1. Overview

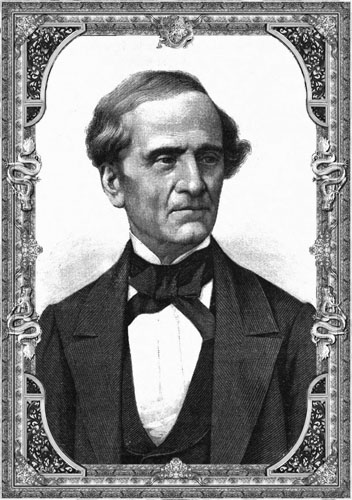

Valentín Gómez Farías (Valentín Gómez Faríasbalenˈtiŋ ˈɡomes faˈɾiasSpanish; 14 February 1781 - 5 July 1858) was a prominent Mexican liberal politician and physician who served multiple times as the President of Mexico, first from 1833 to 1834, and again from 1846 to 1847. He is remembered as a pioneering figure of Mexican liberalism, championing radical reforms aimed at diminishing the entrenched power and privileges of the Catholic Church and the Mexican Army. His presidencies were marked by ambitious secularizing initiatives, including the abolition of tithes and the secularization of education, which ignited significant conservative backlash and political instability. Despite facing repeated overthrows and periods of exile, Gómez Farías persistently advocated for a federal republic and played a crucial role in the drafting of the liberal Constitution of 1857, ensuring the incorporation of many of the reforms he had long championed. His career reflects the turbulent transition of Mexico from a colonial society to an independent nation, deeply divided between liberal and conservative ideologies.

2. Early Life and Education

Valentín Gómez Farías' early life was shaped by his upbringing in Guadalajara and his medical studies, which exposed him to the influential ideas of the Age of Enlightenment. This period laid the groundwork for his future political career as a staunch liberal reformer.

2.1. Childhood and Education

Valentín Gómez Farías was born in Guadalajara, Jalisco, then part of the New Kingdom of Galicia in New Spain, on 14 February 1781. He pursued his higher education in the same city, enrolling at the Royal University of Guadalajara to study medicine. During his studies, he acquired proficiency in French, which allowed him to clandestinely access and read influential works from the Age of Enlightenment that were circulating throughout New Spain. His academic dissertation displayed such a strong influence from Enlightenment authors that it drew the attention of the Mexican Inquisition. However, no legal action was ultimately taken against him, and he successfully established a medical practice in Guadalajara. On 17 October 1817, he married Isabel López in Aguascalientes.

2.2. Early Political Career

Gómez Farías embarked on his political career following Mexico's independence from Spain. In 1821, after Agustín de Iturbide achieved Mexican Independence through the Plan of Iguala and established the nation as a monarchy, Gómez Farías was elected to the congress tasked with drafting a constitution. Initially, he supported Iturbide, even delivering a speech in congress defending the legality of electing Iturbide as Emperor. However, his support waned as Iturbide grew increasingly autocratic, viewing himself as sovereign over the congress and eventually dissolving the body. This led Gómez Farías, a staunch liberal who expected a constitutional monarchy, to turn against the emperor.

After the collapse of the First Mexican Empire in 1823, Gómez Farías actively supported the successful presidential candidacy of Guadalupe Victoria, who became Mexico's first president. Later, during the liberal presidency of Vicente Guerrero, Gómez Farías was offered the position of Minister of the Treasury after Lorenzo de Zavala resigned, but he declined the post at that time. When Antonio López de Santa Anna initiated the Plan of Veracruz in 1832 against the conservative President Anastasio Bustamante, Gómez Farías played a role in convincing Governor Garcia of Zacatecas to align with the rebels. This rebellion led to Bustamante's overthrow. Following this, Gómez Farías supported the candidacy of Manuel Gómez Pedraza, who assumed the presidency until the next scheduled elections. Pedraza appointed Gómez Farías as his Minister of the Treasury from 2 February to 31 March 1833.

3. Political Ideology and Reform Agenda

Valentín Gómez Farías was a fervent advocate of liberalism in Mexico, driven by a deep commitment to modernizing the nation and curtailing the significant influence of the Catholic Church and the Mexican Army. His core political philosophy centered on creating a secular state, promoting individual liberties, and fostering social progress. He believed that the Church and military, with their extensive landholdings, wealth, and legal privileges, constituted major obstacles to Mexico's development and democratic governance.

