1. Names and Aliases

Takasugi Shinsaku used numerous names and aliases throughout his life, often to conceal his revolutionary activities from the Tokugawa Shogunate. His formal given name (imina) was 春風HarukazeJapanese. His common name (tsūshō) was Shinsaku, which is the name by which he is most widely known today. Other common names he used included 東一TōichiJapanese and 和助WasukeJapanese. His courtesy name (azana) was 暢夫ChōfuJapanese.

He adopted many literary names (gō and yagō), reflecting his various life stages and philosophies. Among the most famous are 東行TōgyōJapanese (meaning "Journey to the East"), which he adopted after shaving his head and becoming a monk-like figure, and 東行狂生Tōgyō KyōseiJapanese (Madman of the East Journey). Other aliases included 楠樹小史Nanju KōshiJapanese, 西海一狂生Saikai IkkyōseiJapanese (The Single Madman of the Western Sea), 東洋一狂ōseiJapanese (The Single Madman of the Orient), 些々生SasashōJapanese, 黙生MokusshōJapanese, 市隠生IchīnsseiJapanese, 研海Ken KaiJapanese, and 赤間隠人Akama KakujinJapanese (Hermit of Akama).

For clandestine activities, he employed several pseudonyms (henmei), such as 谷潜蔵Tani SenzoJapanese, 谷梅之助Tani UmenosukeJapanese, 谷梅之進Tani UmenosukeJapanese, 備後屋助一郎Bingoya SukeichirōJapanese, 備後屋三郎Bingoya SaburōJapanese, 三谷和助Mitani WasukeJapanese (or 和介WasukeJapanese), 祝部太郎Iwai TaroJapanese, 宍戸刑馬Shishido GyomaJapanese, and 西浦松助Nishiura MatsusukeJapanese. He later formally changed his name to 谷潜蔵Tani SenzoJapanese.

2. Early Life

Takasugi Shinsaku's early life laid the foundation for his later radical and reformist activities that shaped the Bakumatsu period.

2.1. Birth and Upbringing

Takasugi Shinsaku was born on September 27, 1839 (Tenpō 10, August 20 by the lunisolar calendar), in the castle town of Hagi, the capital of the Chōshū Domain (present-day Yamaguchi Prefecture). He was the eldest son of Takasugi Kochūta, a middle-ranked samurai with an income of 200 koku (a measure of rice), and his mother, Michi (道MichiJapanese), daughter of Ōnishi Shōsō. He had three younger sisters named Tomo (智TomoJapanese), Sachi (幸SachiJapanese), and Mei (明MeiJapanese), but he was the only male heir, leading to a strict upbringing as the family's successor.

At the age of ten, Takasugi contracted smallpox. Thanks to the dedicated care of his grandparents and family, he survived, but the illness left pockmarks on his face, earning him the nickname "azukimochi" (red bean rice cake). His birthplace in Kikuyakochō, Hagi, is today a significant historical site, where elements like a memorial stele and a well from his time are preserved within its grounds.

The historic Kikuya Lane near Takasugi's birthplace offers a glimpse into the traditional environment of his youth.

2.2. Education and Encounter with Yoshida Shōin

Takasugi's formal education began at the private Chinese classics academy (Yoshimatsu-juku) before he entered the domain's official school, Meirinkan, in 1852. He also trained in Yagyū Shinkage-ryū swordsmanship, eventually achieving a master's license in the art.

In 1857, a pivotal moment in his intellectual development occurred when he enrolled in the Shōka Sonjuku, a renowned private academy led by Yoshida Shōin. Takasugi quickly became one of Yoshida's favorite students, earning a place among the "Shōka Sonjuku Four Heavenly Kings" alongside Kusaka Genzui, Yoshida Toshimaro, and Irie Kuichi. Yoshida Shōin recognized Takasugi's extraordinary intellect and unique character, though he often praised Kusaka Genzui to push Takasugi to apply himself more diligently, a tactic that proved effective in fostering Takasugi's competitive spirit and academic growth.

In January 1860, Takasugi married Inoue Masa (1845-1922), the second daughter of Inoue Heiemon, a Yamaguchi retainer and magistrate with an income of 250 koku, and a friend of Takasugi's father. Masa was celebrated as the most beautiful woman in the provinces of Suō and Nagato. Their marriage was arranged by his parents, who hoped it would help him move past the grief of his teacher's execution and settle into a stable life.

