1. Overview

Roger Joseph Ebert (June 18, 1942 - April 4, 2013) was a prominent American film critic, journalist, essayist, and author who profoundly influenced film criticism and popular culture. He served as the film critic for the Chicago Sun-Times from 1967 until his death in 2013, with his columns syndicated to over 200 newspapers internationally. In 1975, Ebert made history as the first film critic to win the Pulitzer Prize for Criticism. Alongside Gene Siskel, he revolutionized televised film reviewing through their highly popular shows, Sneak Previews and At the Movies, coining the iconic "Two Thumbs Up" phrase. Known for his accessible, humanistic writing style, Ebert championed both foreign and independent films, making sophisticated cinematic ideas understandable to a broad audience. Despite a long battle with cancer that severely impacted his physical abilities, he continued to write prolifically, expanding his online presence through RogerEbert.com and maintaining his influential voice until his passing. His legacy includes a vast body of critical work, numerous books, and a lasting impact on how films are discussed and perceived.

2. Early Life and Education

Roger Ebert's early life and educational experiences laid the foundation for his distinguished career, fostering his passion for writing and critical thought from a young age.

2.1. Childhood and Family Background

Roger Joseph Ebert was born on June 18, 1942, in Urbana, Illinois. He was the only child of Annabel (née Stumm), a bookkeeper, and Walter Harry Ebert, an electrician. His paternal grandparents were German immigrants, while his maternal ancestry was Irish and Dutch. Ebert was raised Roman Catholic, attending St. Mary's elementary school and serving as an altar boy in Urbana. He recalled his first movie memory as seeing the Marx Brothers in A Day at the Races (1937) with his parents. He cited Adventures of Huckleberry Finn as "the first real book I ever read, and still the best."

2.2. Education

Ebert's academic journey began early; he started taking classes at the University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign as an early-entrance student, completing his high school courses concurrently. He graduated from Urbana High School in 1960, where he was class president and co-editor of the high school newspaper, The Echo. In 1958, he won the Illinois High School Association state speech championship in "radio speaking," an event simulating radio newscasts.

While at the University of Illinois, he worked as a reporter for The Daily Illini and served as its editor during his senior year, continuing his work for The News-Gazette. His college mentor, Daniel Curley, introduced him to foundational literary works, shaping his appreciation for language and character. One of his first film reviews, for La Dolce Vita, was published in The Daily Illini in October 1961. After earning his undergraduate degree in journalism in 1964, Ebert pursued graduate studies in English at the University of Illinois and spent a year at the University of Cape Town on a Rotary fellowship. He then enrolled in a PhD program at the University of Chicago, where he also taught a night class on film at the Graham School of Continuing Liberal and Professional Studies starting in 1968.

2.3. Early Journalism and Writing

Ebert's writing career began with his own basement-printed newspaper, The Washington Street News. He contributed letters to science-fiction fanzines and founded his own, Stymie. At age 15, he became a sportswriter for The News-Gazette, covering Urbana High School sports. While preparing for his doctorate at the University of Chicago, he sought a job to support himself, applying to the Chicago Daily News. Instead, he was referred to the Chicago Sun-Times, where he was hired as a reporter and feature writer in 1966. In April 1967, the Sun-Times editor Robert Zonka offered him the film critic position, seeking a young voice to review contemporary films. The demands of graduate school and film criticism proved too much, leading Ebert to leave his doctoral studies to fully dedicate himself to film criticism.

3. Career as a Film Critic

Roger Ebert's career as a film critic spanned over four decades, marking him as one of the most influential voices in American journalism and popular culture. His work evolved from newspaper reviews to national television and a significant online presence, consistently shaping public discourse on cinema.

3.1. Chicago Sun-Times and Pulitzer Prize

Ebert's tenure as the film critic for the Chicago Sun-Times began on April 7, 1967, with his first review of Georges Lautner's Galia. He quickly gained prominence, influenced by film critic Pauline Kael and the philosophy of Robert Warshow, which emphasized the critic's personal, "immediate experience" of a film over theoretical frameworks. A pivotal early experience was reviewing Ingmar Bergman's Persona (1966), where he learned to describe rather than explain complex films.

He was one of the first critics to champion Arthur Penn's Bonnie and Clyde (1967), calling it "a milestone in the history of American movies, a work of truth and brilliance." He also wrote the first published review for Martin Scorsese's debut feature, Who's That Knocking at My Door (1967), predicting Scorsese could become "an American Fellini." In 1975, Ebert received the Pulitzer Prize for Criticism, becoming the first film critic to earn this prestigious award. Despite offers from The New York Times and The Washington Post, he chose to remain in Chicago.

3.2. Screenwriting

Beyond his critical work, Ebert ventured into screenwriting, notably collaborating with director Russ Meyer. He co-wrote the screenplay for Meyer's 1970 film Beyond the Valley of the Dolls, a film that was poorly received upon release but later gained cult film status. Ebert often joked about his involvement in the film. Their collaboration continued with Up! (1976) and Beneath the Valley of the Ultra-Vixens (1979). He was also involved in the unfinished Sex Pistols film Who Killed Bambi?, posting his screenplay for it on his blog in 2010.

3.3. Television Criticism

Ebert's television career transformed film criticism into a mainstream phenomenon, largely due to his dynamic partnership with Gene Siskel.