His reform agenda, which came to be known as the "Reform Laws" (or "Reformas" in Spanish), aimed to dismantle the entrenched power of these institutions. Key components of his agenda included the abolition of mandatory tithes, the nationalization of church properties, the secularization of education, and the elimination of special legal exemptions (known as fueros) for clergy and military personnel, which allowed them to be tried in their own courts. He also sought to expand these reforms to the border provinces, such as Alta California, promoting legislation to secularize the Franciscan missions there and organizing non-missionary colonization efforts like the Híjar-Padrés colony in 1833. The colony's secondary objective was to help protect Alta California from Russian colonial ambitions emanating from trading posts like Fort Ross. Gómez Farías' vision was to establish a more equitable society, strengthen the federal system, and redirect national resources towards public education and the state, rather than allowing them to remain concentrated in privileged institutions. His radical approach laid the groundwork for future liberal movements in Mexico, most notably La Reforma decades later.

4. First Presidency (1833-1834)

Gómez Farías' first presidency was a pivotal period characterized by the bold implementation of his liberal reform agenda. Assuming the presidency in March 1833 alongside Antonio López de Santa Anna, Gómez Farías, as vice president, frequently took over the executive duties while Santa Anna was away or deliberately abstained, allowing the radical reforms to proceed. This period saw a significant confrontation with the powerful Catholic Church and the military, leading to widespread political and social unrest that ultimately resulted in his overthrow.

4.1. Anti-Clerical Measures

During Gómez Farías' first term, the press adopted an increasingly anti-clerical stance, portraying the clergy as worldly, greedy hypocrites and critiquing the Bible as a source of absurdities from an ignorant era. The authority of the Pope was also challenged, with progressives asserting that Mexican independence extended to freedom from papal influence, and accusing the clergy of being subject to a foreign power. Anti-clerical writers invoked speeches from the French Revolutionary Assembly to support their cause, and priests were subjected to government surveillance.

Minister Miguel Ramos Arizpe decreed that papal bulls and other papal proclamations could not be published in Mexico without government authorization. The State of Mexico, under Governor Lorenzo de Zavala, abolished the legal obligation to pay tithes. The Congress of Veracruz and other state legislatures passed decrees to seize the assets of religious communities, and the state of Veracruz went as far as suppressing all monasteries. This prompted concerns that the government intended to abolish all religion, leading Gómez Farías to issue a statement clarifying that he had no such intentions.

On 27 October 1833, a national measure was passed, officially lifting the legal obligation to pay tithes. While a commission of the chamber of deputies recommended nationalizing all church properties, this proposal did not become law. On 6 November 1833, the legal obligation to fulfill monastic vows was removed, granting monks and nuns the freedom to leave their religious communities. Despite this, most chose to remain. A significant measure, passed on 17 December 1833, granted the Mexican government the power to make appointments to the church hierarchy, known as the patronato. Previous appointments made without government approval were declared nullified.

In October 1833, clergy were prohibited from teaching, and the University of Mexico, being church-run, was shut down. Its chapel was controversially converted into a brewery. By 1834, the anti-clerical campaign intensified, leading to the suppression of religious feasts and celebrations nationwide. Clergy were forbidden from forming confraternities without a government license. In some localities, monasteries and churches were seized, with some churches being repurposed as theaters.

4.2. Political Repression and the 'Ley del Caso'

Upon Gómez Farías' ascent to power, former ministers of Anastasio Bustamante's administration went into hiding, with the exception of Rafael Mangino y Mendívil, the former Minister of the Treasury. A tribunal was established to judge these former officials. Amidst widespread insurrections across the country, on 23 June 1833, the congress passed the controversial Ley del Caso (Law of the Case). This law authorized the arrest and six-year exile of 51 individuals deemed enemies of the government, including former President Bustamante, José Mariano Michelena, Zenon Fernandez, Francisco Molinos del Campo, José María Gutiérrez de Estrada, and Miguel Santa María. Miguel Santa María notably published a pamphlet criticizing the government for imprisoning political dissidents. It is important to note that Gómez Farías himself opposed the Ley del Caso, advocating for more moderate treatment of the opposition and opposing the death penalty for political offenses.

