1. Overview

Shah Jahan's reign marked a period of immense prosperity and artistic flourishing for the Mughal Empire, particularly in architecture. However, it also saw a shift in religious policy compared to his predecessors and faced significant internal challenges, including a devastating famine and a bitter war of succession among his sons that ultimately led to his imprisonment.

2. Early Life and Background

Shah Jahan's early life was shaped by his lineage, education, and the complex political landscape of the Mughal court, which prepared him for his future role as emperor.

2.1. Birth and Family

Born on 5 January 1592 in Lahore, then part of the Mughal Empire (present-day Pakistan), he was the ninth child and third son of Prince Salim, who would later ascend the throne as Jahangir. His mother was Jagat Gosain, a Rathore Rajput Princess from Marwar. His paternal grandparents were Emperor Akbar and Mariam-uz-Zamani, while his maternal grandparents were Raja Udai Singh Sahib Bahadur and Rani Manrang Deviji Sahiba. The name Khurram (خرمPersian, lit. "joyous") was chosen by his grandfather, Emperor Akbar, with whom he shared a close bond. Jahangir noted Akbar's fondness for Khurram, stating that Akbar considered him his "true son."

At birth, Akbar, believing Khurram to be auspicious, insisted that the prince be raised in his own household rather than Salim's. Thus, Khurram was entrusted to the care of Ruqaiya Sultan Begum, one of Akbar's wives, who raised him affectionately. Jahangir's memoirs record Ruqaiya's profound love for Khurram, stating she loved him "a thousand times more than if he had been her own." After Akbar's death in 1605, Khurram returned to the care of his birth mother, Jagat Gosain, to whom he became deeply devoted, addressing her as Hazrat in court chronicles. When Jagat Gosain died in Agra (Akbarabad) on 8 April 1619, Shah Jahan was inconsolable, mourning for 21 days, abstaining from public meetings, and consuming only vegetarian meals. His consort, Mumtaz Mahal, supervised food distribution to the poor and offered spiritual comfort during this period.

2.2. Childhood and Education

Khurram received a comprehensive education befitting a Mughal prince, which included extensive martial training and exposure to diverse cultural arts, such as Persian poetry and music. Much of this education was overseen by his father, Jahangir. While he showed little interest in studying Turki as a child, he was attracted to Hindi literature, with his Hindi letters even being mentioned in Jahangir's biography, Tuzk-e-Jahangiri.

In 1605, as Emperor Akbar lay on his deathbed, a 13-year-old Khurram remained steadfastly by his side, refusing to leave despite his mother's attempts to persuade him. This was a politically unstable time, and Khurram was at considerable physical risk from his father's political adversaries. He was eventually ordered to return to his quarters by senior imperial women, including Salima Sultan Begum and his grandmother Mariam-uz-Zamani, as Akbar's health deteriorated.

2.3. Early Military Campaigns

Prince Khurram demonstrated exceptional military prowess from a young age. His first major military test came during the Mughal campaign against the Rajput state of Mewar, which had been hostile to the Mughals since Akbar's reign. After a year of intense war of attrition, Rana Amar Singh I of Mewar conditionally surrendered to the Mughal forces, making Mewar a vassal state of the Mughal Empire. In 1615, Khurram presented Kunwar Karan Singh, Amar Singh's heir, to Jahangir and was subsequently honored. His military rank (mansab) steadily increased, rising from 12000/6000 to 15000/7000, then to 20000/10000 by 1616, an honor equal to his brother Parvez.

In 1616, upon his departure for the Deccan, Jahangir bestowed upon him the title Shah Sultan Khurram. In 1617, Khurram was tasked with subduing the Lodhi nobles in the Deccan to secure the Empire's southern borders and restore imperial control. His success in these campaigns earned him immense prestige. Upon his return in 1617, he performed koronush before Jahangir, who embraced him and granted him the illustrious title of Shah Jahan (شاه جهانPersian, "King of the World"). Jahangir further elevated his military rank to 30000/20000 and allowed him the unprecedented honor of a special throne in his Durbar. In 1618, Shah Jahan received the first copy of Tuzk-e-Jahangiri from his father, who considered him "the first of all my sons in everything."

2.4. Court Politics and Rebellion

Mughal succession was not based on primogeniture, but on princely sons competing for military success and court power, often leading to rebellions. After his father crushed a rebellion by his half-brother Khusrau Mirza in 1605, Khurram initially remained distant from court intrigues. As the third son, he avoided challenging the major power blocs, allowing him to build his own support base. Jahangir entrusted Khurram with guarding the palace and treasury during the pursuit of Khusrau and later ordered him to bring his grandmother Mariam-uz-Zamani and Jahangir's harem. Khurram's vigilance also uncovered a plot during Khusrau's second rebellion, earning him praise from his father. Jahangir even had Khurram weighed against gold and silver at his mansion, a mark of great favor.

Over time, Khurram grew closer to his father and was increasingly considered the de facto heir-apparent, a status formalized in 1608 when Jahangir granted him the sarkar of Hissar-e-Feroza, traditionally reserved for the heir. However, following her marriage to Jahangir in 1611, Nur Jahan, a Persian noblewoman, gradually amassed immense power, becoming the de facto ruler as Jahangir indulged in wine and opium. Her relatives gained influential positions, forming what historians call the Nur Jahan junta.

Khurram was in constant conflict with his stepmother, who favored her son-in-law Shahryar Mirza for succession. Nur Jahan tried to weaken Khurram's position by sending him on distant campaigns in the Deccan while favoring Shahryar. Sensing a threat to his status, Khurram rebelled against Jahangir in 1622. When the Persians besieged Kandahar, Nur Jahan ordered Khurram to march there, but he refused, fearing she would poison his father against him and promote Shahryar in his absence. Kandahar was lost to the Persians after a 45-day siege due to Khurram's refusal.

Khurram raised an army and marched against his father and Nur Jahan, but was defeated at Bilochpura in March 1623. He took refuge in Udaipur with Maharana Karan Singh II, staying first in Delwada Ki Haveli and then in Jagmandir Palace, whose mosaic work is believed to have inspired the Taj Mahal. In November 1623, he found asylum in Bengal Subah after being driven from Agra and the Deccan. He defeated and killed the Subahdar of Bengal, Ibrahim Khan Fath-i-Jang, at Akbarnagar on 20 April 1624, seizing a large treasury including elephants, horses, and 4.00 M INR in specie in Dhaka. After a brief stay, he moved to Patna. His rebellion ultimately failed, and he was forced to submit unconditionally after his defeat near Allahabad. Though forgiven in 1626, underlying tensions with Nur Jahan persisted.

