1. Early Life and Education

Wilfrid Laurier's early life was marked by a bicultural upbringing and a growing interest in liberal politics, which significantly shaped his future career as a conciliator in Canadian public life.

1.1. Childhood and Family Background

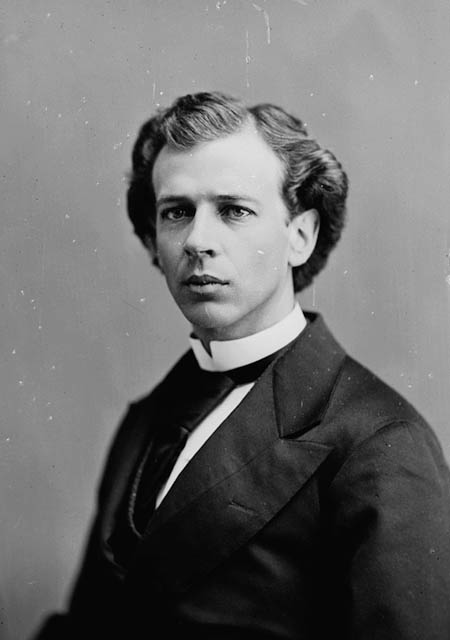

Henri Charles Wilfrid Laurier was born on November 20, 1841, in Saint-Lin, Canada East (now Saint-Lin-Laurentides, Quebec). He was the second child of Carolus Laurier and Marcelle Martineau and a sixth-generation French Canadian, tracing his ancestry to François Cottineau, dit Champlaurier, from Saint-Claud, France. Laurier grew up in a household where political discourse and debate were common. His father, an educated man with liberal views, held respected positions in the community, including farmer, surveyor, mayor, justice of the peace, militia lieutenant, and school board member.

At the age of 11, Laurier left home to study in New Glasgow, a nearby village predominantly settled by Scottish immigrants. For the next two years, he immersed himself in the culture, language, and mindset of English Canada, becoming fluent in English. In 1854, Laurier enrolled at the Collège de L'Assomption, a staunchly Catholic institution. Despite the school's conservative environment, it was here that he began to develop an interest in politics and embrace the principles of liberalism.

1.2. Education and Early Influences

In September 1861, Laurier commenced his legal studies at McGill University in Montreal. During his time at McGill, he met Zoé Lafontaine, who would later become his wife. He also discovered he suffered from chronic bronchitis, an illness that affected him throughout his life. At McGill, Laurier joined the Parti rougeFrench, or Red Party, a centre-left political party active in Canada East. He graduated from McGill in 1864 and remained engaged with the Parti rougeFrench, serving as vice president of the Institut canadien de MontréalFrench, a literary society associated with the Rouge, from May 1864 to fall 1866. In August 1864, he joined the Liberals of Lower Canada, an anti-Confederation group composed of both moderate and radical factions. This group argued that Confederation would grant excessive power to the central government and could lead to discrimination against French Canadians.

2. Early Political Career

Wilfrid Laurier's early political career saw him transition from a struggling lawyer to an influential voice in both provincial and federal politics, laying the groundwork for his eventual leadership of the Liberal Party.

2.1. Legal Profession and Entry into Politics

After graduating from McGill, Laurier initially faced difficulties in his legal practice in Montreal. He opened his first law firm on October 27, 1864, but it closed within a month. His second office lasted only three months due to a lack of clients. In March 1865, facing near bankruptcy, Laurier established his third law firm, partnering with Médéric Lanctot, a lawyer and journalist known for his strong opposition to Confederation. Their partnership achieved some success, but in late 1866, Laurier accepted an invitation from fellow Rouge member Antoine-Aimé Dorion to take over as editor and manager of the newspaper Le DéfricheurFrench.

Laurier relocated to Victoriaville and began editing Le Défricheur on January 1, 1867. He saw this as an opportunity to articulate his strong anti-Confederation views, writing, "Confederation is the second stage on the road to 'anglification' mapped out by Lord Durham...We are being handed over to the English majority...[We must] use whatever influence we have left to demand and obtain a free and separate government." However, Le Défricheur was forced to cease publication on March 21, 1867, due to financial difficulties and opposition from the local clergy. Confederation was officially proclaimed on July 1, 1867, marking a defeat for Laurier's initial stance.

Despite this setback, Laurier chose to remain in Victoriaville, where he gradually gained recognition. He was elected mayor and established a law practice that would last three decades, partnering with four different individuals. While not accumulating great wealth, he earned a respectable income. During this period, Laurier shifted his political stance, accepting Confederation and identifying himself as a moderate liberal, moving away from his earlier radical views.

In 1869, while residing in Victoriaville, Laurier was appointed an ensign in the Arthabaskaville Infantry Company. He was promoted to lieutenant in 1870 and was on active service in Saint-Hyacinthe from May to June during the second Fenian Raid. He continued his service until 1878 and was later awarded the Canada General Service Medal in 1899 for his actions in 1870.

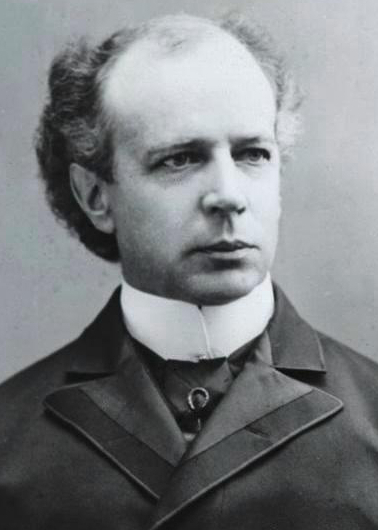

2.2. Member of Parliament

A member of the Quebec Liberal Party, Laurier was elected to the Legislative Assembly of Quebec for the riding of Drummond-Arthabaska in the 1871 Quebec general election. Although the Liberal Party suffered a significant defeat overall, Laurier campaigned successfully on pledges to increase funding for education, agriculture, and colonization. His tenure as a provincial politician was not particularly prominent, with few speeches delivered in the legislature.