In addition to these political proscriptions, the government initiated a purge within the army, removing generals deemed undesirable. These measures, which had begun under Gómez Pedraza, were widely condemned as arbitrary and contributed to a growing opposition against the government within military ranks.

4.3. Internal Revolts and Conservative Backlash

The radical liberal reforms introduced by Gómez Farías swiftly provoked significant internal revolts and a strong conservative backlash across the country. On 26 May, in Morelia, Colonel Ignacio Escalada declared against the government and invited Antonio López de Santa Anna, the elected president who was then allowing Gómez Farías to govern, to join him in overthrowing the administration. Santa Anna, however, initially refused and took up arms against other insurrections. Escalada's revolt was subsequently defeated by General Valencia.

Despite Santa Anna's initial loyalty, the instability persisted. On 6 June, Santa Anna's own troops mutinied against him at Xuchi, taking him to Yautepec. They controversially proclaimed him dictator and sought to join the wider rebel movement. The rebellion then spread to the capital, and on 7 June, soldiers and police revolted, attacking the National Palace. However, this assault was ultimately repelled. Gómez Farías responded by organizing six thousand troops, placing the capital under martial law, and offering rewards for anyone who could help Santa Anna escape his mutinous troops. Santa Anna, upon realizing the failure of the capital's insurrection, escaped his rebel captors and returned to support the government. On 10 July, Santa Anna led a force of 2,400 men and six pieces of artillery out of the capital. He successfully drove the rebel General Mariano Arista, who had initially invited Santa Anna to join the rebels, into Guanajuato, where Arista surrendered on 8 October. This temporarily pacified the country.

4.4. Overthrow by Santa Anna

Despite having previously resisted multiple invitations to overthrow Gómez Farías, Antonio López de Santa Anna eventually decided to act in April 1834. This decision came amidst an intensifying backlash against the anti-clerical campaign, as Santa Anna's estate at Manga del Clavo was inundated with pleas from across the nation to restrain Gómez Farías and the liberal Congress. Compounding the pressure was ongoing infighting among Gómez Farías' own progressive supporters.

Santa Anna's intervention marked the swift end of Gómez Farías' first presidency. The Congress, which had been the architect of the radical reforms, was dissolved. The controversial patronato decree, which had granted the government power over church appointments, was annulled. Bishops who had gone into hiding were restored to their sees, signaling a reversal of the anti-clerical policies. The special tribunal established to judge former members of the Bustamante administration, which Gómez Farías himself had opposed, was abolished. The University of Mexico was reopened and restored to its former status, and those who had been exiled under the Ley del Caso were permitted to return home. This effectively dismantled the core components of Gómez Farías' liberal agenda and restored the conservative order.

5. Period Between Presidencies

Following his first overthrow, Valentín Gómez Farías faced a period of exile and political suppression, but he remained a committed advocate for federalism and liberal principles, eventually re-engaging in Mexican politics.

5.1. Exile and Return

After his deposition in April 1834, Gómez Farías left Mexico and relocated to New Orleans, where he lived off his personal savings. He eventually returned to Mexico in 1838, where he was greeted by his supporters in Veracruz. Upon his entry into the capital, some members of the public enthusiastically cheered their former president. Although Gómez Farías was legally permitted to be in the country, the council of ministers, upon learning of the fervor of his reception, passed a resolution to place him under surveillance.

Despite the government's caution, Gómez Farías managed to meet with then-President Anastasio Bustamante, whom he had helped overthrow in 1832. During this meeting, Gómez Farías assured Bustamante of his respect for the government. Nevertheless, he was subsequently arrested on suspicion of sedition. Before the judge, Gómez Farías admitted to holding political meetings at his home. However, he was released shortly thereafter, a decision influenced by one of Bustamante's short-lived ministries, which included members sympathetic to federalism.