3. Accession to the Throne

The death of Emperor Jahangir initiated a fierce power struggle among his sons, which Shah Jahan navigated with strategic alliances and decisive actions to secure his claim to the Mughal throne.

3.1. Succession Crisis

Upon Jahangir's death in 1627, the wazir Asaf Khan, who was Khurram's father-in-law and a long-time supporter, acted swiftly and forcefully to thwart Nur Jahan's plans to place her son-in-law, Shahryar, on the throne. Asaf Khan immediately placed Nur Jahan under house arrest and secured control of Khurram's three sons who were under her charge. He orchestrated court intrigues, including the temporary enthronement of Dawar Bakhsh (Khusrau's son) as a puppet emperor to buy time for Khurram's arrival and prevent Shahryar from gaining an advantage. Meanwhile, Shahryar had declared himself emperor in Lahore but was quickly defeated and arrested by Asaf Khan's forces.

3.2. Coronation and Consolidation of Power

Upon receiving news in the Deccan, Khurram ordered Asaf Khan to capture and execute other rival princes, including Dawar Bakhsh, his brother Garshasp, and his cousins Tahmuras and Hoshang (sons of the late Prince Daniyal Mirza). These executions took place on 23 January 1628. On 24 January 1628, Khurram entered Agra, claiming the title "Shah Jahan," meaning "King of the World," a name reflecting his ambition and pride in his Timurid ancestry.

On 14 February 1628, Shah Jahan held his grand coronation ceremony in Agra, which was celebrated for its opulence. European visitors of the time referred to him as "the Magnificent." He took the full regnal name ابو المظفر شہاب الدین محمد صاحب قران ثانی شاہ جہاں بادشاہ غازیAbu ud-Muzaffar Shihab ud-Din Mohammad Sahib ud-Quiran ud-Thani Shah Jahan Padshah GhaziUrdu. He rewarded those who facilitated his ascension, appointing Asaf Khan as his chief minister (vizier) and granting Mahabat Khan the title of خانِ خاناںKhan-i-KhananUrdu ("Highest of Khans"). Nur Jahan was stripped of her imperial status and privileges, placed under house arrest, and lived a quiet life until her death. With his rivals eliminated, Shah Jahan was able to rule his empire without contention, firmly consolidating his power.

4. Reign (1628-1658)

Shah Jahan's reign saw significant administrative developments, ambitious military campaigns, a notable shift in social and religious policies, and an unparalleled patronage of arts and architecture, leading to a period often called the "Golden Age" of the Mughal Empire.

During Shah Jahan's rule, the Mughal Empire became a formidable military power. By 1648, the army comprised 911,400 infantry, musketeers, and artillery personnel, alongside 185,000 سوارsowarPersian (cavalry) commanded by princes and nobles. This period also witnessed an appropriation of his Timurid heritage, manifested in initiatives like the Timurid Renaissance, aimed at building historical and political bonds with his ancestral roots, though his Central Asian military campaigns were largely unsuccessful. The Marwari horse breed was introduced and became Shah Jahan's favorite, and Mughal cannons were mass-produced at the Jaigarh Fort. The number of nobles and their contingents increased nearly fourfold, leading to higher demands for revenue. However, his financial and commercial policies generally ensured stability, centralizing administration and systematizing court affairs.

India during his reign was a rich hub for arts, crafts, and architecture, attracting some of the world's finest architects, artisans, craftsmen, painters, and writers. According to economist Angus Maddison, Mughal India's share of global gross domestic product (GDP) grew from 22.7% in 1600 to 24.4% in 1700, surpassing China to become the world's largest economy. Despite the vast expenditures on military campaigns and construction, the empire maintained a substantial reserve, including 95.00 M INR in accumulated funds, half in coins and half in jewels.

4.1. Administration and Economy

Shah Jahan's reign saw the empire operate as a vast military machine, leading to a significant increase in the number of nobles. The empire's territory expanded, and its revenue doubled compared to Akbar's era, fueled by both territorial growth and improved agricultural production. By the 1640s, the number of nobles had doubled to 443. The top 73 nobles managed 37% of the empire's revenue, while Shah Jahan's four sons managed 8.2%. About 20% of the upper nobility were Hindus, including 73 Rajputs and 10 Marathas, indicating successful territorial expansion in the Deccan.

Shah Jahan ended the concept of "imperial devotees" (from Akbar's دین الهیDin-i IlahiPersian) and instead promoted the idea of "descendants of the emperor." Nobles would offer gifts to the emperor upon the birth of their sons and seek imperial names for them. This fostered loyalty, military prowess, Persian etiquette, and artistic knowledge among the nobility.

4.2. Military Campaigns and Territorial Expansion

The Mughal Empire experienced moderate territorial expansion during Shah Jahan's reign, with his sons leading armies on various fronts. While expanding into the Deccan, the empire faced challenges in the northwest and against European powers.

4.2.1. Deccan Sultanates

Shah Jahan launched successful campaigns to consolidate Mughal control over the Deccan. He focused on the remaining Deccan sultanates, which had been weakened by his father's previous campaigns. In 1632, Mughal forces captured the fortress of Daulatabad in Maharashtra, effectively ending the Nizam Shahi dynasty by imprisoning its last ruler, Husein Shah of Ahmednagar. This marked the annexation of Ahmednagar's northern territories into the Mughal Empire, while its southern parts were divided between Bijapur and Golconda.

In 1635, Golconda formally submitted to Mughal authority, followed by Bijapur in 1636. Both sultanates recognized Mughal suzerainty, striking coins and conducting Friday prayers in the emperor's name. After these successes, Shah Jahan appointed his third son, Aurangzeb, as the Viceroy of the Deccan, comprising the regions of Khandesh, Berar, Telangana, and Daulatabad. During his viceroyalty, Aurangzeb conquered Baglana, defeating its Raja, Baharji. Baglana, a small Maratha kingdom, was strategically important as it controlled the main route from Surat and the western ports to Burhanpur in the Deccan. Although it had historically been subservient to Muslim rulers, Shah Jahan decided on its complete annexation in 1637. Baharji died shortly after the conquest, and his son converted to Islam, receiving the title of Daulatmand Khan. Aurangzeb continued his military successes in the Deccan, defeating Golconda in 1656 and Bijapur in 1657. The increasing inclusion of Maratha figures within the imperial nobility indicated the success of Mughal expansion in the Deccan.

