1. Overview

William Armstrong, 1st Baron Armstrong (1810-1900), was a preeminent English engineer, industrialist, inventor, and philanthropist who founded the **Armstrong Whitworth** manufacturing concern on Tyneside. He is widely regarded as the inventor of modern artillery, having developed the revolutionary Armstrong Gun. His pioneering work extended to hydraulic machinery, including the hydraulic crane and the weighted hydraulic accumulator, which significantly advanced industrial power transmission. Beyond his industrial achievements, Armstrong was a visionary who built Cragside, the first house in the world to be lit by hydroelectricity, demonstrating his early advocacy for renewable energy. Knighted in 1859 for surrendering his gun patents to the British government, he was elevated to the peerage as Baron Armstrong of Cragside in 1887. His extensive philanthropic contributions, including the donation of public parks and support for educational institutions, left a lasting legacy on Newcastle upon Tyne and beyond.

2. Early Life and Education

William Armstrong's early life was rooted in Newcastle upon Tyne, where he began his career in law before his profound interest in engineering led him to a transformative path.

2.1. Childhood and Family Background

William George Armstrong was born on November 26, 1810, in Newcastle upon Tyne, at 9 Pleasant Row, Shieldfield. Although the house no longer stands, an inscribed granite tablet marks its former location. The area, adjacent to the Pandon Dene, was rural at the time of his birth. His father, also named William Armstrong, was a successful corn merchant on the Newcastle quayside who ascended through the ranks of Newcastle society, eventually becoming mayor of the town in 1850. His mother, Ann, was the daughter of Addison Potter. William had an elder sister, Anne, born in 1802.

Armstrong received his early education at the Royal Grammar School, Newcastle upon Tyne, until the age of sixteen. He then continued his studies at Bishop Auckland Grammar School. During his time there, he frequently visited the nearby engineering works of William Ramshaw, where he met Ramshaw's daughter, Margaret, who was six years his senior and would later become his wife.

2.2. Legal Career

Following his father's wishes, Armstrong pursued a career in law. He was articled to Armorer Donkin, a solicitor and friend of his father's. He spent five years studying law in London, returning to Newcastle in 1833. In 1835, he became a partner in Donkin's business, and the firm was renamed Donkin, Stable and Armstrong. The same year, he married Margaret Ramshaw, and they established their home in Jesmond Dene, on the eastern edge of Newcastle. Armstrong practiced as a solicitor for eleven years, but during his spare time, he indulged his strong interest in engineering, developing the "Armstrong Hydroelectric Machine" between 1840 and 1842. In 1837, he also laid the groundwork for what is now known as Wardell Armstrong, an engineering and environmental consultancy.

3. Engineering and Invention Career

Armstrong's transition from law to engineering marked the beginning of a prolific career characterized by groundbreaking hydraulic innovations and a keen eye for practical applications.

3.1. Transition to Engineering

Armstrong's shift to engineering was sparked by an observation during a fishing trip. As a keen angler, while fishing on the River Dee at Dentdale in the Pennines, he witnessed a waterwheel powering a marble quarry. He was struck by the significant amount of wasted power. Upon his return to Newcastle, he designed a rotary engine powered by water, which was built at the High Bridge works of his friend, Henry Watson. However, this initial design garnered little interest. Undeterred, Armstrong subsequently developed a piston engine, believing it could be suitable for driving a hydraulic crane. His work as an amateur scientist gained recognition in 1846 when he was elected a Fellow of the Royal Society.

3.2. Hydraulic Innovations

In 1845, Armstrong became involved in a scheme to provide piped water to Newcastle households from distant reservoirs. He proposed to the Newcastle Corporation that the excess water pressure in the lower part of the town could be harnessed to power a specially adapted quayside crane. He asserted that his hydraulic crane could unload ships more quickly and economically than traditional cranes. The Corporation accepted his proposal, and the experimental installation proved so successful that three additional hydraulic cranes were subsequently installed on the Quayside.

