1. Early Life and Background

Saichō's early life was marked by a period of significant religious and political transition in Japan, which influenced his spiritual inclinations and path towards establishing a distinct Buddhist tradition.

1.1. Birth and Ancestry

Saichō was born with the given name Hirono (広野HironoJapanese) in Ōmi Province, in what is now Shiga Prefecture, specifically in Furuichi-go of Shiga District (modern Ōtsu City). There is a debate surrounding his exact birth year, with some records, including official documents from his time, indicating 766, while others, such as his posthumous biographies, suggest 767. Some scholars propose that while his official registration might have been 766, Saichō himself believed his birth year to be 767.

According to family tradition, Saichō's ancestors were descendants of emperors of Eastern Han China, specifically an individual named Tōmanki-ō (登萬貴王Tōmanki-ōJapanese) who is said to have arrived in Japan during the reign of Emperor Ōjin. While there is no definitive historical evidence to fully substantiate this claim, the region of Ōmi did have a substantial population of Chinese immigrants, making it plausible that Saichō had Chinese ancestry. His father is recorded as Mitsu-no-obito Momoe (三津首百枝Mitsu-no-obito MomoeJapanese) in some accounts, or Mitsu-no-obito Kiyotari (三津首浄足Mitsu-no-obito KiyotariJapanese), who held a lower eighth rank and served in a vice-governor position. His mother is variously identified as a daughter of Fujiwara Takatori or a ninth-generation descendant of Emperor Ōjin, though these claims are also from later traditions and lack historical certainty.

1.2. Childhood and Early Education

From a young age, Saichō displayed exceptional talent. According to his biographies, he showed non-ordinary abilities in subjects such as Onmyōdō, medicine, and crafts during his elementary education (小学shōgakuJapanese). At the age of seven, he began to aspire to the Buddhist path.

He received his initial exposure to Buddhist teachings at the Ōmi Kokubun-ji temple, where he served as an `優婆塞UpasakaJapanese` (lay devotee) for about three years. During this period, he dedicated himself to studying various Buddhist scriptures, including the Lotus Sutra, Golden Light Sutra, Medicine Buddha Sutra, and Diamond Sutra. This early immersion in the Buddhist canon laid the groundwork for his profound understanding and later doctrinal contributions.

2. Monastic Training and Early Activities

Saichō's journey into monastic life was characterized by a deep commitment to ascetic practice and a growing desire to establish a distinct Buddhist tradition in Japan, setting him apart from the established Nara schools.

2.1. Tonsure and Ordination

At the age of 12, in 778, Saichō entered the Ōmi Kokubun-ji temple and became a disciple of Gyōhyō (行表GyōhyōJapanese). Two years later, in 780, at the age of 14, he underwent tonsure as a novice monk and was given the ordination name "Saichō." Gyōhyō was a significant figure, himself a disciple of Dao-xuan (道璿DàosuìChinese), (道璿DōsenJapanese), a prominent Chinese monk of the Tiantai school who had brought various teachings to Japan, including the East Mountain Teaching of Chan Buddhism, Huayan teachings, and the Bodhisattva Precepts of the Brahmajala Sutra in 736. Gyōhyō's teachings, particularly his emphasis on the "return of the mind to the One Vehicle," profoundly influenced Saichō's later pursuit of a unified Buddhist path.

In 785, at the age of 19, Saichō undertook the full monastic precepts at the Tōdai-ji temple's ordination platform, thereby becoming a fully ordained monk within the official temple system. This formal ordination marked his entry into the mainstream Buddhist establishment of the time.

2.2. Retreat to Mount Hiei

Just a few months after his full ordination in July 785, Saichō abruptly retreated to Mount Hiei for intensive study and practice of Buddhism. While the exact reasons for his departure from the official system remain unclear, it is understood that he sought a deeper, more personal engagement with the Dharma, rather than a rejection of existing Buddhism. He likely followed official procedures for mountain retreat, which allowed monks to pursue quiet practice away from secular affairs.

Upon his retreat, Saichō composed his Ganmon (願文GanmonJapanese), also known as "Saichō's Prayer", which outlined his profound personal vows:

- "So long as I have not attained the stage where my six faculties are pure, I will not venture out into the world."

- "So long as I have not realized the absolute, I will not acquire any special skills or arts [e.g., medicine, divination, calligraphy, etc.]."

- "So long as I have not kept all the precepts purely, I will not participate in any lay donor's Buddhist meetings."

- "So long as I have not attained wisdom (lit. hannya 般若), I will not participate in worldly affairs unless it be to benefit others."

- "May any merit from my practice in the past, present and future be given not to me, but to all sentient beings so that they may attain supreme enlightenment."

In 788, Saichō constructed a small hermitage (草庵sōanJapanese) on Mount Hiei, where he enshrined a self-carved image of the Bhaiṣajyaguru (Yakushi Nyorai). This hermitage later became known as the Ichijō Shikangaku-in (一乗止観院Ichijō Shikangaku-inJapanese), or "One Vehicle Cessation and Contemplation Institute", which would eventually grow into Enryaku-ji. He also lit a lamp of oil before the Buddha, praying that it would never be extinguished; this lamp, known as the Fumetsu no Hōtō (不滅の法灯Fumetsu no HōtōJapanese), or "Inextinguishable Dharma Lamp", has remained lit for over 1200 years. During this period, Saichō meticulously studied the Lotus Sutra and delved into the teachings of Zhiyi, the patriarch of the Chinese Tiantai school, copying texts that had been brought to Japan by Jianzhen.

2.3. Early Court Relations

Saichō's presence on Mount Hiei gained the attention of the imperial court due to its strategic location. The capital of Japan had recently been moved from Nara to Nagaoka-kyō in 784, and then to Kyoto in 795. Mount Hiei's position to the northeast of Kyoto was considered geomantically important, a direction often associated with danger according to Chinese geomancy. Saichō's spiritual activities on the mountain were thus perceived as providing protection for the new capital, elevating his status.