4.2.2. Northwest Frontier and Central Asia

The northwest frontier proved more challenging for Mughal expansion. Shah Jahan aimed to reclaim Samarkand, the ancestral seat of the Timurids, an ambition that proved costly and ultimately unsuccessful. The Khanate of Bukhara, under the Janid dynasty (successor to the Shaybanids), became a point of contention. Although initially amicable, relations soured as the Janids attacked Kabul.

In 1646, Shah Jahan dispatched his son, Murad Bakhsh, to lead an invasion of Central Asia targeting Balkh and Badakhshan. With an army of 75,000, Murad Bakhsh and later Aurangzeb temporarily occupied these territories. However, strong resistance from the Uzbeks and the barrenness of the land forced a retreat in 1647, leading to Balkh and Badakhshan reverting to Bukharan control. The Mughals were only able to extend their territory a few kilometers north of Kabul.

4.2.3. Wars with Safavids

Kandahar, a major city in Afghanistan, was a long-standing disputed territory between the Mughal and Safavid empires. Although it had been under Safavid control since 1622, the Safavid governor of Kandahar, Ali Mardan Khan, defected to the Mughal side in 1637, bringing Kandahar back into the Mughal Empire.

However, the Safavids retaliated. Seeing an opportunity during the Mughal conflicts with the Uzbeks, Abbas II recaptured Kandahar in 1649. Despite repeated sieges by Mughal armies under Aurangzeb (in 1649 and 1652) and Dara Shikoh (in 1653) during the Mughal-Safavid War (1649-1653), Kandahar remained unconquered by the Mughals and was never regained. This marked a significant setback for Shah Jahan's expansionist ambitions in the northwest.

Shah Jahan also maintained diplomatic relations with the Ottoman Empire. In 1637, he sent an embassy led by Mir Zarif to Sultan Murad IV, then encamped in Baghdad, proposing an alliance against Safavid Persia. The Sultan received the envoys warmly, exchanging lavish gifts. A return embassy from the Ottomans, led by Arsalan Agha, reached Shah Jahan in June 1640. Although gifts were exchanged, Shah Jahan found Sultan Murad's return letter discourteous. Murad IV's successor, Sultan Ibrahim, later sent another letter encouraging war against the Persians, but no reply from Shah Jahan is recorded.

4.2.4. Conflict with the Portuguese

Shah Jahan's reign also witnessed direct military action against European trading powers. In 1631, he ordered Qasim Khan, the Mughal viceroy of Bengal, to expel the Portuguese from their fortified trading post at Port Hooghly. The Portuguese settlement was well-defended with cannons, warships, and robust walls.

The Mughals accused the Portuguese of trafficking, particularly the abduction of peasants, and also viewed them as commercial rivals, as their presence contributed to the decline of the Mughal-controlled port of Saptagram. Shah Jahan was especially incensed by the activities of the Jesuits in the region. On 25 September 1632, the Mughal Army launched a successful siege, gaining control over the Bandel region, and the garrison was punished.

On 23 December 1635, Shah Jahan issued a royal decree (farman) ordering the demolition of the Agra Church, occupied by Portuguese Jesuits. While he allowed Jesuits to conduct private religious ceremonies, he strictly prohibited them from preaching or converting Hindus and Muslims. Despite this, he also granted 777 bighas (a traditional land unit) of rent-free land to the Augustinian Fathers and the Christian community in Bandel, West Bengal, which shaped its Portuguese heritage for centuries.

4.2.5. Other Conflicts

Beyond the major campaigns, Shah Jahan also suppressed several internal uprisings. A significant rebellion was led by the Sikh leader, Guru Hargobind. In response, Shah Jahan ordered their destruction. However, Guru Hargobind's forces defeated the Mughal army in several key engagements, including the Battle of Amritsar, the Battle of Kartarpur, the Battle of Rohilla, and the Battle of Lahira.

The Kolis of Gujarat also rebelled against Mughal rule. In 1622, Shah Jahan sent Raja Vikramjit, the Governor of Gujarat, to subdue the Kolis in Ahmedabad. Between 1632 and 1635, four different viceroys were appointed to manage Koli activities, reflecting the persistent nature of the revolts. The Chunvalia Kolis of Kankrej in North Gujarat, led by one Kánji, were particularly notorious for plundering merchandise and committing highway robberies. Ázam Khán, a viceroy appointed to restore order, pursued Kánji, forcing his surrender and an annual tribute of 10.00 K INR. Ázam Khán also established two fortified posts, Ázamábád and Khalílábád, in Koli territory and forced the surrender of the Jam of Nawanagar. Subsequent viceroys, including Ísa Tarkhán (who implemented financial reforms), Aurangzeb (who engaged in religious disputes, notably demolishing a Jain temple in Ahmedabad before being replaced), Shaista Khan (who failed to subdue the Kolis), and finally Prince Murad Bakhsh (in 1654), worked to restore order and suppress the Koli rebels.

4.3. Social and Religious Policies

Shah Jahan's reign marked a notable shift from the more liberal and inclusive religious policies of his grandfather, Akbar, towards a more orthodox Islamic approach. This change was influenced by growing Islamic revivalism, particularly the Naqshbandi movement.

4.3.1. Religious Policies

Under Shah Jahan, the empire saw a move towards stricter adherence to Islamic law, with ulama increasingly advocating for strict شريعةshariaArabic application. This led to certain restrictions on non-Muslims. In 1632, Shah Jahan issued an order prohibiting the construction of new Hindu temples and the repair of old ones. As a result, 76 Hindu temples in Varanasi were reportedly destroyed. He also imposed restrictions on the construction and renovation of Christian churches.

The treatment of captured Portuguese Christians from Hooghly exemplified this shift. After their capture, 300 Christians were brought to Agra, where they were coerced to convert to Islam; those who refused were executed. Contemporary accounts suggest captured women and girls were confined to harems, while older women were given to أميرamirsArabic (nobles). The Christian church in Lahore was also demolished around this time. However, Shah Jahan himself celebrated Islamic festivals and dispatched nine embassies to Mecca and Medina. Despite these instances of religious intolerance, some historians suggest that religious conflict was largely contained beyond these incidents.