The remarkable success of his hydraulic crane prompted Armstrong to consider establishing a business dedicated to manufacturing cranes and other hydraulic equipment. Consequently, he resigned from his legal practice. His legal colleague, Donkin, supported this career change, providing financial backing for the new venture. In 1847, the firm of W. G. Armstrong & Company acquired 5.5 acre (5.5 acre) of land alongside the River Tyne at Elswick, near Newcastle, and commenced construction of a factory. The new company quickly secured orders for hydraulic cranes from Edinburgh and Northern Railways and Liverpool Docks, as well as for hydraulic machinery for dock gates in Grimsby. The company expanded rapidly, producing 45 cranes in 1850 and 75 two years later, averaging 100 cranes per year for the remainder of the century. The workforce grew from over 300 men in 1850 to 3,800 by 1863. The company also diversified into bridge building, completing one of its first orders, the Inverness Bridge, in 1855.

3.3. Hydraulic Accumulator

Armstrong's contributions to hydraulic technology extended to the development of the hydraulic accumulator. In situations where sufficient water pressure was not readily available on site for hydraulic cranes, Armstrong initially constructed tall water towers to provide the necessary pressure, such as the Grimsby Dock Tower. However, when tasked with supplying cranes for use at New Holland on the Humber Estuary, this approach was impractical due to the sandy foundations. After extensive consideration, he devised the weighted accumulator. This innovative device consisted of a cast-iron cylinder fitted with a plunger that supported a very heavy weight. As the plunger was slowly raised, it would draw in water. The downward force of the weight would then be sufficient to force the water below it into pipes at high pressure. The accumulator, though perhaps unspectacular in appearance, was a highly significant invention that found numerous applications in the ensuing years, revolutionizing the efficient transmission of hydraulic power.

4. Industrial and Armaments Business

Armstrong's industrial empire saw significant growth, notably through his pioneering work in armaments, which transformed military technology and established his company as a global leader.

