1. Overview

Vere Gordon Childe (1892-1957) was an influential Australian archaeologist and linguist who dedicated most of his career to the study of Prehistoric Europe. Residing predominantly in the United Kingdom, he served as an academic at the University of Edinburgh and later as Director of the Institute of Archaeology in London. Childe is renowned for his pioneering contributions to Marxist archaeology in the Western world, moving beyond traditional culture-historical archaeology to interpret societal development through a materialist lens. He introduced the transformative concepts of the 'Neolithic Revolution', marking the transition to settled farming, and the 'Urban Revolution', signifying the emergence of early cities. His extensive body of work, comprising twenty-six books and numerous articles, synthesized vast archaeological data from the Near East and Europe, earning him the epithet "the Great Synthesizer."

Childe's academic pursuits were deeply intertwined with his staunch socialist and social liberal convictions. He was a vocal critic of imperialism and fascism, and his political activism often complicated his professional life, particularly in his early career in Australia. His commitment to social progress and his critical analysis of economic and social structures, shaped by his engagement with Marxism, consistently informed his archaeological interpretations, emphasizing human agency and the revolutionary impact of technological and economic advancements on society.

2. Life

Vere Gordon Childe's life was marked by intellectual brilliance, political activism, and a profound dedication to unraveling the human past. His journey spanned from a middle-class upbringing in Australia to becoming a leading figure in European archaeology, often navigating a conservative academic world while holding radical left-wing beliefs.

2.1. Childhood and Education

Vere Gordon Childe was born on April 14, 1892, in Sydney, New South Wales, Australia. He was the only surviving child of Stephen Henry Childe (1844-1923), an Anglican priest who had previously married Mary Ellen Latchford and had five children with her before her death in Australia. Stephen Childe later married Harriet Eliza Gordon (1853-1910) on November 22, 1886. Harriet, an Englishwoman from a wealthy background whose father was the Australian politician Alexander Gordon, had moved to Australia as a child. Gordon Childe grew up with his five half-siblings at his father's grand country house, the Chalet Fontenelle, in Wentworth Falls in the Blue Mountains, west of Sydney. His father, the Reverend Childe, served as a minister for St. Thomas' Parish but was often unpopular due to arguments with his congregation and unscheduled holidays.

A sickly child, Childe was initially educated at home before attending a private school in North Sydney. In 1907, he enrolled at Sydney Church of England Grammar School, where he achieved good marks in subjects including ancient history, French, Greek, Latin, geometry, algebra, and trigonometry. Despite his academic aptitude, he faced bullying due to his physical appearance and unathletic build. In July 1910, his mother passed away, and his father soon remarried. This period further strained Childe's already difficult relationship with his father, as they held opposing views on religion and politics: his father was a devout Christian and conservative, while Childe was an atheist and an emerging socialist.

In 1911, Childe commenced his studies for a degree in classics at the University of Sydney. Although his focus was primarily on written sources, he first encountered classical archaeology through the works of renowned archaeologists Heinrich Schliemann and Arthur Evans. During his university years, he became a prominent member of the debating society, notably advocating for the desirability of socialism. His interest in socialism deepened as he delved into the works of Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels, alongside the philosopher G. W. F. Hegel, whose concept of dialectics significantly influenced Marxist theory. He formed a lifelong friendship with fellow undergraduate and future judge and politician Herbert Vere Evatt. Childe concluded his studies in 1913, graduating the following year with numerous honors and prizes, including Professor Francis Anderson's prize for philosophy.

Seeking to further his education, Childe was awarded a £200 Cooper Graduate Scholarship in Classics, enabling him to attend Queen's College at the University of Oxford in England. He set sail for Britain aboard the SS Orsova in August 1914, just as World War I erupted. At Oxford, he pursued a diploma in classical archaeology and later a Literae Humaniores degree, though he never completed the diploma. He studied under influential figures such as John Beazley and Arthur Evans, the latter serving as his supervisor. In 1915, Childe published his first academic paper, "On the Date and Origin of Minyan Ware," in the Journal of Hellenic Studies. The following year, he completed his B.Litt. thesis, "The Influence of Indo-Europeans in Prehistoric Greece," which demonstrated his early interest in integrating philological and archaeological evidence. Childe later reflected on his Oxford training, noting that it adhered to a classical tradition where "bronzes, terracottas and pottery (at least if painted) were respectable while stone and bone tools were banausic."

During his time at Oxford, Childe became deeply involved with the socialist movement, often clashing with the conservative university authorities. He was a notable member of the left-wing reformist Oxford University Fabian Society, which in 1915 rebranded as the Oxford University Socialist Society after a split from the Fabian Society. His closest friend and flatmate during this period was Rajani Palme Dutt, a fervent socialist and Marxist, with whom he frequently engaged in late-night discussions and intellectual sparring over classical history. Amidst World War I, many British socialists refused military enlistment, despite government conscription, believing the war was a conflict waged by Europe's imperialist ruling classes at the expense of the working class. They argued that class war was the only struggle that mattered. Dutt was imprisoned for refusing to fight, and Childe actively campaigned for his release and that of other socialist and pacifist conscientious objectors. Childe himself was never required to enlist, likely due to his poor health and eyesight. His strong anti-war sentiments attracted the attention of authorities; MI5 opened a file on him, intercepted his mail, and kept him under surveillance.

2.2. Early Career and Political Activism

Upon his return to Australia in August 1917, Childe found himself under surveillance by security services due to his known socialist activism, with his mail routinely intercepted. His political convictions significantly impacted his career prospects.

2.2.1. In Australia

In 1918, Childe became a senior resident tutor at St Andrew's College, at the University of Sydney, and became involved with the city's socialist and anti-conscription movements. During Easter 1918, he delivered a speech at the Third Inter-State Peace Conference, an event organized by the Australian Union of Democratic Control for the Avoidance of War, which opposed Prime Minister Billy Hughes's conscription plans. The conference, heavily influenced by socialist ideals, asserted in its report that the "abolition of the Capitalist System" was the best hope for ending international conflict. News of Childe's participation reached the Principal of St Andrew's College, who, despite significant staff opposition, forced Childe to resign.

His colleagues at the university then secured him a position as a tutor in ancient history within the Department of Tutorial Classes. However, the university chancellor, William Cullen, fearing that Childe would propagate socialist ideologies among students, promptly fired him. This dismissal was widely condemned by the leftist community as a violation of Childe's civil rights, and center-left politicians William McKell and T.J. Smith even raised the issue in the Parliament of Australia. In October 1918, Childe relocated to Maryborough, Queensland, to teach Latin at the Maryborough Boys Grammar School, where one of his students was P. R. Stephensen. Again, his political affiliations became public, triggering an opposition campaign from local conservative groups and the Maryborough Chronicle, leading to abuse from some pupils. Consequently, he soon resigned from this post as well.