His growing prestige was further enhanced by his correspondence and ceremonial exchanges with the established Buddhist communities in Nara and with monks at the imperial court. One of his earliest and most significant supporters in the court was Wake no Hiroyo (和気弘世Wake no HiroyoJapanese), who invited Saichō to deliver lectures on Tiantai doctrine at Takaosan-ji (高雄山寺Takaosan-jiJapanese), now Jingo-ji, in 802. This invitation, alongside fourteen other eminent monks, signaled Saichō's rising prominence, although he was not the first choice, indicating he was still gaining recognition.

In 791, Saichō was awarded the `修行入位shugyō-nyūiJapanese` (training rank) and in 797, he was appointed as one of the ten `内供奉naigubuJapanese` (court monks), who performed readings and rituals within the imperial palace. Recognizing the need for a comprehensive collection of scriptures, Saichō initiated a large-scale sutra copying project on Mount Hiei in 797. He sent appeals to the Nara temples for assistance, receiving support from monks like Wenjaku (聞寂WenjakuJapanese) of Daian-ji and Dōchū (道忠DōchūJapanese) from Eastern Japan, whose disciples included later prominent figures like Ennin and Enchō. From 798, Saichō began holding annual `法華十講Hokke JikkōJapanese` (Lotus Sutra lectures), inviting high-ranking monks from Nara in 801, further solidifying his connections within the Buddhist community.

3. Journey to Tang China

Saichō's journey to Tang China was a transformative experience that profoundly influenced the development of Japanese Buddhism, enabling him to bring back a wealth of knowledge and texts that would form the basis of the Japanese Tendai school.

3.1. Purpose and Itinerary

Saichō's mission to China was initiated by Emperor Kanmu, who sought to further propagate Buddhist teachings and resolve the traditional rivalry between the East Asian Yogācāra and East Asian Mādhyamaka schools in Japan. The emperor granted Saichō's petition to travel to China to deepen his study of Tiantai doctrine and acquire more texts, with the expectation that he would return relatively quickly.

Saichō, who could read Chinese but not speak it, was permitted to bring a trusted disciple, Gishin (義眞GishinJapanese), who was fluent in Chinese. Gishin would later become a significant figure in the Tendai order. Saichō was part of a four-ship diplomatic mission to Tang China that set sail in 803. After an initial attempt was thwarted by heavy winds, forcing the ships to turn back to Dazaifu, Fukuoka, Saichō likely met Kūkai, another Buddhist monk on a similar mission, though Kūkai was expected to stay in China for a longer period.

When the mission resumed, two ships sank in a severe storm, but Saichō's ship successfully reached the port of Ningbo, then known as Mingzhou (明州MíngzhōuChinese), in northern Zhejiang in 804. After a brief rest due to illness, Saichō and his party departed for Tiantai Mountain on September 15.

3.2. Study of Tiantai and Esoteric Buddhism

Upon arriving in Taizhou (台州TáizhōuChinese) on September 26, Saichō met Daosui (道邃DàosuìChinese), the seventh Patriarch of the Tiantai school, who became his primary teacher. Daosui provided crucial instruction on Tiantai meditation methods, monastic discipline, and orthodox teachings. Saichō remained under Daosui's tutelage for approximately 135 days. During this time, he diligently copied numerous Buddhist works, aiming to bring back fresh, accurate copies to Japan, as he felt existing texts in Japan suffered from copyist errors.

While in Mingzhou, Saichō also studied Chan (specifically 牛頭宗Niútóu ZōngChinese or Ox-head Zen) at Zenrin-ji and Esoteric Buddhism (Mikkyō) at Guoqing-ji. He even oversaw the construction of a hall at Guoqing-ji. In March 805, Saichō and Gishin received the Mahayana Bodhisattva Precepts from Daosui, a pivotal encounter that shaped Saichō's understanding of the Mahayana precepts. His studies on Tiantai Mountain resulted in the acquisition of 120 works in 345 volumes.

As the diplomatic mission prepared for its return, Saichō traveled to Yuezhou (越州YuèzhōuChinese), modern-day Shaoxing, to seek texts and information on Vajrayana (Esoteric) Buddhism. Although the Tiantai school traditionally used "mixed" (`雑密zōmitsuJapanese`) ceremonial practices, Esoteric Buddhism had gained prominence. Saichō received `灌頂kanjōJapanese` (initiation) from Shun-hsiao (順曉ShùnxiǎoChinese) at Longxing-si. While some English sources suggest uncertainty about whether he received both the Diamond Realm and Womb Realm transmissions, Japanese accounts state that Saichō received both. This indicates that Saichō's understanding of Esoteric Buddhism, though perhaps different from Kūkai's later comprehensive transmission, was rooted in a foundational understanding of both aspects. Through this, he acquired 102 works in 115 volumes on Esoteric Buddhism, along with five ritual implements.

3.3. Return to Japan

On May 18, 805, Saichō and his party departed Mingzhou and arrived in Tsushima on June 5. Despite having spent only eight months in China, his return was highly anticipated by the court in Kyoto. He brought back a vast collection of texts and teachings, totaling 230 works in 460 volumes, which he had meticulously copied and acquired. Upon his arrival, Emperor Kanmu, who was ill, requested Saichō to perform prayers for his recovery, highlighting the immediate importance placed on the new teachings he had brought. In September 805, at the request of Emperor Kanmu, Saichō performed the first official `灌頂kanjōJapanese` (abhisheka) ritual in Japan at Takaosan-ji.

4. Founding of the Japanese Tendai School

Saichō's return from China marked the beginning of a new era for Japanese Buddhism, as he established the Tendai school, synthesizing various Buddhist traditions and laying the groundwork for its unique institutional and doctrinal framework.