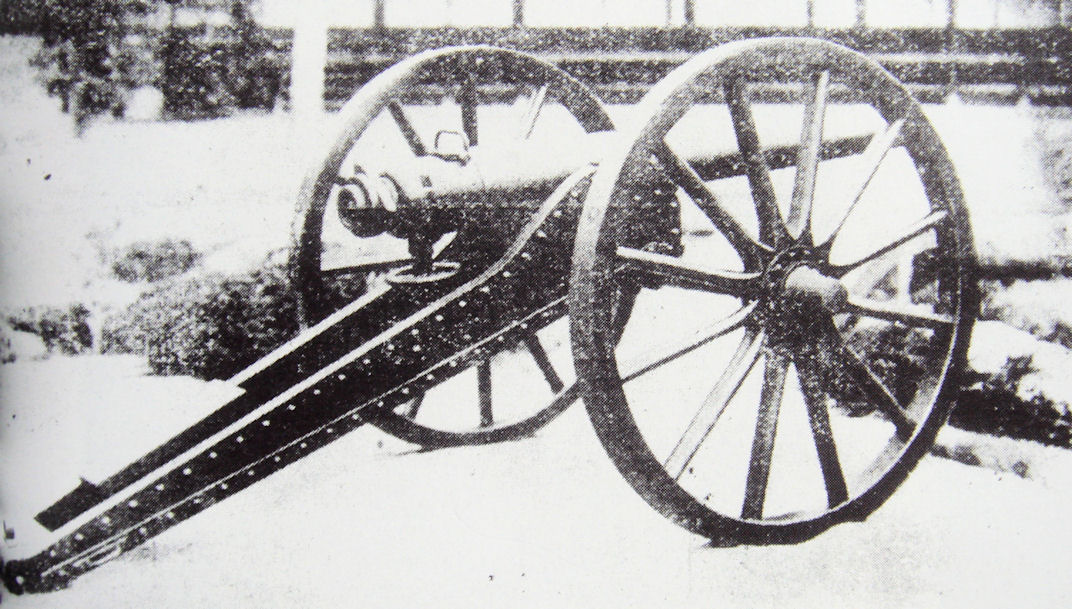

4.1. Development of the Armstrong Gun

In 1853, during the Crimean War, Armstrong received an order from the British Army to design mines. Although his design was ultimately not put into practical use, it marked Armstrong's entry into the armaments industry. In 1854, during the Crimean War, Armstrong became aware of the challenges the British Army faced in maneuvering its heavy field guns. This prompted him to design a lighter, more mobile field gun that offered greater range and accuracy. He developed a breech-loading gun with his colleague James Rendel, featuring a strong, rifled barrel constructed from wrought iron wrapped around a steel inner lining, designed to fire a shell rather than a ball. By 1855, he had a five-pounder prototype ready for government inspection. The gun performed successfully in trials, but the committee requested a higher caliber weapon, leading Armstrong to build an 18-pounder based on the same design.

Following further trials, this gun was declared superior to all its rivals. In a significant move, Armstrong surrendered the patent for the gun to the British government, choosing not to profit directly from its design. For this contribution, he was created a Knight Bachelor and was presented to Queen Victoria in 1859. Armstrong was subsequently appointed Engineer of Rifled Ordnance to the War Department. To prevent any conflict of interest, as his own company might manufacture armaments, Armstrong established a separate entity, the Elswick Ordnance Company, in which he held no financial involvement. This new company entered into an exclusive agreement to manufacture armaments solely for the British government. In his new role, Armstrong also worked to modernize the old Woolwich Arsenal to enable it to produce guns designed at Elswick.

However, the new gun soon faced considerable opposition from within the army and from rival arms manufacturers, particularly Joseph Whitworth of Manchester. Publicized criticisms claimed the gun was too difficult to use, excessively expensive, dangerous, and prone to frequent repairs. This suggested a concerted campaign against Armstrong. While Armstrong successfully refuted these claims before various government committees, the constant criticism proved exhausting. In 1862, the government decided to cease ordering the new gun and revert to muzzle-loaders. Furthermore, a drop in demand meant that future gun orders would be supplied from Woolwich, leaving Elswick without new business. Ultimately, compensation was agreed upon with the government for the loss of business, allowing the company to legitimately sell its products to foreign powers. Speculation that guns were sold to both sides in the American Civil War was unfounded. The Satsuei War in August 1863 also saw frequent barrel explosions (cavity explosions) in Armstrong guns, leading to the British military halting procurement in 1864 and the Royal Navy reverting to muzzle-loading guns. While this accident problem is sometimes cited as the reason for Armstrong's resignation, his resignation actually preceded these events.

4.2. Founding and Expansion of Elswick Works

The success of Armstrong's hydraulic cranes led to the establishment of W. G. Armstrong & Company in 1847, which acquired 5.5 acre (5.5 acre) of land at Elswick, near Newcastle, to build a factory. This marked the beginning of his industrial empire. The company rapidly expanded its production of hydraulic equipment, averaging 100 cranes per year by the mid-19th century and growing its workforce from 300 to 3,800 by 1863.