2.3. Studies in Edo and Early Activities

In 1858, by command of his domain, Takasugi traveled to Edo (modern-day Tokyo) for further studies. He attended the Shōheikō, a military school under the direct control of the shōgun, and also studied at Ōhashi Totsuan's Ōhashi-juku. In 1859, when his teacher Yoshida Shōin was arrested during the Ansei Purge, Takasugi visited him in jail, even providing care. However, he was ordered to return to Hagi by his domain, and Shōin was executed shortly after, on November 21, 1859.

In March 1861, Takasugi left home again to undergo naval training aboard the domain's warship, the Heishinmaru (丙辰丸HeishinmaruJapanese), traveling to Edo. He further honed his swordsmanship at the Shintō Munen-ryū Renpeikan dojo (神道無念流Shintō Munen-ryūJapanese). Later, in August of the same year, he embarked on a study trip to the Tōhoku region, where he formed connections with influential contemporary thinkers such as Sakuma Shōzan and Yokoi Shōnan. These experiences deepened his understanding of both traditional Japanese arts and the broader political and intellectual currents of his time.

3. Foreign Experience and Ideological Shift

Takasugi Shinsaku's visit to Shanghai in 1862 was a watershed moment that profoundly reshaped his worldview and ideology, fueling his conviction that Japan urgently needed radical modernization to avoid colonial subjugation.

Despite Japan's policy of national isolation during the Edo period, Takasugi was secretly dispatched by the Chōshū Domain in January 1862 to Shanghai in the Great Qing Empire. His mission was to investigate the state of affairs and assess the strength of the Western powers. Before departing for Shanghai, Takasugi visited Nagasaki, where he met American missionaries like Channing Williams (founder of Rikkyo University) and Guido Verbeck. From them, he gained crucial insights into global affairs, including the American Civil War and the ongoing internal strife in the Qing Empire. His travelogue, the Yūshin Goroku (遊清五録Records of a Trip to Qing ChinaJapanese), notes his learning about political systems like presidential systems from Williams. He also studied English and visited American, French, and Portuguese consuls in Nagasaki, writing to his father of his desire to serve the domain.

Takasugi sailed from Nagasaki aboard the shogunate's ship, the Chitosemaru, on May 27, 1862 (April 29 by the lunisolar calendar), alongside figures like Godai Tomoatsu. He arrived in Shanghai on June 3 (May 6 by the lunisolar calendar). His two-month stay in Shanghai coincided with the ongoing Taiping Rebellion, and he was shocked by the extent of European imperialism's impact on China, witnessing firsthand how the Qing Empire was succumbing to Western dominance.

Upon his return to Nagasaki on August 9, 1862 (July 14 by the lunisolar calendar), Takasugi was deeply convinced that Japan must rapidly strengthen itself, particularly its military, to avoid a similar fate. This realization coincided with the surging Sonnō Jōi ('Revere the Emperor, Expel the Barbarians') movement within Japan. While initially advocating for the expulsion of foreigners, Takasugi's foreign experience led him to conclude that direct confrontation was futile. Instead, Japan needed to learn Western military tactics, technologies, and political systems to become strong enough to defend itself. This ideological shift transformed the Sonnō Jōi movement from a purely anti-foreign stance into an anti-Tokugawa bakufu movement, as Takasugi believed the Shogunate's weak policies prevented Japan from modernizing effectively.

4. Sonnō Jōi Movement and Military Reforms

Takasugi Shinsaku was a central and often radical figure in the Sonnō Jōi movement during the Bakumatsu period, and his innovative military reforms profoundly influenced the course of Japan's modernization.

4.1. Involvement in Sonnō Jōi and Radical Actions

Even at a young age, Takasugi became one of the most extreme proponents of the Sonnō Jōi policy within Chōshū. During Takasugi's voyage to Shanghai, the more conservative faction led by Nagai Uta was purged in Chōshū, and the Sonnō Jōi faction gained prominence. Takasugi joined this movement, working alongside Katsura Kogorō (later Kido Takayoshi) and Kusaka Genzui, and actively promoted reverence for the Emperor and the expulsion of foreigners in Edo and Kyoto, interacting with patriots from various domains.