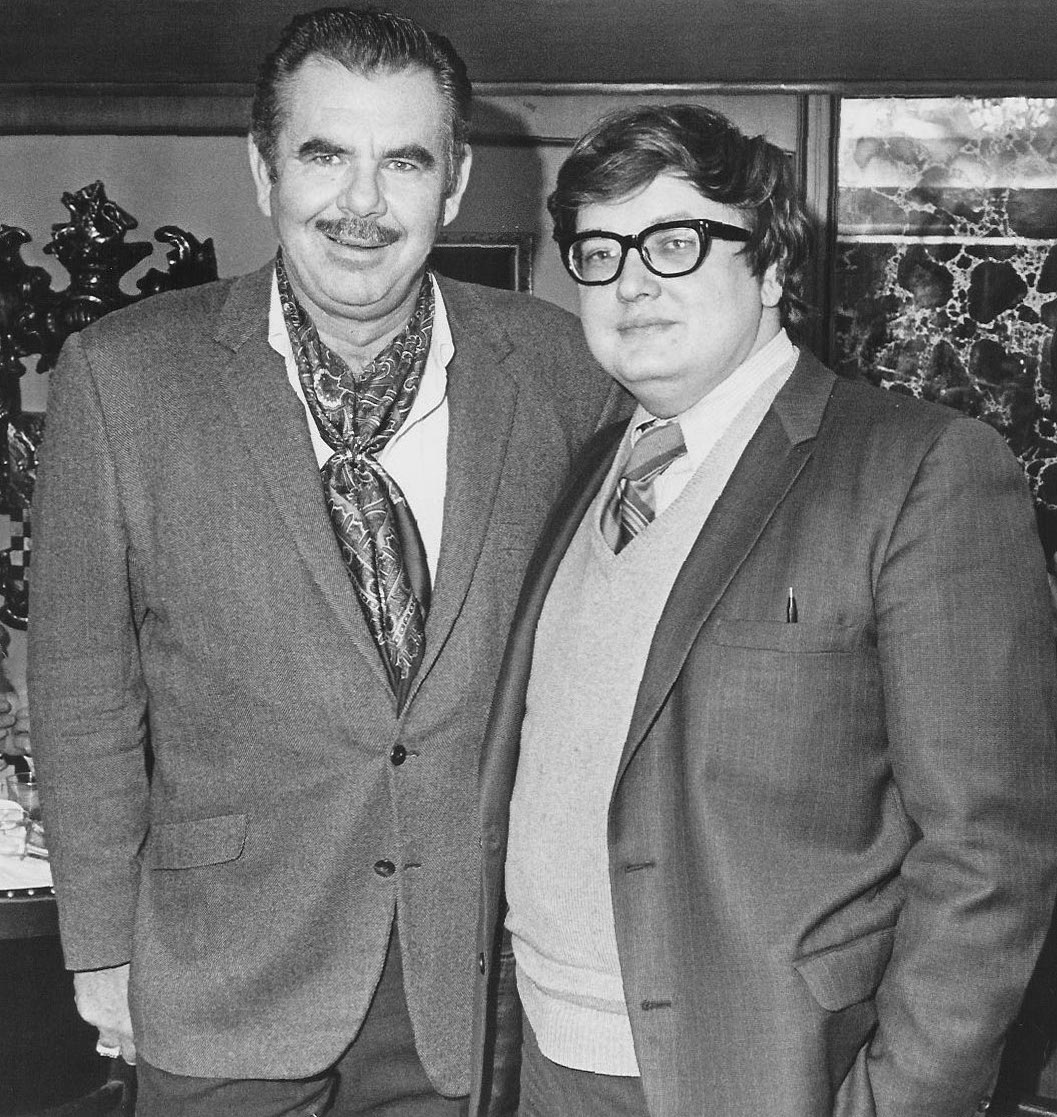

3.3.1. Sneak Previews and At the Movies (with Gene Siskel)

In 1975, Ebert partnered with Chicago Tribune critic Gene Siskel to co-host a weekly film-review television show, initially titled Opening Soon at a Theater Near You, later renamed Sneak Previews. Produced by Chicago's public broadcasting station WTTW, the show gained national syndication on PBS. The duo became famous for their on-screen chemistry, characterized by verbal sparring and humorous barbs while discussing films. They created and trademarked the iconic phrase "Two Thumbs Up," used when both critics gave a film a positive review. Their popularity led to numerous appearances on late-night talk shows, including The Late Show with David Letterman and The Tonight Show Starring Johnny Carson.

In 1982, Siskel and Ebert moved to commercial television, launching At the Movies With Gene Siskel & Roger Ebert. In 1986, they transitioned again to Buena Vista Television, part of the Walt Disney Company, creating Siskel & Ebert & the Movies. While some critics accused them of trivializing film criticism, Ebert argued that their show served to "light a bulb" for young viewers, encouraging them to form their own opinions and addressing important cinematic issues like colorization and letterboxing.

3.3.2. Siskel & Ebert & the Movies

The show continued under the title Siskel & Ebert & the Movies with their established format. Their on-screen debates and contrasting opinions became a hallmark of the program. Ebert fondly recalled his colleague, stating, "For the first five years that we knew one another, Gene Siskel and I hardly spoke. Then it seemed like we never stopped." He admired Siskel's work ethic and dedication to film criticism, even during his illness. Siskel's signature question, "What do you know for sure?", became a memorable part of their dynamic. Ebert later reflected on their relationship, describing it as a "love/hate" bond where "the hate" was "meaningless" and "the love" was "deep."

