1. Early Life and Background

Vlad III's early life was marked by political instability and his family's complex relationship with the dominant powers of the region, which profoundly shaped his character and later rule.

1.1. Birth and Family

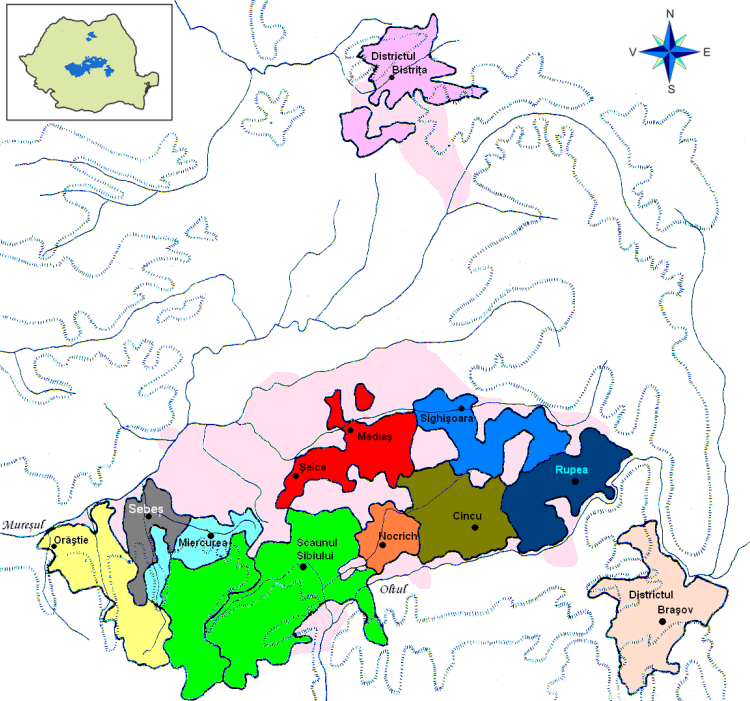

Vlad III was the second legitimate son of Vlad Dracul, who became the ruler of Wallachia in 1436. His birth is generally placed between 1428 and 1431, most likely after his father settled in Transylvania in 1429. Historian Radu Florescu suggests Vlad was born in the Transylvanian Saxon town of Sighișoara (then part of the Kingdom of Hungary), where his father resided in a three-story stone house from 1431 to 1435. His mother is identified by some modern historians as Cneajna of Moldavia, the eldest daughter of Alexander I, or as Vlad II's unknown first wife. Vlad is believed to have learned combat skills, geography, mathematics, science, languages such as Old Bulgarian, German, and Latin, and classical arts and philosophy during his upbringing.

Vlad's father, Vlad II, earned the sobriquet "Dracul" (DraculRomanian, "the Dragon") after being inducted into the Order of the Dragon, a militant fraternity founded by Sigismund of Luxemburg, King of Hungary. The Order was dedicated to resisting the Ottoman advance into Europe. Consequently, Vlad III's patronymic, "Dracula" (DrăculeaRomanian), means "son of the Dragon" or "belonging to the Dragon." In modern Romanian, the word dracul also translates to "the devil," a connotation that later contributed to Vlad's fearsome reputation. Vlad III had an elder brother, Mircea, and a younger brother, Radu. They were mentioned in documents from 1437 to 1439, with Radu appearing in the last of these.

1.2. Hostage in the Ottoman Empire

In 1442, Vlad II Dracul, caught between the Hungarian and Ottoman powers, met with John Hunyadi, the Voivode of Transylvania. After this meeting, Vlad II did not support an Ottoman invasion of Transylvania. In response, Murad II, the Ottoman Sultan, commanded Vlad II to appear in Gallipoli to demonstrate his loyalty. Vlad and his younger brother, Radu, accompanied their father to the Ottoman Empire, where they were all imprisoned. While Vlad II was released before the end of the year, Vlad and Radu remained as hostages to ensure their father's continued loyalty. They were held in the fortress of Eğrigöz, Emit, according to contemporary Ottoman chronicles.

Their lives were particularly endangered when their father supported Vladislaus, King of Poland and Hungary, against the Ottoman Empire during the Crusade of Varna in 1444. Although Vlad II Dracul believed his sons would be "butchered for the sake of Christian peace," neither Vlad nor Radu was murdered or mutilated following their father's rebellion. This period of captivity in the Ottoman Empire, where they were educated in logic, Islam, and the Turkish language, is believed to have deeply influenced Vlad's later actions and his profound hatred for the Ottomans, the Janissaries, and even his brother Radu, who converted to Islam and befriended Mehmed II, the future Sultan. Vlad also harbored resentment towards his father for handing them over as hostages and for his perceived favoritism towards his half-brothers.

1.3. Father's Death and Exile

Between 1446 and 1447, Vlad II Dracul once again acknowledged the Sultan's suzerainty and pledged to pay a yearly tribute. However, John Hunyadi, who had become the regent-governor of Hungary in 1446, invaded Wallachia in November 1447. During this invasion, Vlad II Dracul and his eldest son, Mircea, were murdered. The Byzantine historian Michael Critobulus noted that Vlad and Radu fled to the Ottoman Empire, suggesting they had been allowed to return to Wallachia after their father's renewed homage to the Sultan. Hunyadi subsequently installed Vladislav II, a son of Vlad Dracul's cousin Dan II, as the new ruler of Wallachia.