Recognizing that the university authorities would bar him from any academic career, Childe sought employment within the leftist movement. In August 1919, he became the private secretary and speechwriter for the politician John Storey, a prominent member of the center-left Labor Party, which was then in opposition to New South Wales' Nationalist Party government. Storey, who represented the Sydney suburb of Balmain in the New South Wales Legislative Assembly, became state premier in 1920 following Labor's electoral victory. Working within the Labor Party provided Childe with deeper insight into its operations, but the more involved he became, the more critical he grew of the party. He came to believe that once in political office, Labor politicians abandoned their socialist ideals, shifting towards a centrist, pro-capitalist stance. He secretly joined the radical leftist Industrial Workers of the World, which was banned in Australia at the time. In 1921, Storey dispatched Childe to London to keep the British press informed about developments in New South Wales. However, Storey's sudden death in December, followed by an election that restored a Nationalist government under George Fuller's premiership, led Fuller to deem Childe's position unnecessary, terminating his employment in early 1922.

2.2.2. Settling in London and Early Publications

Unable to secure an academic position in Australia, Childe opted to remain in Britain. He rented a room in Bloomsbury, Central London, and dedicated much of his time to studying at the British Museum and the Royal Anthropological Institute library. He actively participated in London's socialist movement, frequenting the 1917 Club in Gerrard Street, Soho, where he befriended members of the Marxist Communist Party of Great Britain (CPGB) and contributed articles to their publication, Labour Monthly. Despite these affiliations, he had not yet openly declared himself a Marxist.

By this time, Childe had earned a solid reputation as a prehistorian, leading to invitations to study prehistoric artifacts across Europe. In 1922, he traveled to Vienna to examine previously unpublished Neolithic painted pottery from Schipenitz, Bukovina, housed in the Prehistoric Department of the Natural History Museum. He published his findings in the 1923 volume of the Journal of the Royal Anthropological Institute. This excursion also allowed him to visit museums in Czechoslovakia and Hungary, which he subsequently brought to the attention of British archaeologists in a 1922 article in Man. After returning to London, in 1922, Childe worked as a private secretary for three Members of Parliament, including John Hope Simpson and Frank Gray, both members of the center-left Liberal Party. To supplement his income, he also translated for the publishers Kegan Paul, Trench, Trübner & Co. and occasionally lectured on prehistory at the London School of Economics.

In 1923, the London Labour Company published his first book, How Labour Governs, which critically examined the Australian Labor Party and its ties to the Australian labour movement. The book reflected Childe's growing disillusionment with the party, arguing that once elected, its politicians abandoned their socialist ideals in pursuit of personal comfort. In How Labour Governs, Childe expressed his disillusionment with the Australian Labor Party, lamenting that "As the [Australian] Labour Party, starting with a band of inspired Socialists, degenerated into a vast machine for capturing political power, but did not know how to use that political power except for the profit of individuals; so the [One Big Union] will, in all likelihood, become just a gigantic apparatus for the glorification of a few bosses. Such is the history of all Labour organizations in Australia, and that is not because they are Australian, but because they are Labour." Childe's biographer, Sally Green, highlighted the particular significance of How Labour Governs at the time of its publication, as the British Labour Party was emerging as a major force in British politics, challenging the traditional two-party dominance of the Conservatives and Liberals; in 1923, Labour formed their first government. Childe had plans for a sequel to further elaborate on his ideas, but it was never published.

In May 1923, he visited museums in Lausanne, Bern, and Zürich to study their prehistoric artifact collections. That same year, he became a member of the Royal Anthropological Institute, and in 1925, he was appointed its librarian. This position, one of the few archaeological jobs available in Britain at the time, allowed him to solidify connections with scholars throughout Europe. His role made him well-known within Britain's small archaeological community, and he developed a close friendship with O. G. S. Crawford, the archaeological officer to the Ordnance Survey, influencing Crawford's shift towards socialism and Marxism.

In 1925, Kegan Paul, Trench, Trübner & Co. published Childe's second book, The Dawn of European Civilisation. In this seminal work, he synthesized years of data on European prehistory. The book was particularly important because it appeared at a time when there were few professional archaeologists across Europe and most museums focused solely on their local areas; The Dawn was a rare example of a broader continental perspective. Its significance also lay in its introduction of the concept of the archaeological culture from continental scholarship into Britain, a move that greatly aided the development of culture-historical archaeology. Childe later articulated that the book "aimed at distilling from archaeological remains a preliterate substitute for the conventional politico-military history with cultures, instead of statesmen, as actors, and migrations in place of battles." In 1926, he released a successor, The Aryans: A Study of Indo-European Origins, which explored the theory that civilization diffused northward and westward into Europe from the Near East via an Indo-European linguistic group known as the Aryans. Following the subsequent racial appropriation of the term "Aryan" by the German Nazi Party, Childe deliberately avoided any mention of this book. In What Happened in History (1942), Childe critically addressed the Nazi misuse of the term "Aryan", stating: "Because the early Hindus and Persians did really call themselves Aryans, this term was adopted by some nineteenth-century philologists to designate the speakers of the 'parent tongue'. It is now applied scientifically only to the Hindus, Iranian peoples and the rulers of Mitanni whose linguistic ancestors spoke closely related dialects and even worshipped common deities. As used by Nazis and anti-semites generally, the term 'Aryan' means as little as the words 'Bolshie' and 'Red' in the mouths of crusted Tories." In these early works, Childe embraced a moderate form of diffusionism, proposing that while most cultural developments spread from one place to another, it was also possible for the same traits to emerge independently in different regions, contrasting with the hyper-diffusionism advocated by Grafton Elliot Smith.

2.3. Abercromby Professorship at Edinburgh University

In 1927, the University of Edinburgh offered Childe the newly established position of Abercromby Professor of Archaeology, endowed by the bequest of prehistorian Lord Abercromby. Though he was saddened to leave London, Childe accepted the offer and relocated to Edinburgh in September 1927. At 35, he became the "only academic prehistorian in a teaching post in Scotland." Many Scottish archaeologists initially regarded him as an outsider with no specific expertise in Scottish prehistory, creating an atmosphere Childe described to a friend as "hatred and envy." Despite this, he forged friendships in Edinburgh with archaeologists like W. Lindsay Scott, Alexander Curle, J. G. Callender, and Walter Grant, as well as non-archaeologists such as the physicist Charles Galton Darwin, whose youngest son Childe became godfather to. Initially, Childe resided in Liberton before moving to the semi-residential Hotel de Vere on Eglinton Crescent.

At Edinburgh University, Childe prioritized research over teaching. He was noted for his kindness toward students, though he struggled with delivering lectures to large audiences. Many students found his BSc degree course in archaeology confusing due to its counter-chronological structure, which began with the more recent Iron Age before working backward to the Palaeolithic. To foster engagement, he founded the Edinburgh League of Prehistorians, taking his more enthusiastic students on excavations and inviting guest lecturers. An early proponent of experimental archaeology, Childe involved his students in his experiments, notably investigating the vitrification process observed at several Iron Age forts in northern Britain in 1937.

Childe frequently traveled to London to visit friends, including Stuart Piggott, another influential British archaeologist who later succeeded him as Edinburgh's Abercromby Professor. He also befriended and encouraged Grahame Clark in his research. This trio were elected to the committee of the Prehistoric Society of East Anglia. At Clark's suggestion, in 1935, they used their influence to transform it into a nationwide organization, the Prehistoric Society, with Childe elected as its first president. The society experienced rapid growth, with membership increasing from 353 in 1935 to 668 by 1938.

