1. Family Background and Early Life

Sakanoue no Tamuramaro's early life was deeply rooted in a family renowned for its martial heritage, which played a significant role in shaping his future career as a prominent military and political figure. This section delves into his ancestry, childhood, and initial steps in public service.

1.1. Ancestry and Clan

The Sakanoue clan, to which Tamuramaro belonged, claimed Han Chinese ancestry, specifically tracing their lineage back to Emperor Ling of Han through his great-grandson, Achino Omi. According to the Shoku Nihongi, an official historical record, Tamuramaro was a 14th-generation descendant of Emperor Ling. Further research suggests connections to the Asian mainland, possibly through immigrants from Baekje, a kingdom in ancient Korea. Despite these distinguished origins, the Sakanoue clan was considered a relatively local powerful family or lower-ranking official family before Tamuramaro's era. Nevertheless, the clan had a long-standing tradition as specialists in military arts, particularly horse archery, serving as guards for the imperial court across several reigns. His great-grandfather, Sakanoue no Ōkuni, served as a military official, and his grandfather, Sakanoue no Inukai, was praised for his martial talent from a young age and favored by Emperor Shōmu. Tamuramaro's father, Sakanoue no Karitamaro, was also granted the treatment of a court noble due to his martial skills. This generational dedication to military excellence established the Sakanoue clan as a "military family" renowned for its exceptional martial arts, and Tamuramaro and his siblings were educated from a young age to excel in these disciplines.

The lack of extensive detail on Sakanoue no Tamuramaro's life has led to a number of theories regarding aspects of his life. One popular theory, particularly spread among some black communities in Canada and the United States in the 1910s by anthropologists like Alexander Francis Chamberlain, suggested that Tamuramaro was of African origin. Other theories propose he was of Emishi origin or born in the Ōshū region, and there are various legends regarding Sakanoue no Tamuramaro, including a Tamura story.

1.2. Birth and Childhood

Sakanoue no Tamuramaro was born in 758, though his exact birthplace remains unclear. Some scholars speculate that if his name was derived from a place, then "Tamura-no-sato" in Heijō-kyō (present-day Nara) could be a strong candidate, based on the example of Ōtomo no Sukunamaro's daughter, Tamura no Ōiratsume, who was named after the village where her father resided. He was the second or third son of Sakanoue no Karitamaro. His mother's identity is not definitively known, though some scholars suggest a connection to the Unehimi clan through his sister, Sakanoue no Mataji.

In 770, when Tamuramaro was around 13 years old, his father Karitamaro was appointed Mutsu Chinjufu Shogun (Mutsu Provincial Governor and Commander of the Garrison) for about six months following his role in denouncing the machinations of Dōkyō during the Usa Hachiman-gū Oracle Incident. It is possible that young Tamuramaro accompanied his father to Taga Castle in Mutsu Province, spending part of his childhood in the relatively peaceful period just before the Thirty-Eight Years' War with the Emishi. In 772, his father Karitamaro also successfully petitioned the court to restore the position of district chief (gunji) in Takaichi District, Yamato Province, to the Hinoe clan, who were distant relatives of the Sakanoue clan.

1.3. Early Career

By 778, at the age of 21, Tamuramaro was eligible for appointment under the On'i no sei system, which granted official ranks based on a father's rank. As his father held the rank of Junior Fourth Rank, Lower Grade, Tamuramaro would have been granted Junior Seventh Rank, Upper Grade, if he were a common child, or Senior Seventh Rank, Lower Grade, if he were the eldest son of the principal wife. Regardless, he began his public service at the seventh rank. In 780, at 23, Tamuramaro was appointed Konoe Shōgen (Junior Military Official of the Inner Palace Guards), marking his entry into the military bureaucracy, consistent with his clan's martial tradition.

In 781, Emperor Kōnin abdicated in favor of Emperor Kanmu, whose mother, Takano no Niigasa, was descended from King Muryeong of Baekje. This imperial shift led to preferential treatment for immigrant clans, including the Sakanoue clan. In 782, his father Karitamaro was temporarily dismissed for alleged involvement in the Hyōkami Kawatsugu Incident but was reinstated just four months later. In 785, Karitamaro successfully petitioned to change the clan's name from Imiki to Sukune, with the main Sakanoue line becoming Ōsukune, signifying their elevated status. Later that year, at 28, Tamuramaro was promoted from Senior Sixth Rank, Upper Grade, to Junior Fifth Rank, Lower Grade, a significant advancement as it bypassed the intermediate "external" Fifth Rank, indicating the Sakanoue clan's rise from local magnates to central aristocracy. After his father's death in 786, Tamuramaro observed a year of mourning. He returned to service in 787, gaining additional appointments such as Takumi no Suke (Assistant Director of the Bureau of Carpentry) and Konoe Shōshō (Junior Captain of the Inner Palace Guards). By 790, he had been promoted to Echigo no Kami (Governor of Echigo Province).