4.3.2. Famine and Rebellions

One of the most devastating events during Shah Jahan's reign was the Deccan famine of 1630-32, caused by three consecutive crop failures. The famine resulted in an estimated two million deaths due to starvation. Reports from the time describe dire conditions, including grocers selling dog meat and mixing powdered bones with flour, and even instances of parents resorting to cannibalism, consuming their own children. Entire villages were wiped out, with streets littered with corpses. In response to the crisis, Shah Jahan initiated لنگرlangarPersian (free kitchens) to provide relief to the famine victims.

In addition to the Sikh rebellion and Koli uprisings, Shah Jahan faced a major rebellion by the Afghan noble Khan Jahan Lodi in 1629. Khan Jahan, a former favorite of Jahangir and governor of a southern province, had fallen from favor due to perceived dishonorable military conduct and suspicious dealings with the Ahmednagar Sultanate. Suspected by the court, he was summoned to the imperial capital. In October 1629, Khan Jahan, along with his family and 2,000 followers, escaped the capital and rebelled. Shah Jahan sent a pursuing army, but Khan Jahan managed to evade them, reaching Daulatabad, the capital of the Ahmednagar Sultanate, where he was welcomed as a military commander. Despite hoping other Afghan nobles would join him, none did, as they respected Shah Jahan's authority. Khan Jahan eventually left Ahmednagar and fled to Punjab, but was captured and executed in February 1631. His head and that of his son were sent to Shah Jahan and displayed at the gates of Agra Fort, a grim customary warning to rebels.

4.4. Patronage of Arts and Architecture

Shah Jahan's reign is widely considered the golden age of Mughal architecture, marked by a prolific output of magnificent structures that demonstrated his profound artistic vision and the empire's vast wealth. He was one of the greatest patrons of Mughal architecture, using imperial resources to manifest his authority and aesthetic.

4.4.1. Architectural Achievements

His most iconic creation is the Taj Mahal in Agra, a legendary mausoleum built out of profound love for his wife, Mumtaz Mahal. Its construction began in 1632, took about 22 years to complete, and was finished around 1654. The Taj Mahal's design, which may have drawn inspiration from Ibrahim Adil Shah II's tomb (روضہ ابراہیمیIbrahim RauzaUrdu) in Bijapur, involved architects and craftsmen from across the Islamic world. It features a base measuring 187 ft (57 m) per side, a central dome 190 ft (58 m) high, and four 138 ft (42 m) tall minarets, all clad in white marble adorned with intricate inlay carvings. The structure, constructed from white marble over brick, involved 20 years of labor. Upon his death, Shah Jahan was interred beside Mumtaz Mahal in the Taj Mahal.

Other major constructions during his reign include:

- The Red Fort in Delhi, also known as the Delhi Fort or لال قلعہLal QilaUrdu (Red Fort). Commissioned in 1638 and completed in 1648, its walls extend for 1.6 mile (2.5 km) and vary in height from 52 ft (16 m) to 108 ft (33 m).

- Significant sections of the Agra Fort, adding to its grandeur.

- The Jama Masjid (Great Mosque) in Delhi, one of India's largest mosques.

- The Wazir Khan Mosque in Lahore, renowned for its intricate ornamentation.

- The Moti Masjid (Pearl Mosque) within the Agra Fort and another one in Lahore.

- The Shalimar Gardens in Lahore.

- Sections of the Lahore Fort.

- The Mahabat Khan Mosque in Peshawar.

- The Mini Qutub Minar in Hastsal.

- The Jahangir mausoleum, his father's tomb, whose construction was overseen by his stepmother Nur Jahan.

- The Shah Jahan Mosque in Thatta, Sindh province of Pakistan, built in 1647. This mosque is constructed with red bricks and blue glazed tiles, possibly imported from Hala. It boasts 93 domes, making it the world's largest mosque with such a number of domes, and is designed with impressive acoustics, allowing a person speaking at one end to be heard at the other if the speech exceeds 100 decibels. It has been on the tentative UNESCO World Heritage List since 1993.

Shah Jahan also commissioned the opulent Peacock Throne (تخت طاووسTakht-i TausPersian), created to celebrate his rule. Completed in 1635 after seven years of work, it was adorned with 8.60 M INR worth of jewels and 1.40 M INR worth of gold. The throne featured diamonds, rubies, sapphires, and emeralds, with a massive ruby from Abbas I (bearing the names of Timur, Shah Rukh, Ulugh Beg, and Abbas, alongside Akbar, Jahangir, and Shah Jahan himself) at its canopy's center. Shah Jahan also inscribed profound verses from the Quran on his architectural masterpieces, demonstrating a blend of artistry and piety. He also established a new capital, شاہجہان آبادShahjahanabadUrdu (present-day Old Delhi), where the Red Fort was located. This new city, which he entered in April 1648, housed 57,000 people within its royal palace, with an estimated 400,000 citizens residing in the 6.4 K acre (2.59 K ha) urban area outside the walls.