Following his father's death, Vlad became a potential claimant to the Wallachian throne. After his brief first reign in 1448, he was forced to flee to the Ottoman Empire. He then moved to Moldavia around 1449 or 1450, seeking refuge with Bogdan II, his father's brother-in-law and possibly his maternal uncle, who had ascended to the Moldavian throne with John Hunyadi's support. When Bogdan II was assassinated by Peter III Aaron in October 1451, Bogdan's son, Stephen, fled to Transylvania with Vlad to seek assistance from Hunyadi. However, Hunyadi had just concluded a three-year truce with the Ottoman Empire, recognizing the Wallachian boyars' right to elect Vladislav II's successor. Vlad's attempts to settle in Brașov, a center for Wallachian boyars expelled by Vladislav II, were thwarted by Hunyadi, who forbade the burghers from offering him shelter. Vlad returned to Moldavia, where Alexăndrel had dethroned Peter Aaron. His movements during the following years are largely unknown, but he returned to Hungary before July 3, 1456, when Hunyadi assigned him the task of defending the Transylvanian border.

2. Reigns and Political Activities

Vlad III's rule in Wallachia was characterized by repeated struggles for the throne, a fierce determination to consolidate power, and relentless conflict with both internal and external adversaries.

2.1. First Reign (1448)

Taking advantage of Vladislav II's absence, who was campaigning against the Ottoman Empire with John Hunyadi in September 1448, Vlad III invaded Wallachia with Ottoman support in early October. During this brief period, he was forced to accept the Ottoman capture and fortification of the Giurgiu fortress on the Danube. However, his rule was short-lived. Following the Ottoman defeat of Hunyadi's army in the Battle of Kosovo in mid-October, Vladislav II returned to Wallachia with the remnants of his forces. Vlad was compelled to flee back to the Ottoman Empire by December 7, 1448. He had refused to meet Hunyadi's deputy, Nicholas Vízaknai, stating that such a meeting would endanger both of them due to the Ottoman victory.

2.2. Second Reign (1456-1462)

Vlad's second reign, from 1456 to 1462, was his most significant and established his reputation as a ruthless yet effective ruler.

Vlad invaded Wallachia with Hungarian support in 1456, the exact month being uncertain (April, July, or August). Vladislav II was killed during this invasion. By September 10, Vlad had sent his first letter as Voivode of Wallachia to the burghers of Brașov, promising protection against an Ottoman invasion of Transylvania and seeking their aid if Wallachia itself was occupied. In this letter, he articulated his authoritarian philosophy, stating that "when a man or a prince is strong and powerful he can make peace as he wants to; but when he is weak, a stronger one will come and do what he wants to him."

At the beginning of his reign, Vlad initiated a brutal purge against the boyars, particularly those he suspected of involvement in the murders of his father and elder brother, or those he believed were plotting against him. Multiple sources, including Laonikos Chalkokondyles's chronicle, record hundreds or even thousands of executions during this period. Chalkokondyles noted that Vlad "quickly effected a great change and utterly revolutionized the affairs of Wallachia" by confiscating the "money, property, and other goods" of his victims and redistributing them to his loyal retainers. This radical restructuring of the Wallachian aristocracy is evident in the princely council lists, which show that only two members retained their positions between 1457 and 1461.

2.2.1. Conflict with the Saxons

Vlad sent the customary tribute to the Ottoman Sultan. However, relations with the Transylvanian Saxons quickly deteriorated. After John Hunyadi's death in August 1456, his son Ladislaus Hunyadi became Hungary's captain-general and accused Vlad of disloyalty, ordering the burghers of Brașov to support Dan III, Vladislav II's brother, against Vlad. The burghers of Sibiu supported another pretender, identified as Vlad's illegitimate half-brother, Vlad Călugărul, who took possession of Amlaș, a traditional Wallachian fief in Transylvania.

Taking advantage of the civil war in Hungary following the execution of Ladislaus Hunyadi in March 1457, Vlad assisted Stephen, son of Bogdan II of Moldavia, in seizing Moldavia in June 1457. Vlad also invaded Transylvania, plundering villages around Brașov and Sibiu. Early German accounts describe him taking "men, women, children" from a Saxon village to Wallachia and having them impaled. These attacks against the Saxons, who remained loyal to the Hungarian king, inadvertently strengthened the position of the Szilágyi family, who were rebelling against the king.

Vlad's representatives participated in peace negotiations between Michael Szilágyi and the Saxons. The burghers of Brașov agreed to expel Dan III from their town. Vlad promised free trade for Sibiu merchants in Wallachia in exchange for reciprocal treatment of Wallachian merchants in Transylvania. Vlad addressed Michael Szilágyi as his "Lord and elder brother" in a letter from December 1, 1457.

When Matthias Corvinus was elected King of Hungary in January 1458, he ordered Sibiu to maintain peace with Vlad. By September 20, 1459, Vlad styled himself "Lord and ruler over all of Wallachia, and the duchies of Amlaș and Făgăraș," indicating his full control over these Transylvanian fiefs. Despite a brief period of cooperation, relations with the Saxons worsened. A scholarly theory suggests this conflict arose after Vlad forbade Saxons from entering Wallachia, forcing them to sell goods at compulsory border fairs, though this is not documented. Vlad himself later emphasized his support for free trade.

The conflict escalated when Saxons confiscated steel bought by a Wallachian merchant in Brașov. In retaliation, Vlad "ransacked and tortured" some Saxon merchants. Dan III, supported by Matthias Corvinus and residing in Brașov, claimed Vlad had impaled or burned alive Saxon merchants and their children in Wallachia. Basarab Laiotă, another claimant, also settled in Sighișoara and accused Vlad of impaling 41 merchants and 300 boys from Brașov and Țara Bârsei, accusing him of siding with the Ottomans.

