1. Overview

Shuzo Ohira (大平修三Ōhira ShūzōJapanese, 1930-1998) was a prominent Japanese professional Go player, renowned for his aggressive and powerful playing style. Born in Gifu Prefecture, Japan, Ohira began learning Go at the age of nine under the guidance of his father and quickly advanced, becoming an uchideshi (live-in apprentice) to the legendary Kitani Minoru. He achieved professional 1-dan in 1947 and reached the pinnacle rank of 9-dan by 1963.

Ohira's career was marked by significant achievements, including an impressive four consecutive victories in the Nihon Ki-in Championship and a win in the Hayago Championship. His distinctive approach to the game earned him nicknames such as "Hammer Punch" and "Killer" due to his relentless attacks and ability to dismantle opponent's large groups of stones. Despite battling chronic health issues in his later years, he continued to play professionally, leaving a lasting legacy as a formidable and influential figure in the world of Go. He was considered a representative player of the generation born in the early Showa era.

2. Life and Career

Shuzo Ohira's life and professional Go career spanned over five decades, marked by dedication, formidable skill, and significant contributions to the game.

2.1. Early Life and Go Training

Shuzo Ohira was born on March 16, 1930, in Gifu, Gifu Prefecture, Japan. His introduction to Go came at the age of nine, guided by his father, Kenji Ohira, who was a professional Go player himself (5-dan) who had transitioned from being an elementary school teacher. Shuzo received what was described as a "Sparta education" in Go from his father, which instilled in him a strong foundation.

At the age of ten, in 1941, Ohira received a Go lesson from the legendary Kitani Minoru 9-dan in Gifu, playing on a seven-stone handicap. The following year, he played against Kitani again, this time with a three-stone handicap. These encounters led to him becoming an uchideshi (live-in apprentice) under Kitani Minoru, and he moved to Hiratsuka, where Kitani's famous dojo was located. However, due to his weak physical constitution, he temporarily returned to his hometown. In early 1945, he returned to Hiratsuka and became an insei (a trainee professional player) at the Nihon Ki-in. Shortly after, due to frequent air raids during World War II, he returned to Gifu, where he remained until the end of the war. Afterward, he assisted Yasuo Sakai in Nagoya before making his professional debut.

2.2. Early Professional Career

Ohira's professional career began in 1947 when he was promoted to professional 1-dan at the Nihon Ki-in Tokai Hombu (the predecessor of the Chubu General Hombu). He swiftly advanced, achieving 2-dan in the same year. In 1949, he reached 4-dan and began participating in the Oteai (professional qualification matches) at the Tokyo Hombu of the Nihon Ki-in. However, he faced a temporary setback, being demoted to 2-dan. He persevered, regaining his 4-dan rank in 1951 and subsequently settled in Tokyo.

In 1952, Ohira was the runner-up in the Youth Players Championship. The following year, 1953, proved to be a pivotal one as he won the Youth Players Championship, married, and was promoted to 5-dan. During this period, he, along with Yoshinori Kano and Katsuji Kada, was recognized as one of the "Post-war New Three Stars," symbolizing the emerging talent in the Go world. He continued to rise through the ranks, reaching 6-dan by 1955. In 1957, he was the runner-up in the Prime Minister's Cup. He participated in the Saikoi League in 1958, although he was demoted after a record of two wins, five losses, and one jigo (draw). By 1960, he had reached 8-dan and won the Prime Minister's Cup. His ascent culminated in 1963 when he achieved the highest professional rank of 9-dan.

2.3. Peak Period and Major Achievements

Ohira's most successful period began in the mid-1960s. In both 1964 and 1965, he challenged Sakata Eio in the Nihon Ki-in #1 Player Deciding Match, gaining valuable experience despite being defeated in both attempts. His breakthrough came in 1966 when he challenged and defeated Sakata Eio, 3-1, to capture the Nihon Ki-in Championship. He then went on to defend this title for four consecutive years, defeating formidable opponents such as Rin Kaiho, Toshiro Yamabe, and Hidehiro Miyashita. This impressive feat earned him the moniker "Championship Man" (選手権男Senshuken OtokoJapanese). His title match against Rin Kaiho in 1967 was particularly notable as it was the first title match between two players born in the Showa era.

During his winning streak, Ohira endured physical challenges, defending his title against Yamabe while suffering from chronic otitis media and gout. Yamabe, who had once called Ohira "the reincarnation of Jowa" for his powerful style, praised him at this time for developing "not only strength but also brightness." In 1970, he lost the Nihon Ki-in Championship title to Yoshio Ishida, but he successfully reclaimed it in 1972 by defeating Ishida in a rematch.