4.1. Establishment of Enryaku-ji and the School

Upon his return, Saichō diligently sought official recognition for his new school. In January 806, his Tendai Lotus school (天台法華宗Tendai-hokke-shūJapanese) received official imperial recognition through an edict issued by the ailing Emperor Kanmu. This decree permitted two annual ordinands (年分度者nenbundoshaJapanese) for Saichō's new school on Mount Hiei. The ordinands were to be divided between two curricula: the `遮那業shanagōJapanese` course, focused on the study of the Mahavairocana Sūtra (Mikkyō curriculum), and the `止観業shikangōJapanese` course, based on the study of the Mohe Zhiguan, the seminal work of the Tiantai patriarch Zhiyi (Tendai curriculum). This marked the official acknowledgment of Mikkyō as a proper subject of study within Japanese Buddhism from its very inception, making the Tendai Lotus school equally based on both Mikkyō and Tiantai.

Saichō's vision extended beyond simply introducing new teachings; he aimed to establish a new order within the Japanese Buddhist world. In his petition to the court, he argued that the existing system, which recognized only the Sanron and Hosso schools for annual ordinands, was insufficient. He proposed including his Tendai Lotus school along with Huayan and Ritsu schools, aiming to create a more comprehensive and balanced Buddhist landscape. This proposal, which included specific regulations for academic study and appointment, was swiftly approved by the `僧綱sōgōJapanese` (Office of Monastic Affairs) and enacted by a `太政官符DaijōkanpuJapanese` (Grand Council of State decree) on January 26, 806. This date is considered by the Tendai school as its founding day.

Initially, the Tendai school remained under the authority of the Nara Buddhist monastic system. However, Saichō soon realized the challenges of this arrangement. By 818, out of 24 monks ordained under the Tendai system, 14 had left Mount Hiei, with 6 defecting to the Hosso school. This prompted Saichō to express his concern in the Kenkairon, noting that Tendai students were being swayed by minor teachings and abandoning the "perfect path." This situation fueled his later efforts to establish an independent ordination platform on Mount Hiei.

In 813, Saichō composed the Ehyō tendaishū (依憑天台義集Ehyō tendaishūJapanese), in which he argued that the principal Buddhist masters of China and Korea, including those from the Sanlun, Faxiang (Hosso), Huayan, and Mikkyō schools, had all relied on Tiantai doctrine. By identifying numerous references and quotes from Tiantai treatises in their works, Saichō asserted that Tiantai formed the fundamental basis for all major Buddhist schools in East Asia, thereby establishing the intellectual legitimacy and superiority of his newly founded school.

4.2. Core Doctrines and Practices

The foundational teachings of Japanese Tendai, as established by Saichō, represent a synthesis of various Buddhist traditions, centered on the Lotus Sutra and the concept of universal Buddha-nature.

A cornerstone of Saichō's Tendai was the concept of `円密一致enmitsu itchiJapanese` ("identity of the purport of Perfect and Esoteric teachings"). This doctrine asserted a unity and agreement between the teachings of the Lotus Sutra (the "perfect" or exoteric teaching) and Esoteric Buddhism (Mikkyō). Unlike the Shingon school, which viewed esoteric practice as superior, Saichō believed that both provided a direct path (`直道jikidōJapanese`) to enlightenment, in contrast to the longer, more gradual paths offered by the Nara schools. He also emphasized `即身成仏sokushin-jōbutsuJapanese` (attaining Buddhahood in this very body). While Saichō's initial understanding of Mikkyō was somewhat incomplete compared to Kūkai's, he awarded Esoteric Buddhism a more central place in the Tendai tradition than it had been given by most Chinese monks.

Another crucial doctrine championed by Saichō was `一切衆生悉有仏性issai shujō shitsu u busshōJapanese` (all sentient beings possess Buddha-nature). This concept, rooted in the Mahaparinirvana Sutra, asserts that all beings inherently possess the potential to become a Buddha. This directly challenged the `五性各別説goshō kakubetsu-setsuJapanese` (five distinct natures doctrine) of the Hosso school, which held that some beings (`無性有情musei ujōJapanese`) lacked the capacity for Buddhahood. Saichō argued that denying universal Buddha-nature was a "Hinayana" (inferior vehicle) teaching, while his view represented the true "Mahayana" (great vehicle) path. He asserted that those who believe in universal Buddha-nature and engage in altruistic practice are true Bodhisattvas.

The importance of meditation, particularly `止観ShikanJapanese` (cessation and contemplation), was central to Tendai practice. Saichō emphasized the practice of `四種三昧shishu zammaiJapanese` (four types of samadhi): Constant Sitting Samadhi, Constant Walking Samadhi, Half-Walking Half-Sitting Samadhi, and Neither Walking Nor Sitting Samadhi. He planned the construction of dedicated halls for these practices on Mount Hiei, which, though some were completed posthumously, underscored their significance in his vision for monastic training. The `法華堂Hokke-dōJapanese` (Lotus Hall) became a key Zen meditation hall, and the `常行堂Jōgyō-dōJapanese` (Constant Walking Hall) laid the groundwork for later Pure Land practices.

5. Relationship with Kūkai

The relationship between Saichō and Kūkai, two of the most influential figures in early Heian Buddhism, was complex, evolving from initial cooperation and mutual respect to eventual doctrinal and institutional divergence.

5.1. Initial Encounters and Cooperation

Saichō and Kūkai first met in Japan, likely in Dazaifu, Fukuoka Prefecture, in 803, while awaiting their ships for the diplomatic mission to Tang China. Despite their different primary missions-Saichō to study Tiantai and Kūkai to study Esoteric Buddhism-they developed a friendship. Saichō was particularly captivated by the Esoteric (Vajrayana) Buddhist texts Kūkai possessed, recognizing their profound significance.

