until 1809.

6. Personal Life and Finances

Portland's personal life was characterized by a grand lifestyle and considerable financial challenges despite his vast inheritance.

6.1. Estate and Financial Affairs

Upon his marriage in 1766, Portland's income from his estates was approximately 9.00 K GBP annually, with 1.60 K GBP allocated to his mother. Following his mother's death in 1785, he inherited additional lands, increasing his annual income to about 12.00 K GBP. These inherited estates included Welbeck Abbey in Nottinghamshire, which comprised approximately 15 K acre (15.00 K acre). However, by the time of his death, his annual estate income had decreased to about 17.00 K GBP, and he left behind substantial debts totaling approximately 52.00 K GBP. To settle these debts, his eldest son and successor, the 4th Duke of Portland, was compelled to sell off some properties, including Bulstrode Park.

7. Death and Burial

William Cavendish-Bentinck, 3rd Duke of Portland, died on 30 October 1809 at Burlington House, Piccadilly, London. His death followed an operation for a kidney stone. He was buried on 9 November at St Marylebone Parish Church, London. He was one of eight British prime ministers to die while his direct successor was already in office, a list that includes Sir Robert Peel, Lord Aberdeen, Benjamin Disraeli, Marquess of Salisbury, Sir Henry Campbell-Bannerman, Bonar Law, and Neville Chamberlain.

8. Legacy and Evaluation

The Duke of Portland's legacy is a subject of historical assessment, considering his political evolution, administrative contributions, and the lasting impact of his actions on British society and governance.

8.1. Nomenclature and Commemoration

Several places, institutions, and items are named in his honour or associated with his life and family:

- The Portland Vase, a renowned Roman glass cameo vase, was named because it was owned by Portland and kept at his family residence, Bulstrode Park.

- Portland Parish, in Jamaica, was named after him. The Titchfield School, founded in 1786, is located in the parish and also bears his name, with its crest derived from his personal crest.

- Two major streets in Marylebone, London-Portland Place and Great Portland Street-are named after him, as they were built on land he once owned. Great Portland Street tube station, opened in 1863, takes its name from the latter.

- North Bentinck Arm and South Bentinck Arm in British Columbia, Canada, were named for the Bentinck family by George Vancouver in 1793, along with other geographical features such as Portland Canal and Portland Channel.

- Portland Bay in Victoria, Australia, was named in 1800 by the British navigator James Grant. The city of Portland is situated on this bay.

- A number of papers relating to him are held by the Manuscripts and Special Collections, The University of Nottingham. His personal and political papers (Pw F) are part of the Portland (Welbeck) Collection, and the Portland (London) Collection (Pl) contains his correspondence and official papers, particularly in series Pl C. The Portland Estate Papers at Nottinghamshire Archives also contain items related to the 3rd Duke's properties.

- The Portland Collection of fine and decorative art includes pieces owned and commissioned by him, such as paintings by George Stubbs.

8.2. Historical Assessment

H. Morse Stephens, in the Dictionary of National Biography, argued that Portland's period leading the Home Office from 1794 to 1801 should be more highly regarded than his two premierships. Stephens praised Portland for his lenient approach as Home Secretary, despite holding immense power, and noted the relatively low level of social unrest during his tenure, contrasting it with the Peterloo Massacre and Cato Street Conspiracy that occurred under Henry Addington's later term as Home Secretary (1812-1822).

The Oxford Dictionary of National Biography highlights Portland's contributions during his long period in opposition, specifically his success in elevating the social standing of the Whig Party and strengthening its organizational capabilities. However, it also describes his policies as Home Secretary as "reactionary," suggesting this was a key reason he was later chosen as a figurehead for the Tory government in his final years. His shift from Whig principles to a more conservative stance, particularly in his role overseeing the suppression of dissent and the controversial passage of the Act of Union through bribery, reflects a pragmatic adaptation to the political climate of his time, but also raises questions about his commitment to democratic development and social equity. While his administrative competence and ability to navigate complex political alliances are acknowledged, his later career is often viewed through the lens of a conservative figure who prioritized stability over radical reform in an era of revolutionary change.

9. Cabinets

9.1. First Ministry, April - December 1783

- The Duke of Portland - First Lord of the Treasury

- Lord Stormont - Lord President of the Council

- Lord Carlisle - Lord Privy Seal

- Lord North - Secretary of State for the Home Department

- Charles James Fox - Secretary of State for Foreign Affairs

- The Viscount Keppel - First Lord of the Admiralty

- Lord John Cavendish - Chancellor of the Exchequer

- The Viscount Townshend - Master-General of the Ordnance

- Lord Northington - Lord-Lieutenant of Ireland

- The Great Seal in Commission

9.2. Second Ministry, March 1807 - October 1809

- The Duke of Portland - First Lord of the Treasury

- Lord Eldon - Lord Chancellor

- Lord Camden - Lord President of the Council

- Lord Westmorland - Lord Privy Seal

- Lord Hawkesbury (after 1808, Lord Liverpool) - Secretary of State for the Home Department

- George Canning - Secretary of State for Foreign Affairs

- Lord Castlereagh - Secretary of State for War and the Colonies

- Lord Mulgrave - First Lord of the Admiralty

- Spencer Perceval - Chancellor of the Exchequer and of the Duchy of Lancaster

- Lord Chatham - Master-General of the Ordnance

- Lord Bathurst - President of the Board of Trade

;Changes

- July 1809 - Lord Harrowby, the President of the Board of Control, and Lord Granville Leveson-Gower, the Secretary at War, entered the Cabinet.

10. Arms

The heraldic achievements of the Duke of Portland are as follows:

- Crest:** Out of a ducal coronet proper, two arms counter-embowed vested Gules, on the hands gloves Or, each holding an ostrich feather Argent (Bentinck); and a snake nowed proper (Cavendish).

- Escutcheon:** Quarterly: 1st and 4th, Azure a cross moline Argent (Bentinck); 2nd and 3rd, Sable three stags' heads cabossed Argent attired Or, a crescent for difference (Cavendish).

- Supporters:** Two lions double queued, the dexter Or and the sinister sable.

- Motto:** Craignez Honte (Fear Dishonour).

The title Duke of Portland was created by George I in 1716.

11. Ancestry

William Cavendish-Bentinck, 3rd Duke of Portland, was the son of William Bentinck, 2nd Duke of Portland and Lady Margaret Cavendish Harley.

His paternal grandparents were Henry Bentinck, 1st Duke of Portland and Lady Elizabeth Noel.

His maternal grandparents were Edward Harley, 2nd Earl of Oxford and Earl Mortimer and Lady Henrietta Cavendish Holles.

His paternal great-grandparents were William Bentinck, 1st Earl of Portland and Anne Villiers, and Wriothesley Noel, 2nd Earl of Gainsborough and The Hon. Catherine Greville.

His maternal great-grandparents were Robert Harley, 1st Earl of Oxford and Earl Mortimer and Elizabeth Foley, and John Holles, 1st Duke of Newcastle and Lady Margaret Cavendish.