1. Overview

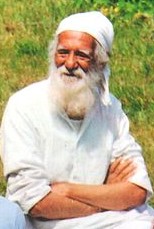

Sunderlal Bahuguna (1927-2021) was a prominent Indian environmentalist and a central figure in the Chipko movement, which championed the preservation of forests in the Himalayas. His activism was deeply rooted in Gandhian principles of nonviolence and Satyagraha, advocating for social solidarity and environmental protection against the backdrop of large-scale development projects. Bahuguna notably coined the slogan "Ecology is permanent economy," emphasizing the intrinsic link between environmental health and sustainable livelihoods. He spearheaded the anti-Tehri Dam movement for decades, embodying a steadfast commitment to protecting vulnerable communities and the fragile Himalayan ecosystem. His work significantly influenced conservation efforts and ecological awareness, inspiring subsequent environmental and social justice movements across India.

2. Early Life and Background

Sunderlal Bahuguna's early life in the Himalayan region profoundly shaped his dedication to social and environmental causes, laying the foundation for his lifelong activism rooted in Gandhian ideals.

2.1. Childhood and Education

Sunderlal Bahuguna was born on 9 January 1927, in the village of Maroda, near Tehri, in the Indian state of Uttarakhand. He claimed that his ancestors, bearing the surname Bandyopadhyaya, had migrated from Bengal to Tehri some 800 years prior. His formative years in the serene yet vulnerable Himalayan landscape instilled in him a deep connection to nature and an early awareness of social injustices.