Laurier resigned from the provincial legislature to enter federal politics as a Liberal. He was elected to the House of Commons in the January 22, 1874 election, representing the riding of Drummond-Arthabaska. This election saw a decisive victory for the Liberals, led by Alexander Mackenzie, largely due to the Pacific Scandal that implicated the Conservative Party and then-Prime Minister John A. Macdonald. Laurier's campaign was straightforward, focusing on denouncing Conservative corruption.

As a member of Parliament (MP), Laurier's initial goal was to establish his presence through speeches in the House of Commons. He gained considerable attention for a speech on political liberalism delivered on June 26, 1877, before an audience of approximately 2,000 people. In this address, he asserted, "Liberal Catholicism is not political liberalism" and clarified that the Liberal Party was not "a party composed of men holding perverse doctrines, with a dangerous tendency, and knowingly and deliberately progressing towards revolution." He also defined the party's policy as protecting, defending, and expanding Canada's institutions, and developing the country's resources. This speech was pivotal in solidifying Laurier's position as a leader within the Quebec wing of the Liberal Party.

2.3. Minister of Inland Revenue

From October 1877 to October 1878, Laurier served briefly in the Cabinet of Prime Minister Mackenzie as minister of inland revenue. His appointment necessitated a ministerial by-election on October 27, 1877, in which he lost his seat in Drummond-Arthabaska. However, he subsequently ran for and narrowly won the seat of Quebec East on November 11. Quebec East remained Laurier's constituency from November 11, 1877, until his death on February 17, 1919. Laurier won re-election for Quebec East in the 1878 federal election, despite the Liberals' significant defeat due to their handling of the Panic of 1873, which led to Macdonald's return as prime minister.

3. Leader of the Liberal Party and Opposition

Wilfrid Laurier's leadership of the Liberal Party and his time as Leader of the Opposition were crucial periods during which he rebuilt the party's strength and prepared it for government.

Laurier advocated for Mackenzie's resignation as leader, particularly criticizing his economic policies. Mackenzie resigned in 1880 and was succeeded by Edward Blake. Laurier, along with others, co-founded L'Électeur, a Quebec newspaper dedicated to promoting the Liberal Party. While in opposition, Laurier supported laissez-faire economics and provincial rights. The Liberals faced another defeat in the 1882 election, resulting in Macdonald's fourth term as prime minister. Laurier continued to deliver speeches opposing the Conservative government's policies, though his most notable intervention during this period came in 1885 when he spoke out against the execution of Métis leader Louis Riel. The Macdonald government had refused clemency for Riel after he led the North-West Rebellion, and Laurier's impassioned defense of Riel highlighted the need for unity between French and English Canadians.

3.1. Becoming Party Leader

Edward Blake resigned as Liberal leader after consecutive defeats in the 1882 and 1887 elections. Blake urged Laurier to seek the party leadership. Initially, Laurier was hesitant to assume such a demanding role, but he eventually accepted. By this time, after 13 and a half years in federal politics, Laurier had established a strong reputation as a prominent politician. He was recognized for leading the Quebec branch of the Liberal Party, for defending French Canadian rights, and as a formidable orator and parliamentary speaker. Over the next nine years, Laurier skillfully consolidated his party's influence, cultivating a strong personal following across Canada, particularly in Quebec.

3.2. Role as Leader of the Opposition

In the 1891 federal election, Laurier challenged Conservative Prime Minister John A. Macdonald. Laurier advocated for reciprocity, or free trade, with the United States, a position contrary to Macdonald's, who warned that such a policy could lead to American annexation of Canada. On election day, March 5, the Liberals gained 10 seats and, for the first time since 1874, secured a majority of seats in Quebec. However, Prime Minister Macdonald achieved his fourth consecutive federal election victory. The day after the election, Edward Blake publicly criticized the Liberal trade policy.

Laurier remained disheartened for some time following his defeat, repeatedly suggesting his resignation as leader, but he was persuaded by other Liberals to remain. It was not until 1893 that Laurier regained his resolve. On June 20 and 21, 1893, he convened a Liberal convention in Ottawa. The convention affirmed that unrestricted reciprocity was intended to develop Canada's natural resources and that customs tariffs would remain in place primarily to generate revenue. Following the convention, Laurier embarked on a series of speaking tours to promote these policies. During his visit to Western Canada in September and October 1894, he promised to relax the Conservatives' National Policy, open the American market, and increase immigration.

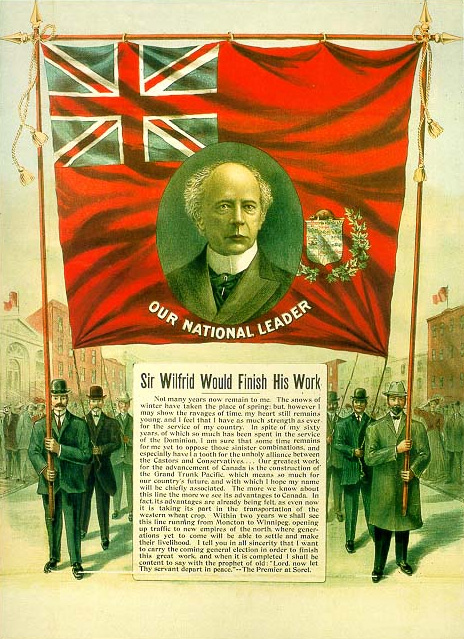

Macdonald passed away just three months after his 1891 election victory over Laurier. His death plunged the Conservative Party into a period of disorganization, with four leaders holding the prime ministership for short terms. The fourth prime minister after Macdonald, Charles Tupper, assumed office in May 1896 following the resignation of Mackenzie Bowell. Bowell's resignation was triggered by a leadership crisis stemming from his attempts to resolve the Manitoba Schools Question, a dispute that arose after the provincial government ended public funding for Catholic schools in 1890. Tupper faced Laurier in the 1896 federal election, where the schools dispute became a central issue. While Tupper supported federal legislation to override the provincial law and reinstate funding for Catholic schools, Laurier maintained a deliberately vague stance. He proposed an initial investigation followed by conciliation, a method he famously termed "sunny ways" (voies ensoleilléesFrench). On June 23, Laurier led the Liberals to their first federal victory in 22 years, largely due to his strong performance in Quebec, despite losing the popular vote nationally.