Fluent in several European languages, which he had taught himself in his early travels across the continent, Childe spent considerable time in continental Europe attending conferences. In 1935, he made his first visit to the Soviet Union, spending 12 days in Leningrad and Moscow. Deeply impressed by the socialist state, he was particularly interested in the social role of Soviet archaeology. Upon his return to Britain, he became a vocal Soviet sympathizer and avidly read the CPGB's Daily Worker, though he remained critical of certain Soviet policies, notably the Molotov-Ribbentrop Pact with Nazi Germany.

His unwavering socialist convictions led to an early and strong denunciation of European fascism. Childe was outraged by the Nazi co-option of prehistoric archaeology to glorify their concept of an "Aryan racial heritage." He supported the British government's decision to fight the fascist powers in the Second World War, going so far as to believe he was on a Nazi blacklist and resolved to drown himself in a canal should the Nazis conquer Britain. While opposing fascist Germany and Italy, he also criticized the imperialist, capitalist governments of the United Kingdom and the United States, repeatedly describing the latter as being filled with "loathsome fascist hyenas." Despite these strong views, he visited the U.S. in 1936 to address a Conference of Arts and Sciences commemorating the tercentenary of Harvard University, where he was awarded an honorary Doctor of Letters degree. He returned in 1939, delivering lectures at Harvard, the University of California, Berkeley, and the University of Pennsylvania.

2.3.1. Major Excavations

Childe's university position at Edinburgh necessitated that he undertake archaeological excavations, a task he reportedly loathed and believed he performed poorly. While students agreed with his self-assessment regarding fieldwork technique, they nonetheless recognized his "genius for interpreting evidence." Unlike many of his contemporaries, Childe was meticulous in writing up and publishing his findings, producing almost annual reports for the Proceedings of the Society of Antiquaries of Scotland. He was also notably diligent in acknowledging the contributions of every digger, a practice uncommon at the time.

His most renowned excavation took place from 1928 to 1930 at Skara Brae in the Orkney Islands. This project uncovered a remarkably well-preserved Neolithic village, and Childe published the excavation results in his 1931 book, Skara Brae. Although he made an interpretive error by erroneously attributing the site to the Iron Age, the work itself was significant. During this excavation, Childe developed a strong rapport with the local community, who perceived him as "every inch the professor" due to his eccentric appearance and habits. In 1932, collaborating with the anthropologist C. Daryll Forde, Childe excavated two Iron Age hillforts at Earn's Hugh on the Berwickshire coast. In June 1935, he led an excavation at a promontory fort at Larriban, near Knocksoghey in Northern Ireland. Alongside Wallace Thorneycroft, a fellow of the Society of Antiquaries of Scotland, Childe excavated two vitrified Iron Age forts in Scotland: one at Finavon, Angus (1933-34), and another at Rahoy, Argyllshire (1936-37). In 1938, he and Walter Grant oversaw excavations at the Neolithic settlement of Rinyo; their work paused during the Second World War but resumed in 1946.

2.3.2. Major Publications

Throughout his professorship at Edinburgh, Childe continued his prolific writing and publication of archaeological books, building upon his earlier works. He initiated a series that compiled and synthesized archaeological data from across Europe. The first in this series was The Most Ancient Near East (1928), which brought together information from Mesopotamia and India, providing a crucial backdrop for understanding the spread of farming and other technologies into Europe. This was followed by The Danube in Prehistory (1929), a work that examined the archaeology along the Danube river, which Childe recognized as a natural boundary separating the Near East from Europe. He believed the Danube served as a primary conduit for the westward movement of new technologies. Although Childe had utilized culture-historical approaches in his previous publications, The Danube in Prehistory marked his first explicit definition of the concept of an archaeological culture, a contribution that revolutionized the theoretical approach of British archaeology. In this book, he famously articulated: "We find certain types of remains-pots, implements, ornaments, burial rites, house forms-constantly recurring together. Such a complex of regularly associated traits we shall term a 'cultural group' or just a 'culture'. We assume that such a complex is the material expression of what today would be called a people."

Childe's subsequent book, The Bronze Age (1930), focused on the Bronze Age in Europe and clearly demonstrated his increasing adoption of Marxist theory as a framework for understanding societal function and change. He posited that metal was the first indispensable article of commerce, making metal-smiths full-time professionals who subsisted on the social surplus. In 1933, Childe traveled to Asia, visiting Iraq-a place he found "great fun"-and India, which he described as "detestable" due to the intense heat and extreme poverty. After touring archaeological sites in both countries, he concluded that much of his earlier work in The Most Ancient Near East was outdated. This led him to produce New Light on the Most Ancient Near East (1935), in which he applied his Marxist-influenced ideas about the economy to his conclusions.

Following the publication of Prehistory of Scotland (1935), Childe produced one of the most defining books of his career, Man Makes Himself (1936). Heavily influenced by Marxist views of history, Childe argued against the traditional distinction between (pre-literate) prehistory and (literate) history, asserting it was a false dichotomy. Instead, he proposed that human society had progressed through a series of revolutionary technological, economic, and social transformations. These included the Neolithic Revolution, a period when hunter-gatherers began settling into permanent farming communities, leading to the Urban Revolution, which saw the development from small towns to the first cities, and extending up to more recent times with the Industrial Revolution altering the nature of production.

With the outbreak of the Second World War, Childe's ability to travel across Europe was curtailed, leading him to focus on writing Prehistoric Communities of the British Isles (1940). His pessimism regarding the war's outcome led him to believe that "European civilization-capitalist and Stalinist alike-was irrevocably headed for a Dark Age." In this mindset, he produced a sequel to Man Makes Himself titled What Happened in History (1942), offering an account of human history from the Palaeolithic period through to the fall of the Roman Empire. Although Oxford University Press offered to publish the work, Childe chose to release it through Penguin Books because they could sell it at a cheaper price, a decision he considered crucial for disseminating knowledge to "the masses." This was followed by two shorter works, Progress and Archaeology (1944) and The Story of Tools (1944), the latter being an explicitly Marxist text written for the Young Communist League.

2.4. Director of the Institute of Archaeology, London

In 1946, Childe departed from Edinburgh to assume the prestigious position of Director and Professor of European Prehistory at the Institute of Archaeology (IOA) in London. Eager to return to the capital, he deliberately refrained from expressing his disapproval of government policies to ensure he would not be prevented from securing the job. He took up residence in the Isokon building near Hampstead.