Dan III invaded Wallachia but was defeated and executed by Vlad before April 22, 1460. Vlad then invaded southern Transylvania, destroying the suburbs of Brașov and ordering the impalement of all captured men and women. During subsequent negotiations, Vlad demanded the expulsion or punishment of all Wallachian refugees from Brașov. Peace was restored by July 26, 1460, when Vlad addressed the burghers of Brașov as "brothers and friends." On August 24, he invaded the regions of Amlaș and Făgăraș to punish locals who had supported Dan III.

2.2.2. Ottoman War

Konstantin Mihailović, a janissary in the Sultan's army, recorded that Vlad refused to pay homage to the Sultan at an unspecified time. Renaissance historian Giovanni Maria Angiolello similarly wrote that Vlad had failed to pay tribute to the Sultan for three years. These accounts suggest Vlad ignored the suzerainty of Mehmed II as early as 1459, though both works were written decades after the events. Tursun Beg, a secretary in the Sultan's court, stated that Vlad only turned against the Ottoman Empire when the Sultan was on a long expedition in Trebizond in 1461. According to Tursun Beg, Vlad initiated new negotiations with Matthias Corvinus, but the Sultan's spies soon informed him.

Mehmed II sent his envoy, the Greek Thomas Katabolinos (also known as Yunus Bey), to Wallachia, ordering Vlad to come to Constantinople. Secret instructions were also sent to Hamza, Bey of Nicopolis, to capture Vlad after he crossed the Danube. Vlad discovered the Sultan's "deceit and trickery," captured Hamza and Katabolinos, and had them executed by impalement.

After executing the Ottoman officials, Vlad, speaking fluent Turkish, ordered the commander of the Giurgiu fortress to open its gates, allowing Wallachian soldiers to capture it. He then invaded Ottoman territory, devastating villages along the Danube. In a letter to Matthias Corvinus on February 11, 1462, Vlad reported killing over "23,884 Turks and Bulgarians" during the campaign. He sought military assistance from Corvinus, declaring his actions were "for the honor" of the King and the Holy Crown of Hungary, and "for the preservation of Christianity and the strengthening of the Catholic faith." By 1462, relations between Moldavia and Wallachia had become tense, as noted by the Genoese governor of Kaffa. Many commoners and nobles of Romania and Bulgaria also moved north of the Danube to Wallachia, acknowledging Vlad's leadership and settling there after his raids against the Ottomans.

Upon learning of Vlad's invasion, Mehmed II raised an army of over 150,000 men, a force said to be second in size only to the one that occupied Constantinople in 1453, according to Chalkokondyles. Historians interpret the size of this army as indicating the Sultan's intent to occupy Wallachia. However, Mehmed had already granted Wallachia to Vlad's younger brother, Radu, before the invasion, suggesting the Sultan's primary goal was to replace the ruler.

The Ottoman fleet landed at Brăila, Wallachia's only port on the Danube, in May 1462. The main Ottoman army, led by the Sultan, crossed the Danube at Nikopol, Bulgaria on June 4, 1462. Outnumbered, Vlad adopted a scorched earth policy, retreating towards Târgoviște. During the night of June 16-17, Vlad launched a night attack on the Ottoman camp, attempting to capture or kill the Sultan. The goal was to cause panic and enable a Wallachian victory. However, the Wallachians "missed the court of the sultan himself" and instead attacked the tents of the viziers Mahmud Pasha and Isaac. Failing to achieve their primary objective, Vlad and his retainers withdrew at dawn.

Mehmed entered Târgoviște at the end of June. The town was deserted, but the Ottomans were horrified to discover a "forest of the impaled"-thousands of stakes bearing the carcasses of executed people, including infants affixed to their mothers. Chalkokondyles described the scene as seventeen stades long and seven stades wide, causing amazement and fear among the Turks and the Sultan, who remarked that it was impossible to defeat a man who had done such great deeds and possessed such a diabolical understanding of governance.

Tursun Beg recorded that the Ottomans suffered from summer heat and thirst during the campaign. The Sultan decided to retreat from Wallachia and marched towards Brăila. Meanwhile, Stephen III of Moldavia hurried to Chilia (now Kiliya in Ukraine) to seize the important fortress held by a Hungarian garrison. Vlad also set out for Chilia, leaving a force of 6,000 to hinder the Sultan's army, but they were defeated. Stephen of Moldavia was wounded during the siege of Chilia and returned to Moldavia before Vlad arrived.

The main Ottoman army left Wallachia, but Vlad's brother Radu and his Ottoman troops remained in the Bărăgan Plain. Radu sent messengers to the Wallachians, reminding them of the Sultan's potential return. Although Vlad defeated Radu and his Ottoman allies in two subsequent battles, more and more Wallachians deserted to Radu's side. Vlad retreated to the Carpathian Mountains, hoping for assistance from Matthias Corvinus. However, Albert of Istenmező, the deputy of the Count of the Székelys, recommended that the Saxons recognize Radu. Radu also offered the burghers of Brașov confirmation of their commercial privileges and a compensation of 15,000 ducats.

2.3. Imprisonment in Hungary (1462-1475)

Matthias Corvinus arrived in Transylvania in November 1462. Negotiations between Corvinus and Vlad lasted for weeks, but Corvinus was unwilling to wage war against the Ottoman Empire. By the King's order, his Czech mercenary commander, John Jiskra of Brandýs, captured Vlad near Rucăr in Wallachia.