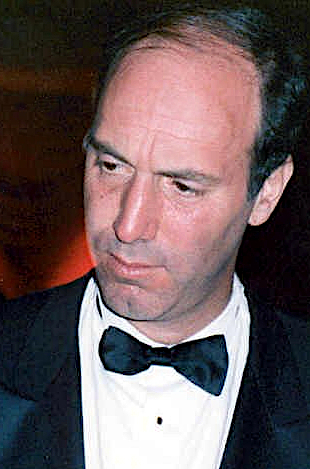

3.3.3. Ebert & Roeper

After Gene Siskel's death from a brain tumor in February 1999, the show was temporarily renamed Roger Ebert & the Movies, featuring rotating co-hosts such as Martin Scorsese, Janet Maslin, and A.O. Scott. In September 2000, Chicago Sun-Times columnist Richard Roeper became the permanent co-host, and the show was renamed At the Movies with Ebert & Roeper, later shortened to Ebert & Roeper. In 2000, Ebert interviewed President Bill Clinton about movies at The White House.

In 2002, Ebert was diagnosed with cancer of the salivary glands. Subsequent surgeries in 2006, including a mandibulectomy that removed a section of his lower jaw, left him unable to speak or eat normally. Despite these severe physical challenges, Ebert remained committed to his work. He posted a picture of his changed appearance in 2007, humorously paraphrasing a line from Raging Bull (1980): "I ain't a pretty boy no more." He continued to review films, often communicating through his wife, Chaz. Ebert ended his association with At The Movies in July 2008, as Disney sought to take the program in a new direction.

3.3.4. Ebert Presents: At the Movies

Despite his health challenges, Ebert continued his television ventures. His final television series, Ebert Presents: At the Movies, premiered on January 21, 2011. In this show, Ebert contributed reviews voiced by Bill Kurtis in a segment called "Roger's Office," alongside traditional film reviews by Christy Lemire and Ignatiy Vishnevetsky. The program ran for one season before being canceled due to funding constraints.

3.4. RogerEbert.com and Online Presence

Ebert's online presence became increasingly significant, especially after his health issues affected his ability to speak. His website, RogerEbert.com, launched in 2002 and initially underwritten by the Chicago Sun-Times, served as a comprehensive archive of his published writings and reviews. It also became a platform for his prolific blogging, where he shared his thoughts on various topics beyond film, connecting directly with a wider audience. Peter Debruge noted that "Ebert was one of the first writers to recognize the potential of discussing film online." The website continues to operate as an archive and publishes new material from a team of critics personally selected by Ebert before his death. He continued to write for the Chicago Sun-Times and maintain his online presence until his passing in 2013.

3.5. The Great Movies Series

In 1996, Ebert embarked on a significant project: publishing essays on "great movies of the past." This initiative, proposed to the Chicago Sun-Times, resulted in a biweekly series of longer articles. The first film he wrote about for this series was Casablanca (1942). One hundred of these essays were compiled and published as The Great Movies in 2002. He subsequently released two more volumes, The Great Movies II (2005) and The Great Movies III (2010), with a fourth volume, The Great Movies IV, published posthumously in 2016. This series showcased Ebert's deep knowledge of film history and his ability to revisit and refine his opinions over time, as exemplified by his re-evaluation of films like The Godfather Part II and Blade Runner. He often reflected on how his own life experiences changed his perception of these films, such as with La Dolce Vita, which he viewed differently at various stages of his life.

3.6. Ebertfest (Overlooked Film Festival)

In 1999, Ebert founded The Overlooked Film Festival, later renamed Ebertfest, in his hometown of Champaign, Illinois. This annual film festival was dedicated to showcasing films that he believed were overlooked by mainstream audiences or critics. The festival provided a platform for independent, foreign, and artistically significant films that might not otherwise receive wide recognition. Ebert actively curated the festival, and even after losing his voice, he continued to participate, communicating through his wife, Chaz, and a computerized voice system.

4. Critical Style and Philosophy

Roger Ebert's critical style was characterized by its accessibility, intellectual depth, and a distinctive blend of personal insight and objective analysis. His philosophy centered on the idea that film criticism should engage readers and illuminate the art of cinema.

4.1. Influences and Approach

Ebert cited Andrew Sarris and Pauline Kael as key influences on his critical approach. He frequently quoted Robert Warshow's assertion: "A man goes to the movies. A critic must be honest enough to admit he is that man." Ebert's personal credo was, "Your intellect may be confused, but your emotions never lie to you." He aimed to judge a movie based on its style rather than its content, often stating, "It's not what a movie is about, it's how it's about what it's about." He believed that a good critic should set aside theory and ideology to embrace the immediate experience of a film.

4.2. Writing Style and Use of Anecdotes

Ebert's writing was renowned for its plain-spoken, Midwestern clarity and genial, conversational tone, making complex cinematic and analytical ideas accessible to non-specialist audiences. He rarely wasted time, often smuggling plot basics into a larger thesis about the film. His prose, praised by A.O. Scott of The New York Times, showed a formidable intellectual range without appearing boastful.

He frequently incorporated personal anecdotes into his reviews, connecting films to his own life experiences. For instance, in his review of The Last Picture Show, he reminisced about his childhood moviegoing experiences. When reviewing Star Wars, he described having an "out-of-the-body experience," where his imagination felt part of the film's events. Ebert also experimented with various forms, writing reviews as stories, poems, songs, scripts, open letters, or imagined conversations, showcasing his dry wit and versatility. His negative reviews were particularly memorable for their cutting sarcasm and vivid descriptions, such as his infamous zero-star review of North, where he famously wrote, "I hated this movie. Hated hated hated hated hated this movie. Hated it."