2. Character and Personality

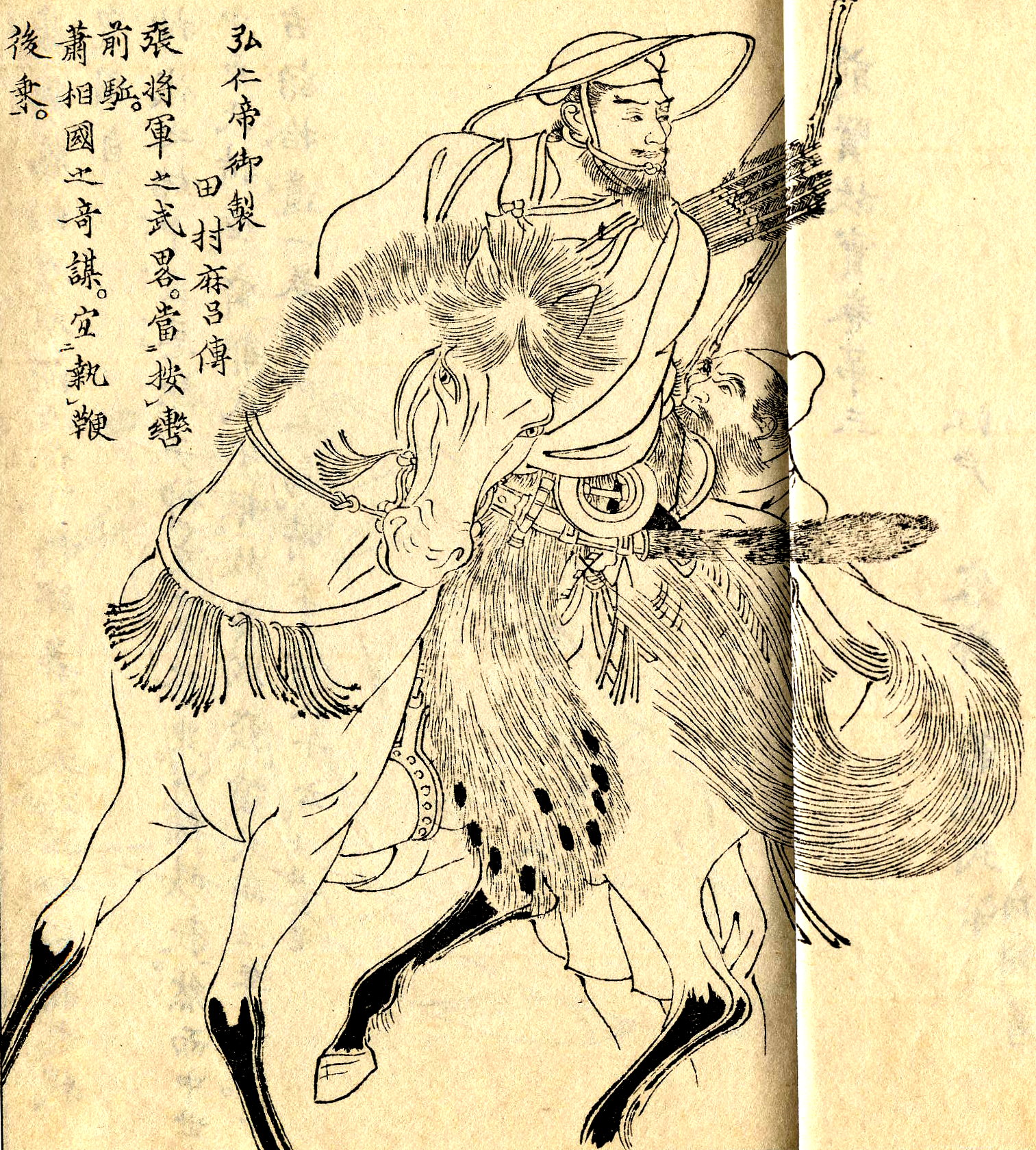

Sakanoue no Tamuramaro was revered for his exceptional character and innate martial abilities, which are detailed in historical accounts and biographical records like the Tamura Maro Denki and his death obituary in the Nihon Kōki. This section explores his physical appearance, disposition, and renowned military acumen.

2.1. Appearance and Disposition

Historical accounts describe Tamuramaro as a man of imposing physical presence. He was said to be 5 in (approximately 176 cm) tall with a chest 1 in (approximately 36 cm) thick. When standing face to face, he appeared to lean back, and from behind, he seemed to be bowing, indicating his substantial build. His eyes were described as sharp as a hawk's blue gaze, and his sideburns shone like spun gold. Despite his powerful physique, he was remarkably agile, capable of moving swiftly, akin to carrying a weight of 201 kin (approximately 120 kg) or as lightly as 64 kin (approximately 38 kg). His bearing was consistently rational and composed. He was also noted for his intense demeanor; when angered, his glare was said to be so fierce that it could instantly fell a wild beast, yet when he smiled and relaxed his brow, even a child would immediately feel at ease in his presence. This blend of formidable strength and gentle demeanor spoke to his profound integrity and approachable nature.

His disposition was characterized by deep sincerity and high moral standards. Records state that his true feelings were evident on his face, and his "peach blossoms were always red, even out of season," symbolizing his unwavering honesty. He was described as possessing an "innate firmness of will, like a pine tree whose color remains eternally green, even in winter," highlighting his unwavering resolve and noble character.

2.2. Martial Prowess and Strategy

Tamuramaro's military genius was widely acknowledged, with contemporary assessments hailing him as a "general by birth" (将種, shōshu). He was credited with devising strategies from the main camp that secured victories "a thousand miles away," demonstrating his exceptional foresight and tactical acumen. His military skills were lauded, stating that he learned military tactics from China, possessed the strategic brilliance of General Zhang Liang of Han, and the extraordinary ingenuity of Prime Minister Xiao He. These descriptions underscore his reputation as a master strategist and a formidable warrior, capable of commanding large forces and orchestrating complex campaigns with remarkable success.

3. Major Achievements and Activities

Sakanoue no Tamuramaro's career was marked by significant military campaigns and political advancements that shaped the early Heian period. This section outlines his military expeditions against the Emishi, key construction projects, and his rise in the political hierarchy.

3.1. Emishi Expeditions

The period saw escalating conflicts with the Emishi, indigenous people inhabiting the northern parts of Honshū. In 789, a large imperial army led by Kii no Kosami suffered a major defeat against Emishi forces under their leader, Aterui. These ongoing struggles highlighted the need for decisive military action.

3.1.1. First Emishi Expedition (Enryaku 13)

Preparations for the second Emishi campaign of the Kanmu era began in early 790. In 791, Sakanoue no Tamuramaro, along with Kudara no Konikishi Shuntetsu, was dispatched to the Tōkaidō provinces to inspect soldiers and their equipment for the upcoming expedition. The total troop strength for the campaign was around 100,000 men. On July 13, 791, Ōtomo no Otomaro was appointed Sei-tō Taishi (Commander-in-Chief of the Expeditionary Force to the East), and Tamuramaro was named one of the four Vice-Generals, alongside Kudara no Konikishi Shuntetsu, Tajhihi no Hamamari, and Kose no Otaru. The unusual number of junior officers (58 sergeants for a total of 100,000 troops) suggests a deliberate strategy to include many combat unit commanders. Although Tamuramaro lacked prior combat experience, his appointment as Vice-General indicates the court recognized his potential as a strategist and tactician.

Meanwhile, in the Tōhoku region in 792, Emishi leaders from Shiba Village and Isawa Village sent envoys to the Mutsu provincial government, expressing their desire to submit to imperial rule but claiming to be obstructed by Emishi fushu (captives) from Iji Village. Initially, the court was wary of such claims, suspecting deceit. However, by July 792, the imperial court's stance shifted, acknowledging Emishi leaders such as Nisannan Kō Awaso and Ukanmai Kō Inka who sought to submit. They were welcomed to Nagaoka-kyō in November 792, where they received court ranks and gifts, suggesting a new policy of appeasement was being pursued.

In 793, the title of Sei-tō Shi was changed to Sei-i Shi (Expeditionary Force to Subjugate the Barbarians), and on February 21, Tamuramaro made his formal farewell to the Emperor before the campaign. On February 1, 794, Otomaro's expedition departed. The campaign was also reported to Emperor Kōnin's mausoleum and Emperor Tenji's mausoleum, and offerings were made to Ise Grand Shrine to pray for victory.

The specific details of the battle in 794 are largely unknown due to the loss of relevant sections in the Nihon Kōki. The Nihon Kiryaku only briefly notes that "Vice-General Sakanoue no Ōsukune Tamuramaro and others subjugated the Emishi." By late October 794, near the end of the campaign, the imperial army's reported achievements included 457 decapitations, 150 captives, 85 horses captured, and 75 settlements burned. In November 794, the capital was officially named Heian-kyō. On January 29, 795, Otomaro returned to Heian-kyō in triumph. Tamuramaro was promoted to Junior Fourth Rank, Lower Grade, and appointed Mokushō-no-kami (Director of the Bureau of Construction).