In 1862, Takasugi argued that while the Satsuma Domain had demonstrated its resolve by killing foreigners in the Namamugi Incident, Chōshū was still advocating for Kōbu Gattai (Union of Court and Shogunate). He contended that Chōshū must take concrete action to expel barbarians, even if the domain government refused to do so. This led to a plan to assassinate foreign envoys in Kanazawa, Edo, but the plot was thwarted by Prince Mōri Sadahiro after Takechi Hanpeita of the Tosa Domain informed him. Takasugi was subsequently ordered to confine himself.

On December 12, 1862, in protest against the Shogunate's defiance of the Imperial court's wishes, Takasugi participated with his comrades in the burning of the British Legation under construction at Gotenyama, Shinagawa. After this incident, while other comrades headed to Kyoto, Takasugi remained in Edo to arrange for Yoshida Shōin's reburial. When summoned to Kyoto, he declined the role of a negotiator for the Imperial Court, a position the domain intended for him, and instead requested a ten-year leave. The next day, he shaved his head and adopted a monastic appearance, taking the alias 東行TōgyōJapanese (Journey to the East), symbolizing his retreat and determination to act independently. He then returned to Hagi, moving with his wife and a maid into a small rented house in Matsumoto village, Yoshida Shōin's birthplace.

4.2. Formation of the Shotai and Kiheitai

Takasugi Shinsaku is celebrated for originating the revolutionary concept of auxiliary irregular militia units, known as Shotai (諸隊ShotaiJapanese). Under the traditional feudal system, military service and weapon ownership were exclusive to the samurai class. Takasugi boldly challenged this centuries-old hierarchy by advocating for the recruitment of commoners into new, socially-mixed paramilitary units. These units broke away from the rigid class structure, as recruitment and promotion were not (at least in theory) dependent on social status. Farmers, merchants, carpenters, sumo wrestlers, and even Buddhist priests were enlisted, although samurai often still formed the majority in most Shotai.

Takasugi astutely recognized that leveraging the financial resources of the burgeoning merchant and farmer classes could significantly augment the domain's military strength without unduly burdening its traditional samurai-based finances. As the Chōshū leaders were hesitant to completely restructure the domain's social fabric, this limited but effective integration of commoners allowed for the formation of a modern military force without immediate social upheaval.

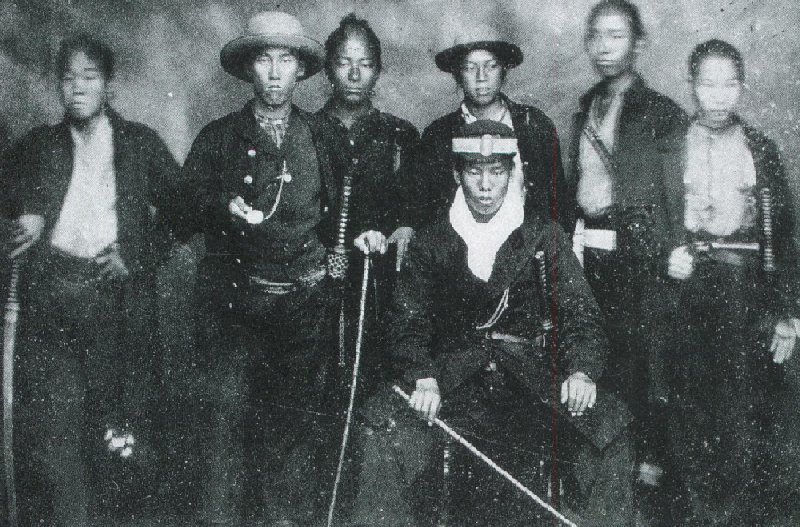

In June 1863, Takasugi personally founded a specialized Shotai unit under his direct command: the Kiheitai (奇兵隊KiheitaiJapanese, Irregular Troops). Initially based at Amidaji Temple (next to Akama Shrine) in Shimonoseki, this unit consisted of 300 soldiers, approximately half of whom were samurai. The Kiheitai became the vanguard of Chōshū's modern military, embodying Takasugi's vision of a merit-based, socially inclusive army. However, just two months after its formation, Takasugi was dismissed as the Kiheitai's leader in September, held accountable for the Kyohoji Incident of August 16, which involved a conflict between Kiheitai and Senkitai forces that resulted in two deaths and the forced seppuku of an inspecting officer. Despite his dismissal, the Kiheitai continued to be a powerful force under new leadership, including Yamagata Aritomo.

5. Turmoil of the Bakumatsu Period and Major Activities

Takasugi Shinsaku played a pivotal and often decisive role amidst the escalating crises and conflicts that ultimately led to the demise of the Tokugawa Shogunate and the Meiji Restoration.