To justify Vlad's imprisonment to Pope Pius II and the Republic of Venice (who had provided funds for a campaign against the Ottoman Empire), Corvinus presented three letters, allegedly written by Vlad on November 7, 1462, to Mehmed II, Mahmud Pasha, and Stephen of Moldavia. These letters purportedly showed Vlad offering to join forces with the Sultan's army against Hungary if the Sultan restored him to his throne. Most historians agree that these documents were forged to provide grounds for Vlad's capture. Corvinus's court historian, Antonio Bonfini, admitted that the reason for Vlad's imprisonment was never fully clarified. Florescu notes that the "style of writing, the rhetoric of meek submission (hardly compatible with what we know of Dracula's character), clumsy wording, and poor Latin" all suggest the letters were not written by Vlad, associating the forgery with a Saxon priest from Brașov.

Vlad was initially imprisoned in "the city of Belgrade" (now Alba Iulia in Romania), according to Chalkokondyles. Soon after, he was transferred to Visegrád, where he was held for fourteen years. No documents referring to Vlad between 1462 and 1475 have been preserved. In the summer of 1475, Stephen III of Moldavia sent envoys to Matthias Corvinus, requesting Vlad's release to be sent to Wallachia against Basarab Laiotă, who had submitted to the Ottomans. Stephen desired a ruler in Wallachia who was an enemy of the Ottoman Empire, stating that "the Wallachians [were] like the Turks" to the Moldavians. According to Slavic accounts about Vlad, he was only released after converting to Catholicism. During his imprisonment, anecdotes about his cruelty, such as catching rats and impaling them, began to spread.

2.4. Third Reign and Death (1476-1477)

Matthias Corvinus recognized Vlad as the lawful prince of Wallachia but did not provide him with military assistance to regain his principality. Vlad settled in Pest and later moved to Transylvania in June 1475, seeking a residence in Sibiu. Mehmed II, meanwhile, acknowledged Basarab Laiotă as the legitimate ruler of Wallachia. Despite Corvinus ordering the burghers of Sibiu to give Vlad 200 golden florins in September, Vlad left Transylvania for Buda in October.

Vlad purchased a house in Pécs that became known as Drakula háza ("Dracula's house" in Hungarian). In January 1476, John Pongrác of Dengeleg, Voivode of Transylvania, urged the people of Brașov to send Vlad's supporters who had settled in the town back to him, as Corvinus and Basarab Laiotă had concluded a treaty. However, relations between the Transylvanian Saxons and Basarab remained tense, and the Saxons continued to shelter Basarab's opponents.

In early 1476, Corvinus dispatched Vlad and the Serbian Vuk Grgurević to fight against the Ottomans in Bosnia. They captured Srebrenica and other fortresses in February and March 1476. In this Bosnian campaign, Vlad once again employed his terror tactics, mass impaling captured Turkish soldiers and massacring civilians in conquered settlements, destroying Srebrenica, Kuslat, and Zvornik.

Mehmed II invaded Moldavia and defeated Stephen III in the Battle of Valea Albă on July 26, 1476. Stephen Báthory and Vlad then entered Moldavia, forcing the Sultan to lift the siege of the fortress at Târgu Neamț in late August. Matthias Corvinus ordered the Transylvanian Saxons to support Báthory's planned invasion of Wallachia on September 6, 1476, also informing them that Stephen of Moldavia would join the invasion. Vlad stayed in Brașov and confirmed the commercial privileges of the local burghers in Wallachia on October 7, 1476.

Báthory's forces captured Târgoviște on November 8. Stephen of Moldavia and Vlad ceremoniously confirmed their alliance and occupied Bucharest, forcing Basarab Laiotă to seek refuge in the Ottoman Empire on November 16. Vlad informed the merchants of Brașov about his victory, urging them to come to Wallachia, and was crowned before November 26.

However, Basarab Laiotă returned to Wallachia with Ottoman support. Vlad III died fighting against them in late December 1476 or early January 1477. Stephen III of Moldavia, in a letter dated January 10, 1477, reported that Vlad's Moldavian retinue had also been massacred. According to reliable sources, Vlad's army of about 2,000 was cornered and destroyed by a Turkish-Basarab force of 4,000 near Snagov. During this period, he spent much of his time in Snagov Church, attending mass daily and conversing with the abbot, and even asked if his sins could be forgiven, requesting to be buried in that church.

The exact circumstances of his death remain unclear. The Austrian chronicler Jacob Unrest stated that a disguised Turkish assassin murdered Vlad in his camp. In contrast, Russian statesman Fyodor Kuritsyn, who interviewed Vlad's family after his demise, reported that the voivode was mistaken for a Turk by his own troops during battle, causing them to attack and kill him. Historians Florescu and Raymond T. McNally noted that Vlad had often disguised himself as a Turkish soldier as part of military ruses. Leonardo Botta, the Milanese ambassador to Buda, reported that the Ottomans cut Vlad's corpse into pieces. Bonfini wrote that Vlad's head was sent to Mehmed II, where it was eventually placed on a high stake in Constantinople. His severed head was allegedly displayed and buried in Voivode Street (today Bankalar Caddesi) in Karaköy, with Voyvoda Han rumored to be its final resting place. Local peasant traditions maintain that what remained of Vlad's corpse was later discovered in the marshes of Snagov by monks from the nearby monastery. However, the place of his burial is unknown. Excavations in 1933 at the Monastery of Snagov, a popular traditional burial site, found no tomb below Vlad's supposed "unmarked tombstone," only "many bones and jaws of horses." Historian Constantin Rezachevici suggests Vlad was most probably buried in the first church of the Comana Monastery, which he had established and was near the battlefield where he was killed.