4. Prime Minister of Canada (1896-1911)

Laurier's fifteen-year tenure as Prime Minister of Canada was a period of significant growth and change, marked by ambitious domestic policies and an evolving approach to Canada's place in the world.

4.1. Domestic Policy

Laurier's domestic policies focused on resolving national disputes, expanding infrastructure, fostering economic growth through immigration, and addressing social and labour issues.

4.1.1. Manitoba Schools Question

One of Laurier's immediate priorities as prime minister was to find a resolution to the Manitoba Schools Question, a contentious issue that had contributed to the downfall of Charles Tupper's Conservative government earlier in 1896. The Manitoba legislature had enacted a law abolishing public funding for Catholic schools. Supporters of Catholic schools argued that this new statute violated provisions of the Manitoba Act, 1870, which contained clauses related to school funding. However, the courts rejected this argument, ruling the new statute constitutional. The Catholic minority in Manitoba then sought assistance from the federal government, leading the previous Conservative administration to propose remedial legislation to override Manitoba's law. Laurier, however, had opposed this remedial legislation, advocating for provincial rights and successfully blocking its passage in Parliament.

Once elected, Laurier negotiated a compromise with Manitoba's provincial premier, Thomas Greenway, known as the Laurier-Greenway Compromise. This agreement did not reinstate separate Catholic schools. Instead, it stipulated that religious instruction (Catholic education) could occur for 30 minutes at the end of each school day, provided it was requested by parents of 10 children in rural areas or 25 children in urban areas. Catholic teachers could be hired in schools if there were at least 40 Catholic students in urban areas or 25 Catholic students in rural areas. Furthermore, teachers were permitted to instruct in French or any other minority language if there were a sufficient number of Francophone students. While many viewed this as the best possible solution under the circumstances, some French Canadians criticized the compromise, arguing it addressed the issue on an individual basis rather than comprehensively protecting Catholic or French language rights in all schools. Laurier referred to his approach to de-escalate this volatile issue as "sunny ways."

4.1.2. Railway Construction

Laurier's government significantly expanded Canada's railway network. It introduced and initiated the construction of a second transcontinental railway, the Grand Trunk Pacific Railway, recognizing the limitations of the existing Canadian Pacific Railway in meeting the growing needs of the country. In the West, the CPR struggled to transport all agricultural products, while in the East, its lines did not extend into Northern Ontario and Northern Quebec. Laurier favoured a transcontinental line built entirely on Canadian land through private enterprise.

His government also oversaw the construction of a third railway, the National Transcontinental Railway. This line was intended to provide Western Canada with a direct rail connection to the Atlantic ports and to facilitate the development of Northern Ontario and Northern Quebec. Laurier believed that increased competition among the three railways would compel the Canadian Pacific Railway to lower freight rates, benefiting Western shippers and contributing to overall market competition. Initially, Laurier approached the Grand Trunk Railway and Canadian Northern Railway to build the National Transcontinental railway. However, due to disagreements between the two companies, Laurier's government decided to construct part of the railway itself. Eventually, a deal was struck with the Grand Trunk Pacific Railway Company (a subsidiary of the Grand Trunk Railway Company) to build the western section, extending from Winnipeg to the Pacific Ocean, while the government undertook construction of the eastern section, from Winnipeg to Moncton. Upon completion, Laurier's government would transfer the railway to the company for operation. However, the substantial cost of constructing this railway drew significant public criticism.

During his government's dealings with railway contractors, Laurier developed a close friendship with Canadian railway magnate Hugh Ryan, which lasted until Ryan's death in 1899. Laurier was notably the first to publicly and privately offer condolences to Ryan's family.

4.1.3. Provincial and Territorial Expansion

On September 1, 1905, Laurier oversaw the entry of Alberta and Saskatchewan into Confederation through the enactment of the Alberta Act and the Saskatchewan Act. These were the last two provinces to be carved out of the Northwest Territories. Laurier chose to create two distinct provinces, arguing that a single, large province would be too difficult to govern effectively. This expansion followed the Laurier Government's enactment of the Yukon Territory Act in 1898, which separated the Yukon from the Northwest Territories. Also in 1898, Quebec's boundaries were expanded under the Quebec Boundary Extension Act.

4.1.4. Immigration Policy and Social Impact

Laurier's government significantly increased immigration to stimulate economic growth. Between 1897 and 1914, over one million immigrants arrived in Canada, contributing to a 40 percent increase in the national population. Laurier's immigration policy specifically targeted the Prairies, believing that increased settlement there would boost farming production and benefit the agriculture industry.

However, the influx of immigrants, particularly from Asia, sparked alarm in British Columbia, where a "whites-only" policy was adopted by the electorate. While railway and large companies sought to hire Asian laborers, labor unions and the general public largely opposed their presence. Both major political parties, including Laurier's Liberals, aligned with public opinion. Critics have pointed to Laurier's actions as reflecting racist views, citing his support for discriminatory measures such as the Chinese head tax. In 1900, Laurier's government raised the Chinese head tax to 100 CAD, and further increased it to 500 CAD in 1903. He even proposed raising the sum to 1.00 K CAD when some Chinese immigrants still managed to pay the 500 CAD fee. This was not an isolated incident; Laurier's political career included other racially motivated actions and expressions of views. In 1886, he stated in the House of Commons that it was morally justifiable for Canada to appropriate lands from "savage nations" provided adequate compensation was paid. Laurier also negotiated limits on Japanese emigration to Canada.

In August 1911, Laurier approved the Order-in-Council P.C. 1911-1324, recommended by the minister of the interior, Frank Oliver. This order, approved by cabinet on August 12, 1911, was designed to prevent Black Americans fleeing segregation in the American South from entering Canada, explicitly stating that "the Negro race...is deemed unsuitable to the climate and requirements of Canada." The order was never formally enacted, as existing efforts by immigration officials had already reduced the number of Black migrants to Canada. It was officially canceled on October 5, 1911, the day before Laurier left office, with the cabinet citing the minister of the interior's absence at the time of its initial approval.