2.2. Early Social Activism

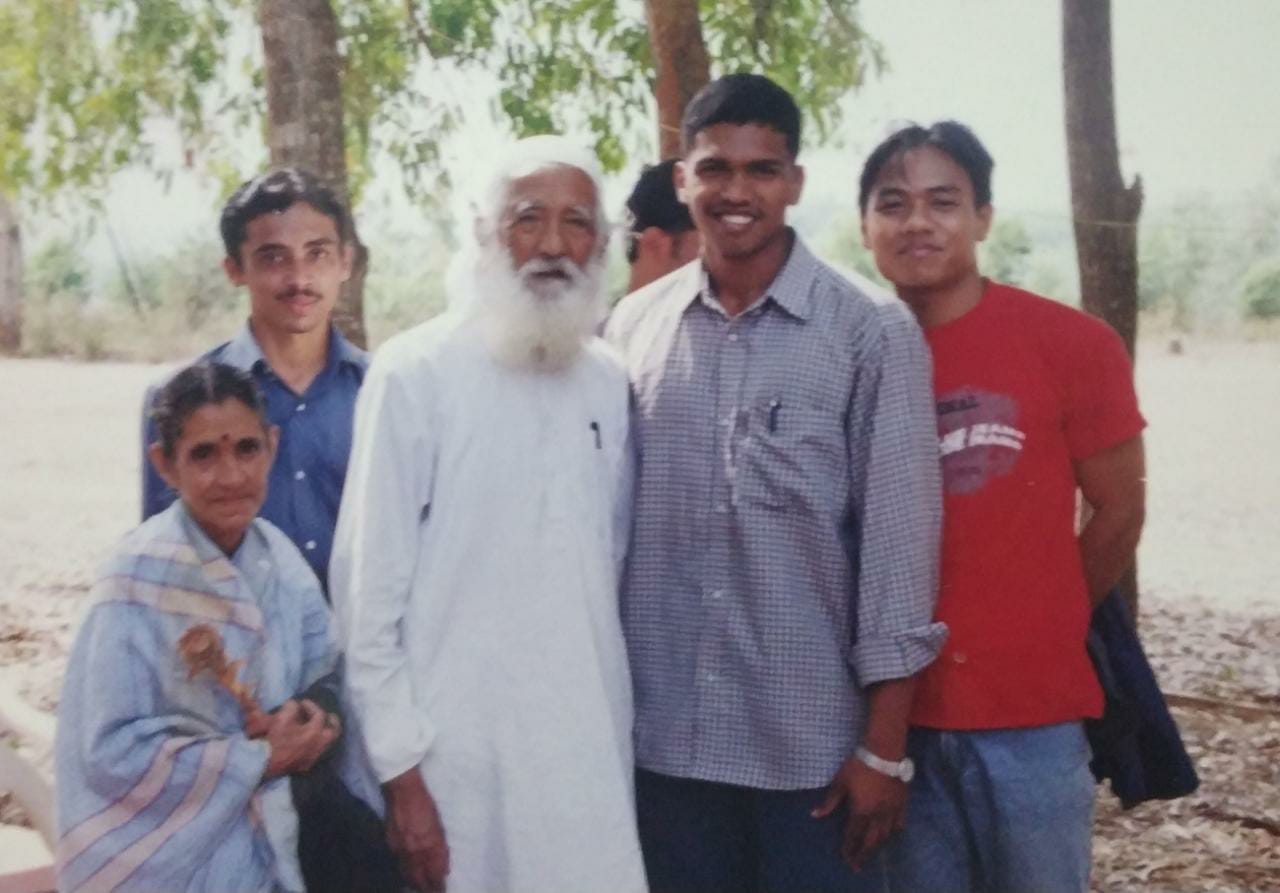

Bahuguna began his social activities at the young age of 13, under the guidance of Shri Dev Suman, a nationalist who propagated a message of non-violence. During the period leading up to India's Independence in 1947, Bahuguna actively mobilized people against colonial rule and was associated with the Indian National Congress in Uttar Pradesh. He dedicated himself to combating social ills, notably fighting against untouchability and leading anti-liquor drives among hill women from 1965 to 1970. His early experiences and the influence of Gandhi inspired him to adopt Gandhian principles as the guiding philosophy for his life and activism. He married his wife, Vimla Bahuguna, on the condition that they would live among rural communities and establish an ashram in a village, further cementing his commitment to grassroots social work. Inspired by Gandhi, he embarked on extensive walks through Himalayan forests and hills, covering more than 2.9 K mile (4.70 K km) on foot. These journeys allowed him to directly observe the extensive damage inflicted by large-scale developmental projects on the delicate Himalayan ecosystem and the subsequent degradation of social life in the villages.

3. Philosophy and Ideology

Sunderlal Bahuguna's life and activism were profoundly guided by the principles of Gandhian philosophy, particularly Ahimsa and Satyagraha. He adopted these core tenets as the bedrock of his approach to environmental and social justice. His commitment to non-violent resistance was evident throughout his major campaigns, where he consistently employed peaceful means, such as hunger strikes and marches, to advocate for his causes. Bahuguna believed that true progress could only be achieved through a harmonious relationship between humanity and nature, encapsulated in his enduring slogan, "Ecology is permanent economy." This philosophy underscored his conviction that ecological preservation was not merely an environmental concern but a fundamental economic necessity for the long-term well-being and sustainability of communities, especially those dependent on natural resources. His ideology championed the rights of local communities, particularly the vulnerable, to protect their traditional livelihoods and environments from destructive development.

4. Major Campaigns and Activism

Sunderlal Bahuguna dedicated his life to environmental and social causes, leading and participating in several significant campaigns that left a lasting impact on India's conservation and social justice landscape.

4.1. Chipko Movement

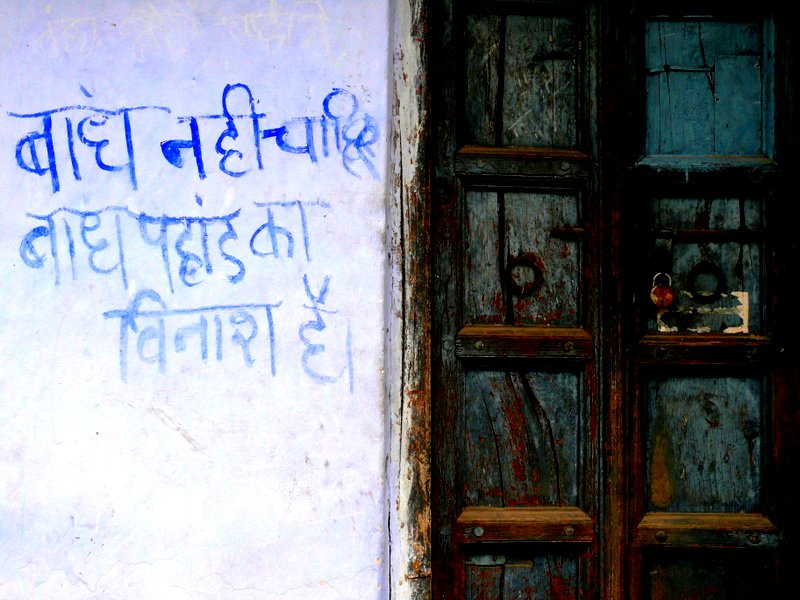

The Chipko movement emerged in the early 1970s in Uttarakhand (then part of Uttar Pradesh) as a spontaneous grassroots effort by villagers to protect their forests from commercial logging. The idea for the movement was notably suggested by Sunderlal Bahuguna and his wife, Vimla Bahuguna. The name "Chipko" literally means "to cling" in Hindi, reflecting the primary tactic of the movement where people would hug trees to prevent lumbermen from felling them. Sunderlal Bahuguna became a pivotal leader of this movement, playing a crucial role in bringing it to national and international prominence. One of his most significant contributions was coining the powerful slogan, "Ecology is permanent economy," which succinctly articulated the movement's core philosophy: that the long-term health of the environment is indispensable for sustainable economic well-being.