5.1. Shimonoseki Campaign and Peace Negotiations

Following Chōshū's aggressive act of firing upon Western warships in the Straits of Shimonoseki on June 25, 1863, a retaliatory strike came in the summer of 1864. Naval forces from Britain, France, the Netherlands, and the United States bombarded Shimonoseki, Chōshū's main port, in what became known as the Bombardment of Shimonoseki. French marines subsequently landed and engaged Chōshū units, demonstrating the stark inferiority of traditional Japanese forces against modern Western armies.

This humiliating defeat convinced Chōshū's leaders of the urgent need for comprehensive military reform. Recognizing Takasugi's strategic genius and diplomatic capabilities, he was pardoned from his earlier imprisonment (for illegally leaving the domain) and reinstated. At just 25 years old, he was entrusted with the critical task of negotiating peace with the four Western powers and appointed 'Director of Military Affairs' to oversee military modernization.

In the peace negotiations, Takasugi refused the allies' demands for the lease of Hikoshima and insisted that the payment of indemnities be shouldered by the Shogunate rather than the Chōshū Domain. Accounts vary, but some suggest he skillfully obfuscated the land lease issue by reciting passages from the Kojiki, ensuring Hikoshima would not become a colonial outpost like Hong Kong Island or Kowloon Peninsula. His steadfastness and diplomatic acumen during this critical period averted a potential colonial fate for a strategic Japanese territory. This experience solidified Takasugi's conviction that direct confrontation with foreign powers was not feasible, and Japan's survival depended on adopting Western military technology and strategies.

5.2. Kōzanji Uprising and Chōshū Civil War

The aftermath of the Bombardment of Shimonoseki and the First Chōshū expedition by the Shogunate (autumn 1864) saw a power struggle within the Chōshū Domain. Conservative forces, known by Takasugi as the "commoner faction" (俗論派zokuron-haJapanese), gained ascendancy, favoring conciliation with the Shogunate to preserve the domain. This led to the persecution and execution of many reformist (正義派seigi-haJapanese) leaders who advocated for continued resistance. Takasugi, branded an outcast by the commoner faction, fled to Fukuoka in Kyushu with about a dozen followers, including future Meiji leaders Yamagata Aritomo, Itō Hirobumi, and Inoue Kaoru.

However, hearing of the executions of his comrades, Takasugi secretly returned to Shimonoseki. On December 15, 1864 (November 17, Genji 1 by lunisolar calendar), he initiated the Kōzanji Uprising. Leading forces such as Itō Hirobumi's Rikishitai (力士隊RikishitaiJapanese, Sumo Wrestler Unit) and Kawase Masaoka's Yūgekitai (遊撃隊YūgekitaiJapanese, Guerrilla Unit) from Kōzan-ji Temple, he launched a swift military campaign against the commoner faction. The Kiheitai and other auxiliary units soon joined his cause. Through a series of rapid strikes and with crucial support from Katsura Kogorō, Takasugi achieved a decisive victory by March 1865, effectively purging the conservative elements and seizing control of the domain's administration. This triumph re-established the reformist faction's dominance and positioned Takasugi as a key arbiter of Chōshū's policies.

5.3. Command in the Second Chōshū Expedition and Victory

With the reformists in power, Takasugi devoted himself to further military modernization, focusing on importing Western arms and raising more troops. These efforts culminated in the Second Chōshū expedition (also known as the Four Fronts War) in June 1866, when the Tokugawa Shogunate launched a second punitive expedition against Chōshū.

Takasugi was appointed naval commander, leading the modernized Chōshū fleet, including the steamship Hei'inmaru (丙寅丸Hei'inmaruJapanese, also known as Otentosama Maru), which he had purchased in Nagasaki. He displayed outstanding leadership and strategic command. In the Ōshima Mouth Campaign, the Hei'inmaru launched a surprise attack on the Shogunate's ships, the Asahimaru and Yakumo-maru, though with limited immediate success. However, Takasugi's forces, including the Kiheitai and Hōkokutai, successfully landed at Moji and Tanoura, driving back the Shogunate's army.