4.1.5. Social and Labour Legislation

In March 1906, Laurier's government introduced the Lord's Day Act, influenced by the Lord's Day Alliance. The act, which took effect on March 1, 1907, prohibited business transactions on Sundays and restricted Sunday trade, labor, recreation, and newspapers. The legislation garnered support from organized labor and the French Canadian Catholic hierarchy. However, it faced opposition from those in the manufacturing and transportation sectors, as well as from French Canadians who viewed it as federal interference in a provincial matter. The Quebec government subsequently passed its own Lord's Day Act, which became effective one day before the federal act.

In 1907, Laurier's government passed the Industrial Disputes Investigation Act. This legislation mandated conciliation between employers and workers before any strike in public utilities or mines. However, it did not require the parties to accept the conciliators' report. In 1908, a system was introduced enabling individuals to purchase annuities from the government, aimed at encouraging voluntary provision for old age.

4.2. Foreign Policy and Imperial Relations

Laurier's foreign policy focused on asserting Canada's growing autonomy within the British Empire while maintaining close ties with the United Kingdom and addressing international disputes.

4.2.1. Relations with the United Kingdom and the Empire

On June 22, 1897, Laurier attended the Diamond Jubilee of Queen Victoria, marking the 60th anniversary of her accession. During this visit, he was knighted and received various honors, honorary degrees, and medals. He revisited the United Kingdom in 1902, participating in the 1902 Colonial Conference and the coronation of King Edward VII on August 9, 1902. Laurier also took part in the 1907 and 1911 Imperial Conferences.

4.2.2. Canadian Autonomy and International Standing

Laurier actively sought to establish Canada as an autonomous country within the British Empire, balancing loyalty to the Crown with the assertion of Canadian interests. He believed that Canada should remain within the British Empire, but only if it was founded upon "absolute freedom of political and commercial relations." On June 1, 1909, his government established the Department of External Affairs, signifying Canada's desire for greater control over its foreign policy. He famously declared, "My eyes are always, as a pillar of fire by night and a pillar of cloud by day, standing for a true Canadianism, moderation, conciliation." He also passionately defended individual liberty, stating, "Canada is free and freedom is its nationality," and "Nothing will prevent me from pursuing my duty of preserving at all costs our civil liberties."

4.2.3. Second Boer War

In 1899, the British government requested Canadian troops to serve in the Second Boer War. This request created a significant division within Canada: English Canadians largely supported sending military assistance, while French Canadians strongly opposed involvement. Laurier found himself caught between these opposing demands. He ultimately decided to send a volunteer force, rather than deploying the regular Canadian Militia, as Britain had anticipated. Approximately 7,000 Canadian soldiers served in the conflict. French Canadian nationalist and Liberal MP Henri Bourassa was a particularly vocal opponent of any Canadian participation in the Boer War, resigning from the Liberal caucus in October 1899 in protest. Laurier's compromise aimed to soothe tensions but highlighted the deep linguistic and cultural divide within the nation. Canada also contributed 620.00 K GBP to the war effort.

4.2.5. Alaska Boundary Dispute

In 1897 and 1898, the Alaska-Canada border became a critical issue, exacerbated by the Klondike Gold Rush. Laurier demanded an all-Canadian route from the gold fields to a seaport and sought to establish an exact boundary, including ownership of the Lynn Canal and control over maritime access to the Yukon. Laurier and U.S. President William McKinley agreed to establish a joint Anglo-American commission to study and resolve the dispute. However, this commission proved unsuccessful and abruptly concluded on February 20, 1899.

The dispute was then referred to an international judicial commission in 1903. This commission comprised three American politicians (Elihu Root, Henry Cabot Lodge, and George Turner), two Canadians (Allen Bristol Aylesworth and Louis-Amable Jetté), and one Briton (Lord Alverstone, Lord Chief Justice of England). On October 20, 1903, the commission, by a majority vote (Root, Lodge, Turner, and Alverstone), ruled in favor of the American government's claims. Canada acquired only two islands below the Portland Canal. This decision sparked a wave of anti-American and anti-British sentiment in Canada, which Laurier temporarily encouraged. The dispute had contributed to the Canadian government's decision in 1898 to create the Yukon Territory to prevent American annexation.

4.2.6. Tariffs and Trade Agreements

Although generally supportive of free trade with the United States, Laurier did not actively pursue the idea early in his premiership because the American government refused to engage in discussions on the matter. Instead, he implemented a Liberal adaptation of the Conservatives' nationalist and protectionist National Policy. This involved maintaining high tariffs on goods from countries that restricted Canadian imports, while simultaneously lowering tariffs to a reciprocal level for countries that admitted Canadian goods.

In 1897, Laurier's government introduced a preferential tariff reduction of 12.5 percent for countries that imported Canadian goods at a rate equivalent to Canada's minimum charge. Tariff rates remained unchanged for countries that imposed protective duties against Canada. This policy largely satisfied both proponents of free trade (due to the preferential reduction) and those who supported protectionism (as elements of the National Policy remained).

Laurier's government further reformed tariffs in 1907, introducing a "three-column tariff." This system added a new intermediate rate (a bargaining rate) alongside the existing British preferential rate and the general rate (which applied to all countries without most-favoured-nation agreements with Canada). While the preferential and general rates stayed the same, the intermediate rates were slightly lower than the general rates.

Also in 1907, Laurier's minister of finance, William Stevens Fielding, and minister of marine and fisheries, Louis-Philippe Brodeur, negotiated a trade agreement with France that reduced import duties on certain goods. In 1909, Fielding also successfully negotiated an agreement to promote trade with the British West Indies.

4.3. Election Victories

Under Laurier's leadership, the Liberal Party secured three consecutive re-elections in the 1900, 1904, and 1908 federal elections. The Liberal Party's popular vote and seat share increased in both the 1900 and 1904 elections. Although the party's popular vote and seat share slightly decreased in the 1908 election, they still maintained a strong majority.