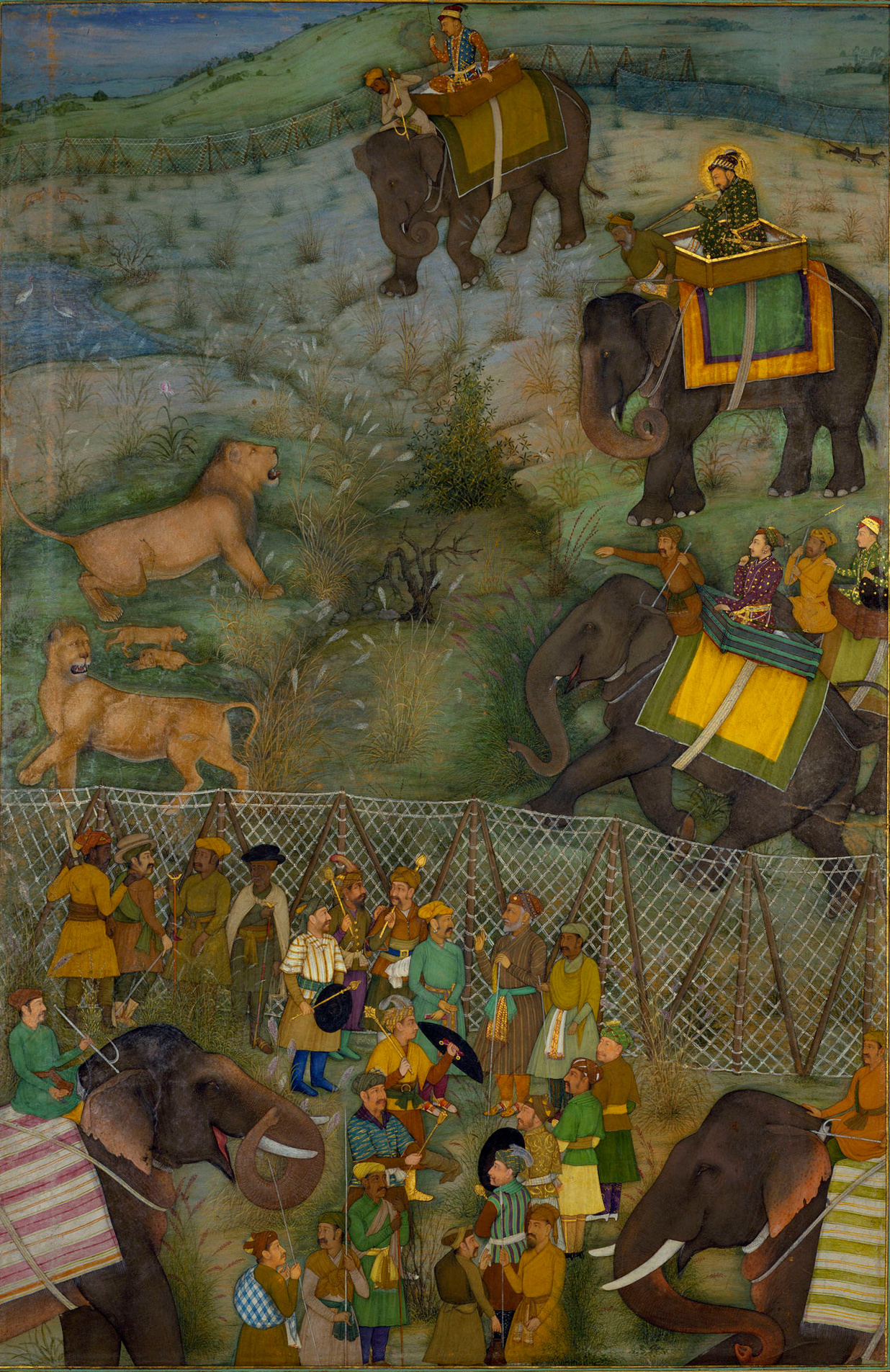

4.4.2. Arts, Literature, and Coinage

Shah Jahan's era was a period of flourishing for Mughal painting and poetry. He commissioned the پادشاهنامهPadshahnamaPersian, an illustrated chronicle of his achievements, in 1635. One volume of this work, depicting triumphant battles and court ceremonies, is preserved in the Royal Library at Windsor Castle. Shah Jahan also had a keen aesthetic sense for architecture and art, notably ordering 777 gardens in his favorite summer residence of Kashmir, some of which survive today.

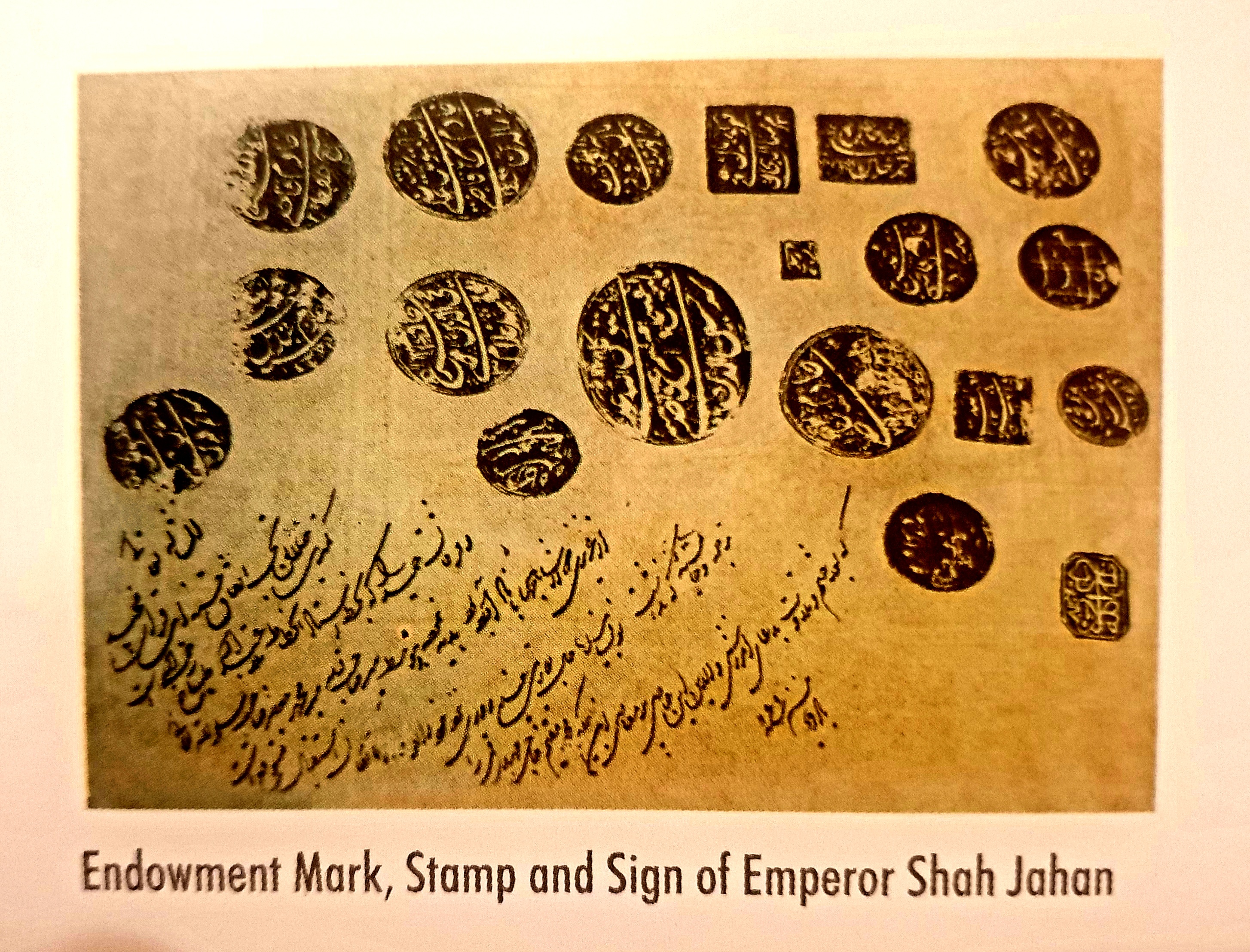

Shah Jahan continued the tradition of striking coins in three metals: gold (mohur), silver (rupee), and copper (dam). His coins issued before his accession bear the name Khurram. His coinage includes:

- Gold Mohur from Akbarabad (Agra)

- Silver rupee coins from Patna and Multan

- Copper Dam from Daryakot mint

- A silver rupee coin struck in Tatta, dated 1044 AH (1635 AD)

5. Personal Life

Shah Jahan's personal life was largely defined by his deep affection for Mumtaz Mahal and the numerous children they had, though his later years were also marked by rumors and increasing indulgence after her death.

5.1. Marriages and Children

In 1607, Khurram became engaged to Arjumand Banu Begum (1593-1631), who would later be known as Mumtaz Mahal (ممتاز محلPersian, lit. "The Exalted One of the Palace"). Their engagement lasted an unusually long five years, a duration chosen by court astrologers to ensure a happy marriage. They were married in 1612. Arjumand belonged to an influential Persian noble family; her father, Asaf Khan, served as Chief Minister, and her grandfather, Mirza Ghiyas Beg, was Jahangir's finance minister. Her aunt, Mehr-un-Nissa, became Empress Nur Jahan.

Before marrying Mumtaz Mahal, Shah Jahan first married a Persian princess, Kandahari Begum, in 1610, who was the daughter of a great-grandson of Ismail I, the founder of the Safavid dynasty. She bore his first child, Parhez Banu Begum. He also married Izz un-Nisa Begum, a Persian princess and daughter of Shahnawaz Khan, in 1617. During his rebellion against Jahangir, he also married his maternal half-cousin, Kunwari Leelavati Deiji, a Rathore Rajput Princess. Court chroniclers note that these subsequent marriages were primarily for political considerations, and these wives held only the status of royal consorts.

The marriage between Shah Jahan and Mumtaz Mahal was exceptionally happy, and he remained devoted to her. They had fourteen children together, seven of whom survived into adulthood.

| Name | Mother | Portrait | Lifespan | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Parhez Banu Begum | Kandahari Begum | 21 August 1611 - | Shah Jahan's first child, born to his first wife, Kandahari Begum. She was her mother's only child and died unmarried. | |

| Hur-ul-Nisa Begum | Mumtaz Mahal | 30 March 1613 - | The first of fourteen children born to Shah Jahan's second wife, Mumtaz Mahal. She died of smallpox at the age of 3. | |

| Jahanara Begum | Mumtaz Mahal | 23 March 1614 - | Shah Jahan's favorite and most influential daughter. Jahanara became the First Lady (Padshah Begum) of the Mughal Empire after her mother's death. She died unmarried. | |

| Dara Shikoh | Mumtaz Mahal | 20 March 1615 - | The eldest son and heir-apparent. He was favored as a successor by his father and elder sister, but was defeated and killed by his younger brother, Aurangzeb, in a struggle for the imperial throne. He married and had issue. | |

| Shah Shuja | Mumtaz Mahal | 23 June 1616 - | He survived the initial war of succession but was later killed. He married and had issue. | |

| Roshanara Begum | Mumtaz Mahal | 3 September 1617 - | She was influential among Shah Jahan's daughters and sided with Aurangzeb during the war of succession. She died unmarried. | |

| Aurangzeb | Mumtaz Mahal | 3 November 1618 - | Succeeded his father as the sixth Mughal emperor after winning the war of succession. | |

| Jahan Afroz | Izz-un-Nissa | 25 June 1619 - | The only child of Shah Jahan's third wife, Izz-un-Nissa (titled Akbarabadi Mahal). Jahan Afroz died at the age of one year and nine months. | |

| Izad Bakhsh | Mumtaz Mahal | 18 December 1619 - | Died in infancy. | |

| Surayya Banu Begum | Mumtaz Mahal | 10 June 1621 - | Died of smallpox at the age of 7. | |

| Unnamed son | Mumtaz Mahal | 1622 | Died soon after birth. | |

| Murad Bakhsh | Mumtaz Mahal | 8 October 1624 - | He was killed in 1661 on Aurangzeb's orders. He married and had issue. | |

| Lutf Allah | Mumtaz Mahal | 4 November 1626 - | Died at the age of one and a half years. | |

| Daulat Afza | Mumtaz Mahal | 8 May 1628 - | Died in infancy. | |

| Husnara Begum | Mumtaz Mahal | 23 April 1629 - | Died in infancy. | |

| Gauhara Begum | Mumtaz Mahal | 17 June 1631 - | Mumtaz Mahal died while giving birth to her on 17 June 1631 in Burhanpur. She died unmarried. |

Mumtaz Mahal was a politically astute woman who served as a crucial advisor and confidante to Shah Jahan. As empress, she wielded immense power, consulted on state matters, attended council meetings (شوریshuraPersian or دیوانdiwanPersian), and held responsibility for the imperial seal, allowing her to review official documents. Shah Jahan also granted her the right to issue her own orders (حكمhukumsArabic) and make appointments.

Mumtaz Mahal died at the young age of 38 on 7 June 1631, due to a postpartum haemorrhage after a painful 30-hour labor while giving birth to Princess Gauhar Ara Begum in Burhanpur, Deccan. Contemporary historians describe Shah Jahan as "paralysed by grief" and prone to weeping fits. His 17-year-old daughter, Jahanara, was so distressed that she distributed gems to the poor in hopes of divine intervention. Mumtaz Mahal's body was temporarily buried in Zainabad, a walled pleasure garden built by Shah Jahan's uncle, Prince Daniyal, along the Tapti River. Her death profoundly affected Shah Jahan and inspired the construction of the magnificent Taj Mahal, where she was later reburied. Shah Jahan's grief was so profound that his beard, which previously had only about 20 white hairs, turned completely white. He did not engage in state affairs for a week and reportedly wore white clothes instead of colorful ones, avoiding music. His passion for politics also seemed to diminish.