5.2. Federalist Revolution of 1840

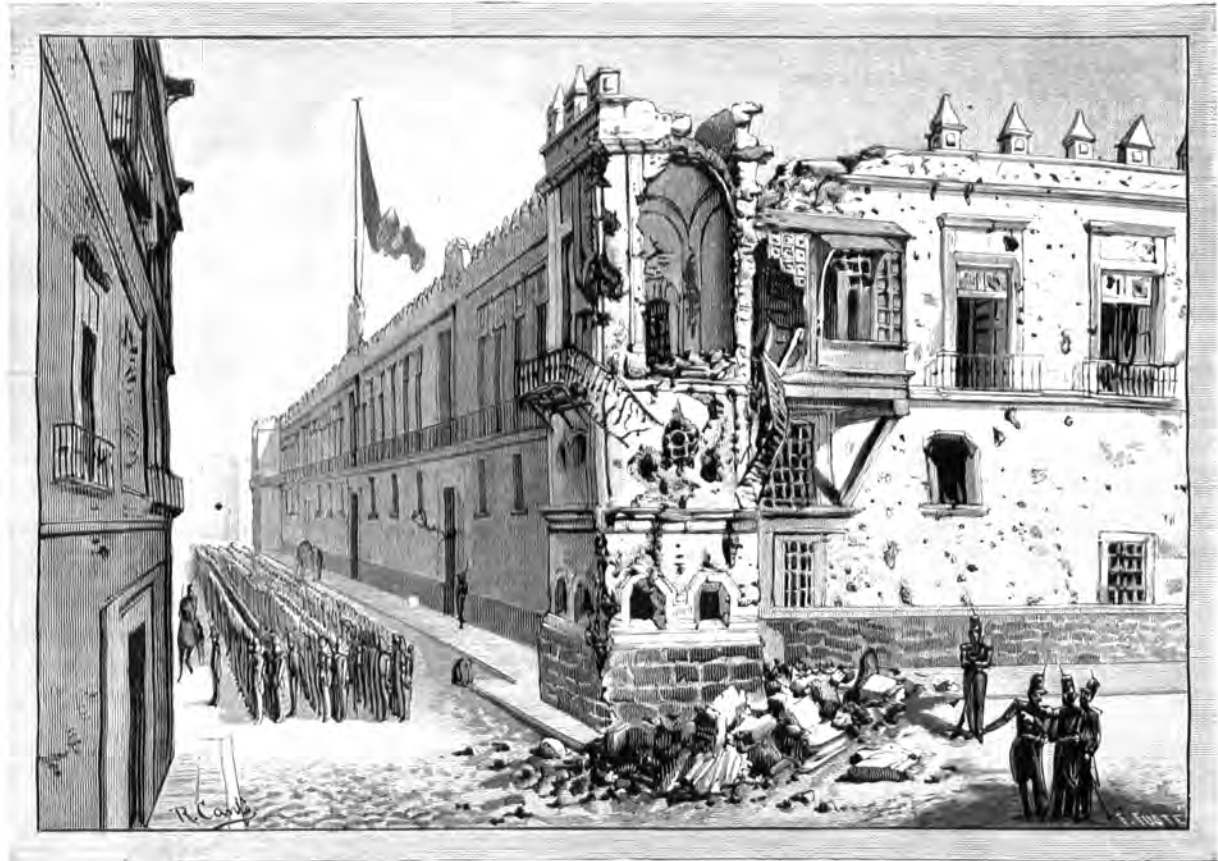

While under surveillance, Valentín Gómez Farías became involved in a conspiracy led by the Federalist General José de Urrea, who had previously attempted to overthrow President Bustamante in 1838. Urrea, despite being imprisoned, maintained communication with his federalist associates and successfully escaped from prison on 15 July 1840. With a small force of a few hundred troops, Urrea launched a daring raid on the National Palace. He managed to bypass sleeping palace guards and overpower Bustamante's private bodyguard, surprising the president in his bedchambers. As Bustamante reached for his sword, Urrea announced his presence, to which the president responded with an insult. The soldiers aimed their muskets at Bustamante but were restrained by their officer, who reminded them of Bustamante's past role as Iturbide's second-in-command. The president was assured of his personal safety but became a prisoner of the rebels. Meanwhile, Almonte, the Minister of War, managed to escape and organize a rescue effort.