By the late 1800s, Laurier had successfully transformed Quebec into a stronghold for the Liberal Party. For decades, Quebec had been a Conservative bastion, due to the province's social conservatism and the powerful influence of the Roman Catholic Church, which generally distrusted the Liberals' anti-clericalism. However, the growing alienation of French Canadians from the Conservative Party, particularly due to its connections with anti-French and anti-Catholic Orangemen in English Canada, greatly benefited the Liberal Party. Following the decline of the Conservative Party of Quebec, Laurier established a dominant base in French Canada and among Catholics nationwide. Despite this, Catholic priests in Quebec repeatedly cautioned their parishioners against voting Liberal, famously using the slogan "le ciel est bleu, l'enfer est rougeFrench" ("heaven is blue, hell is red"), referencing the traditional colors of the Conservative and Liberal parties.

4.4. Supreme Court Appointments

During his premiership, Wilfrid Laurier advised the Governor General to appoint the following individuals to the Supreme Court of Canada:

- Sir Louis Henry Davies (September 25, 1901 - May 1, 1924)

- David Mills (February 8, 1902 - May 8, 1903)

- Sir Henri Elzéar Taschereau (as Chief Justice November 21, 1902 - May 2, 1906; appointed a Puisne Justice under Prime Minister Mackenzie, October 7, 1878)

- John Douglas Armour (November 21, 1902 - July 11, 1903)

- Wallace Nesbitt (May 16, 1903 - October 4, 1905)

- Albert Clements Killam (August 8, 1903 - February 6, 1905)

- John Idington (February 10, 1905 - March 31, 1927)

- James Maclennan (October 5, 1905 - February 13, 1909)

- Sir Charles Fitzpatrick (as Chief Justice, June 4, 1906 - November 21, 1918)

- Sir Lyman Poore Duff (September 27, 1906 - January 2, 1944)

- Francis Alexander Anglin (February 23, 1909 - February 28, 1933)

- Louis-Philippe Brodeur (August 11, 1911 - October 10, 1923)

5. Reciprocity Election of 1911 and Defeat

The 1911 federal election proved to be a pivotal moment in Canadian politics, leading to Laurier's defeat and the end of 15 years of Liberal rule.

5.1. The Reciprocity Agreement

In 1911, a significant controversy emerged surrounding Laurier's support for a trade reciprocity agreement with the United States. His long-serving minister of finance, William Stevens Fielding, had negotiated a deal that would allow for the free trade of natural products and a general lowering of tariffs. This agreement found strong support among agricultural interests, particularly in Western Canada. However, it alienated many businessmen, who constituted a substantial part of the Liberal base, and raised concerns about increased competition for industries.

The Conservatives vehemently denounced the agreement, playing on long-standing fears that reciprocity could ultimately weaken Canada's ties with Britain and lead to the dominance of the Canadian economy by the United States. They also campaigned on anxieties that the treaty would erode Canadian identity and potentially result in the American annexation of Canada. The debate surrounding this proposed trade deal became the central issue of the election.

5.2. Election Campaign and Outcome

Facing an increasingly unruly House of Commons, including vocal disapproval from prominent Liberal MP Clifford Sifton, Laurier called an election to resolve the issue of reciprocity. The ensuing campaign was fiercely contested. On September 21, 1911, the Conservatives emerged victorious, and the Liberals lost over a third of their seats. The Conservative leader, Robert Laird Borden, succeeded Laurier as prime minister, bringing an end to 15 consecutive years of Liberal governance.

6. Opposition and World War I (1911-1919)

Following his defeat in 1911, Wilfrid Laurier remained as Leader of the Opposition, guiding the Liberal Party through a tumultuous period that included World War I and the divisive Conscription Crisis.

6.1. Leadership in Opposition

Despite his electoral defeat, Laurier continued to serve as the leader of the Liberal Party. In December 1912, he took the lead in a filibuster against the Conservative government's naval bill, which proposed allocating 35.00 M CAD to assist the Royal Navy. Laurier argued that this bill threatened Canada's autonomy. After six months of intense debate, the bill was successfully blocked by the Liberal-controlled Senate.

6.2. World War I and the Conscription Crisis

Laurier led the opposition during World War I. He supported Canada's participation in the war by sending a volunteer force, believing that an intensive recruitment campaign would yield sufficient troops. Prime Minister Borden initially relied on a volunteer military system, but as applications declined, he imposed conscription in the summer of 1917, which led to the Conscription Crisis of 1917. Laurier became an influential opponent of conscription, a position widely applauded by French Canadians, who generally opposed compulsory military service.

The conscription debate caused deep divisions within the Liberal Party. Pro-conscription Liberals, particularly from English Canada, joined Borden as Liberal-Unionists to form the Union government. Laurier, however, refused to join the Unionist Party, instead forming the "Laurier Liberals", a faction composed of Liberals opposed to conscription. He also rejected Borden's proposal to form a coalition government of Conservatives and Liberals, arguing that it would eliminate any "real" opposition to the government. Laurier further contended that if the Liberals joined such a coalition, Quebec would feel alienated, potentially falling under the heavy influence of the outspoken French-Canadian nationalist Henri Bourassa and what Laurier termed Bourassa's "dangerous nationalism," which he feared could lead to Quebec seceding from Canada.

6.3. The 1917 Election

The 1917 federal election was largely fought on the issue of conscription. The Laurier Liberals were reduced to a largely French Canadian rump. Despite the national defeat, Laurier swept Quebec, winning 62 out of 65 of the province's seats. This strong showing was primarily due to the overwhelming respect and support he garnered from French Canadians for his steadfast opposition to conscription.

The Conscription Crisis profoundly exposed and exacerbated the long-standing divisions between French Canadians and English Canadians. Most English Canadians favored conscription, believing it would strengthen ties with Britain, while most French Canadians opposed it, seeking to distance themselves from the European conflict. Laurier was subsequently viewed as a "traitor" by English Canadians and many English Canadian Liberals, while he was hailed as a "hero" by French Canadians. Laurier's protégé and eventual successor as party leader, William Lyon Mackenzie King, later succeeded in unifying the English and French factions of the Liberal Party, leading it to victory over the Conservatives in the 1921 federal election.