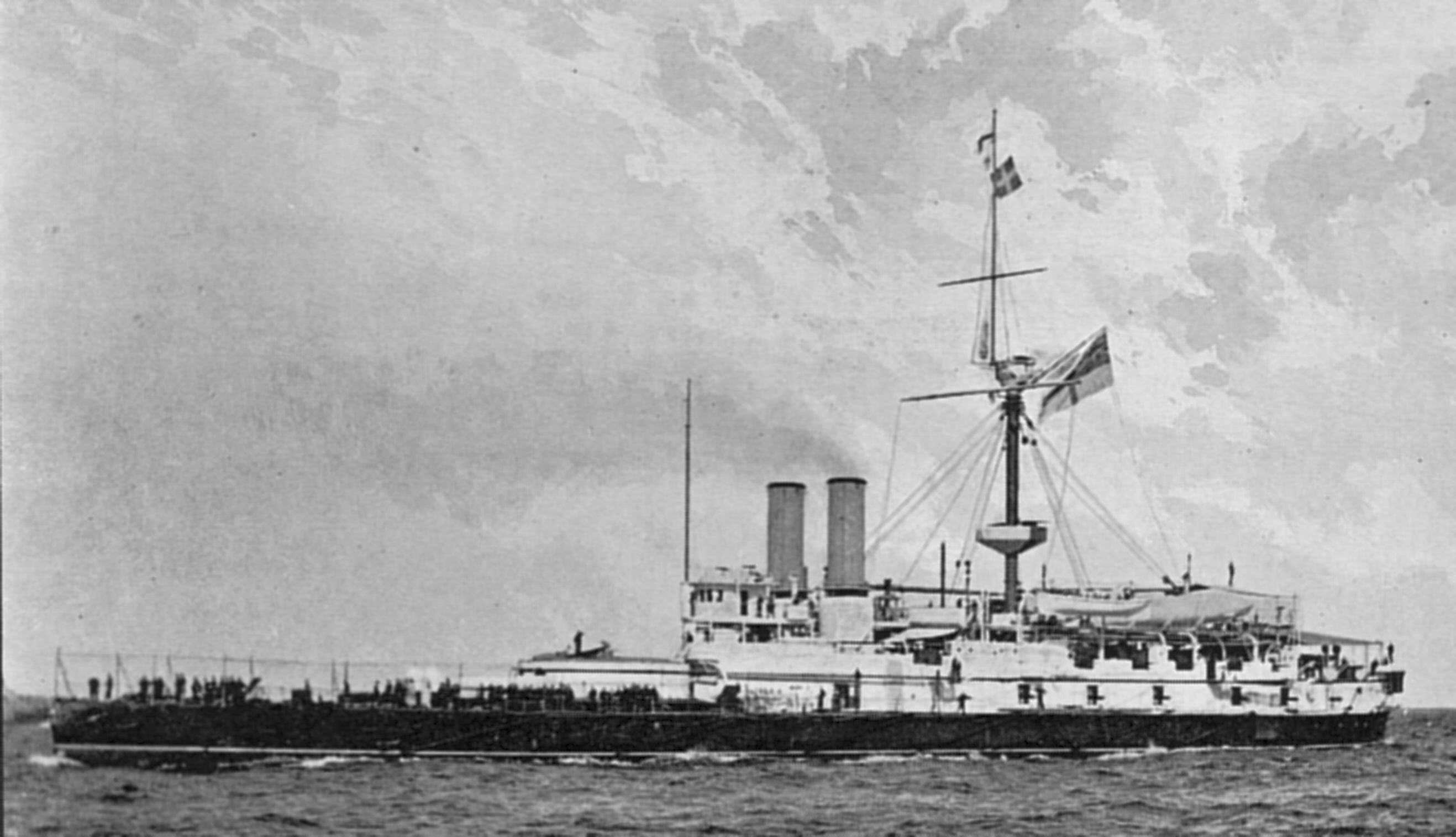

In 1864, W. G. Armstrong & Company and the Elswick Ordnance Company merged to form Sir W. G. Armstrong & Company. Armstrong had by then resigned from his position with the War Office, eliminating any conflict of interest. The newly merged company then shifted its focus to naval guns and shipbuilding. The Elswick works continued to expand, stretching for three-quarters of a mile along the riverside by 1870. This industrial growth significantly impacted the local population, with Elswick's population soaring from 3,539 in 1851 to 27,800 by 1871. In 1897, Armstrong's company merged with that of his former rival, Joseph Whitworth (who had since passed away), to form Sir W. G. Armstrong, Whitworth & Co Ltd., solidifying its position as a major industrial force.

6. Personal Life and Residence

Beyond his industrial endeavors, William Armstrong's personal life was marked by his marriage and the creation of Cragside, a groundbreaking country estate that showcased his innovative spirit.

6.1. Cragside Estate

From 1863 onwards, although Armstrong remained the head of his company, he gradually became less involved in its day-to-day operations, entrusting senior positions to capable individuals. Having acquired a house called Jesmond Dean (not to be confused with the nearby Jesmond Dene House), which is now demolished, he began to landscape and improve land he purchased within the adjacent Jesmond Dene. In 1860, he commissioned local architect John Dobson to design a Banqueting Hall overlooking the Dene, which still stands today, albeit without its roof. While his Newcastle house was convenient for his legal and industrial work, his increasing leisure time led him to desire a country residence.

