1. Overview

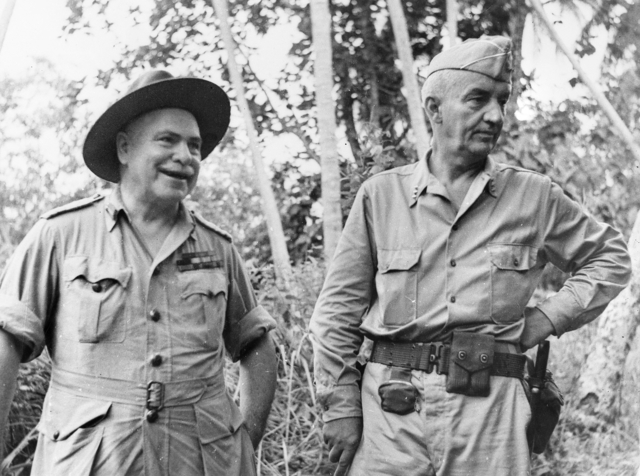

Robert Lawrence Eichelberger (March 9, 1886 - September 26, 1961) was a distinguished general officer in the United States Army who played a pivotal role in World War II and the subsequent Occupation of Japan. A 1909 graduate of the United States Military Academy at West Point, his early career included service in Panama and on the Mexican border before his significant involvement in the American Expeditionary Force Siberia during the Russian Civil War, where he earned the Distinguished Service Cross for repeated acts of bravery.

During World War II, Eichelberger commanded the Eighth United States Army in the Southwest Pacific Area, leading crucial campaigns such as the Battle of Buna-Gona in New Guinea and major operations in the Philippines, including Leyte and Luzon. His leadership was characterized by a direct, often demanding, approach to combat, particularly in challenging jungle warfare environments. Following the war, his Eighth Army spearheaded the Allied occupation of Japan, where he served as the second-highest ranking official under Douglas MacArthur. In this role, he engaged with the Japanese government, advocated for Japanese rearmament, and contributed to the establishment of the Maritime Safety Agency, influencing Japan's post-war security policy, notably through the "Ashida Memo" which laid a foundation for the Japan-US Security Treaty. While publicly maintaining a professional relationship with MacArthur, Eichelberger's private papers reveal scathing criticisms of his superior, offering a complex view of their dynamic. He retired from the Army in 1948 and was posthumously promoted to general in 1954, leaving a notable legacy in military history and international relations.

2. Early Life and Education

Robert Lawrence Eichelberger's early life and education laid the foundation for his extensive military career, marked by a challenging academic journey and early exposure to military service.

2.1. Childhood and Education

Robert Lawrence Eichelberger was born in Urbana, Ohio, on March 9, 1886, the youngest of five children to George Maley Eichelberger, a farmer and lawyer, and Emma Ring Eichelberger. He grew up on the family farm, which spanned 235 acre (235 acre) and had been established by his grandfather. He completed his high school education at Urbana High School in 1903. Following high school, he enrolled at Ohio State University, where he became a member of the Phi Gamma Delta fraternity.

In 1904, Eichelberger secured an appointment to the United States Military Academy at West Point through his father's former law partner, William R. Warnock, who was then the congressman for Ohio's 8th congressional district. He entered West Point in June 1905 as part of the distinguished class of 1909, which included 28 future general officers such as Jacob L. Devers, John C. H. Lee, Edwin F. Harding, George S. Patton, and William H. Simpson. Despite being a self-described poor student throughout high school and at Ohio State, Eichelberger managed to become a cadet lieutenant and graduated 68th in his class of 103.

2.2. Early Military Career

Eichelberger's initial assignments in the U.S. Army began shortly after his graduation from West Point. He was commissioned as a second lieutenant in the 25th Infantry on June 11, 1909. A month later, on July 22, he transferred to the 10th Infantry at Fort Benjamin Harrison, Indiana.

In March 1911, the 10th Infantry was deployed to San Antonio, Texas, where it became part of the Maneuver Division, a unit formed for offensive operations during the Border War with Mexico. In September of the same year, his unit was sent to the Panama Canal Zone. It was in Panama that Eichelberger met Emmaline (Em) Gudger, the daughter of Hezekiah A. Gudger, who served as the Chief Justice of the Panama Canal Zone Supreme Court. After a brief courtship, they were married on April 3, 1913.

Upon returning to the United States in March 1915, Eichelberger was assigned to the 22nd Infantry at Fort Porter, New York. This unit was also dispatched to the Mexican border, based at Douglas, Arizona, where Eichelberger was promoted to first lieutenant on July 1, 1916. In September, he transitioned to an academic role, becoming Professor of Military Science and Tactics at Kemper Military School in Boonville, Missouri.

3. World War I and Siberian Intervention

Eichelberger's service during World War I and his subsequent deployment to Siberia marked a critical period in his early military career, exposing him to complex international and military challenges.