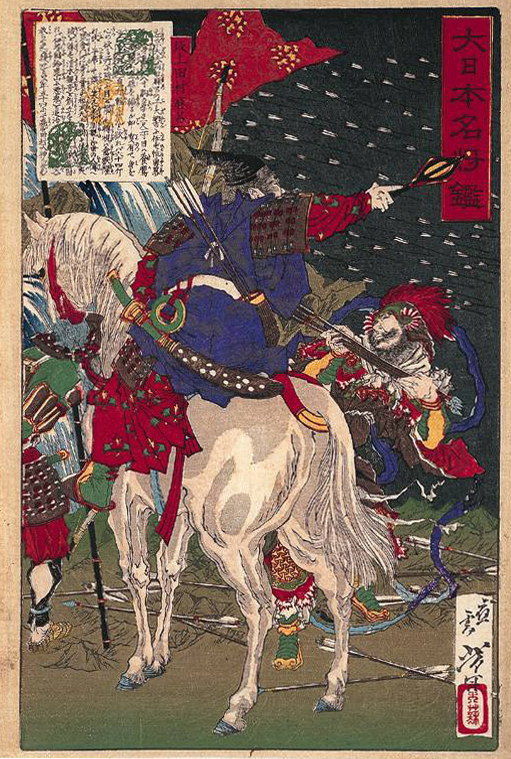

3.1.2. Second Emishi Expedition (Enryaku 20)

In 796, Tamuramaro was appointed Mutsu Dewa Azechi (Inspector-General of Mutsu and Dewa Provinces), Mutsu no Kami (Governor of Mutsu Province), and Chinjufu Shōgun (Commander of the Garrison). These appointments gave him comprehensive administrative and military control over the northern region. On November 5, 797, he was appointed Sei-i Taishōgun by Emperor Kanmu, becoming the second person to hold this title after Ōtomo no Otomaro. Although the third Emishi expedition under Emperor Kanmu was launched three years later in 801, records detailing Tamuramaro's preparations are largely missing. He was promoted to Junior Fourth Rank, Upper Grade, in 798 and Konoe Gon Chūjō (Provisional Middle Captain of the Inner Palace Guards) in 799. By 800, his full title was Sei-i Taishōgun, Konoe Gon Chūjō, Mutsu Dewa Azechi, Junior Fourth Rank Upper Grade, Mutsu no Kami, Chinjufu Shōgun.

On February 14, 801, at the age of 44, Tamuramaro departed from Heian-kyō as Sei-i Taishōgun, having been granted the settō (imperial sword). His army consisted of 40,000 men, with five army supervisors and 32 sergeants. Records for this campaign are sparse, but by September 27, 801, it was reported that "Sei-i Taishōgun Sakanoue no Sukune Tamuramaro and others have subjugated the Emishi," indicating the successful conclusion of the campaign. The term "subjugated" (討伏, tōfuku) emphasized the success of the Emishi conquest. Upon his triumphant return to the capital on October 28, 801, he returned the settō. On November 7, 801, an imperial edict praised his achievements in suppressing the Emishi, who had "repeatedly invaded the borders and killed and plundered the people for generations," and he was promoted to Junior Third Rank. In December, he was appointed Konoe Chūjō (Middle Captain of the Inner Palace Guards).

3.1.3. Construction of Isawa and Shiwa Castles

Following the successful subjugation of the Emishi, Tamuramaro undertook significant construction projects to consolidate imperial control over the newly acquired territories. On January 9, 802, Tamuramaro was dispatched to Mutsu Province as Zō Mutsu-koku Isawa-jō Shi (Supervisor for the Construction of Isawa Castle in Mutsu Province). Two days later, an imperial edict ordered the relocation of 4,000 rōnin (masterless warriors or vagrants) from ten different provinces to the vicinity of Isawa Castle to populate and secure the newly pacified region. Historically, the construction of Isawa Castle was considered a catalyst for the surrender of Emishi leaders like Aterui. However, recent scholarship suggests that the construction only began after peace negotiations led to the formal surrender of Aterui and others, allowing for large-scale construction to commence. On January 20, 802, Tamuramaro was granted one doja (ordained monk), possibly to pray for the souls of those lost in the conflict or for the spiritual enlightenment of the Emishi.

On March 6, 803, Tamuramaro was again dispatched to Mutsu Province as Zō Shiwa-jō Shi (Supervisor for the Construction of Shiwa Castle), receiving a large quantity of silk and cotton for the project. These castles were strategically important for administering and controlling the frontier regions, solidifying Japanese presence in Tohoku.

3.1.4. Surrender and Execution of Aterui and More

On April 15, 802, while Isawa Castle was under construction, the Emishi leaders Ōtomo no Aterui and Iwanogu no More, along with over 500 of their followers, surrendered to Sakanoue no Tamuramaro. Their stronghold had already been conquered, and other Emishi tribal chiefs in the north had already submitted, leaving Aterui and More in a desperate situation. Some scholars suggest that the ancient Chinese ritual of menbaku taimyo (binding hands behind the back and presenting oneself to await judgment) may have occurred during their surrender, though historical records do not explicitly state this. It is more likely that their surrender was the result of extensive peace negotiations, making such a harsh ritual improbable.

On July 10, 802, Tamuramaro accompanied Aterui and More towards Heian-kyō. The Nihon Kiryaku only states that "Tamuramaro came" and does not explicitly say that Aterui and More "entered the capital." The phrase "the two Emishi leaders accompanied" suggests they were not yet treated as prisoners at this point. On July 25, the imperial court celebrated the pacification of the Emishi.

However, on August 13, 802, Aterui and More were executed in Kawachi Province, due to their status as leaders of the "northern barbarians." The Nihon Kiryaku records a debate among the court nobles regarding their fate. Tamuramaro advocated for their return to Isawa, arguing, "This time, we should grant the wishes of Aterui and More and send them back to Isawa, so we can win over and integrate the remaining barbarians." However, the court nobles strongly opposed this, stating, "Their hearts are like wild beasts, and they frequently break their promises. To release such rebel leaders, whom we have finally captured through the awe of the imperial court, back into the remote regions of Mutsu, as Tamuramaro advocates, is like raising a tiger to leave future trouble." The court sided with the nobles, leading to the execution of Aterui and More at a location in Kawachi Province (various theories exist regarding the exact mountain). Although records are scarce, it is widely believed that Emperor Kanmu, prioritizing imperial prestige and the justification of the Emishi campaigns, ultimately decided on their execution, despite Tamuramaro's pleas. Given his presence at the court meeting, Tamuramaro was likely not present at the execution site.

3.1.5. Construction of Shiwa Castle

In 803, Tamuramaro began the construction of Shiwa Castle in Mutsu Province. This strategic fortress was designed to secure the newly expanded territory and further solidify imperial control over the Emishi.

3.2. Political Career and Promotions

Tamuramaro's influence extended beyond military affairs, as he held significant political appointments and rose through the ranks of the imperial court.

3.2.1. The Tokusei Debate

In 804, a fourth Emishi expedition was planned under Emperor Kanmu, with preparations including the transport of large quantities of provisions to Mutsu Province. Tamuramaro was reappointed Sei-i Taishōgun, with three vice-generals, eight supervisors, and 24 sergeants. During this time, Tamuramaro also served as Zō Saiji Chōkan (Supervisor of Construction of the Western Temple) in May 804 and was dispatched to Izumi and Settsu Provinces to select sites for the Emperor's temporary palaces. In October, he accompanied Emperor Kanmu on a hunting trip in Inoino, Izumi Province, where he presented gifts and received 200 kin of cotton. His title at this time was Sei-i Taishōgun, Junior Third Rank, Konoe Chūjō, Zō Saiji Chōkan, Mutsu Dewa Azechi, Mutsu no Kami, Second Class Order of Merit.

On June 23, 805, at the age of 48, Tamuramaro was appointed Sangyō (Councillor), marking the first time a member of the Sakanoue clan had achieved this high political office. On October 19, 805, Kiyomizu-dera was granted an imperial seal, and a decree recognized it as the Sakanoue clan's private temple.