Upon their return to Japan, Saichō played a crucial role in Kūkai's early recognition. He facilitated Kūkai's performance of the `灌頂kanjōJapanese` (abhisheka) initiation ritual for high priests of the Nara Buddhist establishment and dignitaries of the imperial Heian court. Saichō also endorsed the court's bequest of the mountain temple of Takaosan-ji (Jingo-ji) to Kūkai as the first center for his Shingon Buddhism. In return, Kūkai trained Saichō and his disciples in esoteric Buddhist rituals and lent Saichō various Mikkyō texts he had brought from China, demonstrating an initial period of mutual support and intellectual exchange. Saichō himself received the `金剛界灌頂Kongōkai kanjōJapanese` (Diamond Realm initiation) and `胎蔵界灌頂Taizōkai kanjōJapanese` (Womb Realm initiation) from Kūkai at Otoko-dera (乙訓寺) in 812, along with his disciples Taihan, Enchō, and Kōjō.

5.2. Divergence and Doctrinal Disputes

Despite their initial collaboration, the relationship between Saichō and Kūkai began to deteriorate due to differing interpretations of Esoteric Buddhism, issues regarding monastic precepts, and intellectual rivalry.

One major point of contention was the differing understanding of Mikkyō. Saichō adhered to the concept of `円密一致enmitsu itchiJapanese` (the unity of perfect and esoteric teachings), believing that the teachings of the Lotus Sutra and Esoteric Buddhism were fundamentally the same. In contrast, Kūkai viewed Esoteric Buddhism as superior to exoteric teachings like Tendai. This doctrinal difference became evident when Saichō requested to borrow Kūkai's Rishukyō (理趣経RishukyōJapanese) text. Kūkai refused, stating that esoteric teachings were transmitted orally and from mind to mind, not through written texts to those not fully initiated. This refusal, regardless of whether the specific letter was addressed to Saichō or his disciple Enchō, marked a significant turning point in their relationship.

The issue of monastic precepts further exacerbated their rift. Saichō's top disciple, Taihan (泰範TaihanJapanese), who had been designated as the general administrator of Mount Hiei in Saichō's will, left Mount Hiei in 812 to study exclusively with Kūkai. Despite Saichō's repeated pleas for Taihan to return, Taihan chose to remain with Kūkai, eventually becoming one of Kūkai's ten principal disciples. Kūkai's response to Saichō's entreaties, conveyed through Taihan, explicitly stated the superiority of Shingon's teachings over Tendai.

Saichō's later writings reflected his growing criticism of Shingon. In an introduction added to his Ehyō tendaishū in 816, he denounced Kūkai and Shingon for denying the validity of transmission through writing. This public condemnation highlighted the fundamental differences in their approaches to Buddhist study and transmission. The break between Saichō and Kūkai left a lasting legacy, shaping the complex relationship between the Tendai and Shingon schools throughout the Heian period, characterized by both affiliation and rivalry. Saichō's criticisms of Kūkai would later be cited by Nichiren, the founder of Nichiren Buddhism, in his own debates during the Kamakura period.

6. Efforts to Establish the Mahayana Ordination Altar

Saichō's most significant reformist effort was his tireless campaign to establish an independent Mahayana ordination altar on Mount Hiei, a move that aimed to assert a distinct Japanese Buddhist identity and fundamentally alter the monastic system.

6.1. Monastic Precept Reforms

Saichō critically viewed the existing Vinaya system in Japan, which mandated that all monastic ordinations take place at Tōdai-ji temple under the ancient Prātimokṣa code. He argued that this system, based on Hinayana (lesser vehicle) precepts, was inadequate for the needs of a purely Mahayana institution. His vision was to ordain monks solely using the Mahayana Bodhisattva Precepts, particularly those outlined in the Brahmajala Sutra, which Tendai referred to as `円頓戒endonkaiJapanese` (perfect and sudden precepts).

In 818, Saichō declared his intention to abandon the Hinayana precepts, stating that his community would no longer adhere to the "minor observances" and would instead focus on the Mahayana path. While this act was a symbolic break from the traditional system, neither the imperial court nor the Nara monastic establishment treated it as a formal renunciation of his monastic status. To clarify his position and advocate for his reforms, Saichō composed the Kenkairon (顕戒論KenkaironJapanese, "A Clarification of the Precepts") in 820, emphasizing the profound significance of the Bodhisattva Precepts.

Saichō's proposed ordination method was revolutionary. Unlike the traditional system that required a `三師七証sanshi shichishōJapanese` (three masters and seven witnesses) and adherence to 250 precepts for monks (348 for nuns), Saichō asserted that monks could be ordained solely through the Bodhisattva Precepts. He also proposed a simplified ordination ceremony where Shakyamuni Buddha, Manjushri, and Maitreya would serve as the "three masters," with all Buddhas as witnesses, and only one preceptor was needed. He even suggested that self-ordination (`自誓受戒jisei jukaiJapanese`) would be permissible if no preceptor was available. Furthermore, he argued that the distinction between lay and ordained individuals could be maintained through external appearance (shaved head and robes).

6.2. Assertion of Japanese Buddhist Identity

Saichō's efforts to reform monastic precepts were deeply intertwined with his broader vision for an independent Japanese Buddhist tradition, one that was distinct from direct adherence to Chinese models and capable of fostering a unique national identity.

He formalized this vision in his proposals for a new monastic training system, notably the `山家学生式Sange Gakushō ShikiJapanese` (Regulations for Mountain School Students), submitted to the court between 818 and 819. This document outlined an innovative system of `十二年籠山行jūni-nen rōzan-gyōJapanese` (12-year mountain training) on Mount Hiei, where monks would dedicate themselves to intensive study and practice within the Tendai framework, culminating in ordination on the mountain itself. This was a direct response to the outflow of Tendai monks to Nara temples and aimed to cultivate a dedicated corps of Tendai practitioners.