3.1. World War I Service

Following the American entry into World War I in April 1917, Eichelberger received a promotion to captain on May 15. In June, he was posted to the 20th Infantry at Fort Douglas, Utah, where he commanded a battalion. In September, he transferred to the newly formed 43rd Infantry at Camp Pike, Arkansas. He served as Senior Infantry Instructor at the 3rd Officers' Training Camp at Camp Pike until February 1918, when he was assigned to the War Department General Staff in Washington, D.C. There, he became an assistant to Brigadier General William S. Graves and was promoted to major on June 3, 1918.

3.2. Siberian Expedition

In July 1918, General Graves was appointed commander of the 8th Division, then based in Palo Alto, California, with orders to deploy to France within 30 days. Graves brought Eichelberger along as his Assistant Chief of Staff, G-3 (Operations). However, while en route to California, Eichelberger learned that the 8th Division's destination had been changed to Siberia. President Woodrow Wilson had agreed to support the Allied intervention in the Russian Civil War, and Graves was to command the American Expeditionary Force Siberia (AEFS). The AEFS departed San Francisco on August 15, with Eichelberger serving as its Assistant Chief of Staff, G-2 (Intelligence).

Graves' mission was more political than military, with instructions to "maintain strict neutrality." Eichelberger found himself in a complex political, diplomatic, and military environment. He was appointed to the ten-nation Inter-Allied Military Council, responsible for Allied strategy. Eichelberger quickly became convinced that America's objectives in Siberia differed from those of its French and British allies, and the lack of clear directives, coupled with disagreements between the State Department and the War Department, further complicated matters. American policy called for protecting the Trans-Siberian Railway, which was under the control of Admiral Alexander Kolchak's White Army forces, whom Eichelberger critically described as "murderers" and "cutthroats."

For his exceptional bravery during the Siberian Expedition, Eichelberger was awarded the Distinguished Service Cross. His citation highlighted several acts of heroism: "On July 2, 1919, after the capture, by American troops of Novitskaya, an American platoon detailed to clear hostile patrols from a commanding ridge was halted by enemy enfilading fire, seriously wounding the members of the patrol. Colonel Eichelberger, without regard to his own safety and armed with a rifle, voluntarily covered the withdrawal of the platoon. On June 28, at the imminent danger of his own life, he entered the partisan lines and effected the release of one American officer and three enlisted men in exchange for a Russian prisoner. On July 3, an American column being fired upon when debouching from a mountain pass, Colonel Eichelberger voluntarily assisted in establishing the firing line, prevented confusion, and, by his total disregard for his own safety, raised the morale of the American forces to a high pitch."

For his services in Siberia, Eichelberger also received the Army Distinguished Service Medal and was promoted to lieutenant colonel on March 28, 1919. Although General Graves prevented him from receiving the British Distinguished Service Order and the French Legion of Honor, which had been awarded to other members of the Inter-Allied Military Council, Eichelberger did receive several Japanese honors: the Imperial Order of Meiji, the Order of the Sacred Treasure, and the Order of the Rising Sun. His time in Siberia allowed Eichelberger to observe the Japanese Army firsthand, and he was impressed by their training and discipline, concluding that they would be a formidable opponent for American troops if properly led. The AEFS was eventually withdrawn in April 1920.

4. Interwar Period Activities

Between the two World Wars, Eichelberger continued his military career, focusing on intelligence, staff work, and professional development, which included significant interactions with future military leaders.

4.1. Service in the Philippines and United States

Instead of immediately returning to the United States after his service in Siberia, Eichelberger became Assistant Chief of Staff, G-2 (Intelligence), of the Philippine Department on May 4, 1920. Like many officers after World War I, his rank was temporarily reduced to his permanent rank of captain on June 30, 1920, but he was immediately promoted back to major the following day. His wife, Em, joined him in Vladivostok in March 1920, and they traveled together to Japan before moving on to the Philippines.

In March 1921, Eichelberger was appointed head of the Intelligence Mission to China. During this assignment, he established intelligence offices in Peking and Tientsin and met with Sun Yat-sen, the President of the Republic of China. He finally returned to the United States in May 1921, where he was assigned to the Far Eastern Section of the G-2 (Intelligence) Division of the War Department General Staff.

A significant professional setback for Eichelberger during this period was his failure to be included on the General Staff Eligibility List (GSEL). Under the National Defense Act of 1920, only officers on this list were eligible for promotion to brigadier general. Concluding that his prospects for promotion within the infantry were limited, he transferred to the Adjutant General's Corps on July 14, 1925, at the urging of the Adjutant General, Major General Robert C. Davis. He continued to work with the War Department General Staff, but now within the Adjutant General's Office. In April 1925, he was posted to Fort Hayes, Ohio, as Assistant Adjutant General for the 5th Corps Area.