Having fond memories of visiting Rothbury as a child due to a severe cough, Armstrong purchased land there in 1863. This land was situated in a steep, narrow valley where the Debdon Burn flows towards the River Coquet. He oversaw the clearing of the land and the construction of a house perched on a rock ledge overlooking the burn. He also directed an extensive program of planting trees and mosses to cover the rocky hillside with vegetation. His new house was named Cragside, and over the years, Armstrong expanded the estate significantly. Eventually, the Cragside estate encompassed 1.7 K acre (1.73 K acre), featuring seven million planted trees, five artificial lakes, and 31 mile of carriage drives, along with his demonstration center at Cragend Farm Hydraulic Silo. The artificial lakes were ingeniously utilized to generate hydroelectricity, making Cragside the first house in the world to be lit by hydroelectric power, employing incandescent lamps supplied by the inventor Joseph Swan.

As Armstrong devoted less time to the Elswick works, Cragside became his primary residence. In 1869, he commissioned the renowned architect Richard Norman Shaw to enlarge and enhance the house, a project that spanned 15 years. In 1883, Armstrong generously donated Jesmond Dene, along with its banqueting hall, to the city of Newcastle, though he retained his house adjacent to the Dene. Cragside became a venue for entertaining several distinguished guests, including the Shah of Persia, the King of Siam, the prime minister of China, and the Prince and Princess of Wales.

6.2. Family and Personal Life

William Armstrong married Margaret Ramshaw in 1835. The couple had no children. Margaret passed away in September 1893 at their house in Jesmond. William Armstrong died at Cragside on December 27, 1900, at the age of ninety. He was buried in Rothbury churchyard, alongside his wife. His heir was his great-nephew, William Watson-Armstrong, who later inherited the estate and was granted a new barony of Armstrong.

7. Later Life and Philanthropy

In his later years, William Armstrong engaged in significant public service and extensive philanthropic activities, leaving a profound mark on society and education.

7.1. Public Service and Professional Roles

In 1873, Armstrong served as High Sheriff of Northumberland. He held the presidency of the North of England Institute of Mining and Mechanical Engineers from 1872 to 1875. In December 1881, he was elected president of the Institution of Civil Engineers, serving for the subsequent year. He was also conferred with Honorary Membership of the Institution of Engineers and Shipbuilders in Scotland in 1884. In 1886, he was persuaded to stand as a Unionist Liberal candidate for Newcastle, though he was unsuccessful, coming third in the election. That same year, he was awarded the Freedom of the City of Newcastle upon Tyne. In 1887, in recognition of his contributions, he was raised to the peerage as Baron Armstrong, of Cragside in the County of Northumberland, allowing him to sit in the House of Lords. His final major project, initiated in 1894, was the acquisition and comprehensive restoration of the imposing Bamburgh Castle on the Northumberland coast, which remains in the hands of the Armstrong family.

7.2. Philanthropic Contributions

Armstrong was a notable benefactor to the city of Newcastle upon Tyne. In 1883, he generously donated the extensive wooded gorge of Jesmond Dene to the public, along with the nearby Armstrong Bridge and Armstrong Park. He played a crucial role in the establishment in 1871 of the College of Physical Science, a forerunner of the University of Newcastle, which was later renamed Armstrong College in 1906 in his honor. He served as President of the Literary and Philosophical Society of Newcastle upon Tyne from 1860 until his death and was twice president of the Institution of Mechanical Engineers. Armstrong contributed 11.50 K GBP towards the construction of Newcastle's Hancock Natural History Museum, completed in 1882. His generosity extended posthumously; in 1901, his heir, William Watson-Armstrong, donated 100.00 K GBP for the building of the new Royal Victoria Infirmary in Newcastle upon Tyne, as its original 1753 building was inadequate and could not be expanded.

