1. Overview

Pope Leo IX, born Bruno von Egisheim-DagsburgGerman, served as the head of the Catholic Church and ruler of the Papal States from February 12, 1049, until his death on April 19, 1054. Considered one of the most historically significant popes of the Middle Ages, his pontificate was marked by extensive church reform efforts aimed at combating simony and enforcing clerical celibacy. He also played a pivotal, though controversial, role in the events that precipitated the East-West Schism of 1054, a critical turning point in the formal separation of the Catholic and Eastern Orthodox Churches. His reign also saw significant conflict with the Normans in Southern Italy, culminating in his military defeat and brief captivity. Leo IX is revered as a saint by the Catholic Church, with his feast day celebrated on April 19.

2. Early Life

Bruno von Egisheim-Dagsburg's early life was shaped by his noble lineage and a comprehensive education, which prepared him for a distinguished ecclesiastical career before his elevation to the papacy.

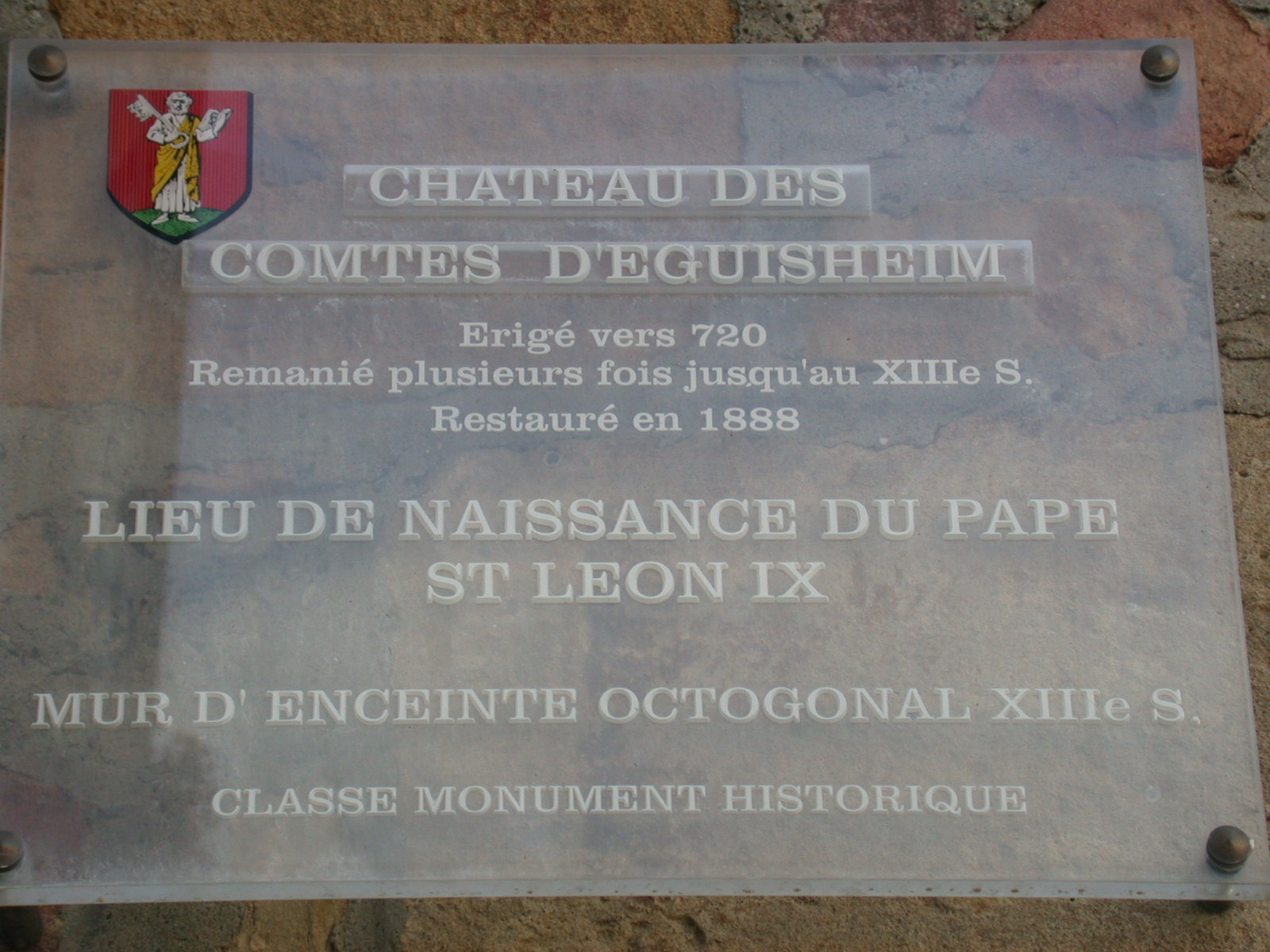

2.1. Birth and Family Background

Bruno was born on June 21, 1002, in Eguisheim, Upper Alsace (present-day Alsace, France). He hailed from the aristocratic Egisheim family, a branch of the Etichonids, known for their piety and loyalty to Christian teachings. His father was Hugh IV of Nordgau, a Frankish nobleman, and his mother was Heilwig of Dabo. Notably, his father was a first cousin of Conrad II, the Holy Roman Emperor, establishing strong familial ties to the imperial court.

2.2. Education and Early Ecclesiastical Career

At the tender age of five, Bruno was entrusted to the care of Berthold of Toul, Bishop of Toul, who operated a school for the sons of the nobility. Here, Bruno received a deep education in the Catholic faith, demonstrating remarkable intelligence and humility. In 1017, he became a canon at St. Stephen's in Toul. By 1024, following his cousin Conrad's succession to the imperial throne, Bruno's relatives sent him to the new king's court to serve in his chapel. He was ordained a deacon in 1026.

2.3. Bishop of Toul

In 1026, Bruno was appointed and subsequently consecrated as the Bishop of Toul in 1027. He administered the Diocese of Toul for over two decades, a period marked by considerable stress and challenges, including famine and frequent warfare due to Toul's frontier location. As bishop, Bruno became widely known as an earnest and reforming ecclesiastic. He zealously promoted the rule of the order of Cluny, frequently visiting monasteries and convening meetings within his diocese to spread its principles. He was committed to reforming the spiritual and moral life of his episcopate, enforcing discipline among the clergy, combating simony, and encouraging a life of purity among the faithful.