4.3. Star Ratings and Review Structure

Ebert employed a four-star rating system, with four stars indicating the highest quality and generally a half-star for the lowest. However, he reserved no stars for films he deemed "artistically inept and morally repugnant," like Death Wish II. He emphasized that his star ratings held little meaning outside the context of the full review, explaining that ratings were relative to a film's genre and audience expectations. For example, a three-star rating for Hellboy meant it was good within its genre, not compared to a drama like Mystic River. He acknowledged that he tended to give higher ratings on average than other critics, partly because his "thumbs up" threshold was typically three out of four stars.

4.4. Views on Genres and Content

Ebert's critical philosophy extended to his views on diverse film genres and controversial content, advocating for quality and artistic merit across the board.

4.4.1. Animation and Documentaries

Ebert was a strong advocate for animation, particularly championing the films of Hayao Miyazaki and Isao Takahata. He believed animation offered "wondrous sights not available in the real world" and could "create a new existence in their own right," freeing storytelling from the constraints of reality. He frequently challenged the notion that animated films were "just for children," insisting on their artistic merit for all ages.

He also championed documentaries, recognizing their power to illuminate human lives and societal issues. He praised films like Errol Morris's Gates of Heaven for its depth and complexity, and Michael Apted's Up series for its "inspired, even noble use of the medium." Ebert considered Hoop Dreams one of the "great moviegoing experiences" of his lifetime, highlighting its blend of poetry, prose, and journalism.

4.4.2. Foreign and Independent Films

Ebert played a crucial role in bringing international and independent cinema to wider American audiences. He endorsed films he believed mainstream viewers would appreciate, championing filmmakers such as Werner Herzog, Errol Morris, and Spike Lee. He lamented the decline of campus film societies and repertory theaters, which he believed had limited young people's exposure to classic works by masters like Luis Buñuel, Federico Fellini, Ingmar Bergman, and Akira Kurosawa. He credited the Hawaii International Film Festival and film historian Donald Richie for introducing him to Asian cinema, frequently attending the festival to support its status.

4.4.3. Specific Genres and Themes

Ebert appreciated the aesthetic values of black-and-white photography, arguing against colorization. He believed black-and-white films created a "mysterious dream state," emphasizing shapes, forms, and light, making them more "dreamlike, more pure" than color films. He found that black-and-white photography imbued subjects with "an aura of mystery."

He did not believe in grading children's movies on a curve, asserting that children are intelligent and deserve quality entertainment. His review of Willy Wonka & the Chocolate Factory exemplified this, where he praised it as the best of its kind since The Wizard of Oz, while criticizing most children's films for being "stupid, witless and display contempt for their audiences."

Ebert was often critical of the Motion Picture Association of America film rating system (MPAA), arguing it was too strict on sex and profanity but too lenient on violence. He found their guidelines secretive, inconsistent, and lacking consideration for a film's broader context. He advocated for replacing the NC-17 rating with separate categories for pornographic and non-pornographic adult films.

He generally preferred a "generic approach" to film criticism, asking "how good a movie is of its type." This allowed him to give a four-star review to Halloween, acknowledging its effectiveness as a horror thriller. While he used his Catholic upbringing as a point of reference in his reviews, he tried not to judge films solely on their ideology. He was critical of films he believed were grossly ignorant or insulting to Catholicism, such as Stigmata (1999) and Priest (1994), yet he gave favorable reviews to controversial films like The Last Temptation of Christ (1988) and Kevin Smith's religious satire Dogma (1999). He also defended Spike Lee's Do the Right Thing, emphasizing its fairness to all characters and its commentary on societal injustice.

4.5. Relationships with Filmmakers

Ebert maintained significant relationships, both supportive and contentious, with various filmmakers throughout his career. He wrote Martin Scorsese's first review for Who's That Knocking at My Door and later praised Scorsese as the best director to emerge during his career, noting his active camera work and ability to convey states of mind. In 2000, Scorsese joined Ebert on his show to select the best films of the 1990s.

Ebert was a profound admirer of Werner Herzog, often quoting Herzog's belief that "our civilization is starving for new images." Herzog dedicated his film Encounters at the End of the World to Ebert, who responded with an open letter of gratitude. In 2010, Ebert and Herzog jointly analyzed Aguirre, the Wrath of God at the Conference on World Affairs.

He was also known for his public clashes with filmmakers. When he called Vincent Gallo's The Brown Bunny (2003) the worst film in Cannes history, Gallo responded with a curse. Ebert famously retorted, "I had a colonoscopy once, and they let me watch it on TV. It was more entertaining than The Brown Bunny." He later gave a positive review to the director's cut, acknowledging Gallo's improved editing. Another notable exchange occurred with Rob Schneider, who criticized a Los Angeles Times critic for not having a Pulitzer Prize. Ebert, a Pulitzer winner, responded directly to Schneider's film Deuce Bigalow: European Gigolo with the memorable line, "Mr. Schneider, your movie sucks." Despite the sharp criticism, Schneider later sent Ebert flowers after his cancer surgery, to which Ebert responded with grace, acknowledging Schneider's good intentions.

4.6. Contrarian Reviews

Ebert's critical opinions sometimes diverged significantly from mainstream consensus, leading to notable "contrarian reviews." While he acknowledged giving higher ratings on average than other critics (partly because three out of four stars was his "thumbs up" threshold), he was not deliberately provocative.