The rebels then offered command of the revolution to Gómez Farías, which he accepted. Government and federalist forces converged in the capital. Federalists occupied the vicinity of the National Palace, while government forces prepared their positions for an attack. Skirmishes, sometimes involving artillery, broke out throughout the afternoon. A cannonball notably crashed through the dining room where the captive president was having dinner, scattering debris across his table.

The conflict appeared to be reaching a stalemate, prompting the release of the president in an attempt to initiate negotiations. However, these negotiations broke down, leading to twelve days of intense urban warfare in the capital. The prolonged conflict resulted in significant property damage, civilian casualties, and a large exodus of refugees from the city. News then arrived that government reinforcements, under the command of Antonio López de Santa Anna, were en route. Faced with the prospect of a protracted conflict that would devastate the capital, negotiations were resumed. An agreement was reached, establishing a ceasefire and granting amnesty to the rebels.

6. Second Presidency (1846-1847) and the Mexican-American War

Following the Federalist Revolution of 1840, Gómez Farías continued to face political turmoil and periods of exile. He went into hiding and departed for Veracruz on 2 September, then traveled to New York City, and subsequently to Yucatán, which had declared independence and advocated for a return to the federalist system. He resided there for two years before moving back to New Orleans. He finally returned to Mexico in 1845, after the overthrow of Antonio López de Santa Anna.

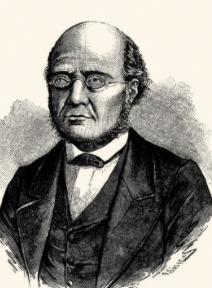

He was appointed a senator by President José Joaquín de Herrera, and Gómez Farías openly opposed Herrera's policy of seeking to end the efforts to reconquer Texas. He declined any role in the subsequent administration of Mariano Paredes, who overthrew Herrera precisely because of his conciliatory approach towards Texas. When the Mexican-American War erupted, Gómez Farías, despite their complex history, supported inviting his old political rival Santa Anna back to Mexico, believing that Santa Anna could unite the nation during such a critical crisis.

Gómez Farías briefly served as Minister of Finance under the short presidency of José Mariano Salas. He accepted the post on specific conditions: the abolition of internal tariffs, the reform of authoritarian laws, and the continuation of the war based on the unity of all Mexicans. He remained in the ministry for just over a month, a period during which Santa Anna re-entered the capital, famously accompanied in his carriage by Gómez Farías, who prominently held the Constitution of 1824 by his side, symbolizing their shared commitment to federalism.

6.1. Nationalization of Church Lands

In December 1846, Antonio López de Santa Anna and Valentín Gómez Farías were once again elected as president and vice president, respectively, mirroring their political partnership from thirteen years prior in 1833. As before, they would alternate in office, allowing Gómez Farías to serve as acting president during this critical period. Gómez Farías immediately declared that the war against the United States would be waged until all American forces were expelled from Mexican territory. However, he struggled to form a stable cabinet, and by December 1846, he faced the additional challenge of Yucatán once again seceding from Mexico and refusing to participate in the war, with Yucatecan ships even flying their own flag to avoid seizure by the American navy.

The government faced severe difficulties in financing the ongoing war, a problem exacerbated by pervasive corruption within the finance ministry, which did not inspire confidence when the government proposed an audit of property owners. On 7 January 1847, a controversial measure was introduced to Congress, signed by four of the five members of a financial ministry commission. This measure endorsed the seizure of 15.00 M MXN from the Church by nationalizing and subsequently selling its lands. This proposal immediately alarmed Gómez Farías' opponents, who feared he was reviving the anti-clerical campaign of 1833.

The decree was signed by the President of Congress, Pedro María de Anaya, and Gómez Farías approved it with the support of Finance Minister Zubieta. Zubieta was instructed to prevent any fraud or concealment of wealth that might impede the effectiveness of the measure. Tenants on church lands were to be fined if they failed to pay their rent to government agents instead of the Church. Minister of Relations José Fernando Ramírez recommended the application of relevant Indian laws in anticipation of political unrest in the churches, while Minister of War Valentin Canalizo urged the utmost severity in enforcing laws against those disrupting public order.