Ohira was a consistent participant in the top professional leagues, playing in the Meijin League for five terms and the Honinbo League for four terms, demonstrating his sustained presence among the elite. In 1967, during the Nissei Gonin Nuki Knockout Tournament (Nissei Hayago Series), he notably defeated Sakata Eio after Sakata had eliminated eight consecutive opponents, bringing the tournament to an end. In 1977, Ohira won his first major title, the Hayago Championship. He re-entered the Meijin League in 1984 and 1988. In 1987, he set a new record for successive wins with 17 consecutive victories. His later notable achievements include being the runner-up in the IBM Cup in 1990 and reaching the Best 4 in the Kisei Strongest Player Deciding Match in 1992.

2.4. Playing Style and Philosophy

Shuzo Ohira was celebrated for his unique and aggressive playing style, often described as powerful and direct. He was known for his "Hammer Punch" (ハンマーパンチHanmā PanchiJapanese), a nickname given to him by Maeda Chinun, reflecting his tendency to launch devastating attacks. It was often said that "stones targeted by Ohira do not survive," indicating his skill in decisively eliminating opponent's groups. He was also dubbed "Killer" even before Masao Kato gained a similar reputation, emphasizing his merciless approach to attacking.

Despite his fearsome reputation for aggressive play, Ohira himself stated that he deeply respected classical Go masters like Honinbo Shuei. He described his preferred style as "extending and pulling back" (伸びて引く碁nobite hiku goJapanese), asserting that his intention was not simply to capture stones but to develop his position and then strike with precision. A famous example of his power was the 1973 Nihon Ki-in Championship Game 2, where he famously captured a massive 40-point group belonging to challenger Sakata Eio. His style was also characterized by a strong emphasis on the "sides" of the board.

Ohira provided a self-assessment of his strengths and weaknesses: he held a "secret confidence" in his ability in mid-game fighting, believing he was second to none. However, he admitted that his "opening game sense was considerably naive," suggesting that his early board development was not his strongest suit. This self-awareness highlights his strategic approach to leveraging his strengths in the crucial middle stages of a game.

2.5. Personal Life and Later Years

Beyond his professional career, Shuzo Ohira was known for his kind and gentle personality, which earned him the affectionate nickname "Good Person Prototype" (善人原器Zennin GenkiJapanese). He was considered a representative Go player of the "Showa Hitoketa" generation, referring to those born in the first decade of the Showa era (1926-1935).

His personal interests included movies, supporting the Chunichi Dragons baseball team, and admiring the works of Japanese historical novelist Eiji Yoshikawa.

In his later life, Ohira faced significant health challenges. In 1996, he underwent surgery for an aortic aneurysm, which necessitated a period of absence from professional play from April to September. Despite this, he made a successful return to the Go board. The following year, in 1997, he required a second aortic aneurysm surgery, leading to another period of recovery from April to October before he again resumed playing. Shuzo Ohira resided in Yokohama, Japan, before his passing on December 11, 1998, at the age of 68, due to a myocardial infarction. His dedication to Go remained unwavering even in the face of serious illness. His overall professional record stands at 800 wins, 456 losses, and 5 jigo.

3. Titles and Records

Shuzo Ohira's career was marked by numerous significant titles, runner-up finishes, and notable statistical achievements, solidifying his status as one of Japan's top Go players.

3.1. Titles Held

Ohira secured several prestigious titles throughout his professional career:

- Youth Players Championship: 1953

- Prime Minister's Cup: 1960

- Nihon Ki-in Championship: 1966, 1967, 1968, 1969, 1972 (held for four consecutive years from 1966)

- Hayago Championship: 1977

3.2. Other Achievements and Runner-up Finishes

Beyond his titles, Ohira's consistent performance in various tournaments and leagues is evident in his runner-up finishes and strong league participation:

- Youth Players Championship: Runner-up 1952

- Prime Minister's Cup: Runner-up 1957

- Nihon Ki-in #1 Player Deciding Match: Challenger 1964, 1965, 1968

- Hayago Championship: Runner-up 1970, 1969 (as per English source)

- Tengen: Runner-up 1976

- NHK Cup: Runner-up 1978

- IBM Hayago Open: Runner-up 1990

- Kisei 9-dan Tournament: Winner 1988, 1991

- Pro Top Ten Tournament: 9th place 1974, 10th place 1975

- Meijin League: 5 terms

- Honinbo League: 4 terms

Ohira also participated in international competitions:

- Sino-Japanese Go Exchange:

- 1984: 0-2 against Liu Xiaoguang

- 1988: 1-0 against Fang Tianfeng (方天豊Fāng TiānfēngChinese)

- Sino-Japanese Super Go:

- 1987: 1-1 (won against Liu Xiaoguang, lost against Wang Qun (王群Wáng QúnChinese))

- 1989: 0-1 (lost against Zhang Wendong (張文東Zhāng WéndōngChinese))

3.3. Awards and Special Records

Ohira's contributions and performance were recognized with several awards and notable statistical records:

- Kido Award:

- Technique Award: 1972, 1975, 1984, 1987

- Highest Winning Percentage Award: 1975 (17 wins, 6 losses, 73.9%), 1987 (31 wins, 6 losses, 83.8%)

- Consecutive Wins Award: 1987 (17 consecutive wins)

- Career Total: 800 wins, 456 losses, 5 jigo (draws).

4. Representative Game

The fourth game of the 13th Nihon Ki-in Championship challenge match between defending champion Sakata Eio and challenger Shuzo Ohira, played on January 26-27, 1966, stands as a prime example of Ohira's tenacity and strategic prowess. This game secured Ohira his first major title, overcoming the dominant Sakata.

Ohira had reached this challenge match for the third time, having previously overcome strong opponents like Kaoru Iwamoto, Yoshiro Miwa, Masao Sugiuchi, Hosai Fujisawa, and Hideo Otake in the preliminary tournament. Despite losing his previous two challenges against Sakata in the Nihon Ki-in #1 Player Deciding Match in 1964 and 1965, Ohira felt he was gaining ground, stating, "After the good fight in the #1 Player Deciding Match, I felt that no matter who the opponent was, I wouldn't lose so easily." Sakata, though having lost the Meijin title to Rin Kaiho the previous year, was still a leading figure, holding the Honinbo title for five consecutive terms and having won the Nihon Ki-in Championship seven times, followed by two consecutive defenses. Sakata won the first game of the five-game series but also commented, "I have a bad feeling this time." Ohira, playing Black in the second game, countered Sakata's attack, and Sakata's mistake in handling a ko threat allowed Ohira to win and even the score. Ohira then won the third game, taking the lead.

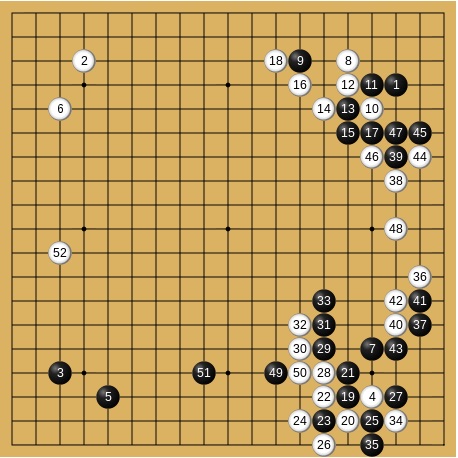

The fourth game, with Ohira playing Black, began with his favored tasuki-komoku (diagonal corner star point) opening. However, Black's choice of joseki (standard opening sequence) in the upper right corner, specifically Black 9's one-space jump, was poor, leading to White building a strong thickness that harmonized well with White's tight formation in the upper left. Black expanded on the right side from the joseki in the lower right, but White's moves 34 and 36 were sharp, and White 48 settled the right side, giving White an advantage.

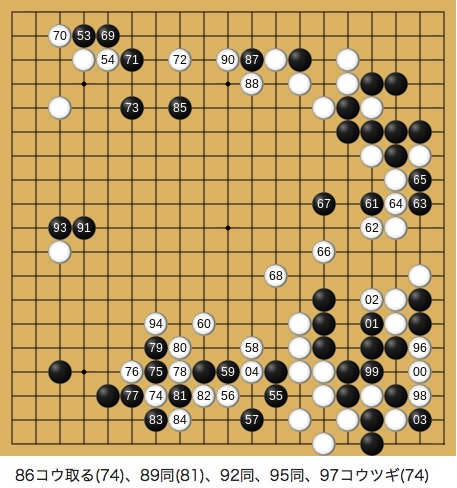

Sensing a disadvantage, Black 51 aimed to attack White's lower right group, and Black 61 further sought to link up and attack. However, White 66 and 68 were good defensive moves, allowing White to skillfully handle the precarious position and avoid Black's attempts to cut. Black temporarily played large points from 59 to 73, but White 74 was a sharp invasion. White 84's atari would have led to a severe loss if Black had connected immediately. However, Black 85 prepared for a difficult ko fight, as connecting immediately at 104 to create a ko would have allowed White to use Black's upper side stones as ko threats. White made a ko threat at Black 91, and then White 94 enlarged the ko. Ultimately, Black could not answer White 96's ko threat, leading to an exchange where Black's lower right was traded for White's group.