Examples of his dissenting negative reviews include his critiques of acclaimed films like Blue Velvet (which he found "marred by sophomoric satire"), A Clockwork Orange (calling it "a paranoid right-wing fantasy"), and The Usual Suspects ("To the degree that I do understand, I don't care"). He gave only two out of four stars to the widely acclaimed Brazil, finding it "very hard to follow," and was the sole critic on Rotten Tomatoes to dislike it. He also gave a one-star review to Abbas Kiarostami's Taste of Cherry, which won the Palme d'Or at the 1997 Cannes Film Festival, later adding it to his list of most-hated movies. He was dismissive of the 1988 action film Die Hard, stating that "inappropriate and wrongheaded interruptions reveal the fragile nature of the plot."

Conversely, some of his positive reviews were outliers. His three-star review of 1997's Speed 2: Cruise Control, in which he praised its "goofiness," stood out as one of only three positive reviews for the film on Rotten Tomatoes (the other two being from Gene Siskel). Ebert defended this review, appreciating films that showed him something new, such as a cruise ship plowing through a Caribbean village. In 1999, he even held a contest for students to create short films with a Speed 3 theme, screening the winning entry at Ebertfest.

5. Other Interests and Activities

Beyond his primary role as a film critic, Roger Ebert engaged with a wide array of subjects, demonstrating his expansive intellectual curiosity and commitment to various forms of communication.

5.1. Writing Beyond Film Criticism

Ebert was a prolific writer whose output extended far beyond film reviews. He authored numerous books covering diverse topics. His earliest book, An Illini Century: One Hundred Years of Campus Life (1967), chronicled the history of the University of Illinois. He explored travel in The Perfect London Walk (1986), co-authored with Daniel Curley, and Two Weeks In Midday Sun: A Cannes Notebook (1987), detailing his experiences at the Cannes Film Festival. He also delved into fiction with Behind the Phantom's Mask (1993), his only work of its kind. His book The Pot and How to Use It: The Mystery and Romance of the Rice Cooker (2010) showcased his interest in cooking.

He compiled collections of his writings, including Awake in the Dark: The Best of Roger Ebert (2006), a retrospective of his 40 years as a critic, and Questions for the Movie Answer Man (1997), compiling his responses to reader inquiries. His memoir, Life Itself (2011), offered a personal account of his childhood, career, and struggles with alcoholism and cancer. He also published collections of his least favorite reviews, such as I Hated, Hated, Hated This Movie (2000), Your Movie Sucks (2007), and A Horrible Experience of Unbearable Length (2012), titles derived from his famously scathing reviews.

Ebert was a lifelong reader, owning nearly every book he had since age seven. He considered authors like Shakespeare, Henry James, Willa Cather, Colette, and Georges Simenon indispensable. He admired Cormac McCarthy, crediting Suttree with rekindling his love of reading after his illness. He also enjoyed audiobooks and was a fan of Hergé's The Adventures of Tintin, which he read in French.

5.2. Views on Technology

Ebert held strong opinions on technological advancements in filmmaking. He was a vocal advocate for Maxivision 48, a projection format that runs at 48 frames per second, double the standard 24 frames per second, believing it enhanced the viewing experience. He opposed the practice of theaters dimming projector bulbs to extend their life, arguing it compromised film visibility. However, he was skeptical of the resurgence of 3D effects, finding them unrealistic and distracting.

5.3. Views on Video Games as Art

Ebert's stance on video games as an art form sparked considerable debate. In 2005, he opined that video games were not art, stating that "the nature of the medium prevents it from moving beyond craftsmanship to the stature of art." He argued that art is created by an artist, and if the audience changes it, they become the artist, likening video games more to sports than art. This position drew significant criticism from video game enthusiasts and figures like writer Clive Barker, who defended the artistic merits of games.

Ebert maintained his position in 2010, but conceded that he should not have expressed such skepticism without being more familiar with the actual experience of playing them. He admitted to having played very few video games, though he did enjoy Cosmology of Kyoto and found Myst lacked his patience. He acknowledged that "It is quite possible a game could someday be great art." Earlier, in 1994, he had reviewed Cosmology of Kyoto for Wired, praising its exploration, depth, and graphics as "the most beguiling computer game I have encountered." He also wrote another article for Wired in 1994, describing his visit to Sega's Joypolis arcade in Tokyo.

6. Personal Life

Roger Ebert's personal life was marked by a loving marriage, a significant journey of recovery, and a resilient battle with illness, all while maintaining a strong public voice on social and political issues.

6.1. Marriage and Family

At age 50, Roger Ebert married trial attorney Charlie "Chaz" Hammel-Smith in 1992. Chaz Ebert became a central figure in his life and career, serving as vice president of the Ebert Company and emceeing Ebertfest. In his memoir, Life Itself, Ebert explained that he had delayed marriage until after his mother's passing, fearing her disapproval. He wrote movingly about Chaz in a 2012 blog entry: "She fills my horizon, she is the great fact of my life, she has my love, she saved me from the fate of living out my life alone, which is where I seemed to be heading... She has been with me in sickness and in health, certainly far more sickness than we could have anticipated. I will be with her, strengthened by her example. She continues to make my life possible, and her presence fills me with love and a deep security. That's what a marriage is for. Now I know."

6.2. Alcoholism Recovery

Ebert was a recovering alcoholic, having achieved sobriety in 1979. He was a member of Alcoholics Anonymous and openly discussed his journey in blog entries. He was a longtime friend of Oprah Winfrey, who credited him with persuading her to syndicate The Oprah Winfrey Show, which went on to become the highest-rated talk show in American television history.