Despite initial stalemates, the tide turned dramatically on July 20, 1866 (June 9 by lunisolar calendar), with the sudden death of Tokugawa Iemochi, the 14th Shogun. This event demoralized the Shogunate forces. By July 30, various allied domains like Higo Domain, Kurume Domain, Yanagawa Domain, Karatsu Domain, and Nakatsu Domain began to withdraw. Shogunate commander Ogasawara Nagamichi fled by sea from Kokura, leaving the Kokura Domain to burn down Kokura Castle on August 1 and retreat.

The Shogunate's defeat was decisive, discrediting its military power and severely undermining its authority. Takasugi's "nation in arms" approach had created a military force far exceeding Chōshū's relatively small size. This victory paved the way for traditionally rival domains like Satsuma to form an alliance with Chōshū, leading to the decisive battles that eventually brought about the Meiji Restoration in 1868.

6. Personal Life

Takasugi Shinsaku's personal life, though often overshadowed by his intense political and military activities, included significant relationships and family responsibilities.

In January 1860, Takasugi married Inoue Masa (1845-1922), the second daughter of Inoue Heiemon. Their marriage was arranged by his parents, who hoped it would provide stability after the execution of his revered teacher, Yoshida Shōin. Masa was renowned for her beauty and was considered the most beautiful lady in the provinces of Suō and Nagato.

Takasugi also had a relationship with a geisha named O-Uno (おうのO-UnoJapanese, 1843-1909), also known as Tani Baisho. He encountered her at a brothel in Akamaseki, Shimonoseki, while in hiding from assassins. O-Uno remained his mistress and was a significant presence in his later life, nursing him during his final illness.

Takasugi and Masa had one son, Takasugi Tōichi (高杉東一Takasugi TōichiJapanese, also known as Takasugi Umenoshin) (1864-1913). In February 1867, Masa and their three-year-old son traveled from Hagi to Shimonoseki to visit Takasugi as his health deteriorated. Due to Masa's presence, O-Uno initially left and became a Buddhist nun, but Masa later summoned her back to help care for him. However, as Takasugi's illness worsened dramatically in March 1867, Masa and Tōichi were sent back to Hagi, while O-Uno (Baisho) and the Buddhist nun and poet Nomura Bōtō remained with him until his death.

After Takasugi's death, his young son Tōichi was taken under the care of Kido Takayoshi (formerly Katsura Kogorō) and his wife Matsuko in 1871. Takasugi's main family line was continued by Takasugi Haruki, who married Takasugi's youngest sister, Mitsu, and inherited the family headship.

7. Ideology and Character

Takasugi Shinsaku's ideology and character were marked by a striking blend of radical pragmatism, fierce determination, and an unconventional approach to life. He was a visionary who understood the need for Japan to adapt to new global realities while fiercely defending its sovereignty.

7.1. Quotations and Sayings

Takasugi is known for several powerful sayings and poems that reflect his philosophy:

- "To die when one should die, and to live when one should live, that is the way of heroes and great men. For two or three years, one should not act rashly, but devote oneself to study. During that time, the moment for a hero to die will surely come."

- "A hero is one who, in times of no turmoil, hides as a beggar or a pauper. But when turmoil arises, he must act like a dragon."

- "A man must never say 'I'm troubled.' My father always told me this sternly. To say 'I'm troubled' is to be on the verge of death. No matter how difficult the situation, if you face it with the spirit of 'I am not troubled at all,' a path will naturally open. There is always an escape route in any predicament. It's like finding a bend in the road when you hit a dead end. If you face things with the absolute spirit of 'I am not troubled,' a way will surely be made. Therefore, never utter the single word 'troubled'."

His most famous poem, often mistakenly cited as his death poem, is:

: おもしろきこともなき世を面白くOmoshiroki koto mo naki yo o omoshirokuJapanese

: すみなすものは心なりけりSuminasu mono wa kokoro nari keriJapanese

This translates roughly to:

: "To make interesting this uninteresting world,"

: "What makes it so is the heart."

There is a long-standing debate over whether the second line should contain をoJapanese or にniJapanese (meaning "in" or "to"). While some monuments use "ni," a historical manuscript from the Takasugi family, Tōgyō Ikō, which is believed to be a copy of Takasugi's original, uses "ni." It is also widely believed that the second line, "What makes it so is the heart," was added by Nomura Bōtō, who was nursing him. Recent research indicates that this poem was actually written in 1866, the year before his death, suggesting it was not his final death poem.