The "Tokusei Debate" (徳政相論), a crucial political discussion, occurred on December 7, 805. During this debate, Fujiwara no Otsugu, a 32-year-old councillor, argued that the primary burdens on the populace were military campaigns and construction projects, proposing that discontinuing these two would bring peace to the people. While the arguments against his proposal are not fully recorded, the 65-year-old councillor Sugano no Mamichi is noted to have "held firmly to his different opinion and refused to listen." Emperor Kanmu, however, accepted Otsugu's advice, leading to the cancellation of the fourth Emishi expedition. Although Tamuramaro was likely present at this debate, he lost the opportunity to lead another major military campaign in Mutsu. Despite this, he retained the title of Sei-i Taishōgun for the remainder of his life, an exception to the temporary nature of the office, indicating it had become a special privilege or honor for him.

3.2.2. Kusuko Incident (Heizei Retired Emperor's Uprising)

On March 17, 806, Emperor Kanmu died, and Crown Prince Ate no Shinno (later Emperor Heizei) ascended the throne. Tamuramaro, along with Fujiwara no Kadonomaro, supported the new emperor during this transition. Heizei's reign focused on reducing government spending and streamlining central agencies.

On April 18, 806, Tamuramaro was appointed Chūnagon (Middle Counselor), and on April 21, he became Chūei Taishō (Commander of the Middle Palace Guards). On May 18, Emperor Heizei's enthronement ceremony was held, and the era name was changed to Daidō. On October 12, 806, Tamuramaro, holding the titles of Chūnagon, Sei-i Taishōgun, Junior Third Rank, Chūei Taishō, Mutsu Dewa Azechi, Mutsu no Kami, Second Class Order of Merit, petitioned for the appointment of additional competent and brave individuals as gunji (district chiefs) and gunki (military commanders) in Mutsu and Dewa Provinces, beyond the regular quota, to strengthen border defenses. This policy, known as ginin gunji/gunki, aimed to satisfy the honor of local elites and stabilize the frontier, marking Tamuramaro's final direct policy concerning the Tohoku region.

In 807, the Chūei-fu was renamed Ukon'e-fu, making Tamuramaro Ukon'e no Taishō (Major Captain of the Right Division of Inner Palace Guards). On August 14, he also became Jijū (Chamberlain), which, given his rank, was a testament to Emperor Heizei's deep trust in him. Shortly after, in October, the Iyo Shinno Incident occurred, leading to the suicide of Prince Iyo and his mother, Fujiwara no Yoshiko, in November. Tamuramaro's specific actions during this event are not recorded. On November 16, he also assumed the post of Hyōbu-kyō (Minister of War). By March 30, 809, he had surpassed his father's rank, reaching Senior Third Rank.

In 809, Emperor Heizei abdicated due to ill health, and Prince Kamino ascended as Emperor Saga. Fujiwara no Kusuko and her brother Fujiwara no Nakanari, who were favored by Heizei, opposed this. After abdicating, Heizei's health recovered, and he ordered the repair of Heijō-kyō in November 809, moving there in December. This created a situation of "two imperial courts." On September 6, 810, Heizei issued an imperial edict to relocate the capital back to Heijō-kyō, triggering the Kusuko Incident. Emperor Saga, initially appearing to comply, appointed Tamuramaro, Fujiwara no Fuyutsugu, and Ki no Tanaue as supervisors for the construction of the Heijō-kyō palace.

However, on September 10, 810, Emperor Saga decisively rejected the capital transfer. He dispatched forces to secure the checkpoints in Ise, Ōmi, and Mino Provinces, arrested Nakanari, and stripped Kusuko of her position. On this day, Tamuramaro was promoted to Dainagon (Major Counselor), and his son, Sakanoue no Hirono, was sent to secure the Ōmi checkpoint. Enraged, Heizei and Kusuko left Heijō-kyō on September 11, intending to raise an army in the eastern provinces. Emperor Saga dispatched Tamuramaro to intercept them. Tamuramaro requested that his former subordinate, Fumiya no Watamaro, who was imprisoned on suspicion of supporting Heizei, be allowed to accompany him. Emperor Saga granted this, promoting Watamaro to Senior Fourth Rank, Upper Grade, and Sangyō. That night, Nakanari was killed. Through Emperor Saga's swift actions, Heizei's advance was halted by Tamuramaro's forces at Uji and Yamazaki on September 12. Realizing he was blocked, Heizei returned to Heijō-kyō, shaved his head, and became a monk, while Kusuko committed suicide by poison, ending the conflict in favor of Emperor Saga. During this incident, Kūkai reportedly prayed for the nation's protection and Tamuramaro's victory.

4. Death and Posthumous Veneration

Sakanoue no Tamuramaro's passing was met with profound grief and marked by extraordinary imperial recognition, leading to his enduring veneration. This section covers his death, burial, and the various tombs and memorials dedicated to him.

4.1. Death and Funeral

On May 23, 811, Sakanoue no Tamuramaro died at the age of 54 in his private residence in Awata, a suburb of Heian-kyō (modern-day Kyoto's Sakyō-ku). Emperor Saga expressed deep sorrow, suspending all political affairs for a day and composing a Chinese poem in praise of Tamuramaro's achievements. On the same day of his death, Emperor Saga ordered an unusually generous distribution of goods to Tamuramaro's family, including 69 rolls of silk, 101 lengths of dyed cloth, 490 lengths of plain cloth, 76 koku of rice, and 200 laborers, which was a significant increase compared to customary grants. This generosity also acknowledged his daughter, Haruko, who was the mother of Prince Kazurai, a son of Emperor Kanmu.

On May 27, 811, Fujiwara no Kazaramaro and Akishino no Masatsugu were sent to Tamuramaro's residence to posthumously confer the rank of Junior Second Rank upon the late Dainagon Tamuramaro. His funeral was held on the same day. He was granted three chō of land in Kurisu Village, Uji District, Yamashiro Province, as a burial site. His body was interred facing east towards the capital, accompanied by his armor, weapons, sword, halberd, bow and arrows, dried provisions, and salt. It was believed that if the nation faced an emergency, his tomb would sound like drums or thunder, warning of danger. Thereafter, generals departing for war would first visit his tomb to make vows and pray for his protection. Currently, the Nishinoyama Kofun in Yamashina Ward, Kyoto, is widely believed to be his burial site.

4.2. Tombs and Memorials

The "Nishinoyama Kofun" in Kyoto's Yamashina Ward was identified as a possible burial site for Sakanoue no Tamuramaro in 1973 by local historian Haruo Torii, based on studies of the Jōri-sei (ancient land division system). In 2007, Shinji Yoshikawa, a professor at Kyoto University, further supported this theory by cross-referencing descriptions in the Kiyomizu-dera Engi (a historical record of Kiyomizu-dera) and an old map of Yamashiro Province (Tokyo University collection) with the location of the Nishinoyama Kofun. Artifacts unearthed from the Yamashina Nishinoyama Kofun, such as decorative leather belt stones, suggest the deceased was a high-ranking noble of Third Rank or higher, or a Fourth Rank councillor, as white jade was used for these ranks. The presence of iron arrowheads signifies the burial of bows and arrows as grave goods. The age of the clay inkstone found at the site dates from the Nagaoka-kyō period to the early Heian period. The location, period, and contents of the tomb align perfectly with those of Sakanoue no Tamuramaro, making it his presumed burial site today.