6.3. Health and Battle with Cancer

In February 2002, Ebert was diagnosed with papillary thyroid cancer, which was successfully removed. In 2003, he underwent surgery for salivary gland cancer, followed by radiation therapy. His cancer recurred in 2006, leading to a mandibulectomy in June of that year to remove cancerous tissue from his lower jaw. A week later, he experienced a life-threatening complication when his carotid artery burst near the surgery site. This necessitated bed rest and left him unable to speak, eat, or drink normally, requiring a feeding tube.

These complications kept Ebert off the air for an extended period. He made his first public appearance since mid-2006 at Ebertfest on April 25, 2007, communicating through his wife. He resumed writing reviews on May 18, 2007, but remained unable to speak. Ebert eventually adopted a computerized voice system for communication, later using a synthesized voice created from his own recordings by CereProc. His health struggles and new voice were featured on The Oprah Winfrey Show in March 2010. In 2011, he delivered a TED talk titled "Remaking my voice," where he proposed a test to determine the verisimilitude of a synthesized voice.

He underwent further surgeries in January and April 2008 to try and restore his voice and address complications, including a fractured hip from a fall. By 2011, Ebert used a prosthetic chin to conceal some of the disfigurement from his many surgeries. In December 2012, he was hospitalized again due to a fractured hip, which was later determined to be the result of cancer.

Ebert often reflected on the profound impact of his inability to eat and speak: "The loss of dining, not the loss of food. It may be personal, but for me, unless I'm alone, it doesn't involve dinner if it doesn't involve talking. The food and drink I can do without easily. The jokes, gossip, laughs, arguments and shared memories I miss." He found solace in his blog, where he felt he could still engage in conversation.

6.4. Political and Religious Beliefs

Ebert was a staunch supporter of the Democratic Party, and his political views were deeply rooted in his Catholic schooling. He believed the nuns who educated him guided him towards supporting universal health care, labor unions, fair taxation, prudence in warfare, kindness, and equal opportunity for all races and genders. He expressed surprise that many who considered themselves religious often held opposing views.

He was critical of political correctness, viewing it as a rigid mindset that stifled challenging ideas and boundary-breaking criticism and art. He defended the right of Asian-American filmmakers to create diverse characters without having to represent "their people," famously confronting an audience member at the Sundance Film Festival who questioned the "amoral" nature of Justin Lin's Better Luck Tomorrow (2002).

Ebert opposed the Iraq War, stating, "Am I against the war? Of course. Do I support our troops? Of course. They were sent to endanger their lives by zealots with occult objectives." He endorsed Barack Obama for re-election in 2012, citing the Affordable Care Act as a key reason. He was concerned about income inequality, criticizing financial scams and the manipulation of financial instruments that led to the subprime mortgage crisis. He voiced tentative support for the Occupy Wall Street movement, believing it opposed "lawless and destructive greed in the financial industry." He also expressed sympathy for Ron Paul, praising his direct and clear communication, and credited Paul with being a "lonely voice" on the national debt. Ebert opposed the war on drugs and capital punishment. His Chicago Sun-Times editor, Laura Emerick, noted his lifelong commitment to the Newspaper Guild, even as an independent contractor, demonstrating his strong union sympathies. He emphasized the importance of freedom of speech and the citizen's responsibility to speak out.

Ebert was critical of intelligent design and stated that proponents of creationism or New Age beliefs like crystal healing or astrology should not be president. He found the Theory of Evolution to be a "pillar of my reasoning," explaining many things and opening a window into arts and literature. While he sometimes described himself as an agnostic, he also rejected this categorization, stating he didn't want his convictions "reduced to a word." He described himself as "not a believer, not an atheist, not an agnostic," but rather someone "still awake at night, asking how?" He found contentment in the question itself rather than a definitive answer, worshiping "the void" and "the mystery." He believed that the purpose of life was to "contribute joy to the world," and that "To make others less happy is a crime. To make ourselves unhappy is where all crime starts." He found solace in the words of Brendan Behan, who valued kindness above all else.

7. Death and Legacy

Roger Ebert's death marked the end of an era in film criticism, but his influence and legacy continue to resonate deeply within the industry and popular culture.

7.1. Death

On April 4, 2013, Roger Ebert died at age 70 at a hospital in Chicago. His passing occurred shortly before he was scheduled to return home and enter hospice care, following an 11-year battle with cancer.

7.2. Tributes and Memorials

Ebert's death prompted a widespread outpouring of tributes from public figures, filmmakers, critics, and fans. President Barack Obama stated that "For a generation of Americans - and especially Chicagoans - Roger was the movies," praising his ability to capture "the unique power of the movies to take us somewhere magical." Martin Scorsese described Ebert's death as "an incalculable loss for movie culture and for film criticism," calling him a personal friend. Steven Spielberg highlighted Ebert's deep knowledge of film and history, noting that he "put television criticism on the map." Numerous celebrities, including Christopher Nolan, Oprah Winfrey, Steve Martin, and Werner Herzog, also paid tribute.

Michael Phillips of the Chicago Tribune remembered Ebert as a "theatrical personality" who made room for others in his "outsized life." Andrew O'Hehir of Salon likened him to great American commentators like Mark Twain. Richard Corliss of Time praised Ebert as an "apostle of cinema" who connected creators with consumers and continually discovered things to share, like a great teacher. The Onion published a satirical tribute, where Ebert "praised existence as 'an audacious and thrilling triumph.'"