Another popular poem, often attributed to Takasugi (though some sources suggest Kido Takayoshi as the author), is the Dodoitsu (都々逸DodoitsuJapanese, a type of Japanese folk song):

: 三千世界の鴉を殺し、主と添寝がしてみたいSanzen sekai no karasu o koroshi, nushi to soine ga shitemitaiJapanese

This translates to: "Kill all the crows in three thousand worlds, and I wish to sleep beside you." This poem is still sung in Hagi folk songs like "Otoko Nara" and "Yoishokosho Bushi."

7.2. Personality and Philosophy

Takasugi Shinsaku possessed a unique and multifaceted personality that defied conventional samurai norms. His teacher, Yoshida Shōin, quickly recognized his extraordinary talent, even as he feigned praise for other students like Kusaka Genzui to motivate Takasugi, a tactic that successfully ignited Takasugi's ambition and academic prowess.

Takasugi was known for his unconventional and often flamboyant behavior. Unlike the austere Kusaka Genzui, who lived humbly with his soldiers, Takasugi often stayed outside military encampments and was known to bring his favorite geisha into the camp, even under an umbrella. Yet, despite these differences, both commanders commanded equal respect and loyalty from their troops.

He had a disregard for the strict separation of public and private funds, even attempting to purchase warships twice using domain money. This suggests a focus on the grander goal of national strengthening over meticulous financial protocol. An anecdote highlights his strong sense of dignity: after showing his sword-the "soul of a samurai"-to a British soldier who repeatedly asked to see it out of curiosity, Takasugi refused to show it again, feeling it had been treated disrespectfully.

There is also an anecdote that Takasugi gifted Sakamoto Ryōma a Smith & Wesson Model 2 Army revolver, caliber .33, which he allegedly purchased in Shanghai. While Ryōma's letters confirm receiving a pistol from Takasugi, there is no definitive proof it was the one bought in Shanghai. Some historians suggest it could have been a pistol smuggled into Chōshū, where Takasugi also acquired weapons.

Takasugi's pragmatism and foresight were exceptional. Itō Hirobumi later famously remarked that had Takasugi accepted the Western powers' demands for the lease of Hikoshima, it would have become a colony like Hong Kong, and Shimonoseki would have become like Kowloon. This underscores Takasugi's profound understanding of imperialistic designs.

Contemporaries like Miura Gorō described him as a truly great man, remarkably astute and quick-witted, with an unparalleled ability to improvise and strategize. Miura believed Takasugi's "ghostly stratagems and divine calculations" were beyond the reach of ordinary men, even surpassing Saigō Takamori in strategic genius. Takasugi's ability to maintain composure and humor in the face of adversity, even bringing tea sets or a shamisen into military camps, was seen as evidence of his depth and an embodiment of his philosophy to "make interesting this uninteresting world." He encouraged younger men to "learn foolishness," interpreting it as the Confucian idea of "possessing wisdom but appearing foolish," a caution against youthful arrogance.

8. Death

Takasugi Shinsaku did not live to witness the full realization of his revolutionary goals. His health began to severely decline in October 1866, when he contracted tuberculosis. He was moved to a residence in Sakurayama-chō, Shimonoseki, where he was cared for by his mistress O-Uno (Tani Baisho) and the Buddhist nun and poet Nomura Bōtō.

Around February 1867, his wife Masa and their three-year-old son, Takasugi Tōichi (Umenoshin), arrived from Hagi to visit him. Out of respect for Masa, O-Uno initially left and became a Buddhist nun, but Masa later requested her return to assist with Takasugi's care. However, as Takasugi's illness worsened dramatically in March 1867, Masa and Tōichi were sent back to Hagi, while Baisho and Nomura Bōtō remained by his side.

Takasugi Shinsaku died shortly thereafter, on May 17, 1867 (April 14, Keiō 3 by lunisolar calendar), in Shinchi-chō, Shimonoseki. He was only 27 years old (29 by traditional Japanese reckoning). Accounts vary regarding who was present at his deathbed, but his father, mother, wife, and son were said to have been there, along with Nomura Bōtō, Yamagata Aritomo, and Tanaka Mitsuaki (though Tanaka's diary indicates he was in Kyoto on that day). The discrepancy in the official death date (April 14 vs. April 13) is believed to be due to the need for time to process his son Tōichi's inheritance of the Tani family.

Per his will, Takasugi was buried near the Kiheitai's camp at Mount Kiyomizu in Yoshida. His dream of overthrowing the Tokugawa Shogunate, clearly embodied in his alias Tōgyō (Journey to the East), was realized just a year later with the Meiji Restoration.