Local opposition to the decree was particularly strong. The legislatures of Querétaro, Puebla, and Guanajuato formally petitioned Congress to nullify the decree. The State of Durango outright refused to enforce it, and the State of Querétaro proposed an TlterNAtive plan to fund the war effort. Tenants living on church lands also resisted the decree's enforcement. The liberal newspaper El Monitor Republicano expressed incredulity that, amidst numerous options for raising funds, the government had chosen to nationalize church lands in the middle of a war without consulting public opinion, reminding its readers that a similar attempt by Gómez Farías in 1833 had led to the overthrow of the liberal government.

Minister of Relations Ramírez resigned after clashes within the cabinet, including difficulties in finding buyers for the church lands. On 26 January, President Gómez Farías appointed a junta tasked with carrying out the sales of church properties. Legal secretaries Cuevas and Mendez were fined for refusing to participate. Measures were also taken to audit the finance ministry to reduce overall corruption, and relevant officials were required to submit a report every four days detailing the progress of church land sales and explaining any delays.

Demonstrations in the capital began as early as 15 January, but the government remained obstinate in pursuing its policy of nationalizing church lands. On 21 February, the Oaxaca garrison declared against the government, followed by Mazatlán. As had occurred during Gómez Farías' first presidency, rebels began calling for Santa Anna, with whom Gómez Farías was sharing power, to take control of the government. Meanwhile, peaceful opposition to the nationalization law continued. Liberal Deputy Mariano Otero protested the measure, and the new finance minister, José Luis Huici, refused to sign it.

6.2. The Polkos Revolt and Santa Anna's Intervention

Sensing a lack of sympathy for the government among members of the newly formed national guard in the capital, Valentín Gómez Farías attempted to move them to locations where they would pose no threat. On 24 February, he dispatched troops, led by his own son, to expel the Independence Battalion from their temporary barracks near the university adjacent to the National Palace. This battalion, composed of middle-class professionals, saw their expulsion as a threat to their families' livelihoods. The action provoked widespread protest and outrage, leading to the arrest of several members of the Independence Battalion.

On 27 February, several national guard battalions openly rebelled against the government. They issued a manifesto denouncing the government for pursuing divisive policies instead of uniting the country for the war effort and seeking a nationally consensual method of funding the military. This uprising became known as the Revolt of the Polkos, a moniker derived from the young middle-class militiamen stationed throughout the capital who were known for dancing the polka. The rebels were joined by General José Mariano Salas, who had previously played a role in overthrowing President Mariano Paredes during the war. General Matías de la Peña Barragán, the rebel chief, met with Valentin Canalizo on 28 February to negotiate an agreement, with Peña insisting on the deposition of Gómez Farías. Negotiations failed, and the revolt continued.

Meanwhile, news arrived that Antonio López de Santa Anna had "won" the Battle of Buena Vista, which took place from 22 to 23 February, though it was in reality a draw. Santa Anna was returning to Mexico City to organize defenses against the forces of Winfield Scott, who had recently landed at Veracruz. While at the town of Matehuala, en route from Angostura to San Luis Potosí City, Santa Anna received news of the revolution against Valentín Gómez Farías' government.

Upon his arrival in San Luis Potosí on 10 March, Santa Anna wrote two letters: one to Gómez Farías and another to Peña Barragán, ordering both sides to suspend hostilities. They complied, awaiting Santa Anna's arrival and arbitration. On his journey to the capital, Santa Anna was met by representatives from both sides of the conflict, each hoping to sway him to their cause. On 21 March, representatives of the constitutional congress, including Mariano Otero and José María Lafragua, presented Santa Anna with an offer to assume the presidency. He continued to receive representatives from various interests and was congratulated for his "victory" at Buena Vista. Ignacio Trigueros was appointed the new governor of the federal district, and Pedro María de Anaya was named the new commandant general. These developments solidified Santa Anna's position as the arbiter of the conflict, leading to Gómez Farías' second overthrow.

7. Later Life and Constitutional Reform

Following his second presidency, Valentín Gómez Farías remained an active and influential figure in Mexican politics, notably contributing to the drafting of the Constitution of 1857, which cemented many of the liberal principles he had long championed.