4.2. Staff College and Education

Major General Davis nominated Eichelberger for a place at the Command and General Staff College at Fort Leavenworth. Eichelberger joined 247 other officers there in July 1924. Due to alphabetical seating, he sat next to Major Dwight D. Eisenhower, who would later top the class. Other notable students in his class included Joseph Stilwell, Leonard Gerow, and Joseph T. McNarney. Eichelberger graduated as a Distinguished Graduate, placing within the top quarter of his class, and remained at the college as its Adjutant General. In 1929, he became a student at the Army War College. Following his graduation, he was posted back to the Adjutant General's Office in Washington, D.C.

4.3. Relationship with Douglas MacArthur

In 1931, Eichelberger was sent to West Point to serve as its adjutant. He was promoted to lieutenant colonel on August 1, 1934. In April 1935, he became Secretary of the War Department General Staff, working directly for the Chief of Staff of the United States Army, General Douglas MacArthur. This period marked a significant professional interaction with MacArthur, a figure who would later dominate much of Eichelberger's World War II service. Eichelberger transferred back to the infantry in July 1937, though he remained Secretary of the War Department General Staff until October 1938, holding the rank of colonel from August 1.

The new Chief of Staff, General Malin Craig, offered Eichelberger command of the 29th Infantry, a demonstration regiment based at Fort Benning, Georgia. Eichelberger declined this prestigious offer, citing his many years away from the infantry and potential resentment from other infantry officers. Instead, he accepted command of the 30th Infantry, a less prominent unit stationed at the Presidio of San Francisco. Even with this choice, some officers still expressed resentment that he attained regimental command at the age of 52. Before taking up this new command, he attended a brief course at the Infantry School at Fort Benning to reacquaint himself with infantry operations. As part of the 3rd Infantry Division, the 30th Infantry participated in a series of major training exercises over the subsequent two years.

5. World War II

Robert Eichelberger's command responsibilities during World War II were extensive, encompassing significant training reforms, challenging jungle warfare, and leadership of the newly formed Eighth Army in crucial Pacific campaigns.

5.1. Commands and Training in the United States

Eichelberger was promoted to brigadier general in October 1940. The following month, he received orders to become the deputy division commander of the 7th Infantry Division under Joseph Stilwell. However, these orders were changed at the last minute when Major General Edwin "Pa" Watson intervened with President Franklin Roosevelt to have Eichelberger appointed Superintendent of the United States Military Academy at West Point. Before assuming this role, Eichelberger met with George C. Marshall, Craig's successor as Chief of Staff, who cautioned him that the courses at the Command and General Staff College and Army War College had been drastically shortened to meet the needs of the expanding Army, and that West Point would face a similar fate unless Eichelberger could make its curriculum more relevant to the Army's immediate needs.

As superintendent, Eichelberger aimed "to bring West Point into the twentieth century." He reduced activities such as horseback riding and close order drill, replacing them with modern combat training. This new training involved cadets participating in military exercises alongside National Guard units. He also acquired Stewart Field as a training facility, which allowed cadets to qualify as pilots while still at West Point. Beyond military training, Eichelberger also addressed the poor performance of the West Point football team. Through Pa Watson, he successfully lobbied the Surgeon General of the United States Army to waive weight restrictions, enabling the recruitment of heavier players, and hired Earl Blaik to coach the team.

Over time, Marshall came to believe that Eichelberger's talents were being underutilized at West Point, but Pa Watson opposed his transfer. When Marshall informed Watson that Eichelberger's chances for promotion to major general were being negatively affected by his inability to command a division, Watson added Eichelberger's name to the top of a promotion list, which the President then signed. This led to Eichelberger's promotion to major general in July 1941.

After the United States declaration of war upon Japan in December 1941, Eichelberger applied for a transfer to an active command. He was given a choice of three new divisions and selected the 77th Infantry Division, which was activated at Fort Jackson, South Carolina, in March 1942. The other two divisions were assigned to Major Generals Omar Bradley and Henry Terrell, Jr.. All three generals and their staffs attended a training course at Fort Leavenworth. For his chief of staff, Eichelberger chose Clovis Byers, an officer who had also attended Ohio State and West Point and was a fellow member of the Phi Gamma Delta fraternity.

Eichelberger's command of the 77th Infantry Division was brief. On June 18, 1942, he became commander of I Corps, with Byers serving as his chief of staff. For his service with the 77th Infantry Division, he was awarded the Legion of Merit. I Corps comprised the 8th, 30th, and 77th Infantry Divisions. Eichelberger's initial task was to arrange a military demonstration for high-ranking dignitaries, including Winston Churchill, Marshall, Henry Stimson, Sir John Dill, and Sir Alan Brooke. Although the demonstration was deemed a success, the experienced eyes of Brooke and Lesley McNair noted flaws, leading to the relief of two division commanders within days. Eichelberger was then nominated to command American forces in Operation Torch and was ordered to conduct amphibious warfare training with the 3rd, 9th, and 30th Infantry Divisions in Chesapeake Bay in cooperation with Rear Admiral Kent Hewitt.