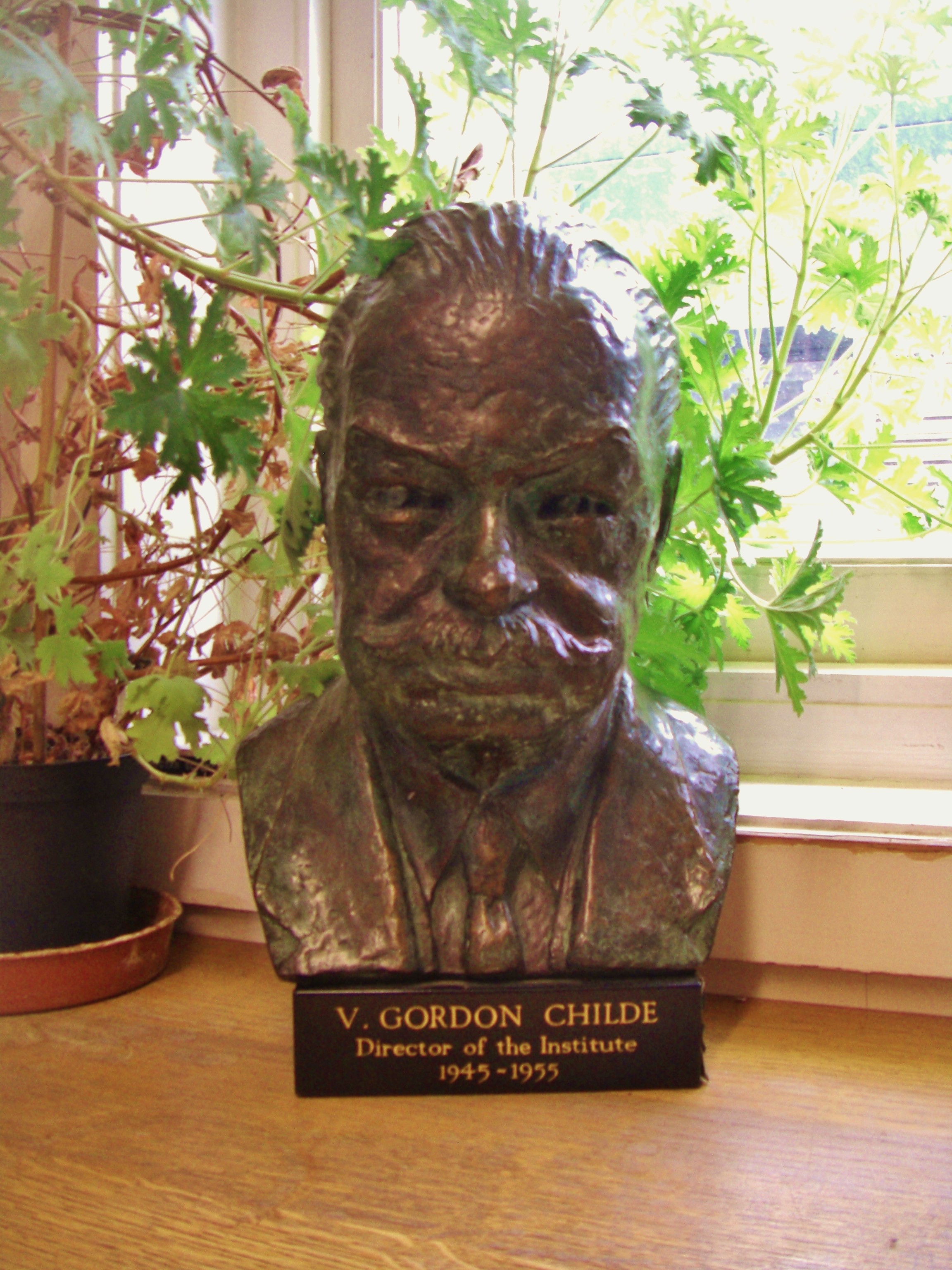

The IOA, located in St John's Lodge within the Inner Circle of Regent's Park, had been founded in 1937, largely through the efforts of archaeologist Mortimer Wheeler. However, until Childe's arrival in 1946, it had primarily relied on volunteer lecturers. Childe's relationship with the conservative Wheeler was often strained, owing to their vastly different personalities; Wheeler was an extrovert who sought public attention, an efficient administrator, and intolerant of others' shortcomings, whereas Childe lacked administrative skills and was generally more tolerant. Despite his administrative deficiencies, Childe was popular among the institute's students, who saw him as a kindly eccentric. They collectively commissioned a bronze bust of Childe by Marjorie Maitland Howard, which has been kept in the Institute of Archaeology library since 1958, although Childe himself thought it made him resemble a Neanderthal. His lecturing style was generally considered poor, as he often mumbled and would walk into an adjacent room while continuing to speak, further confusing his audience by referring to the socialist states of Eastern Europe by their full official titles and using their Slavonic names rather than their more commonly known English names. Nevertheless, he was regarded as more effective in giving tutorials and seminars, where he dedicated more time to interacting with his students. As Director, Childe was not obligated to undertake excavations, but he did oversee projects at the Orkney Neolithic burial tombs of Quoyness (1951) and Maeshowe (1954-55).

In 1949, Childe, along with O. G. S. Crawford, resigned as fellows of the Society of Antiquaries. Their resignation was a protest against the selection of James Mann, the keeper of the Tower of London's armouries, as the society's president, as they believed Wheeler, a professional archaeologist, was a more suitable choice. Childe joined the editorial board of the periodical Past & Present, which was founded by Marxist historians in 1952. During the early 1950s, he also served as a board member for The Modern Quarterly-later renamed The Marxist Quarterly-working alongside its chairman, Rajani Palme Dutt, his lifelong friend and former flatmate from his Oxford days. Childe authored occasional articles for Palme Dutt's socialist journal, the Labour Monthly, but they disagreed vehemently over the Hungarian Revolution of 1956; Palme Dutt defended the Soviet Union's military intervention to crush the revolution, while Childe, like many Western socialists, strongly opposed it. This event led Childe to abandon his faith in the Soviet leadership, though not in socialism or Marxism itself. He maintained a deep affection for the Soviet Union, having visited on multiple occasions (1935, 1945, 1953, and 1956). He was also involved with a CPGB satellite body, the Society for Cultural Relations with the USSR, and served as president of its National History and Archaeology Section from the early 1950s until his death.

Despite his prominent academic standing, Childe faced political restrictions during the Cold War era. He received multiple invitations to lecture in the United States from scholars like Robert Braidwood, William Duncan Strong, and Leslie White, but the U.S. State Department consistently barred him from entering the country due to his Marxist beliefs. While working at the institute, Childe continued his prolific writing. His book History (1947) promoted a Marxist perspective on the past and reaffirmed his conviction that prehistory and literate history should be studied together. Prehistoric Migrations (1950) showcased his views on moderate diffusionism. In 1946, he published "Archaeology and Anthropology" in the Southwestern Journal of Anthropology, arguing for the integrated use of archaeology and anthropology-an approach that would gain widespread acceptance after his death. In April 1956, Childe was honored with the Gold Medal of the Society of Antiquaries for his outstanding contributions to archaeology.

2.5. Retirement and Death

In mid-1956, Vere Gordon Childe retired as IOA director a year earlier than planned. The field of European archaeology had expanded rapidly during the 1950s, leading to increasing specialization and making the broad syntheses for which Childe was renowned increasingly difficult. Furthermore, the institute was in the process of relocating to Gordon Square, Bloomsbury, and Childe wished to provide his successor, W.F. Grimes, a fresh start in the new surroundings. To commemorate his achievements, the Proceedings of the Prehistoric Society published a Festschrift edition on the final day of his directorship, featuring contributions from friends and colleagues worldwide, an gesture that deeply moved Childe.

Upon his retirement, Childe privately informed many friends of his intention to return to Australia, visit relatives, and then commit suicide. He harbored a profound fear of aging, becoming senile, and burdening society, and also suspected he had cancer. Some later commentators suggested that a core reason for his suicidal thoughts was a loss of faith in Marxism following the Hungarian Revolution of 1956 and Nikita Khrushchev's denouncement of Joseph Stalin. However, Bruce Trigger, a prominent Childe biographer, dismissed this explanation, noting that while Childe was critical of Soviet foreign policy, he never equated the Soviet state with Marxism itself.