3. Military Campaigns and Diplomacy

Vlad III's military and diplomatic efforts were primarily focused on consolidating his rule within Wallachia and resisting the formidable expansion of the Ottoman Empire.

3.1. Wars with the Ottoman Empire

Vlad's most significant military engagements were his relentless wars against the Ottoman Empire. He refused to pay the increased tribute of 10,000 ducats demanded by Mehmed II and executed Ottoman envoys who insisted on his personal homage, nailing their turbans to their heads as a sign of disrespect. In February 1462, he launched a preemptive strike into Ottoman territory, devastating villages along the Danube and reportedly massacring tens of thousands of Turks and Muslim Bulgarians. This bold act prompted Mehmed II to lead a massive invasion of Wallachia with an army exceeding 150,000 troops.

Outnumbered, Vlad employed a scorched earth policy, poisoning wells and destroying crops to deny the Ottomans resources as they advanced towards Târgoviște. His most famous military action was the Night Attack at Târgoviște on June 16-17, 1462, where he attempted to assassinate or capture Sultan Mehmed II within his own camp. Although the attack failed to kill the Sultan, it caused significant casualties and psychological impact on the Ottoman forces, who mistakenly attacked the tents of viziers. Upon entering Târgoviște, the Ottomans were confronted by the horrific "forest of the impaled," a sight that reportedly caused Mehmed II to remark on Vlad's formidable and "diabolical" understanding of governance. Despite initial successes, Vlad's forces were eventually overwhelmed, and he was forced to retreat as more Wallachians defected to his brother Radu, who was supported by the Ottomans. Vlad sought assistance from Matthias Corvinus of Hungary, but this resulted in his imprisonment.

3.2. Conflicts with Transylvanian Saxons

Vlad's rule also saw frequent and often brutal conflicts with the Transylvanian Saxon communities. These disputes primarily stemmed from trade disagreements and the Saxons' support for rival claimants to the Wallachian throne, such as Dan III and Basarab Laiotă. Vlad accused the Saxons of unfair trade practices and harboring his enemies. In retaliation, he launched punitive raids into Transylvanian Saxon territories, plundering villages and carrying off captives to Wallachia, where he subjected them to mass impalements. These acts were widely documented in German pamphlets, contributing significantly to his reputation for cruelty. A notable instance involved Vlad's invasion of southern Transylvania after defeating Dan III in 1460, where he destroyed the suburbs of Brașov and ordered the impalement of all captured men and women. Peace was eventually restored through negotiations, often involving demands for the expulsion of Wallachian refugees from Saxon towns.

4. Methods of Rule and Law Enforcement

Vlad III's governance was characterized by an exceptionally severe approach to law enforcement and a deliberate use of terror to centralize power and maintain order.

4.1. The Use of Impalement

Impalement was Vlad III's signature method of execution and punishment, applied with a frequency and scale that earned him his infamous epithet. This gruesome practice involved driving a large stake through the victim's body, often from the rectum or vagina, until it emerged from the mouth, chest, or shoulder, ensuring a slow and agonizing death. The stakes were then erected vertically, leaving the victims to die exposed. Vlad employed impalement not only against captured Ottoman soldiers and foreign merchants but also against Wallachian boyars, criminals, and even ordinary citizens who defied his authority or failed to meet his strict standards.

The purpose of impalement under Vlad's rule was multifaceted: it served as a brutal deterrent against crime and disloyalty, a means of eliminating political rivals, and a psychological weapon against invading armies. The sight of thousands of impaled bodies, as witnessed by the Ottoman army at Târgoviște, was intended to instill terror and break the enemy's morale.

4.2. Consolidation of Power through Terror

Vlad III systematically utilized harsh punishments and terror tactics to centralize authority, suppress internal opposition, and enforce his rule. Upon regaining his throne in 1456, he initiated a purge against the boyars, whom he suspected of complicity in his father's and brother's murders or of plotting against him. He confiscated their wealth and redistributed it to his loyal retainers, effectively replacing the old aristocracy with a new, subservient elite.

His methods extended to all segments of society. Legends describe how he would invite prominent nobles to banquets only to have them impaled, or how he gathered the poor, sick, and Roma people into a building and set it ablaze to eliminate perceived burdens on society. Another anecdote recounts a golden cup placed in a public fountain, which no one dared to steal due to the severe punishments for theft, demonstrating his success in establishing public order through fear. These acts, whether historical or legendary, illustrate his ruthless determination to establish absolute control and eliminate any challenge to his authority.

4.3. Origin of the Epithet "Vlad the Impaler"

Vlad III's notorious method of execution directly led to his widely recognized epithet, "Vlad the Impaler" (Vlad ȚepeșRomanian). This moniker, meaning "the Impaler" or "the Stake-Driver," became synonymous with his rule. The Ottoman writer Tursun Beg referred to him as Kazıklı VoyvodaTurkish, Ottoman (Latin script) (Impaler Lord) around 1500, indicating that his method of punishment was well-known even to his adversaries. The sobriquet was later used by Wallachian Voivode Mircea the Shepherd in a letter from 1551, solidifying its place in historical record. While impalement was not unique to Vlad's era, his extensive and indiscriminate use of it, particularly against nobles (who were typically beheaded), made his application of the punishment distinct and earned him this lasting, fearsome title.