At Kiyomizu-dera in Higashiyama Ward, Kyoto, near the main hall, is the Kaisandō (Tamura-dō). In this hall, statues of Sakanoue no Tamuramaro and his wife are enshrined in a zushi (Buddhist altar cabinet) on the main altar, honoring them as the principal founders of Kiyomizu-dera.

The "Shōgun-zuka" (General's Mound) in Higashiyama, Kyoto, is a kofun (ancient tumulus) that is part of a cluster of three circular burial mounds. Over time, it became associated with Sakanoue no Tamuramaro and his role as a guardian deity protecting the imperial capital, Heian-kyō. The legend of the Shōgun-zuka rumbling or emitting thunder during national emergencies, as described in the Tamura Maro Denki concerning Tamuramaro's own tomb, became integrated with this mound, even though they were originally distinct. The Heike Monogatari describes Shōgun-zuka as a mound on Mount Kacho in Higashiyama, where an 8-shaku (approximately 7.9 ft (2.4 m)) tall armed clay doll was buried in 794 during the relocation of the capital, with prayers for the eternal protection of the capital.

In Sakanoue no Tamuramaro Park in Yamashina Ward, Kyoto, a monument explicitly named "Tomb of Sakanoue no Tamuramaro" was erected in 1895 during the 1,100th anniversary of the Heian capital relocation. However, this site is now considered part of the Nakatomi archaeological complex, and the tomb is believed to belong to a prominent member of the Nakatomi clan. The monument's gravestone is engraved with the Maru ni Dakimyōga (ginger leaves in a circle) crest.

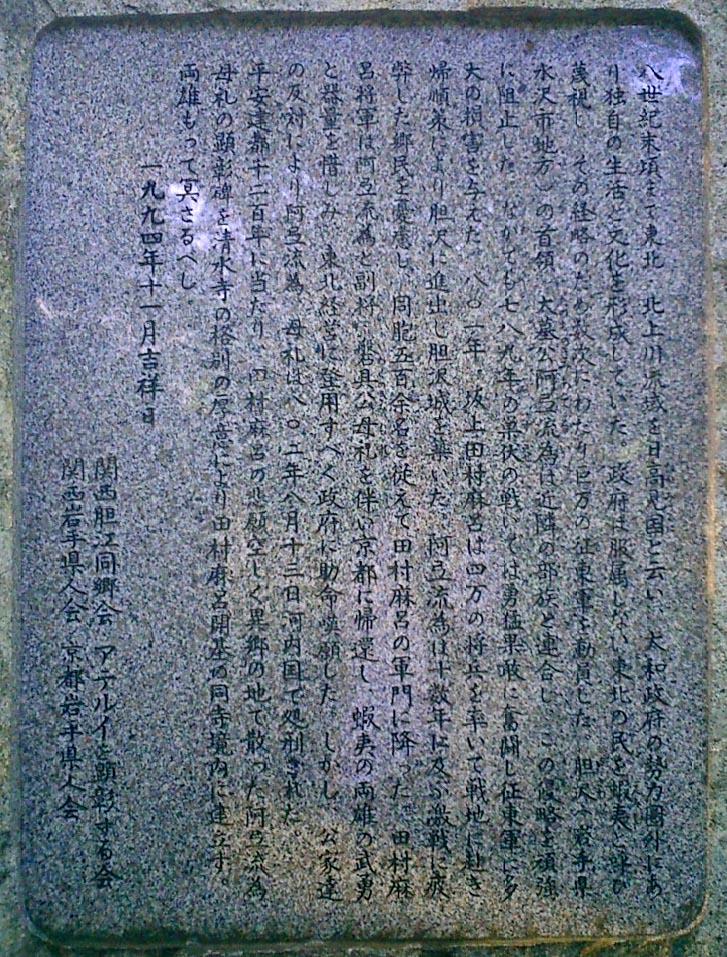

In Wakuya Town, Tōda District, Miyagi Prefecture, and Ishinomaki City, Miyagi Prefecture, memorial towers for Sakanoue no Tamuramaro were erected in 1807 to commemorate the 1000th anniversary of his death.

Several Shinto shrines across Japan are dedicated to Sakanoue no Tamuramaro, including:

- Tamagawa Jinja in Setana Town, Hokkaidō.

- Ichinoseki Hachiman Jinja Aidono Tamura Jinja (former Ichinoseki Castle site) in Ichinoseki City, Iwate Prefecture.

- Tamura Jinja in Takizawa City, Iwate Prefecture.

- Tamura Jinja in Shiroishi City, Miyagi Prefecture.

- Tamura Jinja within the grounds of Koshio Jinja in Akita City, Akita Prefecture.

- Tamura Jinja in Yokote City, Akita Prefecture.

- Tamura Jinja in Tamura Town, Kōriyama City, Fukushima Prefecture.

- Sakanoue no Tamura Myōjin within the grounds of Sumiyoshi Jinja in Azumino City, Nagano Prefecture.

- Tamura Jinja in Hamana Ward, Hamamatsu City, Shizuoka Prefecture.

- Katayama Jinja in Kameyama City, Mie Prefecture.

- Tamura Jinja in Koka City, Shiga Prefecture.

- Tamura-sha within the grounds of Kuwazu Jinja in Hirano Ward, Osaka City, Osaka Prefecture.

- Matsuo Jinja in Takarazuka City, Hyōgo Prefecture.

- Suzuka Jinja in Hashimoto City, Wakayama Prefecture.

- Kōsanpō Kōjinja in Hashimoto City, Wakayama Prefecture.

- Ōma Jinja in Kumano City, Mie Prefecture.

- Tsukushi Jinja in Chikushino City, Fukuoka Prefecture.

5. Beliefs and Legacy

Sakanoue no Tamuramaro's deep personal faith and his symbolic significance as a protector of the realm contributed significantly to his enduring legacy. This section examines his religious activities and temple foundations, followed by his deification and the legends that arose around him.

5.1. Religious Activities and Temple Foundations

Tamuramaro is famously associated with the founding of Kiyomizu-dera in Kyoto, a major Buddhist temple. The exact circumstances of its founding vary across different origin stories, but historical accounts generally place its establishment around 780 or 798. Kiyomizu-dera was initially opened as a sub-temple of Kojima-dera by its second abbot, Enchin, and Tamuramaro.

In 805, Tamuramaro was granted the temple's land by an imperial decree. In 810, Kiyomizu-dera received official recognition through an imperial edict personally written by Emperor Saga, along with an imperial seal, and was given the official name "Hokkan'onji" (North Kannon Temple). In contrast, Kojima-dera was sometimes referred to as "Nankan'onji" (South Kannon Temple). Tamuramaro was a devoted follower of Ekādaśamukha Avalokiteśvara Bodhisattva. It is also said that Emperor Heizei ordered Tamuramaro to build the Fujisan Hongū Sengen Taisha (Mt. Fuji Sengen Shrine) in 806.

5.2. Deification and Legends

From his lifetime, Sakanoue no Tamuramaro was considered an incarnation of Bishamonten (the Buddhist Guardian King of the North), especially noted in the Kugyō Honnin (Official Record of Court Nobles) which states, "Bishamon's incarnation, who came to protect our nation." This belief in him as a divine figure, particularly as a guardian of the north, spread widely.