9. Legacy and Assessment

Takasugi Shinsaku is revered as a pivotal figure of the early Meiji Restoration, recognized for his exceptional military acumen, political insight, and progressive social reforms.

9.1. Historical Significance and Impact

Despite his untimely death at the age of 27, Takasugi's contributions were transformative. He is celebrated for his crucial role in undermining the Tokugawa Shogunate's authority, particularly through his strategic leadership in the Second Chōshū Expedition, which exposed the Shogunate's military weakness and galvanized anti-Bakufu sentiment among other powerful domains like Satsuma.

His most enduring legacy is the establishment of the Kiheitai and other auxiliary units. By actively recruiting commoners-farmers, merchants, artisans, and even priests-into these modern, socially-mixed paramilitary forces, Takasugi fundamentally challenged the rigid feudal class system. This innovative approach not only significantly augmented Chōshū's military capabilities without straining its finances but also provided a blueprint for the later creation of the Imperial Japanese Army and the system of universal conscription. His vision of a merit-based army, rather than one determined by inherited status, laid crucial groundwork for Japan's rapid modernization and social mobility during the Meiji era.

In his hometown of Hagi, Yamaguchi Prefecture, Takasugi is remembered as a mystical and energetic hero who dedicated his efforts to opening the path for modernization, Westernization, and reforms, not only in military affairs but also in political and social structures.

9.2. Assessments by Contemporaries

Takasugi Shinsaku was highly regarded by his contemporaries, who recognized his unique talents and profound influence:

- Yoshida Shōin: His teacher, Shōin, famously stated, "He is a man of foresight. However, he does not apply himself to scholarship. Also, he has a strong habit of acting on his own will and being self-important. I once praised Genrui to curb Shinsaku. Shinsaku was very displeased. Not long after, Shinsaku's scholarship rapidly advanced, and his arguments became increasingly profound. All his comrades deferred to him. Whenever I discussed matters, I often brought in Shinsaku to decide them. His words were often not to be trifled with." Shōin further noted, "His keen insight is beyond my reach," and "Takasugi, ten years younger than me, lacks in scholarship and experience. Nevertheless, his strong character and clear insight excel beyond ordinary men."

- Kido Takayoshi: (Formerly Katsura Kogorō) described him as a "brilliant young man," but lamented, "It is regrettable that he has a somewhat stubborn nature. In the future, he will probably not tolerate criticism. If you (Shōin) had noted that point early and taught him, it would surely benefit his future."

- Kusaka Genzui: His close comrade, recognized Takasugi's brilliance, saying, "His deliberation is meticulous, his talent is unparalleled in this era," and "Shinsaku is ultimately beyond my reach." Irie Kuichi noted that while Kusaka lived humbly with his soldiers, Takasugi often stayed outside camps, occasionally bringing a geisha. However, both commanded equal respect.

- Itō Hirobumi: Later a Prime Minister, famously remarked, "When he moved, it was like thunder and lightning; when he spoke, it was like wind and rain. All eyes were astonished; none dared to look him directly. Was this not our Tōgyō, Takasugi-kun?" He also compared Takasugi to Saigō Takamori, stating, "I believe he was of the same type as Saigō Nanshū. He was a brave and resolute man, very rich in entrepreneurial talent."

- Yamagata Aritomo: Who inherited command of the Kiheitai, believed, "If Takasugi, who already stood out from the crowd at that time, were alive today, he would likely be superior to them (Itō and Inoue)."

- Yamada Akiyoshi: Praised his "majestic presence and heroic spirit, which still remain in my eyes." He wondered what more Takasugi could have achieved if he had lived to serve the enlightened Meiji government.

- Nakaoka Shintarō: Stated, "He has courage, does not falter when facing troops, acts when he sees an opportunity, and overcomes others with cunning. Takasugi Tōgyō (Shinsaku) is also an extraordinary talent in Kyoto."

- Katsu Kaishū: Described him as "young, but because of the times, he couldn't fully demonstrate his abilities, but he was a man of strong vitality."

- Tanaka Mitsuaki: Hailed Takasugi as "Takasugi, who wielded troops like a demon god; Takasugi, the elusive hero in action; Takasugi, the extraordinary dashing man." He also noted, "His strategies were varied and elusive; every single action he took became a vanguard for the nation, inspiring not only the spirit of the entire domain but also serving as a leader for revolutionaries nationwide." Tanaka even stated, "I knew all three great heroes of the Restoration. I also met Sakamoto Ryōma, Takechi Hanpeita, Nakaoka Shintarō, and many other famous senior figures. However, the one who stood out toweringly was Takasugi."