Childe meticulously sorted out his affairs, donating the majority of his extensive library and his entire estate to the Institute of Archaeology. After a holiday in February 1957, visiting archaeological sites in Gibraltar and Spain, he sailed to Australia, arriving in Sydney on his 65th birthday. There, the University of Sydney, which had once barred him from employment due to his political views, awarded him an honorary degree. He spent six months traveling around Australia, visiting family members and old friends, but he was largely unimpressed by Australian society, which he perceived as reactionary, increasingly suburban, and poorly educated. He did, however, find Australian prehistory a promising field for research. He lectured to various archaeological and leftist groups on this and other topics, and notably used Australian radio to criticize academic racism towards Indigenous Australians.

Childe wrote personal letters to many friends, including one to W.F. Grimes, instructing that it not be opened until 1968. In this letter, he detailed his fear of old age and stated his clear intention to take his own life, remarking that "life ends best when one is happy and strong." On October 19, 1957, Childe visited the area of Govett's Leap in Blackheath, a part of the Blue Mountains where he had grown up. He left his hat, spectacles, compass, pipe, and Mackintosh raincoat on the cliffs, then fell approximately 1.00 K ft to his death. A coroner initially ruled his death accidental, but it was definitively recognized as suicide after his letter to Grimes was published in the 1980s. His remains were cremated at the Northern Suburbs Crematorium, and his name was added to a small family plaque in the Crematorium Gardens. Following his death, the archaeological community issued an "unprecedented" level of tributes and memorials, all, according to archaeologist Ruth Tringham, testifying to his status as Europe's "greatest prehistorian and a wonderful human being."

3. Archaeological Theory and Ideas

Vere Gordon Childe's contributions to archaeological theory were profound and constantly evolving, marked by a unique synthesis of diverse intellectual currents and a consistent challenge to prevailing orthodoxies.

3.1. Overview of Theoretical Approach

Biographer Sally Green observed that Childe's beliefs were "never dogmatic, always idiosyncratic" and "continually changing throughout his life." His theoretical approach ingeniously blended elements of Marxism, diffusionism, and functionalism. Childe was a critical voice against the evolutionary archaeology that dominated the nineteenth century, arguing that its adherents placed undue emphasis on artifacts rather than on the human societies that created them. Like most archaeologists in Western Europe and the United States during his working decades, Childe did not view humans as inherently inventive or naturally inclined to change. Consequently, he tended to interpret social change primarily in terms of diffusion and migration, rather than through internal development or cultural evolution. According to biographer Bruce Trigger, the most important source of Childe's thinking was the highly developed Western European archaeology, but his research was also influenced by Soviet archaeology, American anthropology, and his subsidiary interest in philosophy and politics. Trigger noted that Childe was more concerned than most of his contemporaries with justifying the social value of archaeology.

Childe worked during a period when most archaeologists adhered to the three-age system, first developed by the Danish antiquarian Christian Jürgensen Thomsen. This system posited an evolutionary chronology dividing prehistory into the Stone Age, Bronze Age, and Iron Age. While acknowledging its utility, Childe critically noted that many contemporary societies globally still operated with effectively Stone Age technology. Nevertheless, he recognized the three-age system as a valuable model for analyzing socio-economic development when integrated with a Marxist framework. He used technological criteria for the main divisions of prehistory but applied economic criteria to subdivide the Stone Age into the Palaeolithic and Neolithic periods, rejecting the concept of the Mesolithic as unnecessary. Informally, he also adopted the framework of "savagery," "barbarism," and "civilization" for past societies, as employed by Engels.

3.2. Culture-Historical Archaeology

In the early phase of his career, Childe was a prominent advocate of the culture-historical approach to archaeology, ultimately being recognized as one of its "founders and chief exponents." This school of thought centered on the concept of "culture," a term adopted from anthropology, which marked "a major turning point in the history of the discipline" by enabling archaeologists to analyze the past through a spatial rather than merely temporal dynamic. Childe adopted the concept of "culture" from the German philologist and archaeologist Gustaf Kossinna, though this influence may have been mediated through Leon Kozłowski, a Polish archaeologist who had adopted Kossinna's ideas and maintained a close association with Childe. However, historian Bruce Trigger noted that while Childe embraced Kossinna's fundamental concept, he displayed "no awareness" of the "racist connotations" Kossinna had imbued it with.

Childe's commitment to the culture-historical model is evident in his early works, including The Dawn of European Civilisation (1925), The Aryans (1926), and The Most Ancient East (1928), though none of these provided a formal definition of "culture." It was only later, in The Danube in Prehistory (1929), that Childe offered a specifically archaeological definition of "culture." In this landmark publication, he defined a "culture" as a consistent set of "regularly associated traits" within the material culture-such as "pots, implements, ornaments, burial rites, house forms"-that recurrently appear across a given geographical area. He asserted that, in this context, an "archaeological culture" served as the material expression of what today would be called a "people." Childe's use of the term "people" was explicitly non-racial; he viewed it as a social grouping rather than a biological race. He adamantly opposed the erroneous equation of archaeological cultures with biological races-a practice increasingly common among various nationalist movements across Europe at the time-and vociferously criticized Nazi misuses of archaeology, arguing that the Jewish people were a socio-cultural grouping, not a distinct biological race. In 1935, influenced by anthropological functionalism, Childe suggested that culture functioned as a "living functioning organism" and emphasized the adaptive potential of material culture. He also acknowledged that archaeologists defined "cultures" based on a subjective selection of material criteria, a perspective that was later widely adopted by other archaeologists, notably Colin Renfrew.

Towards the later stages of his career, Childe grew weary of culture-historical archaeology. By the late 1940s, he began to question the practical utility of "culture" as an archaeological concept and, by extension, the fundamental validity of the culture-historical approach itself. Barbara McNairn suggested this shift was partly due to the term "culture" becoming broadly adopted across the social sciences to refer to all learned modes of behavior, moving beyond Childe's more specific focus on material culture. By the 1940s, Childe harbored doubts as to whether a particular archaeological assemblage or "culture" truly reflected a social group with other unifying traits, such as a shared language. In the 1950s, he critically compared the role of culture-historical archaeology among prehistorians to the place of the traditional politico-military approach among historians, implying its limitations in fully explaining the complexities of human history.

3.3. Marxist Archaeology

Childe is widely regarded as a pivotal figure in Marxist archaeology, being the first archaeologist in the Western world to systematically apply Marxist theory in his work. Marxist archaeology itself emerged in the Soviet Union in 1929, with the publication of Vladislav I. Ravdonikas's report, "For a Soviet History of Material Culture." Ravdonikas criticized the conventional archaeological discipline as inherently bourgeois and anti-socialist, advocating for a pro-socialist, Marxist approach to archaeology as part of the academic reforms implemented under Joseph Stalin's rule. It was during the mid-1930s, around the time of his initial visit to the Soviet Union, that Childe began to explicitly reference Marxism in his own archaeological works.