After the 1917 election, Laurier continued to serve as both Liberal leader and Leader of the Opposition. When World War I concluded on November 11, 1918, he focused his efforts on rebuilding and reunifying the Liberal Party.

7. Personal Life

Beyond his public career, Wilfrid Laurier's personal life included a long marriage and complex relationships that shaped his private world.

7.1. Marriage and Family

Wilfrid Laurier married Zoé Lafontaine in Montreal on May 13, 1868. Zoé, born in Montreal, was the daughter of G.N.R. Lafontaine and his first wife, Zoé Tessier (also known as Zoé Lavigne). She was educated at the School of the Bon Pasteur and the Convent of the Sisters of the Sacred Heart, St. Vincent de Paul. The couple resided in Arthabaskaville until they relocated to Ottawa in 1896. Zoé was an active figure in public life, serving as one of the vice presidents upon the formation of the National Council of Women and as an honorary vice president of the Victorian Order of Nurses. The couple had no children.

7.2. Personal Relationships

Beginning in 1878 and continuing for approximately two decades while married to Zoé, Laurier maintained an "ambiguous relationship" with Émilie Barthe, a married woman. Unlike Zoé, who was not an intellectual, Émilie shared Laurier's passion for literature and politics, reportedly winning his affection. Despite rumors that he fathered a son, Armand Lavergne, with her, Zoé remained with Laurier until his death.

8. Death and Succession

Wilfrid Laurier died while still actively serving as Leader of the Opposition, and his passing prompted a transition within the Liberal Party.

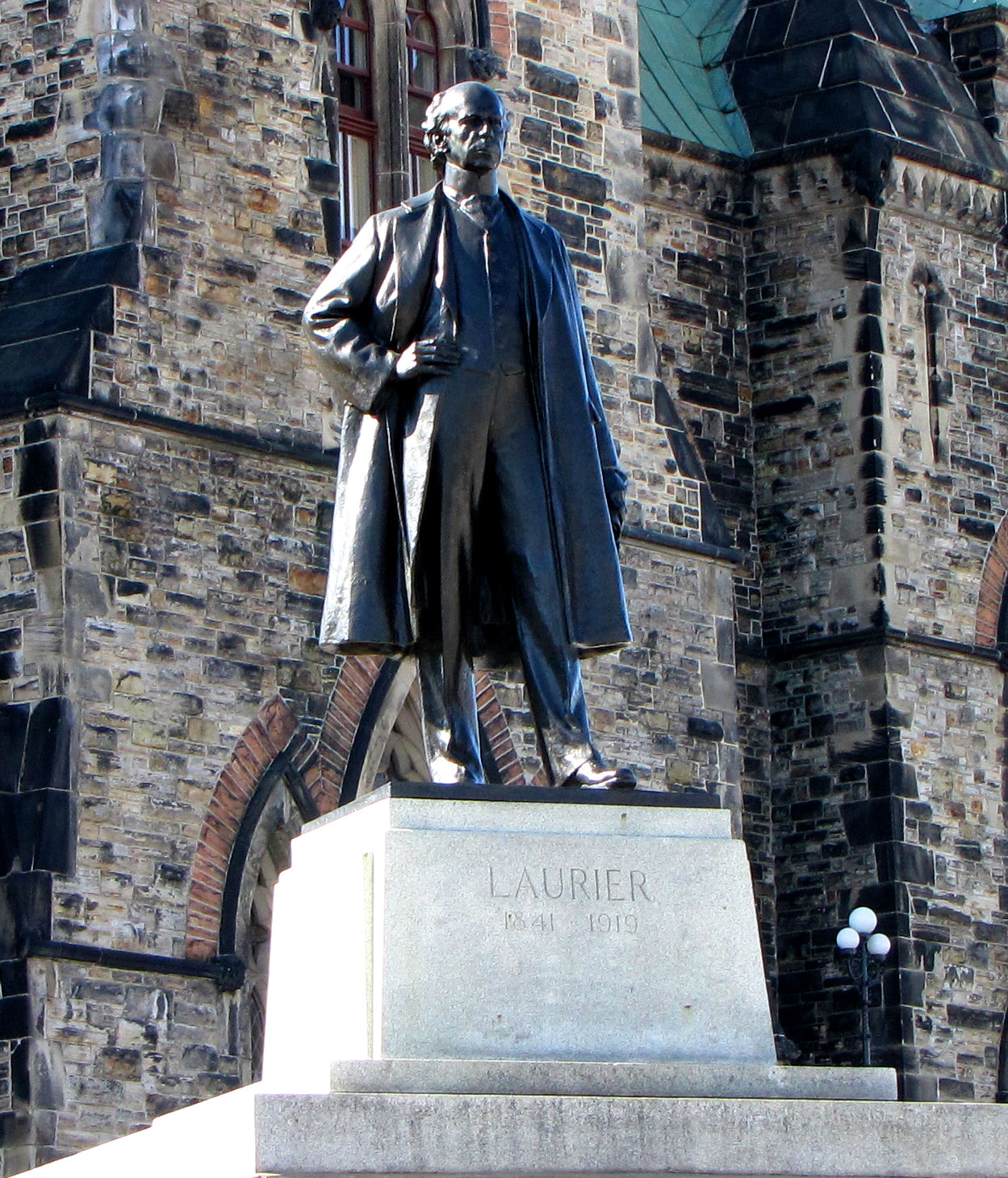

Laurier died of a stroke on February 17, 1919, while still in office as leader of the Opposition. Despite having lost a difficult election two years prior, he was widely admired across the nation for his "warm smile, his sense of style, and his his 'sunny ways'." His state funeral drew an immense crowd, with an estimated 50,000 to 100,000 people filling the streets of Ottawa as his funeral procession made its way to his final resting place at Notre-Dame Cemetery. His remains were interred in a stone sarcophagus, adorned with sculptures of nine mourning female figures, each symbolizing one of the provinces in the Canadian union. His wife, Zoé Laurier, passed away on November 1, 1921, and was laid to rest in the same tomb.