A nearly-three-hour public tribute, Roger Ebert: A Celebration of Life, was held on April 11, 2013, at the Chicago Theatre, featuring remembrances, video testimonials, and gospel choirs. His funeral Mass was held at Chicago's Holy Name Cathedral on April 8, 2013, where he was celebrated as a critic, newspaperman, social justice advocate, and husband. Father Michael Pfleger concluded the service with "the balconies of heaven are filled with angels singing 'Thumbs Up'." Ebert was buried at Graceland Cemetery in Chicago, Illinois.

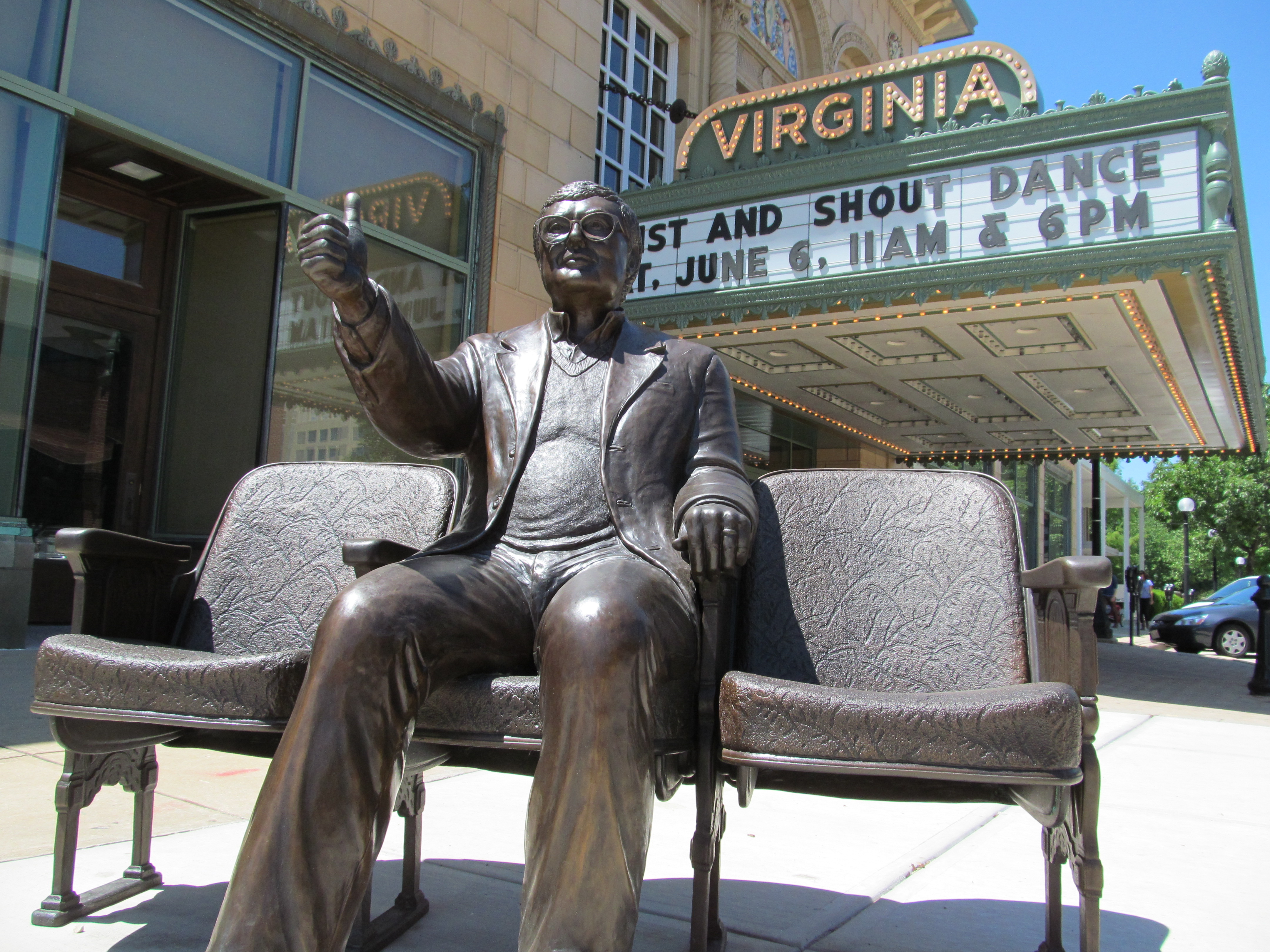

In September 2013, plans were announced to build a life-size bronze statue of Roger Ebert in Champaign, Illinois. Unveiled at Ebertfest on April 24, 2014, the statue, selected by his widow Chaz, depicts Ebert giving a "thumbs up" from a theater seat. The 2013 Toronto International Film Festival opened with a video tribute to Ebert, a long-time supporter of the festival. Errol Morris dedicated his film The Unknown Known to Ebert at the same festival. The Plaza Classic Film Festival in El Paso, Texas, also paid homage by screening seven films significant to Ebert's life. At the 86th Academy Awards ceremony, Ebert was included in the in memoriam montage, a rare honor for a film critic.

7.3. Enduring Influence

Ebert's enduring influence stems from his ability to engage a broad audience, his advocacy for diverse cinema, and his commitment to critical discourse. His negative reviews, while entertaining, aimed to enlighten readers and challenge them to think, while his positive reviews championed films that might otherwise be overlooked. Werner Herzog described Ebert as "a soldier of the cinema," who tirelessly promoted intelligent discourse about film.