5.2. Relationship with Jahanara Begum

After Shah Jahan fell ill in 1658, his eldest daughter, Jahanara Begum, assumed significant influence in the Mughal administration. This proximity led to several historical accusations and rumors of an incestuous relationship between Shah Jahan and Jahanara. Contemporary European travelers like François Bernier, Joannes de Laet, Peter Mundy, and Jean-Baptiste Tavernier mentioned these rumors circulating in the Mughal court.

However, modern historians, including K. S. Lal and Niccolao Manucci (who was a contemporary of Bernier), largely dismiss these accusations as mere gossip or "the talk of the low people," asserting that no credible witness ever corroborated such claims. Manucci argued that Jahanara's devoted care for her father during his illness might have led to such insinuations by the general populace. Historian K. S. Lal suggests that the rumors were potentially propagated by courtiers and مولاناmullahsArabic (Islamic scholars), possibly fueled by political motivations. Given that Emperor Aurangzeb imprisoned Jahanara with Shah Jahan in Agra Fort and given the existing animosity between Dara Shikoh and Aurangzeb (with Jahanara supporting Dara), it is plausible that Aurangzeb sought to tarnish the reputations of both his father and half-sister to solidify his own claim to the throne.

6. Illness, War of Succession, and Imprisonment

The final phase of Shah Jahan's reign was marked by a serious illness that triggered a devastating war of succession among his sons, ultimately leading to his deposition and long imprisonment.

6.1. Illness and Succession Crisis

In September 1657, Shah Jahan became seriously ill in Delhi, hovering between life and death for over a week. Some accounts suggest his illness was exacerbated by his indulgence in sensual pleasures and aphrodisiacs after Mumtaz Mahal's death, which had continued for over two decades. During his illness, his eldest son, Dara Shikoh (Mumtaz Mahal's favorite son), assumed the role of regent. This act immediately ignited animosity among his younger brothers, who viewed it as a direct challenge to their claims to the throne, even though Shah Jahan eventually recovered.

The news of Shah Jahan's severe illness, rumored to be fatal, quickly spread across the empire, prematurely triggering a full-blown war of succession among his four sons while he was still alive.

6.2. War of Succession

The second son, Shah Shuja, the Viceroy of Bengal, was the first to act, declaring his independence and minting coins in his name in November 1657. He then marched towards Delhi. The fourth son, Murad Bakhsh, the Viceroy of Gujarat, also declared independence, amassed wealth from plundering the Surat fortress, and marched towards Delhi.

Aurangzeb, the third son and Viceroy of the Deccan, was more cautious, waiting until his position was strong. He allied with Murad Bakhsh, promising him Punjab, Kashmir, Sindh, and Afghanistan if they won. Shah Jahan, despite recovering, realized the situation had escalated beyond his control. He agreed to commit all state forces to Dara Shikoh and ordered all generals to obey him. However, despite Dara's military advantages (fresh troops, more cannons), few predicted his victory, as he lacked command ability and was unpopular among soldiers. His most powerful general, Jai Singh, was still marching with Suleiman Shikoh's army. Both Dara's advisors and Shah Jahan urged him to wait for Suleiman Shikoh's forces and choose a favorable defensive position, but Dara refused. Shah Jahan even offered to personally lead the army, which Dara also declined. Before Dara's departure from Agra, Shah Jahan tearfully warned him: "Well, Dara, if you wish to proceed as you have decided, then go. May God's blessings be upon you. But remember this short word: if you lose the battle, be careful not to appear before me again."

On 15 April 1658, Dara Shikoh's army clashed with the combined forces of Aurangzeb and Murad Bakhsh near Ujjain at the Battle of Dharmatpur. Although Dara's forces initially held an advantage, Murad Bakhsh's ferocity and the betrayal of Qasim Khan led to Dara's defeat.

Days after the Battle of Samugarh on 8 June 1658, where Dara's forces were routed by Aurangzeb and Murad Bakhsh near Agra, Dara fled towards Agra but, remembering his father's harsh words, did not meet him. Shah Jahan attempted to encourage Dara to join Suleiman Shikoh and provided resources, but Suleiman's army dissolved, preventing their reunion.

Aurangzeb and Murad Bakhsh entered Agra within days of the Battle of Samugarh. Aurangzeb sent conciliatory messages to Shah Jahan, feigning devotion and claiming to act only under his father's direction. Shah Jahan, wary of Aurangzeb's growing ambition, did not trust him. Aurangzeb repeatedly postponed a meeting with his father, fearing he might be captured, especially with Jahanara Begum by Shah Jahan's side. Instead, Aurangzeb sent his eldest son, Muhammad Sultan, to Agra Fort. Sultan forcefully expelled the guards and occupied the fort walls with his large contingent. Shah Jahan tried to test Sultan's loyalty, offering him the crown and promising kingship if he served him faithfully, but Sultan, fearing capture himself, conveyed he was acting on Aurangzeb's orders.

On 22 June, Itibar Khan, the new commander of Agra Fort appointed by Aurangzeb, confined Shah Jahan and the royal women, including Jahanara Begum, to the inner quarters of the fort, blocking access to many gates. Shah Jahan was forbidden from communicating with anyone and leaving his quarters without permission. Aurangzeb then wrote a letter to his father, sarcastically stating that Shah Jahan's supposed affection for Aurangzeb was belied by sending 2 elephants laden with gold rupees to Dara Shikoh to help him regroup. Aurangzeb claimed to have intercepted several letters from Shah Jahan to Dara.

After consolidating his position in Agra and securing the imperial treasury and gunpowder reserves, Aurangzeb left Shaista Khan in charge of Agra and set off with Murad Bakhsh in pursuit of Dara Shikoh. However, Aurangzeb soon betrayed Murad Bakhsh, capturing him during a banquet at Mathura and executing him in December 1661 after a supposed escape attempt. Aurangzeb absorbed Murad Bakhsh's army into his own. On 31 July 1658, Aurangzeb held his coronation in Delhi, proclaiming himself emperor and adopting the regnal name عالمگیرAlamgirPersian (meaning "World Seizer"), a title perhaps reflecting his triumph over Shah Jahan, the "King of the World."