Bruno also rendered significant political services to both Emperor Conrad II and his successor, Henry III. He was adept at fostering peace, notably establishing a lasting peace between France and the Holy Roman Empire when sent by Conrad to Robert the Pious. Conversely, he was also capable of wielding the sword in self-defense, successfully defending his episcopal city against Count Odo II of Blois, a rebel against Conrad, and through his efforts, helped add Burgundy to the empire. During his tenure as bishop, Bruno experienced personal sorrow with the deaths of his parents and two brothers, finding solace in music, in which he was highly proficient.

3. Papal Election and Accession

The selection of Bruno as Pope followed a unique process, highlighting his commitment to canonical tradition and setting the stage for his reformist pontificate.

3.1. Election Process

Following the death of Pope Damasus II in 1048, a vacancy arose in the papacy. In December of that year, an assembly convened at Worms to select a successor. Both the Holy Roman Emperor Henry III and the Roman delegates present concurred on the nomination of Bruno, then Bishop of Toul, as the next Pope.

3.2. Acceptance and Coronation

Despite being nominated by the emperor and Roman delegates, Bruno expressed a strong preference for a canonical election. He stipulated that his acceptance of the papal office was conditional upon his first proceeding to Rome and being freely elected by the clergy and people of Rome.

Shortly after Christmas, Bruno embarked on his journey to Rome. He traveled in pilgrim garb, a gesture symbolizing his humility and submission to divine will. Along the way, he met with Hugh of Cluny, the influential abbot of Cluny, at Besançon. It was here that he was joined by the young monk Hildebrand, who would later become Pope Gregory VII and a key figure in the Gregorian Reforms. Upon his arrival in Rome in February 1049, Bruno was received with immense cordiality and enthusiasm by the populace. In response to the clear desire of the Roman clergy and citizens, he formally accepted the papacy and was consecrated, assuming the name Leo IX. His accession on February 12, 1049, was surrounded by a group of young, dynamic reformers, including Hugh of Remiremont, Frederick of Lorraine (who would later become Pope Stephen IX), and Humbert of Silva Candida, all of whom would become instrumental in his papal agenda.