Laurier was permanently succeeded as Liberal leader by his former minister of labour, William Lyon Mackenzie King, who narrowly defeated Laurier's former minister of finance, William Stevens Fielding, in the leadership election. According to Zoé Laurier, Fielding was Wilfrid's preferred choice for the next leader, as he believed Fielding had the best chance of restoring unity within the party.

9. Legacy and Assessment

Wilfrid Laurier's political career left an indelible mark on Canada, shaping its national identity, economic trajectory, and internal dynamics, though his legacy is also subject to critical examination.

9.1. Historical Reputation and Rankings

Overall, Laurier's steadfast efforts to maintain neutrality between English and French Canadians, and his persistent pursuit of a middle ground between the two linguistic groups, have contributed to his high standing among Canadian prime ministers. He is consistently ranked among the top three. Despite being a French Canadian, he did not fully concede to French Canadian demands for the repeal of Manitoba's ban on public funding for Catholic schools, nor did he completely accede to their requests to refuse any Canadian military involvement in the Boer War. Nevertheless, in all seven federal elections he contested, the majority of Quebec's ridings voted for his Liberal Party. With one notable exception in the 1958 election, the Liberal Party continued to dominate federal politics in Quebec until the 1984 election.

Historian Jacques Monet observed that to his loyal supporters, especially in Quebec where his surname is often used as a first name by other Canadians, Laurier remains a charismatic hero whose time in office was a prosperous period in Canadian history. Monet praised Laurier for working throughout his life for cooperation between French- and English-speaking Canadians while striving to keep Canada as independent as possible from Britain. His personal charm, dignity, oratorical skill, and intellectual gifts earned him the admiration of both Canadians and non-Canadians alike.

According to historians Norman Hillmer and Stephen Azzi, a 2011 poll of 117 historians and experts voted Laurier as the "best" Canadian prime minister, surpassing John A. Macdonald and Mackenzie King. Laurier was also ranked Number 3 among the Prime Ministers of Canada (out of the 20 up to Jean Chrétien) in a survey by Canadian historians compiled in Prime Ministers: Ranking Canada's Leaders by J.L. Granatstein and Norman Hillmer. Tim Cook of the Canadian War Museum described Sir Wilfrid as "the full package," being "passionate, charismatic, and an intellectual force in both languages."

9.2. Contributions to Canadian Unity and Identity

Laurier's approach to governance centered on fostering national unity. His "sunny ways" philosophy exemplified his commitment to finding compromises that could bridge linguistic and cultural divides, preventing national fragmentation. He actively worked to promote bilingualism and to cultivate a distinct Canadian identity, one that balanced loyalty to the British Empire with an assertion of Canadian self-governance and unique interests. His consistent electoral success, particularly in uniting diverse regions and linguistic groups under the Liberal banner, demonstrated his ability to articulate a vision of Canada as a cohesive nation.

9.3. Economic Development and Modernization

Laurier's government played a crucial role in Canada's economic development and modernization at the turn of the 20th century. He famously declared that the "20th century belongs to Canada," setting an ambitious tone for national growth. His policies aggressively promoted immigration to populate the West and stimulate agricultural production, contributing to a significant increase in Canada's population and economic output. The expansion of the railway network, including the Grand Trunk Pacific and National Transcontinental railways, was central to his vision for economic integration and opening up new territories for settlement and resource extraction. While these initiatives spurred industrial development and trade, they also incurred substantial public cost and faced criticism. His trade policies, including the modified National Policy and preferential tariffs, aimed to protect Canadian industries while also expanding international trade relations, particularly with the British Empire and France.

9.4. Criticisms and Controversies

Despite his revered status as a nation-builder and conciliator, Laurier has faced increasing criticism in recent times, particularly concerning his policies towards Indigenous peoples and immigrants from China and India. While his government promoted immigration for economic growth, it simultaneously implemented measures to restrict the arrival of Chinese and Indian immigrants. This is evident in his support for the Chinese head tax and negotiations to limit Japanese emigration.

Furthermore, Laurier's encouragement of widespread settlement had significant adverse effects on local Indigenous populations, often leading to the displacement from their traditional lands. His statements, such as his 1886 assertion in the House of Commons that it was justifiable for Canada to take lands from "savage nations" with compensation, reflect racially charged views common in his era but now widely condemned. The approval of the Order-in-Council P.C. 1911-1324, aimed at excluding Black Americans, further underscores the discriminatory aspects of his immigration policies. These criticisms offer a more balanced and critical perspective on Laurier's complex legacy, acknowledging both his significant contributions to Canadian development and the profound negative impacts of his racially biased policies.

10. Recognition and Honours

Wilfrid Laurier has been extensively commemorated across Canada, with national historic sites, monuments, various honors, and numerous places named in his memory, reflecting his enduring significance in Canadian history.

10.1. National Historic Sites and Monuments

Laurier is commemorated by three National Historic Sites:

- The Sir Wilfrid Laurier National Historic Site is located in his birthplace, Saint-Lin-Laurentides, Quebec, approximately 37 mile (60 km) north of Montreal. The establishment of this site reflected an early desire, dating back to a plaque in 1925 and a monument in 1927, to create a shrine to Laurier in the 1930s. Despite initial doubts and later confirmation that the designated birthplace house was neither Laurier's actual home nor on its original site, its development, including the construction of a museum, fulfilled the objective of honoring the man and depicting his early life.

- Laurier's brick residence in Ottawa is known as Laurier House National Historic Site, situated at the corner of what is now Laurier Avenue and Chapel Street. In their wills, the Lauriers bequeathed the house to Prime Minister Mackenzie King, who in turn donated it to Canada upon his death. Both the Saint-Lin-Laurentides and Ottawa sites are administered by Parks Canada as part of the national park system.

- The 1876 Italianate residence of the Lauriers in Victoriaville, Quebec, where he lived during his years as a lawyer and Member of Parliament, is designated Wilfrid Laurier House National Historic Site. It is privately owned and operated as the Laurier Museum.