8. Thought and Vision

William Armstrong's intellectual contributions extended beyond engineering to include philosophical reflections on his work and forward-thinking ideas on sustainable energy.

8.1. Views on Armaments and Responsibility

There is no evidence to suggest that Armstrong agonized over his decision to enter armament production. He once stated, "If I thought that war would be fomented, or the interests of humanity suffer, by what I have done, I would greatly regret it. I have no such apprehension." He further articulated his perspective by saying: "It is our province, as engineers to make the forces of matter obedient to the will of man; those who use the means we supply must be responsible for their legitimate application." While some sources attribute the "fomented war" quote directly to Armstrong, others suggest a similar sentiment was expressed by another director at a shareholders' meeting. Regardless, his consistent stance emphasized that the responsibility for the ethical application of his inventions lay with the users, not the engineers who created them.

8.2. Advocacy for Renewable Energy

Armstrong was an early advocate for the use of renewable energy. In 1863, he predicted that Britain would cease to produce coal within two centuries, stating that coal "was used wastefully and extravagantly in all its applications." In addition to promoting hydroelectricity, he also supported solar power, highlighting its immense potential. He noted that the amount of solar energy received by an area of 1.0 acre (1 acre) in the tropics would "exert the amazing power of 4,000 horses acting for nearly nine hours every day," underscoring his forward-thinking vision for sustainable energy sources.

9. Evaluation and Legacy

William Armstrong's life culminated in significant recognition and an enduring legacy that shaped industrial practices, technological advancements, and philanthropic endeavors.

9.1. Honours and Recognition

Throughout his distinguished career, William Armstrong received numerous honours and recognitions:

- In 1846, he was made a Fellow of the Royal Society (FRS).

- In 1850, he received the Telford Medal from the Institution of Civil Engineers.

- In 1859, William Armstrong was knighted as a Knight Bachelor (Kt).

- He was made a Companion of the Order of the Bath in the Civil Division.

- In 1874, he was elected an International Member of the American Philosophical Society.

- In 1878, he received the Albert Medal from the Royal Society of Arts.

- In 1886, he was awarded the Freedom of the City of Newcastle upon Tyne.

- In 1887, he was raised to the peerage as a Hereditary peer, allowing him to sit in the House of Lords. He took the title Baron Armstrong, of Cragside in the County of Northumberland.

- In 1891, he received the Bessemer Gold Medal from the Iron and Steel Institute.

He also received several honorary degrees:

| Location | Date | School | Degree |

|---|---|---|---|

| England | 1862 | University of Cambridge | Doctor of Laws (LL.D) |

| England | 1870 | University of Oxford | Doctor of Civil Law (DCL) |

| England | 1882 | University of Durham | Doctor of Civil Law (DCL) |

9.2. Industrial and Societal Impact

William Armstrong's impact on engineering, manufacturing, and naval technology was profound and lasting. His development of the hydraulic crane and the hydraulic accumulator revolutionized industrial power transmission. The Armstrong Gun fundamentally changed artillery design, leading to the adoption of breech-loading, rifled cannons globally and establishing his company as a dominant force in armaments. The Elswick works, under his leadership, grew into a sprawling industrial complex, significantly boosting the population and economic development of Tyneside. His company's ability to build and fully arm battleships made it a unique and influential player in global naval power.

His fame as a gun-maker was such that he is thought to be a possible model for George Bernard Shaw's arms magnate in Major Barbara, and the title character in Iain Pears' historical-mystery novel Stone's Fall also bears similarities to Armstrong.

Beyond his industrial achievements, Armstrong's philanthropic contributions left an indelible mark on his community, providing public parks, supporting educational institutions, and funding hospitals and museums. His visionary advocacy for renewable energy, particularly hydroelectric and solar power, demonstrated a foresight that predated widespread environmental concerns. Although he had no children, his legacy continued through his great-nephew and the enduring institutions and innovations he fostered. Upon his death, Andrew Noble, his former protégé, succeeded him as chairman of the company.