7.1. Post-Presidency Political Activities

Valentín Gómez Farías resigned from the presidency, which then passed to Antonio López de Santa Anna, and the Polkos insurrection came to an end, with troops returning to their stations. Despite this, Gómez Farías remained active in politics, serving as a congressman and ardently opposing any arrangements or concessions with the Americans during the ongoing Mexican-American War.

In 1850, the newspaper El Tribuno put forth his name as a candidate for the presidency, and he also ran as the liberal candidate for the Ayuntamiento (city council) of Mexico City. He lived to witness his old colleague and rival Santa Anna re-establish a dictatorship in 1852, but also experienced Santa Anna's subsequent downfall with the triumph of the liberal Plan of Ayutla in 1855. Following the success of the Plan of Ayutla, Gómez Farías traveled to Cuernavaca to participate in the Junta of Representatives, which was installed in the city's theater on 4 October 1855. He was designated president of the Junta, with the radical Melchor Ocampo as his vice president and the future president of Mexico, Benito Juárez, as one of the secretaries. Under the presidency of Juan Álvarez, Gómez Farías was named administrator of the post office, demonstrating his continued engagement in public service.

7.2. Contribution to the Constitution of 1857

As a representative from Jalisco, Valentín Gómez Farías played a significant and integral role in the constituent congress responsible for drafting the Constitution of 1857. This was a crowning achievement for him, as the new constitution incorporated many of his long-held liberal ideals and the anti-clerical reforms he had tirelessly championed since his first presidency in 1833. His persistent advocacy ensured that principles such as the separation of church and state, secular education, and the abolition of special privileges (fueros) for the clergy and military were enshrined in the nation's fundamental law. On 5 February 1857, a testament to his enduring commitment and stature, he was the first representative to swear allegiance to the new constitution, signifying his deep personal connection to its principles.

Valentín Gómez Farías died on 5 July 1858, a few months into the Reform War, a conflict ignited by the very liberal reforms codified in the constitution he helped create. His funeral was attended by the American minister John Forsyth Jr., and he was buried in Mixcoac.

8. Assessment and Legacy

Valentín Gómez Farías holds a crucial place in Mexican history as a foundational figure of its liberal tradition. His political career, spanning a period of intense ideological conflict, laid much of the groundwork for the modern Mexican state, yet also sparked profound divisions that defined the 19th century.

8.1. Positive Contributions

Gómez Farías is widely recognized as a pioneer of liberal reforms in Mexico. He was among the earliest and most resolute proponents of a secular state, advocating for the separation of church and state at a time when the Catholic Church wielded immense political, economic, and social power. His efforts to abolish mandatory tithes, secularize education, and nationalize church properties, though met with fierce resistance, were foundational to the development of public education and a more equitable distribution of wealth. These reforms aimed to dismantle entrenched privileges, thereby promoting principles of social justice and equality before the law. His persistent support for a federal republic, even after multiple overthrows, underscored his commitment to democratic governance and the idea of a decentralized political system. His enduring influence is evident in the Constitution of 1857, which codified many of the liberal principles he had championed for decades, establishing a framework for a more modern and democratic Mexico.

8.2. Criticisms and Controversies

Despite his significant contributions, Gómez Farías' career was not without its criticisms and controversies. His radical anti-clerical measures, particularly the attempts to nationalize church lands and secularize education, were seen by conservatives as an assault on traditional values and religious freedom, fueling intense social and political backlash. The implementation of policies like the Ley del Caso, which authorized the arrest and exile of political opponents, raised concerns about political repression, even though Gómez Farías himself expressed reservations about such extreme measures.

His complex and often tumultuous relationship with Antonio López de Santa Anna remains a major point of discussion. Elected together twice, their alliance was consistently fragile, with Santa Anna repeatedly turning against Gómez Farías to placate conservative factions, leading to his overthrows. This recurring pattern highlighted Gómez Farías' difficulty in maintaining stable alliances and navigating the volatile political landscape of early independent Mexico. Critics argue that the radical nature and abrupt implementation of his reforms, especially during periods of national crisis, contributed to deep social divisions and political instability, ultimately making his administrations vulnerable to counter-revolutions.