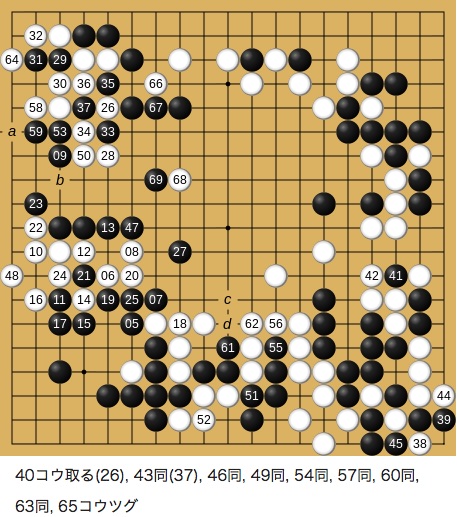

Although White maintained an advantage, the difference in territory began to narrow. Black 119 in the battle on the left side was a mistake, allowing White to take sente (initiative) and play at 126, expanding White's advantage. White 128 (one line above Black 133 in the actual game) would have secured the win. However, Black 133 initiated a desperate ko fight. If White 148 had resolved the ko, exchanging White's left side for Black's upper side would have led to a White win. White 164, played after Black 153's cut, was a critical error. Had White played at White 'a', followed by Black 'b', White's ko capture, and then Black 'c' and White 'd' to force Black into a disadvantageous ko, White would have won. In the actual game, this led to a close half-point game with Black having a thick position. The lead then widened, and the game concluded after 264 moves with Black winning by three and a half points. Ohira's victory in this fierce and hard-fought match marked his first major title, achieving success in his third attempt at a championship.

5. Works

Shuzo Ohira authored several books on Go, sharing his insights and knowledge with enthusiasts and aspiring players. His publications include:

- Large Patterns Focus (大模様の焦点Ōmoyo no ShōtenJapanese) - Go Super Books 19, Nihon Ki-in, 1971

- Appreciating Famous Games (名局鑑賞室Meikyoku KanshōshitsuJapanese) - Go Super Books 28, Nihon Ki-in, 1974 (republished as Meikyoku Kanshōshitsu: Nihon Ki-in Archive - Go of the Edo Period from Dōsaku to Shūsaku, Nihon Ki-in, 2010)

- Dōseki/Meijin Inseki (道的・名人因碩Dōseki Meijin InsekiJapanese) - Nihon Igo Taikei 4, Chikuma Shobō, 1976

- Powerful Arm Shuzo Ohira (怪腕 大平修三Kaiwan Ōhira ShūzōJapanese) - Gei no Tankyū Series 2, Nihon Ki-in, 1977

- Shuzo Ohira (大平修三Ōhira ShūzōJapanese) - Gendai Igo Taikei 30, Kodansha, 1983

- Ohira Tsumego 120 Problems (大平詰碁120題Ōhira Tsumego 120 DaiJapanese), Kinen-sha, 1978

- Side Invasions (辺の打ちこみHen no UchikomiJapanese) - Uro Books, Nihon Ki-in, 1989

6. Assessment and Legacy

Shuzo Ohira left an indelible mark on the world of Go, primarily through his distinctive and powerful playing style. He was widely recognized for his aggressive approach to the game, earning nicknames like "Hammer Punch" and "Killer" for his ability to target and decisively eliminate large enemy groups, often surprising opponents with his sheer force. This reputation for strength was balanced by his personal character, which was described as genial and earning him the moniker "Good Person Prototype."

His career spanned several decades, and he was a prominent figure among the generation of players born in the early Showa era. Ohira's success in major tournaments, including his remarkable four consecutive wins in the Nihon Ki-in Championship, solidified his standing as an elite player. He consistently participated in the top professional leagues, proving his sustained skill at the highest levels of the game.

Beyond his direct competitive achievements, Ohira's influence extended through his published works, where he shared his unique perspectives on Go strategy and famous games. His self-awareness regarding his strengths in mid-game fighting and weaknesses in the opening phase provided valuable insight into his strategic mindset. Despite battling serious health issues in his later years, his unwavering dedication to Go until his passing further cemented his legacy as a true master of the game. Ohira's powerful yet principled approach to Go continues to be remembered and studied by future generations of players.