Within the Sange Gakushō Shiki, Saichō articulated his famous concept of `国宝kokuhōJapanese` (national treasure): "What is a national treasure? A person with a mind seeking enlightenment is called a national treasure. Therefore, ancient philosophers said, 'Ten pearls of one inch in diameter are not national treasures. A person who illuminates a corner of the world is a national treasure.'" This statement emphasized the value of spiritual cultivation and altruistic service to the nation.

Saichō also sought institutional independence for the Tendai school. He proposed that Tendai monks, after receiving Mahayana precepts, should not be registered under the Ministry of Civil Administration (治部省Jibu-shōJapanese), which oversaw the traditional monastic system, but rather remain under the Ministry of Popular Affairs (民部省Minbu-shōJapanese), effectively placing them under direct imperial authority rather than the Nara monastic hierarchy. He also requested that their ordination certificates (`度縁doenJapanese`) bear the official imperial seal, similar to those issued for traditional ordinations. These proposals aimed to establish a self-governing Tendai order with its own unique disciplinary and administrative structure.

Despite intense opposition from the established Nara Buddhist schools, particularly the Hosso school and its prominent monk Tokuitsu, Saichō continued to advocate for his reforms. The Nara monks, led by figures like Gomyō (護命GomyōJapanese), argued against Saichō's proposals, asserting that they lacked doctrinal basis. However, Saichō's persistent efforts bore fruit posthumously. Seven days after his death in 822, Emperor Saga granted imperial approval for the establishment of the Mahayana ordination altar on Mount Hiei, a momentous decision that fundamentally transformed the landscape of Japanese Buddhism and paved the way for the emergence of new, distinct Japanese Buddhist schools.

7. Major Writings and Doctrinal Contributions

Saichō was a prolific writer whose treatises played a crucial role in articulating Tendai doctrine, defending his reforms, and engaging in significant intellectual debates that shaped the philosophical landscape of early Heian Buddhism.

7.1. Key Treatises

Saichō's most important literary works include:

- Shōgon Jikkyō (照権実鏡Shōgon JikkyōJapanese, 817): This work, whose title means "Illuminating the Provisional and the Real," served as Saichō's direct rebuttal to the arguments of Tokuitsu of the Hosso school, particularly concerning the nature of Buddha-nature and the distinction between provisional and true teachings.

- Sange Gakushō Shiki (山家学生式Sange Gakushō ShikiJapanese, 818-819): Titled "Regulations for Mountain School Students," this treatise outlined Saichō's comprehensive plan for the training and ordination of Tendai monks on Mount Hiei, emphasizing the 12-year mountain retreat and the exclusive use of Mahayana Bodhisattva Precepts. It also contains his famous "national treasure" statement.

- Shugo Kokkai Shō (守護国界章Shugo Kokkai ShōJapanese, 818): Meaning "Treatise on Protecting the Nation," this work articulated Saichō's vision of Tendai Buddhism as a protector of the state, arguing that the cultivation of pure Mahayana monks would ensure national well-being and prosperity.

- Kenkairon (顕戒論KenkaironJapanese, 820): "A Clarification of the Precepts," this treatise is a powerful defense of Saichō's proposed Mahayana Bodhisattva Precepts as the sole basis for monastic ordination, directly challenging the traditional Vinaya system and asserting the distinct identity of Japanese Tendai.

- Ehyō tendaishū (依憑天台義集Ehyō tendaishūJapanese, 813): This work, "Collection of Meanings Based on Tiantai," argued for the foundational role of Tiantai doctrine in all major East Asian Buddhist schools, asserting its intellectual primacy.

7.2. Doctrinal Debates

Saichō was a central figure in several significant doctrinal debates of his era, most notably with Tokuitsu (徳一TokuitsuJapanese), a prominent monk of the Hosso school. Their protracted intellectual exchange, known as the `三一権実諍論San-ichi Kenjitsu SōronJapanese` (Three Vehicles vs. One Vehicle, Provisional vs. Real Teachings Debate), spanned from 817 until Saichō's death in 822, with most of Saichō's major writings related to this controversy.

The debate revolved around two main themes. The first concerned the fundamental differences between Tendai and Hosso teachings, particularly regarding spiritual practice. Saichō uniquely criticized Tokuitsu's proposed practices as being suitable only for the "Age of True Dharma" (the period immediately following the Buddha's death) and thus impractical for the approaching "Age of Degenerate Dharma" (`末法mappōJapanese`), emphasizing the need for a "direct path" to enlightenment in later ages.

The second, and perhaps most central, theme was the `三一権実諍論San-ichi Kenjitsu SōronJapanese` itself, which questioned whether the "One Vehicle" (一乗ichijōJapanese) of Tendai or the "Three Vehicles" (三乗sanjōJapanese) of Hosso represented the provisional (権gonJapanese) or real (実jitsuJapanese) teachings. This debate also encompassed the `仏性論busshōronJapanese` (Buddha-nature theory). Tokuitsu supported the `五性各別説goshō kakubetsu-setsuJapanese` (five distinct natures doctrine), which posited that some sentient beings lacked the inherent capacity for Buddhahood. Saichō vehemently countered this, asserting the doctrine of `一切衆生悉有仏性issai shujō shitsu u busshōJapanese` (all sentient beings possess Buddha-nature) and `一切皆成issai kaishōJapanese` (all can attain Buddhahood), arguing that the Hosso position was a "Hinayana" (inferior vehicle) interpretation, while his own represented the true Mahayana path. These debates were crucial in defining the distinct doctrinal identity of the Japanese Tendai school.

8. Later Life and Passing

Saichō's final years were dedicated to solidifying the foundations of the Tendai school and its unique monastic system, culminating in posthumous recognition that cemented his enduring legacy.

8.1. Final Activities and Death

In his later years, Saichō continued to work tirelessly for the establishment of the Mahayana ordination platform. In 822, he was awarded the `伝燈大法師位Dentō Daihōshi-iJapanese` (Great Dharma Master of Lamp Transmission), a high honor. However, his health was declining. On March 17, 822, his disciple Kōjō (光定KōjōJapanese), who served as a liaison with the court, urgently petitioned the emperor, stating that Saichō was gravely ill and that the late Emperor Kanmu's wish for the establishment of the ordination platform would not be fulfilled if permission was not granted soon.