- Miura Gorō: Expressed immense admiration, stating, "Takasugi Shinsaku was truly a great man. The only person I've ever thought was great is this Takasugi. He was incredibly quick-witted and sharp, resourceful, and ingenious. ...His demonic schemes and divine calculations were far beyond what ordinary people could achieve. Saigō the Great is said to be great, but Takasugi was on a different level." Miura also cherished Takasugi's unconventional traits, such as performing tea ceremonies or playing the shamisen in the battlefield, seeing deep meaning in them.

10. Monuments and Memorials

Several monuments and memorials commemorate Takasugi Shinsaku, reflecting his enduring significance in Japanese history.

His grave is located at Tōgyō-an (東行庵Tōgyō-anJapanese, Tōgyō Hermitage) in Yoshida, Shimonoseki, Yamaguchi Prefecture. This hermitage, named after Takasugi's alias, was built in 1884 with funds raised by his friends and comrades, including Yamagata Aritomo, Yamada Akiyoshi, Itō Hirobumi, and Inoue Kaoru. Tani Baisho (O-Uno), Takasugi's former mistress and nun, resided there and looked after his grave until her death in 1909. A grave inscription stone carved with Takasugi's dying wishes was erected there in April 2016. The grave itself was designated a National Historic Monument in 1934.

Takasugi is also enshrined at Tokyo Shōkonsha (now Yasukuni Shrine) alongside other prominent figures of the Meiji Restoration, such as Yoshida Shōin, Kusaka Genzui, Sakamoto Ryōma, and Nakaoka Shintarō, by figures like Kido Takayoshi and Ōmura Masujirō. Additionally, statues of Takasugi Shinsaku can be found in various locations, including one commemorating the Kōzanji Uprising in Shimonoseki.

11. Court Rank

In recognition of his contributions to the Meiji Restoration, Takasugi Shinsaku was posthumously granted the court rank of Shōshi'i (正四位Shōshi'iJapanese, Senior Fourth Rank) on April 8, 1891.

12. In Popular Culture

Takasugi Shinsaku's dramatic life and pivotal role in the Bakumatsu period have made him a popular figure in modern Japanese culture, appearing in various media:

- Manga and Anime**:

- He is a secondary character in the manga and anime Rurouni Kenshin and its OAV adaptation Samurai X: Trust & Betrayal. Portrayed as critically ill, he recruits the young Himura Kenshin into the Kiheitai before Kido Takayoshi (Katsura Kogorō) makes Kenshin the Hitokiri Battōsai. He expresses concern over Kenshin's potential corruption.

- Takasugi Shinsuke, a main antagonist in the manga series Gin Tama, is inspired by Takasugi Shinsaku.

- A highly fictionalized version of Takasugi appears in the PlayStation Portable game Bakumatsu Rock and its anime adaptation, where he is depicted as the bass player in a rock band led by Sakamoto Ryōma.

- He is the protagonist in the anime Bakumatsu, voiced by Yuuichi Nakamura.

- He is a protagonist in the manga Sidooh by Takashi Tsutomu.

- Film and Television**:

- Takasugi Shinsaku is frequently portrayed in NHK's annual Taiga drama series that cover the Meiji Restoration era. Recent instances include:

- Ryōmaden (2010), played by Yusuke Iseya.

- Hana Moyu (2015), played by Kengo Kora.

- He was played by Yujiro Ishihara in the 1957 film Sun in the Last Days of the Shogunate.

- Takasugi Shinsaku is frequently portrayed in NHK's annual Taiga drama series that cover the Meiji Restoration era. Recent instances include:

- Video Games**:

- He appears as an Archer class Servant in the mobile game Fate/Grand Order.

- He is the starting general of the Choshu clan in the real-time strategy game Shogun 2: Fall of the Samurai, which also features the Kiheitai as the clan's unique elite unit.

- Takasugi Shinsaku is a playable character in the 2024 action RPG Rise of the Ronin.

- Other**:

- He is credited with the aphorism "Live a pleasant life in the unpleasant world" in the manga Natsuyuki Rendezvous.

- One of the two buses operated by the Hagi City community bus, "Hagi Junkan Maarubasu," is named "Shinsaku-kun."