4. Papal Reign and Reform Activities

Pope Leo IX's pontificate was characterized by an unwavering dedication to comprehensive church reform, which he pursued through various means, including extensive travels and numerous synods.

4.1. Goals and Principles of Reform

Leo IX was a staunch advocate for restoring traditional morality and discipline within the Catholic Church. His primary reform goals were to combat the widespread practices of simony (the buying or selling of ecclesiastical privileges, such as pardons, offices, or sacred things) and to enforce clerical celibacy, which had become lax. Deeply influenced by the ideals of the Cluniac Reforms, he sought to purify the Church from corruption and strengthen the authority of the papacy against secular interference. To achieve this, he actively recruited talented reformers, including figures from the Cluny movement and the future Pope Gregory VII (Hildebrand), into the Papal Curia, thereby strengthening the Church's central administration and connecting numerous monasteries directly to Rome.

4.2. Synods and Councils

A hallmark of Leo IX's pontificate was his extensive travel throughout Europe, where he convened numerous synods and councils to implement his reform agenda. It is estimated that he spent less than half of his five-year reign in Rome, instead dedicating himself to these itinerant efforts.

One of his first major public acts as Pope was to hold the Easter Synod of 1049 in Rome. At this synod, the requirement for clerical celibacy, extending down to the rank of subdeacon, was unequivocally reaffirmed. Leo IX also successfully articulated his strong convictions against all forms of simony. Following this, he embarked on a grand tour through Italy, Germany, and France. After presiding over a synod in Pavia, he joined Emperor Henry III in Saxony and accompanied him to Cologne and Aachen.

He also summoned a meeting of the higher clergy in Reims, France, where several important reforming decrees were passed. Despite initial resistance from King Henry I, Leo IX entered French territory and, during the dedication ceremony of the Church of Saint Remi, compelled every attending bishop to swear that they had not received or conferred office through simony. Five bishops, including the Archbishop of Reims, were unable to take the oath, and while those who confessed were pardoned, this act significantly curbed simony and public offenses.

In Mainz, Germany, he held another significant council, attended by clergy from Italy, France, and Germany, as well as ambassadors from the Byzantine Empire. Here, too, simony and clerical marriage were the principal matters addressed.

Upon his return to Rome, Leo held a second Easter Synod on April 29, 1050. This council largely focused on the theological controversy surrounding Berengar of Tours and his teachings on the Eucharist. In the same year, he presided over provincial synods in Salerno, Siponto, and Vercelli. He revisited his native Germany in September, returning to Rome in time for a third Easter Synod, which debated the controversial issue of the reordination of those who had been ordained by simonists. In 1052, he met Emperor Henry III in Pressburg (modern-day Bratislava) in a vain attempt to secure the submission of the Hungarians. His presence was celebrated with ecclesiastical solemnities in Regensburg, Bamberg, and Worms.

4.3. Theological and Doctrinal Matters

Beyond his administrative and disciplinary reforms, Leo IX also engaged with significant theological debates of his time. A notable instance was the controversy concerning Berengar of Tours, who challenged the doctrine of the Real Presence of Christ in the Eucharist. Leo IX's synods, particularly the Easter Synod of 1050, condemned Berengar's views, asserting the orthodox teaching on the Eucharist. The question of reordination for clergy ordained by simonists was also a complex theological and canonical issue addressed during his papacy, reflecting the broader reform efforts to purify the Church's hierarchy.

5. Major Events and Conflicts

Pope Leo IX's pontificate was significantly shaped by two major external challenges: the escalating tensions with the Eastern Church, which culminated in the East-West Schism, and a military conflict with the Normans in Southern Italy.

5.1. Relations with Constantinople and the East-West Schism

The growing estrangement between the Eastern and Western Churches reached a critical point during Leo IX's papacy. Patriarch Michael I Cerularius of Constantinople, along with Leo of Ohrid, Archbishop of Bulgaria, openly criticized Latin Church practices, specifically the use of unleavened bread in the Eucharist and certain fasting days.