Saichō passed away on June 26, 822, at the Chūdō-in (中道院Chūdō-inJapanese) on Mount Hiei, at the age of 56 (54 by Western reckoning). His burial site is at Jōdo-in (浄土院Jōdo-inJapanese) on Mount Hiei. In his last will, Saichō urged his disciples to continuously lecture on the great sutras, diligently practice for the benefit of the nation and all sentient beings, and perform `護摩gomaJapanese` (fire rituals) annually to express gratitude for imperial favor.

8.2. Posthumous Title and Recognition

A pivotal moment occurred just seven days after Saichō's death. Through the efforts of his disciple Kōjō and influential court officials like Fujiwara Fuyutsugu (藤原冬嗣Fujiwara FuyutsuguJapanese) and Yoshimine no Yasuyo (良岑安世Yoshimine no YasuyoJapanese), Emperor Saga granted imperial approval for the establishment of the Mahayana ordination altar and the Tendai monastic training system on Mount Hiei. This posthumous decree was a testament to Saichō's unwavering dedication and a monumental victory for his reformist vision.

In 823, the Ichijō Shikangaku-in was officially renamed Enryaku-ji by imperial decree. The first ordination under the new Mahayana system took place on March 17, 823, followed by Kōjō and others receiving precepts on April 14. In October of the same year, Emperor Saga composed a poem titled "Lamenting Saichō" (哭澄上人詩Koku Chō Shōnin ShiJapanese), further acknowledging his profound impact.

Saichō received the posthumous title `伝教大師Dengyō DaishiJapanese` (Great Master of Transmitted Teaching) by imperial edict from Emperor Seiwa on July 12, 866. This was the first time a `大師DaishiJapanese` (Great Master) title was bestowed in Japanese history, solidifying his foundational role in Japanese Buddhism. Along with Ennin's posthumous title of Jikaku Daishi, this marked a new era of imperial recognition for eminent monks. Saichō continues to be revered as the founder of the Tendai school, with a major 1200th anniversary memorial service held at Enryaku-ji on June 4, 2021.

9. Influence and Legacy

Saichō's influence on Japanese Buddhism, culture, and society was profound and enduring, establishing a unique religious tradition and shaping the intellectual and spiritual landscape for centuries to come.

9.1. Impact on Japanese Buddhism

Saichō's most significant contribution was the establishment of the Japanese Tendai school, which, while rooted in Chinese Tiantai, developed a distinct identity. He articulated this uniqueness in his Naishō Buppō Sōjō Kechimyaku-fu (内証仏法相承血脈譜Naishō Buppō Sōjō Kechimyaku-fuJapanese), listing five traditions he inherited, but explicitly calling only the Tiantai Lotus school a "school" (`宗shūJapanese`). This marked a new concept of a "school" as a group united by shared doctrine, laying the groundwork for the emergence of new sectarian consciousness in Japanese Buddhism.

His emphasis on `顕密両学kenmitsu ryōgakuJapanese` (the study of both exoteric and esoteric teachings) as the ideal for Tendai monks was groundbreaking. While his initial transmission of Mikkyō was incomplete, his vision of `円密一致enmitsu itchiJapanese` (unity of perfect and esoteric teachings) became a core Tendai doctrine. Later Tendai monks, notably Ennin and Enchin, would travel to China to further deepen their understanding of Esoteric Buddhism, eventually leading to the comprehensive development of `台密TaimitsuJapanese` (Tendai Mikkyō), which was completed by Annen. Although Ennin later incorporated some aspects of Kūkai's view of Mikkyō's superiority, Saichō's original emphasis on the unity of exoteric and esoteric teachings remained foundational.

Saichō's strong advocacy for `一切衆生悉有仏性issai shujō shitsu u busshōJapanese` (all sentient beings possess Buddha-nature) and `一切皆成issai kaishōJapanese` (all can attain Buddhahood) was a crucial doctrinal contribution. By asserting that all beings, regardless of their inherent nature, could achieve Buddhahood, he offered a more inclusive and accessible path to enlightenment, directly challenging the more restrictive views of the Nara schools.

The establishment of the Mahayana ordination altar on Mount Hiei, though posthumously approved, was a revolutionary institutional reform. By allowing monks to be ordained solely under the Bodhisattva Precepts, Saichō created a unique Japanese Vinaya system, independent of the traditional Tōdai-ji ordination platform. This reform allowed for the "pure cultivation" of Mahayana monks within Japan, fostering a distinct Japanese Buddhist identity. This institutional independence and doctrinal innovation laid the essential groundwork for the flourishing of Kamakura New Buddhism in the 12th and 13th centuries, as many of its founders, including Hōnen, Shinran, Dōgen, and Nichiren, either trained on Mount Hiei or were influenced by Tendai teachings. Saichō's reforms also contributed to the later perception of Japanese Buddhism as less strict regarding monastic precepts compared to other East Asian traditions.

9.2. Cultural Contributions

Beyond his profound religious impact, Saichō also made notable contributions to Japanese culture. He is widely credited with being the first to introduce tea to Japan, bringing tea seeds back from China and planting them on Mount Hiei, which later led to the spread of tea cultivation throughout the country.