Many archaeologists have been profoundly influenced by Marxism's socio-political ideas. As a materialist philosophy, Marxism emphasizes that material conditions are foundational, asserting that the social conditions of a given period stem from the existing material conditions, or mode of production. Thus, a Marxist interpretation prioritizes the social context of any technological development or change. Marxist thought also highlights the inherently biased nature of scholarship, arguing that each scholar's work is shaped by their entrenched beliefs and class loyalties, and that intellectuals cannot divorce their scholarly thinking from political action. Sally Green noted that Childe adopted "Marxist views on a model of the past" because they offered "a structural analysis of culture in terms of economy, sociology and ideology, and a principle for cultural change through economy." Barbara McNairn described Marxism as "a major intellectual force in Childe's thought," while Bruce Trigger stated that Childe identified with Marx's theories "both emotionally and intellectually."

Childe himself stated that he utilized Marxist ideas in interpreting the past "because and in so far as it ''works'','' often criticizing fellow Marxists for treating the socio-political theory as a set of dogmas: "To the average communist and anti-communist alike-... Marxism means a set of dogmas-the words of the master from which as among mediaeval schoolmen, one must deduce truths which the scientist hopes to infer from experiment and observation." His interpretation of Marxism frequently diverged from the orthodoxies of his contemporaries, partly because he referred directly to the original texts of Hegel, Marx, and Engels rather than later interpretations, and partly due to his selective application of their writings. McNairn characterized Childe's Marxism as "an individual interpretation" distinct from "popular or orthodox" Marxism. Trigger lauded him as a "creative Marxist thinker," while Peter Gathercole observed that while Childe's "debt to Marx was quite evident," his "attitude to Marxism was at times ambivalent." The Marxist historian Eric Hobsbawm later referred to Childe as "the most original English Marxist writer from the days of my youth." Childe was keenly aware that his association with Marxism could be precarious during the Cold War and consequently sought to make his Marxist ideas more palatable to his readership, sparingly making direct references to Marx in his archaeological publications. A distinction can be drawn in his later works between those that were explicitly Marxist and those where Marxist ideas and influences were less overt. Many of Childe's fellow British archaeologists did not take his adherence to Marxism seriously, often viewing it as something he adopted for shock value.

Childe's understanding of historical processes was rooted in a materialist framework, as he articulated: "The Marxist view of history and prehistory is admittedly material determinist and materialist. But its determinism does not mean mechanism. The Marxist account is in fact termed 'dialectical materialism'. It is deterministic in as much as it assumes that the historical process is not a mere succession of inexplicable or miraculous happenings, but that all the constituent events are interrelated and form an intelligible pattern."

While influenced by Soviet archaeology, Childe remained critical of its dogmatism. He disapproved of the Soviet government's encouragement for archaeologists to presume their conclusions before adequately analyzing their data. He also criticized what he perceived as a sloppy approach to typology in Soviet archaeology. As a moderate diffusionist, Childe was particularly critical of the "Marrist" trend in Soviet archaeology, based on the theories of the Georgian philologist Nicholas Marr, which rejected diffusionism in favor of unilinear evolutionism. In Childe's view, it "cannot be un-Marxian" to understand the spread of domesticated plants, animals, and ideas through diffusion. He chose not to publicly air these criticisms of his Soviet colleagues, possibly to avoid offending communist friends or providing ammunition for right-wing archaeologists. Instead, he publicly praised the Soviet system of archaeology and heritage management, favorably contrasting it with Britain's for its emphasis on collaboration over competition among archaeologists. Despite his enduring affection for the Soviet Union, which he visited multiple times (1935, 1945, 1953, 1956) and where he befriended many Soviet archaeologists, he sent a letter to the Soviet archaeological community shortly before his suicide, expressing "extreme disappointment" that they had methodologically fallen behind Western Europe and North America.

Other Marxists, such as George Derwent Thomson and Neil Faulkner, argued that Childe's archaeological work was not entirely Marxist because he failed to sufficiently account for class struggle as a primary instrument of social change, a core tenet of Marxist thought. While class struggle was not a factor Childe heavily emphasized in his archaeological interpretations, he did acknowledge that historians and archaeologists typically interpreted the past through their own class interests, asserting that most of his contemporaries produced studies with an inherent bourgeois agenda. Childe further diverged from orthodox Marxism by not explicitly employing dialectics in his methodology. Moreover, he denied Marxism's ability to predict the future development of human society, and-unlike many other Marxists-he did not consider humanity's progress towards pure communism as inevitable, instead opining that society could stagnate or even face extinction.

3.4. Neolithic and Urban Revolutions

Influenced by Marxist thought, Childe argued that society experienced widespread and profound changes over relatively short periods, citing the Industrial Revolution as a modern example. This concept of rapid, transformative change was absent from his earliest work, where he described societal shifts as "transition" rather than "revolution," as seen in studies like The Dawn of European Civilisation. However, in his writings from the early 1930s, such as New Light on the Most Ancient East, he began to employ the term "revolution" to describe social change, a term that had gained significant Marxist associations following Russia's October Revolution of 1917.

Childe formally introduced his ideas about "revolutions" in a 1935 presidential address to the Prehistoric Society. Presenting this concept as part of his functional-economic interpretation of the three-age system, he posited that a "Neolithic Revolution" initiated the Neolithic era, and that other revolutions marked the beginning of the Bronze and Iron Ages. The following year, in Man Makes Himself, he combined these Bronze and Iron Age Revolutions into a singular "Urban Revolution", a concept that largely corresponded to the anthropologist Lewis H. Morgan's framework of "civilization."

For Childe, the Neolithic Revolution represented a period of radical transformation during which humans, previously hunter-gatherers, began cultivating plants and breeding animals for food. This shift allowed for unprecedented control over the food supply and facilitated significant population growth. He believed the Urban Revolution was largely propelled by the development of bronze metallurgy. In a seminal 1950 paper, Childe proposed ten key traits that he believed characterized the earliest cities: they were considerably larger than earlier settlements; they contained full-time craft specialists; the agricultural surplus was collected and centralized, often given to a god or king; they featured monumental architecture; there was an unequal distribution of social surplus; writing was invented; the sciences developed; naturalistic art emerged; trade with foreign areas increased; and state organization was based on residence rather than kinship. However, Childe also highlighted a negative aspect of the Urban Revolution: it led to increased social stratification into classes and the oppression of the majority by a power elite. Not all archaeologists adopted Childe's framework of understanding human societal development as a series of transformational "revolutions"; many argued that the term "revolution" was misleading because the processes of agricultural and urban development were, in reality, gradual transformations over extended periods.

3.5. Influence on Later Archaeology

Through his extensive body of work, Childe significantly influenced two major theoretical movements in Anglo-American archaeology that emerged in the decades following his death: processualism and post-processualism. Processualism, which developed in the late 1950s, emphasized the notion that archaeology should function as a branch of anthropology, aiming to discover universal laws about society and believing that archaeology could ascertain objective information about the past. Post-processualism, emerging as a reaction to processualism in the late 1970s, rejected the idea of objective archaeological information, instead stressing the inherent subjectivity of all interpretation.