5.2. New Guinea Campaign

On August 9, 1942, Eichelberger's orders were abruptly changed. Douglas MacArthur, then Supreme Commander of the Southwest Pacific Area, had requested a corps headquarters be sent to his command. Major General Robert C. Richardson, Jr. had originally been designated for the assignment, but Marshall informed MacArthur that "Richardson's intense feelings regarding service under Australian command made his assignment appear unwise." Eichelberger's I Corps headquarters was prepared for overseas service, had experience in amphibious warfare, and Eichelberger himself had prior experience working with MacArthur, leading Marshall to select him instead. Eichelberger was not pleased with the assignment, particularly after learning about Richardson's reluctance, and noted that he "knew General MacArthur well enough to know that he was going to be difficult to get along with."

Eichelberger departed for Australia on August 20 with 22 members of his staff in a B-24 Liberator. I Corps assumed control of the two American divisions in Australia: Major General Forrest Harding's 32nd Infantry Division at Camp Cable near Brisbane, and Major General Horace Fuller's 41st Infantry Division at Rockhampton, Queensland. Eichelberger, who was promoted to lieutenant general on October 21, decided to establish his I Corps headquarters inside the Criterion Hotel in Rockhampton. His I Corps operated under the command of Lieutenant General Sir John Lavarack's Australian First Army. Eichelberger observed that many Australian commanders, having seen combat with the British in North Africa, "considered the Americans to be-at best-inexperienced theorists," though they were usually polite. He was concerned by the training level of the two American divisions, noting they were following the same syllabus used in the United States instead of training for jungle warfare. He warned MacArthur and his chief of staff, Major General Richard K. Sutherland, that the divisions could not be expected to meet veteran Japanese troops on equal terms. In September, he decided that the 32nd Infantry Division should proceed to New Guinea first, as Camp Cable was inferior to the 41st Infantry Division's camp at Rockhampton.

Eichelberger's concerns were validated when the overconfident 32nd Infantry Division suffered a severe setback in the Battle of Buna-Gona. Harding was confident he could capture Buna "without too much difficulty," but poor staff work, inaccurate intelligence, inadequate training, and fierce Japanese resistance thwarted American efforts. The Americans faced a network of well-sited and expertly prepared Japanese positions, accessible only through a swamp. The Americans' failure damaged their relationship with the Australians and threatened to derail MacArthur's entire campaign. Eichelberger and a small party from I Corps headquarters were hastily flown to Port Moresby in a pair of C-47 Dakotas on November 30. MacArthur ordered Eichelberger to assume control of the battle at Buna. According to Byers and Eichelberger, MacArthur told him "in a grim voice": "I'm putting you in command at Buna. Relieve Harding. I am sending you in, Bob, and I want you to remove all officers who won't fight. Relieve regimental and battalion commanders; if necessary, put sergeants in charge of battalions and corporals in charge of companies-anyone who will fight. Time is of the essence; the Japanese may land reinforcements any night." General MacArthur strode down the breezy veranda again. He said he had reports that American soldiers were throwing away their weapons and running from the enemy. Then he stopped short and spoke with emphasis. He wanted no misunderstandings about my assignment. "Bob," he said, "I want you to take Buna, or not come back alive." He paused a moment, and then, without looking at Byers, pointed a finger. "And that goes for your chief of staff, too."

The next day, Eichelberger's party flew to Dobodura, where he assumed command of U.S. troops in the Buna area. He relieved Harding, replacing him with the division's artillery commander, Brigadier General Albert W. Waldron. He also relieved other officers, including appointing a 26-year-old captain to command a battalion. Some officers of the 32nd Infantry Division privately denounced Eichelberger as ruthless and "Prussian." He set an example by moving among the troops on the front lines, sharing their hardships and danger. Despite the risk, he purposefully wore his three silver stars while at the front, even though he knew Japanese snipers targeted officers, because he wanted his troops to know their commander was present. After the snipers seriously wounded Waldron in the shoulder, Eichelberger appointed Byers to command the 32nd Infantry Division, but he too was wounded on December 16. This left Eichelberger as the only American general in the forward area, and he assumed personal command of the division. He was not the most senior general present though; he served under the command of Australian Lieutenant General Edmund Herring, whom he referred to in letters to his wife, Em, as "my grand colleague."