5. Personal Life

Details about Vlad III's personal life are scarce, but historical accounts provide some insight into his marriages and children.

5.1. Marriages and Children

Modern historians suggest Vlad III had two wives. His first wife may have been an illegitimate daughter of John Hunyadi, according to historian Alexandru Simon. His second wife was Justina Szilágyi, a cousin of Matthias Corvinus. She was the widow of Vencel Pongrác of Szentmiklós when she married Vlad, most likely in 1475. She survived Vlad III and later married Pál Suki and then János Erdélyi.

Vlad's eldest son, Mihnea, was born in 1462. His unnamed second son was killed before 1486. Vlad's third son, Vlad Drakwlya, unsuccessfully claimed the Wallachian throne around 1495 and was the forefather of the noble Drakwla family in Hungary.

6. Legacy and Historical Evaluation

Vlad III's legacy is complex and contradictory, ranging from a national hero in Romania to a figure of unparalleled cruelty in Western folklore.

6.1. Reputation for Cruelty

Stories about Vlad's brutal acts began circulating during his lifetime, particularly after his arrest in 1462, promoted by the courtiers of Matthias Corvinus. The papal legate, Niccolo Modrussiense, wrote about these stories to Pope Pius II in 1462, and the Pope included them in his Commentaries two years later. It was even rumored that Vlad once dipped his bread into the blood of his impaled victims, though this remains a legend.

Meistersinger Michael Beheim wrote a lengthy poem, Von ainem wutrich der heis Trakle waida von der WalacheiGerman ("Story of a Despot Called Dracula, Voievod of Wallachia"), performed at the court of Frederick III, Holy Roman Emperor, in Wiener Neustadt in 1463. Beheim's poem, based on a monk's account, depicted Vlad's cruelty, including impaling two monks and their braying donkey. He also accused Vlad of duplicity towards Matthias Corvinus and Mehmed II.

In 1475, Gabriele Rangone, Bishop of Eger, understood Vlad's imprisonment was due to his cruelty. Rangone also recorded the rumor that Vlad, while imprisoned, would catch rats and cut them into pieces or impale them on small pieces of wood, unable to "forget his wickedness." Antonio Bonfini's Historia Pannonica (c. 1495) also recorded anecdotes about Vlad, describing him as "a man of unheard cruelty and justice," aiming to justify both his removal and restoration by Matthias. Bonfini's stories, including the one about Vlad nailing the turbans of Ottoman messengers to their heads for their refusal to remove them, were repeated in Sebastian Münster's Cosmography, which also noted Vlad's "reputation for tyrannical justice."

6.1.1. German stories

Works containing stories about Vlad's cruelty were published in Low German in the Holy Roman Empire before 1480, becoming early "bestsellers" in Europe due to the invention of movable type. These stories, likely written in the early 1460s before Mehmed II's invasion of Wallachia, provide detailed narrations of conflicts between Vlad and the Transylvanian Saxons, suggesting their origin in Saxon literary circles. They describe Vlad as a "demented psychopath, a sadist, a gruesome murderer, a masochist," worse than Caligula and Nero. While some details, such as lists of destroyed churches and raid dates, suggest eyewitness accounts, historians caution that Vlad's brutal acts were likely exaggerated or invented by the Saxons. To boost sales, these books featured horrific woodcuts on their title pages, depicting scenes like Vlad dining among impaled victims. One anecdote describes Vlad boiling people in a cauldron and impaling women with their suckling babies.

6.1.2. Slavic stories

Over 20 manuscripts from the 15th to 18th centuries preserve the text of the Skazanie o Drakule voievode ("The Tale about Voivode Dracula"). Written in Russian but based on a South Slavic original, these anecdotes are longer than the German stories and mix fact with fiction. Almost half of them, like the German accounts, emphasize Vlad's brutality but crucially underline that his cruelty enabled him to strengthen the central government in Wallachia. For example, the Skazanie recounts a golden cup at a fountain that no one dared to steal because Vlad "hated stealing so violently... that anybody who caused any evil or robbery... did not live long," thereby promoting public order. While German stories focused on his cruel acts in the Ottoman campaign, the Skazanie emphasized his successful diplomacy, calling him "zlomudry" or "evil-wise." However, the Skazanie sharply criticized Vlad for his conversion to Catholicism, attributing his death to this apostasy. Some elements of these anecdotes were later incorporated into Russian stories about Ivan the Terrible.

6.1.3. Assertion by modern standards

By current standards, the mass murders carried out indiscriminately and brutally under Vlad III's command would most likely amount to acts of genocide and war crimes. Former Romanian defense minister Ioan Mircea Pașcu asserted that Vlad would have been condemned for crimes against humanity had he been put on trial at Nuremberg. Research published in 2023, based on analysis of samples from letters written by Vlad, suggests he may have suffered from haemolacria, a rare condition causing tears to be partially composed of blood.

6.2. National Hero of Romania

In Romania, Vlad III is widely regarded as a national hero, primarily for his role in defending Wallachia against the Ottoman Empire and for his efforts to consolidate the state. The Cantacuzino Chronicle was the first Romanian historical work to record a tale about Vlad the Impaler, narrating the impalement of the old boyars of Târgoviște for the murder of his brother, Dan. The chronicle added that Vlad forced the young boyars and their families to build the Poenari Castle. The legend of Poenari Castle was further popularized by Neofit I, Metropolitan of Ungro-Wallachia, in 1747, who connected it to the story of Meșterul Manole, a legendary master builder. Local legends also recount Vlad's "rabbit skin" letter of grant for villagers who helped him escape Poenari Castle during the Ottoman invasion, though some attribute this to the legendary Radu Negru.