In 2014, the documentary Life Itself, directed by Steve James and executive produced by Martin Scorsese, was released. The film chronicled Ebert's life and career, including his final months, and received widespread critical acclaim.

Ebert was inducted as a laureate of The Lincoln Academy of Illinois, receiving the state's highest honor, the Order of Lincoln, in 2001. In 2016, he was inducted into the Chicago Literary Hall of Fame. His website, RogerEbert.com, continues to serve as a comprehensive archive of his work and publishes new material from a team of critics he personally selected, ensuring his critical voice and legacy persist.

8. Awards and Honors

Roger Ebert received numerous awards and honors throughout his distinguished career, recognizing his groundbreaking contributions to film criticism and journalism.

- 1975**: Pulitzer Prize for Criticism, becoming the first film critic to win this award for his work at the Chicago Sun-Times.

- 1995**: Publicists Guild of America Press Award.

- 2001**: Order of Lincoln, Illinois' highest honor, in the area of performing arts.

- 2003**: American Society of Cinematographers' Special Achievement Award.

- 2004**: Savannah Film Festival's Lifetime Achievement Award.

- 2005**: Became the first film critic to receive a star on the Hollywood Walk of Fame, located at 6834 Hollywood Boulevard.

- 2007**: Gotham Awards tribute and award for his lifetime contributions to independent film.

- 2009**: Directors Guild of America Award's Honorary Life Member Award.

- 2009**: The American Pavilion at the Cannes Film Festival renamed its conference room "The Roger Ebert Conference Center."

- 2010**: Webby Award for Person of the Year, recognizing his influential online presence after his health challenges.

- 2016**: Inducted into the Chicago Literary Hall of Fame.

Ebert's television shows also received recognition:

| Year | Award | Category | Nominated work | Result |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1979 | Chicago Emmy Awards | Outstanding Special Program | Sneak Previews | - |

| 1984 | Primetime Emmy Award | Outstanding Informational Series | At the Movies | - |

| 1985 | - | |||

| 1987 | Siskel & Ebert & the Movies | - | ||

| 1988 | - | |||

| 1989 | Daytime Emmy Awards | Outstanding Special Class Program | - | |

| 1990 | - | |||

| 1991 | - | |||

| 1992 | Primetime Emmy Awards | Outstanding Informational Series | - | |

| 1994 | - | |||

| 1997 | - | |||

| 2005 | Chicago Emmy Awards | Silver Circle Award | - | - |

9. Published Works

Roger Ebert was a prolific author, publishing numerous books throughout his career, including annual film yearbooks and comprehensive collections of his reviews and essays.

9.1. Major Books

- An Illini Century: One Hundred Years of Campus Life (1967) - A history of the first 100 years of the University of Illinois.

- A Kiss Is Still a Kiss (1984)

- The Perfect London Walk (1986), with Daniel Curley - A tour of London, Ebert's favorite foreign city.

- Two Weeks In Midday Sun: A Cannes Notebook (1987) - Coverage of the 1987 Cannes Film Festival, including comments on previous festivals and interviews.

- The Future of The Movies (1991), with Gene Siskel - Collected interviews with Martin Scorsese, Steven Spielberg, and George Lucas on the future of motion pictures and film preservation; the only book co-authored by Siskel and Ebert.

- Behind the Phantom's Mask (1993) - Ebert's only work of fiction, a story about an on-stage murder.

- Ebert's Little Movie Glossary (1994) - A book of movie clichés.

- Roger Ebert's Book of Film (1996) - A comprehensive anthology of a century of writing about movies.

- Questions for the Movie Answer Man (1997) - His responses to questions from his readers.

- Ebert's Bigger Little Movie Glossary (1999) - A greatly expanded version of his movie clichés book.

- I Hated, Hated, Hated This Movie (2000) - A collection of his reviews for films that received two stars or fewer, dating to the beginning of his Sun-Times career. The title is from his zero-star review of North.

- Awake in the Dark: The Best of Roger Ebert (2006) - A collection of essays from his 40 years as a film critic, featuring interviews, profiles, essays, initial reviews, and critical exchanges with other film critics.

- Your Movie Sucks (2007) - A collection of fewer-than-two-star reviews for movies released between 2000 and 2006. The title is from his zero-star review of Deuce Bigalow: European Gigolo.

- Roger Ebert's Four-Star Reviews 1967-2007 (2007).

- Scorsese by Ebert (2008) - Covers works by director Martin Scorsese from 1967 to 2008, including 11 interviews with the director.

- The Pot and How to Use It: The Mystery and Romance of the Rice Cooker (2010).

- Life Itself: A Memoir (2011) - His autobiography.

- A Horrible Experience of Unbearable Length (2012) - A third book of fewer-than-two-star reviews, for movies released from 2006 onward. The title is from his one-star review of Transformers: Revenge of the Fallen.

9.2. Film Yearbooks and Essay Collections

From 1986 to 1998, Ebert published Roger Ebert's Movie Home Companion (later Roger Ebert's Video Companion), which compiled all of his movie reviews up to that point. From 1999 to 2013 (except 2008), he published Roger Ebert's Movie Yearbook, a collection of his film reviews from the previous two and a half years, along with yearly essays and interviews.

His most notable essay collection series is The Great Movies, which includes:

- The Great Movies (2002)

- The Great Movies II (2005)

- The Great Movies III (2010)

- The Great Movies IV (2016, posthumously published)

These volumes comprise essays on films he considered "great," reflecting his deep critical analysis and evolving perspectives on cinema.