The Gokuraku-ji (present-day Kunimi-yama Haiji ruins) in Mutsu Province, established as a northern guardian for Isawa Castle, became an officially recognized temple in 857. As Isawa Castle continued to function as a military headquarters until the Later Three Years' War, the belief in Tamuramaro as an incarnation of Bishamonten easily integrated into the region. At the Bishamon-dō of Gokuraku-ji, a legend arose that Sakanoue no Tamuramaro consecrated a statue of Tobatsu Bishamonten, 100 Bishamonten statues, and Shiten'nō statues for the subjugation of foreign enemies.

During the 10th and 11th centuries, when Gokuraku-ji was at its peak, Bishamonten worship linked to Tamuramaro spread throughout the Kitakami River basin, leading to the establishment of numerous Bishamon-dō temples such as Narushima Bishamon-dō, Tachibana Manpuku-ji, and Fujisato Atago Jinja in the Kitakami region. The Tobatsu Bishamonten statue at Narushima Temple is estimated to be from the early 10th century, and the Bishamonten statue at Fujisato Temple from the 11th century, coinciding with the peak of the Abe clan's power in Ōshū Rokugun (Six Districts of Ōshū). An inscription inside the Eleven-faced Kannon statue at Narushima Temple, dated 1098, mentions a descendant of the Sakanoue clan, indicating their continued activity in the Tohoku region even after the Later Three Years' War.

The military tale Mutsu Waki, composed around the late 11th century and set during the Former Nine Years' War in the Six Districts of Ōshū, features the widespread Bishamonten worship associated with Tamuramaro. It concludes by praising Minamoto no Yoriyoshi's achievements by equating them with Tamuramaro's, stating, "Our court, in ancient times, often sent large armies and spent much national resources, but the barbarians were not greatly defeated. Tamuramaro, seeking surrender, subjugated all the barbarians of the six districts and alone established a glorious name for all generations. Truly, he is a manifestation of the Northern Heaven, a rare and distinguished general." This passage highlights the intention to laud Yoriyoshi by placing him on par with Tamuramaro, the "manifestation of the Northern Heaven" (interpreted as an incarnation of Bishamonten, the guardian of the north).

Records from 1126 mention a Sakanoue clan member among the officials of the Ōshū Fujiwara clan's government in Hiraizumi. As Bishamonten worship spread to Hiraizumi, it influenced the legends of Takkokunoi Bishamon-dō (also known as Takkoku Saikō-ji), which claims to be the birthplace of the Tamura faith, where "General Sakanoue no Tamuramaro is a deity, and Bishamon is his original manifestation." During the prosperous period of the Ōshū Fujiwara clan in Hiraizumi, the legend of Akuro-ō became associated with Tamuramaro, as recorded in the Azuma Kagami.

6. Later Assessments and Cultural Impact

Sakanoue no Tamuramaro's influence extended far beyond his lifetime, shaping historical perceptions, inspiring folklore, and continuing to resonate in popular culture. This section examines his historical assessment, the numerous folk legends that emerged, and his portrayal in popular media.

6.1. Historical Assessment

Throughout the Heian period, Tamuramaro was revered as an exceptional warrior. In later eras, he was often cited as a symbol of military prowess, comparable to Sugawara no Michizane, who represented scholarly excellence, making them the dual symbols of civil and military arts. The Ryōunshū collection of Chinese poems includes a lament for Tamuramaro by Ono no Minemori.

In medieval literature, Tamuramaro was counted among the four legendary warriors, alongside Fujiwara no Toshihito, Fujiwara no Yasumasa, and Minamoto no Yorimitsu. Even in the 16th century, Uesugi Kenshin invoked Tamuramaro's name in a prayer for victory at Kosuge-yama.

Before World War II, in the First Higher School (predecessor to the College of Arts and Sciences, University of Tokyo, and the Faculties of Medicine and Pharmaceutical Sciences, Chiba University), portraits of Sugawara no Michizane and Sakanoue no Tamuramaro were displayed in the ethics lecture hall as representatives of civil and military scholars, respectively, for the purpose of student education.

In 1887, Minister of Finance Matsukata Masayoshi proposed to Prime Minister Itō Hirobumi that seven historical figures be depicted on new banknotes: Yamato Takeru, Takenouchi no Sukune, Fujiwara no Kamatari, Prince Shōtoku, Wake no Kiyomaro, Sakanoue no Tamuramaro, and Sugawara no Michizane. Tamuramaro was initially selected for the new 5 yen banknote. However, in 1915, the adoption of Tamuramaro's portrait was suddenly canceled in favor of Takenouchi no Sukune. The exact reason for this change is unknown, but it was widely rumored that it was due to Tamuramaro's presumed immigrant ancestry, despite his significant contributions to the imperial house as a warrior. Consequently, Tamuramaro remained the only one of the seven selected figures from 1887 who never appeared on Japanese banknotes, even after the post-war order by GHQ to remove imperial portraits from currency.

6.2. Folk Legends and Tales

Tamuramaro became a prominent figure in Japanese folklore, often appearing as a heroic exterminator of oni (demons) and bandits. Numerous legends about his demon-slaying exploits are concentrated in the Suzuka Pass area, spanning Mie and Shiga Prefectures. For example, Katayama Jinja in Kameyama City, Mie Prefecture, was depicted in the Edo period travel guide Ise Sangū Meisho Zue as a site dedicated to Tamuramaro, located opposite Suzuka Shrine with the Mirror Rock between them. This suggests an ancient belief in Tamuramaro as a guardian deity, similar to the Shōgun Jizō (General Jizō Bodhisattva) on Mount Atago near Kyoto, and a barrier-god (Sai no Kami) aligned with Suzuka Gongen.

In Koka City, Shiga Prefecture, Tamura Jinja is believed to have been built where Tamuramaro shot an arrow, proclaiming that its merit would protect all people from calamities. Other sites include Kita-muki Iwaya Senju Kannon, where he prayed before defeating demons, Zenshō-ji Temple, said to house the head of the defeated demon Ōtakemaru, and Ichino-o-dera Temple, where he enshrined Bishamonten in gratitude for pacifying mountain bandits. At Banshū Kiyomizu-dera in Kato City, Hyōgo Prefecture, temple tradition states that Tamuramaro donated his treasured sword, Sohayano Tsurugi, and two companion swords after defeating the demons of Suzuka Mountain through the divine power of Kannon Bodhisattva. The swords associated with Tamuramaro also include the Imperial Sword Saka Family Treasure Sword and the Black Lacquer Sword.

Legends about Tamuramaro are also prevalent throughout the Tohoku region, especially in Iwate, Miyagi, and Fukushima Prefectures. These often depict him as a warrior who achieved victory over the Emishi or demons with the aid of specific deities or Buddhas, leading to the founding of temples and shrines. While some tales connect him to areas he likely never reached, such as Aomori Prefecture, most are considered later embellishments, with the exception of Kiyomizu-dera in Kyoto. Other folklore attributes the discovery of hot springs or the resting places of stones to Tamuramaro. Such legends extend across the Kanto, Chubu, Kansai, and Chūgoku regions, with prominent examples including Kashima Shrine in Ibaraki Prefecture, Kohata Jinja in Tochigi Prefecture, Matsuo Jinja in Nagano Prefecture, and Iwamizu-dera in Shizuoka Prefecture.