Further local legends, some mirroring German and Slavic stories, suggest the preservation of oral traditions. These tales, such as the burning of the lazy, poor, and lame, or the execution of a woman who made her husband too short a shirt, were known by peasants who, despite acknowledging his cruel impalements, believed such acts were necessary to maintain public order in Wallachia.

Most Romanian artists have portrayed Vlad as a just ruler and a pragmatic tyrant who punished criminals and executed unpatriotic boyars to strengthen the central government. Ion Budai-Deleanu wrote the first Romanian epic poem about him, Țiganiada (Gypsy Epic), which depicted Vlad as a hero fighting against boyars, Ottomans, strigoi (vampires), and other evil spirits. The poet Dimitrie Bolintineanu emphasized Vlad's triumphs in his mid-19th-century Battles of the Romanians, viewing his violence as necessary to prevent boyar despotism. Mihai Eminescu, a prominent Romanian poet, dedicated a historic ballad, The Third Letter, to Wallachia's valiant princes, including Vlad, urging his return to annihilate the enemies of the Romanian nation. In the early 1860s, painter Theodor Aman depicted the meeting of Vlad and the Ottoman envoys, highlighting the envoys' fear of the Wallachian ruler.

Since the mid-19th century, Romanian historians have largely regarded Vlad as one of Romania's greatest rulers, emphasizing his fight for the independence of Romanian lands. Even his acts of cruelty were often rationalized as serving the national interest. Alexandru Dimitrie Xenopol argued that Vlad's terror tactics were necessary to end the internal conflicts of boyar factions. Constantin C. Giurescu stated that Vlad's "tortures and executions... always had a reason, and very often a reason of state." However, Ioan Bogdan was one of the few Romanian historians who did not embrace this heroic image, concluding in his 1896 work Vlad Țepeș and the German and Russian Narratives that Romanians should be ashamed of Vlad rather than presenting him as "a model of courage and patriotism." An opinion poll in 1999 revealed that 4.1% of Romanians considered Vlad the Impaler among "the most important historical personalities who have influenced the destiny of the Romanians for the better."

6.3. Criticism and Modern Assessment

Despite his heroic status in Romania, Vlad III's brutal actions have faced significant criticism from contemporary and modern perspectives. His widespread and indiscriminate use of impalement, massacres of civilians, and other cruel punishments have led to modern assessments that his actions would constitute war crimes and genocide by current international legal standards. Critics argue that regardless of the political context or perceived necessity, the extreme nature of his violence, including the torture and murder of non-combatants, violates fundamental human rights. The ethical implications of his rule are debated, with some historians acknowledging his effectiveness in consolidating power and defending his realm, while others condemn his methods as excessively cruel and inhumane, highlighting the moral cost of his authoritarianism.

6.4. Inspiration for Vampire Mythology

The stories about Vlad III's cruelty made him the most well-known medieval ruler of the Romanian lands in Europe. However, it was Bram Stoker's 1897 novel Dracula that first explicitly connected the name Dracula with vampirism. Stoker was reportedly drawn to the concept of blood-sucking vampires from Romanian folklore through Emily Gerard's 1885 article on Transylvanian superstitions. His limited knowledge of Wallachian medieval history came primarily from William Wilkinson's 1820 book, Account of the Principalities of Wallachia and Moldavia with Political Observations Relative to Them.

According to academic Elizabeth Miller, Stoker "apparently did not know much about" Vlad the Impaler, "certainly not enough for us to say that Vlad was the inspiration for" Count Dracula. For instance, Stoker's depiction of Dracula as being of Székely origin was likely influenced by his knowledge of Attila the Hun's campaigns and the alleged Hunnic origin of the Székelys. Wilkinson, Stoker's main source, described Vlad as a wicked man, aligning with the German stories that emphasized his cruelty. Stoker's working papers for his novel contain no direct references to the historical Vlad, with the character initially named "Count Wampyr" in early drafts. Consequently, Stoker is believed to have borrowed only Vlad's name and "scraps of miscellaneous information" about Wallachian history for his fictional Count Dracula. The historical Vlad III never drank blood, and even his Ottoman enemies never described him as a blood-sucking creature. Some modern theories, however, suggest Vlad III may have suffered from haemolacria (crying tears of blood) or porphyria, which could have caused light sensitivity and pale skin, leading to later associations with vampiric traits.

The connection between Vlad III and the fictional vampire has led to various "Dracula castles." While Bran Castle is popularly known as "Dracula's Castle," it was built by the Teutonic Knights, and Vlad III's grandfather, Mircea I, resided there in the 14th century. Vlad himself only stayed there briefly. His actual main residence and palace were in Târgoviște, the capital of Wallachia. Poenari Castle is also associated with Vlad, though Stoker reportedly had no knowledge of it. Some scholars suggest Stoker's inspiration for the castle in his novel came from New Slains Castle in Scotland, which he had visited.