After the fall of Buna, Eichelberger was placed in command of the Allied force assembled to reduce the remaining Japanese positions around Sanananda, with Australian Major General Frank Berryman as his chief of staff. The battle continued until January 22, 1943. The victory at Buna came at a high cost: the 32nd Division suffered 707 dead and 1,680 wounded, with an additional 8,286 hospitalized due to tropical diseases, primarily malaria. Its men referred to their division cemetery as "Eichelberger Square." On January 24, Eichelberger flew back to Port Moresby, where he was warmly welcomed by Herring. The next day, he returned to Rockhampton. For the battle, Eichelberger received the Distinguished Service Cross along with ten other generals, all of whom received the same citation. Some, like Herring, had served at the front; others, like Sutherland, had not. Eichelberger was also created an honorary Knight Commander of the Order of the British Empire. Byers recommended Eichelberger for the Medal of Honor but the nomination was disapproved by MacArthur. Another officer on Eichelberger's staff, Colonel Gordon B. Rogers then submitted the recommendation directly to the War Department. MacArthur informed the War Department that "Among many outside the immediate staff of this officer, there was criticism of his conduct of operations which while not detracting from his personal gallantry led to grave considerations at one time of his relief from command."

5.3. Major Operations in the Pacific Theater

In February 1943, Lieutenant General Walter Krueger's Sixth United States Army headquarters arrived in Australia. With Sixth Army handling most of the planning and limited scope for corps-sized operations, Eichelberger's role shifted to training. He was responsible for preparing the 24th Infantry Division, which had arrived from Hawaii, and the 32nd and 41st Infantry Divisions, which had returned from Papua, for future missions. In May 1943, the War Department inquired if Eichelberger could be released to command the First United States Army, but MacArthur refused. Later, a request for him to command the Ninth United States Army was also denied, with that position ultimately going to Eichelberger's West Point classmate, William H. Simpson. Instead, in September 1943, Eichelberger was given responsibility for Eleanor Roosevelt's visit to Australia, during which she visited Sydney, Melbourne, and Rockhampton, and had dinner with the Governor General of Australia, Lord Gowrie, and the Prime Minister of Australia, John Curtin, in Canberra.

In January 1944, Eichelberger was informed that he would lead the next operation, a landing at Hansa Bay with the 24th and 41st Infantry Divisions. However, in March, this plan was canceled in favor of Operation Reckless, a landing by the same force at Hollandia. The operation meant leapfrogging the Japanese defenses at Hansa Bay, but was risky because it was outside the range of land-based air cover. Cover was instead provided by aircraft carriers of the United States Pacific Fleet, but this meant that the operation had to adhere to a strict timetable. Hoping to avoid a repeat of Buna, Eichelberger meticulously planned the operation, and implemented a thorough training program that emphasized physical fitness, individual initiative, small unit tactics, and amphibious warfare. The operation went well, mainly because surprise was achieved and few Japanese were present in the area. However, poor topographical intelligence led to an inability to clear some beaches due to their being backed by swamps. Supplies piled up on the beaches, with fuel and ammunition being stored together in some instances. On April 23, a single Japanese plane ignited a fuel dump, which caused a fire that resulted in 124 casualties and the loss of 60 percent of the ammunition stockpile. An appalled Krueger felt that Eichelberger had been let down by his staff, and offered to transfer Byers to an assistant division commander's post, but Eichelberger turned down the offer.

In June 1944, Eichelberger was summoned to Sixth Army headquarters by Krueger. The Battle of Biak, where the 41st Infantry Division had landed in May, was going badly, and the airfields that MacArthur had promised would be available to support the Battle of Saipan were not in American hands. Eichelberger found that the Japanese, who were present in larger numbers than originally reported, were ensconced in caves overlooking the airfield sites. While the Americans were better trained and equipped than at Buna, so too were the Japanese, who employed their new tactics of avoiding costly counterattacks and exacting the maximum toll for ground gained. After seeing the situation for himself, Eichelberger concluded that Fuller's 41st Infantry Division had not done too badly. Nonetheless, as at Buna, Eichelberger relieved a number of officers that he felt were not performing as the battle ground on. His orders were to supersede Fuller as task force commander rather than relieve him as division commander, but Fuller requested his own relief, and Krueger obliged him. On Eichelberger's recommendation, Fuller was replaced by Brigadier General Jens A. Doe. Krueger was unimpressed with Eichelberger's performance on Biak, concluding that Eichelberger's tactics were unimaginative, and no better than Fuller's, and may have delayed rather than expedited the capture of the island. On the other hand, MacArthur thought sufficiently highly of Eichelberger's performance to award him the Silver Star.

5.4. Role as Commander of the Eighth Army

While still on Biak, Eichelberger learned that MacArthur had selected him to command the newly formed Eighth United States Army. The Eighth Army arrived at Hollandia in August 1944. Eichelberger took two officers with him from I Corps: Byers and Colonel Frank S. Bowen, his G-3. The Eighth Army assumed control of operations on Leyte Island from Sixth Army on December 26, the day after MacArthur and Krueger announced that organized resistance there had ended. Among the troops on Leyte was Eichelberger's old command, the 77th Infantry Division. In two months, Sixth Army had killed over 55,000 Japanese soldiers on Leyte, and estimated that only 5,000 remained alive on the island. By May 8, 1945, the Eighth Army had killed over 24,000 more.