The prominent processual archaeologist Colin Renfrew, a leading figure in the field, described Childe as "one of the fathers of processual thought" due to his "development of economic and social themes in prehistory," a sentiment echoed by Neil Faulkner. Bruce Trigger further argued that Childe's work foreshadowed processual thought in two key ways: by emphasizing the crucial role of change in societal development and by adhering to a strictly materialist view of the past, both of which stemmed directly from Childe's Marxist leanings. Despite this connection, most American processualists largely overlooked Childe's work, mistakenly perceiving him as a particularist whose ideas were irrelevant to their pursuit of generalized laws of societal behavior. In line with Marxist thought, Childe did not agree that such generalized laws exist, believing instead that human behavior is not universal but fundamentally conditioned by socio-economic factors.

Peter Ucko, one of Childe's successors as director of the Institute of Archaeology, highlighted that Childe openly accepted the inherent subjectivity of archaeological interpretation, a stance in stark contrast to the processualists' insistence that archaeological interpretation could be objective. Consequently, Trigger considered Childe a "prototypical post-processual archaeologist."

Despite his global influence, Childe's work was often poorly understood in the United States, where his significant contributions to European prehistory never gained widespread recognition. As a result, in the United States, he erroneously acquired a reputation as primarily a Near Eastern specialist and a co-founder of neo-evolutionism, alongside figures like Julian Steward and Leslie White. This perception persisted despite the fact that Childe's own approach was "more subtle and nuanced" than theirs. Julian Steward, for instance, repeatedly misrepresented Childe as a unilinear evolutionist in his writings, perhaps as an attempt to differentiate his own "multilinear" evolutionary approach from the ideas of Marx and Engels. In contrast to this American neglect and misrepresentation, Trigger believed it was an American archaeologist, Robert McCormick Adams, Jr., who made the most significant posthumous advancements of Childe's "most innovative ideas." Furthermore, a small but notable group of American archaeologists and anthropologists in the 1940s did follow Childe, seeking to reintroduce materialist and Marxist ideas into their research after years during which Boasian particularism had been dominant within the discipline.

4. Personal Life

Vere Gordon Childe's personal life, while largely private, revealed a complex individual with deep convictions and unique social traits. His biographer, Sally Green, found no evidence that Childe ever engaged in a serious intimate relationship, and she presumed he was heterosexual as there was no indication of same-sex attraction. Conversely, his student Don Brothwell suggested that Childe might have been homosexual. Childe cultivated numerous friendships with individuals of both sexes, yet he remained characteristically "awkward and uncouth, without any social graces." Despite these difficulties in personal interaction, he enjoyed engaging and socializing with his students, often inviting them to dine with him. He was inherently shy and tended to conceal his personal feelings. Brothwell speculated that these personality traits might be indicative of undiagnosed Asperger syndrome.

Childe firmly believed that the study of the past could offer crucial guidance for human actions in the present and future. He was widely known for his radical left-wing views, having been a committed socialist since his undergraduate days. He served on the committees of several left-wing groups, though he generally avoided direct involvement in the intricate Marxist intellectual arguments within the Communist Party. With the notable exception of How Labour Governs, he typically refrained from committing his non-archaeological opinions to print; consequently, many of his political views are evident primarily through comments made in private correspondence. While Childe was considered liberal-minded on social issues and deplored racism, Colin Renfrew noted that he did not entirely escape the pervasive nineteenth-century view regarding distinct differences between various races. Trigger similarly observed racist elements in some of Childe's earlier culture-historical writings, including the suggestion that Nordic peoples possessed a "superiority in physique," although Childe later disavowed these ideas. In a private letter to archaeologist Christopher Hawkes, Childe candidly expressed that he "disliked Jews."

Childe was an avowed atheist and a sharp critic of religion, which he viewed as a form of false consciousness rooted in superstition and serving the interests of dominant elites. In his 1947 book History, he commented that "magic is a way of making people believe they are going to get what they want, whereas religion is a system for persuading them that they ought to want what they get." Despite this, he paradoxically regarded Christianity as superior to what he termed "primitive religion," stating that "Christianity as a religion of love surpasses all others in stimulating positive virtue." In a letter from the 1930s, he wrote that "only in days of exceptional bad temper do I desire to hurt people's religious convictions."

Childe was fond of driving cars, enjoying the "feeling of power" they afforded him. He often recounted a story of racing at high speed down Piccadilly, London, at three in the morning purely for enjoyment, only to be pulled over by a policeman. He also delighted in practical jokes and was rumored to carry a halfpenny in his pocket to trick pickpockets. On one occasion, he famously played a joke on delegates at a Prehistoric Society conference by lecturing on a satirical theory that the Neolithic monument of Woodhenge was built as an imitation of Stonehenge by a nouveau riche chieftain, with some audience members failing to grasp his tongue-in-cheek humor. He was proficient in several European languages, which he had taught himself during his early travels across the continent.

His other hobbies included walking in the British hillsides, attending classical music concerts, and playing the card game contract bridge. Childe was fond of poetry; his favorite poet was John Keats, and his favorite poems were William Wordsworth's "Ode to Duty" and Robert Browning's "A Grammarian's Funeral." While not particularly interested in novels, his favorite was D. H. Lawrence's Kangaroo (1923), a book that resonated with many of Childe's own feelings about Australia. He appreciated good quality food and drink, and regularly frequented restaurants. Childe was known for his battered, tatty attire. He invariably wore his wide-brimmed black hat-purchased from a hatter in Jermyn Street, central London-along with a tie, which was typically red, a color chosen to symbolize his socialist beliefs. He frequently wore a black Mackintosh raincoat, often carrying it over his arm or draped over his shoulders like a cape. In summer, he commonly wore shorts with socks, sock suspenders, and large boots.

5. Legacy and Influence

Vere Gordon Childe's passing marked the end of an era for European prehistory, yet his intellectual legacy continued to exert a profound and enduring impact on the discipline of archaeology.

5.1. Academic Assessment

Upon his death, Childe received widespread acclaim within the archaeological community. His colleague Stuart Piggott hailed him as "the greatest prehistorian in Britain and probably the world." Later, archaeologist Randall H. McGuire described him as "probably the best known and most cited archaeologist of the twentieth century," a view echoed by Bruce Trigger. Barbara McNairn further characterized him as "one of the most outstanding and influential figures in the discipline," while Andrew Sherratt asserted that Childe occupied "a crucial position in the history" of archaeology.

Sherratt highlighted Childe's prodigious output, noting that it was "massive by any standard." Over his career, Childe published more than twenty books and approximately 240 scholarly articles. Brian Fagan described his books as "simple, well-written narratives" that became "archaeological canon between the 1930s and early 1960s." By 1956, Childe was recognized as the most translated Australian author in history, with his works published in numerous languages, including Chinese, Czech, Dutch, French, German, Hindi, Hungarian, Italian, Japanese, Polish, Russian, Spanish, Swedish, and Turkish. As of 2005, archaeologists David Lewis-Williams and David Pearce considered Childe "probably the most written about" archaeologist in history, emphasizing that his books were still "required reading" for those in the discipline. As recently as 2024, the University of Sydney honored his legacy by naming the Vere Gordon Childe Centre in his name.