To garner widespread support and raise awareness, Bahuguna undertook an arduous 3.1 K mile (5.00 K km) trans-Himalaya march from 1981 to 1983, traveling from village to village to mobilize communities. His tireless efforts culminated in a crucial meeting with the then-Prime Minister of India, Indira Gandhi. This meeting is widely credited with influencing Gandhi's subsequent decision in 1980 to impose a 15-year ban on the felling of green trees in the Himalayan region, a landmark policy achievement for the movement. Bahuguna also worked closely with Gaura Devi, another pioneer of the Chipko movement, strengthening its collective impact.

4.2. Anti-Tehri Dam Protests

Sunderlal Bahuguna was a central figure in the decades-long campaign against the construction of the Tehri Dam on the Bhagirathi River in the Himalayas. He staunchly opposed the dam due to its potential ecological devastation and the displacement of thousands of local residents. Bahuguna employed Satyagraha methods, including repeated and prolonged hunger strikes on the banks of the Bhagirathi, as a powerful form of non-violent protest.

In 1995, he ended a 45-day hunger strike after receiving an assurance from the then-Prime Minister P. V. Narasimha Rao that a review committee would be appointed to assess the dam's ecological impacts. Undeterred, he undertook another significant fast, lasting 74 days, at Gandhi Samadhi, Raj Ghat, during the tenure of Prime Minister H. D. Deve Gowda, who personally committed to a project review. Despite his persistent efforts and a court case that spanned over a decade in the Supreme Court, construction on the Tehri project resumed in 2001, leading to Bahuguna's arrest on 24 April 2001. The dam reservoir began filling in 2004, and on 31 July 2004, Bahuguna was finally evacuated to new accommodation in Koti. He later relocated to Dehradun, the capital city of Uttarakhand, where he lived with his wife.

4.3. Social and Community Work

Beyond his prominent environmental campaigns, Sunderlal Bahuguna was deeply committed to improving the social and economic conditions of the Himalayan communities. He tirelessly worked to uplift the livelihoods and rights of the hill people, with a particular focus on empowering working women. Bahuguna was also actively involved in temperance movements, advocating for liquor prohibition to address social issues within communities. Furthermore, his early activism included struggles against casteist discrimination, demonstrating his broader commitment to social welfare and justice for all.

5. Legacy and Influence

Sunderlal Bahuguna's activism left an indelible mark on environmentalism and social justice movements, both within India and globally. His work served as a powerful inspiration for subsequent grassroots efforts aimed at conservation and community empowerment.

One notable example is the Appiko movement, which started on 8 September 1983, in Karnataka. Led by environmental activist Pandurang Hegde, the Appiko movement (meaning "to hug" in Kannada, mirroring Chipko) protested against the felling of trees, monoculture, and deforestation in the Western Ghats. This movement directly drew inspiration from Bahuguna and the Chipko movement. Bahuguna himself had visited the region in 1979 to support the campaign against the proposed Bedthi hydroelectric project. Following the inception of the Appiko movement, Bahuguna and Pandurang Hegde collaboratively walked across various parts of South India, actively promoting ecological conservation, with a special emphasis on protecting the Western Ghats, a globally recognized biodiversity hotspot. Their combined efforts, along with the broader Save the Western Ghats Movement, led to a significant moratorium on green felling across the region in 1989.

Bahuguna is widely recognized as a passionate defender of the Himalayan people and India's vital rivers. His holistic approach, integrating environmental protection with social equity, profoundly influenced conservation efforts and raised ecological awareness. His advocacy underscored the interconnectedness of human well-being and environmental health, inspiring countless individuals and organizations to adopt similar principles in their pursuit of a more sustainable and just world.

6. Awards and Recognition

Sunderlal Bahuguna received numerous awards and honors throughout his life, recognizing his profound contributions to environmental conservation and social work.