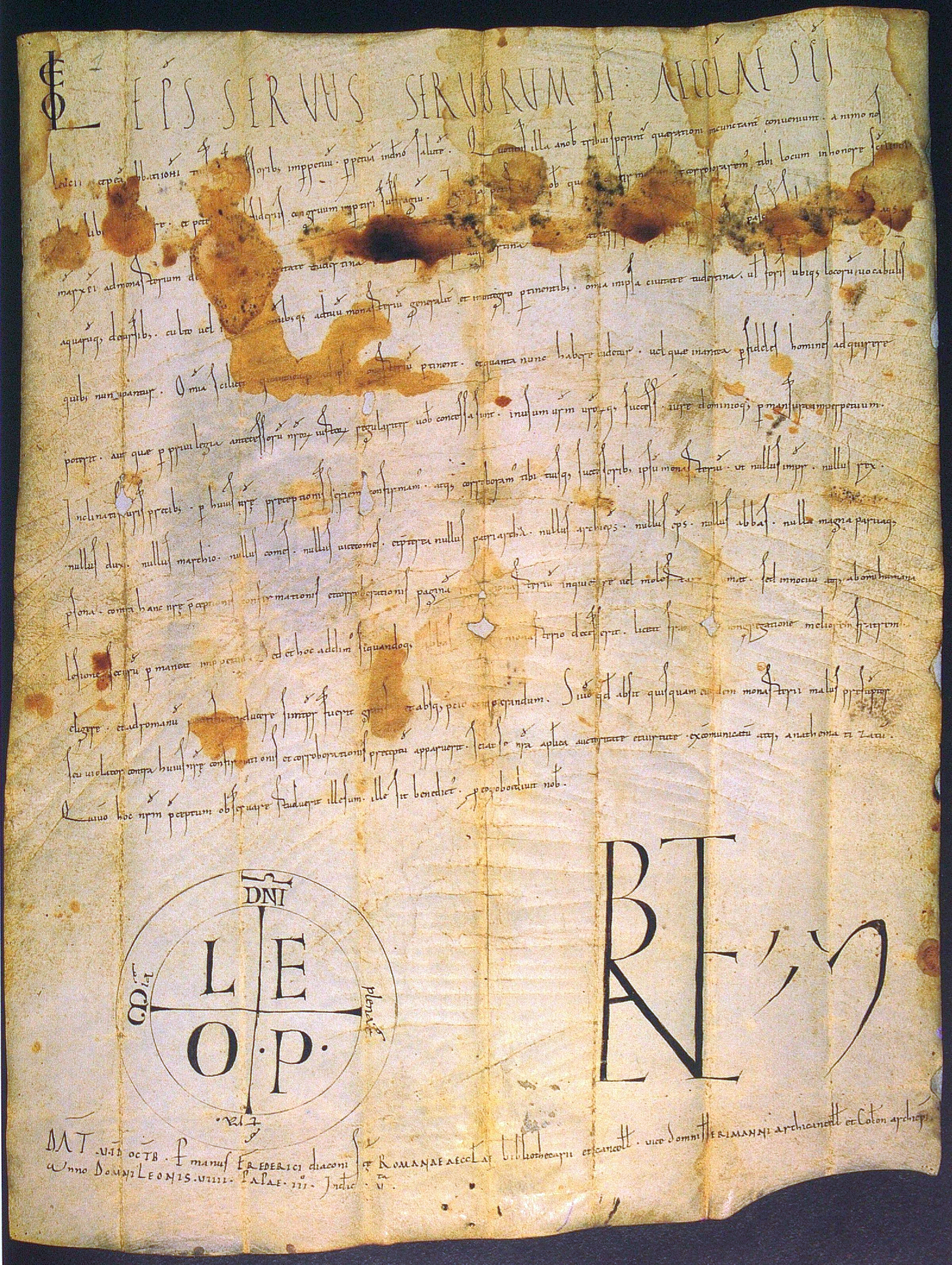

In response, Pope Leo IX sent a letter to Michael I in 1054, notably citing a substantial portion of the Donation of Constantine. This document, later proven to be a forgery, was believed by Leo IX to be genuine, and he used it to assert the primacy of the Roman See, claiming that only the apostolic successor to Peter possessed such authority and was the rightful head of the entire Church. This assertive stance, based on a fabricated document, further exacerbated tensions.