Childe himself believed his most original contributions were his "interpretative concepts and methods of explanation" rather than new data from excavations or chronological schemes. As he stated, "The most original and useful contributions that I may have made to prehistory are certainly not novel data rescued by brilliant excavation from the soil or by patient research from dusty museum cases, nor yet well founded chronological schemes nor freshly defined cultures, but rather interpretative concepts and methods of explanation." Sherratt further elaborated that "What is of lasting value in his interpretations is the more detailed level of writing, concerned with the recognition of patterns in the material he described. It is these patterns which survive as classic problems of European prehistory, even when his explanations of them are recognised as inappropriate."

Known as "the Great Synthesizer," Childe's primary academic renown stems from his groundbreaking synthesis of European and Near Eastern prehistory during a period when most archaeologists focused on regional sites and sequences. However, since his death, this comprehensive framework has undergone significant revision, largely due to the advent of new scientific methods like radiocarbon dating. Consequently, many of his specific interpretations have been "largely rejected," and numerous conclusions regarding Neolithic and Bronze Age Europe have been found to be incorrect. Despite this, Childe's theoretical work, largely overlooked during his lifetime, experienced a resurgence in the late 1990s and early 2000s, especially in Latin America, where Marxism continued to be a core theoretical current among archaeologists throughout the latter half of the 20th century.

Despite his global influence, Childe's work was often poorly understood in the United States, where his extensive scholarship on European prehistory never became widely known. As a result, in the United States, he erroneously acquired a reputation as primarily a Near Eastern specialist and a co-founder of neo-evolutionism, alongside figures such as Julian Steward and Leslie White. This perception persisted despite his approach being "more subtle and nuanced" than theirs. For instance, Steward repeatedly misrepresented Childe as a unilinear evolutionist in his writings, perhaps as an attempt to differentiate his own "multilinear" evolutionary approach from the ideas of Marx and Engels. In contrast to this American neglect and misrepresentation, Trigger believed it was an American archaeologist, Robert McCormick Adams, Jr., who did the most to posthumously develop Childe's "most innovative ideas." A smaller group of American archaeologists and anthropologists in the 1940s did follow Childe, advocating for the reintegration of materialist and Marxist ideas into their research after years during which Boasian particularism had been dominant within the discipline.

5.1.1. Academic conferences and publications

Following Childe's death, several articles were published examining his profound impact on archaeology. In 1980, Bruce Trigger's Gordon Childe: Revolutions in Archaeology explored the various influences on Childe's archaeological thought. The same year saw the publication of Barbara McNairn's The Method and Theory of V. Gordon Childe, which analyzed his methodological and theoretical approaches to archaeology. The subsequent year, Sally Green published Prehistorian: A Biography of V. Gordon Childe, in which she described him as "the most eminent and influential scholar of European prehistory in the twentieth century." Peter Gathercole hailed the works of Trigger, McNairn, and Green as "extremely important," while Ruth Tringham viewed them as part of a broader "let's-get-to-know-Childe-better" movement.

In July 1986, a colloquium dedicated to Childe's work was held in Mexico City, commemorating the 50th anniversary of the publication of Man Makes Himself. In September 1990, the University of Queensland's Australian Studies Centre organized a centenary conference for Childe in Brisbane, with presentations covering both his scholarly and socialist contributions. In May 1992, another conference marking his centenary was held at the UCL Institute of Archaeology in London, co-sponsored by the Institute and the Prehistoric Society, both organizations he had formerly led. The proceedings of this conference were published in a 1994 volume edited by David R. Harris, the Institute's director, titled The Archaeology of V. Gordon Childe: Contemporary Perspectives. Harris stated that the book aimed to "demonstrate the dynamic qualities of Childe's thought, the breadth and depth of his scholarship, and the continuing relevance of his work to contemporary issues in archaeology." In 1995, another collection of conference papers was published, titled Childe and Australia: Archaeology, Politics and Ideas, edited by Peter Gathercole, T. H. Irving, and Gregory Melleuish. Further academic papers on Childe appeared in subsequent years, delving into subjects such as his personal correspondences and his final resting place. Bruce Trigger noted that while Childe may not have provided answers that modern archaeologists find satisfactory, he "challenged colleagues of his own and succeeding decades by constructing a vision of archaeology that was as broad as that of other social sciences, but which also took account of the particular strengths and limitations of archaeological data."

5.2. Image in Popular Culture

Vere Gordon Childe's enduring influence extended beyond academic circles into popular culture. Notably, his work and persona were referenced in the 2008 blockbuster film Indiana Jones and the Kingdom of the Crystal Skull, where the fictional archaeologist Indiana Jones is depicted as having been influenced by Childe.

6. Selected Publications

Vere Gordon Childe was a prolific author, publishing numerous influential works throughout his career.

| Title | Year | Publisher |

|---|---|---|

| The Most Ancient East | 1922, 1928 | Kegan Paul (London) |

| How Labour Governs: A Study of Workers' Representation in Australia | 1923 | The Labour Publishing Company (London) |

| The Dawn of European Civilization | 1925 | Kegan Paul (London) |

| The Aryans: A Study of Indo-European Origins | 1926 | Kegan Paul (London) |

| The Most Ancient East: The Oriental Prelude to European Prehistory | 1929 | Kegan Paul (London) |

| The Danube in Prehistory | 1929 | Oxford University Press (Oxford) |

| The Bronze Age | 1930 | Cambridge University Press (Cambridge) |

| Skara Brae: A Pictish Village in Orkney | 1931 | Kegan Paul (London) |

| The Forest Cultures of Northern Europe: A Study in Evolution and Diffusion | 1931 | Royal Anthropological Institute of Great Britain and Ireland (London) |

| The Continental Affinities of British Neolithic Pottery | 1932 | Royal Anthropological Institute of Great Britain and Ireland (London) |

| Skara Brae Orkney. Official Guide | 1933, Second Edition 1950 | His Majesty's Stationery Office (Edinburgh) |

| New Light on the Most Ancient East: The Oriental Prelude to European Prehistory | 1934 | Kegal Paul (London) |

| The Prehistory of Scotland | 1935 | Kegan Paul (London) |

| Man Makes Himself | 1936, slightly revised 1941, 1951 | Watts (London) |

| Prehistoric Communities of the British Isles | 1940, second edition 1947 | Chambers (London) |

| What Happened in History | 1942 | Penguin Books (Harmondsworth) |

| The Story of Tools | 1944 | Cobbett (London) |

| Progress and Archaeology | 1944 | Watts (London) |

| Scotland before the Scots, being the Rhind lectures for 1944 | 1946 | Methuen (London) |

| History | 1947 | Cobbett (London) |

| Social Worlds of Knowledge | 1949 | Oxford University Press (London) |

| Prehistoric Migrations in Europe | 1950 | Aschehaug (Oslo) |

| Magic, Craftsmanship and Science | 1950 | Liverpool University Press (Liverpool) |

| Social Evolution | 1951 | Schuman (New York) |

| Illustrated Guide to Ancient Monuments: Vol. VI Scotland | 1952 | Her Majesty's Stationery Office (London) |

| Society and Knowledge: The Growth of Human Traditions | 1956 | Harper (New York) |

| Piecing Together the Past: The Interpretation of Archeological Data | 1956 | Routledge and Kegan Paul (London) |

| A Short Introduction to Archaeology | 1956 | Muller (London) |

| The Prehistory of European Society | 1958 | Penguin (Harmondsworth) |