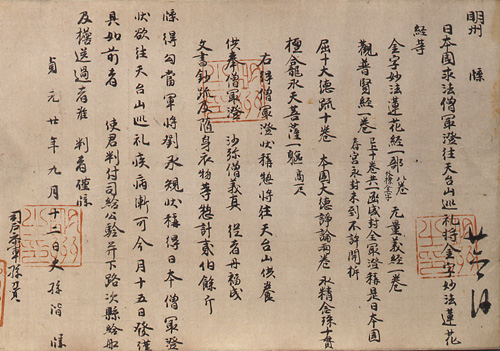

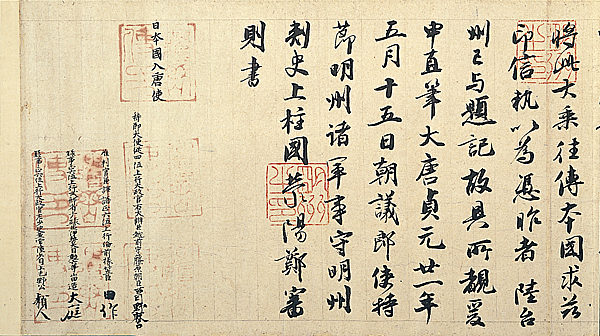

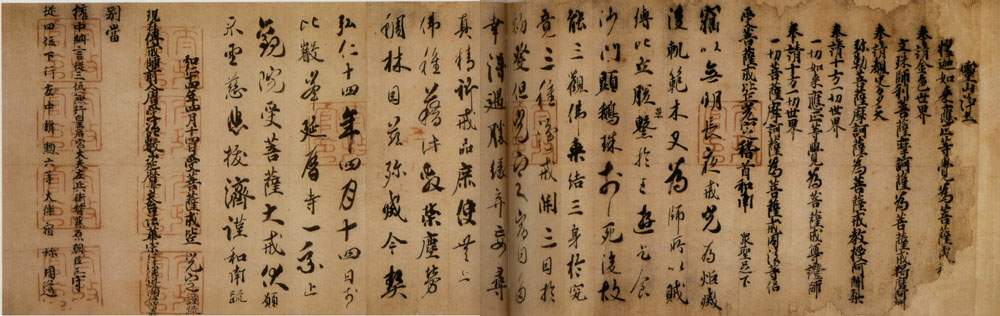

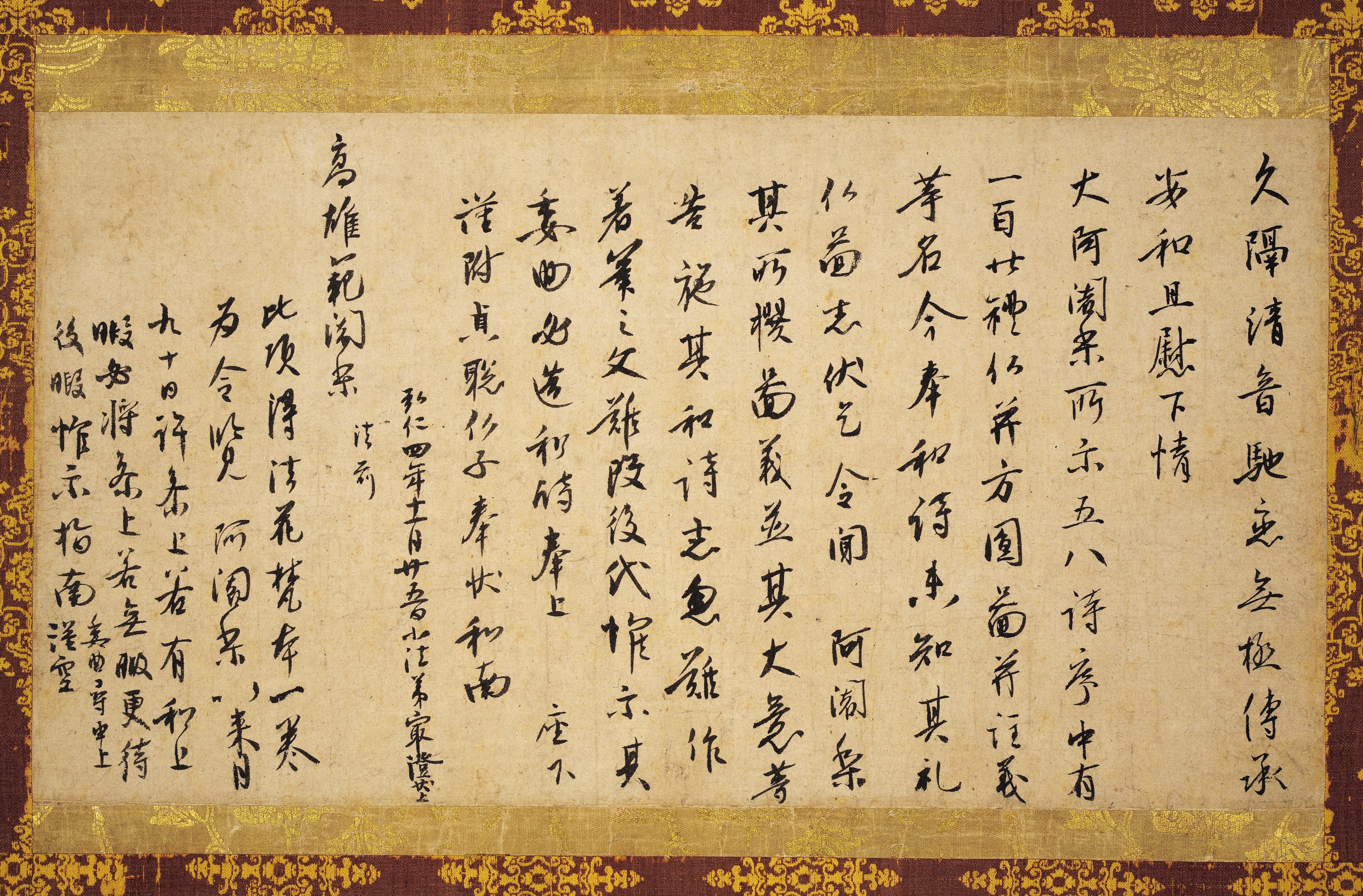

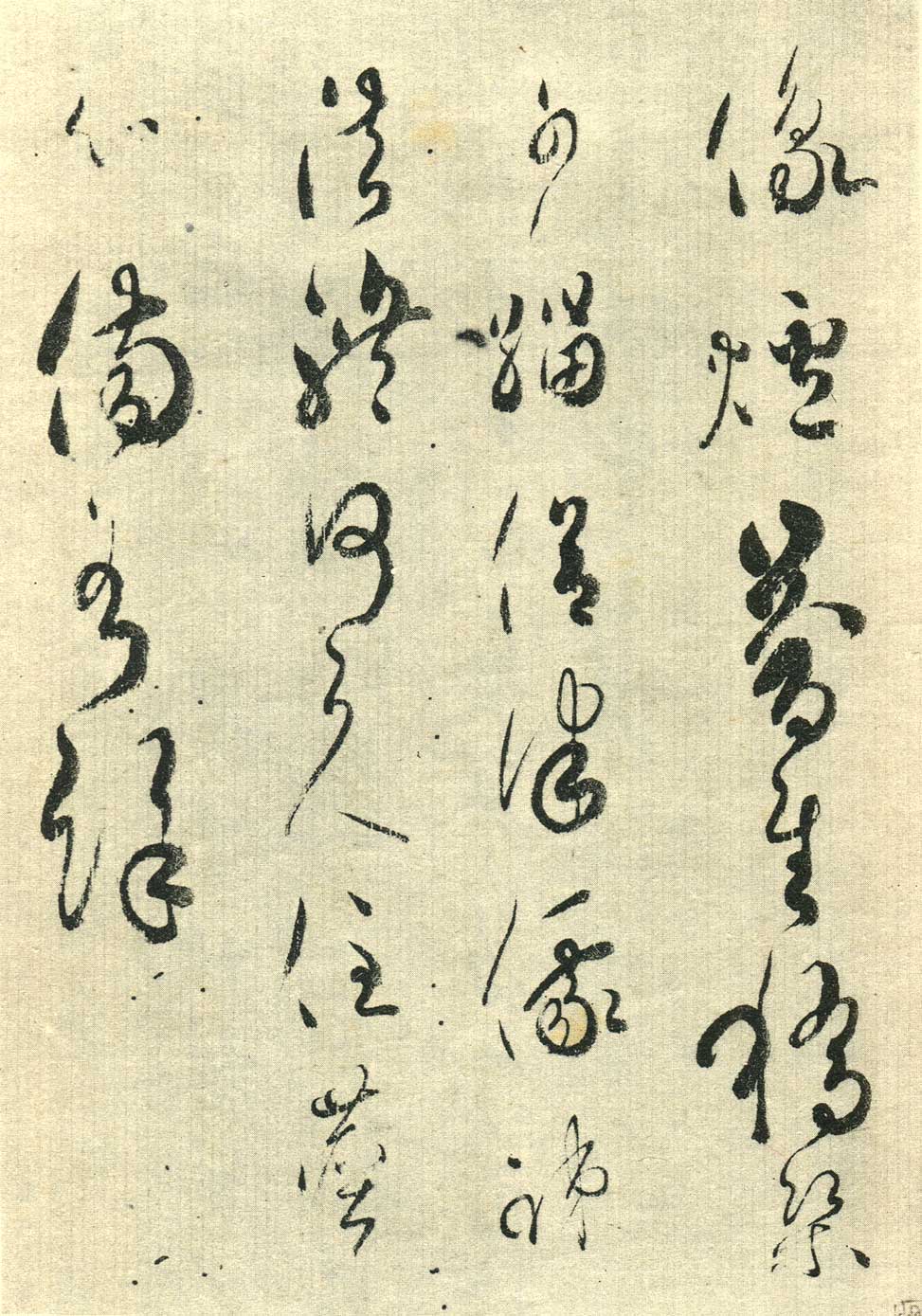

Saichō was also an accomplished calligrapher. During his trip to China, he brought back numerous calligraphic works and `法帖hōjōJapanese` (copybooks) by renowned Chinese masters such as Wang Xizhi, Wang Xianzhi, Ouyang Xun, and Chu Suiliang. His own calligraphic style is characterized by its formal, precise qualities, often compared to the `楷書kaishoJapanese` (regular script) of Wang Xizhi's Shengjiao Xu. Several of his original calligraphic works survive and are designated as National Treasures, including:

- Tendai Hokkeshū Nenbun Engi (天台法華宗年分縁起Tendai Hokkeshū Nenbun EngiJapanese): A collection of documents related to the Tendai Lotus school's annual ordinands and the establishment of the Mahayana ordination altar.

- Kyūkaku-jō (久隔帖Kyūkaku-jōJapanese): A letter written to Kūkai (addressed to his disciple Taihan) in 813, known for its elegant and dignified style.

- Esshū Shōrai Mokuroku (越州将来目録Esshū Shōrai MokurokuJapanese): A detailed catalog of the books and Mikkyō implements Saichō brought back from Yuezhou in China.

- Katsuma Kongō Mokuroku (羯磨金剛目録Katsuma Kongō MokurokuJapanese): A general catalog of items permanently stored in the sutra repository after being brought from China.

- Kūkai Shōrai Mokuroku (空海将来目録Kūkai Shōrai MokurokuJapanese): Saichō's copy of Kūkai's catalog of scriptures and texts brought from China.

Saichō also composed nine `和歌wakaJapanese` poems that are still extant. One particularly well-known poem, composed when he lit the inextinguishable lamp in the main hall on Mount Hiei, reads: "May the light of the Dharma lamp be transmitted, shining brightly until the age of future Buddhas." This poem encapsulates his enduring hope for the longevity and spread of Buddhist teachings.

Images depicting Saichō in his childhood form, known as `伝教大師童形像Dengyō Daishi DōgyōzōJapanese`, are found in numerous Tendai temples across Japan, reflecting his revered status as the school's founder.