These pervasive legends fostered various narratives, including the Noh play Tamura (a shura noh or warrior play), which links Tamuramaro to the founding of Kiyomizu-dera and his pacification of demons in Suzuka Province. Medieval tales like Suzuka no Sōshi and Tamura no Sōshi blended Tamuramaro with the legends of Fujiwara no Toshihito and the figure of Suzuka Gozen (also known as Tachi Eboshi), incorporating stories of his defeat of Akuji no Takamaru in Ōmi Province and Ōtakemaru of Suzuka Mountain. These narratives evolved into the Ōjōruri (a form of puppet theater) masterpiece, Tamura Sandaiki, widely performed in the Tohoku region during the Edo period.

6.3. In Popular Culture

Sakanoue no Tamuramaro has been reinterpreted and depicted in various forms of modern popular culture:

- Novels:

- Mutsu Kōchūki (陸奥甲冑記) by Sawada Fujiko (1981), which won the 3rd Eiji Yoshikawa Literary Newcomer Award.

- Kaen (火怨) by Takahashi Katsuhiko (1999), which depicts the conflict between Tamuramaro and Aterui from the perspective of Aterui and the Emishi, winning the 34th Eiji Yoshikawa Literary Award.

- Black to the Future: Sakanoue no Tamuramaro Den (ブラック・トゥ・ザ・フューチャー 坂上田村麻呂伝) by Sataka Rei, illustrated by Yatsumori Kei (2017).

- Television Dramas:

- Kaen: Kita no Eiyū Aterui Den (火怨・北の英雄 アテルイ伝) (2013, NHK BS Historical Drama), where Tamuramaro was portrayed by Takashima Masahiro.

- Manga:

- Tamuramaro-san (たむらまろさん) by Yukimura.

- Noh Plays:

- Tamura (田村), a shura noh play attributed to Zeami Motokiyo.

- Festivals:

- The famous Aomori Nebuta Matsuri (and Neputa Festival in Hirosaki City), which features gigantic illuminated paper floats, was once popularized as a remembrance of Sakanoue no Tamuramaro's campaign to subdue tribal societies in Tohoku. According to legend, Tamuramaro ordered huge illuminated lanterns to be placed on hilltops to attract the curious Emishi, who were then captured. Until the mid-1990s, the prize for the best float was called the Tamuramaro Prize. However, there is no historical record that Tamuramaro traveled farther north than Iwate Prefecture, leading to a reevaluation of the festival's historical ties to him.

- Other:

- Shihō-ryū: An ancient martial arts style that is said to have been revived by Tamuramaro.

- Miharu Goma: Traditional wooden horses from Miharu are believed to have originated from Tamuramaro's campaigns.

- Tsubo no Ishibumi: A legendary stone monument, sometimes associated with Tamuramaro.

- Tamuramaru: The name of the second Seikan Ferry.

7. Family

Sakanoue no Tamuramaro was the son of Sakanoue no Karitamaro, a Junior Third Rank official and Director of the Left Capital Division, who also held the Second Class Order of Merit. His mother's identity is not definitively known. Before Tamuramaro's rise, the Sakanoue clan primarily consisted of local magnates and lower-ranking officials. This section details his immediate family, including his wife, children, and their descendants.

His wife was Miyoshi no Takako, the daughter of Miyoshi no Kiyotsugu. They had several children, including:

- Sons:

- Sakanoue no Ōno: Junior Fifth Rank, Lower Grade, Mutsu Gon no Suke (Provisional Assistant Governor of Mutsu Province). He initially inherited the family headship but died young.

- Sakanoue no Hirono: Junior Fourth Rank, Lower Grade, Uhyōe no Suke (Assistant Director of the Right Division of Palace Guards), Seventh Class Order of Merit. He succeeded Ōno but also died young.

- Sakanoue no Kiyono: Senior Fourth Rank, Lower Grade, Uhyōe no Suke. He succeeded Hirono.

- Sakanoue no Masano: Junior Fourth Rank, Lower Grade, Uhyōe no Suke, Kurodo Jibu no Taifu Tenrakutō (Director of the Bureau of Music) and Kiyomizu-dera Betto (Administrator).

- Sakanoue no Shigeyuki: Adopted the name Adachi Gorō.

- Sakanoue no Tsuguno: Senior Sixth Rank, Upper Grade, Ōtoneri (Grand Palace Attendant).

- Sakanoue no Tsuguo: Adopted the name Musha Nanarō.

- Sakanoue no Hiroo: Junior Fifth Rank, Lower Grade, Ukon Shōgen (Junior Military Official of the Right Division of Palace Guards).

- Sakanoue no Takao: Adopted the name Sōsa Kurō.

- Sakanoue no Takaoka: Adopted the name Nuttari Jirō.

- Sakanoue no Takamichi: Junior Fifth Rank, Upper Grade, Yamato no Suke (Assistant Governor of Yamato Province), Chinjufu Shōgun.

These "Sakanoue main family" lineages (Ōno, Hirono, Kiyono) were considered the principal lines. Some of his sons, such as Shigeyuki, Tsuguo, Takao, and Takaoka, are mentioned only in the Sakanoue-shi Keizu (Sakanoue Clan Genealogy) and are believed to have settled in provincial areas, taking on names similar to later samurai, suggesting they may have been later additions to the genealogy.

- Daughters:

- Sakanoue no Haruko: Became a consort of Emperor Kanmu and bore Prince Kazurai. Her lineage contributed to the Seiwa Genji clan through Prince Kazurai, who later became the ancestor of Minamoto no Tsunemoto.

- Mother of Fujiwara no Arita: Wife of Fujiwara no Mimori.

Other siblings of Tamuramaro mentioned in historical records include Sakanoue no Ishitsumaro, Sakanoue no Hiroto, Sakanoue no Takaaki, Sakanoue no Naozumi, Sakanoue no Takaaki, and Sakanoue no Ooyumi. He also had two sisters: Sakanoue no Mataji, a consort of Emperor Kanmu, and Sakanoue no Tokuko, who married Fujiwara no Uchimaro. Sakanoue no Mii-ko, who received a court rank in 810 along with other consorts of Emperor Saga, is speculated to be another daughter of Tamuramaro, though not explicitly listed in his family tree.

Descendants of Tamuramaro continued the clan's martial tradition, with many serving as high-ranking officials in Mutsu Province, such as Mutsu no Kami (Governor of Mutsu Province), Mutsu no Suke (Assistant Governor of Mutsu Province), Chinjufu Shōgun (Commander of the Garrison), and Chinjufu Fuku Shōgun (Vice Commander of the Garrison). The clan also produced hereditary officials for Kiyomizu-dera as well as positions like Uhyōe no Suke, Yamato no Kami, Myōbō Hakase (expert in legal codes), and Saemon no Taii (Senior Lieutenant of the Left Gate Guards) and Kebishi no Taii (Senior Lieutenant of the Imperial Police).