In November 2011, Wilfrid Laurier University in Waterloo, Ontario, unveiled a statue depicting a young Wilfrid Laurier seated on a bench, deep in thought.

10.2. Other Commemorations and Honours

Laurier received numerous titular honors throughout his life:

- He was granted the prenominal "The Honourable" and the postnominal "PC" for life upon being made a member of the Queen's Privy Council for Canada on October 8, 1877.

- His prenominal was elevated to "The Right Honourable" when he was made a member of the Imperial Privy Council of the United Kingdom in the 1897 Diamond Jubilee Honours.

- He received the prenominal "Sir" and postnominal "GCMG" as a knight grand cross of the Order of Saint Michael and Saint George, also bestowed in the 1897 Diamond Jubilee Honours.

- He was awarded an honorary LL.D. degree from the University of Edinburgh and the Freedom of the City of Edinburgh on July 26, 1902, during his visit to the city for the coronation of King Edward VII.

- Sir Wilfrid Laurier Day is observed annually on November 20, his birth date.

- Laurier's portrait has been featured on several banknotes issued by the Bank of Canada:

- The 1.00 K CAD note in the 1935 Series and 1937 Series.

- The 5 CAD note in the Scenes of Canada series (1972 and 1979), Birds of Canada series (1986), Journey series (2002), and Frontier series (2013).

- Laurier has appeared on at least three postage stamps, issued in 1927 (two) and 1973.

10.3. Places Named in Honour

Many sites and landmarks across Canada have been named to honor Wilfrid Laurier, including:

- Mount Sir Wilfrid Laurier, the highest peak in British Columbia's Premier Range, near Mount Robson.

- Sir Wilfrid Laurier Elementary, in Vancouver, British Columbia.

- Laurier Avenue, in Milton, Ontario.

- Avenue Laurier, in Shawinigan, Quebec.

- Mont-Laurier, Quebec.

- Laurier Boulevard, and Laurier Hill, in Brockville, Ontario.

- Avenue Laurier, in Montreal, Quebec.

- Boulevard Laurier, in Quebec City, Quebec.

- Laurier Avenue, in Ottawa, Ontario.

- Laurier Avenue, in Deep River, Ontario.

- Laurier Street, in North Bay, Ontario.

- Rue Laurier, in Casselman, Ontario.

- Rue Laurier Street, in Rockland, Ontario.

- The Laurier Heights neighbourhood, including Laurier Drive and Laurier Heights School, in Edmonton, Alberta.

- Laurier Drive, in Saskatoon's Confederation Park neighbourhood, where the majority of the streets are named after former Canadian prime ministers.

- The provincial electoral district of Laurier-Dorion (an honor shared with Canadian politician Antoine-Aimé Dorion).

- The federal electoral district of Laurier-Sainte-Marie.

- Wilfrid Laurier University (previously known as Waterloo Lutheran University), a publicly funded university in Waterloo, Ontario, with campuses in Brantford and Milton.

- A Montreal Metro station, Laurier (Montreal Metro).

- CCGS Sir Wilfrid Laurier.

- Château Laurier, a downtown Ottawa hotel of high reputation and a national historic site.

- Sir Wilfrid Laurier Public School in Markham, Ontario.

- Sir Wilfrid Laurier School Board, an English school board in Quebec; the school board serves the Laval, Laurentides, and Lanaudière regions in Quebec.

- Sir Wilfrid Laurier Secondary School in London, Ontario.

- Sir Wilfrid Laurier Secondary School in Ottawa, Ontario.

- Sir Wilfrid Laurier Collegiate Institute in Scarborough, Ontario.

11. In Popular Culture

Wilfrid Laurier's historical significance extends to popular culture, where he has been featured in modern media.

He appears as the leader of the Canadian civilization in the 4X video game Sid Meier's Civilization VI.

12. Electoral Record

Wilfrid Laurier's extensive political career included numerous electoral contests for both provincial and federal seats, showcasing his long-standing presence in Canadian politics.

| Election Name | Office Held | Term | Party | Vote Share | Votes | Rank | Result |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1874 Election | MP (Drummond-Arthabaska) | 3rd | Liberal | 53.57% | 1,786 | 1st | Won |

| 1877 By-election | MP (Quebec East) | 3rd | Liberal | 54.62% | 1,863 | 1st | Won |

| 1878 Election | MP (Quebec East) | 4th | Liberal | 62.49% | 1,946 | 1st | Won |

| 1882 Election | MP (Quebec East) | 5th | Liberal | 57.70% | 1,750 | 1st | Won |

| 1887 Election | MP (Quebec East) | 6th | Liberal | 79.05% | 2,622 | 1st | Won |

| 1891 Election | MP (Quebec East) | 7th | Liberal | Uncontested | Uncontested | 1st | Won |

| 1896 Election | MP (Quebec East) | 8th | Liberal | 76.00% | 3,202 | 1st | Won |

| 1896 Election | MP (Saskatchewan (Provisional District)) | 8th | Liberal | 46.06% | 988 | 1st | Won |

| 1896 By-election | MP (Quebec East) | 8th | Liberal | Uncontested | Uncontested | 1st | Won |

| 1900 Election | MP (Quebec East) | 9th | Liberal | 81.33% | 3,598 | 1st | Won |

| 1904 Election | MP (Quebec East) | 10th | Liberal | 71.35% | 3,524 | 1st | Won |

| 1904 Election | MP (Wright) | 10th | Liberal | 61.39% | 3,250 | 1st | Won |

| 1908 Election | MP (Quebec East) | 11th | Liberal | 70.83% | 3,764 | 1st | Won |

| 1908 Election | MP (Ottawa) | 11th | Liberal | 26.53% | 6,584 | 1st | Won |

| 1911 Election | MP (Quebec East) | 12th | Liberal | Uncontested | Uncontested | 1st | Won |

| 1911 Election | MP (Soulanges) | 12th | Liberal | 53.64% | 1,045 | 1st | Won |

| 1917 Election | MP (Quebec East) | 13th | Liberal | 92.53% | 6,957 | 1st | Won |