- 1981: He was offered the Padma Shri, one of India's highest civilian honors, but he famously refused to accept it. His refusal was a principled stand against the government's decision to proceed with the Tehri Dam project, despite his sustained protests and advocacy.

- 1986: He was awarded the Jamnalal Bajaj Award for his constructive work, acknowledging his significant contributions to social development.

- 1987: The Right Livelihood Award was bestowed upon the Chipko movement, recognizing its innovative and effective approach to environmental protection. As a key leader, Bahuguna was a central figure in this recognition.

- 1989: The IIT Roorkee conferred upon him an Honorary Degree of Doctor of Social Sciences, in recognition of his impactful social and environmental contributions.

- 2009: He received the Padma Vibhushan, India's second-highest civilian award, from the Government of India for his lifelong dedication to environment conservation. This award marked a significant acknowledgment of his enduring legacy.

7. Writings and Publications

Sunderlal Bahuguna authored and co-authored several books and articles, articulating his vision for environmental sustainability, social equity, and the importance of ecological balance. His writings serve as important resources for understanding his philosophy and the movements he championed.

- Sundar Lal Bahuguna Sankalp ke Himalaya (सुन्दर लाल बहुगुणा संकल्प के हिमालयHindi) (2013), edited and published by his daughter, Madhu Pathak. This book provides insights into his life and work, and helps readers understand ecological mass-movements in the Garhwal Himalayan region.

- India's Environment: Myth & Reality, co-authored with Vandana Shiva and Medha Patkar.

- Environmental Crisis and Humans at Risk: Priorities for action, co-authored with Rajiv K. Sinha.

- Bhu Prayog Men Buniyadi Parivartan Ki Or (भू प्रयोग में बुनियादी परिवर्तन की ओरHindi) (Hindi).

- Dharti Ki Pukar (धरती की पुकारHindi) (Hindi).

- Ecology is Permanent Economy: The Activism and Environmentalism of Sunderlal Bahuguna (2013) by George Alfred James, a comprehensive study of Bahuguna's activism and environmental philosophy.

8. Personal Life

Sunderlal Bahuguna's personal life was intrinsically linked to his activism and philosophical commitments. He married Vimla Bahuguna, and their union was founded on a shared commitment to live among rural communities and establish an ashram in a village. This decision underscored his dedication to grassroots engagement and a life rooted in the realities of the people he sought to serve.

9. Death and Tributes

Sunderlal Bahuguna passed away on 21 May 2021, at the age of 94, due to complications from COVID-19. He had tested positive for the virus on 8 May 2021, and was admitted for treatment. His passing marked the end of an era for environmental activism in India.

Following his death, numerous tributes poured in from across India and beyond, honoring his life and enduring legacy. The Indian dairy cooperative Amul commemorated him in one of its widely recognized advertisements, reflecting his significant cultural impact. On 21 May 2022, a year after his passing, his daughter, Madhu Pathak, edited and published a souvenir book dedicated to his life and work. This book featured contributions from esteemed social activists, writers, intellectuals, and politicians, further detailing Bahuguna's life and providing insights into the ecological mass-movements within the Garhwal Himalayan region. His ashes were later immersed in the roots of plants in Sundarban, symbolizing his deep connection to nature.

10. Assessment and Critical Evaluation

Sunderlal Bahuguna's contributions to environmentalism and social justice are widely regarded as monumental. His leadership in the Chipko movement not only brought global attention to the importance of forest conservation but also empowered local communities, particularly women, to protect their natural resources. His powerful slogan, "Ecology is permanent economy," became a guiding principle for sustainable development, emphasizing that environmental health is not separate from economic well-being but foundational to it. His decades-long, non-violent resistance against the Tehri Dam exemplified his unwavering commitment to the fragile Himalayan ecosystem and the rights of displaced communities, even in the face of immense governmental pressure.

Bahuguna's adherence to Gandhian principles of non-violence and Satyagraha provided a moral compass for his campaigns, inspiring a generation of activists. His efforts extended beyond environmental protection to include vital social work, such as fighting against untouchability and promoting temperance, demonstrating a holistic approach to community welfare. While his campaigns, particularly against the Tehri Dam, faced opposition and ultimately did not prevent the dam's construction, his persistent advocacy ensured that environmental and social impacts became central to the discourse surrounding large-scale development projects in India. His legacy continues to inspire grassroots movements like the Appiko movement and remains a testament to the power of individual conviction in driving collective action for ecological balance and social equity.