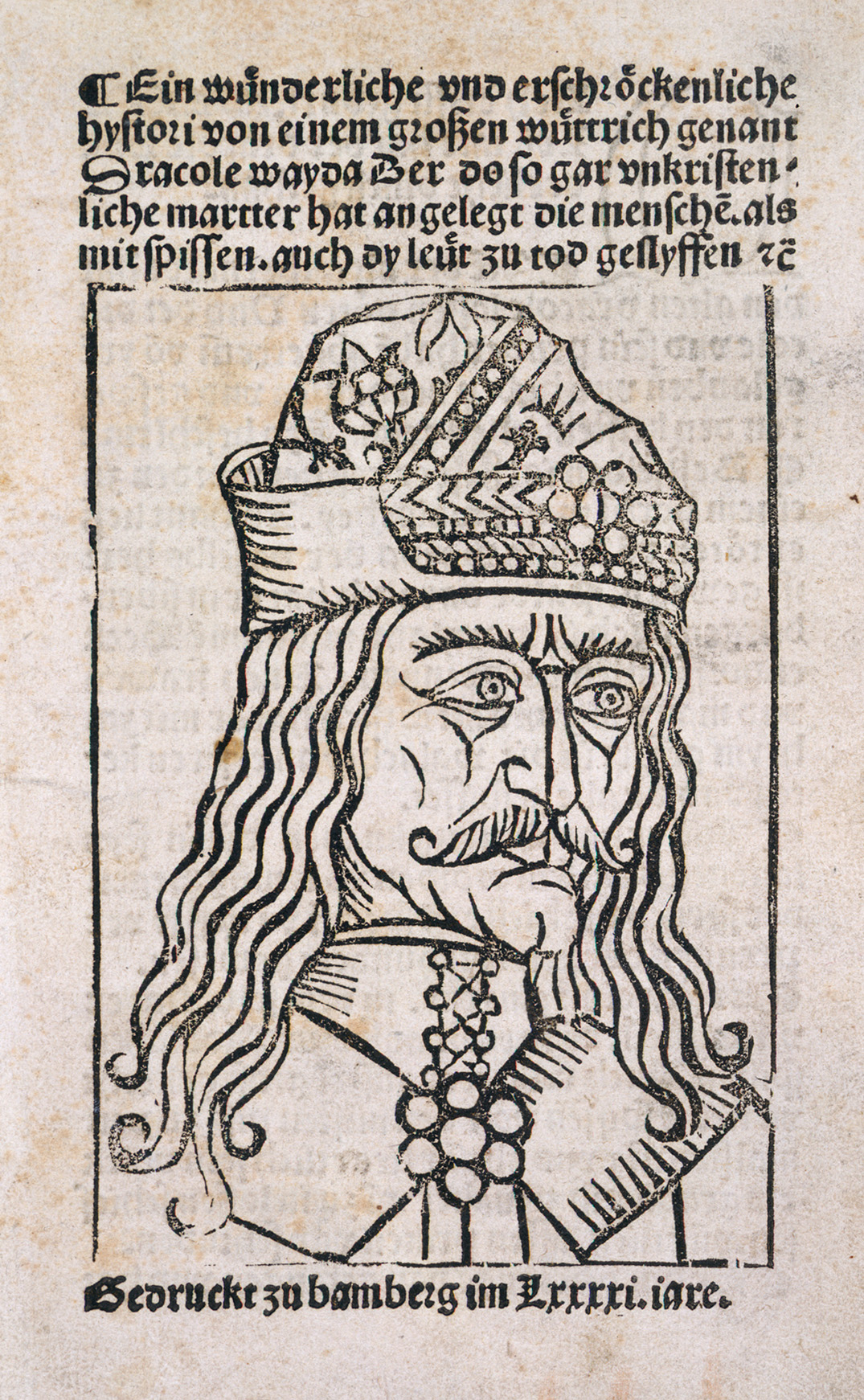

7. Appearance and Depictions

The only extant description of Vlad III from his lifetime comes from Niccolò Modrussa, a legate of Pope Pius II, who met Vlad in Buda. Modrussa described Vlad as "not very tall, but very stocky and strong, with a cold and terrible appearance, a strong and aquiline nose, swollen nostrils, a thin and reddish face in which the very long eyelashes framed large wide-open green eyes; the bushy black eyebrows made them appear threatening. His face and chin were shaven but for a moustache. The swollen temples increased the bulk of his head. A bull's neck connected [with] his head from which black curly locks hung on his wide-shouldered person."

A copy of Vlad's portrait is featured in the "monster portrait gallery" at Ambras Castle in Innsbruck. Florescu described this painting as depicting "a strong, cruel, and somehow tortured man" with "large, deep-set, dark green, and penetrating eyes." The color of Vlad's hair is uncertain, as Modrussa mentioned him as black-haired, while the portrait appears to show fair hair. The picture also depicts Vlad with a large lower lip.

Vlad's negative reputation in German-speaking territories is reflected in several Renaissance paintings. He was portrayed among the witnesses of Saint Andrew's martyrdom in a 15th-century painting displayed in the Belvedere in Vienna. A figure resembling Vlad is also depicted as one of the witnesses of Christ in the Calvary in a chapel of the St. Stephen's Cathedral in Vienna. His likeness was also found in a 1460 painting of "Calvary of Christ" in Maria am Gestade, Vienna, and in "Pilate Judging Jesus Christ" from 1463 in the National Gallery of Slovenia in Ljubljana. A 17th-century full-size portrait of Vlad Țepeș is part of the "Gallery of Ancestors" of the House of Esterházy at Forchtenstein Castle. Woodcuts and engravings from the late 15th century, such as those published in Nuremberg (1488, 1499) and Bamberg (1491), further disseminated his image, often depicting him engaged in acts of impalement.