6.3. Imprisonment in Agra Fort

Following the Battle of Samugarh in July 1658, despite Shah Jahan's full recovery from his illness, Aurangzeb declared him incompetent to rule. He placed his father under strict house arrest in Agra Fort, where he remained confined from July 1658 until his death in January 1666.

Shah Jahan's eldest surviving daughter, Jahanara Begum Sahib, voluntarily chose to share his 8-year confinement, diligently nursing him in his old age. During his imprisonment, Shah Jahan never met Aurangzeb again, though they exchanged letters. However, Aurangzeb's letters were often filled with complaints about his father's perceived favoritism towards Dara Shikoh, reflecting a resentful and imperious tone. Shah Jahan also faced financial constraints during his confinement; Aurangzeb seized his personal jewels, leaving him struggling even for minor expenses like repairing his violin or acquiring proper slippers. Despite these hardships, Shah Jahan was not entirely isolated, spending his final years surrounded by royal women, particularly his devoted daughter Jahanara Begum.

7. Death and Burial

Shah Jahan's final years were spent in confinement, contemplating his legacy, culminating in his death and burial beside his beloved wife in the Taj Mahal.

7.1. Final Years

Shah Jahan lived in confinement in Agra Fort from 1658 until his death. During these years, he gazed upon the Taj Mahal from his chambers, a constant reminder of his deep love for Mumtaz Mahal and his greatest architectural achievement. Although he never met Aurangzeb after his deposition, they maintained correspondence. These letters often contained Aurangzeb's resentful expressions of dissatisfaction regarding his father's past favoritism toward Dara Shikoh. Shah Jahan also endured financial difficulties, with Aurangzeb seizing his personal jewels, forcing him to struggle for funds even for necessities. Despite these indignities, Shah Jahan was not lonely; he was attended by royal women, most notably his eldest daughter, Jahanara Begum, who cared for him devotedly.

7.2. Death and Funeral

In January 1666, Shah Jahan's health declined due to a recurrence of the illness he had suffered during the succession war. Confined to his bed, he progressively weakened. On 22 January 1666, at the age of 74, Shah Jahan passed away. Before his death, he commended the ladies of the imperial court, particularly his consort of later years, Akbarabadi Mahal, to Jahanara's care. His final moments involved reciting the شهادةShahadaArabic (Laa ilaaha ill allah) and verses from the Quran.

His chaplain, Sayyid Muhammad Qanauji, and Kazi Qurban of Agra oversaw the preparation of his body. It was moved to a nearby hall, washed, enshrouded, and placed in a sandalwood coffin. Princess Jahanara had planned a grand state funeral, complete with a procession led by eminent nobles and citizens scattering coins for the poor. However, Aurangzeb, perhaps to assert his authority and prevent any public display of sympathy for the deposed emperor, refused such ostentation.

7.3. Burial

Instead, Shah Jahan's body was simply taken to the Taj Mahal by boat, a common practice for royalty whose bodies were not allowed to pass through city gates. He was laid to rest in the crypt beside his beloved wife, Mumtaz Mahal, fulfilling the purpose of the magnificent mausoleum he had built for her.

8. Legacy and Historical Evaluation

Shah Jahan's reign is remembered as a golden age of Mughal culture and architecture, but also for its significant social and religious shifts and the profound human cost of imperial ambitions.

8.1. Architectural Legacy

Shah Jahan left an unparalleled architectural legacy, marking his reign as the golden age of Mughal architecture. His personal ownership of the royal treasury and precious stones like the Koh-i-Noor diamond allowed him to invest enormously in grand constructions. The meticulous design and execution of these buildings, involving architects from around the world, resulted in structures that continue to stand as testaments to his vision. The Taj Mahal, built as a monument of love, is his most celebrated work and a UNESCO World Heritage Site, embodying both artistic perfection and deep personal sentiment.

Beyond the Taj Mahal, his contributions include the majestic Red Fort and Jama Masjid in Delhi, the elegant Naulakha Pavilion and Wazir Khan Mosque in Lahore, and the Moti Masjid in Agra Fort, among many others. These structures showcased a distinct architectural style characterized by symmetry, white marble, intricate inlay work, and calligraphic inscriptions. His work profoundly influenced subsequent architectural styles in India and remains a cornerstone of world heritage.

8.2. Socio-political Impact

Shah Jahan's reign also had a significant socio-political impact. While the empire experienced general stability and economic prosperity, as evidenced by its growing share of global GDP, his administrative centralization and systematization of court affairs were accompanied by increased demands for revenue due to the expanding military machine and the proliferation of nobles.

A critical aspect of his socio-political legacy was the shift in religious policy. Departing from Akbar's liberal approach, Shah Jahan's embrace of Islamic revivalist movements like the Naqshbandi order led to policies that were less tolerant towards non-Muslims. This included restrictions on temple construction, the demolition of some Hindu temples and Christian churches, and instances of forced conversion, which marked a departure from previous Mughal religious syncretism.

8.3. Criticism and Controversies

Despite the architectural and cultural splendor, Shah Jahan's reign faced criticism and controversy. His religious policies, particularly the destruction of Hindu temples and the forced conversion of Christians, have been viewed negatively by historians as a departure from the more tolerant policies of his grandfather.

The immense cost of his architectural ambitions and military campaigns, while a source of glory, also placed considerable economic strain on the empire, leading to increased taxes and potentially contributing to the devastating Deccan famine of 1630-32. The human cost of his ambitions was high, as seen in the lives lost during the famine and the suppression of rebellions. The legend that he ordered the hands of the Taj Mahal's builders to be cut off, while lacking evidence, reflects a popular perception of the extreme measures associated with his grand projects. His ruthless consolidation of power, marked by the execution of his brothers and nephews, also highlights a darker side to his rule.

8.4. Influence on Later Periods

Shah Jahan's reign and its distinctive architectural style profoundly influenced subsequent Mughal rulers. The grandeur and scale of his constructions set a new benchmark for imperial patronage, inspiring his successors, including Aurangzeb, despite their ideological differences. The centralized administrative system he refined and the large, well-organized military he commanded continued to be a template for the empire. However, the religious policies initiated during his time also set a precedent that intensified under Aurangzeb, contributing to future internal strife and ultimately impacting the empire's long-term stability. The architectural marvels, particularly the Taj Mahal, became enduring symbols of the Mughal Empire's power and artistic prowess, inspiring architects and artists for centuries.