In January, the Eighth Army entered combat on Luzon, landing Major General Charles P. Hall's XI Corps on January 29 near San Antonio and Major General Joseph M. Swing's 11th Airborne Division at Nasugbu, Batangas two days later. Combining with Sixth Army, the Eighth Army enveloped Manila in a great pincer movement. Eichelberger assumed personal command of the operation, which involved an advance on Manila by the lightly equipped 11th Airborne Division. The audacious advance made rapid progress until it was halted by well-prepared positions on the outskirts of Manila. MacArthur awarded Eichelberger another Silver Star.

The Eighth Army's final major operation of the war was that of clearing out the southern Philippines, including the major island of Mindanao, an effort that occupied the soldiers of the Eighth Army for the rest of the war. In six weeks, the Eighth Army conducted 14 major and 24 minor amphibious operations, clearing Mindoro, Marinduque, Panay, Negros, Cebu, and Bohol. In August 1945, Eichelberger's Eighth Army became part of the Occupation of Japan. In the one instance when the Japanese formed a self-help vigilante guard to protect women from rape by off-duty GIs, the Eighth Army ordered armoured vehicles in battle array into the streets and arrested the leaders, and the leaders received long prison terms. The only source for this account is Eichelberger's diary, which does not mention any sex crimes but does mention the beatings of several GIs.

For his distinguished service, Eichelberger was awarded an oak leaf cluster to his Distinguished Service Medal for his services as commander of I Corps, a second for his command of Eighth Army in the Philippines, and a third for the occupation of Japan. He also received the Navy Distinguished Service Medal, two oak leaf clusters to his Silver Star Medal, the Bronze Star Medal, and the Air Medal. He also received a number of foreign awards, including Grand Officer of the Order of Orange Nassau with swords from the Netherlands, Grand Officer of the Legion of Honour from France, Grand Officer of the Order of the Crown and the Croix de Guerre with palm from Belgium, the Order of Abdon Calderón from Ecuador, the Distinguished Service Star, Liberation Medal, and Legion of Honor from the Philippines, and Grand Officer of the Military Order of Italy.

6. Occupation of Japan and Post-War Activities

Eichelberger's command of the Eighth Army during the Allied occupation of Japan was a significant phase of his career, where he navigated complex political and security issues, and his post-war engagements continued to shape his legacy.

6.1. Occupation Duties in Japan

Robert Eichelberger arrived in Japan on August 30, 1945, landing at Atsugi Airfield. As the commander of the Eighth United States Army, he was the second-highest ranking official in the Allied occupation forces, serving directly under Supreme Commander Douglas MacArthur. In this capacity, he was the senior officer responsible for formally greeting MacArthur upon his arrival in Japan. Eichelberger's Eighth Army commenced a three-year period of duties as part of the Allied occupation. Due to his generally warm personality, Eichelberger earned a significant degree of trust from the Japanese government. This trust led to the establishment of an informal but effective communication channel, often referred to as the "Eichelberger route," which facilitated negotiations between the Japanese government and MacArthur when direct discussions proved difficult.

6.2. Activities Related to Japanese Rearmament and Security Policy

Before his departure from Japan, Eichelberger became a vocal advocate for the rearmament of Japan, a stance that put him at odds with the Civil Affairs Bureau (Civilian Information and Education Section or CI&E) and the Far Eastern Commission. Although full rearmament did not occur during his tenure, he played a crucial role in establishing the Maritime Safety Agency, which significantly contributed to Japan's post-war security framework.

A notable event reflecting his influence on Japan's security policy was the "Ashida Memo." This document, sent by Japanese Foreign Minister Hitoshi Ashida of the Katayama Cabinet to Eichelberger via Kuman Suzuki, the Director of the Yokohama Liaison Office for End of War, expressed Japan's willingness to entrust its national security to the United States. This exchange is widely considered to be a foundational step and a prototype for the eventual Japan-US Security Treaty.

6.3. Relationship with Douglas MacArthur and Personal Evaluation

Eichelberger's relationship with General Douglas MacArthur was complex. While he maintained a public facade of professional cooperation and did not openly challenge his superior, his private diaries and papers reveal scathing criticisms of MacArthur. These personal writings, later published, offer a contrasting perspective to the public narrative of their collaboration. Eichelberger also harbored lasting resentment towards other figures, such as Krueger and Sutherland, for perceived slights, refusing to speak with Sutherland even when he attempted reconciliation.