Sakanoue no Yori-to, a Provisional Junior Secretary of Mutsu, is recorded to have been adopted by Fujiwara no Chise, grandson of Fujiwara no Hidesato. The Tamura District in Mutsu Province is said to have been ruled by the Tamura clan, descended from Tamuramaro. However, the clan was temporarily abolished due to the Utsunomiya Shimotsuke incident. In the Edo period, the clan was revived when Date Munemasa, the third son of Date Tadamune, adopted the name Tamura Munemasa, following the will of his mother, Megohime, daughter of Tamura Kiyoaki and wife of Date Masamune. The Tamura clan ruled the Ichinoseseki Domain until the end of the Edo period and were later granted the title of Viscount under the Peerage Act in the Meiji era.

Beyond military and political roles, the Sakanoue clan also produced notable scholars and legal experts, including Sakanoue no Korenori, one of the Thirty-six Immortals of Poetry, Sakanoue no Mochiki, one of the "Five Pear Court Poets," and Sakanoue no Akira-kane, a principal author of the legal treatise Hossō Shiyōshō. The Yamamoto Sakanoue clan, descended from Sakanoue no Yoritsugu (appointed Settsu no Suke by Minamoto no Mitsunaka), produced samurai like Sakanoue no Yoriyasu and the Yamamoto family (Machiguchi family) of the Imadegawa family. The Ikeda Sakanoue clan, founded by Sakanoue no Masanori (5th-generation descendant of Sakanoue no Masano), moved from Kawachi Province to Toyoshima District in Settsu Province and became local lords. However, during the Nanboku-chō period, they aligned with the Southern Court alongside the Ikuji clan and subsequently declined.

8. Chronology

| Japanese Era | Western Year | Date (Lunar) | Age | Event |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hōki 11 | 780 | 23 | Appointed Konoe Shōgen. | |

| Enryaku 4 | 785 | November 25 | 28 | Promoted from Senior Sixth Rank, Upper Grade, to Junior Fifth Rank, Lower Grade. |

| Enryaku 6 | 787 | March 22 | 30 | Also appointed Takumi no Suke. |

| September 17 | 30 | Appointed Konoe Shōshō. | ||

| Enryaku 7 | 788 | June 26 | 31 | Also appointed Echigo no Suke. |

| Enryaku 9 | 790 | March 10 | 33 | Also appointed Echigo no Kami. |

| Enryaku 10 | 791 | January 18 | 34 | Dispatched to Tōkaidō for inspection of soldiers and weapons. |

| July 13 | 34 | Appointed Sei-tō Fuku-shi. | ||

| Enryaku 11 | 792 | March 14 | 35 | Promoted to Junior Fifth Rank, Upper Grade. |

| Enryaku 12 | 793 | February 17 | 35 | Sei-tō Fuku-shi title changed to Sei-i Fuku-shi. |

| February 21 | 36 | Had an audience with the Emperor before the campaign. | ||

| Enryaku 13 | 794 | June 13 | 37 | Sakanoue no Tamuramaro and others began subjugation of Emishi. |

| October 28 | 37 | Ōtomo no Otomaro reported victory. | ||

| Enryaku 14 | 795 | February 7 | 38 | Promoted to Junior Fourth Rank, Lower Grade. |

| February 19 | 38 | Also appointed Mokushō-no-kami. | ||

| Enryaku 15 | 796 | January 25 | 39 | Also appointed Mutsu Dewa Azechi and Mutsu no Kami. |

| October 27 | 39 | Also appointed Chinjufu Shōgun. | ||

| Enryaku 16 | 797 | November 5 | 40 | Appointed Sei-i Taishōgun. |

| Enryaku 17 | 798 | May 24 (leap month) | 41 | Promoted to Junior Fourth Rank, Upper Grade. |

| July 2 | 41 | Founded Kiyomizu-dera in Kyoto. | ||

| Enryaku 18 | 799 | May | 42 | Appointed Konoe Gon Chūjō. |

| Enryaku 19 | 800 | November 6 | 43 | Inspected Emishi fushu relocated to various provinces. |

| Enryaku 20 | 801 | February 14 | 44 | Received the settō (imperial sword). |

| September 27 | 44 | Reported the subjugation of the Emishi. | ||

| October 28 | 44 | Returned to Kyoto and returned the settō. | ||

| November 7 | 44 | Promoted to Junior Third Rank. | ||

| December | 44 | Appointed Konoe Chūjō. | ||

| Enryaku 21 | 802 | January 9 | 45 | Dispatched to Mutsu to build Isawa Castle. |

| January 20 | 45 | Granted one doja (ordained monk). | ||

| April 15 | 45 | Accepted the surrender of Aterui and More and over 500 others. | ||

| July 10 | 45 | Arrived near Heian-kyō with Aterui and More. | ||

| Enryaku 22 | 803 | March 6 | 46 | Had an audience before dispatch as Zō Shiwa-jō Shi. |

| July 15 | 46 | Appointed Gyōbu-kyō (Minister of Justice). | ||

| Enryaku 23 | 804 | January 28 | 47 | Reappointed Sei-i Taishōgun. |

| May | 47 | Also appointed Zō Saiji Chōkan. | ||

| August 7 | 47 | Dispatched with Mishima no Natsugu to Izumi and Settsu Provinces to determine sites for imperial temporary palaces. | ||

| October 8 | 47 | Attended the hunt at Inoino, presented game, and received 200 kin of cotton. | ||

| Enryaku 24 | 805 | June 23 | 48 | Appointed Sangyō (Councillor). |

| October 19 | 48 | Granted the land for Kiyomizu-dera. | ||

| November 23 | 48 | Attended Prince Sakamoto's genpuku (coming-of-age ceremony) and received clothing. | ||

| Daidō 1 | 806 | March 17 | 49 | Supported Crown Prince (later Emperor Heizei) who was overwhelmed by Emperor Kanmu's death. |

| April 1 | 49 | Offered a eulogy for Emperor Kanmu, accompanying Fujiwara no Otomo. | ||

| April 18 | 49 | Appointed Chūnagon. | ||

| April 21 | 49 | Also appointed Chūei Taishō. | ||

| October 12 | 49 | Requested and was granted permission to appoint provisional gunji and gunki in Mutsu and Dewa. | ||

| Daidō 2 | 807 | April 22 | 50 | Appointed Ukon'e no Taishō. |

| August 14 | 50 | Also appointed Jijū (Chamberlain). | ||

| November 16 | 50 | Also appointed Hyōbu-kyō (Minister of War). | ||

| Daidō 4 | 809 | March 30 | 52 | Promoted to Senior Third Rank. |

| Kōnin 1 | 810 | September 6 | 53 | Appointed Zō Heijō-kyō Shi (Supervisor for Heijō-kyō construction). |

| September 10 | 53 | Appointed Dainagon. | ||

| September 11 | 53 | Dispatched to suppress the Kusuko Incident. The following day, the retired Emperor's eastward journey was blocked, and the rebellion ended. | ||

| October 5 | 53 | Granted an imperial seal for Kiyomizu-dera. | ||

| Kōnin 2 | 811 | January 17 | 54 | Expressed joy at his grandson Prince Kazurai's archery skills. |

| January 20 | 54 | Hosted a banquet for Bohai envoys at Chōshūin. | ||

| May 23 | 54 | Died at his private residence in Awata, Yamashiro Province. | ||

| May 27 | Buried in Kurisu Village, Shichijō Kujō Nishizato, Uji District, Yamashiro Province. Posthumously promoted to Junior Second Rank. | |||

| October 17 | Granted three chō of land for his grave. |