To negotiate with Patriarch Michael Cerularius, Leo IX dispatched a legatine mission to Constantinople, led by the uncompromising Cardinal Humbert of Silva Candida. Humbert's diplomatic approach was notably confrontational. He rejected any detailed debate on the specific points of contention raised by the Byzantines, instead focusing on asserting the supreme authority of the Apostolic See, which, according to him, "cannot be judged by anyone." The Eastern Church, however, maintained that all Latin masses were invalid. On July 16, 1054, in a highly provocative act, Cardinal Humbert placed a bull of excommunication against the Patriarch on the altar of the Hagia Sophia during a solemn liturgy. This act, though legally invalid due to Pope Leo IX's death on April 19, 1054, was met with a counter-excommunication by Patriarch Michael against Humbert and his associates. This exchange is popularly considered the formal and definitive split between the Eastern and Western Churches, marking the East-West Schism.

Following the excommunication, Michael Cerularius ordered the closure of Latin churches in Constantinople and removed the Pope's name from the diptychs, the liturgical lists of names to be commemorated. While Peter III of Antioch rejected most of Michael's accusations against Rome and urged compromise, his efforts were ultimately unsuccessful in preventing the schism. The Vietnamese source indicates that Emperor Constantine IX and Emperor Henry III, along with Pope Leo IX, had initially sought an alliance against the Normans and Muslims, and that Cerularius resented the Pope's influence in Southern Italy. The source also details Cerularius's specific criticisms of Latin rites, such as using unleavened bread ("dead bread"), eating meat without cutting the throat, Saturday fasting, and priests not having beards, which he viewed as deviations from true faith.

5.2. Conflict with the Normans

In Southern Italy, the Byzantine Empire faced constant threats from the expanding Normans. In desperation, the Byzantines appealed to Pope Leo IX, their spiritual leader, to "liberate Italy" and force the Normans, who were "pressing Apulia under their yoke," to withdraw.

After a fourth Easter Synod in 1053, Pope Leo IX personally led an army composed of Italians and Swabian mercenaries against the Norman forces in the south. The Normans, being devout Christians, were initially reluctant to engage in battle against their spiritual leader and attempted to sue for peace. However, the Swabian mercenaries in Leo's army reportedly mocked the Normans, making battle inevitable. On June 15, 1053, Leo IX's forces suffered a decisive defeat at the Battle of Civitate.

Despite his military loss, when Leo IX emerged from the city to meet the victorious Normans, he was received with unexpected deference, pleas for forgiveness, and oaths of fidelity and homage. Nevertheless, from June 1053 to March 1054, the Pope was held in honorable captivity at Benevento. His release was contingent upon his acknowledgment of the Norman conquests in Calabria and Apulia.

6. Death

Pope Leo IX did not long survive his return to Rome after his captivity. He passed away on April 19, 1054, in Rome. His death occurred shortly after the dramatic events of the East-West Schism, though the excommunication bull delivered by Cardinal Humbert in Constantinople was legally invalid at the time of its delivery because Leo IX had already died. His body was interred in St. Peter's Basilica.

7. Legacy and Evaluation

Pope Leo IX's historical significance is profound, primarily due to his vigorous church reform efforts and his pivotal, albeit controversial, role in the East-West Schism. His pontificate laid crucial groundwork for the later Gregorian Reforms, demonstrating a strong commitment to combating corruption within the clergy.

His determined stance against simony and for clerical celibacy was a direct challenge to deeply entrenched practices, and his numerous synods across Europe effectively propagated these reformist ideals. He is widely praised for his steadfast leadership, his vision for church renewal, and his commitment to upholding the truth of the Gospel.

However, his legacy is also inextricably linked to the formal separation of the Eastern and Western Churches. While the schism was a culmination of centuries of theological, cultural, and political differences, Leo IX's assertive use of the (later proven forged) Donation of Constantine to claim papal supremacy, coupled with the aggressive actions of his legate Cardinal Humbert, undeniably escalated tensions and contributed directly to the definitive break. This highlights a complex aspect of his papacy, where his strong assertion of papal authority, while intended to unify and reform, ultimately led to a lasting division within Christendom.

7.1. Canonization and Commemoration

Pope Leo IX's dedication to reform and his perceived piety led to his recognition as a saint by the Catholic Church. He was canonized in 1087. His feast day is observed annually on April 19, the anniversary of his death. He remains a revered figure, remembered as a faithful shepherd, a courageous reformer, and a humble servant.