Eventually, Eichelberger decided to write a tell-all book intended to "destroy the MacArthur myth forever." To facilitate this, he entrusted his personal papers to Duke University. His wartime letters were later published in 1972 by historian Jay Luuvas as Dear Miss Em: General Eichelberger's War in the Pacific 1942-1945. Despite these strained relationships, Eichelberger maintained a warm post-war friendship with Australian Lieutenant General Edmund Herring, his "grand colleague" from the Buna campaign. Herring and his wife, Mary, visited the Eichelbergers in Asheville in 1953, and they regularly exchanged letters.

7. Retirement and Death

After a distinguished career spanning nearly 40 years, Robert Eichelberger retired with the rank of lieutenant general on December 31, 1948. In 1950, he and his wife, Em, moved to Asheville, North Carolina, where they resided for the remainder of his life. Eichelberger faced several health challenges in retirement, including hypertension and diabetes, and underwent a gall bladder removal.

His experiences during the campaigns in the Southwest Pacific were serialized in a series of articles for the Saturday Evening Post, which were ghostwritten by Milton MacKaye. These articles were subsequently expanded into a book titled Our Jungle Road to Tokyo, which one reviewer described as "a straightforward and modest account of the campaigns of the Army ground forces from the Buna operation to the Philippines and victory." The book achieved reasonable sales, and notable figures such as Harry Truman and Omar Bradley requested autographed copies. In 1951, Eichelberger traveled to Hollywood, where he served as a technical consultant for the films Francis Goes to West Point (1952) and The Day the Band Played (1952), although he was not entirely satisfied with the final results. He also contributed articles on the Far East to Newsweek until 1954, and later engaged in the lecture circuit, giving speeches about his experiences until 1955. In his later years, he remained politically active, campaigning for Richard Nixon in 1960.

In recognition of his extensive service, the United States Congress promoted Eichelberger, along with several other officers who had commanded armies or similar higher formations during World War II, to the rank of general in 1954. Despite this honor, he remained distressed that Generals Harding and Fuller were still hurt and angry with him over being relieved of their commands, an outcome he felt was primarily MacArthur's fault. Conversely, Eichelberger never forgave Krueger or Sutherland for real or imagined slights, even refusing to speak with Sutherland when he attempted to engage him. Eichelberger ultimately decided to write a comprehensive book that "would destroy the MacArthur myth forever," and for this purpose, he donated his papers to Duke University. His letters were later published in 1972 by historian Jay Luuvas as Dear Miss Em: General Eichelberger's War in the Pacific 1942-1945.

Eichelberger underwent exploratory prostate surgery in Asheville on September 25, 1961. Complications arose, and he died from pneumonia the following day. He was buried with full military honors in Arlington National Cemetery.

8. Military Career Summary and Decorations

Robert Lawrence Eichelberger's military career spanned nearly four decades, marked by steady promotions and numerous decorations from both the United States and foreign nations, reflecting his extensive service across multiple conflicts and commands.

8.1. Major Decorations and Awards

Eichelberger received a wide array of military decorations and awards for his distinguished service:

| Award | Notes |

|---|---|

Distinguished Service Cross | With oak leaf cluster (2 awards) |

Army Distinguished Service Medal | With three oak leaf clusters (4 awards) |

Navy Distinguished Service Medal | |

Silver Star | With two oak leaf clusters (3 awards) |

Legion of Merit | |

Bronze Star Medal | |

Air Medal | |

Mexican Border Service Medal | |

Victory Medal | |

American Defense Service Medal | |

Asiatic-Pacific Campaign Medal | |

World War II Victory Medal | |

Army of Occupation Medal |

He also received numerous foreign awards:

| Award | Nation |

|---|---|

Knight Commander of the Order of the British Empire | Australia |

Companion of the Distinguished Service Order | United Kingdom |

Grand Officer of the Order of Orange Nassau with swords | Netherlands |

Grand Officer of the Legion of Honor | France |

Order of the Rising Sun | Japan |

Order of the Sacred Treasure | Japan |

Grand Officer Order of the Crown | Belgium |

Grand Officer Croix de Guerre with palm | Belgium |

First Class Order of Abdon Calderón | Ecuador |

Distinguished Service Star | Philippines |

Liberation Medal | Philippines |

Legion of Honor | Philippines |

Grand Officer of the Military Order of Italy | Italy |

8.2. Dates of Rank

Eichelberger's progression through the ranks of the United States Army is detailed below:

| Insignia | Rank | Component | Date |

|---|---|---|---|

| No pin insignia in 1909 | Second Lieutenant | Regular Army | 11 June 1909 |

| First Lieutenant | Regular Army | 1 July 1916 | |

| Captain | Regular Army | 15 May 1917 | |

| Major | (temporary) | 3 June 1918 | |

| Lieutenant Colonel | (temporary) | 28 March 1919 | |

| Reverted to permanent rank of Captain | Regular Army | 30 June 1920 | |

| Major | Regular Army | 1 July 1920 | |

| Lieutenant Colonel | Regular Army | 1 August 1934 | |

| Colonel | Regular Army | 1 August 1938 |

| Brigadier General | Army of the United States | 1 October 1940 | |

| Major General | Army of the United States | 10 July 1941 |

| Lieutenant General | Army of the United States | 21 October 1942 |

| Brigadier General | Regular Army | 1 September 1943 | |

| Major General | Regular Army | 4 October 1944 |

| Lieutenant General | Regular Army, Retired | 31 December 1948 |

| General | Regular Army, Retired | 19 July 1954 |

9. Impact and Assessment

Robert Eichelberger's career had a profound impact on military history and international relations, particularly through his leadership in the Pacific Theater and his role in the post-war occupation of Japan. His leadership style, personal interactions, and policy recommendations contributed significantly to the shaping of post-war Japan.

9.1. Unique Anecdotes with Japan

During the occupation of Japan, Eichelberger, as the second-highest ranking official, was involved in several unique incidents that illustrate the dynamics of the post-war relationship. The National Railways designated several special railway carriages for General Eichelberger's exclusive use, including Imperial Train Car No. 10, Imperial Train Car No. 11, マイネ38 1Maine 38 1Japanese, スイロネフ38 1Suironefu 38 1Japanese, マイロネ38 1Mairone 38 1Japanese, and スハニ33 13Suhani 33 13Japanese.

In 1947, a notable incident occurred at Usui Pass during Emperor Showa's regional tour. The Emperor's imperial train and Lieutenant General Eichelberger's Allied Forces' special train were scheduled to pass each other. Under orders from the Railway Transportation Office (RTO), the Emperor's train was directed to pull aside and wait for five minutes to allow Eichelberger's train to pass. This event highlighted the shift in authority during the occupation period.

During his stay in Karuizawa, Eichelberger visited the Western-style painter Rikuo Arai and commissioned a portrait, reflecting a unique cultural interaction during his time in Japan.

9.2. Historical Assessment and Criticism

Eichelberger is often remembered for his "warm personality" and the trust he garnered from the Japanese government, which facilitated the "Eichelberger route" for negotiations with MacArthur. His advocacy for Japanese rearmament before his departure, despite opposition from the Civil Affairs Bureau and the Far Eastern Commission, underscores his forward-looking perspective on regional stability. The "Ashida Memo," which expressed Japan's desire to entrust its security to the United States, is considered a significant precursor to the Japan-US Security Treaty, demonstrating Eichelberger's influence on the foundational aspects of post-war Japanese security policy.

However, Eichelberger's leadership was not without controversy. His direct and demanding approach during combat operations, particularly at Buna and Biak, led to the relief of several officers and earned him the private moniker of "ruthless" and "Prussian" from some of his subordinates. While his personal gallantry was recognized, MacArthur's disapproval of his Medal of Honor nomination and the Supreme Commander's note about "criticism of his conduct of operations" indicate internal tensions regarding his command style.

Furthermore, during the occupation of Japan, an incident occurred where the Eighth Army suppressed a self-help vigilante guard formed by Japanese citizens to protect women from rape by off-duty GIs. The Eighth Army responded by deploying armored vehicles and arresting the vigilante leaders, who subsequently received long prison terms. It is important to note that Eichelberger's personal diary, the sole source for this account, mentions the beatings of several GIs but does not describe any sex crimes. His private diaries also contained scathing criticisms of MacArthur, revealing a complex and often strained relationship with his superior, a dynamic that he sought to expose in his later years through his writings. Overall, Eichelberger's career reflects a blend of effective military leadership, significant diplomatic engagement during the occupation, and a complex personal legacy marked by both admiration and criticism.

10. External Links

- [http://www.library.duke.edu/rubenstein/findingaids/eichel/ Robert L. Eichelberger Papers, 1728-1998 (bulk 1942-1949)]

- [http://www.library.duke.edu/digitalcollections/esr/robert-l-eichelberger/ Images from the Robert L. Eichelberger Collection - Duke University Libraries Digital Collections]

- [https://generals.dk/general/Eichelberger/Robert_Lawrence/USA.html Generals of World War II]

- [https://www.unithistories.com/officers/US_Army_officers_E01.html#Eichelberger_RL United States Army Officers 1939-1945]

- [https://www.sankei.com/article/20150719-H27A675V6ZKCPEBWVYBZE7DEZA/ Sankei News article on Ashida Memo]

- [https://www.tobunken.go.jp/materials/bukko/9405.html 'Nihon Bijutsu Nenkan' (Japan Art Annual) entry for Rikuo Arai]

- [https://dl.ndl.go.jp/info:ndljp/pid/1352269/63 Details on special railway carriages for General Eichelberger from 'Allied Forces Passenger Train and Special Car Handling Procedures']

- [http://www.arlingtoncemetery.net/rleichelberger.htm Robert L. Eichelberger at Arlington National Cemetery]